CAT Mock Test- 6 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test CAT Mock Test Series 2024 - CAT Mock Test- 6

Which of the following statements is the author LEAST likely to agree with?

I. Bad ideas are more likely to raise human interest and enthusiasm than good ideas.

II. People are cognizant of bad ideas but still rely on them to make sense of the world.

III. New ideas can lead to fresh perspectives on the functioning of the world.

IV. Most ideas have very little bearing on the functioning of the world.

I. Bad ideas are more likely to raise human interest and enthusiasm than good ideas.

II. People are cognizant of bad ideas but still rely on them to make sense of the world.

III. New ideas can lead to fresh perspectives on the functioning of the world.

IV. Most ideas have very little bearing on the functioning of the world.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Which of the following is NOT one of the effects associated with believing in conspiracy theories?

According to the passage, the perpetrators of silent treatment are compelled to justify their behavior because

"A myopic minority is more powerful than a distracted majority." Which of the following statements best captures the essence of this statement?

Which of the following statements can be inferred from the passage?

Which of the following statements is the author LEAST likely to agree with?

Which of the following statements is definitely TRUE according to the passage?

The author discusses the examples of the Leicestershire woman and the Black Plague to drive home the point that

Which of the following courses of action is the author LEAST likely to endorse?

Which of the following statements CANNOT be inferred from the passage?

I. Ubiquitous access to the internet and social networking websites has led to the repudiation of established facts.

II. Fear of losing their reputation and sponsors was one of the reasons that forced the earliest newsmen to filter out erroneous information scrupulously.

III. People trust journalists not because they report accurate information but because they debunk rumours.

IV. Misinformation campaigns could potentially amend the core values that define a democratic society.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

1. The dialogue was paralleled by the signing of the Japan-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation in March 2007, and joint military exercises between the United States, India, Japan, and Australia, titled Exercise Malabar.

2. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was initiated in August 2007 by then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan on "seas of freedom and prosperity", with the support of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of India, Vice President Dick Cheney of the US and Prime Minister John Howard of Australia.

3. The Chinese government responded to the Quad by issuing formal diplomatic protests to its members.

4. The diplomatic and military arrangement was widely viewed as a response to increased Chinese economic and military power.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

1. Last month, astronauts collected samples from across the interior of the ISS to build an unprecedented three-dimensional map of its microbiome.

2. We do not even know the full spectrum of spacefaring species living onboard the International Space Station (ISS), but new studies are designed to change that.

3. Yet we are still mostly in the dark about how these communities of microscopic hitchhikers react to microgravity.

4. Each astronaut voyaging off-world is accompanied by up to 100 trillion bacteria, viruses and other microorganisms, any number of which could jeopardize human health.

The five sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Each sentence is labelled with a number. Decide on the proper order for the sentences and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. Camelids are unusual in that their modern distribution is almost the reverse of their origin.

2. The original camelids of North America remained common until the quite recent geological past, but then disappeared, possibly as a result of hunting or habitat alterations by the earliest human settlers, and possibly as a result of changing environmental conditions after the last ice age, or a combination of these factors.

3. Camelids first appeared around 45 million years ago during the middle Eocene, in present-day North America.

4. Three species groups survived: the dromedary of northern Africa and southwest Asia; the Bactrian camel of central Asia; and the South American group, which has now diverged into a range of forms that are closely related, but usually classified as four species: llamas, alpacas, guanacos and vicuñas.

5. The family remained confined to the North American continent until only about two or three million years ago, when representatives arrived in Asia, and (as part of the Great American Interchange that followed the formation of the Isthmus of Panam1] South America.

There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, or 3) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: Such conditions often manifest subtly, with societal norms discouraging individuals from seeking timely help.

Paragraph: Mental health remains a taboo topic in many societies, even though it's crucial to overall well-being. The stress of modern life, relentless digital connectivity, and social isolation have led to a rise in conditions like depression and anxiety. ____ (1) ____ . To tackle this, awareness campaigns and access to professional help are being amplified. ____ (2) ____ . Yet, overcoming deeply ingrained prejudices about mental health issues proves to be a monumental challenge. ____ (3) ____ .

There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: In this pursuit, the idea of establishing a human settlement on Mars has captivated scientists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs alike.

Paragraph: The final frontier, space, has always been a source of human fascination. Astronomers and space agencies have long directed their resources toward the exploration of this vast unknown. ___ (1) ___ . The advancements in technology have enabled ambitious projects, such as probes sent to the farthest reaches of our solar system and telescopes peering into the depths of space and time. ___ (2) ___ . Despite these technological leaps, space travel presents significant challenges, including the physiological effects on astronauts and the sustainability of life in hostile environments. ___ (3) ___ . The prospect of interplanetary travel extends beyond scientific exploration, hinting at a potential future for humanity that could span multiple celestial bodies. ___ (4) ___ .

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

The influence of social media on public opinion is undeniable, serving as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it democratizes information, breaking monopolies that traditional media outlets had on public opinion. Conversely, it allows for the rampant spread of misinformation. During crises, this aspect becomes particularly dangerous, as seen in various health emergencies and political conflicts. The speed at which information (or misinformation) spreads can create unwarranted panic or prompt public responses based on falsehoods, showcasing the need for improved digital literacy and regulation.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

"Smart cities" integrate technology into urban planning, aiming to optimize efficiency for urban systems and improve residents' quality of life. However, the transformation into a smart city isn't without drawbacks. Critics argue that excessive reliance on technology can create more problems, like surveillance concerns, data security risks, and a widening digital divide, potentially leading to new forms of inequality. As cities continue to evolve, the challenge lies in leveraging technology for genuine societal benefits without infringing on individual rights or exacerbating social divides.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

The recent trend towards space tourism represents a significant milestone in human space exploration. However, it also brings forth ethical dilemmas. The exorbitant costs associated with these ventures highlight stark economic disparities, as only the wealthy can afford such experiences. Moreover, the environmental impact of increased space travel remains largely unaddressed, with potential consequences for Earth’s upper atmosphere and beyond. As space tourism continues to develop, a regulatory framework is needed to mitigate environmental damage and consider the broader implications of commercializing space.

Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

The rain flashed across the midnight window with a myriad feet. There was a groan in outer darkness, the voice of all nameless dreads. The nervous candle-flame shuddered by my bedside. The groaning rose to a shriek, and the little flame jumped in a panic, and nearly left its white column. Out of the corners of the room swarmed the released shadows. Black specters danced in ecstasy over my bed.............................................

They talk of the candle-power of an electric bulb. What do they mean? It cannot have the faintest glimmer of the real power of my candle. It would be as right to express, in the same inverted and foolish comparison, the worth of "those delicate sisters, the Pleiades." That pinch of star dust, the Pleiades, exquisitely remote in deepest night, in the profound where light all but fails, has not the power of a sulphur match; yet, still apprehensive to the mind though tremulous on the limit of vision, and sometimes even vanishing, it brings into distinction those distant and difficult hints—hidden far behind all our verified thoughts—which we rarely properly view. I should like to know of any great arc-lamp which could do that. So the star-like candle for me. No other light follows so intimately an author's most ghostly suggestion. We sit, the candle and I, in the midst of the shades we are conquering, and sometimes look up from the lucent page to contemplate the dark hosts of the enemy with a smile before they overwhelm us; as they will, of course. Like me, the candle is mortal; it will burn out.

As the bed-book itself should be a sort of night-light, to assist its illumination, coarse lamps are useless. They would douse the book. The light for such a book must accord with it. It must be, like the book, a limited, personal, mellow, and companionable glow; the solitary taper beside the only worshiper in a sanctuary. That is why nothing can compare with the intimacy of candle-light for a bed-book. It is a living heart, bright and warm in central night, burning for us alone, holding the gaunt and towering shadows at bay. There the monstrous specters stand in our midnight room, the advance guard of the darkness of the world, held off by our valiant little glim, but ready to flood instantly and founder us in original gloom.

The wind moans without; ancient evils are at large and wandering in torment. The rain shrieks across the window. For a moment, for just a moment, the sentinel candle is shaken, and burns blue with terror. The shadows leap out instantly. The little flame recovers, and merely looks at its foe the darkness, and back to its own place goes the old enemy of light and man. The candle for me, tiny, mortal, warm, and brave, a golden lily on a silver stem!

Q. Why is the author disappointed with the term 'the candle power of electirc bulb'?

Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

The rain flashed across the midnight window with a myriad feet. There was a groan in outer darkness, the voice of all nameless dreads. The nervous candle-flame shuddered by my bedside. The groaning rose to a shriek, and the little flame jumped in a panic, and nearly left its white column. Out of the corners of the room swarmed the released shadows. Black specters danced in ecstasy over my bed.............................................

They talk of the candle-power of an electric bulb. What do they mean? It cannot have the faintest glimmer of the real power of my candle. It would be as right to express, in the same inverted and foolish comparison, the worth of "those delicate sisters, the Pleiades." That pinch of star dust, the Pleiades, exquisitely remote in deepest night, in the profound where light all but fails, has not the power of a sulphur match; yet, still apprehensive to the mind though tremulous on the limit of vision, and sometimes even vanishing, it brings into distinction those distant and difficult hints—hidden far behind all our verified thoughts—which we rarely properly view. I should like to know of any great arc-lamp which could do that. So the star-like candle for me. No other light follows so intimately an author's most ghostly suggestion. We sit, the candle and I, in the midst of the shades we are conquering, and sometimes look up from the lucent page to contemplate the dark hosts of the enemy with a smile before they overwhelm us; as they will, of course. Like me, the candle is mortal; it will burn out.

As the bed-book itself should be a sort of night-light, to assist its illumination, coarse lamps are useless. They would douse the book. The light for such a book must accord with it. It must be, like the book, a limited, personal, mellow, and companionable glow; the solitary taper beside the only worshiper in a sanctuary. That is why nothing can compare with the intimacy of candle-light for a bed-book. It is a living heart, bright and warm in central night, burning for us alone, holding the gaunt and towering shadows at bay. There the monstrous specters stand in our midnight room, the advance guard of the darkness of the world, held off by our valiant little glim, but ready to flood instantly and founder us in original gloom.

The wind moans without; ancient evils are at large and wandering in torment. The rain shrieks across the window. For a moment, for just a moment, the sentinel candle is shaken, and burns blue with terror. The shadows leap out instantly. The little flame recovers, and merely looks at its foe the darkness, and back to its own place goes the old enemy of light and man. The candle for me, tiny, mortal, warm, and brave, a golden lily on a silver stem!

Q. From the information provided in the passage, we can infer that the Pleiades

Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

The rain flashed across the midnight window with a myriad feet. There was a groan in outer darkness, the voice of all nameless dreads. The nervous candle-flame shuddered by my bedside. The groaning rose to a shriek, and the little flame jumped in a panic, and nearly left its white column. Out of the corners of the room swarmed the released shadows. Black specters danced in ecstasy over my bed.............................................

They talk of the candle-power of an electric bulb. What do they mean? It cannot have the faintest glimmer of the real power of my candle. It would be as right to express, in the same inverted and foolish comparison, the worth of "those delicate sisters, the Pleiades." That pinch of star dust, the Pleiades, exquisitely remote in deepest night, in the profound where light all but fails, has not the power of a sulphur match; yet, still apprehensive to the mind though tremulous on the limit of vision, and sometimes even vanishing, it brings into distinction those distant and difficult hints—hidden far behind all our verified thoughts—which we rarely properly view. I should like to know of any great arc-lamp which could do that. So the star-like candle for me. No other light follows so intimately an author's most ghostly suggestion. We sit, the candle and I, in the midst of the shades we are conquering, and sometimes look up from the lucent page to contemplate the dark hosts of the enemy with a smile before they overwhelm us; as they will, of course. Like me, the candle is mortal; it will burn out.

As the bed-book itself should be a sort of night-light, to assist its illumination, coarse lamps are useless. They would douse the book. The light for such a book must accord with it. It must be, like the book, a limited, personal, mellow, and companionable glow; the solitary taper beside the only worshiper in a sanctuary. That is why nothing can compare with the intimacy of candle-light for a bed-book. It is a living heart, bright and warm in central night, burning for us alone, holding the gaunt and towering shadows at bay. There the monstrous specters stand in our midnight room, the advance guard of the darkness of the world, held off by our valiant little glim, but ready to flood instantly and founder us in original gloom.

The wind moans without; ancient evils are at large and wandering in torment. The rain shrieks across the window. For a moment, for just a moment, the sentinel candle is shaken, and burns blue with terror. The shadows leap out instantly. The little flame recovers, and merely looks at its foe the darkness, and back to its own place goes the old enemy of light and man. The candle for me, tiny, mortal, warm, and brave, a golden lily on a silver stem!

Q. Why does the author not consider coarse lamp to be a companion for a bed-book?

Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

The rain flashed across the midnight window with a myriad feet. There was a groan in outer darkness, the voice of all nameless dreads. The nervous candle-flame shuddered by my bedside. The groaning rose to a shriek, and the little flame jumped in a panic, and nearly left its white column. Out of the corners of the room swarmed the released shadows. Black specters danced in ecstasy over my bed.............................................

They talk of the candle-power of an electric bulb. What do they mean? It cannot have the faintest glimmer of the real power of my candle. It would be as right to express, in the same inverted and foolish comparison, the worth of "those delicate sisters, the Pleiades." That pinch of star dust, the Pleiades, exquisitely remote in deepest night, in the profound where light all but fails, has not the power of a sulphur match; yet, still apprehensive to the mind though tremulous on the limit of vision, and sometimes even vanishing, it brings into distinction those distant and difficult hints—hidden far behind all our verified thoughts—which we rarely properly view. I should like to know of any great arc-lamp which could do that. So the star-like candle for me. No other light follows so intimately an author's most ghostly suggestion. We sit, the candle and I, in the midst of the shades we are conquering, and sometimes look up from the lucent page to contemplate the dark hosts of the enemy with a smile before they overwhelm us; as they will, of course. Like me, the candle is mortal; it will burn out.

As the bed-book itself should be a sort of night-light, to assist its illumination, coarse lamps are useless. They would douse the book. The light for such a book must accord with it. It must be, like the book, a limited, personal, mellow, and companionable glow; the solitary taper beside the only worshiper in a sanctuary. That is why nothing can compare with the intimacy of candle-light for a bed-book. It is a living heart, bright and warm in central night, burning for us alone, holding the gaunt and towering shadows at bay. There the monstrous specters stand in our midnight room, the advance guard of the darkness of the world, held off by our valiant little glim, but ready to flood instantly and founder us in original gloom.

The wind moans without; ancient evils are at large and wandering in torment. The rain shrieks across the window. For a moment, for just a moment, the sentinel candle is shaken, and burns blue with terror. The shadows leap out instantly. The little flame recovers, and merely looks at its foe the darkness, and back to its own place goes the old enemy of light and man. The candle for me, tiny, mortal, warm, and brave, a golden lily on a silver stem!

Q. Which of the following can be said to be true about the shriek described in the first paragraph of the passage?

Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

The rain flashed across the midnight window with a myriad feet. There was a groan in outer darkness, the voice of all nameless dreads. The nervous candle-flame shuddered by my bedside. The groaning rose to a shriek, and the little flame jumped in a panic, and nearly left its white column. Out of the corners of the room swarmed the released shadows. Black specters danced in ecstasy over my bed.............................................

They talk of the candle-power of an electric bulb. What do they mean? It cannot have the faintest glimmer of the real power of my candle. It would be as right to express, in the same inverted and foolish comparison, the worth of "those delicate sisters, the Pleiades." That pinch of star dust, the Pleiades, exquisitely remote in deepest night, in the profound where light all but fails, has not the power of a sulphur match; yet, still apprehensive to the mind though tremulous on the limit of vision, and sometimes even vanishing, it brings into distinction those distant and difficult hints—hidden far behind all our verified thoughts—which we rarely properly view. I should like to know of any great arc-lamp which could do that. So the star-like candle for me. No other light follows so intimately an author's most ghostly suggestion. We sit, the candle and I, in the midst of the shades we are conquering, and sometimes look up from the lucent page to contemplate the dark hosts of the enemy with a smile before they overwhelm us; as they will, of course. Like me, the candle is mortal; it will burn out.

As the bed-book itself should be a sort of night-light, to assist its illumination, coarse lamps are useless. They would douse the book. The light for such a book must accord with it. It must be, like the book, a limited, personal, mellow, and companionable glow; the solitary taper beside the only worshiper in a sanctuary. That is why nothing can compare with the intimacy of candle-light for a bed-book. It is a living heart, bright and warm in central night, burning for us alone, holding the gaunt and towering shadows at bay. There the monstrous specters stand in our midnight room, the advance guard of the darkness of the world, held off by our valiant little glim, but ready to flood instantly and founder us in original gloom.

The wind moans without; ancient evils are at large and wandering in torment. The rain shrieks across the window. For a moment, for just a moment, the sentinel candle is shaken, and burns blue with terror. The shadows leap out instantly. The little flame recovers, and merely looks at its foe the darkness, and back to its own place goes the old enemy of light and man. The candle for me, tiny, mortal, warm, and brave, a golden lily on a silver stem!

Q: Why does the author describe the candle as "mortal"?

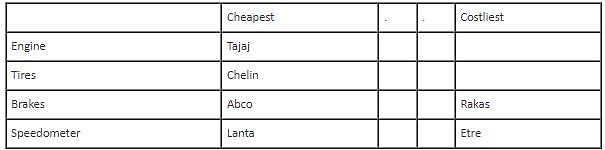

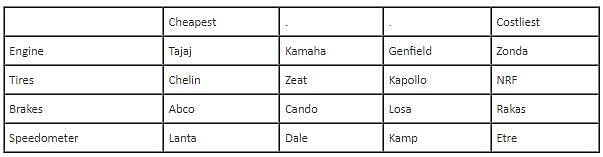

Directions: Answer the question on the basis of the information given below.

Akash, a mechanic, used to make and sell four types of custom-made bikes. He used four different brands of each of the four major components of bikes which were tires, engine, speedometer and brakes.

The different brands of tires were Kapollo, Zeat, Chelin and NRF. The different brands of engine were Kamaha, Zonda, Tajaj and Genfield. The different brands of speedometer were Lanta, Etre, Kamp and Dale. The different brands of brakes were Rakas, Cando, Abco and Losa. Out of the four models which Akash sold, one was the cheapest, in which he used the cheapest brand of all the four components, and the other was the costliest, in which he used the costliest brand of all the four components.

Further, the following information is known:

a) The Etre speedometer is the costliest among the four brands of speedometer.

b) Losa brakes can be fitted only with Kapollo tires.

c) Chelin tires can be fitted only with Abco brakes and Tajaj engine.

d) NRF tires cannot be fitted with Genfield engine, and Zeat tires can be fitted only with Kamaha engine.

e) The costliest brakes are neither of Cando nor of Losa brand.

f) Abco brakes and Lanta speedometer are used on the same bike.

g) Tajaj engines are the cheapest among the four engine brands.

h) Dale speedometer cannot be used with Chelin and Kapollo tires.

Q. Which brand's engine is the costliest?

|

16 videos|27 docs|58 tests

|

|

16 videos|27 docs|58 tests

|