Diagnostic Test: CAT - 2 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test 3 Months Preparation for CAT - Diagnostic Test: CAT - 2

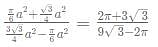

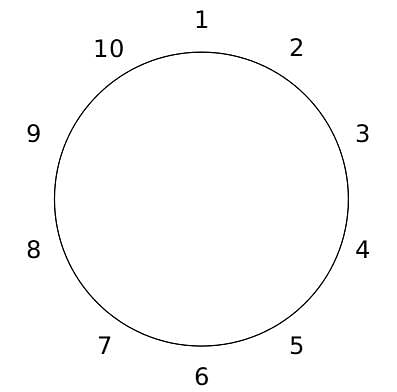

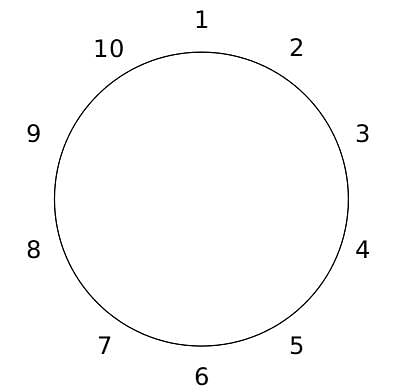

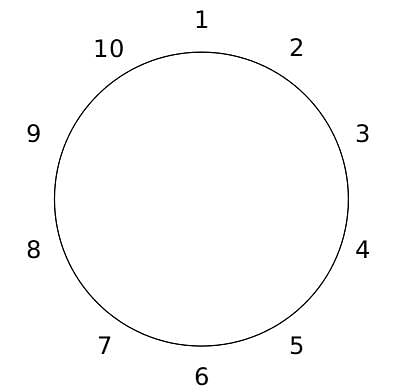

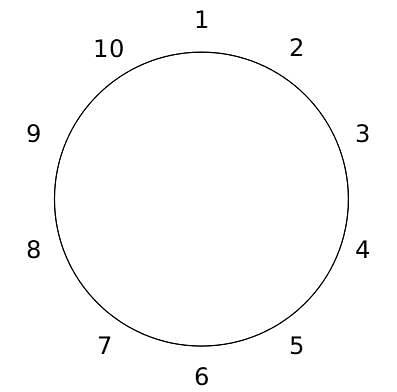

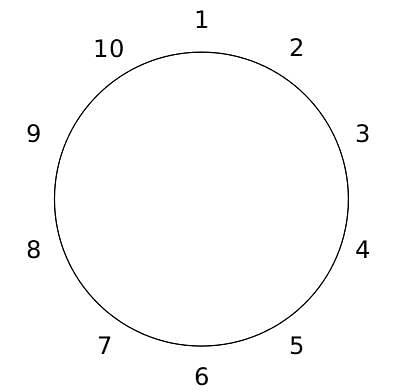

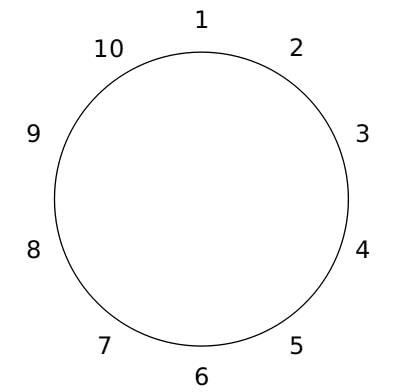

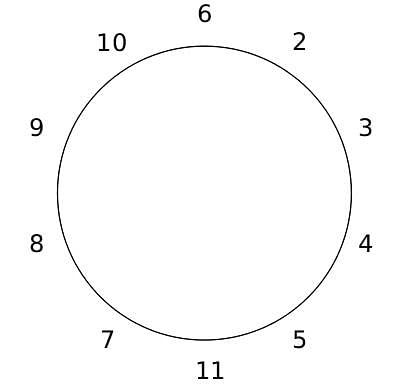

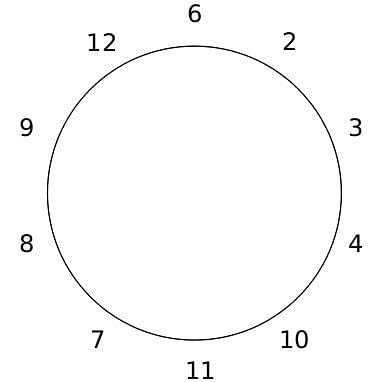

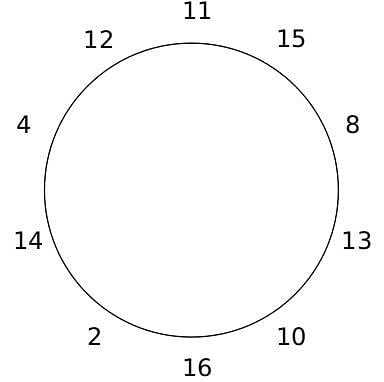

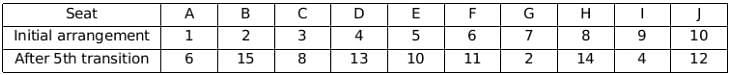

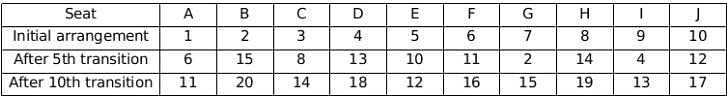

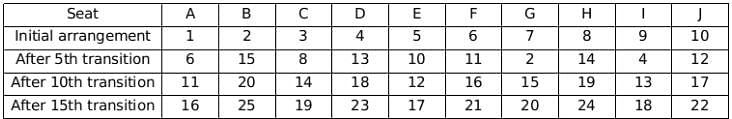

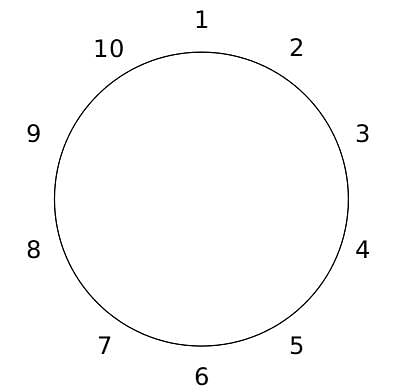

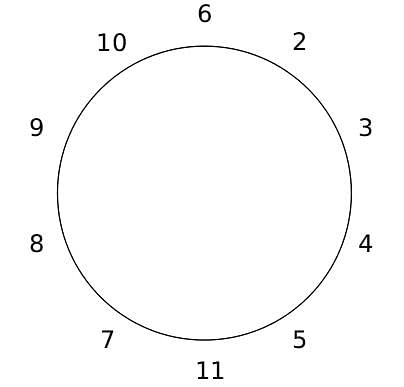

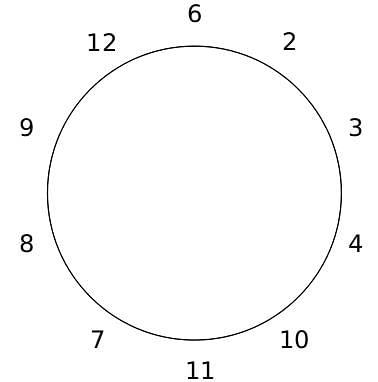

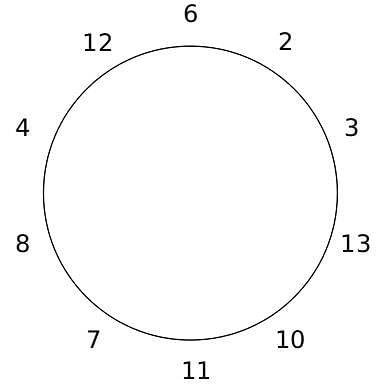

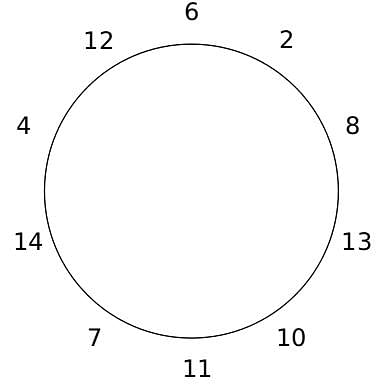

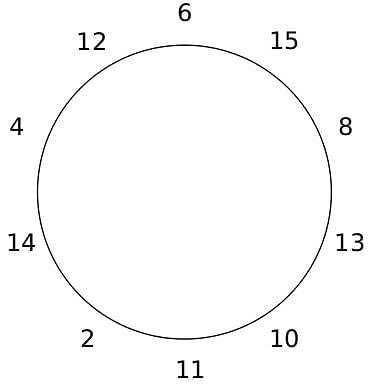

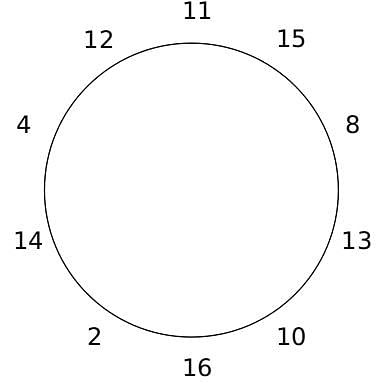

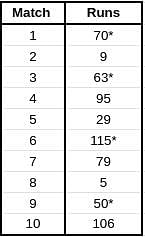

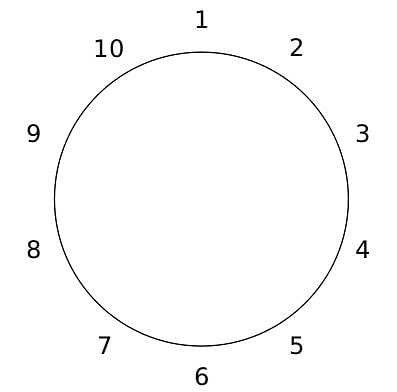

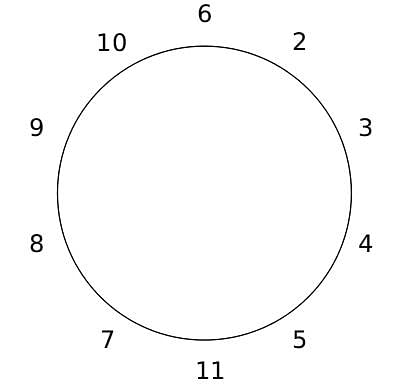

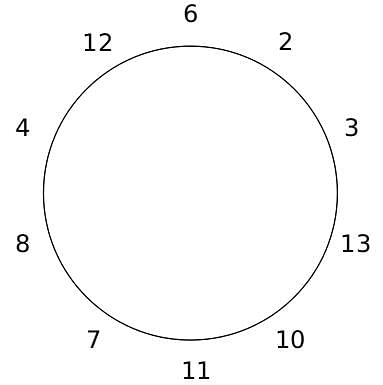

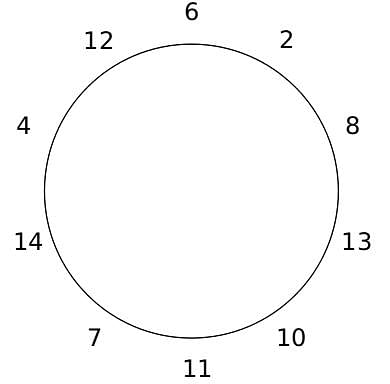

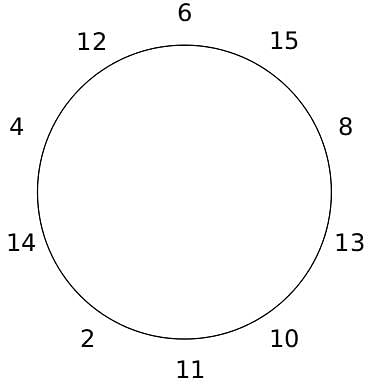

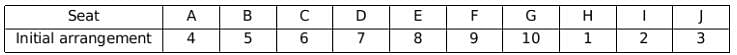

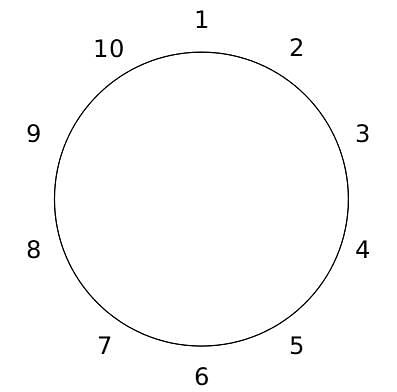

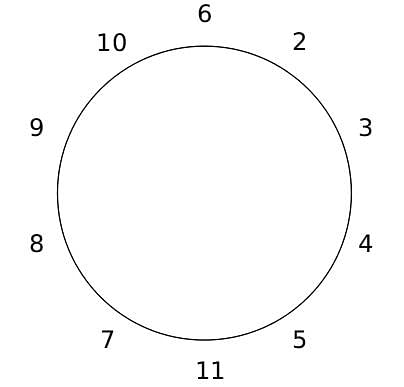

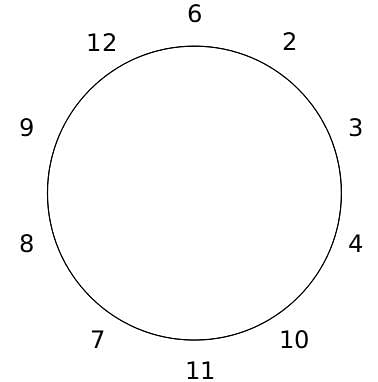

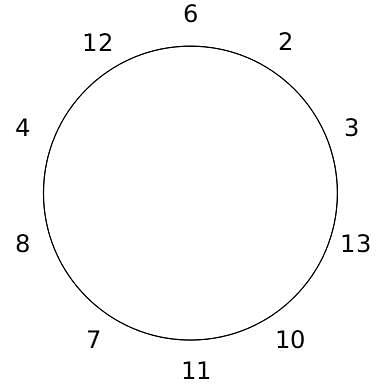

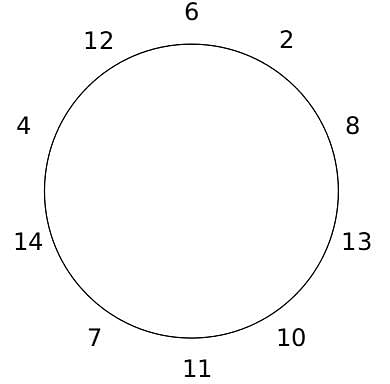

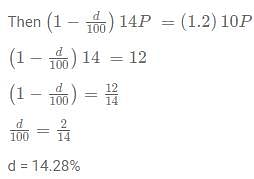

10 people are sitting around a circular table, each facing the table. They are numbered 1 to 10 and are sitting in the following manner.

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

Q. The person numbered 1 moves out of the table in the first transition. Which of the following persons remain on the table after the 15th transition?

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

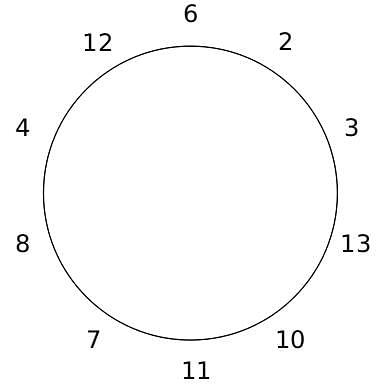

10 people are sitting around a circular table, each facing the table. They are numbered 1 to 10 and are sitting in the following manner.

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

Q. The person numbered 1 moves out of the table in the first transition. Which of the following represents all the people who remain seated after the 6th transition?

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

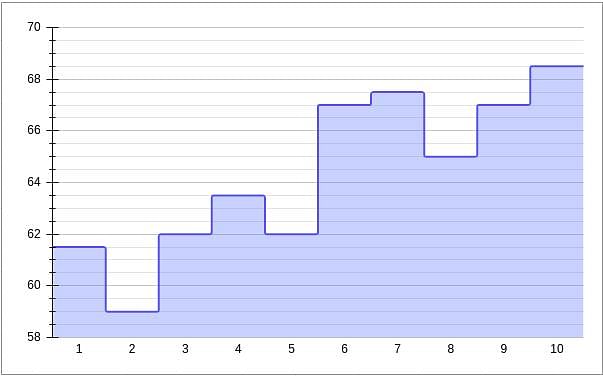

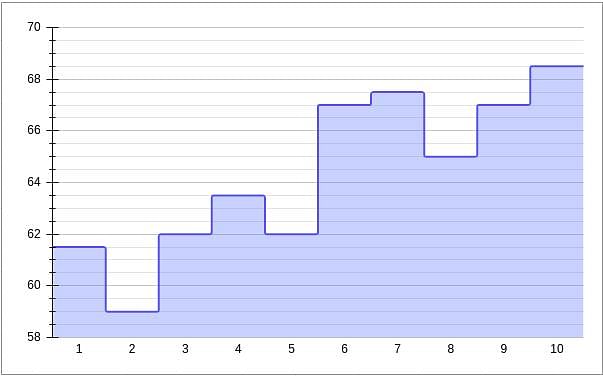

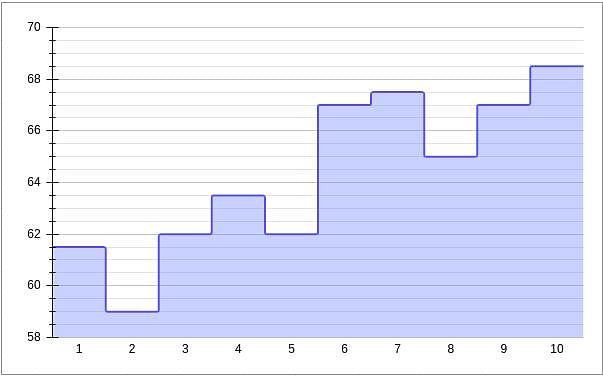

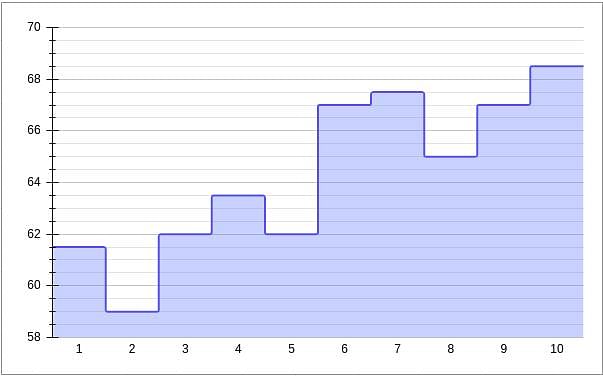

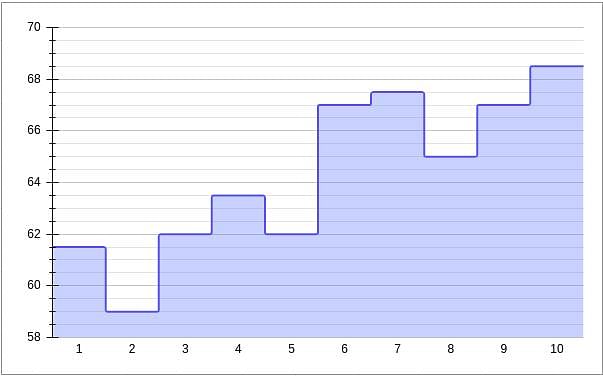

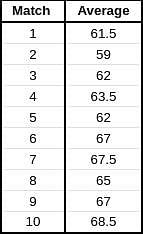

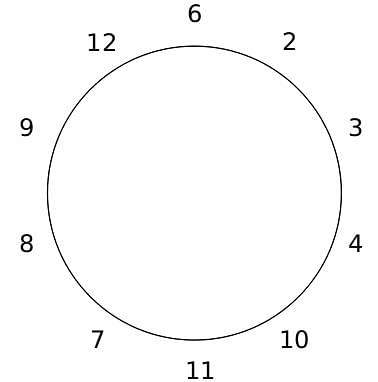

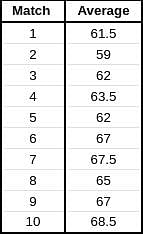

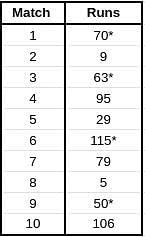

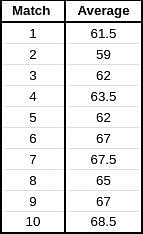

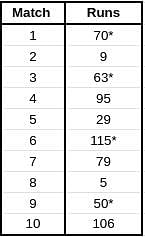

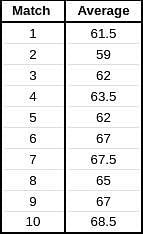

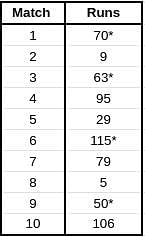

Given below is a chart showing the average of a batsman, which gets updated after every match that he plays in a tournament. Before the start of the tournament, wherein he played 10 matches, he averaged 58 in 20 innings. He got out in each one of them. The batsman played the tournament with an intent to remain not out in as many innings he can. In this tournament, the highest he could score was 115.

Consider, average of a batsman= Total runs scored in his career/Total time he was out

NOTE: Averages shown in the graph above are in multiples of 0.5

Q. What was the total career runs for the batsman just after the finish of the tournament?

Consider, average of a batsman= Total runs scored in his career/Total time he was out

NOTE: Averages shown in the graph above are in multiples of 0.5

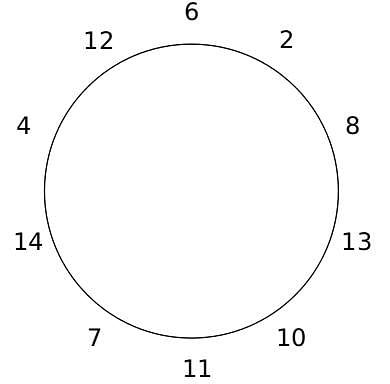

10 people are sitting around a circular table, each facing the table. They are numbered 1 to 10 and are sitting in the following manner.

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

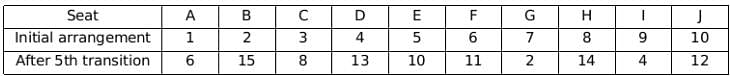

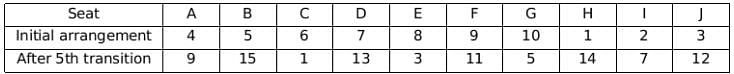

Q. The person numbered 4 moves out of the table in the first transition. Let Xn be the initial position of the person numbered n, and let Ym be the position of the person numbered m after the 5th transition. Which of the following pairs represent the same position?

10 people are sitting around a circular table, each facing the table. They are numbered 1 to 10 and are sitting in the following manner.

They sit in the same arrangement for some time, till there is a transition. In a transition, one person moves out of the table, and a different person moves in, although not in the same seat. It happens in the following manner. In the first transition, a particular person(say A) moves out of the table, the person sitting diametrically opposite to A(say B) replaces him(A), and a new person(say C) enters the position where B sat initially. Every new person coming into the table is numbered in a successive way. So, the first person joining the table when one person leaves will be numbered 11, the next person joining the table will be numbered 12 and so on. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of the person who joined last(say X), moves away. The person diametrically opposite to him(say Y) replaces him, and a new person(say Z) replaces Y. And this goes on. For example, suppose, in the first transition, 1 moves out of the table and 6 replaces him. A new person numbered 11 enters the position where 6 sat initially. In the second transition, the person to the immediate right of 11, that is 5, moves out of the table and 10 replaces him, and a new person 12 enters the position where 10 sat initially and it continues.

Based on the above information, answer the questions that follow.

Q. The person numbered 1 moves out of the table in the first transition. Which of the following persons move out of the table in the 4th transition?

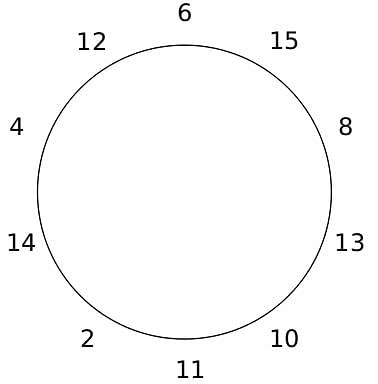

Given below is a chart showing the average of a batsman, which gets updated after every match that he plays in a tournament. Before the start of the tournament, wherein he played 10 matches, he averaged 58 in 20 innings. He got out in each one of them. The batsman played the tournament with an intent to remain not out in as many innings he can. In this tournament, the highest he could score was 115.

Consider, average of a batsman= Total runs scored in his career/Total time he was out

NOTE: Averages shown in the graph above are in multiples of 0.5

Q. What was the highest score of the batsman in the innings where he got out?

Given below is a chart showing the average of a batsman, which gets updated after every match that he plays in a tournament. Before the start of the tournament, wherein he played 10 matches, he averaged 58 in 20 innings. He got out in each one of them. The batsman played the tournament with an intent to remain not out in as many innings he can. In this tournament, the highest he could score was 115.

Consider, average of a batsman= Total runs scored in his career/Total time he was out

NOTE: Averages shown in the graph above are in multiples of 0.5

Q. What was the batsman's total career runs after the finish of the 6th match in the tournament?

Given below is a chart showing the average of a batsman, which gets updated after every match that he plays in a tournament. Before the start of the tournament, wherein he played 10 matches, he averaged 58 in 20 innings. He got out in each one of them. The batsman played the tournament with an intent to remain not out in as many innings he can. In this tournament, the highest he could score was 115.

Consider, average of a batsman= Total runs scored in his career/Total time he was out

NOTE: Averages shown in the graph above are in multiples of 0.5

Q. How many times was the batsman out in this tournament?

2 friends Virat and Sourav are playing a game that involves a dice. In each round, Virat rolls the dice twice, and then Sourav rolls the dice twice. If the sum of the numbers that Virat gets exceeds the sum of numbers that Sourav gets, Virat wins the round, else Sourav wins the round. In case the sum is the same, Sourav is given the advantage and he wins the round. The game ends when any one of them wins three consecutive rounds, and he is declared the winner. Based on the information given, answer the questions that follow.

Q. In a particular game, Sourav and Virat decide that either of them can start the first round, but whoever starts the first round has to start all subsequent rounds. Following is the sequence of numbers that come up starting from the first roll of dice in round 1. It is known that the game ends after the 12th throw of the dice (with the last roll of 2) as shown in the pattern.

3 6 5 4 2 5 A 1 B C 1 2

By varying the values of A, B and C, what is the total number of ways Sourav and Virat can throw the dice in the above pattern?

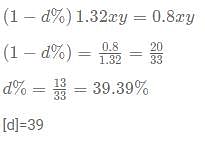

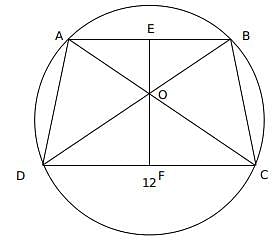

A cunning rice merchant uses a faulty weighing machine to cheat. While buying the rice from the whole seller he uses a faulty machine which shows the quantity 20% less than actually on the scale. While selling the rice, he uses another faulty scale which shows 10% extra weight than that on the scale. He marks up the price of rice by 20% on the rate he bought from the wholesaler. Sherlock found out about this scam and asked the rice seller to give approximately a d% discount on the current marked price so that the rice seller doesn't make a profit or a loss. What is the value of [d]?

[X] represents the largest integer less than or equal to X.

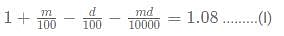

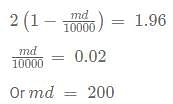

An absent-minded shopkeeper interchanged the markup of m% and discount d% of a product. So, instead of making a profit of 8%, he made a loss of 12% on the product. What is the value of d2 + m2?

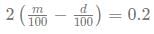

Let N be a natural number < 1500 exist such that when N divided by 7 has the same remainder when N3 is divided by 7. How many such values of N are there?

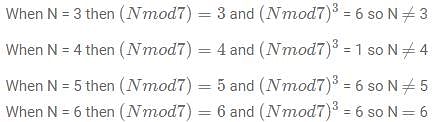

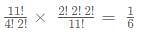

Among all the possible permutation of the word " VENKATESHAN" What is the probability that a word is chosen such that both the "A"s are before both the "E"s?

How many 4-digit numbers exist which is divisible by 3 or 8?

Siddhart is a pen-seller. He sells a pen such that the profit earned by selling 10 pens is equal to the cost price of 1 pen. The discount he gave on the marked price of the pen is 3 times the profit he earned by selling the pen. What approximate discount % should he offer the customer if he wishes to have a profit of 20%

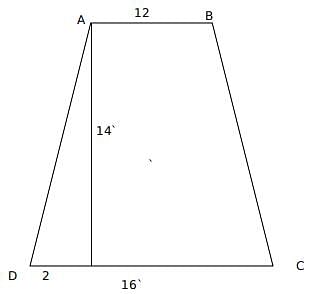

AB and CD are 2 parallel chords of a circle which has a radius of 10 units. Parallel chords are 14 units apart such that one of the chords has a length of 12 units. What is the length of non-parallel side of trapezium ABCD

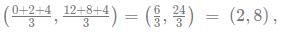

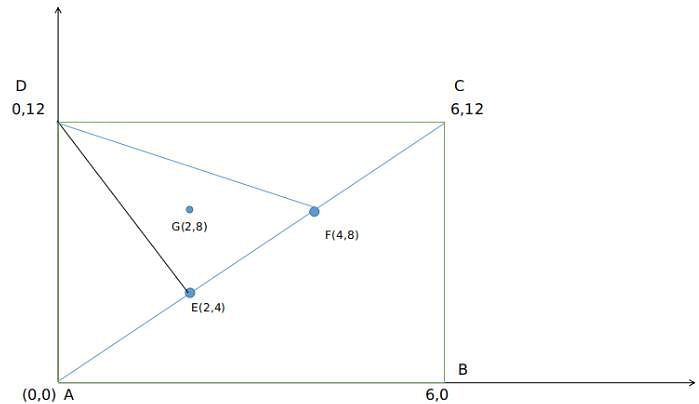

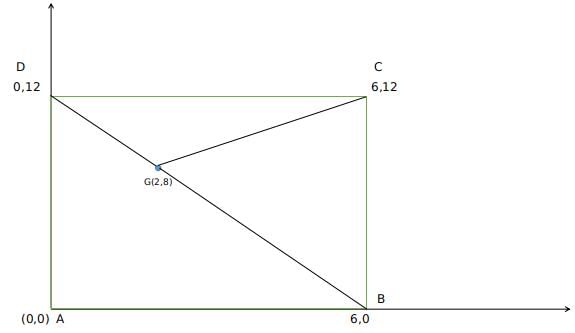

A rectangle ABCD exists such that AB = 6 units and BC = 12 units. E and F trisect the diagonal AC in 3 equal parts. G is centroid of the triangle formed by DEF. What is the area of DGBC?

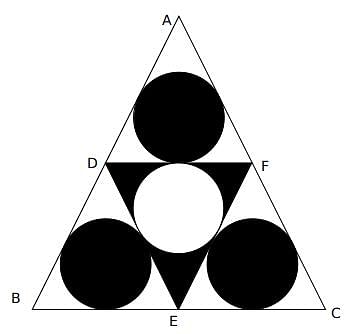

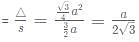

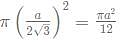

What is the ratio of the shaded region to non-shaded region in the following diagram

ABC is an equilateral triangle and D, E and F are the midpoint of the sides.

A number N is given by = 25 x 38 x 42 x 53 x 6 x 72

If a certain factor of N is not divisible by 9, the probability that the factor is an odd number is m/n where 'n' is a natural number less than 20. Find the value of m+n.

Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

With our climate-impacted world now highly prone to fires, extreme storms and sea-level rise, nuclear energy is touted as a possible replacement for the burning of fossil fuels for energy - the leading cause of climate change. Nuclear power can demonstrably reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Yet scientific evidence and recent catastrophes call into question whether nuclear power could function safely in our warming world. Wild weather, fires, rising sea levels, earthquakes and warming water temperatures all increase the risk of nuclear accidents, while the lack of safe, long-term storage for radioactive waste remains a persistent danger.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory property has had a long history of contaminated soil and groundwater. Indeed, a 2006 advisory panel compiled a report suggesting that workers at the lab, as well as residents living nearby, had unusually high exposure to radiation and industrial chemicals that are linked to an increased incidence of some cancers. Discovery of the pollution prompted California’s DTSC in 2010 to order cleanup of the site by its current owner - Boeing - with assistance from the US Department of Energy and NASA. But the required cleanup has been hampered by Boeing’s legal fight to perform a less rigorous cleaning.

Like the Santa Susana Field Lab, Chernobyl remains largely unremediated since its meltdown in 1986. With each passing year, dead plant material accumulates and temperatures rise, making it especially prone to fires in the era of climate change. Radiation releases from contaminated soils and forests can be carried thousands of kilometres away to human population centres, according to experts.

Kate Brown, a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), and Tim Mousseau, an evolutionary biologist at the University of South Carolina, also have grave concerns about forest fires. ‘Records show that there have been fires in the Chernobyl zone that raised the radiation levels by seven to 10 times since 1990,’ Brown says. Further north, melting glaciers contain ‘radioactive fallout from global nuclear testing and nuclear accidents at levels 10 times higher than elsewhere’. As ice melts, radioactive runoff flows into the ocean, is absorbed into the atmosphere, and falls as acid rain. ‘With fires and melting ice, we are basically paying back a debt of radioactive debris incurred during the frenzied production of nuclear byproducts during the 20th century,’ Brown concludes.

Flooding is another symptom of our warming world that could lead to nuclear disaster. Many nuclear plants are built on coastlines where seawater is easily used as a coolant. Sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, coastal storms and heat waves - all potentially catastrophic phenomena associated with climate change - are expected to get more frequent as the Earth continues to warm, threatening greater damage to coastal nuclear power plants. ‘Mere absence of greenhouse gas emissions is not sufficient to assess nuclear power as a mitigation for climate change,’ conclude Natalie Kopytko and John Perkins in their paper ‘Climate Change, Nuclear Power, and the Adaptation-Mitigation Dilemma’ (2011) in Energy Policy.

Proponents of nuclear power say that the reactors’ relative reliability and capacity make this a much clearer choice than other non-fossil-fuel sources of energy, such as wind and solar, which are sometimes brought offline by fluctuations in natural resource availability. Yet no one denies that older nuclear plants, with an aged infrastructure often surpassing expected lifetimes, are extremely inefficient and run a higher risk of disaster.

Q. Why does the author give the examples of the Santa Susana Lab and Chernobyl?

Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

With our climate-impacted world now highly prone to fires, extreme storms and sea-level rise, nuclear energy is touted as a possible replacement for the burning of fossil fuels for energy - the leading cause of climate change. Nuclear power can demonstrably reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Yet scientific evidence and recent catastrophes call into question whether nuclear power could function safely in our warming world. Wild weather, fires, rising sea levels, earthquakes and warming water temperatures all increase the risk of nuclear accidents, while the lack of safe, long-term storage for radioactive waste remains a persistent danger.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory property has had a long history of contaminated soil and groundwater. Indeed, a 2006 advisory panel compiled a report suggesting that workers at the lab, as well as residents living nearby, had unusually high exposure to radiation and industrial chemicals that are linked to an increased incidence of some cancers. Discovery of the pollution prompted California’s DTSC in 2010 to order cleanup of the site by its current owner - Boeing - with assistance from the US Department of Energy and NASA. But the required cleanup has been hampered by Boeing’s legal fight to perform a less rigorous cleaning.

Like the Santa Susana Field Lab, Chernobyl remains largely unremediated since its meltdown in 1986. With each passing year, dead plant material accumulates and temperatures rise, making it especially prone to fires in the era of climate change. Radiation releases from contaminated soils and forests can be carried thousands of kilometres away to human population centres, according to experts.

Kate Brown, a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), and Tim Mousseau, an evolutionary biologist at the University of South Carolina, also have grave concerns about forest fires. ‘Records show that there have been fires in the Chernobyl zone that raised the radiation levels by seven to 10 times since 1990,’ Brown says. Further north, melting glaciers contain ‘radioactive fallout from global nuclear testing and nuclear accidents at levels 10 times higher than elsewhere’. As ice melts, radioactive runoff flows into the ocean, is absorbed into the atmosphere, and falls as acid rain. ‘With fires and melting ice, we are basically paying back a debt of radioactive debris incurred during the frenzied production of nuclear byproducts during the 20th century,’ Brown concludes.

Flooding is another symptom of our warming world that could lead to nuclear disaster. Many nuclear plants are built on coastlines where seawater is easily used as a coolant. Sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, coastal storms and heat waves - all potentially catastrophic phenomena associated with climate change - are expected to get more frequent as the Earth continues to warm, threatening greater damage to coastal nuclear power plants. ‘Mere absence of greenhouse gas emissions is not sufficient to assess nuclear power as a mitigation for climate change,’ conclude Natalie Kopytko and John Perkins in their paper ‘Climate Change, Nuclear Power, and the Adaptation-Mitigation Dilemma’ (2011) in Energy Policy.

Proponents of nuclear power say that the reactors’ relative reliability and capacity make this a much clearer choice than other non-fossil-fuel sources of energy, such as wind and solar, which are sometimes brought offline by fluctuations in natural resource availability. Yet no one denies that older nuclear plants, with an aged infrastructure often surpassing expected lifetimes, are extremely inefficient and run a higher risk of disaster.

Q. What is the author's opinion on nuclear energy?

Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

With our climate-impacted world now highly prone to fires, extreme storms and sea-level rise, nuclear energy is touted as a possible replacement for the burning of fossil fuels for energy - the leading cause of climate change. Nuclear power can demonstrably reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Yet scientific evidence and recent catastrophes call into question whether nuclear power could function safely in our warming world. Wild weather, fires, rising sea levels, earthquakes and warming water temperatures all increase the risk of nuclear accidents, while the lack of safe, long-term storage for radioactive waste remains a persistent danger.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory property has had a long history of contaminated soil and groundwater. Indeed, a 2006 advisory panel compiled a report suggesting that workers at the lab, as well as residents living nearby, had unusually high exposure to radiation and industrial chemicals that are linked to an increased incidence of some cancers. Discovery of the pollution prompted California’s DTSC in 2010 to order cleanup of the site by its current owner - Boeing - with assistance from the US Department of Energy and NASA. But the required cleanup has been hampered by Boeing’s legal fight to perform a less rigorous cleaning.

Like the Santa Susana Field Lab, Chernobyl remains largely unremediated since its meltdown in 1986. With each passing year, dead plant material accumulates and temperatures rise, making it especially prone to fires in the era of climate change. Radiation releases from contaminated soils and forests can be carried thousands of kilometres away to human population centres, according to experts.

Kate Brown, a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), and Tim Mousseau, an evolutionary biologist at the University of South Carolina, also have grave concerns about forest fires. ‘Records show that there have been fires in the Chernobyl zone that raised the radiation levels by seven to 10 times since 1990,’ Brown says. Further north, melting glaciers contain ‘radioactive fallout from global nuclear testing and nuclear accidents at levels 10 times higher than elsewhere’. As ice melts, radioactive runoff flows into the ocean, is absorbed into the atmosphere, and falls as acid rain. ‘With fires and melting ice, we are basically paying back a debt of radioactive debris incurred during the frenzied production of nuclear byproducts during the 20th century,’ Brown concludes.

Flooding is another symptom of our warming world that could lead to nuclear disaster. Many nuclear plants are built on coastlines where seawater is easily used as a coolant. Sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, coastal storms and heat waves - all potentially catastrophic phenomena associated with climate change - are expected to get more frequent as the Earth continues to warm, threatening greater damage to coastal nuclear power plants. ‘Mere absence of greenhouse gas emissions is not sufficient to assess nuclear power as a mitigation for climate change,’ conclude Natalie Kopytko and John Perkins in their paper ‘Climate Change, Nuclear Power, and the Adaptation-Mitigation Dilemma’ (2011) in Energy Policy.

Proponents of nuclear power say that the reactors’ relative reliability and capacity make this a much clearer choice than other non-fossil-fuel sources of energy, such as wind and solar, which are sometimes brought offline by fluctuations in natural resource availability. Yet no one denies that older nuclear plants, with an aged infrastructure often surpassing expected lifetimes, are extremely inefficient and run a higher risk of disaster.

Q. What is the main point of the last paragraph?

Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

With our climate-impacted world now highly prone to fires, extreme storms and sea-level rise, nuclear energy is touted as a possible replacement for the burning of fossil fuels for energy - the leading cause of climate change. Nuclear power can demonstrably reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Yet scientific evidence and recent catastrophes call into question whether nuclear power could function safely in our warming world. Wild weather, fires, rising sea levels, earthquakes and warming water temperatures all increase the risk of nuclear accidents, while the lack of safe, long-term storage for radioactive waste remains a persistent danger.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory property has had a long history of contaminated soil and groundwater. Indeed, a 2006 advisory panel compiled a report suggesting that workers at the lab, as well as residents living nearby, had unusually high exposure to radiation and industrial chemicals that are linked to an increased incidence of some cancers. Discovery of the pollution prompted California’s DTSC in 2010 to order cleanup of the site by its current owner - Boeing - with assistance from the US Department of Energy and NASA. But the required cleanup has been hampered by Boeing’s legal fight to perform a less rigorous cleaning.

Like the Santa Susana Field Lab, Chernobyl remains largely unremediated since its meltdown in 1986. With each passing year, dead plant material accumulates and temperatures rise, making it especially prone to fires in the era of climate change. Radiation releases from contaminated soils and forests can be carried thousands of kilometres away to human population centres, according to experts.

Kate Brown, a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), and Tim Mousseau, an evolutionary biologist at the University of South Carolina, also have grave concerns about forest fires. ‘Records show that there have been fires in the Chernobyl zone that raised the radiation levels by seven to 10 times since 1990,’ Brown says. Further north, melting glaciers contain ‘radioactive fallout from global nuclear testing and nuclear accidents at levels 10 times higher than elsewhere’. As ice melts, radioactive runoff flows into the ocean, is absorbed into the atmosphere, and falls as acid rain. ‘With fires and melting ice, we are basically paying back a debt of radioactive debris incurred during the frenzied production of nuclear byproducts during the 20th century,’ Brown concludes.

Flooding is another symptom of our warming world that could lead to nuclear disaster. Many nuclear plants are built on coastlines where seawater is easily used as a coolant. Sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, coastal storms and heat waves - all potentially catastrophic phenomena associated with climate change - are expected to get more frequent as the Earth continues to warm, threatening greater damage to coastal nuclear power plants. ‘Mere absence of greenhouse gas emissions is not sufficient to assess nuclear power as a mitigation for climate change,’ conclude Natalie Kopytko and John Perkins in their paper ‘Climate Change, Nuclear Power, and the Adaptation-Mitigation Dilemma’ (2011) in Energy Policy.

Proponents of nuclear power say that the reactors’ relative reliability and capacity make this a much clearer choice than other non-fossil-fuel sources of energy, such as wind and solar, which are sometimes brought offline by fluctuations in natural resource availability. Yet no one denies that older nuclear plants, with an aged infrastructure often surpassing expected lifetimes, are extremely inefficient and run a higher risk of disaster.

Heidi Hutner & Erica Cirino

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.

Q. What was the conclusion based on the research by the MIT ?

Read the passage carefully and answer the following questions.

Country music has often been misrepresented to the world. Early on, it was deemed ‘hillbilly music’ by the very recording industry producing it, stereotypically linking it to a supposedly degenerate and backwards culture. We can see this image echoed on the front page of Variety in 1926, where the music critic Abel Green first defines the audience: ‘The “hill-billy” is a North Carolina or Tennessee and adjacent mountaineer type of illiterate white whose creed and allegiance are to the Bible … and the phonograph.’ Then the music got its lashing when Green described it as ‘the sing-song, nasal-twanging vocalising of a Vernon Dalhart or a Carson Robison … reciting the banal lyrics of a Prisoner’s Song or The Death of Floyd Collins …’

These kinds of negative projections of the people who have made country music, and have listened to it, linger even unto today. The stereotype is that they all harbour conservative political and social beliefs, setting them as sexist, racist, jingoistic and fundamentalist Christian by nature. But this image is a lie. For, right from the start, country music spoke up with a progressive voice.

One early example of this is from Blind Alfred Reed, who crafted How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? (1929). The song takes on the unjust practices of groups in power, such as in the lines: ‘preachers preach for gold and not for souls’ and ‘Officers kill without a cause.’ It presents the entirety of the working class as being victimised at the very dawn of the Great Depression. But Reed also wrote the religious song There’ll Be No Distinction There (1929), which illustrated an egalitarian afterlife in the lines: ‘We’ll all sit together in the same kind of pews, / The whites and the coloured folks, the gentiles and the Jews.’ But Reed was not alone in expressing sympathy for the working class or in calling out for a more equitable society: others from this early era - such as Uncle Dave Macon, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Henry Whitter - expressed similar sentiments, just as Johnny Cash, Steve Earle and John Rich have done in later decades.

Country music has also spoken out on women’s issues, such as in Loretta Lynn’s hit The Pill (1975). The song celebrates freedom from pregnancy, with the narrator noting how her husband has always been carefree and unfaithful while she was tied down with ‘a couple [babies] in my arms’ and another one on the way. Lynn’s message here is clear - she despises this kind of unequitable relationship, as she bluntly states in her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter (1976): ‘Well, shoot, I don’t believe in double standards, where men can get away with things that women can’t.’ In the country-music market, this song stands out as an unabashed and rather radical call for sexual liberation and biological control, challenging the man’s past sexual prerogative and presenting a situation where the woman may also enjoy a variety of sexual liaisons without the social/economic restrictions that come with pregnancy, childbirth and childcare. Lynn rejoices both in the song and in her own overall personal belief that the contraceptive pill will allow women greater control of their own lives.

Q. Which of the following adds the least depth to the author’s argument?

Read the passage carefully and answer the following questions.

Country music has often been misrepresented to the world. Early on, it was deemed ‘hillbilly music’ by the very recording industry producing it, stereotypically linking it to a supposedly degenerate and backwards culture. We can see this image echoed on the front page of Variety in 1926, where the music critic Abel Green first defines the audience: ‘The “hill-billy” is a North Carolina or Tennessee and adjacent mountaineer type of illiterate white whose creed and allegiance are to the Bible … and the phonograph.’ Then the music got its lashing when Green described it as ‘the sing-song, nasal-twanging vocalising of a Vernon Dalhart or a Carson Robison … reciting the banal lyrics of a Prisoner’s Song or The Death of Floyd Collins …’

These kinds of negative projections of the people who have made country music, and have listened to it, linger even unto today. The stereotype is that they all harbour conservative political and social beliefs, setting them as sexist, racist, jingoistic and fundamentalist Christian by nature. But this image is a lie. For, right from the start, country music spoke up with a progressive voice.

One early example of this is from Blind Alfred Reed, who crafted How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? (1929). The song takes on the unjust practices of groups in power, such as in the lines: ‘preachers preach for gold and not for souls’ and ‘Officers kill without a cause.’ It presents the entirety of the working class as being victimised at the very dawn of the Great Depression. But Reed also wrote the religious song There’ll Be No Distinction There (1929), which illustrated an egalitarian afterlife in the lines: ‘We’ll all sit together in the same kind of pews, / The whites and the coloured folks, the gentiles and the Jews.’ But Reed was not alone in expressing sympathy for the working class or in calling out for a more equitable society: others from this early era - such as Uncle Dave Macon, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Henry Whitter - expressed similar sentiments, just as Johnny Cash, Steve Earle and John Rich have done in later decades.

Country music has also spoken out on women’s issues, such as in Loretta Lynn’s hit The Pill (1975). The song celebrates freedom from pregnancy, with the narrator noting how her husband has always been carefree and unfaithful while she was tied down with ‘a couple [babies] in my arms’ and another one on the way. Lynn’s message here is clear - she despises this kind of unequitable relationship, as she bluntly states in her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter (1976): ‘Well, shoot, I don’t believe in double standards, where men can get away with things that women can’t.’ In the country-music market, this song stands out as an unabashed and rather radical call for sexual liberation and biological control, challenging the man’s past sexual prerogative and presenting a situation where the woman may also enjoy a variety of sexual liaisons without the social/economic restrictions that come with pregnancy, childbirth and childcare. Lynn rejoices both in the song and in her own overall personal belief that the contraceptive pill will allow women greater control of their own lives.

Q. The passage makes all the following claims EXCEPT:

- “Hill-billy” was considered a derogatory word.

- Country music was more progressive than it was perceived to be.

- The audience of country music was diverse.

Read the passage carefully and answer the following questions.

Country music has often been misrepresented to the world. Early on, it was deemed ‘hillbilly music’ by the very recording industry producing it, stereotypically linking it to a supposedly degenerate and backwards culture. We can see this image echoed on the front page of Variety in 1926, where the music critic Abel Green first defines the audience: ‘The “hill-billy” is a North Carolina or Tennessee and adjacent mountaineer type of illiterate white whose creed and allegiance are to the Bible … and the phonograph.’ Then the music got its lashing when Green described it as ‘the sing-song, nasal-twanging vocalising of a Vernon Dalhart or a Carson Robison … reciting the banal lyrics of a Prisoner’s Song or The Death of Floyd Collins …’

These kinds of negative projections of the people who have made country music, and have listened to it, linger even unto today. The stereotype is that they all harbour conservative political and social beliefs, setting them as sexist, racist, jingoistic and fundamentalist Christian by nature. But this image is a lie. For, right from the start, country music spoke up with a progressive voice.

One early example of this is from Blind Alfred Reed, who crafted How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? (1929). The song takes on the unjust practices of groups in power, such as in the lines: ‘preachers preach for gold and not for souls’ and ‘Officers kill without a cause.’ It presents the entirety of the working class as being victimised at the very dawn of the Great Depression. But Reed also wrote the religious song There’ll Be No Distinction There (1929), which illustrated an egalitarian afterlife in the lines: ‘We’ll all sit together in the same kind of pews, / The whites and the coloured folks, the gentiles and the Jews.’ But Reed was not alone in expressing sympathy for the working class or in calling out for a more equitable society: others from this early era - such as Uncle Dave Macon, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Henry Whitter - expressed similar sentiments, just as Johnny Cash, Steve Earle and John Rich have done in later decades.

Country music has also spoken out on women’s issues, such as in Loretta Lynn’s hit The Pill (1975). The song celebrates freedom from pregnancy, with the narrator noting how her husband has always been carefree and unfaithful while she was tied down with ‘a couple [babies] in my arms’ and another one on the way. Lynn’s message here is clear - she despises this kind of unequitable relationship, as she bluntly states in her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter (1976): ‘Well, shoot, I don’t believe in double standards, where men can get away with things that women can’t.’ In the country-music market, this song stands out as an unabashed and rather radical call for sexual liberation and biological control, challenging the man’s past sexual prerogative and presenting a situation where the woman may also enjoy a variety of sexual liaisons without the social/economic restrictions that come with pregnancy, childbirth and childcare. Lynn rejoices both in the song and in her own overall personal belief that the contraceptive pill will allow women greater control of their own lives.

Q. What is the author is trying to do by citing the example of Loretta Lynn?

Read the passage carefully and answer the following questions.

Country music has often been misrepresented to the world. Early on, it was deemed ‘hillbilly music’ by the very recording industry producing it, stereotypically linking it to a supposedly degenerate and backwards culture. We can see this image echoed on the front page of Variety in 1926, where the music critic Abel Green first defines the audience: ‘The “hill-billy” is a North Carolina or Tennessee and adjacent mountaineer type of illiterate white whose creed and allegiance are to the Bible … and the phonograph.’ Then the music got its lashing when Green described it as ‘the sing-song, nasal-twanging vocalising of a Vernon Dalhart or a Carson Robison … reciting the banal lyrics of a Prisoner’s Song or The Death of Floyd Collins …’

These kinds of negative projections of the people who have made country music, and have listened to it, linger even unto today. The stereotype is that they all harbour conservative political and social beliefs, setting them as sexist, racist, jingoistic and fundamentalist Christian by nature. But this image is a lie. For, right from the start, country music spoke up with a progressive voice.

One early example of this is from Blind Alfred Reed, who crafted How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? (1929). The song takes on the unjust practices of groups in power, such as in the lines: ‘preachers preach for gold and not for souls’ and ‘Officers kill without a cause.’ It presents the entirety of the working class as being victimised at the very dawn of the Great Depression. But Reed also wrote the religious song There’ll Be No Distinction There (1929), which illustrated an egalitarian afterlife in the lines: ‘We’ll all sit together in the same kind of pews, / The whites and the coloured folks, the gentiles and the Jews.’ But Reed was not alone in expressing sympathy for the working class or in calling out for a more equitable society: others from this early era - such as Uncle Dave Macon, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Henry Whitter - expressed similar sentiments, just as Johnny Cash, Steve Earle and John Rich have done in later decades.

Country music has also spoken out on women’s issues, such as in Loretta Lynn’s hit The Pill (1975). The song celebrates freedom from pregnancy, with the narrator noting how her husband has always been carefree and unfaithful while she was tied down with ‘a couple [babies] in my arms’ and another one on the way. Lynn’s message here is clear - she despises this kind of unequitable relationship, as she bluntly states in her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter (1976): ‘Well, shoot, I don’t believe in double standards, where men can get away with things that women can’t.’ In the country-music market, this song stands out as an unabashed and rather radical call for sexual liberation and biological control, challenging the man’s past sexual prerogative and presenting a situation where the woman may also enjoy a variety of sexual liaisons without the social/economic restrictions that come with pregnancy, childbirth and childcare. Lynn rejoices both in the song and in her own overall personal belief that the contraceptive pill will allow women greater control of their own lives.

Q. Which of the following statements can be inferred from the passage?

Four sentences are given below. These sentences, when rearranged in proper order, form a logical and meaningful paragraph. Rearrange the sentences and enter the correct order as the answer.

- Wherever the rhythm was most delicate, wherever the emotion was most ecstatic, her art was the most beautiful, and yet, although she sometimes spoke to a little tune, it was never singing, as we sing to-day, never anything but speech.

- I have always known that there was something I disliked about singing, and I naturally dislike print and paper, but now at last I understand why, for I have found something better.

- A friend, who was here a few minutes ago, has sat with a beautiful stringed instrument upon her knee, her fingers passing over the strings, and has spoken to me some verses from Shelley’s Skylark and Sir Ector’s lamentation over the dead Launcelot out of the Morte d’Arthur and some of my own poems.

- I have just heard a poem spoken with so delicate a sense of its rhythm, with so perfect a respect for its meaning, that if I were a wise man and could persuade a few people to learn the art I would never open a book of verses again.

Five sentences are given below. Four of which when arranged in a proper order, form a logical and meaningful paragraph. Identify the sentence that does not belong to the paragraph and enter its number as your answer.

- With the modern tendency toward specialization, the natural outgrowth of necessity, there is no inherent reason why the bones of a building should not be devised by one man and its fleshly clothing by another, so long as they understand one another, and are in ideal agreement, but there is in general all too little understanding, and a confusion of ideas and aims.

- Preoccupied as he is with the building's strength, safety, economy; solving new and staggeringly difficult problems with address and daring, he has scant sympathy with such inconsequent matters as the stylistic purity of a façade, or the profile of a moulding.

- To the designer, on the other hand, the engineer appears in the light of a subordinate to be used for the promotion of his own ends, or an evil to be endured as an interference with those ends.

- In the field of domestic architecture these dramatic contrasts are less evident, less sharply marked.

- To the average structural engineer the architectural designer is a mere milliner in stone, informed in those prevailing architectural fashions of which he himself knows little and cares less.

Five sentences are given below labelled as 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Of these, four sentences, when arranged properly, make a meaningful and coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out.

- Even where the advancer of the art was also a psychologist, the pedagogics and the psychology ran side by side, and the former was not derived in any sense from the latter.

- To know psychology, therefore, is absolutely no guarantee that we shall be good teachers.

- The art of teaching grew up in the schoolroom, out of inventiveness and sympathetic concrete observation.

- That ingenuity in meeting and pursuing the pupil, that tact for the concrete situation, though they are the alpha and omega of the teacher's art, are things to which psychology cannot help us in the least.

- The two were congruent, but neither was subordinate.

|

284 videos|394 docs|249 tests

|

|

284 videos|394 docs|249 tests

|

- Shaded area

- Shaded area