IIFT Mock Test - 1 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 1 (New Pattern)

Read the following sets of four sentences and arrange them in the most logical sequence to form a meaningful and coherent paragraph.

I. Why would anyone spend thousands of dollars on a Prada handbag, an Armani suit, or a Rolex watch?

II. What drives people to possess so much more than they need?

III. Certain consumer behaviors seem irrational, wasteful, even evil.

IV. If you really need to know the time, buy a cheap Timex or just look at your phone and send the money you have saved to Oxfam.

Which of the following words is spelled correctly?

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Fill in the blanks with the most appropriate option.

The ___________ flora of the royal garden enchanted all the visitors

Choose the option that is grammatically correct, effective and reduces ambiguity and redundancy.

The rate of patents being awarded is continuously increasing as technology advances forward, and it is a welcome news.

Select the option which expresses a relationship similar to the one expressed in the capitalized pair.

INDIGENT : OPULENT

The first and last part of a sentence are marked 1 and 6. The rest of the sentence is split into 5 parts and marked i, ii, iii, iv and v. These five parts are not given in their proper order. From the options given, please choose the most appropriate order to form a coherent, logical and grammatically correct sentence.

1. In addition to

i. DT Max argues is the novel's true subject;

ii. allow Lowry to constantly drop references to what,

iii. all those sub-clauses,

iv. and piled-up details,

v. rendering consciousness and longing,

6. the Second World War.

Select the option which is grammatically correct.

Fill in the blanks with the word or phrase that completes the idiom correctly in the given sentences.

"You have to stop stealing __________! Every time I tell that I'm going to do something, you do it first and you always get the recognition!".

Fill in the blanks:-

He stopped his studies ___________ his father had passed away.

Read the following sets of four sentences and arrange them in the most logical sequence to form a meaningful and coherent paragraph.

I. Moreover, I would argue that if we don't first imagine a possible future, we can never implement the practical steps that might make it a reality.

II. As a result, if we want to change the future for the better we must be prepared to encounter numerous obstacles.

III. We are, of course, constrained in our actions by the cumulative historical impact of ignorance and greed and the struggle for power, often accentuated by governments or churches whose interests may lie in permeating myths that build support for the status quo and squelch calls for change.

IV. But I am a theoretical physicist trained to worry about possibilities, not practicalities.

Which of the following options has both words spelled correctly?

Fill in the blanks with the most appropriate option.

The sight of a clergyman on her doorstep transformed her in an instant from a _______into a quietly spoken model of respectability.

Choose the option that is grammatically correct, effective and reduces ambiguity and redundancy.

The government decided that the immigrants should not be given all the refugee benefits because it believed that to do it encourages others to enter the country illegally.

Select the option which expresses a relationship similar to the one expressed in the capitalized pair.

IGNORAMUS : SIMPLETON

The first and last part of a sentence are marked 1 and 6. The rest of the sentence is split into 5 parts and marked i, ii, iii, iv and v. These five parts are not given in their proper order. From the options given, please choose the most appropriate order to form a coherent, logical and grammatically correct sentence.

1. It is up to us

i. To determine,

ii. Intelligence,

iii. The nature of the way,

iv. In which we carry out our lives,

v. Using a combination of reason,

6. and compassion.

Select the option which is grammatically correct.

Fill in the blanks with the word or phrase that completes the idiom correctly in the given sentences.

Having walked twenty miles, he is quite done _______.

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight time-delayed miniature camera could be attached. Neubronner's German patent application was initially rejected, but was granted in December 1908 after he produced authenticated photographs taken by his pigeons. He publicized the technique at the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, and sold some images as postcards at the Frankfurt International Aviation Exhibition and at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Initially, the military potential of pigeon photography for aerial reconnaissance appeared attractive. Battlefield tests in the First World War provided encouraging results, but the ancillary technology of mobile dovecotes for messenger pigeons had the greatest impact. Owing to the rapid perfection of aviation during the war, military interest in pigeon photography faded and Neubronner abandoned his experiments. The idea was briefly resurrected in the 1930s by a Swiss clockmaker, and reportedly also by the German and French militaries. Although war pigeons were deployed extensively during the Second World War, it is unclear to what extent, if any, birds were involved in aerial reconnaissance. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) later developed a battery-powered camera designed for espionage pigeon photography; details of its use remain classified.

The construction of sufficiently small and light cameras with a timer mechanism, and the training and handling of the birds to carry the necessary loads, presented major challenges, as did the limited control over the pigeons' position, orientation and speed when the photographs were being taken. In 2004, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) used miniature television cameras attached to falcons and goshawks to obtain live footage, and today some researchers, enthusiasts and artists similarly deploy crittercams with various species of animals.

The first aerial photographs were taken in 1858 by the balloonist Nadar; in 1860 James Wallace Black took the oldest surviving aerial photographs, also from a balloon. As photographic techniques made further progress, at the end of the 19th century some pioneers placed cameras in unmanned flying objects. In the 1880s, Arthur Batut experimented with kite aerial photography. Many others followed him, and high-quality photographs of Boston taken with this method by William Abner Eddy in 1896 became famous. AmedeeDenisse equipped a rocket with a camera and a parachute in 1888, and Alfred Nobel also used rocket photography in 1897.

Homing pigeons were used extensively in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both for civil pigeon post and as war pigeons. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the famous pigeon post of Paris carried up to 50,000 microfilmed telegrams per pigeon flight from Tours into the besieged capital. Altogether 150,000 individual private telegrams and state dispatches were delivered. In an 1889 experiment of the Imperial Russian Technical Society at Saint Petersburg, the chief of the Russian balloon corps took aerial photographs from a balloon and sent the developed collodion film negatives to the ground by pigeon post.

In 1903 Julius Neubronner, an apothecary in the German town of Kronberg near Frankfurt, resumed a practice begun by his father half a century earlier and received prescriptions from a sanatorium in nearby Falkenstein via pigeon post. (The pigeon post was discontinued after three years when the sanatorium was closed.) He delivered urgent medications up to 75 grams (2.6 oz) by the same method, and positioned some of his pigeons with his wholesaler in Frankfurt to profit from faster deliveries himself. When one of his pigeons lost its orientation in fog and mysteriously arrived, well-fed, four weeks late, Neubronner was inspired with the playful idea of equipping his pigeons with automatic cameras to trace their paths. This thought led him to merge his two hobbies into a new "double sport" combining carrier pigeon fancying with amateur photography. (Neubronner later learned that his pigeon had been in the custody of a restaurant chef in Wiesbaden.)

After successfully testing a Ticka watch camera on a train and whilst riding a sled, Neubronner began the development of a light miniature camera that could be fitted to a pigeon's breast by means of a harness and an aluminum cuirass. Using wooden camera models which weighed 30 to 75 grams (1.1 to 2.6 oz), the pigeons were carefully trained for their load. To take an aerial photograph, Neubronner carried a pigeon to a location up to about 100 kilometres (60 mi) from its home, where it was equipped with a camera and released. The bird, keen to be relieved of its burden, would typically fly home on a direct route, at a height of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft).[10] A pneumatic system in the camera controlled the time delay before a photograph was taken. To accommodate the burdened pigeon, the dovecote had a spacious, elastic landing board and a large entry hole.

According to Neubronner, there were a dozen different models of his camera. In 1907 he had sufficient success to apply for a patent. Initially his invention "Method of and Means for Taking Photographs of Landscapes from Above" was rejected by the German patent office as impossible, but after presentation of authenticated photographs the patent was granted in December 1908. (The rejection was based on a misconception about the carrying capacity of domestic pigeons). The technology became widely known through Neubronner's participation in the 1909 International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden and the 1909 International Aviation Exhibition in Frankfurt. Spectators in Dresden could watch the arrival of the pigeons, and the aerial photographs they brought back were turned into postcards. Neubronner's photographs won prizes in Dresden as well as at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Q. Identify the correct statement:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight time-delayed miniature camera could be attached. Neubronner's German patent application was initially rejected, but was granted in December 1908 after he produced authenticated photographs taken by his pigeons. He publicized the technique at the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, and sold some images as postcards at the Frankfurt International Aviation Exhibition and at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Initially, the military potential of pigeon photography for aerial reconnaissance appeared attractive. Battlefield tests in the First World War provided encouraging results, but the ancillary technology of mobile dovecotes for messenger pigeons had the greatest impact. Owing to the rapid perfection of aviation during the war, military interest in pigeon photography faded and Neubronner abandoned his experiments. The idea was briefly resurrected in the 1930s by a Swiss clockmaker, and reportedly also by the German and French militaries. Although war pigeons were deployed extensively during the Second World War, it is unclear to what extent, if any, birds were involved in aerial reconnaissance. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) later developed a battery-powered camera designed for espionage pigeon photography; details of its use remain classified.

The construction of sufficiently small and light cameras with a timer mechanism, and the training and handling of the birds to carry the necessary loads, presented major challenges, as did the limited control over the pigeons' position, orientation and speed when the photographs were being taken. In 2004, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) used miniature television cameras attached to falcons and goshawks to obtain live footage, and today some researchers, enthusiasts and artists similarly deploy crittercams with various species of animals.

The first aerial photographs were taken in 1858 by the balloonist Nadar; in 1860 James Wallace Black took the oldest surviving aerial photographs, also from a balloon. As photographic techniques made further progress, at the end of the 19th century some pioneers placed cameras in unmanned flying objects. In the 1880s, Arthur Batut experimented with kite aerial photography. Many others followed him, and high-quality photographs of Boston taken with this method by William Abner Eddy in 1896 became famous. AmedeeDenisse equipped a rocket with a camera and a parachute in 1888, and Alfred Nobel also used rocket photography in 1897.

Homing pigeons were used extensively in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both for civil pigeon post and as war pigeons. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the famous pigeon post of Paris carried up to 50,000 microfilmed telegrams per pigeon flight from Tours into the besieged capital. Altogether 150,000 individual private telegrams and state dispatches were delivered. In an 1889 experiment of the Imperial Russian Technical Society at Saint Petersburg, the chief of the Russian balloon corps took aerial photographs from a balloon and sent the developed collodion film negatives to the ground by pigeon post.

In 1903 Julius Neubronner, an apothecary in the German town of Kronberg near Frankfurt, resumed a practice begun by his father half a century earlier and received prescriptions from a sanatorium in nearby Falkenstein via pigeon post. (The pigeon post was discontinued after three years when the sanatorium was closed.) He delivered urgent medications up to 75 grams (2.6 oz) by the same method, and positioned some of his pigeons with his wholesaler in Frankfurt to profit from faster deliveries himself. When one of his pigeons lost its orientation in fog and mysteriously arrived, well-fed, four weeks late, Neubronner was inspired with the playful idea of equipping his pigeons with automatic cameras to trace their paths. This thought led him to merge his two hobbies into a new "double sport" combining carrier pigeon fancying with amateur photography. (Neubronner later learned that his pigeon had been in the custody of a restaurant chef in Wiesbaden.)

After successfully testing a Ticka watch camera on a train and whilst riding a sled, Neubronner began the development of a light miniature camera that could be fitted to a pigeon's breast by means of a harness and an aluminum cuirass. Using wooden camera models which weighed 30 to 75 grams (1.1 to 2.6 oz), the pigeons were carefully trained for their load. To take an aerial photograph, Neubronner carried a pigeon to a location up to about 100 kilometres (60 mi) from its home, where it was equipped with a camera and released. The bird, keen to be relieved of its burden, would typically fly home on a direct route, at a height of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft).[10] A pneumatic system in the camera controlled the time delay before a photograph was taken. To accommodate the burdened pigeon, the dovecote had a spacious, elastic landing board and a large entry hole.

According to Neubronner, there were a dozen different models of his camera. In 1907 he had sufficient success to apply for a patent. Initially his invention "Method of and Means for Taking Photographs of Landscapes from Above" was rejected by the German patent office as impossible, but after presentation of authenticated photographs the patent was granted in December 1908. (The rejection was based on a misconception about the carrying capacity of domestic pigeons). The technology became widely known through Neubronner's participation in the 1909 International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden and the 1909 International Aviation Exhibition in Frankfurt. Spectators in Dresden could watch the arrival of the pigeons, and the aerial photographs they brought back were turned into postcards. Neubronner's photographs won prizes in Dresden as well as at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

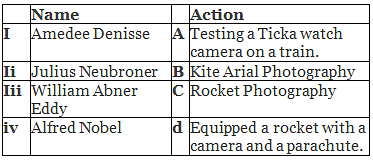

Q. Match the following:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight time-delayed miniature camera could be attached. Neubronner's German patent application was initially rejected, but was granted in December 1908 after he produced authenticated photographs taken by his pigeons. He publicized the technique at the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, and sold some images as postcards at the Frankfurt International Aviation Exhibition and at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Initially, the military potential of pigeon photography for aerial reconnaissance appeared attractive. Battlefield tests in the First World War provided encouraging results, but the ancillary technology of mobile dovecotes for messenger pigeons had the greatest impact. Owing to the rapid perfection of aviation during the war, military interest in pigeon photography faded and Neubronner abandoned his experiments. The idea was briefly resurrected in the 1930s by a Swiss clockmaker, and reportedly also by the German and French militaries. Although war pigeons were deployed extensively during the Second World War, it is unclear to what extent, if any, birds were involved in aerial reconnaissance. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) later developed a battery-powered camera designed for espionage pigeon photography; details of its use remain classified.

The construction of sufficiently small and light cameras with a timer mechanism, and the training and handling of the birds to carry the necessary loads, presented major challenges, as did the limited control over the pigeons' position, orientation and speed when the photographs were being taken. In 2004, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) used miniature television cameras attached to falcons and goshawks to obtain live footage, and today some researchers, enthusiasts and artists similarly deploy crittercams with various species of animals.

The first aerial photographs were taken in 1858 by the balloonist Nadar; in 1860 James Wallace Black took the oldest surviving aerial photographs, also from a balloon. As photographic techniques made further progress, at the end of the 19th century some pioneers placed cameras in unmanned flying objects. In the 1880s, Arthur Batut experimented with kite aerial photography. Many others followed him, and high-quality photographs of Boston taken with this method by William Abner Eddy in 1896 became famous. AmedeeDenisse equipped a rocket with a camera and a parachute in 1888, and Alfred Nobel also used rocket photography in 1897.

Homing pigeons were used extensively in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both for civil pigeon post and as war pigeons. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the famous pigeon post of Paris carried up to 50,000 microfilmed telegrams per pigeon flight from Tours into the besieged capital. Altogether 150,000 individual private telegrams and state dispatches were delivered. In an 1889 experiment of the Imperial Russian Technical Society at Saint Petersburg, the chief of the Russian balloon corps took aerial photographs from a balloon and sent the developed collodion film negatives to the ground by pigeon post.

In 1903 Julius Neubronner, an apothecary in the German town of Kronberg near Frankfurt, resumed a practice begun by his father half a century earlier and received prescriptions from a sanatorium in nearby Falkenstein via pigeon post. (The pigeon post was discontinued after three years when the sanatorium was closed.) He delivered urgent medications up to 75 grams (2.6 oz) by the same method, and positioned some of his pigeons with his wholesaler in Frankfurt to profit from faster deliveries himself. When one of his pigeons lost its orientation in fog and mysteriously arrived, well-fed, four weeks late, Neubronner was inspired with the playful idea of equipping his pigeons with automatic cameras to trace their paths. This thought led him to merge his two hobbies into a new "double sport" combining carrier pigeon fancying with amateur photography. (Neubronner later learned that his pigeon had been in the custody of a restaurant chef in Wiesbaden.)

After successfully testing a Ticka watch camera on a train and whilst riding a sled, Neubronner began the development of a light miniature camera that could be fitted to a pigeon's breast by means of a harness and an aluminum cuirass. Using wooden camera models which weighed 30 to 75 grams (1.1 to 2.6 oz), the pigeons were carefully trained for their load. To take an aerial photograph, Neubronner carried a pigeon to a location up to about 100 kilometres (60 mi) from its home, where it was equipped with a camera and released. The bird, keen to be relieved of its burden, would typically fly home on a direct route, at a height of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft).[10] A pneumatic system in the camera controlled the time delay before a photograph was taken. To accommodate the burdened pigeon, the dovecote had a spacious, elastic landing board and a large entry hole.

According to Neubronner, there were a dozen different models of his camera. In 1907 he had sufficient success to apply for a patent. Initially his invention "Method of and Means for Taking Photographs of Landscapes from Above" was rejected by the German patent office as impossible, but after presentation of authenticated photographs the patent was granted in December 1908. (The rejection was based on a misconception about the carrying capacity of domestic pigeons). The technology became widely known through Neubronner's participation in the 1909 International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden and the 1909 International Aviation Exhibition in Frankfurt. Spectators in Dresden could watch the arrival of the pigeons, and the aerial photographs they brought back were turned into postcards. Neubronner's photographs won prizes in Dresden as well as at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Q. Identify the incorrect statement:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

In March 2008, the kingdom of Bhutan, an often invisible Shangri-La tucked away strategically in the Himalayas between India and China, became the world's youngest democracy. An absolute monarchy gave way to a constitutional monarchy, a new Constitution mandating a parliamentary democracy was adopted, and, for the first time, the people of Bhutan voted, on the basis of universal suffrage, to elect a new Parliament consisting of a National Council or Upper House with 25 members, and a National Assembly or Lower House with 47 members. Jigme Thinley became the country's first democratically elected Prime Minister. In the second elections in 2013, his Peace and Prosperity Party was defeated by the People's Democratic Party. Its leader, TsheringTobgay, a young Harvard educated man in his mid-forties, is today the Prime Minister of Bhutan.

When I went as Ambassador of India to Bhutan in 2009, many foreign observers believed that the adoption of parliamentary democracy was more a cosmetic exercise which essentially left untouched the unfettered sway of the monarchy. It is true, of course, that the monarchy continues to enjoy a very high degree of reverence and popularity. But it would be wrong to believe that democracy in this once absolutist kingdom is only symbolic, and has not altered the powers hitherto exercised exclusively by the King.

To understand what has really happened in Bhutan, it is essential to go a little back into history. The Wangchuck dynasty came to power in 1907 by uniting a bunch of warring chieftains. The fourth king in this dynasty, JigmeSingyeWangchuck, assumed power in July 1972 at the young age of 17 following the untimely death of his father. Jigme Wangchuck brought to the throne a wisdom and sagacity that belied his youthfulness and lack of experience. Having laid the foundations of peaceful economic development and political stability with full support from India, he applied his mind seriously to the future course of his kingdom. Until the 1980s, Bhutan had sought to zealously preserve its geographical isolation, preferring to let the world go by.

But this began to gradually change under the fourth king. First, he transferred most of his powers to a nominated Council of Ministers, thereby volitionally diluting the concentration of power in the throne. Then, in 1999, he allowed both television and Internet to make their entry into Bhutan.

Finally, and most dramatically, in December 2005, when he was only 50 years of age, he announced his decision to abdicate from the throne in 2008 in favour of his eldest son, JigmeKhesarNamgyelWangchuck. This announcement was accompanied by a royal command that work on a new constitution must begin immediately with the express purpose of converting Bhutan into a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarchy.

Why did JigmeSingyeWangchuck, whom I had the great privilege of coming to know very well, take these momentous decisions which would curtail his own absolute powers, especially since there was no political restlessness seeking a change of the polity? In fact, most people in this sparsely populated kingdom (population 0.8 million) were happy with their king, and actually had to be persuaded to embrace democracy. The answer quite simply is that JigmeWangchuck had the political incisiveness, rarely seen in monarchs, to pre-empt history. He knew that in a rapidly globalising world, Bhutan could not sustain its isolationist path; he also knew, looking at developments in neighbouring Nepal, that sooner or later there would be a democratic challenge to an absolute monarchy. In view of this, he chose to anticipate the inevitable by initiating change himself. In doing so he also created the most sustainable milieu for the perpetuation of his own dynasty.

Today, democracy is taking roots in Bhutan. The young fifth king, JigmeNamgyelWangchuck, wise beyond his years, and Queen JetsunPema, are loved by the Bhutanese. Prime Minister Tobgay, whose smooth transition from Opposition leader to Prime Minister I have been personally witness to, is an able leader. The National Assembly still functions - especially compared to our raucous standards - with monotonous decorum. Legislators rarely speak out of turn. There is no din in the House. But issues are debated with vigour and conviction. The king addresses the House at the beginning of a session if he chooses to do so.

Otherwise his presence suffices. He remains above the democratic fray, but is very much bound by the Constitution. Although the process is cumbersome, the king can actually be impeached under the Constitution by Parliament. Moreover, the Constitution also mandates that a monarch must compulsorily retire at the age of 65. Democracy, albeit with a strong Bhutanese flavour, has come to stay in the Forbidden Kingdom, and India, as the world's largest democracy, can only welcome it.

Q. The author is most likely to support which of the following statements:-

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

In March 2008, the kingdom of Bhutan, an often invisible Shangri-La tucked away strategically in the Himalayas between India and China, became the world's youngest democracy. An absolute monarchy gave way to a constitutional monarchy, a new Constitution mandating a parliamentary democracy was adopted, and, for the first time, the people of Bhutan voted, on the basis of universal suffrage, to elect a new Parliament consisting of a National Council or Upper House with 25 members, and a National Assembly or Lower House with 47 members. Jigme Thinley became the country's first democratically elected Prime Minister. In the second elections in 2013, his Peace and Prosperity Party was defeated by the People's Democratic Party. Its leader, TsheringTobgay, a young Harvard educated man in his mid-forties, is today the Prime Minister of Bhutan.

When I went as Ambassador of India to Bhutan in 2009, many foreign observers believed that the adoption of parliamentary democracy was more a cosmetic exercise which essentially left untouched the unfettered sway of the monarchy. It is true, of course, that the monarchy continues to enjoy a very high degree of reverence and popularity. But it would be wrong to believe that democracy in this once absolutist kingdom is only symbolic, and has not altered the powers hitherto exercised exclusively by the King.

To understand what has really happened in Bhutan, it is essential to go a little back into history. The Wangchuck dynasty came to power in 1907 by uniting a bunch of warring chieftains. The fourth king in this dynasty, JigmeSingyeWangchuck, assumed power in July 1972 at the young age of 17 following the untimely death of his father. Jigme Wangchuck brought to the throne a wisdom and sagacity that belied his youthfulness and lack of experience. Having laid the foundations of peaceful economic development and political stability with full support from India, he applied his mind seriously to the future course of his kingdom. Until the 1980s, Bhutan had sought to zealously preserve its geographical isolation, preferring to let the world go by.

But this began to gradually change under the fourth king. First, he transferred most of his powers to a nominated Council of Ministers, thereby volitionally diluting the concentration of power in the throne. Then, in 1999, he allowed both television and Internet to make their entry into Bhutan.

Finally, and most dramatically, in December 2005, when he was only 50 years of age, he announced his decision to abdicate from the throne in 2008 in favour of his eldest son, JigmeKhesarNamgyelWangchuck. This announcement was accompanied by a royal command that work on a new constitution must begin immediately with the express purpose of converting Bhutan into a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarchy.

Why did JigmeSingyeWangchuck, whom I had the great privilege of coming to know very well, take these momentous decisions which would curtail his own absolute powers, especially since there was no political restlessness seeking a change of the polity? In fact, most people in this sparsely populated kingdom (population 0.8 million) were happy with their king, and actually had to be persuaded to embrace democracy. The answer quite simply is that JigmeWangchuck had the political incisiveness, rarely seen in monarchs, to pre-empt history. He knew that in a rapidly globalising world, Bhutan could not sustain its isolationist path; he also knew, looking at developments in neighbouring Nepal, that sooner or later there would be a democratic challenge to an absolute monarchy. In view of this, he chose to anticipate the inevitable by initiating change himself. In doing so he also created the most sustainable milieu for the perpetuation of his own dynasty.

Today, democracy is taking roots in Bhutan. The young fifth king, JigmeNamgyelWangchuck, wise beyond his years, and Queen JetsunPema, are loved by the Bhutanese. Prime Minister Tobgay, whose smooth transition from Opposition leader to Prime Minister I have been personally witness to, is an able leader. The National Assembly still functions - especially compared to our raucous standards - with monotonous decorum. Legislators rarely speak out of turn. There is no din in the House. But issues are debated with vigour and conviction. The king addresses the House at the beginning of a session if he chooses to do so.

Otherwise his presence suffices. He remains above the democratic fray, but is very much bound by the Constitution. Although the process is cumbersome, the king can actually be impeached under the Constitution by Parliament. Moreover, the Constitution also mandates that a monarch must compulsorily retire at the age of 65. Democracy, albeit with a strong Bhutanese flavour, has come to stay in the Forbidden Kingdom, and India, as the world's largest democracy, can only welcome it.

Q. Which of the following can be deduced from the passage?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

On the 125th birth anniversary of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, on April 14, India still finds itself unable to induct him into the pantheon of greats unquestioningly. His statue, with its ubiquitous electric blue suit, may be a common sight at bus stands, bastis and universities, but it hardly brings out the fact that his life is one that was overshadowed by iconography and idolatry. We forget that Ambedkar was one of modern India's first great economic thinkers, its constitutional draftsman and its first law minister who ensured the codification of Hindu law.

Assimilating Dr. Ambedkar into the national pantheon of the freedom struggle is difficult because his life was one of steady accretion of ideas, of making a stand on rights and of standing up to social wrongs. His biggest fights were with fellow Indians and not with foreign rulers. He led no satyagraha against the British, he led no march on Delhi, he broke no repressive law to court arrest for it. In fact, his father and ancestors had willingly served in the British Army even in the days of the East India Company. He himself served as a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council. His often stated view was that British rule had come as a liberator for the depressed classes. Despite all this, he was in agreement with the nationalists, that India must be ruled by Indians.

His status in the national pantheon, where he occupies a corner all by himself, and slightly apart from the nationalist heroes of independence, is somewhat like his status in school. He once wrote: "I knew that I was an untouchable, and that untouchables were subjected to certain indignities and discriminations. For instance, I knew that in the school I could not sit in the midst of my classmates according to my rank [in class performance], but that I was to sit in a corner by myself."

This separateness was to lead him to assert in more than one instance, that the depressed classes he represented, were not to be counted among the Hindus. He famously chose to separately represent the depressed classes at the Round Table Conference in the 1930s, where Gandhiji was sent as the sole representative of the Congress. Having secured a separate electorate for the depressed classes, he had to give it up in the face of a fasting Mahatma, whose death he did not want ascribed to those outside the pale of varnashrama dharma. After this, the Poona Pact of 1932 ensured a greater number of seats for the depressed classes, but it was within a common Hindu electorate. Ambedkar never was sure that he had secured a fair bargain.

He never fully forgave Gandhiji for the pressure exerted on him. He told his followers, "There have been many mahatmas in India whose sole object was to remove untouchability and to elevate and absorb the depressed classes, but everyone has failed in their mission. Mahatmas have come, mahatmas have gone but the untouchables have remained as untouchables." Ambedkar told Dalits: "You must abolish your slavery yourselves. Do not depend for its abolition upon god or a superman....We must shape our course ourselves and by ourselves."

The question of whether the depressed classes were to be counted among Hindus or separately, continued to be relevant especially when the country was going to be partitioned on religious lines. There were some Dalit leaders like B. Shyam Sunder, who vociferously said: "We are not Hindus, we have nothing to do with the Hindu caste system, yet we have been included among them by them and for them." With the support of the Nizam of Hyderabad and Master Tara Singh of the Akalis, Shyam Sunder launched the Dalit-Muslim unity movement and urged his people to join hands with Muslims.

The imminent arrival of Independence saw a constituent assembly being elected to draw up a constitution for the new nation. Dr. Ambedkar was first elected to the assembly from an undivided Bengal. Because he lacked the requisite support in his home province of Bombay, he was forced to seek election from Bengal, a province he was unfamiliar with. Throughout the 1940s, Ambedkar and the Congress clashed over issues of the rights and the representation of the depressed classes. Ambedkar was a critic of the party's positions on many an issue, which he believed were inimical to Dalit interests. Therefore, Sardar Patel personally directed the Bombay Congress to select strong Dalit candidates who could defeat Dr. Ambedkar's nominees. Despite the politics, once in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar worked closely with his Congress colleagues in formulating and drafting the Constitution.

Consequent to the announcement of Partition, fresh elections had to be held for only the seats from West Bengal. Dr. Ambedkar would not have possibly been elected again. At this stage he was co-opted by the Congress, into the seat vacated by M.R. Jayakar from Bombay. Dr. Rajendra Prasad wrote to B.G. Kher, then Prime Minister of Bombay and said: "Apart from any other consideration we have found Dr. Ambedkar's work both in Constituent Assembly and the various committees to which he was appointed to be of such an order as to require that we should not be deprived of his services. As you know, he was elected from Bengal and after the division of the province he was ceased to be a member of the Constituent Assembly commencing from the 14th July 1947 and it is therefore necessary that he should be elected immediately." Even Sardar Patel stepped in to persuade both Kher and G.P. Mavalankar, who was otherwise slated to fill in the vacancy caused by Jayakar.

It is against these adverse circumstances, that we must evaluate Ambedkar's achievements in the Constituent Assembly. He walked a tightrope, between securing a modern society for all Indians and ensuring that a modern state stabilised around a constitutional architecture of social change. Granville Austin has rightly described the Indian Constitution drafted by Ambedkar as "first and foremost a social document.... The majority of India's constitutional provisions are either directly arrived at furthering the aim of social revolution or attempt to foster this revolution by establishing conditions necessary for its achievement."

The Constituent Assembly was the hallowed ground from which Ambedkar made his most lasting contribution to all people of independent India, Dalit, savarna and non-Hindu alike. As chairman of the drafting committee, it was his interventions in the debates of the assembly that were soon to become definitive expositions on the intent of the framers. He also joined Nehru's cabinet as the first Law Minister of independent India.

He explained to the Assembly, "On the 26th January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognising the principle of one-man-one-vote and one-vote-one-value. In our social and economic life, we shall by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one-man-one-value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril..."

Despite his insistence on individual liberties being enshrined as fundamental rights, Ambedkar was a realist as to their worth as guarantees. He said: "The prevalent view is that once the rights are enacted in law then they are safeguarded. This again is an unwarranted assumption. As experience proves, rights are protected not by law but by social and moral conscience of the society."

Ambedkar's constitution was barely finished and adopted, when he plunged into piloting the Hindu Code Bill. There was opposition from the President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, as well as a host of Congressmen like PattabhiSitaramayya, but Ambedkar kept pushing for the passage of the Act, by the Constituent Assembly, which functioned as an interim parliament. Nehru was advised by RajagopalaAyyangar and others that it was better to wait till after the general election of 1952. When it became apparent that the bill was going to be deferred, Ambedkar resigned in protest from the cabinet in September 1951. The Hindu Code Bill finally came about in 1956.

In 1952, in independent India's first general election, he was defeated from the Bombay North Constituency by a Dalit from the Congress. Though he was elected to the RajyaSabha immediately thereafter, he made a second attempt in 1954 to enter the LokSabha through a by-election for the Bhandara seat. He failed again.

His political battles and his voracious capacity for intellectual work began affecting his health. His spirit to fight on and his spiritual quest though continued undaunted. In the 1930s, his first wife, Ramabai, who was dying, had asked him to take her to Pandharpur on a pilgrimage. The entry of untouchables was barred there. He then promised to build a new Pandharpur outside Hinduism.

After her passing, he declared at Yeola in 1935: "I was born a Hindu, I had no choice. But I will not die a Hindu because I do have a choice." In the twilight of his life, on October 14, 1956, two months before his death, he left Hinduism to become a Buddhist. His Brahmin-born second wife and nearly six lakh of his followers followed suit.

As he lay down for the night on December 5, 1956, Dr. Ambedkar had by his side, the preface to his latest book, The Buddha and his Dhamma. He wanted to work on it but it was not to be. The book was published posthumously as Babasaheb, never woke up and moved into history on December 6, 1956. How do we remember Ambedkar? He gave the nation a constitution that has endured, he forced it to look shamefaced at its own social inequities, and he gave the most oppressed Indians, the hope of a better nation to come. He may not have been a hero of the war of Indian independence, but he is the hero who built an independent India. It is time that we cease to keep him 'slightly apart'.

Q. What is the author's reasoning behind the statement that Mr. Ambedkar's status in the national pantheon is somewhat like his status in school?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

On the 125th birth anniversary of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, on April 14, India still finds itself unable to induct him into the pantheon of greats unquestioningly. His statue, with its ubiquitous electric blue suit, may be a common sight at bus stands, bastis and universities, but it hardly brings out the fact that his life is one that was overshadowed by iconography and idolatry. We forget that Ambedkar was one of modern India's first great economic thinkers, its constitutional draftsman and its first law minister who ensured the codification of Hindu law.

Assimilating Dr. Ambedkar into the national pantheon of the freedom struggle is difficult because his life was one of steady accretion of ideas, of making a stand on rights and of standing up to social wrongs. His biggest fights were with fellow Indians and not with foreign rulers. He led no satyagraha against the British, he led no march on Delhi, he broke no repressive law to court arrest for it. In fact, his father and ancestors had willingly served in the British Army even in the days of the East India Company. He himself served as a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council. His often stated view was that British rule had come as a liberator for the depressed classes. Despite all this, he was in agreement with the nationalists, that India must be ruled by Indians.

His status in the national pantheon, where he occupies a corner all by himself, and slightly apart from the nationalist heroes of independence, is somewhat like his status in school. He once wrote: "I knew that I was an untouchable, and that untouchables were subjected to certain indignities and discriminations. For instance, I knew that in the school I could not sit in the midst of my classmates according to my rank [in class performance], but that I was to sit in a corner by myself."

This separateness was to lead him to assert in more than one instance, that the depressed classes he represented, were not to be counted among the Hindus. He famously chose to separately represent the depressed classes at the Round Table Conference in the 1930s, where Gandhiji was sent as the sole representative of the Congress. Having secured a separate electorate for the depressed classes, he had to give it up in the face of a fasting Mahatma, whose death he did not want ascribed to those outside the pale of varnashrama dharma. After this, the Poona Pact of 1932 ensured a greater number of seats for the depressed classes, but it was within a common Hindu electorate. Ambedkar never was sure that he had secured a fair bargain.

He never fully forgave Gandhiji for the pressure exerted on him. He told his followers, "There have been many mahatmas in India whose sole object was to remove untouchability and to elevate and absorb the depressed classes, but everyone has failed in their mission. Mahatmas have come, mahatmas have gone but the untouchables have remained as untouchables." Ambedkar told Dalits: "You must abolish your slavery yourselves. Do not depend for its abolition upon god or a superman....We must shape our course ourselves and by ourselves."

The question of whether the depressed classes were to be counted among Hindus or separately, continued to be relevant especially when the country was going to be partitioned on religious lines. There were some Dalit leaders like B. Shyam Sunder, who vociferously said: "We are not Hindus, we have nothing to do with the Hindu caste system, yet we have been included among them by them and for them." With the support of the Nizam of Hyderabad and Master Tara Singh of the Akalis, Shyam Sunder launched the Dalit-Muslim unity movement and urged his people to join hands with Muslims.

The imminent arrival of Independence saw a constituent assembly being elected to draw up a constitution for the new nation. Dr. Ambedkar was first elected to the assembly from an undivided Bengal. Because he lacked the requisite support in his home province of Bombay, he was forced to seek election from Bengal, a province he was unfamiliar with. Throughout the 1940s, Ambedkar and the Congress clashed over issues of the rights and the representation of the depressed classes. Ambedkar was a critic of the party's positions on many an issue, which he believed were inimical to Dalit interests. Therefore, Sardar Patel personally directed the Bombay Congress to select strong Dalit candidates who could defeat Dr. Ambedkar's nominees. Despite the politics, once in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar worked closely with his Congress colleagues in formulating and drafting the Constitution.

Consequent to the announcement of Partition, fresh elections had to be held for only the seats from West Bengal. Dr. Ambedkar would not have possibly been elected again. At this stage he was co-opted by the Congress, into the seat vacated by M.R. Jayakar from Bombay. Dr. Rajendra Prasad wrote to B.G. Kher, then Prime Minister of Bombay and said: "Apart from any other consideration we have found Dr. Ambedkar's work both in Constituent Assembly and the various committees to which he was appointed to be of such an order as to require that we should not be deprived of his services. As you know, he was elected from Bengal and after the division of the province he was ceased to be a member of the Constituent Assembly commencing from the 14th July 1947 and it is therefore necessary that he should be elected immediately." Even Sardar Patel stepped in to persuade both Kher and G.P. Mavalankar, who was otherwise slated to fill in the vacancy caused by Jayakar.

It is against these adverse circumstances, that we must evaluate Ambedkar's achievements in the Constituent Assembly. He walked a tightrope, between securing a modern society for all Indians and ensuring that a modern state stabilised around a constitutional architecture of social change. Granville Austin has rightly described the Indian Constitution drafted by Ambedkar as "first and foremost a social document.... The majority of India's constitutional provisions are either directly arrived at furthering the aim of social revolution or attempt to foster this revolution by establishing conditions necessary for its achievement."

The Constituent Assembly was the hallowed ground from which Ambedkar made his most lasting contribution to all people of independent India, Dalit, savarna and non-Hindu alike. As chairman of the drafting committee, it was his interventions in the debates of the assembly that were soon to become definitive expositions on the intent of the framers. He also joined Nehru's cabinet as the first Law Minister of independent India.

He explained to the Assembly, "On the 26th January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognising the principle of one-man-one-vote and one-vote-one-value. In our social and economic life, we shall by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one-man-one-value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril..."

Despite his insistence on individual liberties being enshrined as fundamental rights, Ambedkar was a realist as to their worth as guarantees. He said: "The prevalent view is that once the rights are enacted in law then they are safeguarded. This again is an unwarranted assumption. As experience proves, rights are protected not by law but by social and moral conscience of the society."

Ambedkar's constitution was barely finished and adopted, when he plunged into piloting the Hindu Code Bill. There was opposition from the President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, as well as a host of Congressmen like PattabhiSitaramayya, but Ambedkar kept pushing for the passage of the Act, by the Constituent Assembly, which functioned as an interim parliament. Nehru was advised by RajagopalaAyyangar and others that it was better to wait till after the general election of 1952. When it became apparent that the bill was going to be deferred, Ambedkar resigned in protest from the cabinet in September 1951. The Hindu Code Bill finally came about in 1956.

In 1952, in independent India's first general election, he was defeated from the Bombay North Constituency by a Dalit from the Congress. Though he was elected to the RajyaSabha immediately thereafter, he made a second attempt in 1954 to enter the LokSabha through a by-election for the Bhandara seat. He failed again.

His political battles and his voracious capacity for intellectual work began affecting his health. His spirit to fight on and his spiritual quest though continued undaunted. In the 1930s, his first wife, Ramabai, who was dying, had asked him to take her to Pandharpur on a pilgrimage. The entry of untouchables was barred there. He then promised to build a new Pandharpur outside Hinduism.

After her passing, he declared at Yeola in 1935: "I was born a Hindu, I had no choice. But I will not die a Hindu because I do have a choice." In the twilight of his life, on October 14, 1956, two months before his death, he left Hinduism to become a Buddhist. His Brahmin-born second wife and nearly six lakh of his followers followed suit.

As he lay down for the night on December 5, 1956, Dr. Ambedkar had by his side, the preface to his latest book, The Buddha and his Dhamma. He wanted to work on it but it was not to be. The book was published posthumously as Babasaheb, never woke up and moved into history on December 6, 1956. How do we remember Ambedkar? He gave the nation a constitution that has endured, he forced it to look shamefaced at its own social inequities, and he gave the most oppressed Indians, the hope of a better nation to come. He may not have been a hero of the war of Indian independence, but he is the hero who built an independent India. It is time that we cease to keep him 'slightly apart'.

Q. All of the following statements show author's support for assimilating Dr. Ambedkar in the national pantheon of the freedom struggle except:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The first systems of writing developed and used by the Germanic peoples were runic alphabets. The runes functioned as letters, but they were much more than just letters in the sense in which we today understand the term. Each rune was an ideographic or pictographic symbol of some cosmological principle or power, and to write a rune was to invoke and direct the force for which it stood. Indeed, in every Germanic language, the word “rune” (from Proto-Germanic runo) means both “letter” and “secret” or “mystery,” and its original meaning, which likely predated the adoption of the runic alphabet, may have been simply “(hushed) message.”

Each rune had a name that hinted at the philosophical and magical significance of its visual form and the sound for which it stands, which was almost always the first sound of the rune’s name. For example, the T-rune, called *Tiwaz in the Proto-Germanic language, is named after the god Tiwaz (known as Tyr in the Viking Age). Tiwaz was perceived to dwell within the daytime sky, and, accordingly, the visual form of the T-rune is an arrow pointed upward (which surely also hints at the god’s martial role). The T-rune was often carved as a standalone ideograph, apart from the writing of any particular word, as part of spells cast to ensure victory in battle.

The runic alphabets are called “futharks” after the first six runes (Fehu, Uruz, Thurisaz, Ansuz, Raidho, Kaunan), in much the same way that the word “alphabet” comes from the names of the first two Hebrew letters (Aleph, Beth). There are three principal futharks: the 24-character Elder Futhark, the first fully-formed runic alphabet, whose development had begun by the first century CE and had been completed before the year 400; the 16-character Younger Futhark, which began to diverge from the Elder Futhark around the beginning of the Viking Age (c. 750 CE) and eventually replaced that older alphabet in Scandinavia; and the 33-character Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, which gradually altered and added to the Elder Futhark in England. On some inscriptions, the twenty-four runes of the Elder Futhark were divided into three ættir (Old Norse, “families”) of eight runes each, but the significance of this division is unfortunately unknown.

Runes were traditionally carved onto stone, wood, bone, metal, or some similarly hard surface rather than drawn with ink and pen on parchment. This explains their sharp, angular form, which was well-suited to the medium.

Much of our current knowledge of the meanings the ancient Germanic peoples attributed to the runes comes from the three “Rune Poems,” documents from Iceland, Norway, and England that provide a short stanza about each rune in their respective futharks (the Younger Futhark is treated in the Icelandic and Norwegian Rune Poems, while the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc is discussed in the Old English Rune Poem).

While runologists argue over many of the details of the historical origins of runic writing, there is widespread agreement on a general outline. The runes are presumed to have been derived from one of the many Old Italic alphabets in use among the Mediterranean peoples of the first century CE, who lived to the south of the Germanic tribes. Earlier Germanic sacred symbols, such as those preserved in northern European petroglyphs, were also likely influential in the development of the script.

The earliest possibly runic inscription is found on the Meldorf brooch, which was manufactured in the north of modern-day Germany around 50 CE. The inscription is highly ambiguous, however, and scholars are divided over whether its letters are runic or Roman. The earliest unambiguous runic inscriptions are found on the Vimose comb from Vimose, Denmark and the Øvre Stabu spearhead from southern Norway, both of which date to approximately 160 CE. The earliest known carving of the entire futhark, in order, is that on the Kylver stone from Gotland, Sweden, which dates to roughly 400 CE.

The transmission of writing from southern Europe to northern Europe likely took place via Germanic warbands, the dominant northern European military institution of the period, who would have encountered Italic writing firsthand during campaigns amongst their southerly neighbors. This hypothesis is supported by the association that runes have always had with the god Odin, who, in the Proto-Germanic period, under his original name Woðanaz, was the divine model of the human warband leader and the invisible patron of the warband’s activities. The Roman historian Tacitus tells us that Odin (“Mercury” in the interpretatio romana) was already established as the dominant god in the pantheons of many of the Germanic tribes by the first century.

From the perspective of the ancient Germanic peoples themselves, however, the runes came from no source as mundane as an Old Italic alphabet. The runes were never “invented,” but are instead eternal, pre-existent forces that Odin himself discovered by undergoing a tremendous ordeal.

Q. Which of the following can be inferred from the passage?

a. Runic script was most likely derived from Old Italic script.

b. Runes were not used so much as a simple writing system, but rather as magical signs to be used for charms.

c. In the Proto-Germanic period, the god Tiwaz was associated with war, victory, marriage and the diurnal sky.

d. The knowledge of the meanings attributed to the runes of the Younger Futhark is derived from the three Rune poems.

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight time-delayed miniature camera could be attached. Neubronner's German patent application was initially rejected, but was granted in December 1908 after he produced authenticated photographs taken by his pigeons. He publicized the technique at the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, and sold some images as postcards at the Frankfurt International Aviation Exhibition and at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Initially, the military potential of pigeon photography for aerial reconnaissance appeared attractive. Battlefield tests in the First World War provided encouraging results, but the ancillary technology of mobile dovecotes for messenger pigeons had the greatest impact. Owing to the rapid perfection of aviation during the war, military interest in pigeon photography faded and Neubronner abandoned his experiments. The idea was briefly resurrected in the 1930s by a Swiss clockmaker, and reportedly also by the German and French militaries. Although war pigeons were deployed extensively during the Second World War, it is unclear to what extent, if any, birds were involved in aerial reconnaissance. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) later developed a battery-powered camera designed for espionage pigeon photography; details of its use remain classified.

The construction of sufficiently small and light cameras with a timer mechanism, and the training and handling of the birds to carry the necessary loads, presented major challenges, as did the limited control over the pigeons' position, orientation and speed when the photographs were being taken. In 2004, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) used miniature television cameras attached to falcons and goshawks to obtain live footage, and today some researchers, enthusiasts and artists similarly deploy crittercams with various species of animals.

The first aerial photographs were taken in 1858 by the balloonist Nadar; in 1860 James Wallace Black took the oldest surviving aerial photographs, also from a balloon. As photographic techniques made further progress, at the end of the 19th century some pioneers placed cameras in unmanned flying objects. In the 1880s, Arthur Batut experimented with kite aerial photography. Many others followed him, and high-quality photographs of Boston taken with this method by William Abner Eddy in 1896 became famous. AmedeeDenisse equipped a rocket with a camera and a parachute in 1888, and Alfred Nobel also used rocket photography in 1897.

Homing pigeons were used extensively in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both for civil pigeon post and as war pigeons. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the famous pigeon post of Paris carried up to 50,000 microfilmed telegrams per pigeon flight from Tours into the besieged capital. Altogether 150,000 individual private telegrams and state dispatches were delivered. In an 1889 experiment of the Imperial Russian Technical Society at Saint Petersburg, the chief of the Russian balloon corps took aerial photographs from a balloon and sent the developed collodion film negatives to the ground by pigeon post.

In 1903 Julius Neubronner, an apothecary in the German town of Kronberg near Frankfurt, resumed a practice begun by his father half a century earlier and received prescriptions from a sanatorium in nearby Falkenstein via pigeon post. (The pigeon post was discontinued after three years when the sanatorium was closed.) He delivered urgent medications up to 75 grams (2.6 oz) by the same method, and positioned some of his pigeons with his wholesaler in Frankfurt to profit from faster deliveries himself. When one of his pigeons lost its orientation in fog and mysteriously arrived, well-fed, four weeks late, Neubronner was inspired with the playful idea of equipping his pigeons with automatic cameras to trace their paths. This thought led him to merge his two hobbies into a new "double sport" combining carrier pigeon fancying with amateur photography. (Neubronner later learned that his pigeon had been in the custody of a restaurant chef in Wiesbaden.)

After successfully testing a Ticka watch camera on a train and whilst riding a sled, Neubronner began the development of a light miniature camera that could be fitted to a pigeon's breast by means of a harness and an aluminum cuirass. Using wooden camera models which weighed 30 to 75 grams (1.1 to 2.6 oz), the pigeons were carefully trained for their load. To take an aerial photograph, Neubronner carried a pigeon to a location up to about 100 kilometres (60 mi) from its home, where it was equipped with a camera and released. The bird, keen to be relieved of its burden, would typically fly home on a direct route, at a height of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft).[10] A pneumatic system in the camera controlled the time delay before a photograph was taken. To accommodate the burdened pigeon, the dovecote had a spacious, elastic landing board and a large entry hole.

According to Neubronner, there were a dozen different models of his camera. In 1907 he had sufficient success to apply for a patent. Initially his invention "Method of and Means for Taking Photographs of Landscapes from Above" was rejected by the German patent office as impossible, but after presentation of authenticated photographs the patent was granted in December 1908. (The rejection was based on a misconception about the carrying capacity of domestic pigeons.) The technology became widely known through Neubronner's participation in the 1909 International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden and the 1909 International Aviation Exhibition in Frankfurt. Spectators in Dresden could watch the arrival of the pigeons, and the aerial photographs they brought back were turned into postcards. Neubronner's photographs won prizes in Dresden as well as at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Q. Among the following options, who used pigeons to transfer film negatives?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Pigeon photography is an aerial photography technique invented in 1907 by the German apothecary Julius Neubronner, who also used pigeons to deliver medications. A homing pigeon was fitted with an aluminium breast harness to which a lightweight time-delayed miniature camera could be attached. Neubronner's German patent application was initially rejected, but was granted in December 1908 after he produced authenticated photographs taken by his pigeons. He publicized the technique at the 1909 Dresden International Photographic Exhibition, and sold some images as postcards at the Frankfurt International Aviation Exhibition and at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Initially, the military potential of pigeon photography for aerial reconnaissance appeared attractive. Battlefield tests in the First World War provided encouraging results, but the ancillary technology of mobile dovecotes for messenger pigeons had the greatest impact. Owing to the rapid perfection of aviation during the war, military interest in pigeon photography faded and Neubronner abandoned his experiments. The idea was briefly resurrected in the 1930s by a Swiss clockmaker, and reportedly also by the German and French militaries. Although war pigeons were deployed extensively during the Second World War, it is unclear to what extent, if any, birds were involved in aerial reconnaissance. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) later developed a battery-powered camera designed for espionage pigeon photography; details of its use remain classified.

The construction of sufficiently small and light cameras with a timer mechanism, and the training and handling of the birds to carry the necessary loads, presented major challenges, as did the limited control over the pigeons' position, orientation and speed when the photographs were being taken. In 2004, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) used miniature television cameras attached to falcons and goshawks to obtain live footage, and today some researchers, enthusiasts and artists similarly deploy crittercams with various species of animals.

The first aerial photographs were taken in 1858 by the balloonist Nadar; in 1860 James Wallace Black took the oldest surviving aerial photographs, also from a balloon. As photographic techniques made further progress, at the end of the 19th century some pioneers placed cameras in unmanned flying objects. In the 1880s, Arthur Batut experimented with kite aerial photography. Many others followed him, and high-quality photographs of Boston taken with this method by William Abner Eddy in 1896 became famous. AmedeeDenisse equipped a rocket with a camera and a parachute in 1888, and Alfred Nobel also used rocket photography in 1897.

Homing pigeons were used extensively in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both for civil pigeon post and as war pigeons. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the famous pigeon post of Paris carried up to 50,000 microfilmed telegrams per pigeon flight from Tours into the besieged capital. Altogether 150,000 individual private telegrams and state dispatches were delivered. In an 1889 experiment of the Imperial Russian Technical Society at Saint Petersburg, the chief of the Russian balloon corps took aerial photographs from a balloon and sent the developed collodion film negatives to the ground by pigeon post.

In 1903 Julius Neubronner, an apothecary in the German town of Kronberg near Frankfurt, resumed a practice begun by his father half a century earlier and received prescriptions from a sanatorium in nearby Falkenstein via pigeon post. (The pigeon post was discontinued after three years when the sanatorium was closed.) He delivered urgent medications up to 75 grams (2.6 oz) by the same method, and positioned some of his pigeons with his wholesaler in Frankfurt to profit from faster deliveries himself. When one of his pigeons lost its orientation in fog and mysteriously arrived, well-fed, four weeks late, Neubronner was inspired with the playful idea of equipping his pigeons with automatic cameras to trace their paths. This thought led him to merge his two hobbies into a new "double sport" combining carrier pigeon fancying with amateur photography. (Neubronner later learned that his pigeon had been in the custody of a restaurant chef in Wiesbaden.)

After successfully testing a Ticka watch camera on a train and whilst riding a sled,Neubronner began the development of a light miniature camera that could be fitted to a pigeon's breast by means of a harness and an aluminum cuirass. Using wooden camera models which weighed 30 to 75 grams (1.1 to 2.6 oz), the pigeons were carefully trained for their load. To take an aerial photograph, Neubronner carried a pigeon to a location up to about 100 kilometres (60 mi) from its home, where it was equipped with a camera and released. The bird, keen to be relieved of its burden, would typically fly home on a direct route, at a height of 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft).[10] A pneumatic system in the camera controlled the time delay before a photograph was taken. To accommodate the burdened pigeon, the dovecote had a spacious, elastic landing board and a large entry hole.

According to Neubronner, there were a dozen different models of his camera. In 1907 he had sufficient success to apply for a patent. Initially his invention "Method of and Means for Taking Photographs of Landscapes from Above" was rejected by the German patent office as impossible, but after presentation of authenticated photographs the patent was granted in December 1908. (The rejection was based on a misconception about the carrying capacity of domestic pigeons). The technology became widely known through Neubronner's participation in the 1909 International Photographic Exhibition in Dresden and the 1909 International Aviation Exhibition in Frankfurt. Spectators in Dresden could watch the arrival of the pigeons, and the aerial photographs they brought back were turned into postcards. Neubronner's photographs won prizes in Dresden as well as at the 1910 and 1911 Paris Air Shows.

Q. Pigeons were extensively used in 19th and early 20th century for all of the following EXCEPT:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

In March 2008, the kingdom of Bhutan, an often invisible Shangri-La tucked away strategically in the Himalayas between India and China, became the world's youngest democracy. An absolute monarchy gave way to a constitutional monarchy, a new Constitution mandating a parliamentary democracy was adopted, and, for the first time, the people of Bhutan voted, on the basis of universal suffrage, to elect a new Parliament consisting of a National Council or Upper House with 25 members, and a National Assembly or Lower House with 47 members. Jigme Thinley became the country's first democratically elected Prime Minister. In the second elections in 2013, his Peace and Prosperity Party was defeated by the People's Democratic Party. Its leader, TsheringTobgay, a young Harvard educated man in his mid-forties, is today the Prime Minister of Bhutan.

When I went as Ambassador of India to Bhutan in 2009, many foreign observers believed that the adoption of parliamentary democracy was more a cosmetic exercise which essentially left untouched the unfettered sway of the monarchy. It is true, of course, that the monarchy continues to enjoy a very high degree of reverence and popularity. But it would be wrong to believe that democracy in this once absolutist kingdom is only symbolic, and has not altered the powers hitherto exercised exclusively by the King.

To understand what has really happened in Bhutan, it is essential to go a little back into history. The Wangchuck dynasty came to power in 1907 by uniting a bunch of warring chieftains. The fourth king in this dynasty, JigmeSingyeWangchuck, assumed power in July 1972 at the young age of 17 following the untimely death of his father. Jigme Wangchuck brought to the throne a wisdom and sagacity that belied his youthfulness and lack of experience. Having laid the foundations of peaceful economic development and political stability with full support from India, he applied his mind seriously to the future course of his kingdom. Until the 1980s, Bhutan had sought to zealously preserve its geographical isolation, preferring to let the world go by.

But this began to gradually change under the fourth king. First, he transferred most of his powers to a nominated Council of Ministers, thereby volitionally diluting the concentration of power in the throne. Then, in 1999, he allowed both television and Internet to make their entry into Bhutan.

Finally, and most dramatically, in December 2005, when he was only 50 years of age, he announced his decision to abdicate from the throne in 2008 in favour of his eldest son, JigmeKhesarNamgyelWangchuck. This announcement was accompanied by a royal command that work on a new constitution must begin immediately with the express purpose of converting Bhutan into a parliamentary democracy with a constitutional monarchy.

Why did JigmeSingyeWangchuck, whom I had the great privilege of coming to know very well, take these momentous decisions which would curtail his own absolute powers, especially since there was no political restlessness seeking a change of the polity? In fact, most people in this sparsely populated kingdom (population 0.8 million) were happy with their king, and actually had to be persuaded to embrace democracy. The answer quite simply is that JigmeWangchuck had the political incisiveness, rarely seen in monarchs, to pre-empt history. He knew that in a rapidly globalising world, Bhutan could not sustain its isolationist path; he also knew, looking at developments in neighbouring Nepal, that sooner or later there would be a democratic challenge to an absolute monarchy. In view of this, he chose to anticipate the inevitable by initiating change himself. In doing so he also created the most sustainable milieu for the perpetuation of his own dynasty.

Today, democracy is taking roots in Bhutan. The young fifth king, JigmeNamgyelWangchuck, wise beyond his years, and Queen JetsunPema, are loved by the Bhutanese. Prime Minister Tobgay, whose smooth transition from Opposition leader to Prime Minister I have been personally witness to, is an able leader. The National Assembly still functions - especially compared to our raucous standards - with monotonous decorum. Legislators rarely speak out of turn. There is no din in the House. But issues are debated with vigour and conviction. The king addresses the House at the beginning of a session if he chooses to do so.

Otherwise his presence suffices. He remains above the democratic fray, but is very much bound by the Constitution. Although the process is cumbersome, the king can actually be impeached under the Constitution by Parliament. Moreover, the Constitution also mandates that a monarch must compulsorily retire at the age of 65. Democracy, albeit with a strong Bhutanese flavour, has come to stay in the Forbidden Kingdom, and India, as the world's largest democracy, can only welcome it.

Q. The primary purpose of the passage is: