Practice Test for IIFT - 6 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - Practice Test for IIFT - 6

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The endless struggle between the flesh and the spirit found an end in Greek art. The Greek artists were unaware of it. They were spiritual materialists, never denying the importance of the body and ever seeing in the body a spiritual significance. Mysticism on the whole was alien to the Greeks, thinkers as they were. Thought and mysticism never go well together and there is little symbolism in Greek art. Athena was not a symbol of wisdom but an embodiment of it and her statues were beautiful grave women, whose seriousness might mark them as wise, but who were marked in no other way. The Apollo Belvedere is not a symbol of the sun, nor the Versailles Artemis of the moon. There could be nothing less akin to the ways of symbolism than their beautiful, normal humanity. Nor did decoration really interest the Greeks. In all their art they were preoccupied with what they wanted to express, not with ways of expressing it, and lovely expression, merely as lovely expression, did not appeal to them at all.

Greek art is intellectual art, the art of men who were clear and lucid thinkers, and it is therefore plain art. Artists than whom the world has never seen greater, men endowed with the spirit's best gift, found their natural method of expression in the simplicity and clarity which are the endowment of the unclouded reason. “Nothing in excess,” the Greek axiom of art, is the dictum of men who would brush aside all obscuring, entangling superfluity, and see clearly: plainly, unadorned, what they wished to express. Structure belongs in an especial degree to the province of the mind in art, and architectonics were pre-eminently a mark of the Greek. The power that made a unified whole of the trilogy of a Greek tragedy, that envisioned the sure, precise, decisive scheme of the Greek statue, found its most conspicuous expression in Greek architecture. The Greek temple is the creation, par excellence, of mind and spirit in equilibrium.

A Hindoo temple is a conglomeration of adornment. The lines of the building are completely hidden by the decorations. Sculptured figures and ornaments crowd its surface, stand out from it in thick masses, break it up into a bewildering series of irregular tiers. It is not a unity but a collection, rich, confused. It looks like something not planned but built this way and that as the ornament required. The conviction underlying it can be perceived: each bit of the exquisitely wrought detail had a mystical meaning and the temple‟s exterior was important only as a means for the artist to inscribe thereon the symbols of the truth. It is decoration, not architecture.

Again, the gigantic temples of Egypt, those massive immensities of granite which look as if only the power that moves in the earthquake were mighty enough to bring them into existence, are something other than the creation of geometry balanced by beauty. The science and the spirit are there, but what is there most of all is force, inhuman force, calm but tremendous, overwhelming. It reduces to nothingness all that belongs to man. He is annihilated. The Egyptian architects were possessed by the consciousness of the awful, irresistible domination of the ways of nature; they had no thought to give to the insignificant atom that was man.

Greek architecture of the great age is the expression of men who were, first of all, intellectual artists, kept firmly within the visible world by their mind, but, only second to that, lovers of the human world. The Greek temple is the perfect expression of the pure intellect illumined by the spirit. No other great buildings anywhere approach its simplicity. In the Parthenon straight columns rise to plain capitals; a pediment is sculptured in bold, relief; there is nothing more. And yet-here is the Greek miracle-this absolute simplicity of structure is alone in majesty of beauty among all the temples and cathedrals and palaces of the world. Majestic but human, truly Greek. No superhuman force as in Egypt; no strange supernatural shapes as in India; the Parthenon is the home of humanity! At ease, calm, ordered, sure of itself and the world. The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength. They set their temples on the summit of a hill overlooking the wide sea, outlined against the circle of the sky. They would build what was more beautiful than hill and sea and sky and greater than all these. It matters not at all if the temple is large or small; one never thinks of the size. It matters not how much it is in ruins. A few white columns dominate the lofty height at Sunion as securely as the greatmass of the Parthenon dominates all the sweep of sea and land around Athens. To the Greek architect man was the master of the world. His mind could understand its laws; his spirit could discover its beauty.

Q. From the passage, which of the following combinations can be inferred to be correct?

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The endless struggle between the flesh and the spirit found an end in Greek art. The Greek artists were unaware of it. They were spiritual materialists, never denying the importance of the body and ever seeing in the body a spiritual significance. Mysticism on the whole was alien to the Greeks, thinkers as they were. Thought and mysticism never go well together and there is little symbolism in Greek art. Athena was not a symbol of wisdom but an embodiment of it and her statues were beautiful grave women, whose seriousness might mark them as wise, but who were marked in no other way. The Apollo Belvedere is not a symbol of the sun, nor the Versailles Artemis of the moon. There could be nothing less akin to the ways of symbolism than their beautiful, normal humanity. Nor did decoration really interest the Greeks. In all their art they were preoccupied with what they wanted to express, not with ways of expressing it, and lovely expression, merely as lovely expression, did not appeal to them at all.

Greek art is intellectual art, the art of men who were clear and lucid thinkers, and it is therefore plain art. Artists than whom the world has never seen greater, men endowed with the spirit's best gift, found their natural method of expression in the simplicity and clarity which are the endowment of the unclouded reason. “Nothing in excess,” the Greek axiom of art, is the dictum of men who would brush aside all obscuring, entangling superfluity, and see clearly: plainly, unadorned, what they wished to express. Structure belongs in an especial degree to the province of the mind in art, and architectonics were pre-eminently a mark of the Greek. The power that made a unified whole of the trilogy of a Greek tragedy, that envisioned the sure, precise, decisive scheme of the Greek statue, found its most conspicuous expression in Greek architecture. The Greek temple is the creation, par excellence, of mind and spirit in equilibrium.

A Hindoo temple is a conglomeration of adornment. The lines of the building are completely hidden by the decorations. Sculptured figures and ornaments crowd its surface, stand out from it in thick masses, break it up into a bewildering series of irregular tiers. It is not a unity but a collection, rich, confused. It looks like something not planned but built this way and that as the ornament required. The conviction underlying it can be perceived: each bit of the exquisitely wrought detail had a mystical meaning and the temple‟s exterior was important only as a means for the artist to inscribe thereon the symbols of the truth. It is decoration, not architecture.

Again, the gigantic temples of Egypt, those massive immensities of granite which look as if only the power that moves in the earthquake were mighty enough to bring them into existence, are something other than the creation of geometry balanced by beauty. The science and the spirit are there, but what is there most of all is force, inhuman force, calm but tremendous, overwhelming. It reduces to nothingness all that belongs to man. He is annihilated. The Egyptian architects were possessed by the consciousness of the awful, irresistible domination of the ways of nature; they had no thought to give to the insignificant atom that was man.

Greek architecture of the great age is the expression of men who were, first of all, intellectual artists, kept firmly within the visible world by their mind, but, only second to that, lovers of the human world. The Greek temple is the perfect expression of the pure intellect illumined by the spirit. No other great buildings anywhere approach its simplicity. In the Parthenon straight columns rise to plain capitals; a pediment is sculptured in bold, relief; there is nothing more. And yet-here is the Greek miracle-this absolute simplicity of structure is alone in majesty of beauty among all the temples and cathedrals and palaces of the world. Majestic but human, truly Greek. No superhuman force as in Egypt; no strange supernatural shapes as in India; the Parthenon is the home of humanity! At ease, calm, ordered, sure of itself and the world. The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength. They set their temples on the summit of a hill overlooking the wide sea, outlined against the circle of the sky. They would build what was more beautiful than hill and sea and sky and greater than all these. It matters not at all if the temple is large or small; one never thinks of the size. It matters not how much it is in ruins. A few white columns dominate the lofty height at Sunion as securely as the greatmass of the Parthenon dominates all the sweep of sea and land around Athens. To the Greek architect man was the master of the world. His mind could understand its laws; his spirit could discover its beauty.

Q. Which of the following is NOT a characteristic of Greek architecture, according to the passage?

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The endless struggle between the flesh and the spirit found an end in Greek art. The Greek artists were unaware of it. They were spiritual materialists, never denying the importance of the body and ever seeing in the body a spiritual significance. Mysticism on the whole was alien to the Greeks, thinkers as they were. Thought and mysticism never go well together and there is little symbolism in Greek art. Athena was not a symbol of wisdom but an embodiment of it and her statues were beautiful grave women, whose seriousness might mark them as wise, but who were marked in no other way. The Apollo Belvedere is not a symbol of the sun, nor the Versailles Artemis of the moon. There could be nothing less akin to the ways of symbolism than their beautiful, normal humanity. Nor did decoration really interest the Greeks. In all their art they were preoccupied with what they wanted to express, not with ways of expressing it, and lovely expression, merely as lovely expression, did not appeal to them at all.

Greek art is intellectual art, the art of men who were clear and lucid thinkers, and it is therefore plain art. Artists than whom the world has never seen greater, men endowed with the spirit's best gift, found their natural method of expression in the simplicity and clarity which are the endowment of the unclouded reason. “Nothing in excess,” the Greek axiom of art, is the dictum of men who would brush aside all obscuring, entangling superfluity, and see clearly: plainly, unadorned, what they wished to express. Structure belongs in an especial degree to the province of the mind in art, and architectonics were pre-eminently a mark of the Greek. The power that made a unified whole of the trilogy of a Greek tragedy, that envisioned the sure, precise, decisive scheme of the Greek statue, found its most conspicuous expression in Greek architecture. The Greek temple is the creation, par excellence, of mind and spirit in equilibrium.

A Hindoo temple is a conglomeration of adornment. The lines of the building are completely hidden by the decorations. Sculptured figures and ornaments crowd its surface, stand out from it in thick masses, break it up into a bewildering series of irregular tiers. It is not a unity but a collection, rich, confused. It looks like something not planned but built this way and that as the ornament required. The conviction underlying it can be perceived: each bit of the exquisitely wrought detail had a mystical meaning and the temple‟s exterior was important only as a means for the artist to inscribe thereon the symbols of the truth. It is decoration, not architecture.

Again, the gigantic temples of Egypt, those massive immensities of granite which look as if only the power that moves in the earthquake were mighty enough to bring them into existence, are something other than the creation of geometry balanced by beauty. The science and the spirit are there, but what is there most of all is force, inhuman force, calm but tremendous, overwhelming. It reduces to nothingness all that belongs to man. He is annihilated. The Egyptian architects were possessed by the consciousness of the awful, irresistible domination of the ways of nature; they had no thought to give to the insignificant atom that was man.

Greek architecture of the great age is the expression of men who were, first of all, intellectual artists, kept firmly within the visible world by their mind, but, only second to that, lovers of the human world. The Greek temple is the perfect expression of the pure intellect illumined by the spirit. No other great buildings anywhere approach its simplicity. In the Parthenon straight columns rise to plain capitals; a pediment is sculptured in bold, relief; there is nothing more. And yet-here is the Greek miracle-this absolute simplicity of structure is alone in majesty of beauty among all the temples and cathedrals and palaces of the world. Majestic but human, truly Greek. No superhuman force as in Egypt; no strange supernatural shapes as in India; the Parthenon is the home of humanity! At ease, calm, ordered, sure of itself and the world. The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength. They set their temples on the summit of a hill overlooking the wide sea, outlined against the circle of the sky. They would build what was more beautiful than hill and sea and sky and greater than all these. It matters not at all if the temple is large or small; one never thinks of the size. It matters not how much it is in ruins. A few white columns dominate the lofty height at Sunion as securely as the greatmass of the Parthenon dominates all the sweep of sea and land around Athens. To the Greek architect man was the master of the world. His mind could understand its laws; his spirit could discover its beauty.

Q. According to the passage, what conception of man can be inferred from Egyptian architecture?

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The endless struggle between the flesh and the spirit found an end in Greek art. The Greek artists were unaware of it. They were spiritual materialists, never denying the importance of the body and ever seeing in the body a spiritual significance. Mysticism on the whole was alien to the Greeks, thinkers as they were. Thought and mysticism never go well together and there is little symbolism in Greek art. Athena was not a symbol of wisdom but an embodiment of it and her statues were beautiful grave women, whose seriousness might mark them as wise, but who were marked in no other way. The Apollo Belvedere is not a symbol of the sun, nor the Versailles Artemis of the moon. There could be nothing less akin to the ways of symbolism than their beautiful, normal humanity. Nor did decoration really interest the Greeks. In all their art they were preoccupied with what they wanted to express, not with ways of expressing it, and lovely expression, merely as lovely expression, did not appeal to them at all.

Greek art is intellectual art, the art of men who were clear and lucid thinkers, and it is therefore plain art. Artists than whom the world has never seen greater, men endowed with the spirit's best gift, found their natural method of expression in the simplicity and clarity which are the endowment of the unclouded reason. “Nothing in excess,” the Greek axiom of art, is the dictum of men who would brush aside all obscuring, entangling superfluity, and see clearly: plainly, unadorned, what they wished to express. Structure belongs in an especial degree to the province of the mind in art, and architectonics were pre-eminently a mark of the Greek. The power that made a unified whole of the trilogy of a Greek tragedy, that envisioned the sure, precise, decisive scheme of the Greek statue, found its most conspicuous expression in Greek architecture. The Greek temple is the creation, par excellence, of mind and spirit in equilibrium.

A Hindoo temple is a conglomeration of adornment. The lines of the building are completely hidden by the decorations. Sculptured figures and ornaments crowd its surface, stand out from it in thick masses, break it up into a bewildering series of irregular tiers. It is not a unity but a collection, rich, confused. It looks like something not planned but built this way and that as the ornament required. The conviction underlying it can be perceived: each bit of the exquisitely wrought detail had a mystical meaning and the temple's exterior was important only as a means for the artist to inscribe thereon the symbols of the truth. It is decoration, not architecture.

Again, the gigantic temples of Egypt, those massive immensities of granite which look as if only the power that moves in the earthquake were mighty enough to bring them into existence, are something other than the creation of geometry balanced by beauty. The science and the spirit are there, but what is there most of all is force, inhuman force, calm but tremendous, overwhelming. It reduces to nothingness all that belongs to man. He is annihilated. The Egyptian architects were possessed by the consciousness of the awful, irresistible domination of the ways of nature; they had no thought to give to the insignificant atom that was man.

Greek architecture of the great age is the expression of men who were, first of all, intellectual artists, kept firmly within the visible world by their mind, but, only second to that, lovers of the human world. The Greek temple is the perfect expression of the pure intellect illumined by the spirit. No other great buildings anywhere approach its simplicity. In the Parthenon straight columns rise to plain capitals; a pediment is sculptured in bold, relief; there is nothing more. And yet-here is the Greek miracle-this absolute simplicity of structure is alone in majesty of beauty among all the temples and cathedrals and palaces of the world. Majestic but human, truly Greek. No superhuman force as in Egypt; no strange supernatural shapes as in India; the Parthenon is the home of humanity! At ease, calm, ordered, sure of itself and the world. The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength. They set their temples on the summit of a hill overlooking the wide sea, outlined against the circle of the sky. They would build what was more beautiful than hill and sea and sky and greater than all these. It matters not at all if the temple is large or small; one never thinks of the size. It matters not how much it is in ruins. A few white columns dominate the lofty height at Sunion as securely as the greatmass of the Parthenon dominates all the sweep of sea and land around Athens. To the Greek architect man was the master of the world. His mind could understand its laws; his spirit could discover its beauty.

Q. According to the passage, which of the following best explains why there is little symbolism in Greek art?

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The endless struggle between the flesh and the spirit found an end in Greek art. The Greek artists were unaware of it. They were spiritual materialists, never denying the importance of the body and ever seeing in the body a spiritual significance. Mysticism on the whole was alien to the Greeks, thinkers as they were. Thought and mysticism never go well together and there is little symbolism in Greek art. Athena was not a symbol of wisdom but an embodiment of it and her statues were beautiful grave women, whose seriousness might mark them as wise, but who were marked in no other way. The Apollo Belvedere is not a symbol of the sun, nor the Versailles Artemis of the moon. There could be nothing less akin to the ways of symbolism than their beautiful, normal humanity. Nor did decoration really interest the Greeks. In all their art they were preoccupied with what they wanted to express, not with ways of expressing it, and lovely expression, merely as lovely expression, did not appeal to them at all.

Greek art is intellectual art, the art of men who were clear and lucid thinkers, and it is therefore plain art. Artists than whom the world has never seen greater, men endowed with the spirit's best gift, found their natural method of expression in the simplicity and clarity which are the endowment of the unclouded reason. “Nothing in excess,” the Greek axiom of art, is the dictum of men who would brush aside all obscuring, entangling superfluity, and see clearly: plainly, unadorned, what they wished to express. Structure belongs in an especial degree to the province of the mind in art, and architectonics were pre-eminently a mark of the Greek. The power that made a unified whole of the trilogy of a Greek tragedy, that envisioned the sure, precise, decisive scheme of the Greek statue, found its most conspicuous expression in Greek architecture. The Greek temple is the creation, par excellence, of mind and spirit in equilibrium.

A Hindoo temple is a conglomeration of adornment. The lines of the building are completely hidden by the decorations. Sculptured figures and ornaments crowd its surface, stand out from it in thick masses, break it up into a bewildering series of irregular tiers. It is not a unity but a collection, rich, confused. It looks like something not planned but built this way and that as the ornament required. The conviction underlying it can be perceived: each bit of the exquisitely wrought detail had a mystical meaning and the temple's exterior was important only as a means for the artist to inscribe thereon the symbols of the truth. It is decoration, not architecture.

Again, the gigantic temples of Egypt, those massive immensities of granite which look as if only the power that moves in the earthquake were mighty enough to bring them into existence, are something other than the creation of geometry balanced by beauty. The science and the spirit are there, but what is there most of all is force, inhuman force, calm but tremendous, overwhelming. It reduces to nothingness all that belongs to man. He is annihilated. The Egyptian architects were possessed by the consciousness of the awful, irresistible domination of the ways of nature; they had no thought to give to the insignificant atom that was man.

Greek architecture of the great age is the expression of men who were, first of all, intellectual artists, kept firmly within the visible world by their mind, but, only second to that, lovers of the human world. The Greek temple is the perfect expression of the pure intellect illumined by the spirit. No other great buildings anywhere approach its simplicity. In the Parthenon straight columns rise to plain capitals; a pediment is sculptured in bold, relief; there is nothing more. And yet-here is the Greek miracle-this absolute simplicity of structure is alone in majesty of beauty among all the temples and cathedrals and palaces of the world. Majestic but human, truly Greek. No superhuman force as in Egypt; no strange supernatural shapes as in India; the Parthenon is the home of humanity! At ease, calm, ordered, sure of itself and the world. The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength. They set their temples on the summit of a hill overlooking the wide sea, outlined against the circle of the sky. They would build what was more beautiful than hill and sea and sky and greater than all these. It matters not at all if the temple is large or small; one never thinks of the size. It matters not how much it is in ruins. A few white columns dominate the lofty height at Sunion as securely as the greatmass of the Parthenon dominates all the sweep of sea and land around Athens. To the Greek architect man was the master of the world. His mind could understand its laws; his spirit could discover its beauty.

Q. “The Greeks flung a challenge to nature in the fullness of their joyous strength.” Which of the following best captures the” challenge that is being referred to?

Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The tight calendar had calmed hint, as did the constant exertion of his authority as a judge. How he relished his powerover the classes that had kept his family pinned under their heels for centuries - like the stenographer, for example, who was a Brahmin. There he was, now crawling into a tiny tent to the side, and there was Jemubhai reclining like a king in a bed carved out of teak, hung with mosquito netting."Bed tea", the cook would shout "Baaadtee". He would sit up to drink.6.30: he'd bathe in water that had been heated over the fire so it was redolent with the smell of wood smoke and flocked with ash. With a dusting of powder he graced his newly washed face, with a daub of pomade, his hair. Crunched up toast like charcoal from having been toasted upon the flame, with marmalade over the burn.8.30: he rode into the fields with the local officials and everyone else in the village going along for fun. Followed by an orderly holding an umbrella over his head to shield him from the glare, he measured the fields and checked to make sure his yield estimate matched the headman's statement. Farms were growing less than ten maunds an acre of rice or wheat, and at two rupees a maund, every single man in a village, sometimes, was in debt to the bania.

(Nobody knew that Jemuhhai himself was noosed, of course, that long ago in the little town of Piphit in Gujarat, moneylenders had sniffed out in him a winning combination of ambition and poverty that they still sat waiting cross-legged on a soiled mat in the market, snapping their toes, cracking their knuckles in anticipation of repayment) 2.00: after lunch, the judge sat at his desk under a tree to try cases, usually in a cross mood, for he disliked the informality, hated the splotch of leaf shadow on him imparting an untidy mongrel look. Also, there was a worse aspect of contamination and corruption; he heard cases in Hindi, but they were recorded in Urdu by the stenographer and translated by the judge into a second record in English, although his own command of Hindi and Urdu was tenuous; the witnesses who couldn't read at all put their thumbprints at the bottom of "Read Over and Acknowledged Correct", as instructed.

Nobody could be sure how much of the truth had fallen between languages, between languages and illiteracy; the clarity that justice demanded was nonexistent. Still, despite the leaf shadow and language confusion, he acquired a fearsome reputation for his speech that seemed to belong to no language at all, and for his face like a mask that conveyed something beyond human fallibility. The expression and manner honed here would carry him, eventually, all the way to the high court in Lucknow where, annoyed by lawless pigeons shuttlecocking about those tall, shadowy halls, he would preside, white powdered wig over white powdered face, hammer in hand. His photograph, thus attired, thus annoyed, was still up on the wall, in a parade of history glorifying the progress of Indian law and order.4:30: tea had to be perfect, drop scones made in the frying pan. He would embark on them with forehead wrinkled, as if angrily mulling over something important, and then, as it would into his retirement, the draw of the sweet took over, and his stern workface would hatch an expression of tranquillity. 5:30: out he went into the countryside with his fishing rod or gun. The countryside was full of game; lariats of migratory birds lassoed the sky in October; quail and partridge with lines of babies strung out behind whirred by like nursery toys that emit sound with movement; pheasant - fat foolish creatures, made to be shot - went scurrying, through the bushes. The thunder of gunshot rolled away, the leaves shivered, and he experienced the profound silence that could come only after violence. One thing was always missing, though, the proof of the pudding, the prize of the action, the manliness in manhood, the partridge for the pot, because he returned with - Nothing! He was a terrible shot.8:00. the cook saved his reputation, cooked a chicken, brought it forth, proclaimed it "roast bastard", just as in the Englishman's favourite joke book of natives using incorrect English.

But sometimes, eating that roast bustard, the judge felt the joke might also be on him, and he called for another rum, took a big gulp, and kept eating feeling as if he were eating himself, since he, too, was (was he?) part of the fun.... 9:00: sipping Ovaltine, he filled out the registers with the day's gleanings. The Petromax lantern would be lit - what as noise it made - insects fording the black to dive - bomb him with soft flowers (moths), with iridescence (beetles). Lines, columns, and squares. He realized truth was best looked at in tiny aggregates,for many baby truths could yet add up to one big size unsavory lie. Last, in his diary also to be submitted to his superiors, he recorded the random observations of a cultured man, someone who was observant, schooled in literature as well as economics; and he made up bunting triumphs: two partridge.... one deer with thirty-inch horns....11:00 : he had a hot water bottle in winter, and, in all seasons, to the sound of the wind buffeting the trees and the cook's snoring, he fell asleep.

Q. Which of the following statements is incorrect?

Read the following passage carefullyand answer the questions given at the end.

The tight calendar had calmed hint, as did the constant exertion of his authority as a judge. How he relished his powerover the classes that had kept his family pinned under their heels for centuries - like the stenographer, for example, who was a Brahmin. There he was, now crawling into a tiny tent to the side,and there was Jemubhai reclining like a king in a bed carved out of teak, hung with mosquito netting."Bed tea", the cook would shout "Baaadtee".He would sit up to drink.6.30: he'd bathe in water that had been heated over the fire so it was redolent with the smell of wood smoke and flocked with ash. With a dusting of powder he graced his newly washed face, with a daub of pomade, his hair. Crunched up toast like charcoal from having been toasted upon the flame, with marmalade over the burn.8.30: he rode into the fields with the local officials and everyone else in the village going along for fun. Followed by an orderly holding an umbrella over his head to shield him from the glare, he measured the fields and checked to make sure his yield estimate matched the headman's statement. Farms were growing less than ten maunds an acre of rice or wheat, and at two rupees a maund, every single man in a village, sometimes, was in debt to the bania.

(Nobody knew that Jemuhhai himself was noosed, of course, that long ago in the little town of Piphit in Gujarat, moneylenders had sniffed out in him a winning combination of ambition and poverty … that they still sat waiting cross-legged on a soiled mat in the market, snapping their toes, cracking their knuckles in anticipation of repayment….) 2.00: after lunch, the judge sat at his desk under a tree to try cases, usually in a cross mood, for he disliked the informality, hated the splotch of leaf shadow on him imparting an untidy mongrel look. Also, there was a worse aspect of contamination and corruption; he heard cases in Hindi, but they were recorded in Urdu by the stenographer and translated by the judge into a second record in English, although his own command of Hindi and Urdu was tenuous; the witnesses who couldn't read at all put their thumbprints at the bottom of "Read Over and Acknowledged Correct", as instructed.

Nobody could be sure how much of the truth had fallen between languages, between languages and illiteracy; the clarity that justice demanded was nonexistent. Still, despite the leaf shadow and language confusion, he acquired a fearsome reputation for his speech that seemed to belong to no language at all, and for his face like a mask that conveyed something beyond human fallibility. The expression and manner honed here would carry him, eventually, all the way to the high court in Lucknow where, annoyed by lawless pigeons shuttlecocking about those tall, shadowy halls, he would preside, white powdered wig over white powdered face, hammer in hand. His photograph, thus attired, thus annoyed, was still up on the wall, in a parade of history glorifying the progress of Indian law and order.4:30: tea had to be perfect, drop scones made in the frying pan. He would embark on them with forehead wrinkled, as if angrily mulling over something important, and then, as it would into his retirement, the draw of the sweet took over, and his stern workface would hatch an expression of tranquillity. 5:30: out he went into the countryside with his fishing rod or gun. The countryside was full of game; lariats of migratory birds lassoed the sky in October; quail and partridge with lines of babies strung out behind whirred by like nursery toys that emit sound with movement; pheasant - fat foolish creatures, made to be shot - went scurrying, through the bushes. The thunder of gunshot rolled away, the leaves shivered, and he experienced the profound silence that could come only after violence. One thing was always missing, though, the proof of the pudding, the prize of the action, the manliness in manhood, the partridge for the pot, because he returned with - Nothing! He was a terrible shot.8:00: the cook saved his reputation, cooked a chicken, brought it forth, proclaimed it "roast bastard", just as in the Englishman's favourite joke book of natives using incorrect English.

But sometimes, eating that roast bustard, the judge felt the joke might also be on him, and he called for another rum, took a big gulp, and kept eating feeling as if he were eating himself, since he, too, was (was he?) part of the fun.... 9:00: sipping Ovaltine, he filled out the registers with the day's gleanings. The Petromax lantern would be lit - what as noise it made - insects fording the black to dive - bomb him with soft flowers (moths), with iridescence (beetles). Lines, columns, and squares. He realized truth was best looked at in tiny aggregates,for many baby truths could yet add up to one big size unsavory lie. Last, in his diary also to be submitted to his superiors, he recorded the random observations of a cultured man, someone who was observant, schooled in literature as well as economics; and he made up bunting triumphs: two partridge.... one deer with thirty-inch horns....11:00 : he had a hot water bottle in winter, and, in all seasons, to the sound of the wind buffeting the trees and the cook's snoring, he fell asleep.

Q. What always happened when the judge went to the countryside?

Read the following passage carefullyand answer the questions given at the end.

The tight calendar had calmed hint, as did the constant exertion of his authority as a judge. How he relished his powerover the classes that had kept his family pinned under their heels for centuries - like the stenographer, for example, who was a Brahmin. There he was, now crawling into a tiny tent to the side,and there was Jemubhai reclining like a king in a bed carved out of teak, hung with mosquito netting."Bed tea", the cook would shout "Baaadtee".He would sit up to drink.6.30: he'd bathe in water that had been heated over the fire so it was redolent with the smell of wood smoke and flocked with ash. With a dusting of powder he graced his newly washed face, with a daub of pomade, his hair. Crunched up toast like charcoal from having been toasted upon the flame, with marmalade over the burn.8.30: he rode into the fields with the local officials and everyone else in the village going along for fun. Followed by an orderly holding an umbrella over his head to shield him from the glare, he measured the fields and checked to make sure his yield estimate matched the headman's statement. Farms were growing less than ten maunds an acre of rice or wheat, and at two rupees a maund, every single man in a village, sometimes, was in debt to the bania.

(Nobody knew that Jemuhhai himself was noosed, of course, that long ago in the little town of Piphit in Gujarat, moneylenders had sniffed out in him a winning combination of ambition and poverty … that they still sat waiting cross-legged on a soiled mat in the market, snapping their toes, cracking their knuckles in anticipation of repayment….) 2.00: after lunch, the judge sat at his desk under a tree to try cases, usually in a cross mood, for he disliked the informality, hated the splotch of leaf shadow on him imparting an untidy mongrel look. Also, there was a worse aspect of contamination and corruption; he heard cases in Hindi, but they were recorded in Urdu by the stenographer and translated by the judge into a second record in English, although his own command of Hindi and Urdu was tenuous; the witnesses who couldn't read at all put their thumbprints at the bottom of "Read Over and Acknowledged Correct", as instructed.

Nobody could be sure how much of the truth had fallen between languages, between languages and illiteracy; the clarity that justice demanded was nonexistent. Still, despite the leaf shadow and language confusion, he acquired a fearsome reputation for his speech that seemed to belong to no language at all, and for his face like a mask that conveyed something beyond human fallibility. The expression and manner honed here would carry him, eventually, all the way to the high court in Lucknow where, annoyed by lawless pigeons shuttlecocking about those tall, shadowy halls, he would preside, white powdered wig over white powdered face, hammer in hand. His photograph, thus attired, thus annoyed, was still up on the wall, in a parade of history glorifying the progress of Indian law and order.4:30: tea had to be perfect, drop scones made in the frying pan. He would embark on them with forehead wrinkled, as if angrily mulling over something important, and then, as it would into his retirement, the draw of the sweet took over, and his stern workface would hatch an expression of tranquillity. 5:30: out he went into the countryside with his fishing rod or gun. The countryside was full of game; lariats of migratory birds lassoed the sky in October; quail and partridge with lines of babies strung out behind whirred by like nursery toys that emit sound with movement; pheasant - fat foolish creatures, made to be shot - went scurrying, through the bushes. The thunder of gunshot rolled away, the leaves shivered, and he experienced the profound silence that could come only after violence. One thing was always missing, though, the proof of the pudding, the prize of the action, the manliness in manhood, the partridge for the pot, because he returned with - Nothing! He was a terrible shot.8:00: the cook saved his reputation, cooked a chicken, brought it forth, proclaimed it "roast bastard", just as in the Englishman's favourite joke book of natives using incorrect English.

But sometimes, eating that roast bustard, the judge felt the joke might also be on him, and he called for another rum, took a big gulp, and kept eating feeling as if he were eating himself, since he, too, was (was he?) part of the fun.... 9:00: sipping Ovaltine, he filled out the registers with the day's gleanings. The Petromax lantern would be lit - what as noise it made - insects fording the black to dive - bomb him with soft flowers (moths), with iridescence (beetles). Lines, columns, and squares. He realized truth was best looked at in tiny aggregates,for many baby truths could yet add up to one big size unsavory lie. Last, in his diary also to be submitted to his superiors, he recorded the random observations of a cultured man, someone who was observant, schooled in literature as well as economics; and he made up bunting triumphs: two partridge.... one deer with thirty-inch horns....11:00 : he had a hot water bottle in winter, and, in all seasons, to the sound of the wind buffeting the trees and the cook's snoring, he fell asleep.

Q. People were in "debt to the "bania" because:

Read the following passage carefullyand answer the questions given at the end.

The tight calendar had calmed hint, as did the constant exertion of his authority as a judge. How he relished his powerover the classes that had kept his family pinned under their heels for centuries - like the stenographer, for example, who was a Brahmin. There he was, now crawling into a tiny tent to the side,and there was Jemubhai reclining like a king in a bed carved out of teak, hung with mosquito netting."Bed tea", the cook would shout "Baaadtee".He would sit up to drink.6.30: he'd bathe in water that had been heated over the fire so it was redolent with the smell of wood smoke and flocked with ash. With a dusting of powder he graced his newly washed face, with a daub of pomade, his hair. Crunched up toast like charcoal from having been toasted upon the flame, with marmalade over the burn.8.30: he rode into the fields with the local officials and everyone else in the village going along for fun. Followed by an orderly holding an umbrella over his head to shield him from the glare, he measured the fields and checked to make sure his yield estimate matched the headman's statement. Farms were growing less than ten maunds an acre of rice or wheat, and at two rupees a maund, every single man in a village, sometimes, was in debt to the bania.

(Nobody knew that Jemuhhai himself was noosed, of course, that long ago in the little town of Piphit in Gujarat, moneylenders had sniffed out in him a winning combination of ambition and poverty … that they still sat waiting cross-legged on a soiled mat in the market, snapping their toes, cracking their knuckles in anticipation of repayment….) 2.00: after lunch, the judge sat at his desk under a tree to try cases, usually in a cross mood, for he disliked the informality, hated the splotch of leaf shadow on him imparting an untidy mongrel look. Also, there was a worse aspect of contamination and corruption; he heard cases in Hindi, but they were recorded in Urdu by the stenographer and translated by the judge into a second record in English, although his own command of Hindi and Urdu was tenuous; the witnesses who couldn't read at all put their thumbprints at the bottom of "Read Over and Acknowledged Correct", as instructed.

Nobody could be sure how much of the truth had fallen between languages, between languages and illiteracy; the clarity that justice demanded was nonexistent. Still, despite the leaf shadow and language confusion, he acquired a fearsome reputation for his speech that seemed to belong to no language at all, and for his face like a mask that conveyed something beyond human fallibility. The expression and manner honed here would carry him, eventually, all the way to the high court in Lucknow where, annoyed by lawless pigeons shuttlecocking about those tall, shadowy halls, he would preside, white powdered wig over white powdered face, hammer in hand. His photograph, thus attired, thus annoyed, was still up on the wall, in a parade of history glorifying the progress of Indian law and order.4:30: tea had to be perfect, drop scones made in the frying pan. He would embark on them with forehead wrinkled, as if angrily mulling over something important, and then, as it would into his retirement, the draw of the sweet took over, and his stern workface would hatch an expression of tranquillity. 5:30: out he went into the countryside with his fishing rod or gun. The countryside was full of game; lariats of migratory birds lassoed the sky in October; quail and partridge with lines of babies strung out behind whirred by like nursery toys that emit sound with movement; pheasant - fat foolish creatures, made to be shot - went scurrying, through the bushes. The thunder of gunshot rolled away, the leaves shivered, and he experienced the profound silence that could come only after violence. One thing was always missing, though, the proof of the pudding, the prize of the action, the manliness in manhood, the partridge for the pot, because he returned with - Nothing! He was a terrible shot.8:00: the cook saved his reputation, cooked a chicken, brought it forth, proclaimed it "roast bastard", just as in the Englishman's favourite joke book of natives using incorrect English.

But sometimes, eating that roast bustard, the judge felt the joke might also be on him, and he called for another rum, took a big gulp, and kept eating feeling as if he were eating himself, since he, too, was (was he?) part of the fun.... 9:00: sipping Ovaltine, he filled out the registers with the day's gleanings. The Petromax lantern would be lit - what as noise it made - insects fording the black to dive - bomb him with soft flowers (moths), with iridescence (beetles). Lines, columns, and squares. He realized truth was best looked at in tiny aggregates,for many baby truths could yet add up to one big size unsavory lie. Last, in his diary also to be submitted to his superiors, he recorded the random observations of a cultured man, someone who was observant, schooled in literature as well as economics; and he made up bunting triumphs: two partridge.... one deer with thirty-inch horns....11:00 : he had a hot water bottle in winter, and, in all seasons, to the sound of the wind buffeting the trees and the cook's snoring, he fell asleep.

Q. Which is the odd one out:

Read the Following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The movement to expel the Austrians from Italy and unite Italy under a republican government had been gaining momentum while Garibaldi was away. There was a growing clamour, not just from Giuseppe Mazzini's republicans, but from moderates as well, for a General capable of leading Italy to independence. Even the King of Piedmont, for whom Garibaldi was still an outlaw under sentence of death, subscribed to an appeal for a sword for the returning hero. Meanwhile, the 'year of revolutions', 1848, had occurred in which Louis Philippe had been toppled from the French throne.

In Austria, an uprising triggered off insurrections in Venice and Milan, and the Austrian garrisons were forced out. The King of Piedmont. Charles Albert ordered his troops to occupy these cities. There had also been instruction in Sicily, causing the King Ferdinand II, to grant major constitutional freedoms in 1849, prompting both the Pope and Charles Albert to grant further concessions.Meanwhile, largely ignorant of these developments, Garibaldi was approaching Italy at a leisurely pace, arriving at Nice on 23June 1848 to a tumultuous reception. The hero declared himself willing to fight and lay down his life for Charles Albert, who he now regarded as a bastion of Italian nationalism.

Mazzini and the republicans were horrified, regarding this as outright betrayal: did it reflect Garibaldi's innate simplemindedness,his patriotism in the war against Austria, or was it part of a deal with the monarchy'? Charles Albert had pardoned Garibaldi, but to outward appearances he was still very wary of the General and the ltalian Legion he had amassed of 150 'brigands'.The two men met near Mantua, and the King appeared to dislike him instantly. He suggested that Garibaldi's men should join his army and that Garibaldi should go to Venice and captain a ship as a privateer against the Austrians. Garibaldi, meanwhile, met his former hero Mazzini for the first time, and again the encounter was frosty. Seemingly rebuffed on all sides. Garibaldi considered going to Sicily to fight King Ferdinand II of Naples, but changed his mind when the Milanese offered him the post of General - something they badly needed when Charles Albert's Piedmontese army was defeated at Custoza by the Austrians. With around 1,000 men, Garibaldi marched into the mountains at Varese, commenting bitterly: 'The King of Sardinia may have a crown that he holds on to by dint of misdeeds and cowardice, but my comrades and I do not wish to hold on to our lives by shameful actions'.

The King of Piedmont offered an armistice to the Austrians and all the gains in northern Italy were lost again. Garibaldi returned to Nice and then across to Genoa, where he learned that, in September 1848, Ferdinand II had bombed Messina as a prelude to invasion - an atrocity which caused him to be dubbed 'King Bomba'. Reaching Livorno he was diverted yet again and set off across the Italian peninsula with 350 men to come to Venice's assistance, but on the way, in Bologna, he learned that the Pope had taken refuge with King Bomba. Garibaldi promptly altered course southwards towards Rome where he was greeted once again as a hero. Rome proclaimed itself a Republic. Garibaldi's Legion had swollen to nearly 1,300 men, and the Grand Duke of Tuscany fled Florence before the advancing republican force.

However, the Austrians marched southwards to place the Grand Duke of Tuscany back on his throne. Prince Louis Napoleon of France -despatched an army of 7,000 men under General Charles Oudinot to the port of Civitavecchia to seize the city. Garibaldi was appointed as a General to defend Rome.The republicans had around 9,000 men, and Garibaldi was given control of more than 4,000 to defend the Janiculum Hill, which was crucial to the defence of Rome, as it commanded the city over the Tiber. Some 5,000 well-equipped French troops arrived on 30 April 1849 at Porta Cavallegeri in the old walls of Rome, but failed to get through, and were attacked from behind by Garibaldi,who led a baton charge and was grazed by a bullet slightly on his side. The French lost 500 dead and wounded, along with some 350 prisoners, to the Italians, 200 dead and wounded. It was a famous victory, wildly celebrated by the Romans into the night,and the French signed a tactical truce.However, other armies were on the march: Bomba's 12,500- strong Neapolitan army was approaching from the south, while the Austrians had attacked Bologna in the north. Garibaldi took a force out of Rome and engaged in a flanking movement across the Neapolitan army's rear at Castelli Romani; the Neapolitans attacked and were driven off, leaving 50 dead. Garibaldi accompanied the Roman General, Piero Roselli, in an attack on the retreating Neapolitan army. Foolishly leading a patrol of his men right out infront of his forces, he tried to stop a group of his cavalry reheating and fell under their horses, with the enemy clashing at him with their sabres. He was rescued by his legionnaires, narrowly having avoided being killed, but Roselli had missed the chance to encircle the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi boldly wanted to carry the fight down into theKingdom of Naples, but Mazzini, who by now was effectively in charge of Rome, ordered him back to the capital to face the danger of Austrian attack from the north. In fact, it was the French who arrived on the outskirts of Rome first, with an army now reinforced by 30,000.

Mazzini realized that Rome could not resist and ordered a symbolic stand within the city itself, rather than surrender, for the purposes of international propaganda and to keep the struggle alive, whatever the cost. On 3 June the French arrived in force and seized the strategic country house, 'Villa Pamphili. Garibaldi rallied his forces and fought feverishly to retake the villa up narrow and steep city streets, capturing it, then losing it again. By the end of the day, the sides had 1,000 dead between them. Garibaldi once again had been in the thick of the fray, giving orders to his troops and fighting, it was said, like a lion. Although beaten off for the moment, the French imposed a siege in the morning, starving the city of provisions and bombarding its beautiful centre. On 30 June the French attacked again in force, while Garibaldi, at the head of his troops, fought back ferociously. But there was no prospect of holding the French off indefinitely, and Garibaldi decided to take his men out of the city to continue resistance inthe mountains. Mazzini fled to Britain while Garibaldi remained to fight for the cause. He had just 4,000 men, divided into two legions, and faced some 17,000 Austrians and Tuscans in the north, 30,000 Neapolitans and Spanish in the south, and 40,000 French in the west. He was being directly pursued by 8,000 French and was approaching Neapolitan and Spanish divisions of some 18,000 men. He stood no chance whatever. The rugged hill country wasideal, however, for his style of irregular guerrilla warfare, and he rnanoeuvred skilfully, marching and counter-marching in different directions, confounding his pursuers before finally aiming for Arezzo in the north. But his men were deserting in droves and local people were hostile to his army: he was soon reduced to 1500 men who struggled across the high mountain passes to San Marino where he found temporary refuge. The Austrians, now approaching, demanded that he go into exile in America. He was determined to fight on and urged the ill and pregnant Anita, his wife, to stay behind in San Marino, but she would not hear of it. The pair set off with 200 loyal soldiers along the mountain tracks to the Adriatic coast, from where Garibaldi intended to embark for Venice which was still valiantly holding out against the Austrians. They embarked aboard 13 fishing boats and managed to sail to within 50 miles of the Venetian lagoon before being spotted by an Austrian flotilla and fired upon. Only two of Garibaldi's boats escaped.

He carried Anita through the shallows to a beach and they moved further inland. The ailing Anita was placed in a cart and they reached a farmhouse, where she died. Her husband broke down into inconsolable wailing and she was buried in a shallow grave near the farmhouse, but was transferred to a churchyard a few days later. Garibaldi had no time to lose; he and his faithful companion Leggero escaped across the Po towards Ravenna.At last Garibaldi was persuaded to abandon his insane attempts to reach Venice by sea and to return along less guarded routes on the perilous mountain paths across the Apennines towards the western coast of Italy. He visited his family in Nice for an emotional reunion with his mother and his three children but lacked the courage to tell them what had happened to their mother.

Q. Find the correct statement:

Read the Following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The movement to expel the Austrians from Italy and unite Italy under a republican government had been gaining momentum while Garibaldi was away. There was a growing clamour, not just from Giuseppe Mazzini's republicans, but from moderates as well, for a General capable of leading Italy to independence. Even the King of Piedmont, for whom Garibaldi was still an outlaw under sentence of death, subscribed to an appeal for a sword for the returning hero. Meanwhile, the 'year of revolutions', 1848, had occurred in which Louis Philippe had been toppled from the French throne.

In Austria, an uprising triggered off insurrections in Venice and Milan, and the Austrian garrisons were forced out. The King of Piedmont. Charles Albert ordered his troops to occupy these cities. There had also been instruction in Sicily, causing the King Ferdinand II, to grant major constitutional freedoms in 1849, prompting both the Pope and Charles Albert to grant further concessions.Meanwhile, largely ignorant of these developments, Garibaldi was approaching Italy at a leisurely pace, arriving at Nice on 23June 1848 to a tumultuous reception. The hero declared himself willing to fight and lay down his life for Charles Albert, who he now regarded as a bastion of Italian nationalism.

Mazzini and the republicans were horrified, regarding this as outright betrayal: did it reflect Garibaldi's innate simplemindedness,his patriotism in the war against Austria, or was it part of a deal with the monarchy'? Charles Albert had pardoned Garibaldi, but to outward appearances he was still very wary of the General and the ltalian Legion he had amassed of 150 'brigands'.The two men met near Mantua, and the King appeared to dislike him instantly. He suggested that Garibaldi's men should join his army and that Garibaldi should go to Venice and captain a ship as a privateer against the Austrians. Garibaldi, meanwhile, met his former hero Mazzini for the first time, and again the encounter was frosty. Seemingly rebuffed on all sides. Garibaldi considered going to Sicily to fight King Ferdinand II of Naples, but changed his mind when the Milanese offered him the post of General - something they badly needed when Charles Albert's Piedmontese army was defeated at Custoza by the Austrians. With around 1,000 men, Garibaldi marched into the mountains at Varese, commenting bitterly: 'The King of Sardinia may have a crown that he holds on to by dint of misdeeds and cowardice, but my comrades and I do not wish to hold on to our lives by shameful actions'.

The King of Piedmont offered an armistice to the Austrians and all the gains in northern Italy were lost again. Garibaldi returned to Nice and then across to Genoa, where he learned that, in September 1848, Ferdinand II had bombed Messina as a prelude to invasion - an atrocity which caused him to be dubbed 'King Bomba'. Reaching Livorno he was diverted yet again and set off across the Italian peninsula with 350 men to come to Venice's assistance, but on the way, in Bologna, he learned that the Pope had taken refuge with King Bomba. Garibaldi promptly altered course southwards towards Rome where he was greeted once again as a hero. Rome proclaimed itself a Republic. Garibaldi's Legion had swollen to nearly 1,300 men, and the Grand Duke of Tuscany fled Florence before the advancing republican force.

However, the Austrians marched southwards to place the Grand Duke of Tuscany back on his throne. Prince Louis Napoleon of France -despatched an army of 7,000 men under General Charles Oudinot to the port of Civitavecchia to seize the city. Garibaldi was appointed as a General to defend Rome.The republicans had around 9,000 men, and Garibaldi was given control of more than 4,000 to defend the Janiculum Hill, which was crucial to the defence of Rome, as it commanded the city over the Tiber. Some 5,000 well-equipped French troops arrived on 30 April 1849 at Porta Cavallegeri in the old walls of Rome, but failed to get through, and were attacked from behind by Garibaldi,who led a baton charge and was grazed by a bullet slightly on his side. The French lost 500 dead and wounded, along with some 350 prisoners, to the Italians, 200 dead and wounded. It was a famous victory, wildly celebrated by the Romans into the night,and the French signed a tactical truce.However, other armies were on the march: Bomba's 12,500- strong Neapolitan army was approaching from the south, while the Austrians had attacked Bologna in the north. Garibaldi took a force out of Rome and engaged in a flanking movement across the Neapolitan army's rear at Castelli Romani; the Neapolitans attacked and were driven off, leaving 50 dead. Garibaldi accompanied the Roman General, Piero Roselli, in an attack on the retreating Neapolitan army. Foolishly leading a patrol of his men right out infront of his forces, he tried to stop a group of his cavalry reheating and fell under their horses, with the enemy clashing at him with their sabres. He was rescued by his legionnaires, narrowly having avoided being killed, but Roselli had missed the chance to encircle the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi boldly wanted to carry the fight down into theKingdom of Naples, but Mazzini, who by now was effectively in charge of Rome, ordered him back to the capital to face the danger of Austrian attack from the north. In fact, it was the French who arrived on the outskirts of Rome first, with an army now reinforced by 30,000.

Mazzini realized that Rome could not resist and ordered a symbolic stand within the city itself, rather than surrender, for the purposes of international propaganda and to keep the struggle alive, whatever the cost. On 3 June the French arrived in force and seized the strategic country house, 'Villa Pamphili. Garibaldi rallied his forces and fought feverishly to retake the villa up narrow and steep city streets, capturing it, then losing it again. By the end of the day, the sides had 1,000 dead between them. Garibaldi once again had been in the thick of the fray, giving orders to his troops and fighting, it was said, like a lion. Although beaten off for the moment, the French imposed a siege in the morning, starving the city of provisions and bombarding its beautiful centre. On 30 June the French attacked again in force, while Garibaldi, at the head of his troops, fought back ferociously. But there was no prospect of holding the French off indefinitely, and Garibaldi decided to take his men out of the city to continue resistance inthe mountains. Mazzini fled to Britain while Garibaldi remained to fight for the cause. He had just 4,000 men, divided into two legions, and faced some 17,000 Austrians and Tuscans in the north, 30,000 Neapolitans and Spanish in the south, and 40,000 French in the west. He was being directly pursued by 8,000 French and was approaching Neapolitan and Spanish divisions of some 18,000 men. He stood no chance whatever. The rugged hill country wasideal, however, for his style of irregular guerrilla warfare, and he rnanoeuvred skilfully, marching and counter-marching in different directions, confounding his pursuers before finally aiming for Arezzo in the north. But his men were deserting in droves and local people were hostile to his army: he was soon reduced to 1500 men who struggled across the high mountain passes to San Marino where he found temporary refuge. The Austrians, now approaching, demanded that he go into exile in America. He was determined to fight on and urged the ill and pregnant Anita, his wife, to stay behind in San Marino, but she would not hear of it. The pair set off with 200 loyal soldiers along the mountain tracks to the Adriatic coast, from where Garibaldi intended to embark for Venice which was still valiantly holding out against the Austrians. They embarked aboard 13 fishing boats and managed to sail to within 50 miles of the Venetian lagoon before being spotted by an Austrian flotilla and fired upon. Only two of Garibaldi's boats escaped.

He carried Anita through the shallows to a beach and they moved further inland. The ailing Anita was placed in a cart and they reached a farmhouse, where she died. Her husband broke down into inconsolable wailing and she was buried in a shallow grave near the farmhouse, but was transferred to a churchyard a few days later. Garibaldi had no time to lose; he and his faithful companion Leggero escaped across the Po towards Ravenna.At last Garibaldi was persuaded to abandon his insane attempts to reach Venice by sea and to return along less guarded routes on the perilous mountain paths across the Apennines towards the western coast of Italy. He visited his family in Nice for an emotional reunion with his mother and his three children but lacked the courage to tell them what had happened to their mother.

Q. Which of the following statements can be deduced from the passage?

Read the Following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The movement to expel the Austrians from Italy and unite Italy under a republican government had been gaining momentum while Garibaldi was away. There was a growing clamour, not just from Giuseppe Mazzini's republicans, but from moderates as well, for a General capable of leading Italy to independence. Even the King of Piedmont, for whom Garibaldi was still an outlaw under sentence of death, subscribed to an appeal for a sword for the returning hero. Meanwhile, the 'year of revolutions', 1848, had occurred in which Louis Philippe had been toppled from the French throne.

In Austria, an uprising triggered off insurrections in Venice and Milan, and the Austrian garrisons were forced out. The King of Piedmont. Charles Albert ordered his troops to occupy these cities. There had also been instruction in Sicily, causing the King Ferdinand II, to grant major constitutional freedoms in 1849, prompting both the Pope and Charles Albert to grant further concessions.Meanwhile, largely ignorant of these developments, Garibaldi was approaching Italy at a leisurely pace, arriving at Nice on 23June 1848 to a tumultuous reception. The hero declared himself willing to fight and lay down his life for Charles Albert, who he now regarded as a bastion of Italian nationalism.

Mazzini and the republicans were horrified, regarding this as outright betrayal: did it reflect Garibaldi's innate simple mindedness, his patriotism in the war against Austria, or was it part of a deal with the monarchy'? Charles Albert had pardoned Garibaldi, but to outward appearances he was still very wary of the General and the ltalian Legion he had amassed of 150 'brigands'.The two men met near Mantua, and the King appeared to dislike him instantly. He suggested that Garibaldi's men should join his army and that Garibaldi should go to Venice and captain a ship as a privateer against the Austrians. Garibaldi, meanwhile, met his former hero Mazzini for the first time, and again the encounter was frosty. Seemingly rebuffed on all sides. Garibaldi considered going to Sicily to fight King Ferdinand II of Naples, but changed his mind when the Milanese offered him the post of General - something they badly needed when Charles Albert's Piedmontese army was defeated at Custoza by the Austrians. With around 1,000 men, Garibaldi marched into the mountains at Varese, commenting bitterly: 'The King of Sardinia may have a crown that he holds on to by dint of misdeeds and cowardice, but my comrades and I do not wish to hold on to our lives by shameful actions'.

The King of Piedmont offered an armistice to the Austrians and all the gains in northern Italy were lost again. Garibaldi returned to Nice and then across to Genoa, where he learned that, in September 1848, Ferdinand II had bombed Messina as a prelude to invasion - an atrocity which caused him to be dubbed 'King Bomba'. Reaching Livorno he was diverted yet again and set off across the Italian peninsula with 350 men to come to Venice's assistance, but on the way, in Bologna, he learned that the Pope had taken refuge with King Bomba. Garibaldi promptly altered course southwards towards Rome where he was greeted once again as a hero. Rome proclaimed itself a Republic. Garibaldi's Legion had swollen to nearly 1,300 men, and the Grand Duke of Tuscany fled Florence before the advancing republican force.

However, the Austrians marched southwards to place the Grand Duke of Tuscany back on his throne. Prince Louis Napoleon of France -despatched an army of 7,000 men under General Charles Oudinot to the port of Civitavecchia to seize the city. Garibaldi was appointed as a General to defend Rome.The republicans had around 9,000 men, and Garibaldi was given control of more than 4,000 to defend the Janiculum Hill, which was crucial to the defence of Rome, as it commanded the city over the Tiber. Some 5,000 well-equipped French troops arrived on 30 April 1849 at Porta Cavallegeri in the old walls of Rome, but failed to get through, and were attacked from behind by Garibaldi,who led a baton charge and was grazed by a bullet slightly on his side. The French lost 500 dead and wounded, along with some 350 prisoners, to the Italians, 200 dead and wounded. It was a famous victory, wildly celebrated by the Romans into the night,and the French signed a tactical truce.However, other armies were on the march: Bomba's 12,500- strong Neapolitan army was approaching from the south, while the Austrians had attacked Bologna in the north. Garibaldi took a force out of Rome and engaged in a flanking movement across the Neapolitan army's rear at Castelli Romani; the Neapolitans attacked and were driven off, leaving 50 dead. Garibaldi accompanied the Roman General, Piero Roselli, in an attack on the retreating Neapolitan army. Foolishly leading a patrol of his men right out infront of his forces, he tried to stop a group of his cavalry reheating and fell under their horses, with the enemy clashing at him with their sabres. He was rescued by his legionnaires, narrowly having avoided being killed, but Roselli had missed the chance to encircle the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi boldly wanted to carry the fight down into theKingdom of Naples, but Mazzini, who by now was effectively in charge of Rome, ordered him back to the capital to face the danger of Austrian attack from the north. In fact, it was the French who arrived on the outskirts of Rome first, with an army now reinforced by 30,000.

Mazzini realized that Rome could not resist and ordered a symbolic stand within the city itself, rather than surrender, for the purposes of international propaganda and to keep the struggle alive, whatever the cost. On 3 June the French arrived in force and seized the strategic country house, 'Villa Pamphili. Garibaldi rallied his forces and fought feverishly to retake the villa up narrow and steep city streets, capturing it, then losing it again. By the end of the day, the sides had 1,000 dead between them. Garibaldi once again had been in the thick of the fray, giving orders to his troops and fighting, it was said, like a lion. Although beaten off for the moment, the French imposed a siege in the morning, starving the city of provisions and bombarding its beautiful centre. On 30 June the French attacked again in force, while Garibaldi, at the head of his troops, fought back ferociously. But there was no prospect of holding the French off indefinitely, and Garibaldi decided to take his men out of the city to continue resistance inthe mountains. Mazzini fled to Britain while Garibaldi remained to fight for the cause. He had just 4,000 men, divided into two legions, and faced some 17,000 Austrians and Tuscans in the north, 30,000 Neapolitans and Spanish in the south, and 40,000 French in the west. He was being directly pursued by 8,000 French and was approaching Neapolitan and Spanish divisions of some 18,000 men. He stood no chance whatever. The rugged hill country wasideal, however, for his style of irregular guerrilla warfare, and he rnanoeuvred skilfully, marching and counter-marching in different directions, confounding his pursuers before finally aiming for Arezzo in the north. But his men were deserting in droves and local people were hostile to his army: he was soon reduced to 1500 men who struggled across the high mountain passes to San Marino where he found temporary refuge. The Austrians, now approaching, demanded that he go into exile in America. He was determined to fight on and urged the ill and pregnant Anita, his wife, to stay behind in San Marino, but she would not hear of it. The pair set off with 200 loyal soldiers along the mountain tracks to the Adriatic coast, from where Garibaldi intended to embark for Venice which was still valiantly holding out against the Austrians. They embarked aboard 13 fishing boats and managed to sail to within 50 miles of the Venetian lagoon before being spotted by an Austrian flotilla and fired upon. Only two of Garibaldi's boats escaped.

He carried Anita through the shallows to a beach and they moved further inland. The ailing Anita was placed in a cart and they reached a farmhouse, where she died. Her husband broke down into inconsolable wailing and she was buried in a shallow grave near the farmhouse, but was transferred to a churchyard a few days later. Garibaldi had no time to lose; he and his faithful companion Leggero escaped across the Po towards Ravenna.At last Garibaldi was persuaded to abandon his insane attempts to reach Venice by sea and to return along less guarded routes on the perilous mountain paths across the Apennines towards the western coast of Italy. He visited his family in Nice for an emotional reunion with his mother and his three children but lacked the courage to tell them what had happened to their mother.

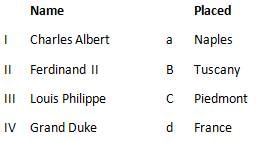

Q. Match the Following:

Read the Following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

The movement to expel the Austrians from Italy and unite Italy under a republican government had been gaining momentum while Garibaldi was away. There was a growing clamour, not just from Giuseppe Mazzini's republicans, but from moderates as well, for a General capable of leading Italy to independence. Even the King of Piedmont, for whom Garibaldi was still an outlaw under sentence of death, subscribed to an appeal for a sword for the returning hero. Meanwhile, the 'year of revolutions', 1848, had occurred in which Louis Philippe had been toppled from the French throne.

In Austria, an uprising triggered off insurrections in Venice and Milan, and the Austrian garrisons were forced out. The King of Piedmont. Charles Albert ordered his troops to occupy these cities. There had also been instruction in Sicily, causing the King Ferdinand II, to grant major constitutional freedoms in 1849, prompting both the Pope and Charles Albert to grant further concessions.Meanwhile, largely ignorant of these developments, Garibaldi was approaching Italy at a leisurely pace, arriving at Nice on 23June 1848 to a tumultuous reception. The hero declared himself willing to fight and lay down his life for Charles Albert, who he now regarded as a bastion of Italian nationalism.

Mazzini and the republicans were horrified, regarding this as outright betrayal: did it reflect Garibaldi's innate simplemindedness,his patriotism in the war against Austria, or was it part of a deal with the monarchy'? Charles Albert had pardoned Garibaldi, but to outward appearances he was still very wary of the General and the ltalian Legion he had amassed of 150 'brigands'.The two men met near Mantua, and the King appeared to dislike him instantly. He suggested that Garibaldi's men should join his army and that Garibaldi should go to Venice and captain a ship as a privateer against the Austrians. Garibaldi, meanwhile, met his former hero Mazzini for the first time, and again the encounter was frosty. Seemingly rebuffed on all sides. Garibaldi considered going to Sicily to fight King Ferdinand II of Naples, but changed his mind when the Milanese offered him the post of General - something they badly needed when Charles Albert's Piedmontese army was defeated at Custoza by the Austrians. With around 1,000 men, Garibaldi marched into the mountains at Varese, commenting bitterly: 'The King of Sardinia may have a crown that he holds on to by dint of misdeeds and cowardice, but my comrades and I do not wish to hold on to our lives by shameful actions'.

The King of Piedmont offered an armistice to the Austrians and all the gains in northern Italy were lost again. Garibaldi returned to Nice and then across to Genoa, where he learned that, in September 1848, Ferdinand II had bombed Messina as a prelude to invasion - an atrocity which caused him to be dubbed 'King Bomba'. Reaching Livorno he was diverted yet again and set off across the Italian peninsula with 350 men to come to Venice's assistance, but on the way, in Bologna, he learned that the Pope had taken refuge with King Bomba. Garibaldi promptly altered course southwards towards Rome where he was greeted once again as a hero. Rome proclaimed itself a Republic. Garibaldi's Legion had swollen to nearly 1,300 men, and the Grand Duke of Tuscany fled Florence before the advancing republican force.

However, the Austrians marched southwards to place the Grand Duke of Tuscany back on his throne. Prince Louis Napoleon of France -despatched an army of 7,000 men under General Charles Oudinot to the port of Civitavecchia to seize the city. Garibaldi was appointed as a General to defend Rome.The republicans had around 9,000 men, and Garibaldi was given control of more than 4,000 to defend the Janiculum Hill, which was crucial to the defence of Rome, as it commanded the city over the Tiber. Some 5,000 well-equipped French troops arrived on 30 April 1849 at Porta Cavallegeri in the old walls of Rome, but failed to get through, and were attacked from behind by Garibaldi,who led a baton charge and was grazed by a bullet slightly on his side. The French lost 500 dead and wounded, along with some 350 prisoners, to the Italians, 200 dead and wounded. It was a famous victory, wildly celebrated by the Romans into the night,and the French signed a tactical truce.However, other armies were on the march: Bomba's 12,500- strong Neapolitan army was approaching from the south, while the Austrians had attacked Bologna in the north. Garibaldi took a force out of Rome and engaged in a flanking movement across the Neapolitan army's rear at Castelli Romani; the Neapolitans attacked and were driven off, leaving 50 dead. Garibaldi accompanied the Roman General, Piero Roselli, in an attack on the retreating Neapolitan army. Foolishly leading a patrol of his men right out infront of his forces, he tried to stop a group of his cavalry reheating and fell under their horses, with the enemy clashing at him with their sabres. He was rescued by his legionnaires, narrowly having avoided being killed, but Roselli had missed the chance to encircle the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi boldly wanted to carry the fight down into theKingdom of Naples, but Mazzini, who by now was effectively in charge of Rome, ordered him back to the capital to face the danger of Austrian attack from the north. In fact, it was the French who arrived on the outskirts of Rome first, with an army now reinforced by 30,000.