XAT Mock Test - 4 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test Mock Test Series for XAT - XAT Mock Test - 4 (New Pattern)

In each of the questions below, five sentences, labeled A, B, C, D and E, are given. They need to be arranged in a logical order to form a coherent paragraph/passage. From the given options, choose the most appropriate option.

A. Archaeologists have found evidence of Mesopotamian beer-making dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.

B. Along with inventing writing, the wheel, the plow, law codes and literature, the Sumerians are also remembered as some of history's original brewers.

C. The brewing techniques they used are still a mystery, but their preferred ale seems to have been a barley-based concoction so thick that it had to be sipped through a special kind of filtration straw.

D. The Sumerians prized their beer for its nutrient-rich ingredients and hailed it as the key to a "joyful heart and a contented liver."

E. There was even a Sumerian goddess of brewing called "Ninkasi," who is celebrated in a famous hymn as the "one who waters the malt set on the ground."

In each of the question below, a sentence is given with a portion underlined. Choose the best replacement (if needed) for the underlined portion to make the sentence meaningful and grammatically correct

The landlady said she would move heaven and earth, for so good a gentleman; and then consented to give me her sleeping-room on the ground-floor, at some trifle or other, - I forget what.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

There is an Indian savagery, a savagery peculiar to the Indian blood, in the manner in which the Americans strive after gold: and the breathless hurry of their work - the characteristic vice of the New World - already begins to infect old Europe, and makes it savage also, spreading over it a strange lack of intellectuality.

One is now ashamed of repose: even long reflection almost causes remorse of conscience. Thinking is done with a stop-watch, as dining is done with the eyes fixed on the financial newspaper; we live like men who are continually "afraid of letting opportunities slip." "Better do anything whatever, than nothing" - this principle also is a noose with which all culture and all higher taste may be strangled. And just as all form obviously disappears in this hurry of workers, so the sense for form itself, the ear and the eye for the melody of movement, also disappear.

For life in the hunt for gain continually compels a person to consume his intellect, even to exhaustion, in constant dissimulation, overreaching, or forestalling: the real virtue nowadays is to do something in a shorter time than another person. And so there are only rare hours of sincere intercourse permitted: in them, however, people are tired, and would not only like "to let themselves go," but to stretch their legs out wide in awkward style.

The way people write their letters nowadays is quite in keeping with the age; their style and spirit will always be the true "sign of the times." If there be still enjoyment in society and in art, it is enjoyment such as over-worked slaves provide for themselves. Oh, this moderation in "joy" of our cultured and uncultured classes! Oh, this increasing suspiciousness of all enjoyment! Work is winning over more and more the good conscience to its side: the desire for enjoyment already calls itself "need of recreation," and even begins to be ashamed of itself.

"One owes it to one's health," people say, when they are caught at a picnic. Indeed, it might soon go so far that one could not yield to the desire for the vita contemplative, (that is to say, excursions with thoughts and friends), without self-contempt and a bad conscience. Well! Formerly it was the very reverse: it was "action" that suffered from a bad conscience. A man of good family concealed his work when need compelled him to labour. The slave laboured under the weight of the feeling that he did something contemptible: the "doing" itself was something contemptible. "Only in otium and bellum is there nobility and honour:" so rang the voice of ancient prejudice!

Which of the following is the central theme explored in the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

There is an Indian savagery, a savagery peculiar to the Indian blood, in the manner in which the Americans strive after gold: and the breathless hurry of their work - the characteristic vice of the New World - already begins to infect old Europe, and makes it savage also, spreading over it a strange lack of intellectuality.

One is now ashamed of repose: even long reflection almost causes remorse of conscience. Thinking is done with a stop-watch, as dining is done with the eyes fixed on the financial newspaper; we live like men who are continually "afraid of letting opportunities slip." "Better do anything whatever, than nothing" - this principle also is a noose with which all culture and all higher taste may be strangled. And just as all form obviously disappears in this hurry of workers, so the sense for form itself, the ear and the eye for the melody of movement, also disappear.

For life in the hunt for gain continually compels a person to consume his intellect, even to exhaustion, in constant dissimulation, overreaching, or forestalling: the real virtue nowadays is to do something in a shorter time than another person. And so there are only rare hours of sincere intercourse permitted: in them, however, people are tired, and would not only like "to let themselves go," but to stretch their legs out wide in awkward style.

The way people write their letters nowadays is quite in keeping with the age; their style and spirit will always be the true "sign of the times." If there be still enjoyment in society and in art, it is enjoyment such as over-worked slaves provide for themselves. Oh, this moderation in "joy" of our cultured and uncultured classes! Oh, this increasing suspiciousness of all enjoyment! Work is winning over more and more the good conscience to its side: the desire for enjoyment already calls itself "need of recreation," and even begins to be ashamed of itself.

"One owes it to one's health," people say, when they are caught at a picnic. Indeed, it might soon go so far that one could not yield to the desire for the vita contemplative, (that is to say, excursions with thoughts and friends), without self-contempt and a bad conscience. Well!

Formerly it was the very reverse: it was "action" that suffered from a bad conscience. A man of good family concealed his work when need compelled him to labour. The slave laboured under the weight of the feeling that he did something contemptible: the "doing" itself was something contemptible. "Only in otium and bellum is there nobility and honour:" so rang the voice of ancient prejudice!

According to the author, what is the difference in the past and present times, with regard to action and inaction?

Directions : Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

There is an Indian savagery, a savagery peculiar to the Indian blood, in the manner in which the Americans strive after gold: and the breathless hurry of their work - the characteristic vice of the New World - already begins to infect old Europe, and makes it savage also, spreading over it a strange lack of intellectuality.

One is now ashamed of repose: even long reflection almost causes remorse of conscience. Thinking is done with a stop-watch, as dining is done with the eyes fixed on the financial newspaper; we live like men who are continually "afraid of letting opportunities slip." "Better do anything whatever, than nothing" - this principle also is a noose with which all culture and all higher taste may be strangled. And just as all form obviously disappears in this hurry of workers, so the sense for form itself, the ear and the eye for the melody of movement, also disappear.

For life in the hunt for gain continually compels a person to consume his intellect, even to exhaustion, in constant dissimulation, overreaching, or forestalling: the real virtue nowadays is to do something in a shorter time than another person. And so there are only rare hours of sincere intercourse permitted: in them, however, people are tired, and would not only like "to let themselves go," but to stretch their legs out wide in awkward style.

The way people write their letters nowadays is quite in keeping with the age; their style and spirit will always be the true "sign of the times." If there be still enjoyment in society and in art, it is enjoyment such as over-worked slaves provide for themselves. Oh, this moderation in "joy" of our cultured and uncultured classes! Oh, this increasing suspiciousness of all enjoyment! Work is winning over more and more the good conscience to its side: the desire for enjoyment already calls itself "need of recreation," and even begins to be ashamed of itself.

"One owes it to one's health," people say, when they are caught at a picnic. Indeed, it might soon go so far that one could not yield to the desire for the vita contemplative, (that is to say, excursions with thoughts and friends), without self-contempt and a bad conscience. Well! Formerly it was the very reverse: it was "action" that suffered from a bad conscience. A man of good family concealed his work when need compelled him to labour. The slave laboured under the weight of the feeling that he did something contemptible: the "doing" itself was something contemptible. "Only in otium and bellum is there nobility and honour:" so rang the voice of ancient prejudice!

Which of the following would be the most suitable title of the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When Chesterton wrote his introductions to the Everyman Edition of Dickens's works, it seemed quite natural to him to credit Dickens with his own highly individual brand of medievalism, and more recently a Marxist writer, Mr. T. A. Jackson, has made spirited efforts to turn Dickens into a blood-thirsty revolutionary. The Marxist claims him as 'almost' a Marxist, the Catholic claims him as 'almost' a Catholic, and both claim him as a champion of the proletariat (or 'the poor', as Chesterton would have put it). On the other hand, Nadezhda Krupskaya, in her little book on Lenin, relates that towards the end of his life Lenin went to see a dramatized version of The Cricket on the Hearth, and found Dickens's 'middle-class sentimentality' so intolerable that he walked out in the middle of a scene.

Taking 'middle-class' to mean what Krupskaya might be expected to mean by it, this was probably a truer judgement than those of Chesterton and Jackson. But it is worth noticing that the dislike of Dickens implied in this remark is something unusual. Plenty of people have found him unreadable, but very few seem to have felt any hostility towards the general spirit of his work.

Some years later Mr. Bechhofer Roberts published a full-length attack on Dickens in the form of a novel (This Side Idolatry), but it was a merely personal attack, concerned for the most part with Dickens's treatment of his wife. It dealt with incidents which not one in a thousand of Dickens's readers would ever hear about, and which no more invalidates his work than the second-best bed invalidates Hamlet. All that the book really demonstrated was that a writer's literary personality has little or nothing to do with his private character. It is quite possible that in private life Dickens was just the kind of insensitive egoist that Mr. Bechhofer Roberts makes him appear. But in his published work there is implied a personality quite different from this, a personality which has won him far more friends than enemies.

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself. In its attitude towards Dickens the English public has always been a little like the elephant which feels a blow with a walking-stick as a delightful tickling.

Before I was ten years old I was having Dickens ladled down my throat by schoolmasters in whom even at that age I could see a strong resemblance to Mr. Creakle, and one knows without needing to be told that lawyers delight in Sergeant Buzfuz and that Little Dorrit is a favourite in the Home Office. Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody. Naturally this makes one wonder whether after all there was something unreal in his attack upon society. Where exactly does he stand, socially, morally, and politically? As usual, one can define his position more easily if one starts by deciding what he was not.

The passage is most likely to be an excerpt from which of the following?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When Chesterton wrote his introductions to the Everyman Edition of Dickens's works, it seemed quite natural to him to credit Dickens with his own highly individual brand of medievalism, and more recently a Marxist writer, Mr. T. A. Jackson, has made spirited efforts to turn Dickens into a blood-thirsty revolutionary. The Marxist claims him as 'almost' a Marxist, the Catholic claims him as 'almost' a Catholic, and both claim him as a champion of the proletariat (or 'the poor', as Chesterton would have put it). On the other hand, Nadezhda Krupskaya, in her little book on Lenin, relates that towards the end of his life Lenin went to see a dramatized version of The Cricket on the Hearth, and found Dickens's 'middle-class sentimentality' so intolerable that he walked out in the middle of a scene.

Taking 'middle-class' to mean what Krupskaya might be expected to mean by it, this was probably a truer judgement than those of Chesterton and Jackson. But it is worth noticing that the dislike of Dickens implied in this remark is something unusual. Plenty of people have found him unreadable, but very few seem to have felt any hostility towards the general spirit of his work.

Some years later Mr. Bechhofer Roberts published a full-length attack on Dickens in the form of a novel (This Side Idolatry), but it was a merely personal attack, concerned for the most part with Dickens's treatment of his wife. It dealt with incidents which not one in a thousand of Dickens's readers would ever hear about, and which no more invalidates his work than the second-best bed invalidates Hamlet. All that the book really demonstrated was that a writer's literary personality has little or nothing to do with his private character. It is quite possible that in private life Dickens was just the kind of insensitive egoist that Mr. Bechhofer Roberts makes him appear. But in his published work there is implied a personality quite different from this, a personality which has won him far more friends than enemies.

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself. In its attitude towards Dickens the English public has always been a little like the elephant which feels a blow with a walking-stick as a delightful tickling.

Before I was ten years old I was having Dickens ladled down my throat by schoolmasters in whom even at that age I could see a strong resemblance to Mr. Creakle, and one knows without needing to be told that lawyers delight in Sergeant Buzfuz and that Little Dorrit is a favourite in the Home Office. Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody. Naturally this makes one wonder whether after all there was something unreal in his attack upon society. Where exactly does he stand, socially, morally, and politically? As usual, one can define his position more easily if one starts by deciding what he was not.

It can be inferred from the passage that the author:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When Chesterton wrote his introductions to the Everyman Edition of Dickens's works, it seemed quite natural to him to credit Dickens with his own highly individual brand of medievalism, and more recently a Marxist writer, Mr. T. A. Jackson, has made spirited efforts to turn Dickens into a blood-thirsty revolutionary. The Marxist claims him as 'almost' a Marxist, the Catholic claims him as 'almost' a Catholic, and both claim him as a champion of the proletariat (or 'the poor', as Chesterton would have put it). On the other hand, Nadezhda Krupskaya, in her little book on Lenin, relates that towards the end of his life Lenin went to see a dramatized version of The Cricket on the Hearth, and found Dickens's 'middle-class sentimentality' so intolerable that he walked out in the middle of a scene.

Taking 'middle-class' to mean what Krupskaya might be expected to mean by it, this was probably a truer judgement than those of Chesterton and Jackson. But it is worth noticing that the dislike of Dickens implied in this remark is something unusual. Plenty of people have found him unreadable, but very few seem to have felt any hostility towards the general spirit of his work.

Some years later Mr. Bechhofer Roberts published a full-length attack on Dickens in the form of a novel (This Side Idolatry), but it was a merely personal attack, concerned for the most part with Dickens's treatment of his wife. It dealt with incidents which not one in a thousand of Dickens's readers would ever hear about, and which no more invalidates his work than the second-best bed invalidates Hamlet. All that the book really demonstrated was that a writer's literary personality has little or nothing to do with his private character. It is quite possible that in private life Dickens was just the kind of insensitive egoist that Mr. Bechhofer Roberts makes him appear. But in his published work there is implied a personality quite different from this, a personality which has won him far more friends than enemies.

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself. In its attitude towards Dickens the English public has always been a little like the elephant which feels a blow with a walking-stick as a delightful tickling.

Before I was ten years old I was having Dickens ladled down my throat by schoolmasters in whom even at that age I could see a strong resemblance to Mr. Creakle, and one knows without needing to be told that lawyers delight in Sergeant Buzfuz and that Little Dorrit is a favourite in the Home Office. Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody. Naturally this makes one wonder whether after all there was something unreal in his attack upon society. Where exactly does he stand, socially, morally, and politically? As usual, one can define his position more easily if one starts by deciding what he was not.

The primary purpose of the third paragraph is:

In each of these questions, one word is given in the question and five words given in the options. Find the word which is most nearly the same or opposite in meaning to the given word.

rancour

Pharmacists recently conducted a study with respect to the reasons their customers purchased eye drops to soothe eye dryness. Dry eyes were more frequently experienced by customers who wore contact lenses than by customers who did not wear contact lenses. The pharmacists concluded that wearing contact lenses, by itself, can cause contact wearers to have dry eyes.

Which one of the following statements, if true, most seriously undermines the pharmacists’ conclusion?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

If we look back at the English literature of the last ten years not so much at the literature as at the prevailing literary attitude, the thing that strikes us is that it has almost ceased to be aesthetic. Literature has been swamped by propaganda. I do not mean that all the books written during that period have been bad. But the characteristic writers of the time, people like Auden and Spender and MacNeice, have been didactic, political writers, aesthetically conscious, of course, but more interested in subject-matter than in technique.

This is all the more striking because it makes a very sharp and sudden contrast with the period immediately before it. The characteristic writers of the nineteen-twenties - T. S. Eliot, for instance, Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf - were writers who put the main emphasis on technique. They had their beliefs and prejudices, of course, but they were far more interested in technical innovations than in any moral or meaning or political implication that their work might contain. The best of them all, James Joyce, was a technician and very little else, about as near to being a 'pure' artist as a writer can be. Even D. H. Lawrence, though he was more of a 'writer with a purpose' than most of the others of his time, had not much of what we should now call social consciousness. And though I have narrowed this down to the nineteen-twenties, it had really been the same from about 1890 onwards. Throughout the whole of that period, the notion that form is more important than subject-matter, the notion of 'art for art's sake', had been taken for granted. There were writers who disagreed, of course - Bernard Shaw was one - but that was the prevailing outlook.

Now, how is one to account for this very sudden change of outlook? About the end of the nineteen-twenties you get a book like Edith Sitwell's book on Pope, with a completely frivolous emphasis on technique, treating literature as a sort of embroidery, almost as though words did not have meanings: and only a few years later you get a Marxist critic like Edward Upward asserting that books can be 'good' only when they are Marxist in tendency. In a sense both Edith Sitwell and Edward Upward were representative of their period. The question is why should their outlook be so different?

I think one has got to look for the reason in external circumstances. Both the aesthetic and the political attitude to literature were produced, or at any rate conditioned by the social atmosphere of a certain period. It is not that good books were not produced in that period. Several of the writers of that time, Dickens, Thackeray, Trollop and others, will probably be remembered longer than any that have come after them. But there are not literary figures in Victorian England corresponding to Flaubert, Baudelaire, Gautier and a host of others. What now appears to us as aesthetic scrupulousness hardly existed. To a mid-Victorian English writer, a book was partly something that brought him money and partly a vehicle for preaching sermons. England was changing very rapidly, a new moneyed class had come up on the ruins of the old aristocracy, contact with Europe had been severed, and a long artistic tradition had been broken. The mid-nineteenth-century English writers were barbarians, even when they happened to be gifted artists, like Dickens.

Which of the following would be the most suitable title for the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

If we look back at the English literature of the last ten years not so much at the literature as at the prevailing literary attitude, the thing that strikes us is that it has almost ceased to be aesthetic. Literature has been swamped by propaganda. I do not mean that all the books written during that period have been bad. But the characteristic writers of the time, people like Auden and Spender and MacNeice, have been didactic, political writers, aesthetically conscious, of course, but more interested in subject-matter than in technique.

This is all the more striking because it makes a very sharp and sudden contrast with the period immediately before it. The characteristic writers of the nineteen-twenties - T. S. Eliot, for instance, Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf - were writers who put the main emphasis on technique. They had their beliefs and prejudices, of course, but they were far more interested in technical innovations than in any moral or meaning or political implication that their work might contain. The best of them all, James Joyce, was a technician and very little else, about as near to being a 'pure' artist as a writer can be. Even D. H. Lawrence, though he was more of a 'writer with a purpose' than most of the others of his time, had not much of what we should now call social consciousness. And though I have narrowed this down to the nineteen-twenties, it had really been the same from about 1890 onwards. Throughout the whole of that period, the notion that form is more important than subject-matter, the notion of 'art for art's sake', had been taken for granted. There were writers who disagreed, of course - Bernard Shaw was one - but that was the prevailing outlook.

Now, how is one to account for this very sudden change of outlook? About the end of the nineteen-twenties you get a book like Edith Sitwell's book on Pope, with a completely frivolous emphasis on technique, treating literature as a sort of embroidery, almost as though words did not have meanings: and only a few years later you get a Marxist critic like Edward Upward asserting that books can be 'good' only when they are Marxist in tendency. In a sense both Edith Sitwell and Edward Upward were representative of their period. The question is why should their outlook be so different?

I think one has got to look for the reason in external circumstances. Both the aesthetic and the political attitude to literature were produced, or at any rate conditioned by the social atmosphere of a certain period. It is not that good books were not produced in that period. Several of the writers of that time, Dickens, Thackeray, Trollop and others, will probably be remembered longer than any that have come after them. But there are not literary figures in Victorian England corresponding to Flaubert, Baudelaire, Gautier and a host of others. What now appears to us as aesthetic scrupulousness hardly existed. To a mid-Victorian English writer, a book was partly something that brought him money and partly a vehicle for preaching sermons. England was changing very rapidly, a new moneyed class had come up on the ruins of the old aristocracy, contact with Europe had been severed, and a long artistic tradition had been broken. The mid-nineteenth-century English writers were barbarians, even when they happened to be gifted artists, like Dickens.

According to the passage, why does the author call the mid-nineteenth-century English writers, barbarians?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

If we look back at the English literature of the last ten years not so much at the literature as at the prevailing literary attitude, the thing that strikes us is that it has almost ceased to be aesthetic. Literature has been swamped by propaganda. I do not mean that all the books written during that period have been bad. But the characteristic writers of the time, people like Auden and Spender and MacNeice, have been didactic, political writers, aesthetically conscious, of course, but more interested in subject-matter than in technique.

This is all the more striking because it makes a very sharp and sudden contrast with the period immediately before it. The characteristic writers of the nineteen-twenties - T. S. Eliot, for instance, Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf - were writers who put the main emphasis on technique. They had their beliefs and prejudices, of course, but they were far more interested in technical innovations than in any moral or meaning or political implication that their work might contain. The best of them all, James Joyce, was a technician and very little else, about as near to being a 'pure' artist as a writer can be. Even D. H. Lawrence, though he was more of a 'writer with a purpose' than most of the others of his time, had not much of what we should now call social consciousness. And though I have narrowed this down to the nineteen-twenties, it had really been the same from about 1890 onwards. Throughout the whole of that period, the notion that form is more important than subject-matter, the notion of 'art for art's sake', had been taken for granted. There were writers who disagreed, of course - Bernard Shaw was one - but that was the prevailing outlook.

Now, how is one to account for this very sudden change of outlook? About the end of the nineteen-twenties you get a book like Edith Sitwell's book on Pope, with a completely frivolous emphasis on technique, treating literature as a sort of embroidery, almost as though words did not have meanings: and only a few years later you get a Marxist critic like Edward Upward asserting that books can be 'good' only when they are Marxist in tendency. In a sense both Edith Sitwell and Edward Upward were representative of their period. The question is why should their outlook be so different?

I think one has got to look for the reason in external circumstances. Both the aesthetic and the political attitude to literature were produced, or at any rate conditioned by the social atmosphere of a certain period. It is not that good books were not produced in that period. Several of the writers of that time, Dickens, Thackeray, Trollop and others, will probably be remembered longer than any that have come after them. But there are not literary figures in Victorian England corresponding to Flaubert, Baudelaire, Gautier and a host of others. What now appears to us as aesthetic scrupulousness hardly existed. To a mid-Victorian English writer, a book was partly something that brought him money and partly a vehicle for preaching sermons. England was changing very rapidly, a new moneyed class had come up on the ruins of the old aristocracy, contact with Europe had been severed, and a long artistic tradition had been broken. The mid-nineteenth-century English writers were barbarians, even when they happened to be gifted artists, like Dickens.

Which of the following statements can be inferred from the passage?

A survey of alumni of the class of 1960 at Arora University yielded puzzling results. When asked to indicate their academic rank, half of the respondents reported that they were in the top quarter of the graduating class in 1960.

Which one of the following most helps account for the apparent contradiction above?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow:

There are two parties to every observation---the observed and the observer

What we see depends not only on the object looked at, but on our own circumstances---position, motion, or more personal idiosyncrasies. Sometimes by instinctive habit, sometimes by design, we attempt to eliminate our own share in the observation, and so form a general picture of the world outside us, which shall be common to all observers. A small speck on the horizon of the sea is interpreted as a giant steamer. From the window of our railway carriage we see a cow glide past at fifty miles an hour, and remark that the creature is enjoying a rest. We see the starry heavens revolve round the earth, but decide that it is really the earth that is revolving, and so picture the state of the universe in a way which would be acceptable to an astronomer on any other planet.

The first step in throwing our knowledge into a common stock must be the elimination of the various individual standpoints and the reduction to some specified standard observer. The picture of the world so obtained is none the less relative. We have not eliminated the observer's share; we have only fixed it definitely.

To obtain a conception of the world from the point of view of no one in particular is a much more difficult task. The position of the observer can be eliminated; we are able to grasp the conception of a chair as an object in nature---looked at all round, and not from any particular angle or distance. We can think of it without mentally assigning ourselves some position with respect to it. This is a remarkable faculty, which has evidently been greatly assisted by the perception of solid relief with our two eyes. But the motion of the observer is not eliminated so simply. We had thought that it was accomplished; but the discovery that observers with different motions use different space- and time-reckoning shows that the matter is more complicated than was supposed. It may well require a complete change in our apparatus of description, because all the familiar terms of physics refer primarily to the relations of the world to an observer in some specified circumstances.

Whether we are able to go still further and obtain a knowledge of the world, which not merely does not particularise the observer, but does not postulate an observer at all; whether if such knowledge could be obtained, it would convey any intelligible meaning; and whether it could be of any conceivable interest to anybody if it could be understood---these questions need not detain us now. The answers are not necessarily negative, but they lie outside the normal scope of physics.

The circumstances of an observer which affect his observations are his position, motion and gauge of magnitude. More personal idiosyncracies disappear if, instead of relying on his crude senses, he employs scientific measuring apparatus. But scientific apparatus has position, motion and size, so that these are still involved in the results of any observation. There is no essential distinction between scientific measures and the measures of the senses. In either case our acquaintance with the external world comes to us through material channels; the observer's body can be regarded as part of his laboratory equipment, and, so far as we know, it obeys the same laws. We therefore group together perceptions and scientific measures, and in speaking of “a particular observer” we include all his measuring appliances.

Position, motion, magnitude-scale---these factors have a profound influence on the aspect of the world to us. Can we form a picture of the world which shall be a synthesis of what is seen by observers in all sorts of positions, having all sorts of velocities, and all sorts of sizes?

If, in one line, one has to identify the central objective of the author of the passage, it would be:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow:

There are two parties to every observation---the observed and the observer

What we see depends not only on the object looked at, but on our own circumstances---position, motion, or more personal idiosyncrasies. Sometimes by instinctive habit, sometimes by design, we attempt to eliminate our own share in the observation, and so form a general picture of the world outside us, which shall be common to all observers. A small speck on the horizon of the sea is interpreted as a giant steamer. From the window of our railway carriage we see a cow glide past at fifty miles an hour, and remark that the creature is enjoying a rest. We see the starry heavens revolve round the earth, but decide that it is really the earth that is revolving, and so picture the state of the universe in a way which would be acceptable to an astronomer on any other planet.

The first step in throwing our knowledge into a common stock must be the elimination of the various individual standpoints and the reduction to some specified standard observer. The picture of the world so obtained is none the less relative. We have not eliminated the observer's share; we have only fixed it definitely.

To obtain a conception of the world from the point of view of no one in particular is a much more difficult task. The position of the observer can be eliminated; we are able to grasp the conception of a chair as an object in nature---looked at all round, and not from any particular angle or distance. We can think of it without mentally assigning ourselves some position with respect to it. This is a remarkable faculty, which has evidently been greatly assisted by the perception of solid relief with our two eyes. But the motion of the observer is not eliminated so simply. We had thought that it was accomplished; but the discovery that observers with different motions use different space- and time-reckoning shows that the matter is more complicated than was supposed. It may well require a complete change in our apparatus of description, because all the familiar terms of physics refer primarily to the relations of the world to an observer in some specified circumstances.

Whether we are able to go still further and obtain a knowledge of the world, which not merely does not particularise the observer, but does not postulate an observer at all; whether if such knowledge could be obtained, it would convey any intelligible meaning; and whether it could be of any conceivable interest to anybody if it could be understood---these questions need not detain us now. The answers are not necessarily negative, but they lie outside the normal scope of physics.

The circumstances of an observer which affect his observations are his position, motion and gauge of magnitude. More personal idiosyncracies disappear if, instead of relying on his crude senses, he employs scientific measuring apparatus. But scientific apparatus has position, motion and size, so that these are still involved in the results of any observation. There is no essential distinction between scientific measures and the measures of the senses. In either case our acquaintance with the external world comes to us through material channels; the observer's body can be regarded as part of his laboratory equipment, and, so far as we know, it obeys the same laws. We therefore group together perceptions and scientific measures, and in speaking of “a particular observer” we include all his measuring appliances.

Position, motion, magnitude-scale---these factors have a profound influence on the aspect of the world to us. Can we form a picture of the world which shall be a synthesis of what is seen by observers in all sorts of positions, having all sorts of velocities, and all sorts of sizes?

As per the passage, which one of the following is true?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow:

There are two parties to every observation---the observed and the observer

What we see depends not only on the object looked at, but on our own circumstances---position, motion, or more personal idiosyncrasies. Sometimes by instinctive habit, sometimes by design, we attempt to eliminate our own share in the observation, and so form a general picture of the world outside us, which shall be common to all observers. A small speck on the horizon of the sea is interpreted as a giant steamer. From the window of our railway carriage we see a cow glide past at fifty miles an hour, and remark that the creature is enjoying a rest. We see the starry heavens revolve round the earth, but decide that it is really the earth that is revolving, and so picture the state of the universe in a way which would be acceptable to an astronomer on any other planet.

The first step in throwing our knowledge into a common stock must be the elimination of the various individual standpoints and the reduction to some specified standard observer. The picture of the world so obtained is none the less relative. We have not eliminated the observer's share; we have only fixed it definitely.

To obtain a conception of the world from the point of view of no one in particular is a much more difficult task. The position of the observer can be eliminated; we are able to grasp the conception of a chair as an object in nature---looked at all round, and not from any particular angle or distance. We can think of it without mentally assigning ourselves some position with respect to it. This is a remarkable faculty, which has evidently been greatly assisted by the perception of solid relief with our two eyes. But the motion of the observer is not eliminated so simply. We had thought that it was accomplished; but the discovery that observers with different motions use different space- and time-reckoning shows that the matter is more complicated than was supposed. It may well require a complete change in our apparatus of description, because all the familiar terms of physics refer primarily to the relations of the world to an observer in some specified circumstances.

Whether we are able to go still further and obtain a knowledge of the world, which not merely does not particularise the observer, but does not postulate an observer at all; whether if such knowledge could be obtained, it would convey any intelligible meaning; and whether it could be of any conceivable interest to anybody if it could be understood---these questions need not detain us now. The answers are not necessarily negative, but they lie outside the normal scope of physics.

The circumstances of an observer which affect his observations are his position, motion and gauge of magnitude. More personal idiosyncracies disappear if, instead of relying on his crude senses, he employs scientific measuring apparatus. But scientific apparatus has position, motion and size, so that these are still involved in the results of any observation. There is no essential distinction between scientific measures and the measures of the senses. In either case our acquaintance with the external world comes to us through material channels; the observer's body can be regarded as part of his laboratory equipment, and, so far as we know, it obeys the same laws. We therefore group together perceptions and scientific measures, and in speaking of “a particular observer” we include all his measuring appliances.

Position, motion, magnitude-scale---these factors have a profound influence on the aspect of the world to us. Can we form a picture of the world which shall be a synthesis of what is seen by observers in all sorts of positions, having all sorts of velocities, and all sorts of sizes?

As per the passage, the author believes that:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow:

There are two parties to every observation---the observed and the observer

What we see depends not only on the object looked at, but on our own circumstances---position, motion, or more personal idiosyncrasies. Sometimes by instinctive habit, sometimes by design, we attempt to eliminate our own share in the observation, and so form a general picture of the world outside us, which shall be common to all observers. A small speck on the horizon of the sea is interpreted as a giant steamer. From the window of our railway carriage we see a cow glide past at fifty miles an hour, and remark that the creature is enjoying a rest. We see the starry heavens revolve round the earth, but decide that it is really the earth that is revolving, and so picture the state of the universe in a way which would be acceptable to an astronomer on any other planet.

The first step in throwing our knowledge into a common stock must be the elimination of the various individual standpoints and the reduction to some specified standard observer. The picture of the world so obtained is none the less relative. We have not eliminated the observer's share; we have only fixed it definitely.

To obtain a conception of the world from the point of view of no one in particular is a much more difficult task. The position of the observer can be eliminated; we are able to grasp the conception of a chair as an object in nature---looked at all round, and not from any particular angle or distance. We can think of it without mentally assigning ourselves some position with respect to it. This is a remarkable faculty, which has evidently been greatly assisted by the perception of solid relief with our two eyes. But the motion of the observer is not eliminated so simply. We had thought that it was accomplished; but the discovery that observers with different motions use different space- and time-reckoning shows that the matter is more complicated than was supposed. It may well require a complete change in our apparatus of description, because all the familiar terms of physics refer primarily to the relations of the world to an observer in some specified circumstances.

Whether we are able to go still further and obtain a knowledge of the world, which not merely does not particularise the observer, but does not postulate an observer at all; whether if such knowledge could be obtained, it would convey any intelligible meaning; and whether it could be of any conceivable interest to anybody if it could be understood---these questions need not detain us now. The answers are not necessarily negative, but they lie outside the normal scope of physics.

The circumstances of an observer which affect his observations are his position, motion and gauge of magnitude. More personal idiosyncracies disappear if, instead of relying on his crude senses, he employs scientific measuring apparatus. But scientific apparatus has position, motion and size, so that these are still involved in the results of any observation. There is no essential distinction between scientific measures and the measures of the senses. In either case our acquaintance with the external world comes to us through material channels; the observer's body can be regarded as part of his laboratory equipment, and, so far as we know, it obeys the same laws. We therefore group together perceptions and scientific measures, and in speaking of “a particular observer” we include all his measuring appliances.

Position, motion, magnitude-scale---these factors have a profound influence on the aspect of the world to us. Can we form a picture of the world which shall be a synthesis of what is seen by observers in all sorts of positions, having all sorts of velocities, and all sorts of sizes?

Which, out of the following statements, will be an appropriate continuation for the passage?

Replace the underlined portion of the given sentences with the option that makes the sentence grammatically and contextually correct

The bitter cold the Midwest is experiencing is potentially life threatening to stranded motorists unless well-insulated with protective clothing.

Read the following sentences and choose the one the option that best arranges them in a logical order.

1. My eyes turned instinctively in that direction, and I saw a figure leap with great rapidity behind the trunk of a pine.

2. It seemed dark and shaggy; more I knew not but the terror of this new apparition brought me to a stand.

3. From the side of the hill, which was here steep and stony, a spout of gravel was dislodged and fell rattling and bounding through the trees.

4. What it was, whether bear or man or monkey, I could in no wise tell.

Directions: Read the poem carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveller, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I -

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

What is the poet's feeling about the road which he selected in the beginning of his journey?

Directions: Read the poem carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveller, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I -

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

What does the poet imply when he says, "Yet knowing how way leads on to way"?

Each sentence below has two blanks, each blank indicating that something has been omitted. Choose the set of words for each blank that best fits the meaning of the sentence as a whole.

In HIV/AIDS affected communities, marriage might be seen as a way to protect against __________ the disease. Bracher, for example, is motivated by the idea that in Malawi and elsewhere in the region marriage is increasingly believed to protect young women from HIV since it may reduce __________ sexual behavior, in which case women may be encouraged to marry early.

Identify the correct sequence of words that would most aptly fit the blanks in the following passage.

The people kept the street in which he lay quiet; but medical care, the loving ____ (i) ______ of friends, and the respect of all the people could not save his life. There was a surge of people who wanted to see him for the last time and it was difficult for the security personnel to control the _____(ii) _____ crowd. His family members chose to be ____(iii) ____ and refused to comment anything on the cause of death. The ____(iv) _____ cause of death is still unknown. Hence, it can be ____(v) ____ that perhaps he died under mysterious circumstances.

Six words are given below

i. Diminutive

ii. Minuscule

iii. Homuncular

iv. Avuncular

v. Homozygous

vi. Bonhomous

Which of the above words have similar meanings?

Which of the following is not a term for 'being in absolute poverty'

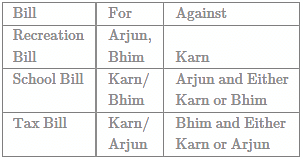

DIRECTIONS: Krishnapuram's town council has exactly three members: Arjun, Karn, and Bhim. During one week, the council members vote on exactly three bills: a recreation bill, a school bill, and a tax bill. Each council member votes either for or against each bill. The following is known:

Each member of the council votes for at least one of the bills and against at least one of the bills.

Exactly two members of the council vote for the recreation bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the school bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the tax bill.

Arjun votes for the recreation bill and against the school bill.

Karn votes against the recreation bill.

Bhim votes against the tax bill.

If the set of members of the council who vote against the school bill are the only ones who also vote against the tax bill, then which one of the following statements must be true?

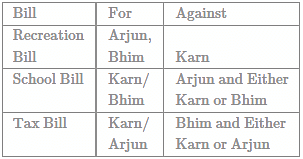

DIRECTIONS: Krishnapuram's town council has exactly three members: Arjun, Karn, and Bhim. During one week, the council members vote on exactly three bills: a recreation bill, a school bill, and a tax bill. Each council member votes either for or against each bill. The following is known:

Each member of the council votes for at least one of the bills and against at least one of the bills.

Exactly two members of the council vote for the recreation bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the school bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the tax bill.

Arjun votes for the recreation bill and against the school bill.

Karn votes against the recreation bill.

Bhim votes against the tax bill.

If Karn votes for the tax bill, then which one of the following statements could be true?:

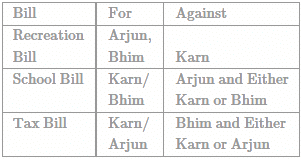

DIRECTIONS: Krishnapuram's town council has exactly three members: Arjun, Karn, and Bhim. During one week, the council members vote on exactly three bills: a recreation bill, a school bill, and a tax bill. Each council member votes either for or against each bill. The following is known:

Each member of the council votes for at least one of the bills and against at least one of the bills.

Exactly two members of the council vote for the recreation bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the school bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the tax bill.

Arjun votes for the recreation bill and against the school bill.

Karn votes against the recreation bill.

Bhim votes against the tax bill.

Karn votes for exactly two of the three bills, which one of the following statements must be true?

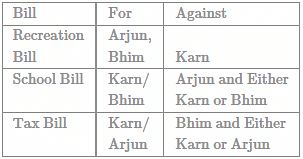

DIRECTIONS: Krishnapuram's town council has exactly three members: Arjun, Karn, and Bhim. During one week, the council members vote on exactly three bills: a recreation bill, a school bill, and a tax bill. Each council member votes either for or against each bill. The following is known:

Each member of the council votes for at least one of the bills and against at least one of the bills.

Exactly two members of the council vote for the recreation bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the school bill.

Exactly one member of the council votes for the tax bill.

Arjun votes for the recreation bill and against the school bill.

Karn votes against the recreation bill.

Bhim votes against the tax bill.

If one of the members of the council votes against exactly the same bills as does another member of the council, then which one of the following statements must be true?

|

16 docs|30 tests

|