OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 7 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test Digital SAT Mock Test Series 2024 - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 7

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

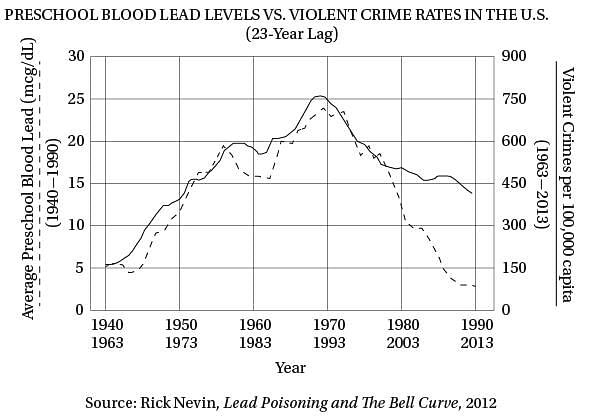

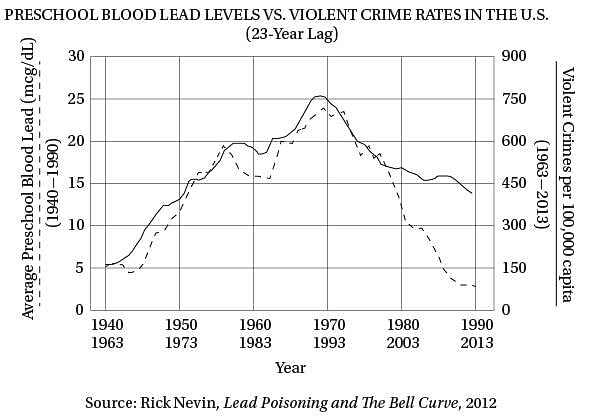

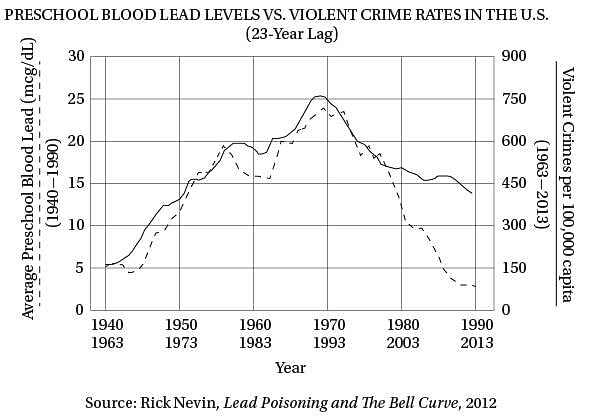

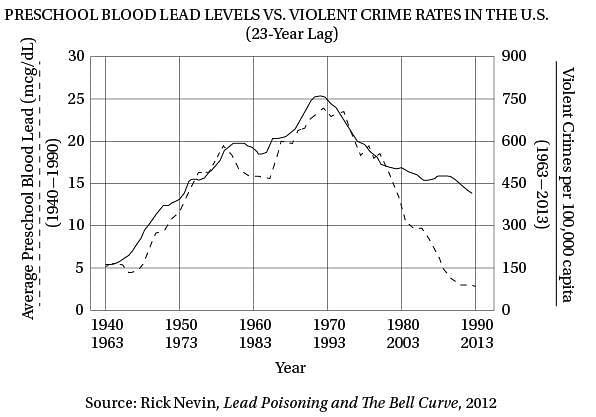

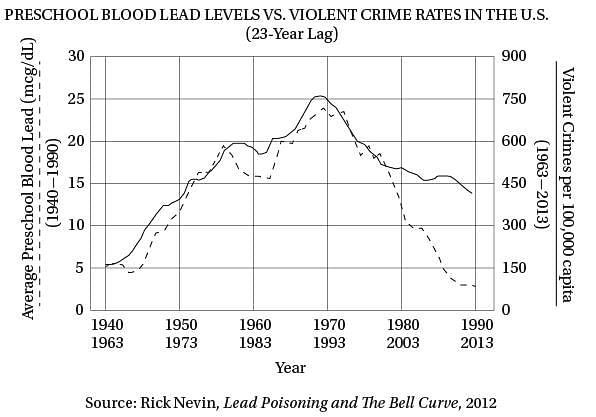

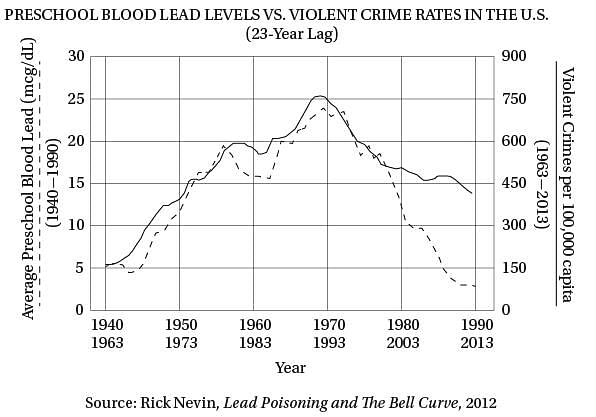

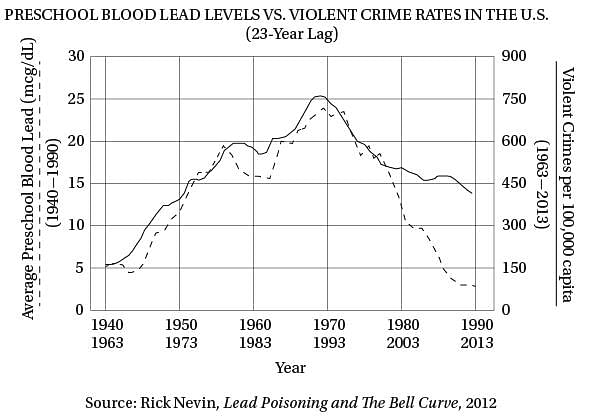

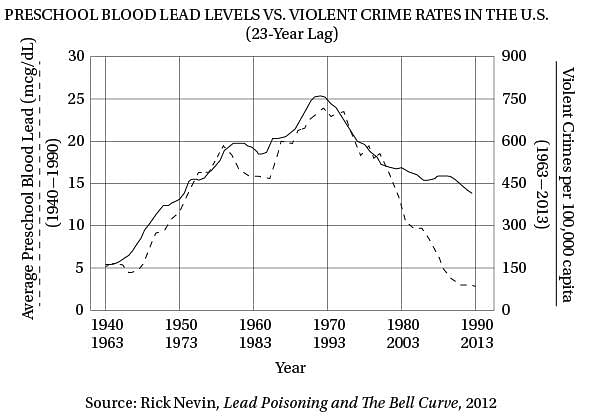

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

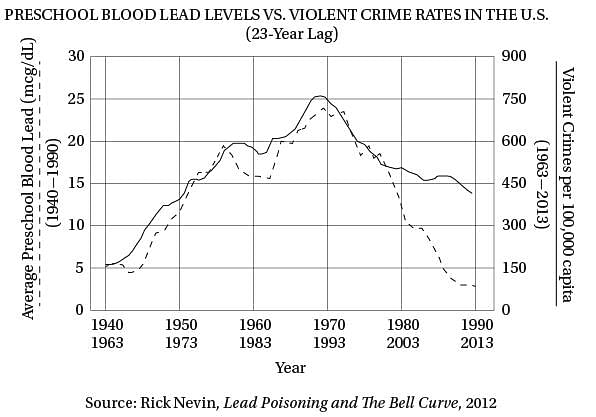

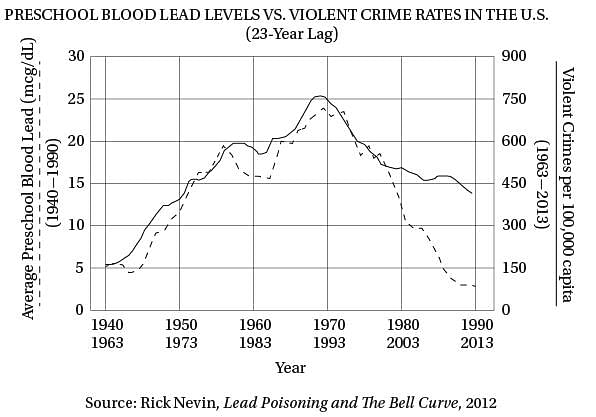

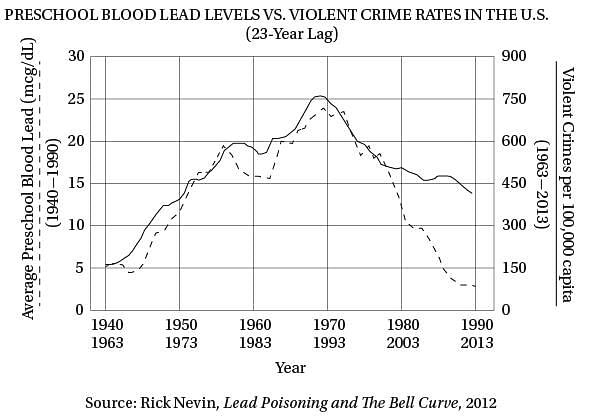

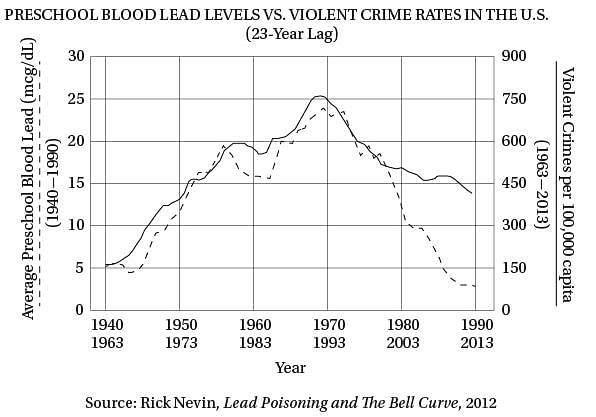

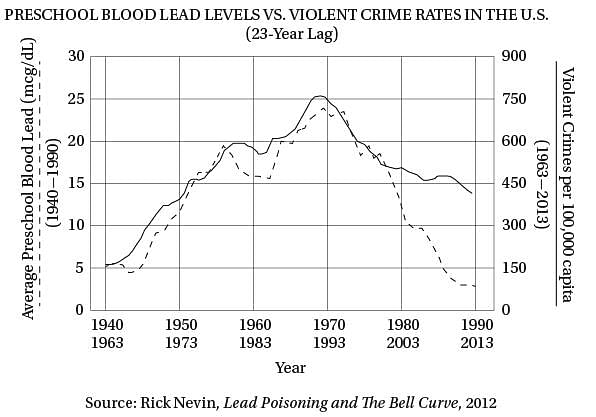

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. In the first paragraph, Karl Smith’s work is presented primarily as

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. The author suggests that promising research in the social sciences is sometimes ignored because it

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. Which of the following provides the strongest evidence for the answer to the previous question?

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. According to the graph for which of the following time periods was the percent increase in per capita violent crime the greatest?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. According to the graph, which decade of violent crime statistics provides the LEAST support to Rick Nevin’s hypothesis?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. The author mentions “sales of vinyl LPs” (line 74) primarily as an example of

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. The “complications” in line 22 are

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. The author regards the “drivers” in line 60 as

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. In line 49, “even better” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Kevin Drum, “America's Real Criminal Element: Lead" ©2013 Mother Jones.

Experts often suggest that crime resembles

an epidemic. But what kind? Economics

professor Karl Smith has a good rule of thumb

for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along

(5) lines of communication, he says, the cause is

information. Think Bieber Fever.* If it travels

along major transportation routes, the cause is

microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like

a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But

(10) if it's everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of

crime in the '60s and '70s and the fall of crime in

the '90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

A molecule? That sounds crazy. What

molecule could be responsible for a steep and

(15) sudden decline in violent crime?

Well, here's one possibility: Pb(CH2CH3)4.

In 1994, Rick Nevin was a consultant

working for the US Department of Housing and

Urban Development on the costs and benefits of

(20) removing lead paint from old houses. A growing

body of research had linked lead exposure in

small children with a whole raft of complications

later in life, including lower IQ, hyperactivity,

behavioral problems, and learning disabilities.

(25) A recent study had also suggested a link

between childhood lead exposure and juvenile

delinquency later on. Maybe reducing lead

exposure had an effect on violent crime too?

That tip took Nevin in a different direction. The

(30) biggest source of lead in the postwar era, it turns

out, wasn't paint, but leaded gasoline. If you chart

the rise and fall of atmospheric lead caused by

the rise and fall of leaded gasoline consumption,

you get an upside-down U. Lead emissions from

(35) tailpipes rose steadily from the early '40s through

the early '70s, nearly quadrupling over that period.

Then, as unleaded gasoline began to replace leaded

gasoline, emissions plummeted.

Intriguingly, violent crime rates followed the

(40) same upside-down U pattern (see the graph). The

only thing different was the time period. Crime

rates rose dramatically in the '60s through the

'80s, and then began dropping steadily starting

in the early '90s. The two curves looked eerily

(45) identical, but were offset by about 20 years.

So Nevin dug up detailed data on lead

emissions and crime rates to see if the similarity

of the curves was as good as it seemed. It turned

out to be even better. In a 2000 paper he concluded

(50) that if you add a lag time of 23 years, lead

emissions from automobiles explain 90 percent of

the variation in violent crime in America. Toddlers

who ingested high levels of lead in the '40s and

'50s really were more likely to become violent

(55) criminals in the '60s, '70s, and '80s.

And with that we have our molecule: tetra-

ethyl lead, the gasoline additive invented by

General Motors in the 1920s to prevent knocking

and pinging in high-performance engines. As

(60) auto sales boomed after World War II, and drivers

in powerful new cars increasingly asked service

station attendants to “fill 'er up with ethyl,” they

were unwittingly creating a crime wave two

decades later.

(65) It was an exciting conjecture, and it

prompted an immediate wave of . . . nothing.

Nevin's paper was almost completely ignored,

and in one sense it's easy to see why—Nevin is

an economist, not a criminologist, and his paper

(70) was published in Environmental Research, not a

journal with a big readership in the criminology

community. What's more, a single correlation

between two curves isn't all that impressive,

econometrically speaking. Sales of vinyl LPs rose

(75) in the postwar period too, and then declined in

the '80s and '90s. No matter how good the fit, if

you only have a single correlation it might just be

a coincidence. You need to do something more to

establish causality.

(80) So in 2007, Nevin collected lead data and

crime data for Australia, Canada, Great Britain,

Finland, France, Italy, New Zealand and West

Germany. Every time, the two curves fit each other

astonishingly well.

(85) The gasoline lead hypothesis helps explain

some things we might not have realized even

needed explaining. For example, murder rates

have always been higher in big cities than in

towns and small cities. Nevin suggests that,

(90) because big cities have lots of cars in a small

area, they also had high densities of atmospheric

lead during the postwar era. But as lead levels

in gasoline decreased, the differences between

big and small cities largely went away. And guess

(95) what? The difference in murder rates went away

too. Today, homicide rates are similar in cities

of all sizes. It may be that violent crime isn't an

inevitable consequence of being a big city after all.

*Enthusiasm for the music and person of Justin Bieber.

Q. The final paragraph (lines 85–98) serves primarily to

Question based on the following passages.

Passage 1 is adapted from an essay written by John Aldridge in 1951. ©1951 by John Aldridge. Passage 2 is adapted from Brom Weber, "Ernest Hemingway's Genteel Bullfight," published in The American Novel and the Nineteen Twenties. ©1971 by Hodder Education.

Passage 1

By the time we were old enough to read

Hemingway, he had become legendary. Like

Lord Byron a century earlier, he had learned

to play himself, his own best hero, with superb

(5) conviction. He was Hemingway of the rugged

outdoor grin and the hairy chest posing beside a

lion he had just shot. He was Tarzan Hemingway,

crouching in the African bush with elephant gun

at ready. He was War Correspondent Hemingway

(10) writing a play in the Hotel Florida in Madrid

while thirty fascist shells crashed through

the roof. Later, he was Task Force Hemingway

swathed in ammunition belts and defending

his post singlehandedly against fierce German

(15) attacks.

But even without the legend, the chest

beating, wisecracking pose that was later to

seem so incredibly absurd, his impact upon us

was tremendous. The feeling he gave us was one

(20) of immense expansiveness, freedom and, at the

same time, absolute stability and control. We

could follow him, imitate his cold detachment,

through all the doubts and fears of adolescence

and come out pure and untouched. The words

(25) he put down seemed to us to have been carved

from the living stone of life. They conveyed

exactly the taste, smell and feel of experience as

it was, as it might possibly be. And so we began

unconsciously to translate our own sensations

(30) into their terms and to impose on everything

we did and felt the particular emotions they

aroused in us.

The Hemingway time was a good time to

be young. We had much then that the war later

(35) forced out of us, something far greater than

Hemingway's strong formative influence.

Later writers who lost or got rid of Hemingway

have been able to find nothing to put in his

place. They have rejected his time as untrue

(40) for them only to fail at finding themselves in their

own time. Others, in their embarrassment at the

hold he once had over them, have not profited

by the lessons he had to teach, and still others

were never touched by him at all. These last are

(45) perhaps the real unfortunates, for they have been

denied access to a powerful tradition.

Passage 2

One wonders why Hemingway's greatest

works now seem unable to evoke the same sense

of a tottering world that in the 1920s established

(50) Ernest Hemingway's reputation. These novels

should be speaking to us. Our social structure

is as shaken, our philosophical despair as great,

our everyday experience as unsatisfying. We have

had more war than Hemingway ever dreamed

(55) of. Our violence—physical, emotional, and

intellectual—is not inferior to that of the 1920s.

Yet Hemingway's great novels no longer seem to

penetrate deeply the surface of existence.

One begins to doubt that they ever did so significantly

(60) in the 1920s.

Hemingway's novels indulged the dominant

genteel tradition in American culture while

seeming to repudiate it. They yielded to the

functionalist, technological aesthetic of the

(65) culture instead of resisting in the manner of

Frank Lloyd Wright. Hemingway, in effect, became a

dupe of his culture rather than its moral-aesthetic

conscience. As a consequence, the import of his

work has diminished. There is some evidence

(70) from his stylistic evolution that Hemingway

himself must have felt as much, for Hemingway's

famous stylistic economy frequently seems to

conceal another kind of writer, with much richer

rhetorical resources to hand. So, Death in the

(75) Afternoon (1932), Hemingway's bullfighting

opus and his first book after A Farewell to Arms

(1929), reveals great uneasiness over his earlier

accomplishment. In it, he defends his literary

method with a doctrine of ambiguity: “If a writer

(80) of prose knows enough about what he is writing

about he may omit things that he knows and

the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough,

will have a feeling of those things as strongly as

though the writer had stated them.”

(85) Hemingway made much the same theoretical

point in another way in Death in the Afternoon

apparently believing that a formal reduction of

aesthetic complexity was the only kind of design

that had value.

(90) Perhaps the greatest irony of Death in the

Afternoon is its unmistakably baroque prose,

which Hemingway himself embarrassedly

admitted was “flowery.” Reviewers, unable to

challenge Hemingway's expertise in the art of

(95) bullfighting, noted that its style was “awkward,

tortuous, [and] belligerently clumsy.”

Death in the Afternoon is an extraordinarily

self-indulgent, unruly, clownish, garrulous,

and satiric book, with scrambled chronologies,

(100) willful digressions, mock-scholarly apparatuses,

fictional interludes, and scathing allusions. Its

inflated style can hardly penetrate the fagade, let

alone deflate humanity.

Q. On which topic do the authors of the two passages most strongly disagree?

Question based on the following passages.

Passage 1 is adapted from an essay written by John Aldridge in 1951. ©1951 by John Aldridge. Passage 2 is adapted from Brom Weber, "Ernest Hemingway's Genteel Bullfight," published in The American Novel and the Nineteen Twenties. ©1971 by Hodder Education.

Passage 1

By the time we were old enough to read

Hemingway, he had become legendary. Like

Lord Byron a century earlier, he had learned

to play himself, his own best hero, with superb

(5) conviction. He was Hemingway of the rugged

outdoor grin and the hairy chest posing beside a

lion he had just shot. He was Tarzan Hemingway,

crouching in the African bush with elephant gun

at ready. He was War Correspondent Hemingway

(10) writing a play in the Hotel Florida in Madrid

while thirty fascist shells crashed through

the roof. Later, he was Task Force Hemingway

swathed in ammunition belts and defending

his post singlehandedly against fierce German

(15) attacks.

But even without the legend, the chest

beating, wisecracking pose that was later to

seem so incredibly absurd, his impact upon us

was tremendous. The feeling he gave us was one

(20) of immense expansiveness, freedom and, at the

same time, absolute stability and control. We

could follow him, imitate his cold detachment,

through all the doubts and fears of adolescence

and come out pure and untouched. The words

(25) he put down seemed to us to have been carved

from the living stone of life. They conveyed

exactly the taste, smell and feel of experience as

it was, as it might possibly be. And so we began

unconsciously to translate our own sensations

(30) into their terms and to impose on everything

we did and felt the particular emotions they

aroused in us.

The Hemingway time was a good time to

be young. We had much then that the war later

(35) forced out of us, something far greater than

Hemingway's strong formative influence.

Later writers who lost or got rid of Hemingway

have been able to find nothing to put in his

place. They have rejected his time as untrue

(40) for them only to fail at finding themselves in their

own time. Others, in their embarrassment at the

hold he once had over them, have not profited