Test: Practice Test - 2 - Class 10 MCQ

20 Questions MCQ Test The Complete SAT Course - Test: Practice Test - 2

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. Which choice best summarizes the passage?

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. The main purpose of the opening sentence of the passage is to

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. During the course of the first paragraph, the narrator’s focus shifts from

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. The references to “shade” and “darkness” at the end of the first paragraph mainly have which effect?

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. The passage indicates that Edward Crimsworth’s behavior was mainly caused by his

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. The passage indicates that when the narrator began working for Edward Crimsworth, he viewed Crimsworth as a

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. At the end of the second paragraph, the comparisons of abstract qualities to a lynx and a snake mainly have the effect of

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. The passage indicates that, after a long day of work, the narrator sometimes found his living quarters to be

Question is based on the following passage.

This passage is from Charlotte Brontë, The Professor, originally published in 1857.

No man likes to acknowledge that he has made a

mistake in the choice of his profession, and every

man, worthy of the name, will row long against wind

and tide before he allows himself to cry out, “I am

5 baffled!” and submits to be floated passively back to

land. From the first week of my residence in X—

felt my occupation irksome. The thing itself—the

work of copying and translating business-letters—

was a dry and tedious task enough, but had that been

10 all, I should long have borne with the nuisance; I am

not of an impatient nature, and influenced by the

double desire of getting my living and justifying to

myself and others the resolution I had taken to

become a tradesman, I should have endured in

15 silence the rust and cramp of my best faculties; I

should not have whispered, even inwardly, that I

longed for liberty; I should have pent in every sigh by

which my heart might have ventured to intimate its

distress under the closeness, smoke, monotony, and

20 joyless tumult of Bigben Close, and its panting desire

for freer and fresher scenes; I should have set up the

image of Duty, the fetish of Perseverance, in my

small bedroom at Mrs. King’s lodgings, and they two

should have been my household gods, from which

25 my darling, my cherished-in-secret, Imagination, the

tender and the mighty, should never, either by

softness or strength, have severed me. But this was

not all; the antipathy which had sprung up between

myself and my employer striking deeper root and

30 spreading denser shade daily, excluded me from

every glimpse of the sunshine of life; and I began to

feel like a plant growing in humid darkness out of the

slimy walls of a well.

Antipathy is the only word which can express the

35 feeling Edward Crimsworth had for me—a feeling, in

a great measure, involuntary, and which was liable to

be excited by every, the most trifling movement,

look, or word of mine. My southern accent annoyed

him; the degree of education evinced in my language

40 irritated him; my punctuality, industry, and

accuracy, fixed his dislike, and gave it the high

flavour and poignant relish of envy; he feared that I

too should one day make a successful tradesman.

Had I been in anything inferior to him, he would not

45 have hated me so thoroughly, but I knew all that he

knew, and, what was worse, he suspected that I kept

the padlock of silence on mental wealth in which he

was no sharer. If he could have once placed me in a

ridiculous or mortifying position, he would have

50 forgiven me much, but I was guarded by three

faculties—Caution, Tact, Observation; and prowling

and prying as was Edward’s malignity, it could never

baffle the lynx-eyes of these, my natural sentinels.

Day by day did his malice watch my tact, hoping it

55 would sleep, and prepared to steal snake-like on its

slumber; but tact, if it be genuine, never sleeps.

I had received my first quarter’s wages, and was

returning to my lodgings, possessed heart and soul

with the pleasant feeling that the master who had

60 paid me grudged every penny of that hard‑earned

pittance—(I had long ceased to regard

Mr. Crimsworth as my brother—he was a hard,

grinding master; he wished to be an inexorable

tyrant: that was all). Thoughts, not varied but strong,

65 occupied my mind; two voices spoke within me;

again and again they uttered the same monotonous

phrases. One said: “William, your life is intolerable.”

The other: “What can you do to alter it?” I walked

fast, for it was a cold, frosty night in January; as I

70 approached my lodgings, I turned from a general

view of my affairs to the particular speculation as to

whether my fire would be out; looking towards the

window of my sitting-room, I saw no cheering red

gleam.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

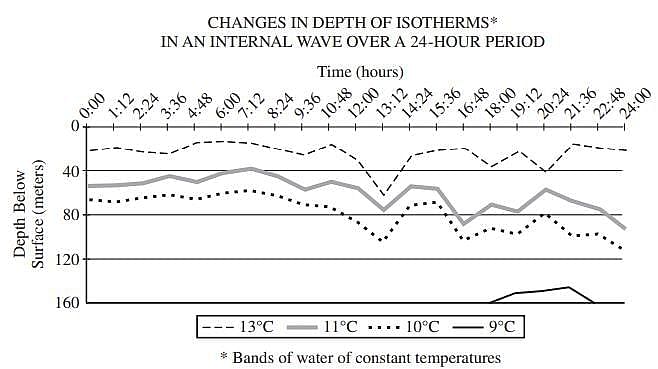

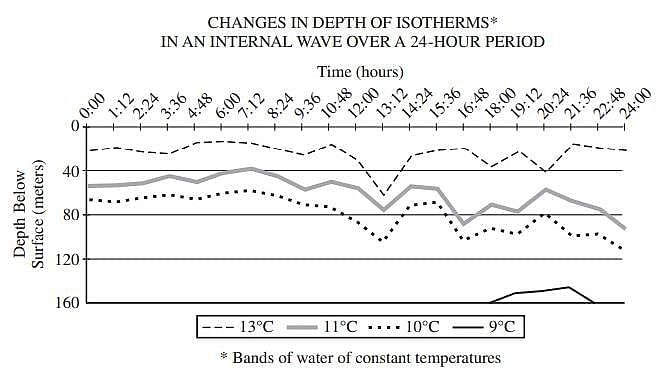

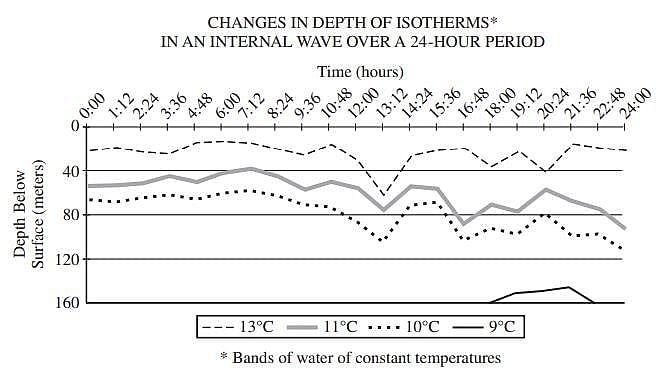

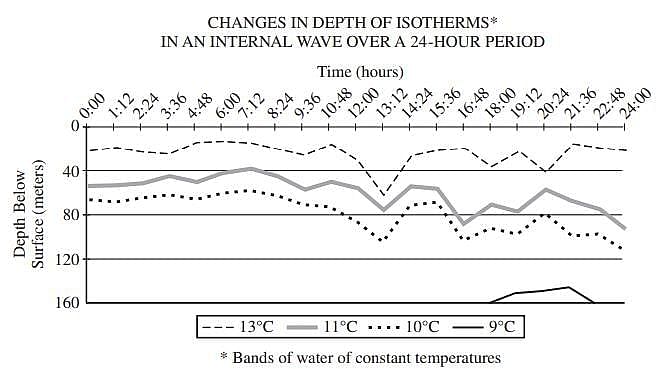

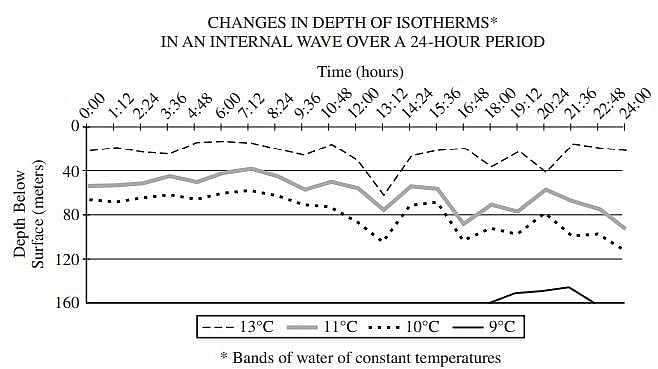

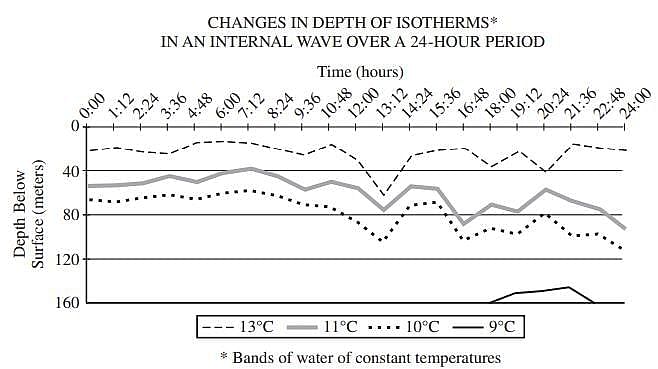

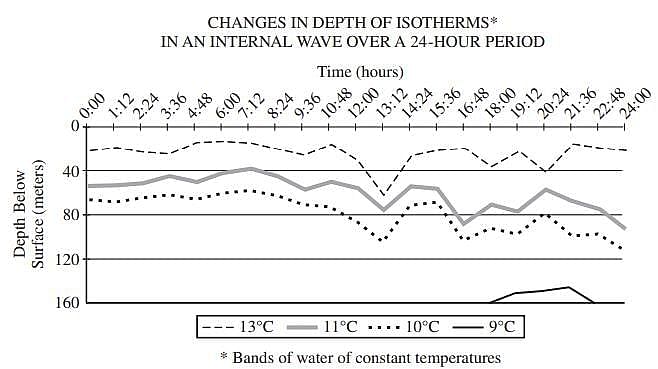

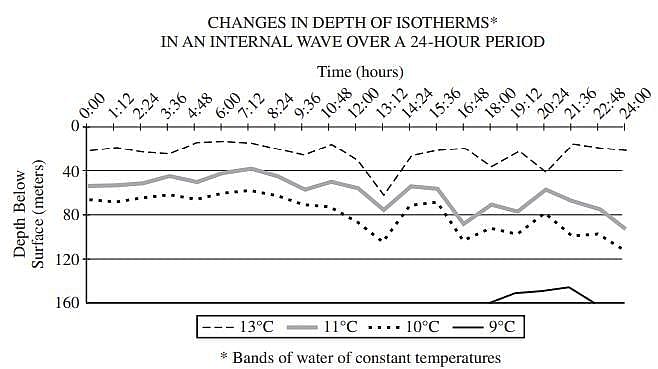

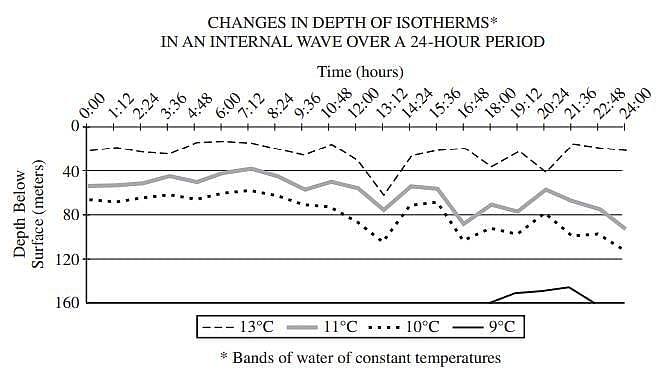

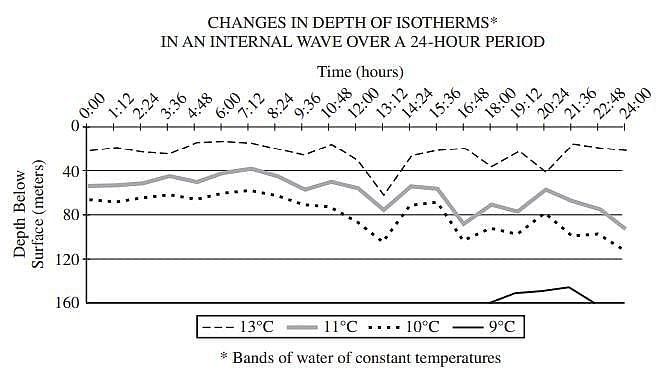

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing

and thus the transfer of heat, understanding them is

crucial to global climate modeling, says Tom

15 Peacock, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. Most models fail to take internal

waves into account. “If we want to have more and

more accurate climate models, we have to be able to

capture processes such as this,” Peacock says.

20 Peacock and his colleagues tried to do just that.

Their study, published in November in Geophysical

Research Letters, focused on internal waves generated

in the Luzon Strait, which separates Taiwan and the

Philippines. Internal waves in this region, thought to

25 be some of the largest in the world, can reach about

500 meters high. “That’s the same height as the

Freedom Tower that’s just been built in New York,”

Peacock says.

Although scientists knew of this phenomenon in

30 the South China Sea and beyond, they didn’t know

exactly how internal waves formed. To find out,

Peacock and a team of researchers from M.I.T. and

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worked with

France’s National Center for Scientific Research

35 using a giant facility there called the Coriolis

Platform. The rotating platform, about 15 meters

(49.2 feet) in diameter, turns at variable speeds and

can simulate Earth’s rotation. It also has walls, which

means scientists can fill it with water and create

40 accurate, large-scale simulations of various

oceanographic scenarios.

Peacock and his team built a carbon-fiber resin

scale model of the Luzon Strait, including the islands

and surrounding ocean floor topography. Then they

45 filled the platform with water of varying salinity to

replicate the different densities found at the strait,

with denser, saltier water below and lighter, less

briny water above. Small particles were added to the

solution and illuminated with lights from below in

50 order to track how the liquid moved. Finally, they

re-created tides using two large plungers to see how

the internal waves themselves formed.

The Luzon Strait’s underwater topography, with a

distinct double-ridge shape, turns out to be

55 responsible for generating the underwater waves.

As the tide rises and falls and water moves through

the strait, colder, denser water is pushed up over the

ridges into warmer, less dense layers above it.

This action results in bumps of colder water trailed

60 by warmer water that generate an internal wave.

As these waves move toward land, they become

steeper—much the same way waves at the beach

become taller before they hit the shore—until they

break on a continental shelf.

65 The researchers were also able to devise a

mathematical model that describes the movement

and formation of these waves. Whereas the model is

specific to the Luzon Strait, it can still help

researchers understand how internal waves are

70 generated in other places around the world.

Eventually, this information will be incorporated into

global climate models, making them more accurate.

“It’s very clear, within the context of these [global

climate] models, that internal waves play a role in

75 driving ocean circulations,” Peacock says.

Q. The first paragraph serves mainly to

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing

and thus the transfer of heat, understanding them is

crucial to global climate modeling, says Tom

15 Peacock, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. Most models fail to take internal

waves into account. “If we want to have more and

more accurate climate models, we have to be able to

capture processes such as this,” Peacock says.

20 Peacock and his colleagues tried to do just that.

Their study, published in November in Geophysical

Research Letters, focused on internal waves generated

in the Luzon Strait, which separates Taiwan and the

Philippines. Internal waves in this region, thought to

25 be some of the largest in the world, can reach about

500 meters high. “That’s the same height as the

Freedom Tower that’s just been built in New York,”

Peacock says.

Although scientists knew of this phenomenon in

30 the South China Sea and beyond, they didn’t know

exactly how internal waves formed. To find out,

Peacock and a team of researchers from M.I.T. and

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worked with

France’s National Center for Scientific Research

35 using a giant facility there called the Coriolis

Platform. The rotating platform, about 15 meters

(49.2 feet) in diameter, turns at variable speeds and

can simulate Earth’s rotation. It also has walls, which

means scientists can fill it with water and create

40 accurate, large-scale simulations of various

oceanographic scenarios.

Peacock and his team built a carbon-fiber resin

scale model of the Luzon Strait, including the islands

and surrounding ocean floor topography. Then they

45 filled the platform with water of varying salinity to

replicate the different densities found at the strait,

with denser, saltier water below and lighter, less

briny water above. Small particles were added to the

solution and illuminated with lights from below in

50 order to track how the liquid moved. Finally, they

re-created tides using two large plungers to see how

the internal waves themselves formed.

The Luzon Strait’s underwater topography, with a

distinct double-ridge shape, turns out to be

55 responsible for generating the underwater waves.

As the tide rises and falls and water moves through

the strait, colder, denser water is pushed up over the

ridges into warmer, less dense layers above it.

This action results in bumps of colder water trailed

60 by warmer water that generate an internal wave.

As these waves move toward land, they become

steeper—much the same way waves at the beach

become taller before they hit the shore—until they

break on a continental shelf.

65 The researchers were also able to devise a

mathematical model that describes the movement

and formation of these waves. Whereas the model is

specific to the Luzon Strait, it can still help

researchers understand how internal waves are

70 generated in other places around the world.

Eventually, this information will be incorporated into

global climate models, making them more accurate.

“It’s very clear, within the context of these [global

climate] models, that internal waves play a role in

75 driving ocean circulations,” Peacock says.

Q. As used in line 19, “capture” is closest in meaning to

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing

and thus the transfer of heat, understanding them is

crucial to global climate modeling, says Tom

15 Peacock, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. Most models fail to take internal

waves into account. “If we want to have more and

more accurate climate models, we have to be able to

capture processes such as this,” Peacock says.

20 Peacock and his colleagues tried to do just that.

Their study, published in November in Geophysical

Research Letters, focused on internal waves generated

in the Luzon Strait, which separates Taiwan and the

Philippines. Internal waves in this region, thought to

25 be some of the largest in the world, can reach about

500 meters high. “That’s the same height as the

Freedom Tower that’s just been built in New York,”

Peacock says.

Although scientists knew of this phenomenon in

30 the South China Sea and beyond, they didn’t know

exactly how internal waves formed. To find out,

Peacock and a team of researchers from M.I.T. and

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worked with

France’s National Center for Scientific Research

35 using a giant facility there called the Coriolis

Platform. The rotating platform, about 15 meters

(49.2 feet) in diameter, turns at variable speeds and

can simulate Earth’s rotation. It also has walls, which

means scientists can fill it with water and create

40 accurate, large-scale simulations of various

oceanographic scenarios.

Peacock and his team built a carbon-fiber resin

scale model of the Luzon Strait, including the islands

and surrounding ocean floor topography. Then they

45 filled the platform with water of varying salinity to

replicate the different densities found at the strait,

with denser, saltier water below and lighter, less

briny water above. Small particles were added to the

solution and illuminated with lights from below in

50 order to track how the liquid moved. Finally, they

re-created tides using two large plungers to see how

the internal waves themselves formed.

The Luzon Strait’s underwater topography, with a

distinct double-ridge shape, turns out to be

55 responsible for generating the underwater waves.

As the tide rises and falls and water moves through

the strait, colder, denser water is pushed up over the

ridges into warmer, less dense layers above it.

This action results in bumps of colder water trailed

60 by warmer water that generate an internal wave.

As these waves move toward land, they become

steeper—much the same way waves at the beach

become taller before they hit the shore—until they

break on a continental shelf.

65 The researchers were also able to devise a

mathematical model that describes the movement

and formation of these waves. Whereas the model is

specific to the Luzon Strait, it can still help

researchers understand how internal waves are

70 generated in other places around the world.

Eventually, this information will be incorporated into

global climate models, making them more accurate.

“It’s very clear, within the context of these [global

climate] models, that internal waves play a role in

75 driving ocean circulations,” Peacock says.

Q. According to Peacock, the ability to monitor internal waves is significant primarily because

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing

and thus the transfer of heat, understanding them is

crucial to global climate modeling, says Tom

15 Peacock, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. Most models fail to take internal

waves into account. “If we want to have more and

more accurate climate models, we have to be able to

capture processes such as this,” Peacock says.

20 Peacock and his colleagues tried to do just that.

Their study, published in November in Geophysical

Research Letters, focused on internal waves generated

in the Luzon Strait, which separates Taiwan and the

Philippines. Internal waves in this region, thought to

25 be some of the largest in the world, can reach about

500 meters high. “That’s the same height as the

Freedom Tower that’s just been built in New York,”

Peacock says.

Although scientists knew of this phenomenon in

30 the South China Sea and beyond, they didn’t know

exactly how internal waves formed. To find out,

Peacock and a team of researchers from M.I.T. and

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worked with

France’s National Center for Scientific Research

35 using a giant facility there called the Coriolis

Platform. The rotating platform, about 15 meters

(49.2 feet) in diameter, turns at variable speeds and

can simulate Earth’s rotation. It also has walls, which

means scientists can fill it with water and create

40 accurate, large-scale simulations of various

oceanographic scenarios.

Peacock and his team built a carbon-fiber resin

scale model of the Luzon Strait, including the islands

and surrounding ocean floor topography. Then they

45 filled the platform with water of varying salinity to

replicate the different densities found at the strait,

with denser, saltier water below and lighter, less

briny water above. Small particles were added to the

solution and illuminated with lights from below in

50 order to track how the liquid moved. Finally, they

re-created tides using two large plungers to see how

the internal waves themselves formed.

The Luzon Strait’s underwater topography, with a

distinct double-ridge shape, turns out to be

55 responsible for generating the underwater waves.

As the tide rises and falls and water moves through

the strait, colder, denser water is pushed up over the

ridges into warmer, less dense layers above it.

This action results in bumps of colder water trailed

60 by warmer water that generate an internal wave.

As these waves move toward land, they become

steeper—much the same way waves at the beach

become taller before they hit the shore—until they

break on a continental shelf.

65 The researchers were also able to devise a

mathematical model that describes the movement

and formation of these waves. Whereas the model is

specific to the Luzon Strait, it can still help

researchers understand how internal waves are

70 generated in other places around the world.

Eventually, this information will be incorporated into

global climate models, making them more accurate.

“It’s very clear, within the context of these [global

climate] models, that internal waves play a role in

75 driving ocean circulations,” Peacock says.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing

and thus the transfer of heat, understanding them is

crucial to global climate modeling, says Tom

15 Peacock, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. Most models fail to take internal

waves into account. “If we want to have more and

more accurate climate models, we have to be able to

capture processes such as this,” Peacock says.

20 Peacock and his colleagues tried to do just that.

Their study, published in November in Geophysical

Research Letters, focused on internal waves generated

in the Luzon Strait, which separates Taiwan and the

Philippines. Internal waves in this region, thought to

25 be some of the largest in the world, can reach about

500 meters high. “That’s the same height as the

Freedom Tower that’s just been built in New York,”

Peacock says.

Although scientists knew of this phenomenon in

30 the South China Sea and beyond, they didn’t know

exactly how internal waves formed. To find out,

Peacock and a team of researchers from M.I.T. and

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worked with

France’s National Center for Scientific Research

35 using a giant facility there called the Coriolis

Platform. The rotating platform, about 15 meters

(49.2 feet) in diameter, turns at variable speeds and

can simulate Earth’s rotation. It also has walls, which

means scientists can fill it with water and create

40 accurate, large-scale simulations of various

oceanographic scenarios.

Peacock and his team built a carbon-fiber resin

scale model of the Luzon Strait, including the islands

and surrounding ocean floor topography. Then they

45 filled the platform with water of varying salinity to

replicate the different densities found at the strait,

with denser, saltier water below and lighter, less

briny water above. Small particles were added to the

solution and illuminated with lights from below in

50 order to track how the liquid moved. Finally, they

re-created tides using two large plungers to see how

the internal waves themselves formed.

The Luzon Strait’s underwater topography, with a

distinct double-ridge shape, turns out to be

55 responsible for generating the underwater waves.

As the tide rises and falls and water moves through

the strait, colder, denser water is pushed up over the

ridges into warmer, less dense layers above it.

This action results in bumps of colder water trailed

60 by warmer water that generate an internal wave.

As these waves move toward land, they become

steeper—much the same way waves at the beach

become taller before they hit the shore—until they

break on a continental shelf.

65 The researchers were also able to devise a

mathematical model that describes the movement

and formation of these waves. Whereas the model is

specific to the Luzon Strait, it can still help

researchers understand how internal waves are

70 generated in other places around the world.

Eventually, this information will be incorporated into

global climate models, making them more accurate.

“It’s very clear, within the context of these [global

climate] models, that internal waves play a role in

75 driving ocean circulations,” Peacock says.

Q. As used in line 65, “devise” most nearly means

Question is based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Geoffrey Giller, “Long a Mystery, How 500-Meter-High Undersea Waves Form Is Revealed.” ©2014 by Scientific American.

Some of the largest ocean waves in the world are

nearly impossible to see. Unlike other large waves,

these rollers, called internal waves, do not ride the

ocean surface. Instead, they move underwater,

5 undetectable without the use of satellite imagery or

sophisticated monitoring equipment. Despite their

hidden nature, internal waves are fundamental parts

of ocean water dynamics, transferring heat to the

ocean depths and bringing up cold water from below.

10 And they can reach staggering heights—some as tall

as skyscrapers.

Because these waves are involved in ocean mixing