CAT 2021 Slot 2: Past Year Question Paper - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test CAT Mock Test Series 2024 - CAT 2021 Slot 2: Past Year Question Paper

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

Q. The author discusses all of the following arguments in the passage, EXCEPT:

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

Q. “. . . we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it . . .” Which one of the following statements best reflects the argument being made in this sentence?

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

Q. According to the last paragraph of the passage, “We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on” something. Which one of the following most broadly captures what we depend on?

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It has been said that knowledge, or the problem of knowledge, is the scandal of philosophy. The scandal is philosophy’s apparent inability to show how, when and why we can be sure that we know something or, indeed, that we know anything. Philosopher Michael Williams writes: ‘Is it possible to obtain knowledge at all? This problem is pressing because there are powerful arguments, some very ancient, for the conclusion that it is not . . . Scepticism is the skeleton in Western rationalism’s closet’. While it is not clear that the scandal matters to anyone but philosophers, philosophers point out that it should matter to everyone, at least given a certain conception of knowledge. For, they explain, unless we can ground our claims to knowledge as such, which is to say, distinguish it from mere opinion, superstition, fantasy, wishful thinking, ideology, illusion or delusion, then the actions we take on the basis of presumed knowledge - boarding an airplane, swallowing a pill, finding someone guilty of a crime - will be irrational and unjustifiable.

That is all quite serious-sounding but so also are the rattlings of the skeleton: that is, the sceptic’s contention that we cannot be sure that we know anything - at least not if we think of knowledge as something like having a correct mental representation of reality, and not if we think of reality as something like things-as-they-are-in-themselves, independent of our perceptions, ideas or descriptions. For, the sceptic will note, since reality, under that conception of it, is outside our ken (we cannot catch a glimpse of things-in-themselves around the corner of our own eyes; we cannot form an idea of reality that floats above the processes of our conceiving it), we have no way to compare our mental representations with things-as-they-are-in-themselves and therefore no way to determine whether they are correct or incorrect. Thus the sceptic may repeat (rattling loudly), you cannot be sure you ‘know’ something or anything at all - at least not, he may add (rattling softly before disappearing), if that is the way you conceive ‘knowledge’.

There are a number of ways to handle this situation. The most common is to ignore it. Most people outside the academy - and, indeed, most of us inside it - are unaware of or unperturbed by the philosophical scandal of knowledge and go about our lives without too many epistemic anxieties. We hold our beliefs and presumptive knowledges more or less confidently, usually depending on how we acquired them (I saw it with my own eyes; I heard it on Fox News; a guy at the office told me) and how broadly and strenuously they seem to be shared or endorsed by various relevant people: experts and authorities, friends and family members, colleagues and associates. And we examine our convictions more or less closely, explain them more or less extensively, and defend them more or less vigorously, usually depending on what seems to be at stake for ourselves and/or other people and what resources are available for reassuring ourselves or making our beliefs credible to others (look, it’s right here on the page; add up the figures yourself; I happen to be a heart specialist).

Q. The author of the passage is most likely to support which one of the following statements?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It’s easy to forget that most of the world’s languages are still transmitted orally with no widely established written form. While speech communities are increasingly involved in projects to protect their languages - in print, on air and online - orality is fragile and contributes to linguistic vulnerability. But indigenous languages are about much more than unusual words and intriguing grammar: They function as vehicles for the transmission of cultural traditions, environmental understandings and knowledge about medicinal plants, all at risk when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted.

Both push and pull factors lead to the decline of languages. Through war, famine and natural disasters, whole communities can be destroyed, taking their language with them to the grave, such as the indigenous populations of Tasmania who were wiped out by colonists. More commonly, speakers live on but abandon their language in favor of another vernacular, a widespread process that linguists refer to as “language shift” from which few languages are immune. Such trading up and out of a speech form occurs for complex political, cultural and economic reasons - sometimes voluntary for economic and educational reasons, although often amplified by state coercion or neglect. Welsh, long stigmatized and disparaged by the British state, has rebounded with vigor.

Many speakers of endangered, poorly documented languages have embraced new digital media with excitement. Speakers of previously exclusively oral tongues are turning to the web as a virtual space for languages to live on. Internet technology offers powerful ways for oral traditions and cultural practices to survive, even thrive, among increasingly mobile communities. I have watched as videos of traditional wedding ceremonies and songs are recorded on smartphones in London by Nepali migrants, then uploaded to YouTube and watched an hour later by relatives in remote Himalayan villages . . .

Globalization is regularly, and often uncritically, pilloried as a major threat to linguistic diversity. But in fact, globalization is as much process as it is ideology, certainly when it comes to language. The real forces behind cultural homogenization are unbending beliefs, exchanged through a globalized delivery system, reinforced by the historical monolingualism prevalent in much of the West.

Monolingualism - the condition of being able to speak only one language - is regularly accompanied by a deep-seated conviction in the value of that language over all others. Across the largest economies that make up the G8, being monolingual is still often the norm, with multilingualism appearing unusual and even somewhat exotic. The monolingual mindset stands in sharp contrast to the lived reality of most the world, which throughout its history has been more multilingual than unilingual. Monolingualism, then, not globalization, should be our primary concern.

Multilingualism can help us live in a more connected and more interdependent world. By widening access to technology, globalization can support indigenous and scholarly communities engaged in documenting and protecting our shared linguistic heritage. For the last 5,000 years, the rise and fall of languages was intimately tied to the plow, sword and book. In our digital age, the keyboard, screen and web will play a decisive role in shaping the future linguistic diversity of our species.

Q. The author lists all of the following as reasons for the decline or disappearance of a language EXCEPT:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It’s easy to forget that most of the world’s languages are still transmitted orally with no widely established written form. While speech communities are increasingly involved in projects to protect their languages - in print, on air and online - orality is fragile and contributes to linguistic vulnerability. But indigenous languages are about much more than unusual words and intriguing grammar: They function as vehicles for the transmission of cultural traditions, environmental understandings and knowledge about medicinal plants, all at risk when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted.

Both push and pull factors lead to the decline of languages. Through war, famine and natural disasters, whole communities can be destroyed, taking their language with them to the grave, such as the indigenous populations of Tasmania who were wiped out by colonists. More commonly, speakers live on but abandon their language in favor of another vernacular, a widespread process that linguists refer to as “language shift” from which few languages are immune. Such trading up and out of a speech form occurs for complex political, cultural and economic reasons - sometimes voluntary for economic and educational reasons, although often amplified by state coercion or neglect. Welsh, long stigmatized and disparaged by the British state, has rebounded with vigor.

Many speakers of endangered, poorly documented languages have embraced new digital media with excitement. Speakers of previously exclusively oral tongues are turning to the web as a virtual space for languages to live on. Internet technology offers powerful ways for oral traditions and cultural practices to survive, even thrive, among increasingly mobile communities. I have watched as videos of traditional wedding ceremonies and songs are recorded on smartphones in London by Nepali migrants, then uploaded to YouTube and watched an hour later by relatives in remote Himalayan villages . . .

Globalization is regularly, and often uncritically, pilloried as a major threat to linguistic diversity. But in fact, globalization is as much process as it is ideology, certainly when it comes to language. The real forces behind cultural homogenization are unbending beliefs, exchanged through a globalized delivery system, reinforced by the historical monolingualism prevalent in much of the West.

Monolingualism - the condition of being able to speak only one language - is regularly accompanied by a deep-seated conviction in the value of that language over all others. Across the largest economies that make up the G8, being monolingual is still often the norm, with multilingualism appearing unusual and even somewhat exotic. The monolingual mindset stands in sharp contrast to the lived reality of most the world, which throughout its history has been more multilingual than unilingual. Monolingualism, then, not globalization, should be our primary concern.

Multilingualism can help us live in a more connected and more interdependent world. By widening access to technology, globalization can support indigenous and scholarly communities engaged in documenting and protecting our shared linguistic heritage. For the last 5,000 years, the rise and fall of languages was intimately tied to the plow, sword and book. In our digital age, the keyboard, screen and web will play a decisive role in shaping the future linguistic diversity of our species.

Q. We can infer all of the following about indigenous languages from the passage EXCEPT that:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It’s easy to forget that most of the world’s languages are still transmitted orally with no widely established written form. While speech communities are increasingly involved in projects to protect their languages - in print, on air and online - orality is fragile and contributes to linguistic vulnerability. But indigenous languages are about much more than unusual words and intriguing grammar: They function as vehicles for the transmission of cultural traditions, environmental understandings and knowledge about medicinal plants, all at risk when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted.

Both push and pull factors lead to the decline of languages. Through war, famine and natural disasters, whole communities can be destroyed, taking their language with them to the grave, such as the indigenous populations of Tasmania who were wiped out by colonists. More commonly, speakers live on but abandon their language in favor of another vernacular, a widespread process that linguists refer to as “language shift” from which few languages are immune. Such trading up and out of a speech form occurs for complex political, cultural and economic reasons - sometimes voluntary for economic and educational reasons, although often amplified by state coercion or neglect. Welsh, long stigmatized and disparaged by the British state, has rebounded with vigor.

Many speakers of endangered, poorly documented languages have embraced new digital media with excitement. Speakers of previously exclusively oral tongues are turning to the web as a virtual space for languages to live on. Internet technology offers powerful ways for oral traditions and cultural practices to survive, even thrive, among increasingly mobile communities. I have watched as videos of traditional wedding ceremonies and songs are recorded on smartphones in London by Nepali migrants, then uploaded to YouTube and watched an hour later by relatives in remote Himalayan villages . . .

Globalization is regularly, and often uncritically, pilloried as a major threat to linguistic diversity. But in fact, globalization is as much process as it is ideology, certainly when it comes to language. The real forces behind cultural homogenization are unbending beliefs, exchanged through a globalized delivery system, reinforced by the historical monolingualism prevalent in much of the West.

Monolingualism - the condition of being able to speak only one language - is regularly accompanied by a deep-seated conviction in the value of that language over all others. Across the largest economies that make up the G8, being monolingual is still often the norm, with multilingualism appearing unusual and even somewhat exotic. The monolingual mindset stands in sharp contrast to the lived reality of most the world, which throughout its history has been more multilingual than unilingual. Monolingualism, then, not globalization, should be our primary concern.

Multilingualism can help us live in a more connected and more interdependent world. By widening access to technology, globalization can support indigenous and scholarly communities engaged in documenting and protecting our shared linguistic heritage. For the last 5,000 years, the rise and fall of languages was intimately tied to the plow, sword and book. In our digital age, the keyboard, screen and web will play a decisive role in shaping the future linguistic diversity of our species.

Q. From the passage, we can infer that the author is in favour of:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

It’s easy to forget that most of the world’s languages are still transmitted orally with no widely established written form. While speech communities are increasingly involved in projects to protect their languages - in print, on air and online - orality is fragile and contributes to linguistic vulnerability. But indigenous languages are about much more than unusual words and intriguing grammar: They function as vehicles for the transmission of cultural traditions, environmental understandings and knowledge about medicinal plants, all at risk when elders die and livelihoods are disrupted.

Both push and pull factors lead to the decline of languages. Through war, famine and natural disasters, whole communities can be destroyed, taking their language with them to the grave, such as the indigenous populations of Tasmania who were wiped out by colonists. More commonly, speakers live on but abandon their language in favor of another vernacular, a widespread process that linguists refer to as “language shift” from which few languages are immune. Such trading up and out of a speech form occurs for complex political, cultural and economic reasons - sometimes voluntary for economic and educational reasons, although often amplified by state coercion or neglect. Welsh, long stigmatized and disparaged by the British state, has rebounded with vigor.

Many speakers of endangered, poorly documented languages have embraced new digital media with excitement. Speakers of previously exclusively oral tongues are turning to the web as a virtual space for languages to live on. Internet technology offers powerful ways for oral traditions and cultural practices to survive, even thrive, among increasingly mobile communities. I have watched as videos of traditional wedding ceremonies and songs are recorded on smartphones in London by Nepali migrants, then uploaded to YouTube and watched an hour later by relatives in remote Himalayan villages . . .

Globalization is regularly, and often uncritically, pilloried as a major threat to linguistic diversity. But in fact, globalization is as much process as it is ideology, certainly when it comes to language. The real forces behind cultural homogenization are unbending beliefs, exchanged through a globalized delivery system, reinforced by the historical monolingualism prevalent in much of the West.

Monolingualism - the condition of being able to speak only one language - is regularly accompanied by a deep-seated conviction in the value of that language over all others. Across the largest economies that make up the G8, being monolingual is still often the norm, with multilingualism appearing unusual and even somewhat exotic. The monolingual mindset stands in sharp contrast to the lived reality of most the world, which throughout its history has been more multilingual than unilingual. Monolingualism, then, not globalization, should be our primary concern.

Multilingualism can help us live in a more connected and more interdependent world. By widening access to technology, globalization can support indigenous and scholarly communities engaged in documenting and protecting our shared linguistic heritage. For the last 5,000 years, the rise and fall of languages was intimately tied to the plow, sword and book. In our digital age, the keyboard, screen and web will play a decisive role in shaping the future linguistic diversity of our species.

Q. The author mentions the Welsh language to show that:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

I have elaborated . . . a framework for analyzing the contradictory pulls on [Indian] nationalist ideology in its struggle against the dominance of colonialism and the resolution it offered to those contradictions. Briefly, this resolution was built around a separation of the domain of culture into two spheres—the material and the spiritual. It was in the material sphere that the claims of Western civilization were the most powerful. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people . . . To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. . . . But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. . . .

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. . . . Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bāhir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one’s inner spiritual self, one’s true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bāhir. . . .

The colonial situation, and the ideological response of nationalism to the critique of Indian tradition, introduced an entirely new substance to [these dichotomies] and effected their transformation. The material/spiritual dichotomy, to which the terms world and home corresponded, had acquired . . . a very special significance in the nationalist mind. The world was where the European power had challenged the non-European people and, by virtue of its superior material culture, had subjugated them. But, the nationalists asserted, it had failed to colonize the inner, essential, identity of the East which lay in its distinctive, and superior, spiritual culture. . . . [I]n the entire phase of the national struggle, the crucial need was to protect, preserve and strengthen the inner core of the national culture, its spiritual essence. . . .

Once we match this new meaning of the home/world dichotomy with the identification of social roles by gender, we get the ideological framework within which nationalism answered the women’s question. It would be a grave error to see in this, as liberals are apt to in their despair at the many marks of social conservatism in nationalist practice, a total rejection of the West. Quite the contrary: the nationalist paradigm in fact supplied an ideological principle of selection.

Q. Which one of the following explains the “contradictory pulls” on Indian nationalism?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

I have elaborated . . . a framework for analyzing the contradictory pulls on [Indian] nationalist ideology in its struggle against the dominance of colonialism and the resolution it offered to those contradictions. Briefly, this resolution was built around a separation of the domain of culture into two spheres—the material and the spiritual. It was in the material sphere that the claims of Western civilization were the most powerful. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people . . . To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. . . . But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. . . .

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. . . . Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bāhir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one’s inner spiritual self, one’s true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bāhir. . . .

The colonial situation, and the ideological response of nationalism to the critique of Indian tradition, introduced an entirely new substance to [these dichotomies] and effected their transformation. The material/spiritual dichotomy, to which the terms world and home corresponded, had acquired . . . a very special significance in the nationalist mind. The world was where the European power had challenged the non-European people and, by virtue of its superior material culture, had subjugated them. But, the nationalists asserted, it had failed to colonize the inner, essential, identity of the East which lay in its distinctive, and superior, spiritual culture. . . . [I]n the entire phase of the national struggle, the crucial need was to protect, preserve and strengthen the inner core of the national culture, its spiritual essence. . . .

Once we match this new meaning of the home/world dichotomy with the identification of social roles by gender, we get the ideological framework within which nationalism answered the women’s question. It would be a grave error to see in this, as liberals are apt to in their despair at the many marks of social conservatism in nationalist practice, a total rejection of the West. Quite the contrary: the nationalist paradigm in fact supplied an ideological principle of selection.

Q. On the basis of the information in the passage, all of the following are true about the spiritual/material dichotomy of Indian nationalism EXCEPT that it:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

I have elaborated . . . a framework for analyzing the contradictory pulls on [Indian] nationalist ideology in its struggle against the dominance of colonialism and the resolution it offered to those contradictions. Briefly, this resolution was built around a separation of the domain of culture into two spheres—the material and the spiritual. It was in the material sphere that the claims of Western civilization were the most powerful. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people . . . To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. . . . But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. . . .

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. . . . Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bāhir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one’s inner spiritual self, one’s true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bāhir. . . .

The colonial situation, and the ideological response of nationalism to the critique of Indian tradition, introduced an entirely new substance to [these dichotomies] and effected their transformation. The material/spiritual dichotomy, to which the terms world and home corresponded, had acquired . . . a very special significance in the nationalist mind. The world was where the European power had challenged the non-European people and, by virtue of its superior material culture, had subjugated them. But, the nationalists asserted, it had failed to colonize the inner, essential, identity of the East which lay in its distinctive, and superior, spiritual culture. . . . [I]n the entire phase of the national struggle, the crucial need was to protect, preserve and strengthen the inner core of the national culture, its spiritual essence. . . .

Once we match this new meaning of the home/world dichotomy with the identification of social roles by gender, we get the ideological framework within which nationalism answered the women’s question. It would be a grave error to see in this, as liberals are apt to in their despair at the many marks of social conservatism in nationalist practice, a total rejection of the West. Quite the contrary: the nationalist paradigm in fact supplied an ideological principle of selection.

Q. Which one of the following, if true, would weaken the author’s claims in the passage?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

I have elaborated . . . a framework for analyzing the contradictory pulls on [Indian] nationalist ideology in its struggle against the dominance of colonialism and the resolution it offered to those contradictions. Briefly, this resolution was built around a separation of the domain of culture into two spheres—the material and the spiritual. It was in the material sphere that the claims of Western civilization were the most powerful. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people . . . To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. . . . But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. . . .

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. . . . Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bāhir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one’s inner spiritual self, one’s true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bāhir. . . .

The colonial situation, and the ideological response of nationalism to the critique of Indian tradition, introduced an entirely new substance to [these dichotomies] and effected their transformation. The material/spiritual dichotomy, to which the terms world and home corresponded, had acquired . . . a very special significance in the nationalist mind. The world was where the European power had challenged the non-European people and, by virtue of its superior material culture, had subjugated them. But, the nationalists asserted, it had failed to colonize the inner, essential, identity of the East which lay in its distinctive, and superior, spiritual culture. . . . [I]n the entire phase of the national struggle, the crucial need was to protect, preserve and strengthen the inner core of the national culture, its spiritual essence. . . .

Once we match this new meaning of the home/world dichotomy with the identification of social roles by gender, we get the ideological framework within which nationalism answered the women’s question. It would be a grave error to see in this, as liberals are apt to in their despair at the many marks of social conservatism in nationalist practice, a total rejection of the West. Quite the contrary: the nationalist paradigm in fact supplied an ideological principle of selection.

Q. Which one of the following best describes the liberal perception of Indian nationalism?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Many people believe that truth conveys power. . . . Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things.

On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb. On the other hand, power also means having the ability to manipulate human beliefs, thereby getting lots of people to cooperate effectively. Building atom bombs requires not just a good understanding of physics, but also the coordinated labor of millions of humans.

Planet Earth was conquered by Homo sapiens rather than by chimpanzees or elephants, because we are the only mammals that can cooperate in very large numbers. And large-scale cooperation depends on believing common stories. But these stories need not be true.

You can unite millions of people by making them believe in completely fictional stories about God, about race or about economics. The dual nature of power and truth results in the curious fact that we humans know many more truths than any other animal, but we also believe in much more nonsense. . . .

When it comes to uniting people around a common story, fiction actually enjoys three inherent advantages over the truth. First, whereas the truth is universal, fictions tend to be local. Consequently if we want to distinguish our tribe from foreigners, a fictional story will serve as a far better identity marker than a true story. . . . The second huge advantage of fiction over truth has to do with the handicap principle, which says that reliable signals must be costly to the signaler. Otherwise, they can easily be faked by cheaters. . . . If political loyalty is signaled by believing a true story, anyone can fake it. But believing ridiculous and outlandish stories exacts greater cost, and is therefore a better signal of loyalty. . . . Third, and most important, the truth is often painful and disturbing. Hence if you stick to unalloyed reality, few people will follow you. An American presidential candidate who tells the American public the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about American history has a 100 percent guarantee of losing the elections. . . . An uncompromising adherence to the truth is an admirable spiritual practice, but it is not a winning political strategy. . . .

Even if we need to pay some price for deactivating our rational faculties, the advantages of increased social cohesion are often so big that fictional stories routinely triumph over the truth in human history. Scholars have known this for thousands of years, which is why scholars often had to decide whether they served the truth or social harmony. Should they aim to unite people by making sure everyone believes in the same fiction, or should they let people know the truth even at the price of disunity?

Q. The central theme of the passage is about the choice between:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Many people believe that truth conveys power. . . . Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things.

On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb. On the other hand, power also means having the ability to manipulate human beliefs, thereby getting lots of people to cooperate effectively. Building atom bombs requires not just a good understanding of physics, but also the coordinated labor of millions of humans.

Planet Earth was conquered by Homo sapiens rather than by chimpanzees or elephants, because we are the only mammals that can cooperate in very large numbers. And large-scale cooperation depends on believing common stories. But these stories need not be true.

You can unite millions of people by making them believe in completely fictional stories about God, about race or about economics. The dual nature of power and truth results in the curious fact that we humans know many more truths than any other animal, but we also believe in much more nonsense. . . .

When it comes to uniting people around a common story, fiction actually enjoys three inherent advantages over the truth. First, whereas the truth is universal, fictions tend to be local. Consequently if we want to distinguish our tribe from foreigners, a fictional story will serve as a far better identity marker than a true story. . . . The second huge advantage of fiction over truth has to do with the handicap principle, which says that reliable signals must be costly to the signaler. Otherwise, they can easily be faked by cheaters. . . . If political loyalty is signaled by believing a true story, anyone can fake it. But believing ridiculous and outlandish stories exacts greater cost, and is therefore a better signal of loyalty. . . . Third, and most important, the truth is often painful and disturbing. Hence if you stick to unalloyed reality, few people will follow you. An American presidential candidate who tells the American public the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about American history has a 100 percent guarantee of losing the elections. . . . An uncompromising adherence to the truth is an admirable spiritual practice, but it is not a winning political strategy. . . .

Even if we need to pay some price for deactivating our rational faculties, the advantages of increased social cohesion are often so big that fictional stories routinely triumph over the truth in human history. Scholars have known this for thousands of years, which is why scholars often had to decide whether they served the truth or social harmony. Should they aim to unite people by making sure everyone believes in the same fiction, or should they let people know the truth even at the price of disunity?

Q. The author would support none of the following statements about political power EXCEPT that:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Many people believe that truth conveys power. . . . Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things.

On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb. On the other hand, power also means having the ability to manipulate human beliefs, thereby getting lots of people to cooperate effectively. Building atom bombs requires not just a good understanding of physics, but also the coordinated labor of millions of humans.

Planet Earth was conquered by Homo sapiens rather than by chimpanzees or elephants, because we are the only mammals that can cooperate in very large numbers. And large-scale cooperation depends on believing common stories. But these stories need not be true.

You can unite millions of people by making them believe in completely fictional stories about God, about race or about economics. The dual nature of power and truth results in the curious fact that we humans know many more truths than any other animal, but we also believe in much more nonsense. . . .

When it comes to uniting people around a common story, fiction actually enjoys three inherent advantages over the truth. First, whereas the truth is universal, fictions tend to be local. Consequently if we want to distinguish our tribe from foreigners, a fictional story will serve as a far better identity marker than a true story. . . . The second huge advantage of fiction over truth has to do with the handicap principle, which says that reliable signals must be costly to the signaler. Otherwise, they can easily be faked by cheaters. . . . If political loyalty is signaled by believing a true story, anyone can fake it. But believing ridiculous and outlandish stories exacts greater cost, and is therefore a better signal of loyalty. . . . Third, and most important, the truth is often painful and disturbing. Hence if you stick to unalloyed reality, few people will follow you. An American presidential candidate who tells the American public the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about American history has a 100 percent guarantee of losing the elections. . . . An uncompromising adherence to the truth is an admirable spiritual practice, but it is not a winning political strategy. . . .

Even if we need to pay some price for deactivating our rational faculties, the advantages of increased social cohesion are often so big that fictional stories routinely triumph over the truth in human history. Scholars have known this for thousands of years, which is why scholars often had to decide whether they served the truth or social harmony. Should they aim to unite people by making sure everyone believes in the same fiction, or should they let people know the truth even at the price of disunity?

Q. The author implies that, like scholars, successful leaders:

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Many people believe that truth conveys power. . . . Hence sticking with the truth is the best strategy for gaining power. Unfortunately, this is just a comforting myth. In fact, truth and power have a far more complicated relationship, because in human society, power means two very different things.

On the one hand, power means having the ability to manipulate objective realities: to hunt animals, to construct bridges, to cure diseases, to build atom bombs. This kind of power is closely tied to truth. If you believe a false physical theory, you won’t be able to build an atom bomb. On the other hand, power also means having the ability to manipulate human beliefs, thereby getting lots of people to cooperate effectively. Building atom bombs requires not just a good understanding of physics, but also the coordinated labor of millions of humans.

Planet Earth was conquered by Homo sapiens rather than by chimpanzees or elephants, because we are the only mammals that can cooperate in very large numbers. And large-scale cooperation depends on believing common stories. But these stories need not be true.

You can unite millions of people by making them believe in completely fictional stories about God, about race or about economics. The dual nature of power and truth results in the curious fact that we humans know many more truths than any other animal, but we also believe in much more nonsense. . . .

When it comes to uniting people around a common story, fiction actually enjoys three inherent advantages over the truth. First, whereas the truth is universal, fictions tend to be local. Consequently if we want to distinguish our tribe from foreigners, a fictional story will serve as a far better identity marker than a true story. . . . The second huge advantage of fiction over truth has to do with the handicap principle, which says that reliable signals must be costly to the signaler. Otherwise, they can easily be faked by cheaters. . . . If political loyalty is signaled by believing a true story, anyone can fake it. But believing ridiculous and outlandish stories exacts greater cost, and is therefore a better signal of loyalty. . . . Third, and most important, the truth is often painful and disturbing. Hence if you stick to unalloyed reality, few people will follow you. An American presidential candidate who tells the American public the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about American history has a 100 percent guarantee of losing the elections. . . . An uncompromising adherence to the truth is an admirable spiritual practice, but it is not a winning political strategy. . . .

Even if we need to pay some price for deactivating our rational faculties, the advantages of increased social cohesion are often so big that fictional stories routinely triumph over the truth in human history. Scholars have known this for thousands of years, which is why scholars often had to decide whether they served the truth or social harmony. Should they aim to unite people by making sure everyone believes in the same fiction, or should they let people know the truth even at the price of disunity?

Q. Regarding which one of the following quotes could we argue that the author overemphasises the importance of fiction?

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Biologists who publish their research directly to the Web have been labelled as “rogue”, but physicists have been routinely publishing research digitally (“preprints”), prior to submitting in a peer-reviewed journal. Advocates of preprints argue that quick and open dissemination of research speeds up scientific progress and allows for wider access to knowledge. But some journals still don’t accept research previously published as a preprint. Even if the idea of preprints is gaining ground, one of the biggest barriers for biologists is how they would be viewed by members of their conservative research community.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- But today there is an epochal challenge to rethink and reconstitute the vision and practice of development as a shared responsibility - a sharing which binds both the agent and the audience, the developed world and the developing, in a bond of shared destiny.

- We are at a crossroads now in our vision and practice of development.

- This calls for the cultivation of an appropriate ethical mode of being in our lives which enables us to realize this global and planetary situation of shared living and responsibility.

- Half a century ago, development began as a hope for a better human possibility, but in the last fifty years, this hope has lost itself in the dreary desert of various kinds of hegemonic applications.

Five jumbled up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer:

- The care with which philosophers examine arguments for and against forms of biotechnology makes this an excellent primer on formulating and assessing moral arguments.

- Although most people find at least some forms of genetic engineering disquieting, it is not easy to articulate why: what is wrong with re-engineering our nature?

- Breakthroughs in genetics present us with the promise that we will soon be able to prevent a host of debilitating diseases, and the predicament that our newfound genetic knowledge may enable us to enhance our genetic traits.

- To grapple with the ethics of enhancement, we need to confront questions that verge on theology, which is why modern philosophers and political theorists tend to shrink from them.

- One argument is that the drive for human perfection through genetics is objectionable as it represents a bid for mastery that fails to appreciate the gifts of human powers and achievements.

Five jumbled up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer:

- It has taken on a warm, fuzzy glow in the advertising world, where its potential is being widely discussed, and it is being claimed as the undeniable wave of the future.

- There is little enthusiasm for this in the scientific arena; for them marketing is not a science, and only a handful of studies have been published in scientific journals.

- The new, growing field of neuromarketing attempts to reveal the inner workings of consumer behaviour and is an extension of the study of how choices and decisions are made.

- Some see neuromarketing as an attempt to make the "art" of advertising into a science, being used by marketing experts to back up their proposals with some form of real data.

- The marketing gurus have already started drawing on psychology in developing tests and theories, and advertising people have borrowed the idea of the focus group from social scientists.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3 and 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- Look forward a few decades to an invention which can end the energy crisis, change the global economy and curb climate change at a stroke: commercial fusion power.

- To gain meaningful insights, logic has to be accompanied by asking probing questions of nature through controlled tests, precise observations and clever analysis.

- The greatest of all inventions is the über-invention that has provided the insights on which others depend: the modern scientific method.

- This invention is inconceivable without the scientific method; it will rest on the application of a diverse range of scientific insights, such as the process transforming hydrogen into helium to release huge amounts of energy.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Creativity is now viewed as the engine of economic progress. Various organizations are devoted to its study and promotion; there are encyclopedias and handbooks surveying creativity research. But this proliferating success has tended to erode creativity’s stable identity: it has become so invested with value that it has become impossible to police its meaning and the practices that supposedly identify and encourage it. Many people and organizations committed to producing original thoughts now feel that undue obsession with the idea of creativity gets in the way of real creativity.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3 and 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- The US has long maintained that the Northwest Passage is an international strait through which its commercial and military vessels have the right to pass without seeking Canada’s permission.

- Canada, which officially acquired the group of islands forming the Northwest Passage in 1880, claims sovereignty over all the shipping routes through the Passage.

- The dispute could be transitory, however, as scientists speculate that the entire Arctic Ocean will soon be ice-free in summer, so ship owners will not have to ask for permission to sail through any of the Northwest Passage routes.

- The US and Canada have never legally settled the question of access through the Passage, but have an agreement whereby the US needs to seek Canada’s consent for any transit.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

The unlikely alliance of the incumbent industrialist and the distressed unemployed worker is especially powerful amid the debris of corporate bankruptcies and layoffs. In an economic downturn, the capitalist is more likely to focus on costs of the competition emanating from free markets than on the opportunities they create. And the unemployed worker will find many others in a similar condition and with anxieties similar to his, which will make it easier for them to organize together. Using the cover and the political organization provided by the distressed, the capitalist captures the political agenda.

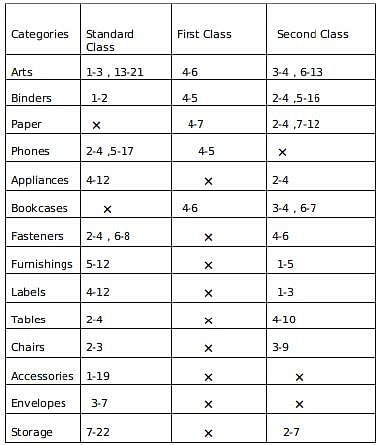

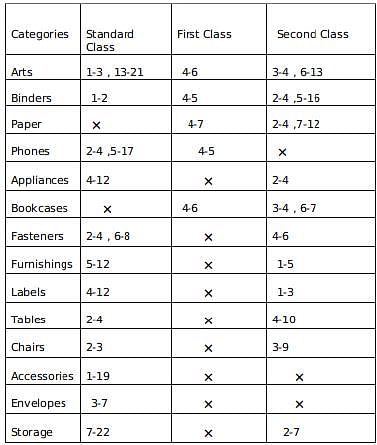

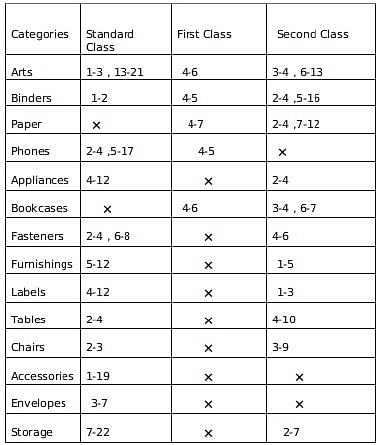

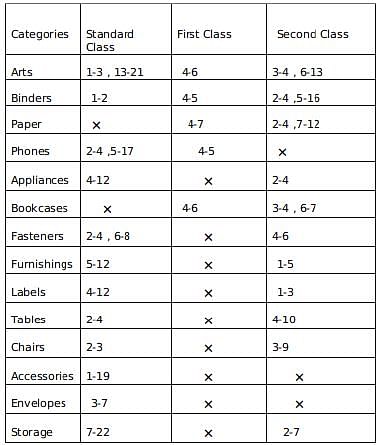

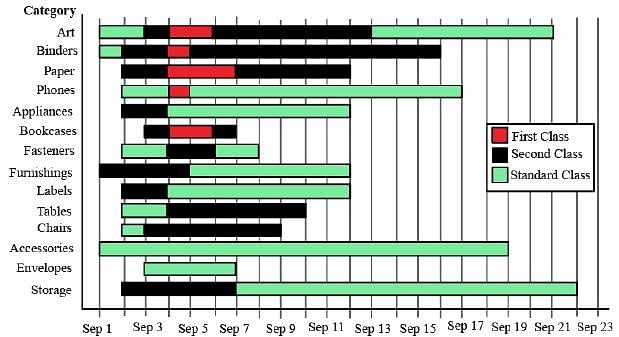

The different bars in the diagram above provide information about different orders in various categories (Art, Binders, ….) that were booked in the first two weeks of September of a store for one client. The colour and pattern of a bar denotes the ship mode (First Class / Second Class / Standard Class). The left end point of a bar indicates the booking day of the order, while the right end point indicates the dispatch day of the order. The difference between the dispatch day and the booking day (measured in terms of the number of days) is called the processing time of the order. For the same category, an order is considered for booking only after the previous order of the same category is dispatched. No two consecutive orders of the same category had identical ship mode during this period.

For example, there were only two orders in the furnishing category during this period. The first one was shipped in the Second Class. It was booked on Sep 1 and dispatched on Sep 5. The second order was shipped in the Standard class. It was booked on Sep 5 (although the order might have been placed before that) and dispatched on Sep 12. So the processing times were 4 and 7 days respectively for these orders.

Q. How many days between Sep 1 and Sep 14 (both inclusive) had no booking from this client considering all the above categories?

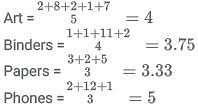

What was the average processing time of all orders in the categories which had only one type of ship mode?

The sequence of categories -- Art, Binders, Paper and Phones -- in decreasing order of average processing time of their orders in this period is:

Approximately what percentage of orders had a processing time of one day during the period Sep 1 to Sep 22 (both dates inclusive)?

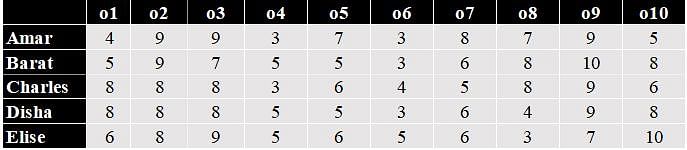

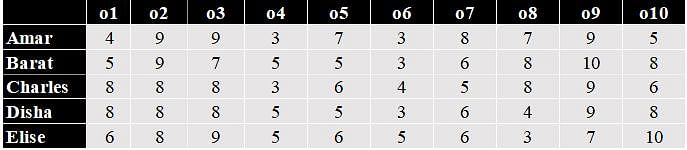

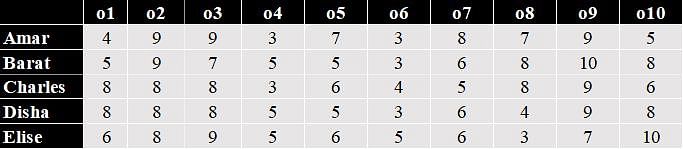

Ten objects o1, o2, …, o10 were distributed among Amar, Barat, Charles, Disha, and Elise. Each item went to exactly one person. Each person got exactly two of the items, and this pair of objects is called her/his bundle.

The following table shows how each person values each object.

The value of any bundle by a person is the sum of that person’s values of the objects in that bundle. A person X envies another person Y if X values Y’s bundle more than X’s own bundle.

For example, hypothetically suppose Amar’s bundle consists of o1 and o2, and Barat’s bundle consists of o3 and o4. Then Amar values his own bundle at 4 + 9 = 13 and Barat’s bundle at 9 + 3 = 12. Hence Amar does not envy Barat. On the other hand, Barat values his own bundle at 7 + 5 = 12 and Amar’s bundle at 5 + 9 = 14. Hence Barat envies Amar.

The following facts are known about the actual distribution of the objects among the five people.

- If someone’s value for an object is 10, then she/he received that object.

- Objects o1, o2, and o3 were given to three different people.

- Objects o1 and o8 were given to different people.

- Three people value their own bundles at 16. No one values her/his own bundle at a number higher than 16.

- Disha values her own bundle at an odd number. All others value their own bundles at an even number.

- Some people who value their own bundles less than 16 envy some other people who value their own bundle at 16. No one else envies others.

Q. What BEST can be said about object o8?

Ten objects o1, o2, …, o10 were distributed among Amar, Barat, Charles, Disha, and Elise. Each item went to exactly one person. Each person got exactly two of the items, and this pair of objects is called her/his bundle.

The following table shows how each person values each object.

The value of any bundle by a person is the sum of that person’s values of the objects in that bundle. A person X envies another person Y if X values Y’s bundle more than X’s own bundle.

For example, hypothetically suppose Amar’s bundle consists of o1 and o2, and Barat’s bundle consists of o3 and o4. Then Amar values his own bundle at 4 + 9 = 13 and Barat’s bundle at 9 + 3 = 12. Hence Amar does not envy Barat. On the other hand, Barat values his own bundle at 7 + 5 = 12 and Amar’s bundle at 5 + 9 = 14. Hence Barat envies Amar.

The following facts are known about the actual distribution of the objects among the five people.

- If someone’s value for an object is 10, then she/he received that object.

- Objects o1, o2, and o3 were given to three different people.

- Objects o1 and o8 were given to different people.

- Three people value their own bundles at 16. No one values her/his own bundle at a number higher than 16.

- Disha values her own bundle at an odd number. All others value their own bundles at an even number.

- Some people who value their own bundles less than 16 envy some other people who value their own bundle at 16. No one else envies others.

Q. Who among the following envies someone else?

|

16 videos|27 docs|58 tests

|

|

16 videos|27 docs|58 tests

|