Class 9 History Chapter 2 Notes - Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution

The Age of Social Change

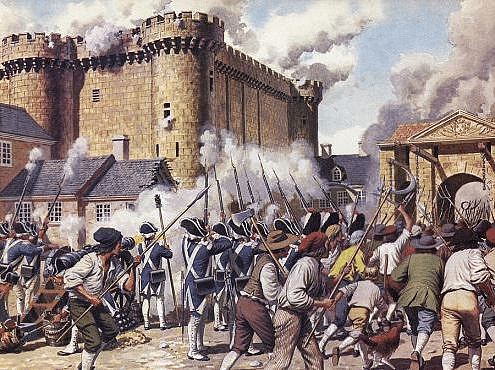

In the previous chapter, we saw how the French Revolution ignited ideas of freedom and equality, challenging old societal structures dominated by the aristocracy and the church. Before the eighteenth century, society was mainly divided into estates and orders, with the aristocracy and church holding considerable economic and social power. This upheaval had a global impact, inspiring thinkers like Raja Rammohan Roy in India and sparking discussions about societal change.

However, not everyone in Europe supported a complete overhaul. The political landscape included conservatives, who preferred minor adjustments; liberals, who advocated for gradual reforms; and radicals, who pushed for substantial change. The meanings of these terms varied depending on the context.

Change in Society after French Revolution

Change in Society after French Revolution

This chapter will delve into the key political traditions of the nineteenth century, focusing on the Russian Revolution, a crucial event that brought socialism to the forefront of global politics in the twentieth century.

Liberals, Radicals, and Conservatives

Liberals were a group of individuals seeking to change society. Their beliefs can be summarised as follows:

- Religious Tolerance: Most European countries supported specific religions (e.g., Britain favoured the Church of England, while Austria and Spain supported the Catholic Church). Liberals aimed to create a nation that accepted all religions, opposing discrimination based on religion and safeguarding individual rights against government actions.

- Limited Power of Dynastic Rulers: Liberals opposed the unchecked power of hereditary rulers. They argued for a representative, elected parliamentary government, governed by laws interpreted by an independent judiciary that was not influenced by rulers or officials.

- Selective Voting Rights: They believed that only property-owning men should have the vote and did not advocate for universal suffrage, meaning they did not support voting rights for all citizens, especially women.

In contrast, radicals aimed for a nation where the government reflected the majority of the population. Many supported women's suffrage movements. Unlike liberals, they opposed the privileges of wealthy landowners and factory owners. They did not object to private property but were against its concentration in the hands of a select few.

Conservatives opposed both radicals and liberals. After the French Revolution, even conservatives began to recognise the need for change. In the eighteenth century, they were largely resistant to change, but by the nineteenth century, they accepted that some change was unavoidable. They believed that the past should be respected and that change should occur gradually.

These differing views on societal change clashed during the social and political upheaval that followed the French Revolution. The various revolutionary attempts and national transformations of the nineteenth century contributed to defining the limits and potential of these political ideologies.

Socialism in Russian Revolution

Socialism in Russian Revolution

Radicals, Liberals, and Conservatives: Perspectives on Change

Radicals and liberals saw the need for change in society. In contrast, conservatives were against both radicals and liberals. In the eighteenth century, conservatives generally resisted change. However, after the French Revolution, even conservatives began to recognise the necessity of some change. They accepted that change was unavoidable but believed it should be gradual and that the past should be respected.

The different opinions on societal change often led to conflicts during the social and political turmoil that followed the French Revolution. The various revolutionary and nationalist movements of the nineteenth century tested the limits and potential of these political ideas, influencing their development and significance.

Industrial Society and Social Change

This period marked a significant shift, characterised by major social and economic transformations. New cities emerged, industrialised areas developed, and the Industrial Revolution took place.

- Industrialization Problems: As industrialisation began, many men, women, and children moved close to factories. However, this progress had serious downsides. Work hours were long, and wages were low. Unemployment was frequent, especially during slow periods for industrial goods. Rapid town growth led to urgent issues with housing and sanitation.

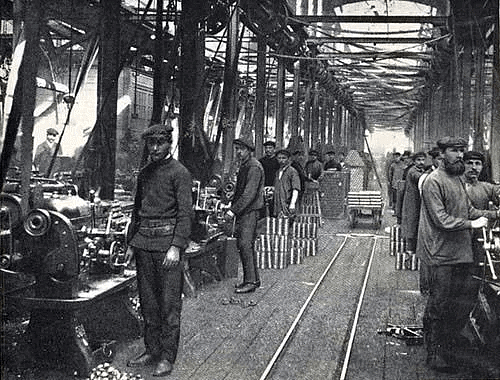

An image of Russian Industrial Workers in the 1890s

An image of Russian Industrial Workers in the 1890s

- Solution by Radicals and Liberals: In response to the challenges of industrialisation, liberals and radicals joined forces to find solutions. Both groups typically included property owners and employers who had gained wealth through their work and commerce. They believed that individual effort, hard work, and enterprise should be encouraged, as a healthy and educated workforce would benefit society. This belief led to increased involvement from the working class, who started to support liberals and radicals.

- Effects on the World: The ideas of radicals and liberals, along with conservative responses, significantly influenced the social and political landscape of the nineteenth century. The interactions and conflicts between these groups shaped the course of revolutions and national changes, ultimately defining the limits and opportunities of these political movements.

The Coming of Nationalism and Socialism in Europe

Many nationalists and liberals aimed to change the governments set up in Europe after 1815. In countries like France, Italy, Germany, and Russia, they became revolutionaries, seeking to overthrow the existing monarchs. Nationalists spoke of revolutions that would create 'nations' where all citizens enjoyed equal rights. After 1815, Giuseppe Mazzini, an Italian nationalist, worked with others to achieve this in Italy. Nationalists in other regions, including India, read his writings.

Louis Blanc

Louis Blanc

The Coming of Socialism to Europe

By the mid-nineteenth century, socialism had become a well-known set of ideas in Europe, gaining much attention. Socialists opposed private property, viewing it as the source of many social problems. Instead of allowing individuals to control property, they wanted a focus on collective social interests. Socialists had various visions for the future:

- Robert Owen (1771-1858), a prominent English manufacturer, aimed to establish a cooperative community named New Harmony in Indiana (USA).

- Louis Blanc (1813-1882) proposed that the government should support cooperatives and replace capitalist businesses. These cooperatives would be groups of people working together to produce goods and share profits based on individual contributions.

- Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) introduced additional ideas into this discussion. Marx argued that industrial society was fundamentally capitalist, where capitalists owned factories and profited from workers' labour. He believed that since profits were controlled by private capitalists, workers' conditions could not improve under capitalism.

- Marx asserted that workers needed to overthrow this system and eliminate private property. To escape exploitation by capitalists, workers should create a radically socialist society where all property was collectively managed. He was confident that workers would ultimately succeed in this struggle, leading to a future communist society. Through the revolution in Russia, socialism became one of the most influential ideas shaping society in the twentieth century.

Support for Socialism

By the 1870s, socialist ideas were spreading across Europe. An international organisation called the Second International was formed. Workers in England and Germany began establishing associations to campaign for better living and working conditions. They set up funds to assist members in times of need and demanded:

- A reduction in working hours

- The right to vote

In Germany, the Social Democratic Party gained parliamentary seats. By 1905, socialists and trade unionists had established a Labour Party in Britain and a Socialist Party in France. While their ideas influenced legislation, governments continued to be led by conservatives, liberals, and radicals.

The Russian Revolution

- The Russian Revolution was a time of major political and social change in the Russian Empire, starting with the end of the monarchy in 1917. This followed the February Revolution, which resulted in Tsar Nicholas II stepping down and a provisional government being formed. To understand the reasons behind this significant change, we should examine the situation in Russia just before the revolution.

The Russian Empire in 1914

- In 1914, Tsar Nicholas II was the ruler of Russia and its vast empire. Besides the area around Moscow, the empire included what are now Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, and parts of Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus. It extended to the Pacific Ocean and encompassed today’s Central Asian countries, along with Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The main religion was Russian Orthodox Christianity, which developed from the Greek Orthodox Church, but the empire also had followers of Catholicism, Protestantism, Islam, and Buddhism.

Political Context

- Russia was an autocracy. Unlike many other European leaders at the beginning of the 20th century, the Tsar was not accountable to a parliament. This lack of political representation played a significant role in the unrest that led to the revolution.

Economy and Society

- Agriculture Dominance: In the early 20th century, around 85% of the population worked in agriculture. Russia had a larger share of people reliant on farming compared to most European nations.

- Industrial Development: Industrialisation was primarily found in cities like St Petersburg and Moscow. Both craftsmen and large factories existed side by side, with significant factory growth in the 1890s. Russia became a leading exporter of grain. The expansion of the railway system and foreign investments during the 1890s boosted industrial growth, with coal production doubling and iron and steel output increasing fourfold.

- Working Conditions: Most industries were owned by private individuals. The government attempted to ensure minimum wages and limit working hours, but factory inspectors often faced challenges enforcing these rules. Many workers dealt with long hours, and living conditions varied greatly.

- Social Divisions Among Workers: The year 1904 was particularly harsh for workers in Russia, with prices for essential goods rising rapidly, leading to a 20% drop in real wages. Despite social divisions, workers often united to strike over disputes with employers regarding dismissals or working conditions.

- Peasant Conditions: Many unemployed peasants relied on charitable kitchens for food and lived in poor conditions. The dire living situations of peasants contributed to the social unrest that spurred the revolution.

- Impact of World War I: Initially, the war was popular in Russia, with people supporting Tsar Nicholas II. However, as the conflict dragged on, the Tsar's refusal to consult the main political parties in the Duma led to growing dissatisfaction among the general population.

Russian Empire in 1914

Russian Empire in 1914

Workers and Social Divisions

- Workers were socially divided based on their village ties, how long they had lived in cities, and their skill levels.

- These divisions showed in their clothing and behaviour.

- Women made up 31% of the factory workforce but earned less than men.

- Some workers formed associations to support each other during times of unemployment or financial struggles, but these were few in number.

- Despite these divisions, workers came together during strikes to protest against dismissals or poor working conditions.

- Frequent strikes occurred in the textile industry during 1896-1897 and in the metal industry in 1902.

Peasants and Land Ownership

- Peasants worked most of the land, but large estates were owned by the nobility, crown, and Orthodox Church.

- Peasants were very religious but had little respect for the nobility, unlike in France during the French Revolution.

- They wanted land redistribution and often refused to pay rent, leading to events like large-scale landlord murders in 1902 and widespread violence in 1905.

- Russian peasants were different from their European counterparts as they would pool their land periodically and divide it based on family needs in a communal system called “mir”.

Political Party Restrictions

- Before 1914, all political parties in Russia were banned, forcing groups like the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDWP) to operate illegally.

- The RSDWP was founded in 1898 and was inspired by Marxist ideas, organising strikes and mobilising workers through underground activities.

Views on Socialism

- Some socialists viewed Russian peasants, with their tradition of sharing land, as natural socialists who could lead the revolution.

- This belief led to the formation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1900, which advocated for peasant rights and land redistribution from nobles to peasants.

Differences Among Socialists

- The Socialist Revolutionary Party focused on issues affecting peasants, while Lenin and the Social Democrats believed peasants were divided.

- Lenin argued that differences among peasants, such as wealth and roles in labour, prevented them from being a unified revolutionary force.

Organisational Strategies

- Lenin’s Bolsheviks preferred a tightly controlled, disciplined party to withstand Tsarist repression.

- In contrast, the Mensheviks supported a more open membership model like that of the German socialist movement.

A Turbulent Time: The 1905 Revolution

Autocratic Rule

- Russia was an autocracy with the Tsar holding absolute power, without any parliamentary oversight.

- Groups such as liberals, Social Democrats, and Socialist Revolutionaries campaigned for an end to this system, asking for a constitution to limit the Tsar’s authority.

Support for Change

- Reform efforts gained backing from nationalists in Poland and Jadidists in Muslim regions, who wanted modernisation and relief from oppressive governance.

Economic Hardships and Worker Unrest

- An economic crisis in 1904 saw prices for essential goods soar, reducing real wages by 20%.

- This discontent led to protests, including a significant strike in St. Petersburg.

- In the Bloody Sunday incident, police and Cossacks attacked unarmed workers led by Father Gapon, resulting in over 100 deaths and around 300 injuries.

1905 Revolution

- The 1905 Revolution sparked widespread unrest, including strikes, student walkouts, and the formation of the Union of Unions, which called for a constituent assembly.

- The Tsar temporarily allowed the formation of a consultative Parliament (Duma) and permitted trade unions and factory committees to operate briefly.

Post-Revolution Repression

- After the revolution, the Tsar limited the Duma, dismissing the first two within months and altering voting laws to ensure a conservative majority in the third Duma.

- Political repression resumed, with the Tsar banning most political activities to silence liberals and revolutionaries.

The First World War and the Russian Empire

The Outbreak of World War I

- Central Powers: Germany, Austria, and Turkey

- Allied Powers: France, Britain, and Russia (later joined by Italy and Romania)

- Global Scope: The war was fought in Europe and overseas.

Initial Popularity and Declining Support

- At the start of the war, Tsar Nicholas II enjoyed widespread support in Russia.

- Over time, the Tsar’s refusal to consult the main parties in the Duma led to diminishing support.

- High anti-German sentiments resulted in renaming St. Petersburg (a German name) to Petrograd.

- The Tsarina Alexandra's German origins and poor advisers, especially a monk named Rasputin, made the autocracy unpopular.

Differences in War Fronts

- The Eastern Front saw moving armies and large battles with high casualties.

- Russia faced major defeats against Germany and Austria between 1914 and 1916.

- In contrast, trench warfare defined the Western Front.

Impact of the War on Russia

- By 1917, Russia had over 7 million casualties.

- The army's retreat caused destruction of crops and buildings, leading to over 3 million refugees.

- Severe conditions discredited the Tsar and the government.

- Russia’s limited industrial base and German control of the Baltic Sea disrupted supplies of industrial goods.

- Rapid deterioration of equipment and breakdowns in railway lines occurred by 1916.

- With most able-bodied men at war, labour shortages affected small workshops.

- Large grain supplies were sent to the army, resulting in shortages of bread and flour in cities.

- Riots over bread shortages became common by the winter of 1916.

The February Revolution in Petrograd

February Revolution

February Revolution

- The winter of 1917 was tough for the people of Petrograd. The city was divided, with workers living in the poorer areas on the right bank of the River Neva, while the left bank had the more affluent districts, the Winter Palace, and government buildings, including where the Duma met.

- Food shortages were a major issue, especially in the workers' areas. The winter was particularly cold and snowy. The effects of World War I had severely disrupted grain supplies, resulting in a lack of bread and flour. By winter 1916, riots over bread were common.

- Tensions rose as the government faced opposition from parliament members who wanted to maintain the elected government, while the Tsar aimed to dissolve the Duma.

- On 22 February, there was a lockout at a factory on the right bank. The next day, workers from fifty factories went on strike in support. Women were prominent in these protests; at the Lorenz telephone factory, Marfa Vasileva played a key role in organising a successful strike. In honour of International Women's Day, women workers gave red bows to their male colleagues, motivating them.

- After the initial protests, demonstrators regrouped on the 24th and 25th. On 25 February, the government suspended the Duma, leading to a resurgence of protests on the left bank of Petrograd the next day, with people demanding better conditions.

- On 27 February, the Police Headquarters was attacked, and the streets were filled with calls for bread, wages, better working hours, and democracy. Despite government attempts to suppress the protests, the cavalry refused to attack the demonstrators. This change in loyalty was crucial; when the Imperial Russian army began to support the revolutionaries, the Tsarist regime fell apart.

- Eventually, soldiers and striking workers united to form a council called the Petrograd Soviet in the same building where the Duma convened. Military leaders urged the Tsar to step down, which he did on 2 March.

- Leaders from the Soviet and the Duma created a Provisional Government to manage the country, effectively ending the monarchy in what is known as the February Revolution. The future of Russia would be determined by a constituent assembly elected based on universal adult suffrage.

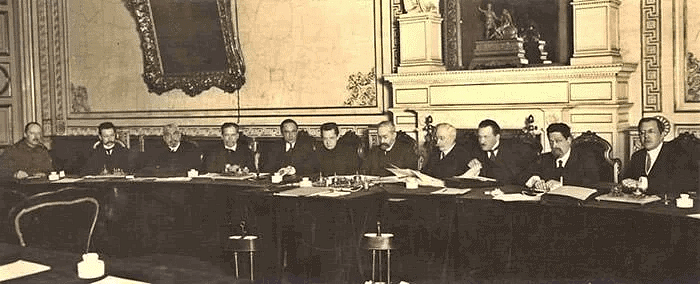

Russian Provisional Government in March 1917

Russian Provisional Government in March 1917

After February

- Army officials, landowners, and industrialists held significant power in the Provisional Government. However, both the liberals and socialists among them aimed for an elected government.

- Restrictions on public meetings and associations were lifted.

- In April 1917, Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks, returned to Russia from exile.

- He and the Bolsheviks had been against the war since 1914.

- Lenin announced his ‘April Theses’, which called for an end to the war, land to be given to the peasants, and the nationalisation of banks. These were Lenin's core demands.

- Initially, most in the Bolshevik Party were taken aback by the April Theses. They believed it was too early for a socialist revolution and that the Provisional Government should be supported. However, events in the following months shifted their views.

- The workers’ movement continued to grow throughout the summer, leading to the creation of factory committees and trade unions, as well as soldier committees within the army.

- In June, approximately 500 Soviets sent delegates to an All-Russian Congress of Soviets. There was no uniform system of election for these Soviets.

- As Bolshevik influence expanded and the Provisional Government weakened, the latter took harsh actions against the rising discontent, arresting leaders and resisting workers’ attempts to manage factories.

- In July 1917, the Bolsheviks organised popular demonstrations that were seemingly suppressed, forcing many of their leaders to go into hiding or flee.

The Revolution of October 1917

- Lenin grew increasingly worried that the Provisional Government might establish a dictatorship as tensions between them and the Bolsheviks heightened.

- In September, he began preparations for a rebellion against the government, rallying Bolshevik supporters from the army, Soviets, and factories.

- On 16 October 1917, Lenin convinced the Petrograd Soviet and the Bolshevik Party to endorse a socialist seizure of power. A Military Revolutionary Committee was appointed by the Soviet, led by Leon Trotskii, to plan the takeover. The date of the uprising was kept secret.

- The uprising commenced on 24 October. Anticipating unrest, Prime Minister Kerenskii left the city to call for troops. At dawn, military forces loyal to the government captured the offices of two Bolshevik newspapers.

- Government troops were dispatched to seize telephone and telegraph offices and to guard the Winter Palace.

- Later that day, the ship Aurora bombarded the Winter Palace, allowing the committee to capture the city and leading to the ministers' surrender.

- During a Petrograd meeting of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, the majority supported the Bolshevik actions.

- Uprisings also occurred in other cities, with intense fighting, particularly in Moscow.

- By December, the Bolsheviks had gained control over the Moscow-Petrograd region.

The Petrograd Soviet, the banner on the left reads, "Down with Lenin and Co."

The Petrograd Soviet, the banner on the left reads, "Down with Lenin and Co."

What Changed After October?

- Private property was strongly opposed by the Bolsheviks, who nationalised most industries and banks in November 1917. They also allowed peasants to take land from the nobility.

- They enforced the division of large homes in cities and prohibited the use of aristocratic titles.

- The army and officials received new uniforms to signify the change.

- The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik). In November 1917, they held elections for the Constituent Assembly but did not secure majority support.

- The Assembly rejected Bolshevik proposals, resulting in its dismissal by Lenin in January 1918.

- Despite opposition from political allies, the Bolsheviks signed a peace treaty with Germany at Brest Litovsk in March 1918.

- In the following years, the Bolsheviks became the only party to participate in elections for the All Russian Congress of Soviets, which evolved into the country's Parliament, establishing Russia as a one-party state.

The Civil War (1917 – 20)

- After the Bolsheviks ordered land redistribution, the Russian army broke apart, with soldiers—mostly peasants—deserting to go home for land.

- Opponents of the Bolsheviks, including non-Bolshevik socialists, liberals, and supporters of autocracy, condemned the Bolshevik uprising. Their leaders moved to southern Russia to organise troops to fight the Reds. They received support from French, American, British, and Japanese troops, who were concerned about the rise of socialism in Russia.

- During 1918 and 1919, the Socialist Revolutionaries (known as "greens") and pro-Tsarists (referred to as "whites") controlled most of the Russian empire. As these troops fought the Bolsheviks in a civil war, looting, banditry, and famine became widespread.

- Supporters of private property among the "whites" took severe actions against peasants who had seized land, leading to a loss of popular support for the non-Bolsheviks.

- By January 1920, the Bolsheviks had taken control of most of the former Russian empire. To gain support, they granted political autonomy to non-Russian nationalities in the Soviet Union (USSR), established by the Bolsheviks from the Russian empire in December 1922. However, their attempts to win over different nationalities were only partially successful, as they enforced unpopular policies on local governments, such as the harsh discouragement of nomadism.

Making a Socialist Society

1. Economic Policies

- Nationalization: During the civil war, the Bolsheviks kept industries and banks nationalised.

- Land Cultivation: Peasants were allowed to cultivate land that had been socialized.

- Centralized Planning: A system of centralised planning was introduced. Officials evaluated how the economy could operate and set goals for a five-year period, resulting in the creation of the Five Year Plans.

- First Two Five-Year Plans (1927-1932 and 1933-1938): These plans focused on industrial growth, with fixed prices across various sectors.

- Economic Growth: Industrial production experienced substantial increases, including a 100% rise in oil, coal, and steel production from 1929 to 1933.

2. Industrialization and Its Challenges

- Rapid Construction: New industrial cities, such as Magnitogorsk, were built rapidly. The steel plant in Magnitogorsk was finished in just three years.

- Working Conditions: Working conditions were tough, with frequent work stoppages and challenging living situations. Workers often encountered many difficulties.

3. Social Policies

- Extended Schooling: Education was broadened, giving factory workers and peasants a chance to attend universities.

- Crèches: Childcare facilities were set up in factories to assist working women.

- Public Health Care: Affordable public health care services were made available.

- Model Living Quarters: Some model living quarters were created for workers, although their availability was limited due to tight government resources.

4. Stalinism and Collectivization

- Context of Early Planned Economy: In the late 1920s, Soviet towns faced serious grain shortages as government price controls led peasants to withhold their grain, showing the flaws in early Soviet economic policies.

- Stalin’s Emergency Measures: After Lenin’s death, Stalin took over and blamed wealthy peasants, or "kulaks", for hoarding grain. He enforced strict grain collections, with party members raiding kulaks to obtain food supplies.

- The Collectivization Program: It was argued that grain shortages were partly due to the small size of holdings. Stalin launched collectivization in 1929, forcing peasants into state-controlled farms (kolkhozes) to modernise agriculture. Peasants shared land, tools, and profits under state supervision.

- Resistance and Consequences: Many peasants resisted collectivization by destroying their livestock, leading to a significant drop in cattle numbers. Resistance was met with harsh punishment, and independent farming was pushed to the margins.

- Impact, Criticism, and Repression: Collectivization resulted in a devastating famine (1930-1933), causing millions of deaths. Criticism within the party arose, but Stalin responded with severe repression, imprisoning or executing over 2 million people by 1939.

The Global Influence of the Russian Revolution and the USSR

1. International Response to Bolshevism

- The rise of the Bolsheviks led to mixed reactions worldwide.

- European socialists were cautious about the authoritarian methods, yet the idea of a workers' state motivated communist parties globally, including the Communist Party of Great Britain.

- The Bolsheviks encouraged colonial peoples to emulate their model, promoting it internationally.

- Many non-Russians participated in the Conference of the Peoples of the East (1920) and the Bolshevik-founded Comintern, boosting the USSR's global influence by World War II.

2. Internal Criticism and Decline

- By the 1950s, there was recognition within the USSR that its government style did not align with the ideals of the Russian Revolution.

- International socialists raised concerns about the restrictions on freedoms and the USSR’s development approach.

- A previously backward country had transformed into a great power with developed industries and agriculture, feeding the poor.

- However, the government denied essential freedoms to its citizens and enforced its development through repressive policies.

3. Development vs. Freedom

- While the USSR achieved significant economic progress, its suppression of freedoms attracted criticism.

- Socialists argued that true socialist values were being compromised, leading to discussions about the balance between growth and individual rights.

4. Decline in Reputation

- By the end of the twentieth century, the international standing of the USSR as a socialist nation had diminished.

- Despite this, socialist ideals continued to hold respect among its populace.

- Many outside the USSR questioned its commitment to genuine socialism.

5. Reevaluation of Socialism

- The Soviet model prompted a global reevaluation of socialism.

- Various nations began to adopt socialist ideas that emphasised freedom and rights, leading to new, localised forms of socialism.

Difficult Words

- Suffragette movement: A movement to give women the right to vote.

- Jadidists: Muslim reformers within the Russian Empire.

- Real wage: Reflects the amounts of goods that wages can buy.

- Autonomy: The right to govern themselves.

- Nomadism: A lifestyle of people who move from place to place to earn a living.

- Deported: Forcibly removed from one’s own country.

- Exiled: Forced to live away from one’s own country.

- Aristocracy: A class of people with special rank and privileges, especially the hereditary nobility.

- Dynastic: Related to a dynasty, a sequence of rulers from the same family.

- Franchise: The right to vote in public elections.

- Judiciary: The judges of a country; judicial authorities collectively.

- Cooperatives: Enterprises owned by and operated for the benefit of those using their services.

- Autocracy: A government system where one person has absolute power.

- Provisional: Existing for the present, possibly to change later.

- Soviet: A governing council in the former Soviet Union, usually elected from workplaces or army units.

- Constituent: A part of a whole; a component.

- Kulaks: Wealthy peasants in the Soviet Union who owned larger farms and used hired labour; they were targeted during Stalin's forced collectivisation.

- Collective farms (kolkhoz): Agricultural cooperatives in the Soviet Union where land and equipment were pooled for collective farming.

- Planned Economy: An economic system where the government controls and regulates production, distribution, and prices.

Some important dates

- 1850s - 1880s: Debates over socialism in Russia.

- 1898: Formation of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party.

- 1905: Bloody Sunday and the Revolution of 1905.

- 1917: 2nd March - Abdication of the Tsar; 24th October - Bolshevik uprising in Petrograd.

- 1918-20: The Civil War.

- 1919: Formation of Comintern.

- 1929: Beginning of Collectivisation.

Note on Calendar Change: Russia followed the Julian calendar until 1 February 1918. It then changed to the Gregorian calendar, which is used everywhere today. The Gregorian dates are 13 days ahead of the Julian dates. Thus, according to our calendar, the 'February' Revolution took place on 12th March and the 'October' Revolution on 7th November.

Context on Conditions in 1904: The year 1904 was particularly difficult for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose quickly, leading to a 20% decline in real wages.

|

53 videos|437 docs|80 tests

|

FAQs on Class 9 History Chapter 2 Notes - Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution

| 1. What were the main causes of the February Revolution in Petrograd? |  |

| 2. How did the October Revolution differ from the February Revolution? |  |

| 3. What were the global influences of the Russian Revolution? |  |

| 4. What changes occurred in Russia after the October Revolution? |  |

| 5. How did the Russian Revolution contribute to the rise of socialism in Europe? |  |

|

Explore Courses for Class 9 exam

|

|