Normal Shocks - 2 | Fluid Mechanics for Mechanical Engineering PDF Download

Rayleigh Line Flows

Consider the effects of heat transfer on a frictionless compressible flow through a duct, the governing Eq. (41.1), (41.2a), (41.5), (38.8) and (41.6) are valid between any two points "1" and "2".

Equation (41.3) requires to be modified in order to account for the heat transferred to the flowing fluid per unit mass, dQ , and we obtain

(41.8)

(41.8)

So, for frictionless flow of an ideal gas in a constant area duct with heat transfer, we have a situation of six equations and seven unknowns. If all conditions at state "1" are known, there exists infinite number of possible states "2". With an infinite number of possible states "2" for a given state "1", we find if all possible states "2" are plotted on a T- s diagram, The locus of all possible states "2" reachable from state "1" is a continuous curve passing through state "1".

Again, the question arises as to how to determine this curve? The simplest way is to assume different values of T2 . For an assumed value of T2, the corresponding values of all other properties at "2" and dQ can be determined. The results of these calculations are shown in the figure below. The curve in Fig. 41.4 is called the Rayleigh line.

- At the point of maximum temperature (point "c" in Fig. 41.4) , the value of Mach number for an ideal gas is

At the point of maximum entropy( point "b") , the Mach number is unity.

At the point of maximum entropy( point "b") , the Mach number is unity. On the upper branch of the curve, the flow is always subsonic and it increases monotonically as we proceed to the right along the curve. At every point on the lower branch of the curve, the flow is supersonic, and it decreases monotonically as we move to the right along the curve.

Irrespective of the initial Mach number, with heat addition, the flow state proceeds to the right and with heat rejection, the flow state proceeds to the left along the Rayleigh line. For example , Consider a flow which is at an initial state given by 1 on the Rayleigh line in fig. 41.4. If heat is added to the flow, the conditions in the downstream region 2 will move close to point "b". The velocity reduces due to increase in pressure and density, and Ma approaches unity. If dQ is increased to a sufficiently high value, then point "b" will be reached and flow in region 2 will be sonic. The flow is again choked, and any further increase in dQ is not possible without an adjustment of the initial condition. The flow cannot become subsonic by any further increase in dQ .

The Physical Picture of the Flow through a Normal Shock

It is possible to obtain physical picture of the flow through a normal shock by employing some of the ideas of Fanno line and Rayleigh line Flows. Flow through a normal shock must satisfy Eqs (41.1), (41.2a), (41.3), (41.5), (38.8) and (41.6).

Since all the condition of state "1" are known, there is no difficulty in locating state "1" on T-s diagram. In order to draw a Fanno line curve through state "1", we require a locus of mathematical states that satisfy Eqs (41.1), (41.3), (41.5), (38.8) and (41.6). The Fanno line curve does not satisfy Eq. (41.2a).

While Rayleigh line curve through state "1" gives a locus of mathematical states that satisfy Eqs (41.1), (41.2a), (41.5), (38.8) and (41.6). The Rayleigh line does not satisfy Eq. (41.3). Both the curves on a same T-s diagram are shown in Fig. 41.5.

We know normal shock should satisfy all the six equations stated above. At the same time, for a given state" 1", the end state "2" of the normal shock must lie on both the Fanno line and Rayleigh line passing through state "1." Hence, the intersection of the two lines at state "2" represents the conditions downstream from the shock.

In Fig. 41.5, the flow through the shock is indicated as transition from state "1" to state "2". This is also consistent with directional principle indicated by the second law of thermodynamics, i.e. s2>s1.

From Fig. 41.5, it is also evident that the flow through a normal shock signifies a change of speed from supersonic to subsonic. Normal shock is possible only in a flow which is initially supersonic.

Fig 41.5 Intersection of Fanno line and Rayleigh line and the solution for normal shock condition

Calculation of Flow Properties Across a Normal Shock

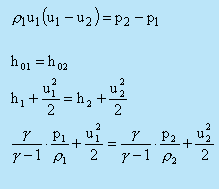

The easiest way to analyze a normal shock is to consider a control surface around the wave as shown in Fig. 41.2. The continuity equation (41.1), the momentum equation (41.2) and the energy equation (41.3) have already been discussed earlier. The energy equation can be simplified for an ideal gas as

T01 =T02 (40.9)

- By making use of the equation for the speed of sound eq. (39.5) and the equation of state for ideal gas eq. (38.8), the continuity equation can be rewritten to include the influence of Mach number as:

(40.10)

(40.10)

Introducing the Mach number in momentum equation, we have

Therefore ,

(40.11)

(40.11)

Rearranging this equation for the static pressure ratio across the shock wave, we get

(40.9)

(40.9)

As already seen, the Mach number of a normal shock wave is always greater than unity in the upstream and less than unity in the downstream, the static pressure always increases across the shock wave.

The energy equation can be written in terms of the temperature and Mach number using the stagnation temperature relationship (40.9) as

(40.13)

(40.13)

Substituting Eqs (40.12) and (40.13) into Eq. (40.10) yields the following relationship for the Mach numbers upstream and downstream of a normal shock wave:

(40.14)

(40.14)

Then, solving this equation for Ma2 as a function of Ma1 we obtain two solutions. One solution is trivial Ma2 = Ma1 , which signifies no shock across the control volume. The other solution is

(40.15)

(40.15)

Ma1 = 1 in Eq. (40.15) results in Ma2 = 1

Equations (40.12) and (40.13) also show that there would be no pressure or temperature increase across the shock. In fact, the shock wave corresponding to Ma1 = 1 is the sound wave across which, by definition, pressure and temperature changes are infinitesimal. Therefore, it can be said that the sound wave represents a degenerated normal shock wave. The pressure, temperature and Mach number (Ma2) behind a normal shock as a function of the Mach number Ma1, in front of the shock for the perfect gas can be represented in a tabular form (known as Normal Shock Table). The interested readers may refer to Spurk[1] and Muralidhar and Biswas[2]

Oblique Shock

The discontinuities in supersonic flows do not always exist as normal to the flow direction. There are oblique shocks which are inclined with respect to the flow direction. Refer to the shock structure on an obstacle, as depicted qualitatively in Fig.41.6.

The segment of the shock immediately in front of the body behaves like a normal shock.

- Oblique shock can be observed in following cases-

- Oblique shock formed as a consequence of the bending of the shock in the free-stream direction (shown in Fig.41.6)

- In a supersonic flow through a duct, viscous effects cause the shock to be oblique near the walls, the shock being normal only in the core region.

- The shock is also oblique when a supersonic flow is made to change direction near a sharp corner

The relationships derived earlier for the normal shock are valid for the velocity components normal to the oblique shock. The oblique shock continues to bend in the downstream direction until the Mach number of the velocity component normal to the wave is unity. At that instant, the oblique shock degenerates into a so called Mach wave across which changes in flow properties are infinitesimal.

Let us now consider a two-dimensional oblique shock as shown in Fig.41.7 below

For analyzing flow through such a shock, it may be considered as a normal shock on which a velocity  (parallel to the shock) is superimposed. The change across shock front is determined in the same way as for the normal shock. The equations for mass, momentum and energy conservation , respectively, are

(parallel to the shock) is superimposed. The change across shock front is determined in the same way as for the normal shock. The equations for mass, momentum and energy conservation , respectively, are

(41.16)

(41.16)

(41.18)

(41.18)

These equations are analogous to corresponding equations for normal shock. In addition to these, we have

Modifying normal shock relations by writing Ma1 sin α and Ma2 sin β in place of Ma1 and Ma2 , we obtain

(41.19)

(41.19)

(41.20-)

(41.20-)

(41.21)

(41.21)

Note that although Ma2 sin β < 1, Ma1 might be greater than 1. So the flow behind an oblique shock may be supersonic although the normal component of velocity is subsonic.

In order to obtain the angle of deflection of flow passing through an oblique shock, we use the relation

Having substituted  from Eq. (41.20), we get the relation

from Eq. (41.20), we get the relation

(41.22)

(41.22)

Sometimes, a design is done in such a way that an oblique shock is allowed instead of a normal shock. The losses for the case of oblique shock are much less than those of normal shock.This is the reason for making the nose angle of the fuselage of a supersonic aircraft smal

|

56 videos|104 docs|75 tests

|

FAQs on Normal Shocks - 2 - Fluid Mechanics for Mechanical Engineering

| 1. What are normal shocks in mechanical engineering? |  |

| 2. How do normal shocks form in mechanical engineering? |  |

| 3. What are the effects of normal shocks on mechanical systems? |  |

| 4. How can normal shocks be mitigated or controlled in mechanical engineering? |  |

| 5. What are some practical applications of normal shocks in mechanical engineering? |  |

|

56 videos|104 docs|75 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for Mechanical Engineering exam

|

|