Colligative Properties of a Solution | Physical Chemistry PDF Download

11. Colligative Properties

In chemistry, colligative properties are properties of solutions that depend on the ratio of the number of solute particles to the number of solvent molecules in a solution, and not on the nature of the chemical species present. The number ratio can be related to the various unit s for concentration of solutions. The assumption that solution properties are independent of nature of solute particles is only exact for ideal solutions, and is approximate for dilute real solutions. In other words, colligative properties are a set of solution properties that can be reasonably approximated by assuming that the solution is ideal.

Here we consider only properties which result from the dissolution of nonvolatile solute in a volatile liquid solvent. They are essentially solvent properties which are changed by the presence of the solute. The solute particles displace some solvent molecules in the liquid phase and therefore reduce the concentration of solvent, so that the colligative properties are independent of the nature of the solute. The word colligative is derived from the Latin colligatus meaning bound together.

Colligative properties include:

· Relative lowering of vapor pressure

· Elevation of boiling point

· Depression of freezing point

· Osmotic pressure

For a given solute-solvent mass ratio, all colligative properties are inversely proportional to solute molar mass.

Measurement of colligative properties for a dilute solution of a non-io nized solute such as urea or glucose in water or another solvent can lead to determinations of relative molar masses, both for small molecules and for polymers which cannot be studied by other means. Alternatively, measurements for ionized solutes can lead to an estimation of the percentage of dissociation taking place.

Colligative properties are mostly studied for dilute solutions, whose behavior may often be approximated as that of an ideal solution.

12. Lowering of Vapour Pressure by a Non-volatile Solute

It has been known for a long time that when a non-volatile solute is dissolved in a liquid, the vapour pressure of the solution becomes lower than the vapour pressure of the pure solvent. In 1886, the French chemist, Francois Raoult, after a series of experiments on a number of solvent including water, benzene and either, succeeded in establishing a relationship between the lowering of vapour pressure of a solution and the mole fraction of the non-volatile solute.

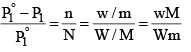

Let us consider a solution obtained by dissolving n moles of a non-volatile solute in N moles of a volatile solvent. Then mo le fract ion of the so lvent, X1 = N/(n + N) and mole fraction of the solute, X2 = n (N + n). Since the solute is non-volatile, it would have negligible vapour pressure.

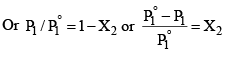

The vapour pressure of the solution is, therefore merely the vapour pressure of the solvent According to Raoult’s law, the vapour pressure of a solvent (P1) in an ideal solution is given by the expression;

P1 = X1P°1 …………………(1)

Where P°1 is the vapour pressure of the pure solvent. Since X1 + X2 = 1, Equation 1 may be written as

P1 = (1 – X2) P°1 …………………(2)

.................(3)

.................(3)

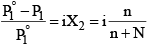

The expression on the left hand side of equation (3) is usually called the relative lowering of vapour pressure. Equation (3) may thus be stated as: The relative lowering of vapour pressure of a solution containing a non-volatile solute is equal to the mole fraction of the solute present in the solution.

This is one of the statements of the Raoult’s law.

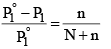

Since mole fraction of the solute, X2 is given by n(N + n), Equation (3) may be expressed as

.....................(4)

.....................(4)

It is evident from equation (4) that the lowering of vapour pressure of a solution depends upon the number of moles (and hence on the number of molecules) of the solute and not upon the nature of the solute dissolved in a given amount of the solvent. Hence, lowering of vapour pressure is a Colligative property.

Determination of Molar Masses from Lowering of Vapour Pressure

It is possible to calculate molar masses of non-volatile non-electrolytic solute by measuring vapour pressure of their solutions.

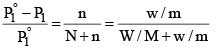

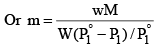

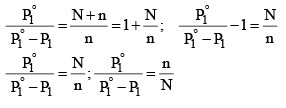

Suppose, a given mass, w gram, a solute of molar mass m, dissolved in W gram of solvent of molar mass M, lowers the vapour pressure fro m P°1 to P1.

Then, by equation (4)

...............(5)

...............(5)

Since in dilute solute, n is very small as compared to N, equation (5) may be put in the approximate form as

...............(6)

...............(6)

Alternatively, we can derive the relation without taking any approximations.

Limitations of Raoult’s Law

(i) Raoult’s law is applicable only to very dilute solutions.

(ii) It is applicable to solutions containing non-volatile solute only.

(iii) It is not applicable to solutes which dissociate or associate in a particular solution.

Example: The density of a 0.438 M solution of potassium chromate at 298 K is 1.063 g cm–3. Calculate the vapour pressure of water above this solution.

Given: P° (water) = 23.79 mm Hg.

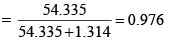

Solution: A solution of 0.438 M means 0.438 mol of K2CrO4 is present in 1 L of the solution. Now, Mass of K2CrO4 dissolved per litre of the solution = 0.438 × 194 = 84.972 g Mass of 1 L of solution = 1000 × 1.063 = 1063 g

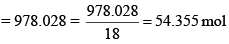

Amount of water in 1 L of solution

Assuming K2CrO4 to be completely dissociated in the solution, we will have; Amount of total solute species in the solution = 3 × 0.438

= 1.314 mol.

Mole fraction of water solution

Finally, vapour pressure of water above solution = 0.976 × 23.79 = 23.22 mm Hg.

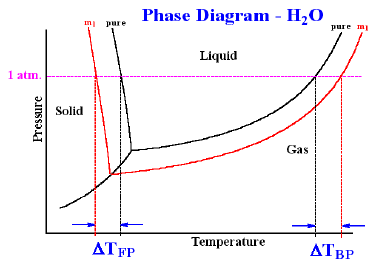

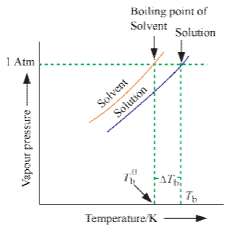

13. Boiling Point Elevation by a Non-Volatile Solute

The boiling point of a liquid is the temperature at which its vapour pressure becomes equal to 760 mm (i.e. 1 atmospheric pressure). Since the addition of a non-volatile solute lowers the vapour pressure of the solvent, the vapour pressure of a solution is always lower than that of the pure solvent, and hence it must be heated to a higher temperature to make its vapour pressure equal to atmospheric pressure. Thus the solution boils at a higher temperature than the pure solvent. If T°b is the boiling point of the solvent and Tb is the boiling of the solution, the difference in boiling point (ΔTb) is called the elevation of boiling point.

Thus, Tb – T°b = ΔTb.

T°b ∝ molalit y where ΔTb = elevation of boiling point.

This implies that the boiling point elevation in a dilute solution is directly proportional to the number of moles of the solute dissolved in a given amount of the solvent and is quite independent of the nature of the solute. Hence, boiling point elevation is a Colligative property.

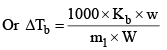

ΔTb = Kb × m, Kb: molal elevat ion constant to Ebullioscopic constant

M: molality of the solution

Molal boiling point elevation constant or ebullioscopic constant of the solvent, is defined as the elevation in boiling point which may theoretically be produced by dissolving one mole of any solute in 1000 g of the solvent.

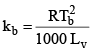

Where m1 = molecular weight of solute and w and W are weight of solute and solvent respectively in gram. Molal elevation constant is characteristic of particular solvent and can be calculated from the following thermodynamical relationship.

Where R = gas constant,

Tb = Boiling po int in K scale

Lv = latent heat of evaporation in cal/gm

14. Depression of Freezing Point by a Non-Volatile Solute

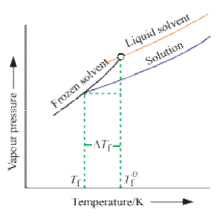

Freezing point is the temperature at which solid and liquid states of a substance have the same vapour pressure. It is observed that the freezing point of the solution (Tf) containing non volatile solute is always less than the freezing po int of the pure solvent (T°f). Thus Tf° - Tf = ΔTf .

It can be seen that ΔTf ∝ molality

That, is freezing po int depression of a dilute solution is directly proportional to the number of moles of the solute dissolved in a given amount of the solvent and is independent of the nature of solute.

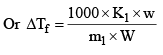

Or ΔTf = Kf m

Kf: molal freezing point depression constant of the solvent or cryoscopic constant

M: Molality of the solution

Molal freezing point depression constant of the solvent or cryoscopic constant, is defined as the depression in freezing point which may theoretically by produced by dissolving 1 mole of any solute in 1000 g of the solvent.

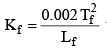

Where m1 = molecular weight of solute and w and W are weights of so lute and solvent. Kf is characterist ic of a solvent and can be calculated as follows.

where Lf = Latent heat of fusion and Tf = Freezing temperature in K scale.

where Lf = Latent heat of fusion and Tf = Freezing temperature in K scale.

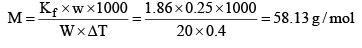

Example: An aqueous solution containing 0.25 g of a solute dissolved in 20 g of water freezes at 0.4°C. Calculate the mo lar mass of the solute. Kf = 1.86 K kg mol–1

Solution: ΔTf = Kf × m

15. Osmosis and Osmotic Pressure

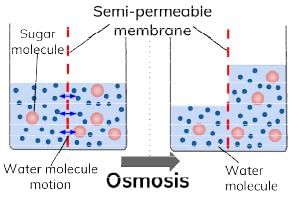

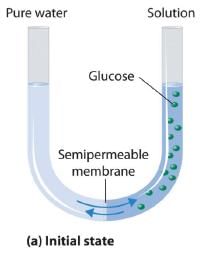

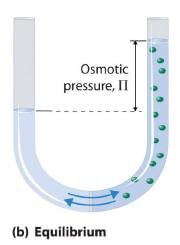

The phenomenon of the passage of pure solvent from a region of lower concentration (of the solution) to a region of its higher concentration through a semi-permeable membrane is called osmosis.

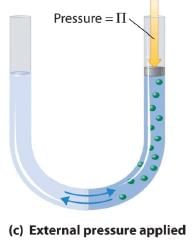

The driving force of osmosis is what is known as osmotic pressure. It is the difference in the pressure between the solution and the solvent system or it is the excess pressure which must be applied to a solution in order to prevent flow of solvent into the solution through the semi-permeable membrane. Once osmosis is complete the pressure exerted by the solution and the solvent on the semi-permeable membrane is same.

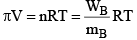

Van’t Hoff equation for dilute solution is (parallel to ideal gas equation)

πV = nRT

Where π = Osmot ic pressure, V = volume of solution, n = no. of moles of solute that is dissolved R = Gas constant, T = Absolute temperature

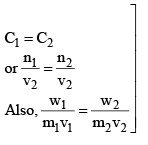

Isotonic Solutions

A pair of solutions having same osmotic pressure are called isotonic solutions.

For isotonic solution, π1 = π2 (Primary condition)

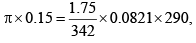

Example: Calculate the osmotic pressure of sucrose solution containing 1.75 gms in 150 ml of solution at 17°C.

Solution: We know that

π = 0.812 atm.

π = 0.812 atm.

16. Abnormal Molecular Weight and Van’t Hoff Factor

Since Colligative properties depend upon the number of particles of the solute, in some cases where the solute associates in solution, abnormal results for molecular masses are obtained.

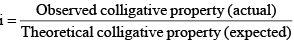

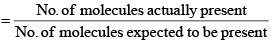

(i) Van’t Hoff factor: Van’t Hoff, in order to account for all abnormal cases introduced a factor i know as the van’t Hoff factor, such that

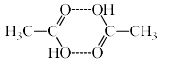

(ii) Association: There are many organic solutes which in non-aqueous solutions undergo association, that is two or more molecules of the solute associate to form a bigger molecule. Thus, the number of effective molecules decreases and consequently the osmotic pressure, the elevation of boiling point or depression of freezing point, is less than that calculate on the basis of a single molecule. Two example are: acetic acid in benzene and chloroacetic acid in naphthalene.

Association of Acitic acid in benzene through hydrogen bonding.

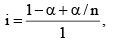

(iii) Degree of Association: It is the fraction of the total number of molecules which combine to form bigger molecule. Consider one mole of solute dissolved in a given volume of solvent. Suppose n simple molecule combine to form an associated molecule.

i.e., nA ⇋ (A)n

Let α be the degree of association, then

The number of unassociated moles = 1 – a

The number of associated moles = α/n

Total number of effect ive moles = 1 - α + α/n

Obviously, I < 1

(iv) Dissociation: Organic acids, and salts in aqueous solutions undergo dissociation, that is, the molecules break down into positively and negatively charged ions. In such cases, the number of effective particles increases and, therefore, osmotic pressure, elevation of boiling point and depression of freezing point are much higher than those calculated on the basis of an undissociated single molecule.

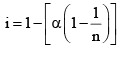

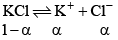

(v) Degree of dissociation: Degree of dissociation means the fraction of the total number of molecules which dissociates in the solution, that is, breaks into simpler molecular or ions. Consider one mole of an univalent electrolyte like potassium chloride disso lved in a given volume of water. Let α be its degree of dissociation.

Then the number of moles of KCl left undissociated will be 1 – α. At the same time, α moles of K+ ions and α moles of Cl- ions will be produced, as shown below.

Thus, the total number of moles of after dissociat ion = 1 – α + α + α = 1 – α.

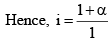

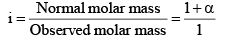

Since, as already, mentioned, osmotic pressure, vapour pressure lowering, boiling point elevation or freezing point depressions way very inversely as the molecules weight of the solute, if follows that,

i = 1 + α = 1 + (2 – 1) α

In general, i = 1 + (n – 1) α, where n = number of particles (ions) formed after dissociation fro m the above formula, it is clear that i > 1

Knowing, the observed mo lar mass and the Van’t Hoff factor, i, the degree of dissociat ion, a can be easily calculated.

Now, if we include Van’t Hoff factor in the formulae for Colligative properties, we obtain the normal results:

1. Relative lowering of vapour pressure,

2. Osmotic pressure, π = iCRT

3. Elevation of boiling point, Δ Tb = i1000 × Kb × molality

4. Depression in freezing point, Δ Tf = i1000 × Kf × molality

Note: The value of i is taken as one when solute is non electrolyte.

|

83 videos|142 docs|67 tests

|

FAQs on Colligative Properties of a Solution - Physical Chemistry

| 1. What are colligative properties of a solution? |  |

| 2. How does adding solute affect the boiling point of a solution? |  |

| 3. What causes freezing point depression in a solution? |  |

| 4. How is osmotic pressure related to colligative properties? |  |

| 5. How does the presence of solute affect the vapor pressure of a solution? |  |

|

Explore Courses for Chemistry exam

|

|