Real Roots, First Order Differential Equations | Calculus - Mathematics PDF Download

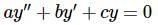

It’s time to start solving constant coefficient, homogeneous, linear, second order differential equations. So, let’s recap how we do this from the last section. We start with the differential equation.

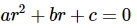

Write down the characteristic equation.

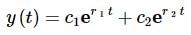

Solve the characteristic equation for the two roots, r1 and r2. This gives the two solutions

Now, if the two roots are real and distinct (i.e. r1≠r2) it will turn out that these two solutions are “nice enough” to form the general solution

As with the last section, we’ll ask that you believe us when we say that these are “nice enough”. You will be able to prove this easily enough once we reach a later section.

With real, distinct roots there really isn’t a whole lot to do other than work a couple of examples so let’s do that.

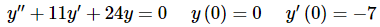

Example 1: Solve the following IVP.

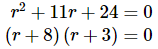

Solution: The characteristic equation is

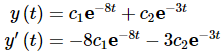

Its roots are r1=−8 and r2=−3 and so the general solution and its derivative is.

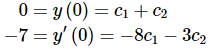

Now, plug in the initial conditions to get the following system of equations.

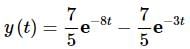

Solving this system gives c1=7/5 and c2=−7/5. The actual solution to the differential equation is then

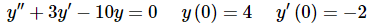

Example 2: Solve the following IVP

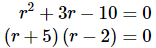

Solution: The characteristic equation is

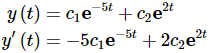

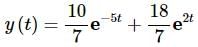

Its roots are r1=−5 and r2=2 and so the general solution and its derivative is.

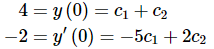

Now, plug in the initial conditions to get the following system of equations.

Solving this system gives c1=10/7 and c2=18/7. The actual solution to the differential equation is then

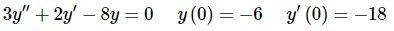

Example 3: Solve the following IVP.

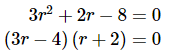

Solution: The characteristic equation is

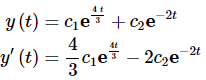

Its roots are r1=4/3 and r2=−2 and so the general solution and its derivative is.

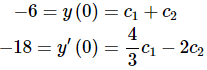

Now, plug in the initial conditions to get the following system of equations.

Solving this system gives

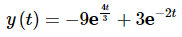

c1=−9 and c2=3. The actual solution to the differential equation is then.

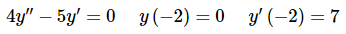

Example 4: Solve the following IVP

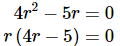

Solution: The characteristic equation is

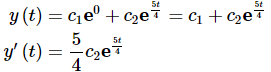

The roots of this equation are r1=0 and r2=5/4. Here is the general solution as well as its derivative.

Up to this point all of the initial conditions have been at t=0 and this one isn’t. Don’t get too locked into initial conditions always being at t=0 and you just automatically use that instead of the actual value for a given problem.

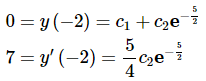

So, plugging in the initial conditions gives the following system of equations to solve.

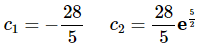

Solving this gives.

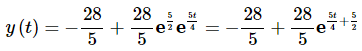

The solution to the differential equation is then.

In a differential equations class most instructors (including me….) tend to use initial conditions at t=0 because it makes the work a little easier for the students as they are trying to learn the subject. However, there is no reason to always expect that this will be the case, so do not start to always expect initial conditions at t=0!

Let’s do one final example to make another point that you need to be made aware of.

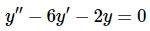

Example 5: Find the general solution to the following differential equation.

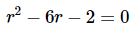

Solution: The characteristic equation is.

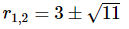

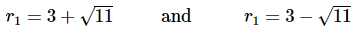

The roots of this equation are.

Now, do NOT get excited about these roots they are just two real numbers.

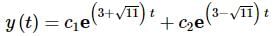

Admittedly they are not as nice looking as we may be used to, but they are just real numbers. Therefore, the general solution is

If we had initial conditions we could proceed as we did in the previous two examples although the work would be somewhat messy and so we aren’t going to do that for this example.

The point of the last example is make sure that you don’t get to used to “nice”, simple roots. In practice roots of the characteristic equation will generally not be nice, simple integers or fractions so don’t get too used to them!

|

112 videos|65 docs|3 tests

|

FAQs on Real Roots, First Order Differential Equations - Calculus - Mathematics

| 1. What are real roots in the context of first-order differential equations? |  |

| 2. How can we determine if a first-order differential equation has real roots? |  |

| 3. Can a first-order differential equation have multiple real roots? |  |

| 4. Are all real roots of a first-order differential equation meaningful in the context of the problem being solved? |  |

| 5. How can we interpret the real roots of a first-order differential equation in the context of a real-world problem? |  |