Reading for IELTS Academic Practice Test- 23 | Reading Practice Tests for IELTS Academic PDF Download

Section - 1

(A) Our ancestor. Homo erectus, may not have had culture or even language, but did they have teenagers? That question has been contested in the past few years, with some anthropologists claiming evidence of an adolescent phase in human fossil. This is not merely an academic debate. Humans today are the only animals on Earth to have a teenage phase, yet we have very little idea why. Establishing exactly when adolescence first evolved and finding out what sorts of changes in our bodies and lifestyles it was associated with could help US understand its purpose. Why do we, uniquely' have a growth spurt so late in life?

(B) Until recently, the dominant explanation was that physical growth is delayed by our need to grow large brains and to learn all the behavior patterns associated with humanity - speaking, social interaction and so on. While such behaviour is still developing, humans cannot easily fend for themselves, so it is best to stay small and look youthful. That way your parents and other members of the social group are motivated to continue looking after you. What's more, studies of mammals show a strong relationship between brain size and the rate of development, with larger-brained animals taking longer to reach adulthood. Humans are at the far end of this spectrum. If this theory is correct, and the development of large brains accounts for the teenage growth spurt, the origin of adolescence should have been with the evolution of our* own species (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthals, starting almost 200,000 years ago. The trouble is, some of the fossil evidence seems to tell a different story.

(C) The human fossil record is extremely sparse, and the number of fossilised children minuscule. Nevertheless, in the past few years anthropologists have begun to look at what can be learned of lives of our ancestors from these youngsters, of the most studied is the famous Turkana boy, an almost complete skeleton of Homo erectus f 1.6 million years ago found in Kenya in 1984. Accurately assessing how old someone is from their skeleton is a tricky business. Even with a modern human, you can only make a rough estimate based on the developmental stage of teeth and bones and the skeleton's general size.

(D) You need as many developmental markers as possible to get an estimate of age. The Turkana's teeth made him 10 or 11 years old. The features of his skeleton put him at 13, but he as tall as a modem 15-year-old. Susan Anton of New York University points to research by Margaret Clegg who studied a collection of 18th-century 19th-century skeletons whose ages at death were known. When she tried to age the skeletons Without checking the records, she found similar discrepancies to those of the Turkana boy. One 10-year-old boy, for example, had a dental age of 9, the skeleton of a 6-year-old but was tall enough to be 11. 'The Turkana kid still has a rounded skull, and needs more growth to reach the adult shape/ Anton adds. She thinks that Homo erectus already developed modern human patterns growth, with a late, if not quite so extreme, adolescent spurt. She believes Turkana boy was just about to enter it.

(E) If Anton is right, that theory contradicts the orthodox idea linking late growth with development of a large brain. Anthropologist Steven Leigh from the University of Illinois goes further. He believes the idea of adolescence as catchup growth does not explain why the growth rate increases so dramatically. He says that many apes have growth spurts in particular body regions that are associated with reaching maturity, and this makes sense because by timing the short but crucial spells of maturation to coincide with the seasons when food is plentiful, they minimise the risk of being without adequate food supplies while growing. What makes humans unique is that the whole skeleton is involved. For Leigh, this is the key.

(F) According to his theory, adolescence evolved as an integral part of efficient upright locomotion, as well as to accommodate more complex brains. Fossil evidence suggests that our ancestors first walked on two legs six million years ago. If proficient walking was important for survival, perhaps the teenage growth spurt has very ancient origins. While many anthropologists will consider Leigh's theory a step too far, he is not the only one with new ideas about the evolution of teenagers.

(G) Another approach, which has produced a surprising result, relies on the minute analysis of tooth growth. Every nine days or so the growing teeth of both apes and humans acquire ridges on their enamel surface. These are like rings in a tree trunk: the number of them tells you how long the crown of a tooth took to form. Across mammals' the rate at which teeth develop is closely related to how fast the brain grows and the age you mature. Teeth are good indicators of life history because thefr growth is less related to the environment and nutrition than is the growth of the skeleton.

(H) A more decisive piece of evidence came last year, when researchers in France and Spain published their findings from a study of Neanderthal teeth. Neanderthals had much faster tooth growth than erectus who went before them, and hence, possibly, a shorter childhood. Lead researcher Fernando Ramirez- Rozzi thinks Neanderthals died young-about 25 years old - primarily because of the cold, harsh environment they had to endure in glacial Europe. They evolved to grow up quicker than their immediate ancestors. Neanderthals and Homo erectus probably had to reach adulthood fairly quickly, without delaying for an adolescent growth spurt. So it still looks as though we are the original teenagers.

Questions 1-4: Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 1-4 on your answer sheet.

Q.1. In the first paragraph, why does the writer say ‘This is not merely an academic debated’?

(a) Anthropologists’ theories need to be backed up by practical research.

(b) There have been some important misunderstandings among anthropologists.

(c) The attitudes of anthropologists towards adolescence are changing.

(d) The work of anthropologists could inform our understanding of modem adolescence.

Q.2. What was Susan Anton’s opinion of the Turkana boy?

(a) He would have experienced an adolescent phase had he lived.

(b) His skull showed he had already reached adulthood

(c) His skeleton and teeth could not be compared to those from a more modem age.

(d) He must have grown much faster than others alive at the time.

Q.3. What point does Steven Leigh make?

(a) Different parts of the human skeleton develop at different speeds.

(b) The growth period of many apes is confined to times when there is enough food.

(c) Humans have different rates of development from each other depending on living conditions.

(d) The growth phase in most apes lasts longer if more food is available.

Q.4. What can we learn from a mammal's teeth?

(a) A poor diet will cause them to grow more slowly.

(b) They are a better indication of lifestyle than a skeleton

(c) Their growing period is difficult to predict accurately.

(d) Their speed of growth is directly related to the body’s speed of development.

Questions 5-10 Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 5-10 on your answer sheet, write YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this 5 It is difficult for anthropologists to do research on human fossil because they are so rare.

Q.6. Modem methods mean it is possible to predict the age of a skeleton with accuracy.

Q.7. Susan Anton’s conclusion about the Turkana boy reinforces an established idea.

Q.8. Steen Leigh’s ideas are likely to be met with disbelief by many anthropologists.

Q.9. Researchers in France and Spain developed a unique method of analyzing teeth.

Q.10. There has been too little research comparing the brains of Homo erectus and Neanderthals.

Questions 11-14 Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-G, below. Write the correct letter A-G, in boxesll-14 on your answer sheet.

Q.11. Until recently, delayed growth in humans until adolescence was felt to be due to

Q.12. In her research, Margaret Clegg discovered

Q.13. Steven Leigh thought the existence of adolescence is connected to

Q.14. Research on Neanderthals suggests that they has short lives because of

(a) inconsistencies between height, skeleton and dental evidence.

(b) the fact that human beings walk on two legs,

(c) the way teeth grew.

(d) a need to be dependent on others foe survival.

(e) difficult climatic conditions.

(f) increased quantities of food

(g) the existence of much larger brains than preciously

Section - 2

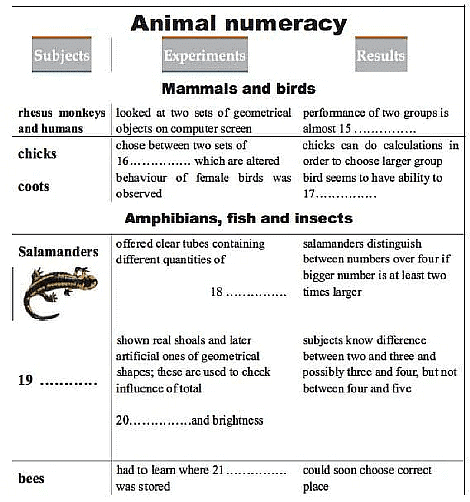

Numeracy: can animals tell numbers?

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 15—27, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

(A) Prime among basic numerical faculties is the ability to distinguish between a larger and a smaller number, says psychologist Elizabeth Brannon. Humans can do this with ease - providing the ratio is big enough - but do other animals share this ability? In one experiment, rhesus monkeys and university students examined two sets of geometrical objects that appeared briefly on a computer monitor. They had to decide which set contained more objects. Both groups performed successfully but, importantly, Brannon's team found that monkeys, like humans, make more errors when two sets of objects are close in number. The students' performance ends up looking just like a monkey's. It's practically identical, 'she says.

(B) Humans and monkeys are mammals, in the animal family known as primates. These are not the only animals whose numerical capacities rely on ratio, however. The same seems to apply to some amphibians. Psychologist Claudia Uller's team tempted salamanders with two sets of fruit flies held in clear tubes. In a series of trials, the researchers noted which tube the salamanders scampered towards, reasoning that if they had a capacity to recognise number, they would head for the larger number. The salamanders successfully discriminated between tubes containing 8 and 16 flies respectively, but not between 3 and 4, 4 and 6, or 8 and 12. So it seems that for the salamanders to discriminate between two numbers, the larger must be at least twice as big as the smaller. However, they could differentiate between 2 and 3 flies just as well as between 1 and 2 flies, suggesting they recognise small numbers in a different way from larger numbers.

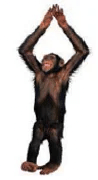

(C) Further support for this theory comes from studies of mosquitofish, which instinctively join the biggest shoal they can. A team at the University of Padova found that while mosquitofish can tell the difference between a group containing 3 shoal-mates and a group containing 4, they did not show a preference between groups of 4 and 5. The team also found that mosquitofish can discriminate between numbers up to 16, but only if the ratio between the fish in each shoal was greater than 2:1. This indicates that the fish, like salamanders, possess both the approximate and precise number systems found in more intelligent animals such as infant humans and other primates.

(D) While these findings are highly suggestive, some critics argue that the animals might be relying on other factors to complete the tasks, without considering the number itself. 'Any study that's claiming an animal is capable of representing number should also be controlling for other factors, ' says Brannon. Experiments have confirmed that primates can indeed perform numerical feats without extra clues, but what about the more primitive animals?

(E) To consider this possibility, the mosquitofish tests were repeated, this time using varying geometrical shapes in place of fish. The team arranged these shapes so that they had the same overall surface area and luminance even though they contained a different number of objects. Across hundreds of trials on 14 different fish, the team found they consistently discriminated 2 objects from 3. The team is now testing whether mosquitofish can also distinguish 3 geometric objects from 4.

(F) Even more primitive organisms may share this ability. Entomologist Jurgen Tautz sent a group of bees down a corridor, at the end of which lay two chambers - one which contained sugar water, which they like, while the other was empty. To test the bees' numeracy, the team marked each chamber with a different number of geometrical shapes - between 2 and 6. The bees quickly learned to match the number of shapes with the correct chamber. Like the salamanders and fish, there was a limit to the bees' mathematical prowess - they could differentiate up to 4 shapes, but failed with 5 or 6 shapes.

(G) These studies still do not show whether animals learn to count through training, or whether they are born with the skills already intact. If the latter is true, it would suggest there was a strong evolutionary advantage to a mathematical mind. Proof that this may be the case has emerged from an experiment testing the mathematical ability of three-and four-day-old chicks. Like mosquitofish, chicks prefer to be around as many of their siblings as possible, so they will always head towards a larger number of their kin. If chicks spend their first few days surrounded by certain objects, they become attached to these objects as if they were family. Researchers placed each chick in the middle of a platform and showed it two groups of balls of paper. Next, they hid the two piles behind screens, changed the quantities and revealed them to the chick. This forced the chick to perform simple computations to decide which side now contained the biggest number of its "brothers'. Without any prior coaching, the chicks scuttled to the larger quantity at a rate well above chance. They were doing some very simple arithmetic, claim the researchers.

(H) Why these skills evolved is not hard to imagine, since it would help almost any animal forage for food. Animals on the prowl for sustenance must constantly decide which tree has the most fruit, or which patch of flowers will contain the most nectar. There are also other, less obvious, advantages of numeracy. In one compelling example, researchers in America found that female coots appear to calculate how many eggs they have laid - and add any in the nest laid by an intruder - before making any decisions about adding to them. Exactly how ancient these skills are is difficult to determine, however. Only by studying the numerical abilities of more and more creatures using standardised procedures can we hope to understand the basic preconditions for the evolution of number.

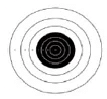

Questions 15-21: Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 15-21 on your answer sheet Answer the table below.

Questions 22-27: Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 22-27 on your answer sheet, write TRUE if the statement true FALSE if the statement false NOT GIVEN if the information not given in the passage

Q.22. Primates are better at identifying the larger of two numbers if one is much bigger than the other.

Q.23. Jurgen Tautz trained the insects in his experiment to recognise the shapes of individual numbers.

Q.24. The research involving young chicks took place over two separate days.

Q.25. The experiment with chicks suggests that some numerical ability exists in newborn animals.

Q.26. Researchers have experimented by altering quantities of nectar or fruit available to certain wild animals.

Q.27. When assessing the number of eggs in their nest, coots take into account those of other birds.

Section - 3

(A) A postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, O'Connell- Rodwell has come to Namibia's premiere wildlife sanctuary to explore the mysterious and complex world of elephant communication. She and her colleagues are part of a scientific revolution that began nearly two decades ago with the stunning revelation that elephants communicate over long distances using low-frequency sounds, also called infrasounds, that are too deep to be heard by most humans.

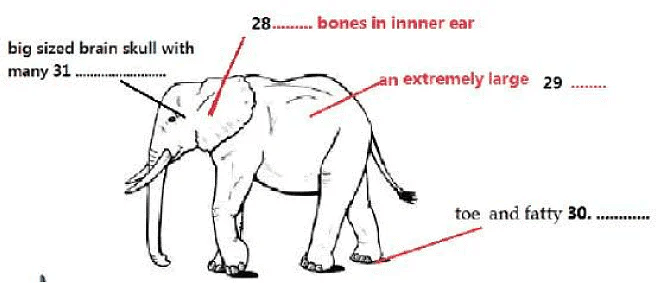

(B) As might be expected, the African elephant's ability to sense seismic sound may begin in the ears. The hammer bone of the elephant's inner ear is proportionally very large for a mammal, but typical for animals that use vibrational signals. It may therefore be a sign that elephants can communicate with seismic sounds. Also, the elephant and its relative the manatee are unique among mammals in having reverted to a reptilian-like cochlear structure in the inner ear. The cochlea of reptiles facilitates a keen sensitivity to idbrations and may do the same in elephants.

(C) But other aspects of elephant anatomy also support that ability. First, then enormous bodies, which allow them to generate low-frequency sounds almost as powerful as those of a jet takeoff, provide ideal frames for receiving ground vibrations and conducting them to the inner ear. Second, the elephant's toe bones rest on a fatty pad that might help focus vibrations from the ground into the bone. Finally, the elephant's enormous brain lies in the cranial cavity behind the eyes in line with the auditory canal. The front of the skull is riddled with sinus cavities that may function as resonating chambers for vibrations from the ground.

(D) How the elephants sense these vibrations is still unknown, but O'Connell- Rodwell who just earned a graduate degree in entomology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, suspects the pachyderms are "listening" with then trunks and feet. The trunk may be the most versatile appendage in nature. Its uses include drinking, bathing, smelling, feeding and scratching. Both trunk and feet contain two kinds of pressure-sensitive nerve endings—one that detects infrasonic vibrations and another that responds to vibrations with slightly higher frequencies. For O'Connell-Rodwell, the future of the research is boundless and unpredictable: "Our work is really at the interface of geophysics, neurophysiology and ecology," she says. "We're asking questions that no one has really dealt with before."

(E) Scientists have long known that seismic communication is common in small animals, including spiders, scorpions, insects and a number of vertebrate species such as white-lipped frogs, blind mole rats, kangaroo rats and golden moles. They also have found evidence of seismic sensitivity in elephant seals—2-ton marine mammals that are not related to elephants. But O'Connell-Rodwell was the first to suggest that a large land animal also is sending and receiving seismic messages. O'Connell-Rodwell noticed something about the freezing behavior of Etosha's six-ton bulls that reminded her of the tiny insects back in her lab. "I did my masters thesis on seismic communication in planthoppers," she says. "I'd put a male planthopper on a stem and play back a female call, and the male would do the same thing the elephants were doing: He would freeze, then press down on his legs, go forward a little bit, then freeze again. It was just so fascinating to me, and it's what got me to think, maybe there's something else going on other than acoustic communication."

(F) Scientists have determined that an elephant's ability to communicate over long distances is essential for its survival, particularly in a place like Etosha, where more than 2,400 savanna elephants range over an area larger than New Jersey. The difficulty of finding a mate in this vast wilderness is compounded by ... elephant reproductive biology. Females breed only when nestrus a period of sexual arousal that occurs every two years and lasts just a few days. "Females in estrus make these very low, long calls that bulls home in on, because it's such a rare event," O'Connell-Rodwell says. These powerful estrus calls carry more than two miles in the air and may be accompanied by long-distance seismic signals, she adds. Breeding herds also use low-frequency vocalizations to warn of predators. Adult bulls and cows have no enemies, except for humans, but young elephants are susceptible to attacks by lions and hyenas. When a predator appears, older members of the herd emit intense warning calls that prompt the rest of the herd to clump together for protection, then lee. In 1994, O'Connell-Rodwell recorded the dramatic cries of a breeding herd threatened by lions at Mushara. "The elephants got really scared, and the matriarch made these very powerful warning calls, and then the herd took off screaming and trumpeting," she recalls. "Since then, every time we've played that particular call at the water hole, we get the same response the elephants take off."

(G) Reacting to a warning call played hi the air is one thing, but could the elephants detect calls transmitted only through the ground? To find out, the research team in 2002 devised an experiment using electronic equipment that allowed them to send signals through the ground at Mushara. The results of our 2002 study showed US that elephants do indeed detect warning calls played through the ground," O'Connell-Rodwell observes. "We expected them to clump up into tight groups and leave the area, and that's in fact what they did. But since we only played back one type of call, we couldn't really say whether they were interpreting it correctly. Maybe they thought it was a vehicle or something strange instead of a predator warning."

(H) An experiment last year was designed to solve that problem by using three different recordings—the 1994 warning call from Mushara, an anti-predator call recorded by scientist Joyce Poole in Kenya and an artificial warble tone. Although still analyzing data from this experiment, O'Connell-Rodwell is able to make a few preliminary observations: "The data I've seen so far suggest that the elephants were responding like I had expected, when the '94 warning call was played back, they tended to clump together and leave the water hole sooner. But what's really interesting is that the unfamiliar anti-predator call from Kenya also caused them to clump up, get nervous and aggressively rumble—but they didn't necessarily leave. I didn't think it was going to be that clear cut.

Questions 28-31: Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 28-31 on your answer sheet.

Question 32-38: Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more three words or a number from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 32-38 on your answer sheet.

How the elephants sense these sound vibrations is still unknown, but O’Connell- Rodwell, a fresh graduate in entomology at the University of Hawaii, proposes that the elephants are “listening” with their 32_______ by two kinds of nerve endings—that responds to vibrations with both 33 _______frequency and slightly higher frequencies, o’Connell-Rodwell work is at the combination of geophysics, neurophysiology and 34_______and it also was the first to indicate that a large land animal also is sending and receiving 35 _______ O’Connell-Rodwell noticed the freezing behavior by putting a male planthopper communicative approach other than 36_______Scientists have determined that an elephant’s ability to communicate over long distances is essential, especially, when elephant herds are finding a 37_______ or are warning of predators. Finally, the results of our 2002 study showed US that elephants can detect warning calls played through the 38_______

Question 39-40: Choose the correct letter. A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 39-40 on your answer sheet.

Q.39. According the passage, it is determined that an elephant need to communicate over long distances for its survival

(a) When a threatening predator appears.

(b) When young elephants meet humans.

(c) When older members of the herd want to flee from the group.

(d) when a male elephant is in estrus.

Q.40. what is the author’s attitude toward the experiment by using three different recordings in the paragraph

(a) the outcome is definitely out of the original expectation

(b) the data can not be very clearly obtained

(c) the result can be somewhat undecided or inaccurate

(d) the result can be unfamiliar to the public.

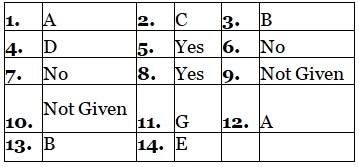

Answers

Section - 1 Section - 2

Section - 2

Section - 3

Section - 3