Peasants, Zamindars and the State Class 12 History

Introduction

Peasants formed the backbone of agricultural society in sixteenth and seventeenth-century India. Villages were the basic units where peasants performed essential farming tasks. Large areas of dry land, hills, and forests were unsuitable for cultivation, impacting available farmland. Primary sources like Mughal court chronicles, especially the Ain-i Akbari, and regional revenue records provide valuable insights into agrarian practices.

Peasants and Agricultural Production

- The village served as the fundamental unit of agricultural society, with peasants performing various seasonal tasks essential for farming.

- Large tracts of dry land, hilly regions, and substantial forest areas were not suitable for cultivation, impacting the available arable land.

- Primary sources for understanding agrarian history during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries include Mughal court chronicles, such as Ain-i Akbari, which meticulously recorded state arrangements.

- Detailed revenue records from regions like Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries provide valuable insights into agrarian practices.

- Extensive records from the East India Company offer useful descriptions of agrarian relations in eastern India, capturing conflicts between peasants, zamindars, and the state.

Looking for Sources

Primary Sources:

- Main sources of information are chronicles and documents from the Mughal court.

- One of the most significant chronicles was written by Akbar’s court historian, Abu’l Fazl.

- The Ain meticulously recorded state arrangements for ensuring cultivation, collecting revenue, and managing the relationship between the state and zamindars.

- The central aim was to present a vision of Akbar’s empire characterized by social harmony under a strong ruling class.

- Any challenge to Mughal authority was depicted as destined to fail.

- The Ain provides insights from the perspective of the ruling class, not the peasants.

Supplementary Sources:

- Detailed records from Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries provide additional context.

- Extensive records from the East India Company offer valuable descriptions of agrarian relations in eastern India.

Insights from Conflicts:

- Documentation of Conflicts: These sources record instances of conflicts between peasants, zamindars, and the state.

- Peasants' Perceptions: They offer insights into how peasants viewed their relationship with the state and their expectations of fairness.

Peasants and Their Land

- Common terms used for peasants were raiyat, muzarian, kisan, or asami.

- Two main types of peasants were khud-kashta (resident cultivators) and pahi-kashta (non-resident cultivators working on a contractual basis).

- Peasants typically owned small plots, with an average north Indian peasant possessing limited agricultural tools.

- Landownership was based on individual ownership, and the wealth of a peasant was often determined by the size of their land.

Irrigation and Technology

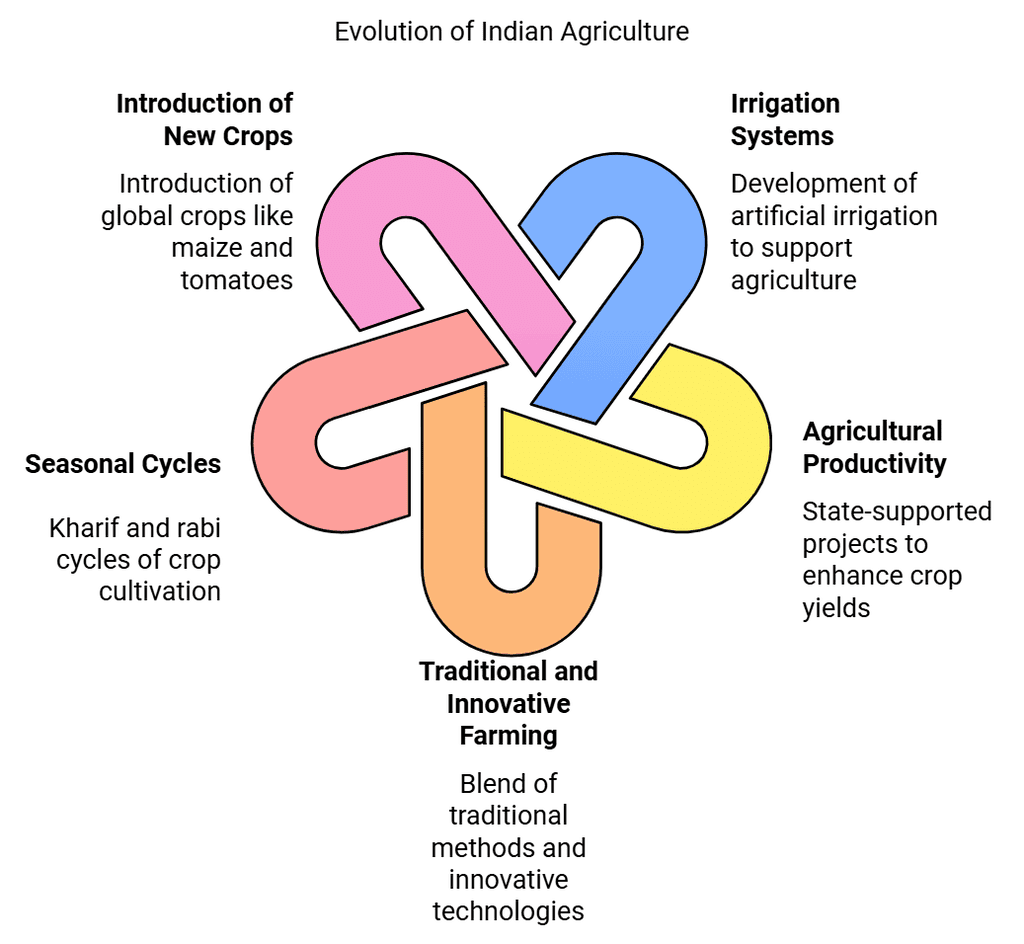

- Monsoons were crucial for Indian agriculture, but some crops required additional water, leading to the development of artificial irrigation systems.

- The state supported irrigation projects to enhance agricultural productivity.

- Despite being labor-intensive, peasants incorporated technologies that utilized cattle energy, showcasing a blend of traditional and innovative approaches to farming.

Abundance of Crops

- Agriculture revolved around two major seasonal cycles - kharif (autumn) and rabi (spring).

- The seventeenth century saw the introduction of new crops from different parts of the world.

- For instance, maize from Africa and Spain became a major crop in western India.

- Vegetables like tomatoes, potatoes, and chillies were introduced from the New World.

- Fruits like pineapple and papaya contributed to the diversity of crops in the Indian subcontinent.

The Village Community

Individual ownership of lands existed alongside collective village community ownership.

The village community consisted of three main elements:

1. Cultivators

2. Panchayat (assembly of elders)

3. Village headman (muqaddam or mandal)

Village Headman

Village Headman

Caste and the Rural Milieu

- Deep inequities based on caste and caste-like distinctions resulted in a highly heterogeneous group of cultivators.

- Despite abundant cultivable land, certain caste groups were assigned menial tasks, such as menials or agricultural laborers (majur).

- In Muslim communities, menials like halalkhoran (scavengers) were often located outside the village boundaries.

- A direct correlation existed between caste, poverty, and social status, especially in the lower strata of society.

Panchayats and Headman

- An assembly of elders, headed by a headman (muqaddam or mandal), was responsible for various community matters.

- Headmen held office based on the confidence of village elders, and they could be dismissed if that confidence was lost.

- The main role of the headman was to oversee the preparation of village records, with help from the accountant or patwari of the panchayat.

- The panchayat derived funds from contributions made by individuals to a common financial pool.

- One crucial function of the panchayat was to ensure the maintenance of caste boundaries within the village.

- Panchayats had the authority to levy fines and impose serious punishments, including expulsion from the community.

- Each caste or jati also had its own jati panchayat.

- Panchayats held significant power in rural society. For instance, in Rajasthan, where jati panchayats handled civil disputes, land claims, marriage norms, and ritual precedence. The state usually respected their decisions, except in criminal cases.

- Archival records from Rajasthan and Maharashtra show villagers, often from lower castes, petitioning against high taxes or forced labor by elite groups. These petitions argued for the basic right to survival, which they believed was protected by custom.

- The panchayat served as a court of appeal for justice.

- In disputes, panchayats often recommended compromise, but when this failed, peasants resisted by deserting villages, using the availability of uncultivated land and competition for labor as leverage.

Village Artisans

- The distinction between artisans and peasants was fluid, as many groups performed tasks related to both agriculture and crafts.

- Cultivators and their families engaged in craft production, including dyeing, textile printing, baking, pottery, and the making/repairing of agricultural implements.

- Village artisans, such as potters, blacksmiths, carpenters, barbers, and goldsmiths, provided specialized services in exchange for compensation, often in the form of a share of the harvest or land allotments. In Maharashtra such lands became the artisans’ miras or watan – their hereditary holding.

- Another system involved artisans and peasant households negotiating payment, often through goods-for-services exchanges.

- Eighteenth-century records show zamindars in Bengal compensating blacksmiths, carpenters, and goldsmiths with a small daily allowance and diet money. This was later known as the jajmani system, though the term was not used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

A "Little Republic" ?

- Some British officials in the nineteenth century perceived the village as a "little republic", where community members shared resources and labor collectively.

- However, this perception did not reflect rural egalitarianism, as deep inequities persisted based on caste and gender distinctions.

Women in Agrarian Society

- Women and men often worked side by side in the fields, blurring the lines between home and the outside world.

- However, there were still biases against women due to their biological roles.

- Women were vital in tasks like spinning yarn, working with clay in pottery, and embroidery.

- They were seen as essential not just for their work but also for having children in a society that relied heavily on labor.

- Social norms placed men as heads of households, leading to strict control over women by male relatives and the community.

- Artisanal tasks like spinning yarn, sifting and kneading clay for pottery, and embroidery heavily relied on female labor. As products became more commercialized, the demand for women’s work increased.

- Documents from Western India (Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra) show women petitioning village panchayats for justice. Common complaints included husbands' infidelity or neglect of the family by the male head, the grihasthi. While male infidelity wasn't always punished, authorities intervened to ensure the family was provided for.

- Often, women's names were left out of records, identifying them only as the mother, sister, or wife of the male head.

- Among the landed gentry, women had the right to inherit property. In Punjab, women, including widows, were active in the rural land market, selling property they inherited. Both Hindu and Muslim women inherited zamindaris, which they could sell or mortgage.

- Women zamindars were present in eighteenth-century Bengal, with one of the most notable zamindaris, Rajshahi, being led by a woman.

Bride-Price vs Dowry: Marriages in many rural communities required the payment of bride-price to the bride's family instead of dowry.

Forests and Tribes

Beyond Settled Villages

Forests and Scrublands:

- Rural India included vast forests and scrublands in regions like eastern, central, and northern India, Jharkhand, the Western Ghats, and the Deccan plateau.

- Forests covered about 40% of the land, according to contemporary sources.

Forest Dwellers (Jangli):

- "Jangli" referred to people living in forests who engaged in gathering forest produce, hunting, and shifting agriculture.

- Activities varied seasonally; for example, the Bhils collected forest produce in spring, fished in summer, cultivated during monsoons, and hunted in autumn and winter.

- Mobility was a key feature of these tribes.

State’s Perspective:

- The state viewed forests as refuges for rebels and troublemakers.

- Babur noted that jungles provided defense, making inhabitants rebellious and resistant to taxes.

Inroads into Forests

State and Elephants:

- The state required elephants for the army, often levying them as tributes (peshkash) from forest people.

- Hunting expeditions allowed emperors to travel and address grievances, symbolizing the state's concern for all subjects.

Commercial Agriculture:

- Increased demand for forest products like honey, beeswax, and gum lac, with gum lac becoming a major export.

- Elephants were also captured and sold, and trade often involved barter.

Social Changes:

- Tribal leaders became zamindars or kings, requiring armies for control.

- In regions like Sind, tribes had substantial military forces, and in Assam, the Ahom kings demanded military service in exchange for land.

- New cultural influences, such as sufi saints (pirs), contributed to the gradual acceptance of Islam among agricultural communities in newly colonized areas.

The Zamindars

- Zamindars were a class in the countryside living off agriculture but not directly involved in production processes.

- They were landed proprietors enjoying social and economic privileges due to their superior status in rural society.

- Caste contributed to the high status of zamindars. Another factor was their performance of specific services (khidmat) for the state.

- Zamindars held extensive personal lands known as milkiyat.

- They had the power to collect revenue on behalf of the state.

- Zamindars often had fortresses (qilachas) and an armed contingent, including cavalry, artillery, and infantry.

- Zamindars spearheaded the colonization of agricultural land, settling cultivators by providing means of cultivation and cash loans.

- Despite being viewed as exploitative, the relationship between zamindars and peasants often had elements of reciprocity, paternalism, and patronage.

Land Revenue System

- Land revenue was vital for the Mughal Empire's economy.

- The diwan supervised the fiscal system, and revenue officials and record keepers played key roles.

- Detailed data on agricultural lands and production was collected before tax assessment.

- Revenue collection involved assessing the land (jama) and collecting taxes (hasil), with flexibility in cash or kind payments.

- The amil-guzar, or revenue collector, encouraged cultivators to pay in cash, though Akbar allowed payment in kind for flexibility.

- Efforts to measure land were ongoing, but large forest areas remained unmeasured.

Flow of Silver

- The Mughal Empire consolidated resources and power from Ming (China), Safavid (Iran), and Ottoman (Turkey) during the 16th and 17th centuries, contributing to its economic strength.

- Exploratory voyages and the opening up of the New World led to a substantial expansion of trade between Asia, particularly India, and Europe.

- The increased trade resulted in significant amounts of silver bullion flowing into Asia, with a large portion gravitating towards India. The availability of silver became a stable aspect of the metal currency during this period.

The Ain-i Akbari of Abu’l Fazl Allami

Compiled by Abu’l Fazl under Emperor Akbar's direction, completed in 1598 after five revisions, Ain -i Akbari was project of classification. Part of the Akbar Nama, focused on history, the Ain-i Akbari serves as a compendium of imperial regulations and a gazetteer.

It Comprises five books (daftars):

First book (manzil-abadi): Concerns the imperial household.

Second book (sipah-abadi): Covers military and civil administration.

Third book (mulk-abadi): Provides detailed fiscal information, including revenue rates and administrative divisions.

Fourth and fifth books: Discuss religious, literary, and cultural traditions of India, along with Akbar’s sayings.Offers intricate accounts of court organization, administration, army, revenue sources, provincial layout, and cultural practices across Akbar’s empire.

Includes quantitative details such as revenue assessments, geographic profiles, and economic statistics down to the sub-district level (sarkars, parganas, and mahals).

Revised multiple times for accuracy, incorporating verified oral testimonies and replicating numeric data in words to minimize transcription errors.

Despite richness, some areas lack uniform data collection (e.g., caste compositions in Bengal and Orissa). Fiscal data is detailed, but information on prices and wages is limited to specific areas near Agra.

Offers insights into Mughal governance and society, although some errors in totaling and data collection discrepancies exist.

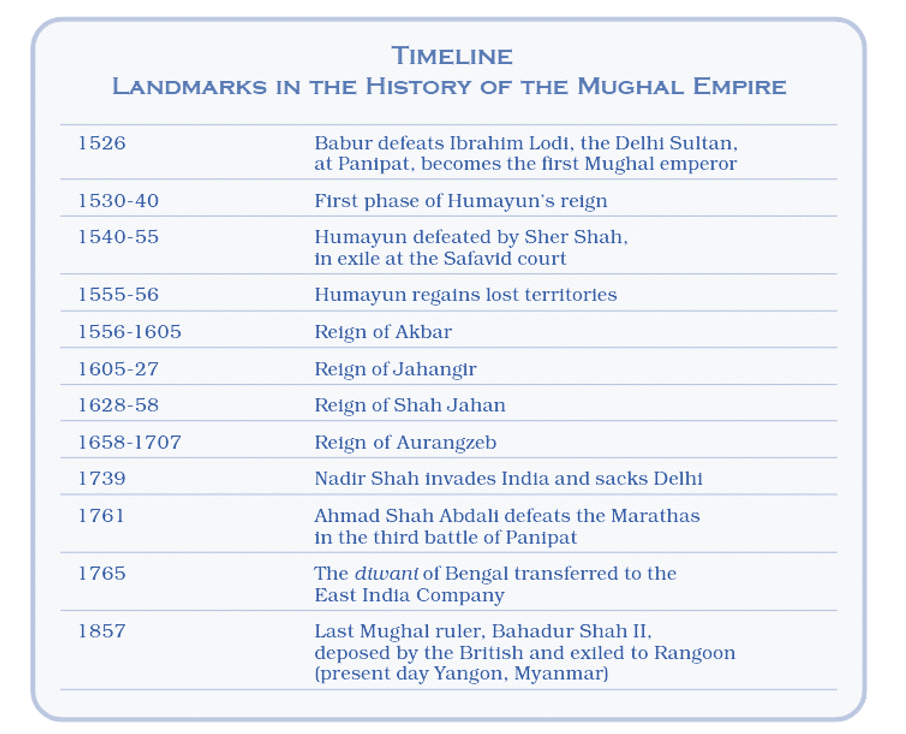

Timeline

Landmarks in the History of the Mughal Empire

Landmarks in the History of the Mughal Empire

Conclusion

The agrarian society in 16th and 17th century India was rooted in village life, with peasants performing seasonal tasks and cultivating individual lands. Sources like Ain-i-Akbari, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan records provide insights. Villages had panchayats, led by a muqaddam, addressing issues and preserving caste norms. Women's roles varied, with high mortality rates and instances of inheritance. Forests and tribes coexisted, facing the impact of Mughal hunting and commercial agriculture. Zamindars, holding milkiyat lands, played a pivotal role, collecting revenue for the state. Ain-i-Akbari documented the empire's administration and societal aspects, serving as a benchmark for studying 17th-century India.

|

30 videos|274 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Peasants, Zamindars and the State Class 12 History

| 1. What role did peasants play in agricultural production during the time discussed in the article? |  |

| 2. How did the village community operate within the agrarian society? |  |

| 3. What was the significance of women in agrarian societies according to the article? |  |

| 4. How did the zamindars influence the land revenue system? |  |

| 5. What insights does the Ain-i Akbari provide about the socio-economic structure of the time? |  |