Understanding Partitions Class 12 History

| Table of contents |

|

| Historical Background of Partition |

|

| Why and How Did Partition Happen? |

|

| The Withdrawal of Law and Order |

|

| Help, Humanity, and Harmony |

|

Historical Background of Partition

Separate Electorate (1909)

- Background: The Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909 introduced separate electorates based on religion, primarily aiming to provide political representation to various communities in British India. This system allowed Muslims to vote for Muslim candidates and Christians for Christian candidates, fostering religious divisions in the political landscape.

- Impact: The introduction of separate electorates deepened communal divisions, as it laid the groundwork for politicians to exploit religious identities for electoral gains. This move marked an early step in the politicization of religion in the Indian subcontinent.

Colonial Government Policies (1919)

- Background: The colonial government's repressive measures, particularly the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919, where British troops killed hundreds of unarmed Indian civilians, led to widespread discontent. The government's handling of the aftermath, including the implementation of the repressive Rowlatt Act, further fueled anti-British sentiments.

- Impact: The resentment against colonial rule became a unifying factor for Indians across religious lines. However, the divisive policies of the British also contributed to the rise of communal tensions, as different communities responded differently to colonial actions.

Consolidation of Communal Identities (1920s-1930s)

- Events:

- Music before Ramjasid: The playing of music before mosques became a contentious issue, leading to tensions between Hindus and Muslims. It symbolized the growing cultural and religious divides.

- Cow Protection Movement: The movement, fueled by Hindu sentiments against cow slaughter, further polarized communities and intensified religious identities.

- Shuddhi Movement of Arya Samaj: Aimed at reconverting converted Hindus back to Hinduism, this movement added to the communal discord by challenging the religious demography.

Arya Sama

Arya Sama

- Impact: These events heightened religious sensitivities, contributing to the solidification of communal identities. The reaction from different communities exacerbated tensions and created an environment conducive to further divisions.

- Events:

Spread of Tabligh and Tanzim (Propaganda and Organization)

- Background: The rapid dissemination of religious propaganda and organizational efforts by various religious groups, particularly among Muslims, heightened apprehensions among other religious communities.

- Impact: The fear and mistrust generated by these activities added to the communal tensions. The perception of communities as threats to each other's existence became more pronounced, leading to a growing sense of insecurity and hostility.

Communal Riots

- Background: Communal riots during this period, often triggered by religious or political events, deepened the rifts between communities. The violence and loss of life reinforced negative perceptions and fueled further animosity.

- Impact: Communal riots not only resulted in immediate human suffering but also left lasting scars on inter-community relations. They exacerbated existing tensions and contributed to an environment where the idea of a separate nation for Muslims gained traction.

Why and How Did Partition Happen?

1. Provincial Elections of 1937 and Congress Ministries

The provincial elections of 1937 were a significant political event in British India. The Congress Party, led by leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, won the majority in five provinces and formed the government in seven out of eleven provinces. This marked a significant shift in Indian politics as Congress took charge of several key regions.

In the reserved constituencies, which were set aside for marginalized groups, both Congress and the Muslim League faced challenges. The Muslim League performed poorly in these areas, leading to a sense of disillusionment among its members.

In the United Province (present-day Uttar Pradesh), the Muslim League expressed interest in forming a coalition government with Congress. However, Congress, having an absolute majority, rejected the proposal. This rejection fueled a perception among Muslim League members that they would be politically marginalized as a minority.

Provincial election of 1937

Provincial election of 1937

2. League's Social Expansion and Congress Failure

The 1930s saw the Muslim League actively working to expand its social base, recognizing its limited support. The League aimed to strengthen its presence in Muslim-dominated areas to become a more influential political force.

Congress and its ministries, despite their dominance, failed to effectively counter the propaganda and divisive tactics employed by the Muslim League. The failure to win over the Muslim masses contributed to the deepening divide between Hindus and Muslims.

The emergence and growth of organizations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Hindu Mahasabha played a role in exacerbating religious differences. These groups focused on Hindu nationalist ideologies, further polarizing communities along religious lines.

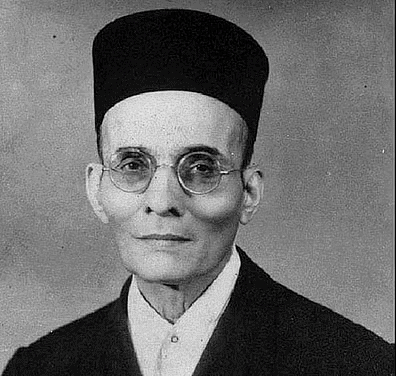

Veer Savarkar of Hindu Mahasabha

Veer Savarkar of Hindu Mahasabha

3. The 'Pakistan' Resolution (1940)

On March 23, 1940, the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, passed the Lahore Resolution, often referred to as the 'Pakistan' Resolution. This resolution demanded autonomy for Muslim-majority areas within the subcontinent.

Notably, the resolution did not explicitly mention the creation of a separate nation or partition. Instead, it emphasized the idea of Muslim-majority regions having a measure of self-rule.

4. Suddenness of Partition

The demand for Pakistan, as articulated in the 1940 resolution, did not initially represent a clear and unequivocal call for a separate nation. Some leaders, including Jinnah, may have seen it as a negotiating tool to secure political concessions for Muslims.

The swift transition from the demand for autonomy to the actual partition within seven years was surprising. The factors contributing to this abrupt shift include changing political dynamics, communal tensions, and the failure of negotiations between different parties.

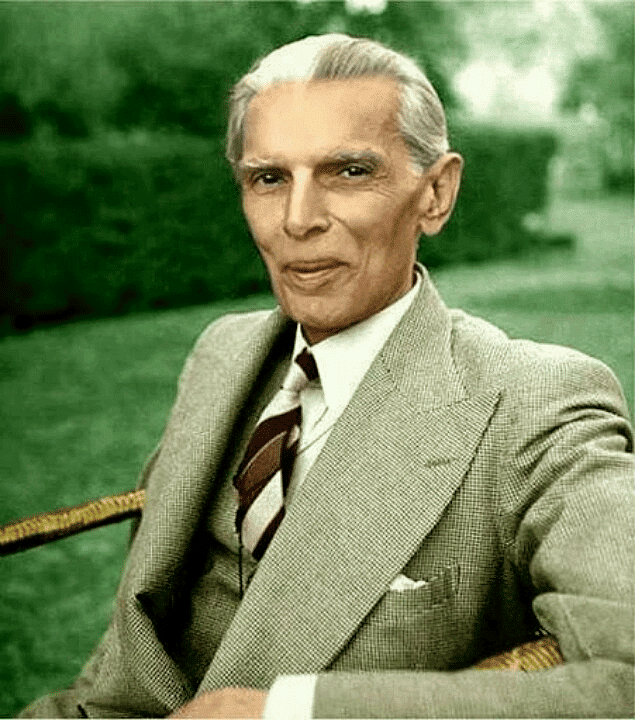

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

5. Post-War Developments (1945-1946)

After World War II, discussions between the British, Congress, and the Muslim League took place to determine the future political structure of India. However, these negotiations faced challenges due to Jinnah's steadfast demands regarding representation and communal issues.

In the 1946 provincial elections, Congress performed well in general constituencies, while the Muslim League secured a significant majority of Muslim votes. This electoral success strengthened the League's position as the primary political representative of Muslims.

The League's dominance in the reserved Muslim constituencies further solidified its claim as the leader of Muslim interests.

Question for Chapter Notes: Understanding PartitionsTry yourself:What was the outcome of Jinnah's theory of two states based on religion?View Solution

6. A Possible Alternative to Partition (Cabinet Mission, 1946)

The Cabinet Mission, comprising British officials, proposed a political framework for India in 1946. The plan suggested a united India with a three-tier confederation, categorizing provinces into sections based on religious majority.

Although initially agreed upon, disagreements arose over the compulsory nature of grouping and the right to secede. The Muslim League insisted on the right to secede, while Congress favored giving provinces the choice to join the groups voluntarily.

These disagreements eventually led to the breakdown of talks, leaving the issue of a united India unresolved.

7. Towards Partition (1946-1947)

After the withdrawal of the Cabinet Mission, the Muslim League, under Jinnah's leadership, decided to resort to direct action to press for its demand for Pakistan. August 16, 1946, was declared "direct action day," leading to widespread riots, particularly in Calcutta and other parts of Northern India.

The communal violence during this period heightened tensions between Hindus and Muslims, making the prospect of a united India more challenging.

In March 1947, Congress reluctantly accepted the division of Punjab and Bengal along religious lines, marking a significant step towards the eventual partition.

Calcutta riots of 1946

Calcutta riots of 1946

8. Opposition to Partition

While Congress leaders sensed the inevitability of partition after the failed negotiations, figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan continued to oppose the idea. They viewed partition as tragic but avoidable, emphasizing the need for communal harmony and a united India.

Despite their opposition, the communal violence and political circumstances eventually led to the partition of British India into the independent nations of India and Pakistan in 1947.

The Withdrawal of Law and Order

1. Introduction

- In 1947, large-scale bloodshed and violence engulfed the Indian subcontinent, leading to the collapse of the governance structure and a complete loss of authority.

- British officials were hesitant to make decisions as they were preparing to leave India, contributing to the vacuum in law and order.

- The situation worsened as communal tensions escalated, with soldiers and policemen abandoning their professional commitments and siding with their co-religionists, attacking members of other communities.

2. The One-Man Army

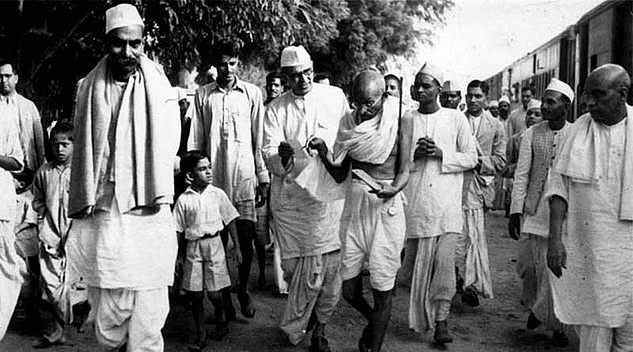

Except for Mahatma Gandhi, top leaders were engaged in negotiations regarding Independence.

Indian Civil Servants in affected areas were concerned for their safety.

Gandhi took bold efforts to restore peace by touring violence-stricken areas, including Noakhali in East Bengal, riot-torn Calcutta, and Delhi.

He encouraged mutual trust and protection among different religious communities, urging Hindus and Sikhs in Delhi to safeguard Muslims and assuring the safety of Hindus in East Bengal.

Gandhi embarked on a fast to bring about a change in people's hearts and end communal violence.

The fast had a profound impact, leading people to reflect on the harm done to other communities.

Unfortunately, the massacre only ended with the martyrdom of Gandhi.

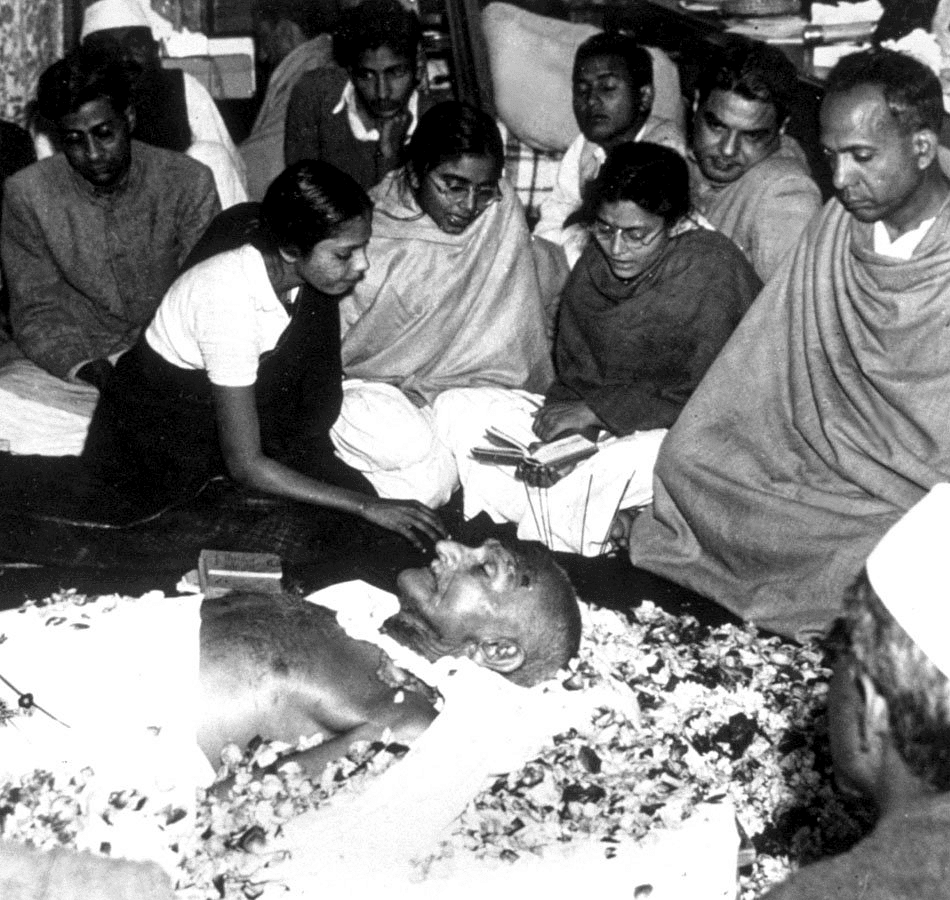

Last rites of Gandhiji

Last rites of Gandhiji

3. Gendering Partition

Women suffered immensely during the partition, facing atrocities such as rape, abduction, and forced settlement in unfamiliar circumstances.

Government responses lacked understanding of emotional trauma, and women were sometimes forcefully separated from their new relatives without consultation, undermining their rights.

Notions of honor were tied to masculinity, often defined by ownership of women and land. The belief was that virility lay in the ability to protect these possessions from outsiders.

Men, fearing for the safety of their women, sometimes resorted to killing them to prevent violation by the enemy.

Instances, such as 90 Sikh women voluntarily jumping into a well in Rawalpindi to protect themselves, were seen as acts of martyrdom.

The notion that men had to courageously accept women's decisions, and in some cases even persuade them to sacrifice themselves, prevailed during that time.

4. Regional Variations

The partition led to mass displacement and loss of lives, particularly in Punjab, where Hindu and Sikh populations moved from Pakistani to Indian territories, and Punjabi Muslims migrated to Pakistan from Indian regions.

Punjab witnessed agonizing events such as looting, killings, abductions, and rapes, resulting in large-scale massacres.

Bengal, in contrast, experienced less concentrated suffering as people moved across porous borders, and there was not a total displacement of Hindu and Muslim populations.

In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Hyderabad, some Muslim families migrated to Pakistan during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Question for Chapter Notes: Understanding PartitionsTry yourself:What is the main benefit of oral histories in understanding historical events?View Solution

5. Jinnah's Theory and the Creation of Bangladesh

- Jinnah's theory of two states based on religion failed when East Bengal separated from West Pakistan and became an independent country, Bangladesh, in 1971.

- This marked a significant divergence from the initial idea of creating two separate states for Muslims in the subcontinent.

6. Persecution and Targeting of Women

- In both Punjab and Bengal, women and girls were prime targets of persecution during the partition.

- Attackers treated women's bodies as territories to be conquered, and the violation of women from different communities was seen as a dishonor to the entire community.

- The discourse surrounding women became intertwined with the broader issues of honor and community identity during this tumultuous period.

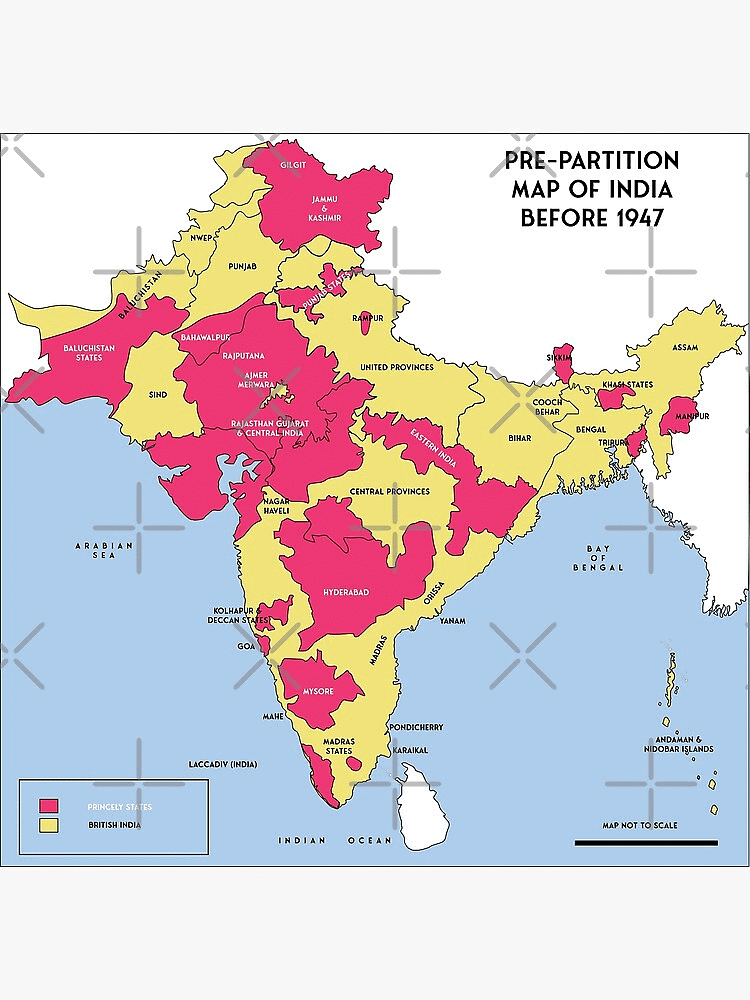

pre-partition Indian map

pre-partition Indian map

Help, Humanity, and Harmony

1. Introduction

- The history of help and humanity is found beneath the debris of violence and pain during the partition.

- Stories exist of people making extra efforts to assist victims of the partition, showcasing caring, sharing, and empathy.

- Examples like Khushdeva Singh, a Sikh doctor, who helped migrants from all communities during the partition, providing shelter, food, and security.

2. Oral Testimonies and History

- Oral narratives, memoirs, diaries, and family histories play a crucial role in understanding the suffering during the partition.

- Lives changed drastically between 1946-50, causing immense psychological, emotional, and social pain.

- Oral testimonies provide detailed insights into experiences and memories, enabling historians to write rich and vivid accounts of people's suffering and anguish.

3. Official Records vs. Oral Histories

- Official records focus on policy matters and high-level government decisions during the partition.

- Oral histories shed light on the experiences of the poor and powerless, highlighting significant help and empathy extended by people in easing the lives of affected individuals.

4. Challenges of Oral History

- Some historians doubt oral history, citing its lack of concreteness and chronology.

- Critics argue that oral histories might touch tangential issues and not provide an overall bigger picture.

- The reliability of oral histories can be examined by corroborating evidence from other sources.

5. Importance of Oral History

- Oral histories explore the experiences of individuals often ignored in mainstream historical narratives.

- They reveal the human side of historical events and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of people's experiences.

- Oral histories, while potentially lacking in availability and reliability, offer a unique perspective that complements official records.

6. Challenges Faced by Oral Historians

- Oral historians face the challenge of shifting actual experiences from the web of constructed memories.

- The availability and willingness of affected people to share their sufferings with strangers pose obstacles for oral historians.

- Despite challenges, oral history remains a valuable tool in capturing the nuanced and personal aspects of historical events such as the partition.

|

32 videos|284 docs|31 tests

|

FAQs on Understanding Partitions Class 12 History

| 1. What was the historical background of the Partition? |  |

| 2. Why did the Partition happen? |  |

| 3. How did the Partition happen? |  |

| 4. What role did the withdrawal of law and order play in the Partition? |  |

| 5. How did the concepts of help, humanity, and harmony relate to the Partition? |  |