Unit 3: Price Output Determination under Different Market Forms Chapter Notes | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

Perfect Competition

Features of Perfect Competition1. Large Number of Buyers and Sellers: In a perfectly competitive market, there are many buyers and sellers. No single buyer or seller can influence the price because their individual share of the market is too small.

2. Homogeneous Products: The products offered by all sellers are identical and of the same quality. This means that buyers cannot tell the difference between products from different sellers, and all goods sell at the same price.

3. Perfect Information: All consumers have complete information about the prices and products available in the market. This ensures that they can make informed decisions and helps maintain uniform pricing.

4. Freedom of Entry and Exit: Firms can freely enter or exit the market without facing legal or market-related barriers. This means that if a new firm sees a profit opportunity, it can start producing without any special costs or difficulties. Similarly, if a firm is not making a profit, it can exit the market easily.

5. Absence of Monopoly: In a perfectly competitive market, there is no element of monopoly. This means that no single firm has significant control over the market, and business combinations that create a monopoly are not possible.

6. Price Taker: Individual firms are price takers, meaning they accept the market price as given and cannot set their own prices. If a firm tries to charge a higher price, it will lose customers to competitors.

7. Perfect Mobility of Factors: The factors of production, such as labor and capital, can move freely in and out of the industry. This ensures that resources are allocated efficiently where they are most needed.

8. No Government Intervention: There is no government intervention in the market, such as price controls or subsidies, which could distort competition.

9. Normal Profit in the Long Run: In the long run, firms in a perfectly competitive market earn normal profits, which means they cover their costs but do not make excessive profits. This is because the freedom of entry and exit ensures that any economic profits attract new firms, driving down prices and profits.

Examples of Perfect Competition

- Agricultural Markets: Markets for common agricultural products like wheat, rice, and corn often exhibit characteristics of perfect competition. Multiple farmers sell identical products, and buyers have access to information about prices from various sellers.

- Stock Market: The stock market can be considered a perfectly competitive environment where numerous buyers and sellers trade shares of companies. Stocks of large companies often have homogeneous characteristics, and information about prices is readily available.

- Online Retail Platforms: E-commerce platforms where multiple sellers offer identical products, such as electronics or clothing, can also reflect perfect competition. Buyers can easily compare prices and product details from various sellers, leading to uniform pricing.

- Knowledge of Market Conditions: In a perfectly competitive market, both buyers and sellers have complete knowledge of the market conditions. This means they are aware of all relevant information necessary for their decisions, such as: (a) Stock Levels: The quantities of goods available in the market. (b) Product Nature: The characteristics and quality of the products. (c) Transaction Prices: The prices at which buying and selling transactions are taking place.

- Transaction Costs: Perfectly competitive markets have very low transaction costs. This implies that buyers and sellers do not incur significant expenses or time in finding each other and completing transactions.

- Price Takers: In a situation of perfect competition, all firms are price takers. This means that individual firms have to accept the price determined by the market forces of total demand and total supply. This principle applies to consumers as well. (a) Price Taking: When there is perfect knowledge and mobility in the market, if any seller attempts to raise their price above the market level, they will lose customers.

Examples of Near-Perfect Competition: While perfect competition is often considered a theoretical ideal, there are real-world examples that come close to this condition, such as:

(a) Agricultural Products: Markets for certain agricultural goods where many sellers offer similar products.

(b) Financial Instruments: Trading in stocks, bonds, and foreign exchange where numerous buyers and sellers operate.

(c) Precious Metals: Markets for gold, silver, and platinum where these metals are traded under competitive conditions.

Price Determination under Perfect Competition

Equilibrium of the Industry:

- In economic terms, an industry comprises numerous independent firms, each producing a homogeneous product. This similarity fuels competition among different units.

- The industry reaches equilibrium when its total output matches total demand, resulting in an equilibrium price. A firm is considered in equilibrium when it maximizes profits, with no reason to alter production levels.

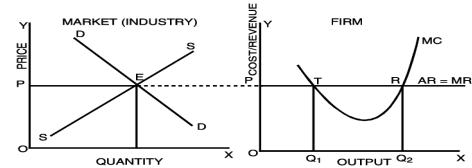

Equilibrium Price Determination:

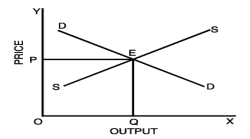

- Under competitive conditions, the equilibrium price for a product is set by the interaction of demand and supply forces.

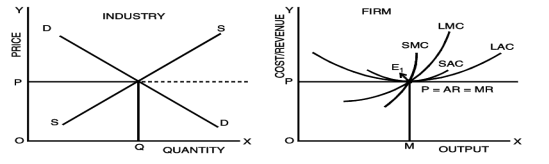

Equilibrium of the Competitive Industry

- Equilibrium Price (OP). The price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied.

- Equilibrium Quantity (OQ). The quantity sold at the equilibrium price.

- At this price, both buyers and sellers are satisfied, with no excess demand or supply.

- If the price were set higher or lower, or if the quantities differed from demand, equilibrium would be disrupted.

Equilibrium of the Firm:

- A firm is in equilibrium when it achieves maximum profit, producing what is known as equilibrium output.

- In this state, the firm has no reason to alter its production levels, either increasing or decreasing them.

- Firms in a competitive market act as price-takers because they produce identical products and cannot influence prices individually.

- They must accept the market price set by the overall demand and supply for their product.

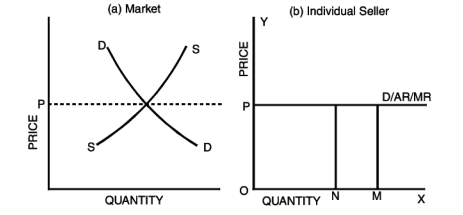

The Firm's Demand Curve under Perfect Competition

- The market price (OP) is determined by the total demand and supply in the industry.

- Individual firms must accept this price and cannot set it themselves.

- Firms cannot raise the price above OP because they would lose customers to competitors.

- Similarly, they do not lower the price below OP since there is no incentive to do so.

- Instead, they aim to sell as much as possible at the price of OP.

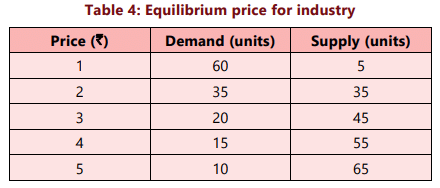

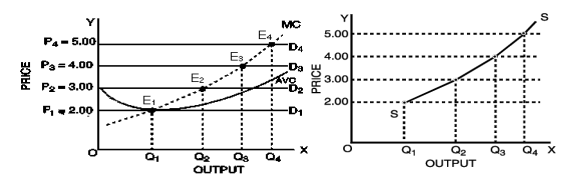

In a perfectly competitive market, the price line (P-line) acts as the demand curve for individual firms. Since these firms are price takers, their demand curve is represented by a horizontal line at the market price set by the industry. This means that the demand curve for each firm is perfectly elastic, allowing them to sell any quantity of output along this price line. Because the price is given, a competitive firm must adjust its output to match the market price to maximize profit. For example, in a scenario where the industry’s demand and supply schedules indicate an equilibrium price of ₹2 per unit, individual firms, like Firm X, would accept this price and sell varying quantities at it.

Because the price is given, a competitive firm must adjust its output to match the market price to maximize profit. For example, in a scenario where the industry’s demand and supply schedules indicate an equilibrium price of ₹2 per unit, individual firms, like Firm X, would accept this price and sell varying quantities at it.

Firm X’s performance at this price point shows that its total revenue, average revenue, and marginal revenue are all equal to ₹2. This illustrates that in a perfectly competitive market, a price-taking firm’s average revenue, marginal revenue, and price are the same. Consequently, when the firm sells an additional unit, its total revenue increases by the amount equal to the price.

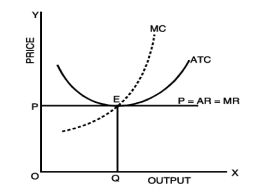

Conditions for Equilibrium: To achieve equilibrium, a firm in a competitive market must satisfy two conditions: (a) Marginal Revenue Equals Marginal Cost (MR = MC): If MR is greater than MC, the firm should increase production to maximize profits. Conversely, if MR is less than MC, the firm needs to reduce output because the cost of producing an additional unit exceeds the revenue it generates. Profits are maximized when MR = MC. (b) Marginal Cost Equals Price (MC = P): Since the demand curve for a competitive firm is horizontal, MR equals price (P). Therefore, the firm should choose its output level where marginal cost equals price. This simplifies the profit maximization rule for perfectly competitive firms.

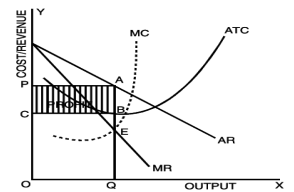

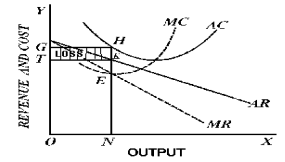

Short-Run Profit Maximization by a Competitive Firm

1. Conditions for Equilibrium:

- The MC (Marginal Cost) curve must cut the MR (Marginal Revenue) curve from below.

- This indicates that the MC curve should have a positive slope.

2. Short-Run Output Decision:

- In the short run, a firm operates with a fixed amount of capital and needs to determine the levels of its variable inputs to maximize profit.

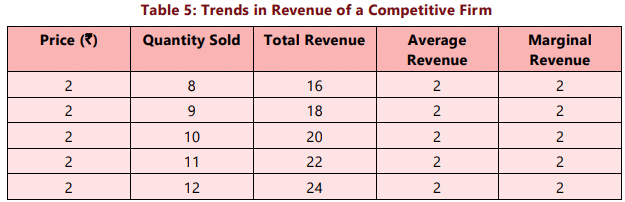

3. Market Price and Demand:

- The intersection of the industry demand (DD) and supply (SS) curves determines the market price (OP) at point E.

- Firms in a perfectly competitive industry accept the OP price as given, leading to a perfectly elastic demand (average revenue) curve at P.

4. Marginal Revenue:

- Since all units are priced at the same level, MR is a horizontal line equal to the AR line.

5. Cutting Points of MC and MR:

- The MC curve cuts the MR curve at two points: T and R.

- At point T, the MC curve cuts the MR curve from above, indicating that it is not a point of equilibrium.

- At point R, the MC curve cuts the MR curve from below, satisfying the conditions for equilibrium.

6. Equilibrium Level of Output:

- Point R is identified as the point of equilibrium, with OQ2 representing the equilibrium level of output.

Short-run Supply Curve of a Firm in a Competitive Market

- In a perfectly competitive industry, the Marginal Cost (MC) curve of a firm also represents its supply curve. This is because the firm sets its supply based on the price, which is equal to both the Marginal Revenue (MR) and the price in a competitive market.

- When the market price is above the Average Variable Cost (AVC), the firm will produce and supply output where the price equals the marginal cost. For prices below the AVC, the firm will not supply any output because it cannot cover its variable costs.

- For example, at a market price of ₹2, if this price is above the AVC, the firm will not shut down and will supply output where MR = MC. As the price increases to ₹ 3,₹ 4, and so on, the firm increases its supply accordingly. The MC curve above the AVC has the same shape as the supply curve because it indicates the minimum price at which the firm is willing to supply each level of output.

Can a Competitive Firm Make Profits?

- Supernormal Profits: Supernormal profits occur when a firm's average revenue exceeds its average total cost. In other words, when a firm's revenue is higher than what it takes to cover all its costs, including a normal profit for the entrepreneur's managerial efforts. To illustrate this, let's consider an example:

Imagine a firm producing 1,000 units of a product at a cost of ₹15,000. The entrepreneur has invested ₹50,000 in the business, and the normal rate of return in the market is 10%. This means the implicit cost of the entrepreneur's capital is ₹5,000 (10% of ₹50,000). Therefore, the total cost of production is ₹20,000 (₹15,000 + ₹5,000). If the firm sells the product at ₹20 per unit, it earns normal profits because its average revenue (AR) equals its average total cost (ATC) (₹20 = ₹20). However, if the firm sells the product at ₹22 per unit, it earns supernormal profits because its AR (₹22) is greater than its ATC (₹20), resulting in a profit of ₹2 per unit.

- Normal Profits: Normal profits occur when a firm covers its average total cost exactly. In this case, the average revenue (AR) is equal to the average total cost (ATC).

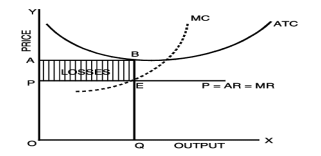

- Losses: Competitive firms can also incur losses in the short run. When a firm's average revenue is less than its average total cost, it experiences losses. For example, if a firm's AR is ₹18 and its ATC is ₹20, the firm is operating at a loss of ₹2 per unit.

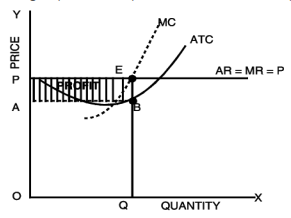

According to the figure, the point E indicates the equilibrium where MR = MC. The equilibrium output is determined to be OQ. At this output level, the price or average revenue (AR) covers the total cost (ATC). Since AR equals ATC, or OP equals EQ, the firm is only making normal profits. By applying the formula TR – TC, it is evident that TR – TC equals zero, indicating no economic profit.

Fig. 20: Short-run equilibrium of a competitive firm: Losses

In the figure, point E represents the equilibrium where AR equals EQ and ATC equals BQ. Since BQ is greater than EQ, the firm is experiencing a per-unit loss of BE, leading to a total loss represented by the area ABEP.

ILLUSTRATION 2

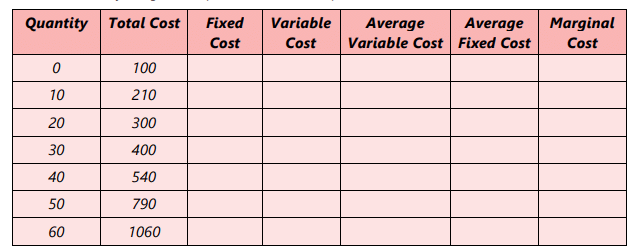

“Tasty Burgers” is a small kiosk selling burgers and is a price-taker. The table below provides the data of 'Tasty Burgers’ output and costs in Rupees.

Q1. If burgers sell for ₹ 14 each, what is Tasty Burgers’ profit-maximizing level of output?

Q2. What is the total variable cost when 60 burgers are produced?

Q3. What is the average fixed cost when 20 burgers are produced?

Q4. Between 10 to 20 burgers, what is the marginal cost?SOLUTION

Answer 1: The price of a burger is ₹ 14. Since "Tasty Burger" is a price-taker, it operates as a perfectly competitive firm. In such a market, all products are sold at the same price, meaning Average Revenue (AR) equals Marginal Revenue (MR). To determine the profit-maximizing level of output, MR must equal Marginal Cost (MC). Here, AR = MR = ₹ 14. From the table, we see that MR (₹ 14) equals MC (₹ 14) when 40 burgers are produced. Therefore, the profit-maximizing level of burger output is 40 units.

Answer 2: The Total Variable Cost (TVC) at 60 burgers is ₹ 960.

Answer 3: The Average Fixed Cost (AFC) at 20 burgers is ₹ 5.

Answer 4: Between 10 to 20 burgers, the Marginal Cost (MC) is ₹ 9.

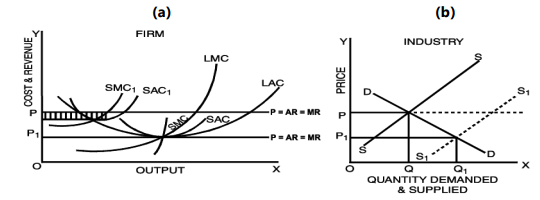

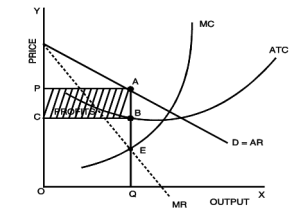

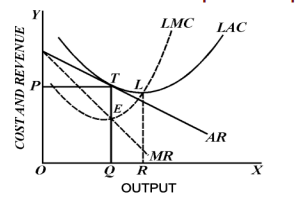

Long-Run Equilibrium of a Competitive Firm

- In the short run, at least one of the firm's inputs is fixed. However, in the long run, firms have the flexibility to adjust the scale of their operations, exit the industry, or new firms can enter the industry. A firm enters a market when it anticipates the possibility of earning a positive long-run profit and exits when it foresees a long-run loss. Firms achieve long-run equilibrium when they have optimized their production scale to operate at the minimum point of their long-run Average Total Cost (ATC) curve, which is tangent to the demand curve determined by the market price.

- In the long run, firms typically earn only normal profits, which are factored into the ATC. If firms are experiencing supernormal profits in the short run, it attracts new entrants into the industry. This influx of new firms leads to a decrease in price (a downward shift in individual demand curves) and an upward shift in cost curves due to rising factor prices as the industry expands. This process continues until the ATC is tangent to the demand curve. Conversely, if firms incur losses in the short run, they exit the industry in the long run. This exit raises prices, and costs may decrease as the industry contracts, until the remaining firms cover their total costs, including a normal profit margin.

- In the long-run equilibrium, firms adjust to a position where they produce at the lowest point of their long-run Average Cost (AC) curve, which is aligned with the market price. If the market price is above the minimum AC, firms make supernormal profits and have the incentive to expand their capacity. This attracts new firms into the industry, increasing market supply and driving down prices until they reach the long-run equilibrium level. Conversely, if firms are making losses, the industry contracts, prices rise, and remaining firms can cover their costs.

- In a perfectly competitive market, the long-run equilibrium condition for a firm is when the marginal cost (MC) is equal to the price (P) and the long-run average cost (LAC). This can be expressed as:

LMC = LAC = P

At this point, the firm adjusts its production capacity to ensure that it produces at the minimum level of LAC. In the long run, the following equalities hold:

SMC = LMC = SAC = LAC = P = MR - This means that at the minimum point of the LAC, the short-run plant is operating at its optimal capacity, causing the minima of the LAC and short-run average cost (SAC) to coincide. - The LMC intersects the LAC at its minimum point, while the SMC intersects the SAC at its minimum point. - Therefore, at the minimum point of the LAC, these conditions are satisfied, ensuring that the firm operates efficiently in the long run.

Long Run Equilibrium of the Industry

Long-run competitive equilibrium in a perfectly competitive industry is achieved when the following three conditions are met:

- All firms are maximizing profit: Every firm in the industry is in equilibrium, ensuring that they are all maximizing their profits.

- Zero economic profit: No firm has an incentive to enter or exit the industry because all firms are earning zero economic profit, also known as normal profit.

- Market equilibrium: The price of the product is set such that the quantity supplied by the industry equals the quantity demanded by consumers.

In the long run, at point E1, Average Revenue (AR) = Marginal Revenue (MR) = Long-Run Average Cost (LAC) = Long-Run Marginal Cost (LMC).

- Each firm in the long run achieves the plant size and output level that minimizes its cost per unit. E1 represents the minimum point of the LAC curve, where the firm produces equilibrium output OM at the lowest (optimal) cost.

- A firm operating at this optimal cost is referred to as an optimal firm. In the long run, all firms under perfect competition become optimal firms with ideal sizes, charging the minimum possible price that covers their marginal cost.

This leads to an optimal allocation of resources, evidenced by the following outcomes:

- Minimum feasible cost: Output is produced at the lowest possible cost.

- Price equals marginal cost: Consumers pay a price that covers the marginal cost, i.e., MC = AR (P = MC).

- Full capacity utilization: Plants operate at full capacity in the long run, eliminating resource wastage, i.e., MC = AC.

- Normal profits: Firms earn only normal profits, i.e., AC = AR.

- Profit maximization: Firms maximize profits (i.e., MC = MR ), but the level of profits remains normal.

- Optimal number of firms: There is an optimal number of firms in the industry.

In summary, in the long run, LAR = LMR = P = LMC = LAC, ensuring an optimal allocation of resources.

However, it is important to note that the perfectly competitive market system is more of a theoretical concept than a reality, as the assumptions underlying this system are rarely found in real-world market conditions.

Monopoly

The term "Monopoly" refers to the concept of being "alone to sell." It describes a situation where there is a single seller offering a product that has no close substitutes. While pure monopoly is rarely encountered in practice, we often observe monopolistic market structures in public utilities such as transportation, water supply, and electricity services.

Features of Monopoly Market

A monopoly market has several distinct features:

(1) Single Seller: In a monopoly, there is only one firm producing or supplying a product. This single firm represents the entire industry, as there is no competition. Monopoly is defined by the lack of competing sellers.

(2) Barriers to Entry: Monopolistic markets have strong barriers to entry, which can be economic, institutional, legal, or artificial. These barriers prevent other firms from entering the market and competing with the monopolist.

(3) No Close Substitutes:. monopolist controls the market supply of a product or service that has no close substitutes. This means the monopolist sets prices rather than taking them from the market. The demand for a monopolist's product is inelastic, meaning that changes in price do not significantly affect the quantity demanded. The demand curve for a monopolist is steeply downward sloping.

(4) Market Power:. monopoly has the power to set prices above marginal cost and earn positive profits. While all goods are substitutes to some extent, a monopolist can exclude competition and control the supply of a good, making them the sole seller in the market.

Let's explore the different reasons why monopolies occur and continue to exist in certain industries.

Causes of Monopoly

1. Barriers to Entry

- The primary reason for the existence of a monopoly is the presence of barriers to entry. These barriers prevent other firms from entering the market and competing with the monopolistic firm.

2. Strategic Control over Resources

- A monopoly can arise when a single firm gains strategic control over a scarce resource, input, or technology. This control limits access for other firms, making it difficult for them to compete.

3. Unique Product Control

- Developing or acquiring control over a unique product that is difficult or costly for other companies to replicate can lead to a monopoly. This uniqueness gives the firm a competitive edge.

4. Government Grants

- Governments can create monopolies by granting exclusive rights to produce and sell a particular good or service. This legal protection eliminates competition.

5. Intellectual Property Protection

- Patents and copyrights awarded by the government protect intellectual property rights and encourage innovation. These legal protections can lead to monopolies by giving firms exclusive control over their inventions.

6. Business Combinations or Cartels

- In some cases, former competitors may illegally cooperate on pricing or market share, forming a cartel. This collaboration can create a monopoly in the market.

7. High Start-Up Costs and Technical Know-How

- Extremely high start-up costs and the need for sophisticated technical expertise can deter new firms from entering the market. This lack of competition can lead to a monopoly.

8. Natural Monopoly

- A natural monopoly occurs when a single firm can produce the entire industry’s output at a lower unit cost than multiple firms. This situation often arises in industries with high infrastructure costs, such as telephone services, natural gas supply, and electrical power distribution.

9. Goodwill and Reputation

- Enormous goodwill and a strong reputation enjoyed by a firm over a long period can create significant barriers to entry for potential competitors.

10. Legal and Regulatory RequirementsStringent legal and regulatory requirements can effectively discourage new firms from entering the market, even if they are not explicitly prohibited.11. Anti-Competitive Practices

- Firms may engage in anti-competitive practices, such as limit pricing or predatory pricing, to eliminate existing or potential competition. These predatory tactics can sustain a monopoly.

While pure monopolies are rare in practice because they are often regulated or prohibited, one producer may dominate the supply of a good or group of goods. Historically, monopolistic markets existed in public utilities such as transport, water, and electricity generation to benefit from large-scale production. However, these markets have been deregulated and opened to competition over time. In India, for example, Indian Railways holds a monopoly in rail transportation, and the government has a monopoly over the production of nuclear power.

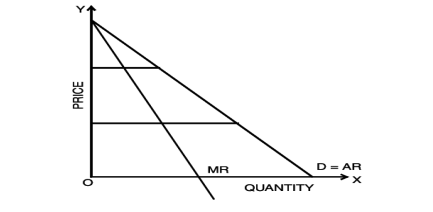

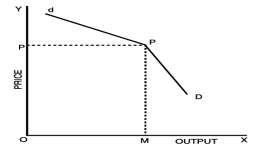

Revenue Curves of a Monopolist

Monopoly and Price Setting

- A monopolist, without government intervention, can set any price and typically chooses the price that maximizes profit.

- Since the monopolist is the sole producer of a product, its demand curve is the same as the market demand curve for that product.

- The market demand curve shows the total quantity buyers are willing to purchase at each price, which also indicates the quantity the monopolist can sell at different prices.

Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue Curves

- When a monopolist sets a single price for all buyers, we can determine its average revenue (AR) and marginal revenue (MR) curves.

- In a monopoly, AR is equal to price since the firm charges the same price for all units sold.

- However, unlike perfect competition where AR and MR are the same, in a monopoly, MR is lower than AR because the monopolist must lower the price to sell additional units.

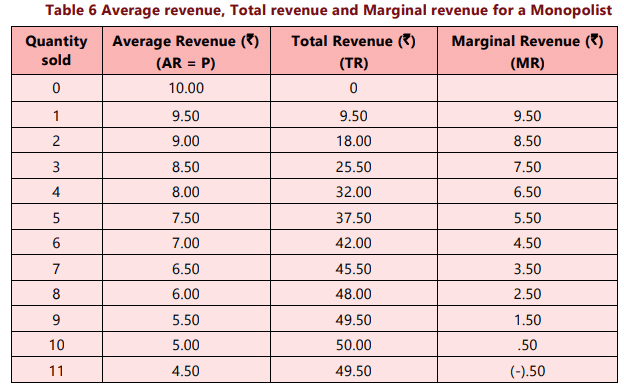

Example of a Monopolist

- Consider a hypothetical scenario where a firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve. For instance, if the firm wants to sell 3 units, it might need to lower the price from ₹9 to ₹8.50.

- This means the third unit is sold for ₹8.50, contributing ₹8.50 to the revenue. However, since the price for the first two units also drops to ₹8.50, the firm receives ₹0.50 less for each of those units.

- As a result, the marginal revenue for selling the third unit is only ₹7.50.

- Similarly, if the firm wants to sell 4 units, it may need to reduce the price from ₹8.50 to ₹8, resulting in a marginal revenue of ₹6.50 for the fourth unit.

Relationship between AR and MR in Monopoly

- In a monopoly, the relationship between average revenue (AR) and marginal revenue (MR) is such that MR is always less than AR.

- This is because to sell additional units, the monopolist has to lower the price not just for the additional unit but for all units sold, leading to a decrease in MR.

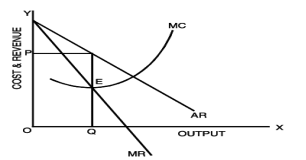

Price and Output Determination in a Simple Monopoly

Introduction

- In a simple monopoly, a single seller dominates the market and sets the price for a product or service. The monopolist faces a downward-sloping demand curve, meaning that as the price decreases, the quantity demanded increases.

- The monopolist aims to maximize profit by determining the optimal price and output level.

Price and Output Determination

- The monopolist will continue to produce and sell the product as long as the marginal cost of production is less than or equal to the marginal revenue generated from selling the additional unit.

- The point at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue (MC = MR) is where the monopolist decides the quantity to produce.

- Once the optimal quantity is determined, the monopolist can then set the price based on the demand curve.

Example: Indian Railways

- Simple Monopoly: Indian Railways charging the same fare from all AC 3-Tier passengers is an example of a simple monopoly. Here, the Railways sets a uniform price for all passengers in this category.

- Discriminating Monopoly: In contrast, when Indian Railways charges different prices for different passengers on the same train, it exemplifies a discriminating monopoly. This dynamic pricing strategy varies based on factors such as demand and booking time.

Key Differences between AR and MR

- AR and MR Curves: Both Average Revenue (AR) and Marginal Revenue (MR) curves are downward sloping. However, the MR curve is steeper, sloping downwards at twice the rate of the AR curve.

- Position of MR Curve: The MR curve is positioned halfway between the AR curve and the Y-axis. This means it divides the horizontal distance between the Y-axis and the AR curve into two equal parts.

- Values of AR and MR: AR can never be zero, as it represents the average revenue per unit sold. On the other hand, MR can be zero or even negative, as it reflects the additional revenue gained from selling one more unit, which can decrease under certain conditions.

Conclusion:

Understanding the dynamics of price and output determination in a simple monopoly is crucial for analyzing how monopolists operate and set prices in the market.

Profit Maximization in a Monopolized Market: Equilibrium of the Monopoly Firm

Monopoly vs. Perfect Competition

- In a perfectly competitive market, firms are price-takers and focus solely on determining output.

- However, a monopolist must decide both the output and the price of their product.

- Both monopolists and firms in perfect competition aim for profit maximization, but their revenue conditions differ.

- A monopolist faces a downward-sloping demand curve, meaning that raising the price will decrease sales, while lowering the price will increase sales.

- The equilibrium of a monopoly firm represents the equilibrium of the entire industry since the firm and industry are identical in this setting.

- We will explore how a monopoly firm determines its output and price in both the short run and long run.

Short Run Equilibrium

Conditions for Equilibrium

- The conditions for equilibrium in a monopoly market are the same as those in a competitive industry.

- A monopoly firm can achieve equilibrium by ensuring that marginal cost (MC) is equal to marginal revenue (MR).

- When MC and MR are equal, the firm can determine the profit-maximizing level of output and price.

Short Run Equilibrium: Losses

- In the short run, a monopolist may face losses. The equilibrium point, where Marginal Cost (MC) intersects Marginal Revenue (MR), is known as point E.

- At this point, the monopolist produces an output level of OQ and sells it at a price of OP.

- The Average Total Cost (SATC) for producing OQ is represented by QA.

- Since QA (cost per unit) is greater than BQ (revenue per unit), the monopolist incurs a loss of AB per unit, totaling ABPC.

- Whether the monopolist continues in the short run depends on covering the Average Variable Cost (AVC). If he can cover AVC and part of fixed costs, he will not shut down, as he contributes to fixed costs already incurred. However, if he cannot cover AVC, he will shut down.

Long Run Equilibrium

- The long run is a period sufficient for the monopolist to adjust plant size or operate the existing plant at any level that maximizes profit.

- Without competition, the monopolist need not produce at the optimal level or reach the minimum of the Long-Run Average Cost (LAC) curve.

- He can produce at a sub-optimal scale where profits are maximized.

- However, the monopolist will not continue if making losses in the long run. He will continue to make supernormal profits as the entry of outside firms is blocked.

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination occurs when a producer sells the same commodity or service to different buyers at different prices for reasons not related to differences in cost. It is a pricing strategy used by monopolists to earn abnormal profits by charging different prices for different units of the same commodity.

Examples of Price Discrimination

- Family doctors charging different fees to rich and poor patients for the same service.

- Electricity companies selling electricity at lower rates for home consumption in rural areas compared to industrial use.

- Railways separating high-value commodities that can bear higher freight charges from other goods.

- Countries dumping goods at low prices in foreign markets to capture them.

- Universities charging higher tuition fees from evening class students than from other scholars.

- Journals charging lower subscription fees from student readers.

- Telecommunication companies charging lower rates for phone calls during off-peak times.

Conditions for Price Discrimination

- Control over Supply: The seller must have some control over the supply of the product and price-setting power. Monopoly power is necessary to discriminate prices.

- Market Segmentation: The seller should be able to divide the market into two or more sub-markets.

- Different Price Elasticity: The price elasticity of the product should differ in various sub-markets. The monopolist sets a high price for buyers with low price elasticity of demand, meaning they do not significantly reduce their purchases in response to a price increase.

- No Market Arbitrage: There should be no possibility for buyers in the low-priced market to resell the product to buyers in the high-priced market.

Price Discrimination and Competition

- Price discrimination cannot occur under perfect competition because sellers have no control over the market-determined price.

- Price discrimination requires an element of monopoly where the seller can influence the price of their product.

Price Discrimination by a Monopolist

- A discriminating monopolist charges higher prices in markets with relatively inelastic demand and lower prices in markets with elastic demand.

- This allows the monopolist to benefit from price discrimination by maximizing profits across different markets.

Numerical Example of Price Discrimination

- Single Monopoly Price:. 30

- Elasticities of Demand: Market A: 2 (inelastic) Market B: 5 (elastic)

- Marginal Revenue (MR) Calculation: Market A: MR = ₹ 30 × (1 - (1/2)). ₹ 15 Market B: MR = ₹ 30 × (1 - (1/5)). ₹ 24

- Profitability of Transfer: Transferring one unit from Market A to Market B increases revenue by ₹ 9 (from ₹ 15 to ₹ 24).

- Price Adjustment: As units are transferred, price in Market A rises and price in Market B falls, reflecting price discrimination.

- Equilibrium Point: There is a limit to how much output can be transferred. The process continues until MR in both markets becomes equal.

- Different Pricing: Once the equilibrium point is reached, the monopolist charges different prices: a higher price in Market A (lower elasticity) and a lower price in Market B (higher elasticity).

Objectives of Price Discrimination

- To earn maximum profit

- To dispose of surplus stock

- To enjoy economies of scale

- To capture foreign markets

- To secure equity through pricing

Reasons for Price Discrimination

- Differences in the nature and types of customers purchasing the products

- Differences in the locality where the products are sold

- Differences in income levels, age, size of the purchase, and time of purchase

Price Discrimination: Types and Equilibrium

Price discrimination is closely linked to the consumer surplus that consumers experience. Professor Pigou identified three degrees of price discrimination:

(i) First Degree Price Discrimination:

- In this form, the monopolist targets individual consumers and charges them the maximum price they are willing and able to pay, thereby capturing the entire consumer surplus.

- Examples include professionals like doctors, lawyers, and consultants charging varying fees, as well as pricing determined through bidding, auctions, and negotiations.

(ii) Second Degree Price Discrimination:

- Different prices are charged based on the quantity purchased, allowing the monopolist to capture a portion of the consumer surplus.

- This can occur in two ways:

- a) Different prices for different quantities, such as family packs of soap or biscuits costing less per kilogram than smaller packs.

- b) Varying prices for consecutive purchases, as seen in services like telephone, electricity, and water, where prices may increase after a certain consumption threshold.

(iii) Third Degree Price Discrimination:

- Prices vary based on attributes like location or customer segment.

- The monopolist divides consumers into distinct sub-markets and charges different prices in each.

- Examples include dumping, varying prices for domestic and commercial use, and reduced railway fares for senior citizens.

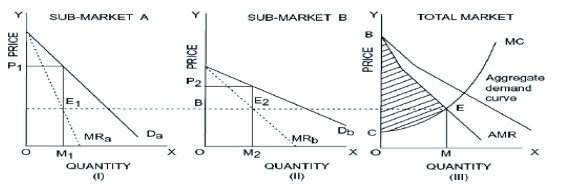

Equilibrium under Price Discrimination

- In simple monopoly, a single price is set for the entire output. In contrast, price discrimination involves charging different prices in various sub-markets.

- The monopolist first divides the total market into sub-markets based on differences in demand elasticity.

- For illustrative purposes, consider a scenario with two sub-markets.

- To achieve equilibrium, the discriminating monopolist must make three key decisions:

- a) Determine the total output to produce.

- b) Decide how to allocate the total output between the two sub-markets.

- c) Set the prices for each sub-market.

- The decision on total output is guided by the same marginal principle as in perfect competition or simple monopoly.

- The discriminating monopolist compares the aggregate marginal revenue of the two sub-markets with the marginal cost of total output.

- The aggregate marginal revenue curve is derived by summing the marginal revenue curves of the sub-markets laterally.

Discriminating Monopoly: Profit Maximization and Output Distribution

In a discriminating monopoly, the monopolist aims to maximize profits by determining the optimal level of output and then distributing that output between different sub-markets. Here’s how the process works:

1. Determining Total Output

- The monopolist looks at the aggregate marginal revenue (AMR) from both sub-markets and the marginal cost (MC) of production.

- Profits are maximized when AMR equals MC. This point determines the total output (OM) that the monopolist will produce.

2. Distributing Output Between Sub-Markets

- Once the total output (OM) is set, the monopolist needs to divide this output between sub-market A and sub-market B.

- The goal is to distribute the output in such a way that marginal revenues (MR) in both sub-markets are equal. This is crucial for maximizing profits.

3. Ensuring Equilibrium

- For the monopolist to be in equilibrium, the following conditions must be met:

- MR in sub-market A. MR in sub-market B. MC of the whole output (ME)

- This ensures that the total output (OM) is sold across both sub-markets without any excess or shortage.

4. Example of Output Distribution

- Suppose the total output (OM) is 100 units.

- If MR in sub-market A is higher than MR in sub-market B,

- the monopolist will allocate more units to sub-market A until MR in both markets is equal.

Price Discrimination by a Monopolist

Total Output and Price Determination

- A discriminating monopolist will produce a total output of OM and sell OM1 in sub-market A and OM2 in sub-market B.

- In sub-market A, the price OP1 will be set for OM1, while in sub-market B, the price OP2 will be set for OM2.

- Price OP1 will be higher than price OP2 because the demand in sub-market A is less elastic compared to sub-market B.

Purpose of Price Discrimination

- Price discrimination is used by monopolists to achieve higher profits and maintain monopoly power.

- While it leads to a loss of economic welfare due to higher prices than marginal costs and reduces consumer surplus, there are also positive outcomes.

- The increased revenue from price discrimination can help some firms remain profitable.

- Peak load pricing allows firms with capacity constraints to spread demand to off-peak times, improving capacity utilization and reducing production costs.

- Essential services like railways may not be viable without price discrimination.

- Some consumers, particularly low-income individuals, may benefit from lower prices that would not be possible with uniform high pricing.

Economic Effects of Monopoly

Monopoly is often criticized for diminishing overall economic welfare due to a decline in both productive and allocative efficiency.

- Price and Output: Monopolists set prices significantly higher and produce lower quantities compared to what would occur in a competitive market.

- Economic Profits: Monopolists sustain long-term economic profits that are generally considered unjustifiable.

- Consumer Surplus: Monopoly prices are above marginal costs, leading to a reduction in consumer surplus. This results in a transfer of income from consumers to monopolists. Consumers not only face higher prices but also lack alternative, more reasonably priced options.

- Consumer Sovereignty: Monopoly restricts consumer sovereignty, limiting consumers’ ability to choose products according to their preferences.

- Barriers to Entry: Monopolists may employ unfair tactics to create barriers to entry, thereby maintaining their monopoly power. They often invest substantial resources to uphold their monopoly position, which increases the average total cost of production.

- Political Influence: Monopolists with significant financial resources are in a strong position to influence the political landscape, potentially securing favorable legislation.

- Innovation: Monopolists often lack the incentive to introduce efficient innovations that enhance product quality and reduce production costs.

- Supplier Power: Monopolies can leverage their power to negotiate lower prices with suppliers.

- X Inefficiency: The economy may experience ‘X’ inefficiency, which refers to the loss of management efficiency in markets with limited or absent competition.

- Government Regulation: Due to the exploitative nature and adverse outcomes associated with monopolies, governments implement measures to prevent the formation of monopolies and regulate existing ones.

Characteristics of Monopolistic Competition

The market for soaps and detergents, featuring brands like Lux, Vivel, Cinthol, Dettol, Liril, Pears, Lifebuoy Plus, and Dove, illustrates the concept of monopolistic competition. While these soaps are similar in many ways, each brand differentiates itself through unique positioning. For example:

- Lux: Marketed as a beauty soap.

- Liril: Associated with freshness.

- Dettol: Positioned as an antiseptic soap.

- Dove: Promoted for ensuring young, smooth skin.

This differentiation allows each seller to attract customers based on factors other than price, exemplifying the monopolistic aspect of the market.

Prevalence of Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competition is more common than pure competition or pure monopoly. Industries characterized by monopolistic competition include:

- Clothing: Various brands and styles cater to different consumer preferences.

- Manufacturing: Companies produce similar yet differentiated products.

- Retail Trade: Unique stores offer distinct shopping experiences in large cities.

Examples in Urban Areas

In medium-sized or large cities, numerous businesses operate under monopolistic competition, including:

- Grocery shops

- Shoe stores

- Stationery shops

- Restaurants

- Repair shops

- Laundries

- Manufacturers of women’s dresses

- Beauty parlours

Features of Monopolistic Competition

- Large Number of Sellers: In a monopolistically competitive market, there are many independent firms, each holding a small share of the market.

- Product Differentiation: Products from different sellers are distinguished by factors such as brand, size, design, color, shape, performance, features, and packaging. This differentiation can be genuine or perceived. Strong branding leads to customer loyalty, allowing producers to raise prices without losing all customers. However, since brands are close substitutes, price increases will result in some loss of customers to competitors. This market is a mix of monopoly and perfect competition.

- Freedom of Entry and Exit: Barriers to entry are low, allowing new firms to enter the market when they see profit potential, and existing firms can exit freely.

- Non-Price Competition: Firms compete on factors other than price, such as aggressive advertising, product development, improved distribution, and better after-sales service. Non-price competition is often based on product differentiation, as price competition can lead to price wars that harm profit margins.

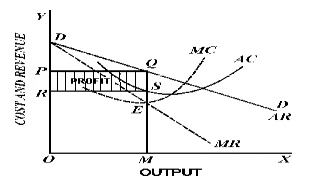

Price and Output Determination in Monopolistic Competition: Firm Equilibrium

In a monopolistically competitive market, where products are differentiated, each firm faces a downward-sloping demand curve rather than a perfectly elastic one. This is because each firm has some degree of market power to set its own price. The elasticity of this demand curve varies with the degree of differentiation; the less differentiated the product, the more elastic the demand curve.

Short-Run Equilibrium with Supernormal Profits

In the short run, a firm in a monopolistically competitive market can achieve supernormal profits under certain conditions:

- MC Curve and MR Curve: For equilibrium, the Marginal Cost (MC) curve must intersect the Marginal Revenue (MR) curve from below.

- Equilibrium Point: At point E, where MC cuts the MR curve, the equilibrium price is OP and the equilibrium output is OM.

- Supernormal Profit: The per-unit cost is SM, and the per-unit supernormal profit (price - cost) is QS (or PR). The total supernormal profit is PQSR.

Short-Run Equilibrium with LossesIt is also possible for a firm in monopolistic competition to incur losses in the short run, as depicted in certain scenarios. In such cases:

- Per Unit Cost: The per unit cost (HN) is higher than the price (OT or KN) of the product.

- Loss Per Unit: The loss per unit is calculated as KH (HN-KN).

- Total Loss: The total loss is represented as GHKT.

Long-Run Equilibrium of the Firm

In the long run, all firms in a monopolistically competitive industry will earn only normal profits. This is because:

- Entry of New Firms: If firms are making supernormal profits in the short run, new firms will be attracted to enter the industry.

- Decrease in Profits: As more firms enter the market, the total demand for the product gets divided among a larger number of firms, leading to a decrease in profits per firm.

- Normal Profits: This process continues until all supernormal profits are eliminated, and all firms are left with only normal profits.

Long-Run Equilibrium: Zero Economic Profits

In the long-run equilibrium of a firm in monopolistic competition:

- Average Revenue and Average Cost: The average revenue curve intersects the average cost curve at a point (e.g., point T), indicating that the firm is covering its costs but not making any economic profits.

- Equilibrium Condition: At equilibrium, where MC equals MR, the firm earns zero supernormal profits because average revenue equals average costs.

- Normal Profits: All firms in the market are earning zero economic profits, which means they are making just normal profits.

When firms consistently incur losses over time, they will eventually leave the market. This process continues until only those firms capable of making normal profits remain. It is important to understand that a firm in long-run equilibrium does not operate at its full potential for economies of scale. In simpler terms, these firms are not utilizing their production capacity to the fullest. Attempting to produce more to achieve lower costs would be unwise because the price reduction from selling a larger output would outweigh the cost savings. For instance, if a firm increases its output to a certain point, it may find that its average total cost exceeds its average revenue. This situation indicates that a firm in monopolistic competition, when in long-run equilibrium, experiences excess capacity, meaning it produces less than its maximum capacity. The firm could increase its output to reduce average costs, but it refrains from doing so because the decrease in average revenue would be greater than the decrease in average costs. This scenario illustrates that firms in monopolistic competition are not operating at their optimal size and that each firm has excess production capacity.

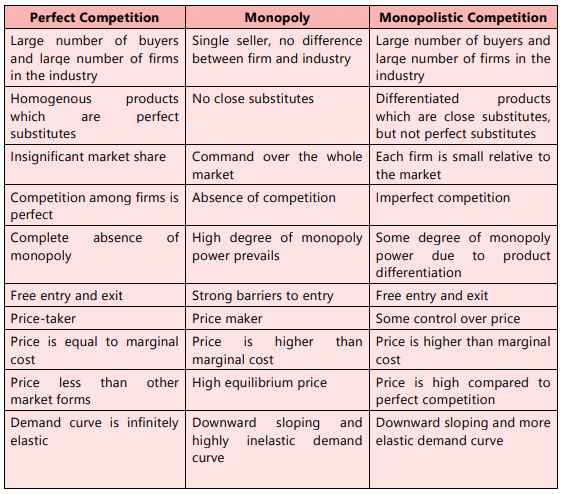

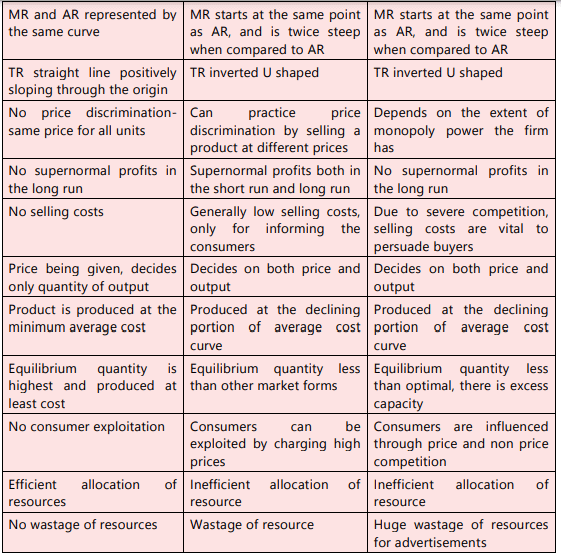

The table below compares Perfect Competition, Monopoly, and Monopolistic Competition.

Oligopoly

Oligopoly is a market form where a few firms dominate the market, either selling identical or similar products. This situation arises when factors that lead to monopolies are present but with multiple firms instead of one. Unlike a monopoly where a single firm has complete control, in an oligopoly, a small number of firms have the power to influence the market and prevent new competitors from entering.In India, industries such as cold drinks, automobiles, airlines, petroleum refining, power generation, mobile telephony, and internet service providers are examples of oligopolistic markets. These industries are characterized by a limited number of firms that control a significant portion of the market.

Game Theory in Oligopoly

- Game Theory offers a unique perspective on how oligopolistic firms behave strategically in uncertain situations. Developed by Von Neumann and Oskar Morgentern in 1944, Game Theory explores rational behavior in conflict scenarios such as military, political, and business rivalries.

- In the context of oligopoly, firms must choose their strategies while anticipating how their competitors will react to their actions. This involves a level of uncertainty, as firms need to predict the responses of their rivals to remain competitive.

Different Types of Oligopoly

- Pure Oligopoly or Perfect Oligopoly. This type of oligopoly occurs when the products offered by firms are identical or homogeneous. For example, in the aluminium industry, companies produce the same type of product without significant differentiation. Pure oligopolies often involve industries that process raw materials or produce intermediate goods used as inputs by other sectors. Notable examples include the petroleum, steel, and aluminium industries.

- Differentiated or Imperfect Oligopoly. In this type, the goods sold by firms are differentiated based on certain characteristics or features. For instance, in the market for talcum powder, different brands offer products with varying scents, ingredients, or packaging, leading to differentiation even though the basic product is similar.

- Open Oligopoly. An open oligopoly allows new firms to enter the market and compete with existing players. There are no significant barriers to entry, enabling potential competitors to join the market relatively easily.

- Closed Oligopoly. In a closed oligopoly, entry into the market is restricted, and new firms cannot easily compete with the existing ones. Barriers to entry may include high startup costs, regulatory restrictions, or other factors that prevent new competitors from entering the market.

- Collusive Oligopoly. This type occurs when a few firms within the oligopoly reach a common understanding or agreement to act together, either in setting prices, determining output levels, or both. Collusion can lead to higher prices and reduced competition among the participating firms.

- Competitive Oligopoly. In contrast to collusive oligopoly, competitive oligopoly refers to a situation where firms within the oligopoly do not have a common understanding and compete against each other. Each firm independently sets its prices and output levels, leading to competition within the market.

- Partial Oligopoly. Oligopoly is considered partial when the industry is dominated by one large firm that acts as a leader or price setter for the group. The dominating firm influences pricing and may set the standard for other firms in the industry.

- Full Oligopoly. In a full oligopoly, there is no single price leader, and the market is characterized by the absence of price leadership. Firms within the oligopoly may compete more actively without a dominant leader setting prices.

- Syndicated Oligopoly. Syndicated oligopoly occurs when firms sell their products through a centralized syndicate or organization. This syndicate coordinates sales and may set prices or other terms for the participating firms.

- Organized Oligopoly. In an organized oligopoly, firms come together to form a central association that helps in fixing prices, output levels, quotas, and other important aspects of their operations. This organization helps in coordinating activities among the member firms.

Characteristics of Oligopoly Market

Market Control by Few Firms: In an oligopoly, a small number of large firms dominate the industry. These firms are significant in size relative to the overall market, giving them substantial control. While there may be many firms in the market, the majority of the market share is held by a few large companies. These companies establish and maintain market control. There are also strong barriers to entry, similar to those in a monopoly.

- Strategic Interdependence:. key characteristic of oligopoly is the interdependence in decision-making among the few firms in the industry. Since there are only a few sellers, competition among them is intense. Each firm is large enough to impact the market, so they must respond to each other's actions. For example, if one firm changes its price, output, or product, the others will react by adjusting their prices, output, or advertising strategies. Therefore, an oligopolistic firm must consider not only the demand for its product but also how its rivals will respond to any significant decision. Ignoring or misjudging competitors' behavior can lead to a decline in profits.

- Importance of Advertising and Selling Costs: Due to the interdependence among oligopolists, firms need to use various aggressive and defensive marketing strategies to gain or maintain market share. This requires significant spending on advertising and sales promotion. In an oligopoly, firms focus on competing through non-price means rather than price cutting. Engaging in price wars by undercutting each other can drive some firms out of the market, as customers will flock to the lowest-priced seller.

- Group Behaviour: The theory of oligopoly is based on group behaviour rather than individual or mass behaviour. Profit-maximizing behaviour by oligopolists may not always be accurate. There is no universally accepted theory of group behaviour in this context. Firms may choose to collaborate as a group to promote their common interests, with or without a leader. If there is a leading firm, it must be able to influence and guide the others. Understanding group behaviour is crucial in the context of oligopoly.

Price and Output Decisions in an Oligopolistic Market

Oligopoly refers to a market structure where a few large firms dominate the market. The behaviour of these firms is interdependent, meaning that each firm must consider the potential reactions of its rivals when making decisions about price and output. The extent of market power and profitability for each firm depends on how competitive or cooperative the other firms are.Strategic Behaviour

- In an oligopoly, firms must act strategically when setting prices and outputs. They need to anticipate how their competitors will respond to changes in price or quantity.

- If rival firms are cooperative and do not compete aggressively, individual firms can exercise more market power and set prices above marginal costs.

Uncertainty in Demand

- An oligopolistic firm cannot rely on a stable demand curve because its rivals’ reactions can shift the demand curve.

- When an oligopolist changes its price, competitors will likely adjust their prices in response, affecting the demand for the original firm’s products.

Price-Output Models for Oligopoly

- Economists have developed various models to understand price and output decisions in oligopoly markets, each based on different assumptions about how firms interact.

- Cournot Model: Firms compete by choosing output levels independently and simultaneously, without colluding.

- Stackelberg Model: One firm (the leader) sets its output first, and other firms (followers) adjust their outputs based on the leader’s decision.

- Bertrand Model: Firms compete by setting prices independently to maximize profits, focusing on price rather than output.

Interdependence and Decision-Making

- In some models, firms are assumed to ignore their interdependence, leading to a more straightforward demand curve. In such cases, equilibrium output is determined by setting marginal cost equal to marginal revenue.

- Other models, like Cournot and Stackelberg, involve firms making decisions based on anticipated reactions from competitors, adding a layer of complexity to their strategic planning.

Collusion among Oligopolists

The third approach involves oligopolists entering into agreements to pursue their common interests. They act together like a monopoly, setting prices to maximize their joint profits. Once they achieve this, they share the profits, market, or output among themselves as per their agreement.

- Collusion and Cartels. Collusion or forming a cartel is typically considered illegal because it restricts trade and creates conditions similar to a monopoly. However, in reality, many cartels operate in the world economy, either formally or tacitly.

- Example - OPEC. The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a prime example of such an agreement among oligopolists. OPEC members collaborate to manage oil production and pricing, illustrating how oligopolists can work together to influence the market.

Price Leadership in Oligopoly

Oligopolistic markets, where a few firms dominate, often face intricate challenges when it comes to price setting. In such scenarios, price leadership becomes a crucial mechanism. Price leadership occurs when one firm, often the dominant or low-cost firm, sets the price for the entire market, and other firms follow suit. This can happen in different forms:- Price Leadership by Dominant Firm: In cases where a large firm is surrounded by smaller fringe firms, the dominant firm may adopt a "live and let live" approach. This involves setting a price that maximizes its profit while considering the presence and behavior of the fringe firms. The dominant firm essentially leads the market by setting a price that reflects its market power and profit objectives.

- Price Leadership by Low-Cost Firm: In this scenario, a low-cost firm sets the price in a way that allows for some profit margin for other firms as well. This type of price leadership helps maintain a balance in the market, ensuring that all firms can operate profitably while still competing.

- Barometric Price Leadership: This form of price leadership involves an experienced, large, or respected firm in the industry acting as a price leader. This firm assesses market conditions, including demand, costs, and competition, and adjusts prices accordingly. The changes made by the price leader are generally accepted by other firms in the industry, as they are seen as beneficial for the overall market.

Cartels and Market Power Cartels are typically formed in industries with a few firms of similar size. When a group of firms agrees to coordinate their activities, they create a cartel. Most cartels consist of only a subset of producers. When participating producers adhere to the cartel's agreements, the cartel can exert significant market power and achieve monopoly profits, especially when the product's demand is inelastic.

However, in some cases, there may be a dominant or large firm alongside many smaller firms. If the smaller firms are numerous or unreliable, the large firm must consider their behavior when setting prices. One approach is the "live and let live" philosophy, where the dominant firm acknowledges the presence of fringe firms and sets prices to maximize its profits while considering their actions. This is known as price leadership by the dominant firm.

Conclusion Price setting in oligopoly is a complex task that relies on various assumptions about the behavior of the oligopolistic group. Different forms of price leadership, such as by dominant firms, low-cost firms, or barometric leaders, play a crucial role in how prices are determined in such markets.

Kinked Demand Curve

In oligopolistic industries, prices often remain stable and do not change frequently, even when costs decline. This phenomenon is explained by the kinked demand curve hypothesis proposed by economist Paul A. Sweezy. According to this model, the demand curve faced by an oligopolist has a distinct "kink" at the current price level, leading to price rigidity in such markets.

Understanding the Kinked Demand Curve

- The kinked demand curve suggests that the demand curve for an oligopolistic firm has a "kink" or bend at the prevailing price level, which is characterized by two segments with different elasticities.

- Above the prevailing price level (the upper segment), the demand curve is elastic. This means that a small increase in price would lead to a large decrease in quantity demanded.

- Below the prevailing price level (the lower segment), the demand curve is inelastic. This indicates that a decrease in price would result in a small increase in quantity demanded.

Competitive Reaction Pattern

- The kinked demand curve is based on the assumption of a specific competitive reaction pattern among oligopolists:

- Price Decrease: If an oligopolist lowers its price, it expects that its competitors will follow suit and also reduce their prices. This is because each firm wants to retain its customers, and a price cut would lead to a loss of customers to the firm that lowers its price first.

- Price Increase: Conversely, if an oligopolist raises its price, it anticipates that its competitors will not follow this price increase. As a result, the firm that raises its price would lose customers to its competitors, who would attract these customers with lower prices.

Implications of the Kinked Demand Curve

- The kinked demand curve illustrates why prices in oligopolistic markets tend to be rigid and why firms are reluctant to change prices.

- Price Cuts: When an oligopolist considers a price cut, the demand curve above the prevailing price level is elastic. This means that the firm must be cautious, as a price cut may not lead to a proportional increase in sales due to the subsequent price cuts by competitors.

- Price Increases: On the other hand, if a firm contemplates a price increase, the demand curve below the prevailing price level is inelastic. This indicates that a price increase could result in a significant loss of sales, as customers would switch to competitors offering lower prices.

Conclusion

- The kinked demand curve hypothesis helps explain the price rigidity observed in oligopolistic industries. It highlights the strategic interdependence among firms in such markets, where the actions of one firm significantly impact the decisions of others. By understanding this model, we can better comprehend the pricing behavior and dynamics within oligopolistic industries.

- In an oligopoly, the way one firm sets its price is closely linked to how its competitors will react. If a firm lowers its price, its rivals are likely to follow suit and cut their prices as well. On the other hand, if a firm raises its price, the impact on its sales depends on whether its competitors also raise their prices.

- Firms in an oligopoly tend to stick to the prevailing price because they see no advantage in changing it. This creates a "kink" in the demand curve at the current price level. The kinked demand curve theory explains why prices in oligopolistic markets are often rigid or sticky.

- Oligopolistic firms have a strong preference for price stability. Even when costs or demand change, these firms are reluctant to alter the price they have set. This is because they are uncertain about how their rivals will respond to a price change, and they prefer to avoid the risks associated with fluctuating prices.

Other Important Market Forms

- Duopoly. A specific type of oligopoly where the market is dominated by just two firms.

- Monopsony. This market form features a single buyer for a product or service, typically seen in factor markets where one firm is the sole purchaser of a factor.

- Oligopsony. In this market, a small number of large buyers dominate, which is most relevant in factor markets.

- Bilateral Monopoly. This market structure involves a single buyer and a single seller, effectively combining elements of both monopoly and monopsony markets.

|

86 videos|255 docs|58 tests

|

FAQs on Unit 3: Price Output Determination under Different Market Forms Chapter Notes - Business Economics for CA Foundation

| 1. What are the key features of a perfectly competitive market? |  |

| 2. How is price determined in a perfectly competitive market? |  |

| 3. What is the short-run supply curve of a firm in a competitive market? |  |

| 4. What are the features of a monopoly market? |  |

| 5. How do monopolies arise in the market? |  |