Unit 1: The Concept of Money Demand: Important Theories Chapter Notes | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Unit Overview |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Demand for Money |

|

| Theories of Demand for Money |

|

| Post-Keynesian Developments in the Theory of Demand for Money |

|

Unit Overview

Introduction

Money is crucial for meeting human needs and keeping things running smoothly. Most people handle money regularly, but not everyone understands its true nature and function.

Definition of Money:

- Money can be defined as anything that serves as a:

- Store of Value: Allows people to save and use it later, helping them manage purchases over time.

- Unit of Account: Provides a common basis for pricing goods and services.

- Medium of Exchange: Facilitates buying and selling between people.

Importance of Money:

- Without money, we would rely on barter, making trade extremely difficult. For instance, a mechanic needing food would have to find a farmer with a broken car, which is often impractical.

- Money simplifies this process by allowing people to sell their goods or services for money, which can then be used to buy what they need from others.

- As specialization increases, production rises, leading to higher demand for transactions and, consequently, more need for money.

Characteristics of Money:

- Money holds its value over time, can be easily converted into prices, and is widely accepted.

- Throughout history, various items have been used as money, including cowry shells, barley, peppercorns, gold, and silver.

Fiat Money:

- Historical Context: Gold and silver were once the primary forms of currency. However, due to their weight, people began depositing these precious metals in banks and using notes as a claim to the metal.

- Transition to Fiat Money: Over time, the paper claims were no longer linked to the actual metal, giving rise to fiat money. This type of currency is considered materially worthless but holds value because a nation collectively agrees to it.

- Trust in Currency: The effectiveness of money relies on the belief that it will retain its value. The evolution of money reflects a shift from individual barter to collective acceptance and, eventually, government authority.

Money is a fundamental concept in economics, but there is no single, universally accepted definition of it. The Reserve Bank of India describes money as a set of liquid financial assets that can influence overall economic activity. In statistical terms, money might also include certain liquid liabilities of specific financial intermediaries.

For money to effectively serve its purposes, it should possess several key characteristics:

Generally Acceptable: Money should be widely accepted as a medium of exchange.

Durable or Long-Lasting: Money should have a long lifespan and not deteriorate quickly.

Effortlessly Recognizable: It should be easy to identify and distinguish money from other items.

Difficult to Counterfeit: Money should be hard to reproduce, preventing fraudulent activities.

Relatively Scarce with Elasticity of Supply: While money should be scarce, its supply should be adjustable to meet demand.

Portable: Money should be easy to carry and transport.

Possessing Uniformity: All units of money should be uniform and identical.

Divisible: Money should be divisible into smaller units without losing value, allowing for transactions of varying sizes.

How Money is Measured

In official statistics, the measurement of money in an economy is typically done through the concept of broad money. Broad money includes all financial assets that provide a store of value and liquidity. Liquidity refers to the ease with which financial assets can be converted into cash or another form of money at short notice, close to their full market value. While currency and transferable deposits (narrow money) are included in broad money by all countries, there are additional components that can also be counted as broad money. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the following items can be considered as part of broad money:

- National Currencies: Typically issued by the central government.

- Transferable Deposits: These include demand deposits (transferable by check or money order), bank checks (used as a medium of exchange), travelers checks (used for transactions with residents), and foreign-currency deposits commonly used for payments.

- Other Deposits: This category includes nontransferable savings deposits, term deposits (funds left on deposit for a fixed period), and repurchase agreements (selling a security with an agreement to buy it back at a fixed price).

- Securities Other Than Shares of Stock: Tradable certificates of deposit and commercial paper (corporate IOUs) fall under this category.

Source: IMF

Demand for Money

Demand for Money refers to the desire to hold money because of its purchasing power. It is a demand for real balances, meaning people want money to have control over real goods and services. Essentially, it is about wanting liquidity and a way to store value. The demand for money is a decision on how much wealth to keep in the form of money instead of other assets like bonds.

Importance of Demand for Money:

- The demand for money plays a crucial role in determining interest rates, prices, and income in an economy.

- Understanding what affects money demand is essential for setting targets by monetary authorities.

Factors Affecting Demand for Money:

- Income: Higher income leads to higher expenditure, and richer people tend to hold more money to finance their spending.

- Price Level: The amount of money people want to hold is directly proportional to the prevailing price level. Higher prices mean a greater need for money.

- Interest Rates: The opportunity cost of holding money is the interest rate that could be earned on other assets. Higher interest rates increase this opportunity cost, leading to a lower demand for money.

- Financial Innovations: Advances such as internet banking, app-based transfers, and ATMs reduce the need for holding liquid money.

Both households and firms hold money for similar basic reasons, primarily for liquidity and the convenience of day-to-day transactions.

Theories of Demand for Money

Classical Approach: The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM)

The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) is a fundamental concept in economics that explores the relationship between the amount of money in circulation and the price level of goods and services. It was first introduced by Irving Fisher in his book "The Purchasing Power of Money" published in 1911. Fisher's version of the QTM, known as the equation of exchange, is expressed as: MV = PT

Where:

- M represents the total amount of money in circulation in an economy.

- V is the transactions velocity of circulation, indicating how often a unit of money is spent on goods and services.

- P denotes the average price level, calculated as P = MV/T.

- T represents the total number of transactions, which later economists replaced with real output (Y).

Fisher later expanded this equation to include demand (bank) deposits and their velocity, leading to the modified equation: MV + M'V' = PT

In this expanded form:

- M' is the total quantity of credit money.

- V' is the velocity of circulation of credit money.

Key Concepts:

- The total supply of money includes both actual money (M) and credit money (M') along with their respective velocities (V and V').

- The velocities of money and credit money are considered constant in the short run.

- The volume of transactions (T) is assumed to be fixed in the short run due to full employment.

Implications:

- The demand for money is represented by the equation PT, which equals the supply of money (MV + M'V').

- The total value of transactions in a given period is reflected by PT, while the money flow is represented by MV + M'V'.

- An increase in the number of transactions leads to a higher demand for money.

The Cambridge Approach to Money Demand

- In the early 1900s, Cambridge Economists Alfred Marshall, A.C. Pigou, D.H. Robertson, and John Maynard Keynes introduced a new perspective on the quantity theory of money known as the cash balance approach.

- This approach differed from earlier views by emphasizing two key ways in which money increases utility:

- Transaction Motive: Money allows for the separation of sale and purchase over time, rather than requiring them to occur simultaneously.

- Precautionary Motive: Money serves as a hedge against uncertainty, acting as a temporary store of wealth.

- The Cambridge approach suggests that individuals need a "temporary abode" of purchasing power to guard against uncertainty since sales and purchases do not happen at the same time. This introduces the idea of precautionary demand for money.

- Money is demanded for itself because it provides utility through its role in storing wealth and serving as a precautionary measure.

- Factors Influencing Money Demand: The demand for money depends on income and other factors such as wealth and interest rates.

- Income: Higher income leads to increased transactions, necessitating more money as a temporary store of value to manage transaction costs.

- Wealth and Interest Rates: These factors also play a significant role in determining the demand for money.

- Cambridge Money Demand Function: The demand for money is expressed as:

- Md = k PY,

Where:

Md = Demand for money balances

Y = Real national income

P = Average price level of currently produced goods and services

PY = Nominal income

k = Cambridge k, a parameter reflecting economic structure and monetary habits - Cambridge k: This parameter represents the ratio of total transactions to income and the ratio of desired money balances to total transactions. It indicates that demand for money (M) equals k proportion of total money income.

- Focus on Money Demand: The neoclassical theory shifted the emphasis of the quantity theory of money to money demand, positing that money demand is solely a function of money income.

- Transaction Demand for Money: Both the neoclassical and Cambridge versions are primarily concerned with money as a means of transactions or exchange, presenting models of transaction demand for money.

The Keynesian Theory of Demand for Money

Introduction

- Keynes' theory of the demand for money is known as 'Liquidity Preference Theory'. Liquidity preference refers to people's desire to hold money instead of securities or long-term investments.

- According to Keynes, people hold money for three reasons: (i) Transactions motive, (ii) Precautionary motive, and (iii) Speculative motive.

(a) The Transactions Motive

- The transactions motive for holding cash relates to the need for cash for current transactions for personal and business exchange.

- The transaction motive is further classified into income motive and business (trade) motive, both of which stressed on the requirement of individuals and businesses respectively to bridge the time gap between receipt of income and planned expenditures.

- Keynes did not consider the transaction balances as being affected by interest rates.

- The transaction demand for money is directly related to the level of income.

- The transactions demand for money is a direct proportional and positive function of the level of income and is stated as follows: Lr = kY

- Lr, is the transactions demand for money, k is the ratio of earnings which is kept for transactions purposes is the earnings.

- Keynes considered the aggregate demand for money for transaction purposes as the sum of individual demand and therefore, the aggregate transaction demand for money is a function of national income.

(b) The Precautionary Motive

- Individuals and businesses keep a portion of their income to finance unforeseen and unpredictable contingencies involving money payments.

- The amount of money demanded under the precautionary motive depends on the size of income, prevailing economic and political conditions, and personal characteristics such as optimism, pessimism, and farsightedness.

- Keynes regarded the precautionary balances as income elastic and not very sensitive to the rate of interest.

(c) The Speculative Demand for Money

- The speculative motive reflects people’s desire to hold cash to exploit attractive investment opportunities requiring cash expenditure.

- According to Keynes, people demand to hold money balances to take advantage of future changes in the rate of interest, which is the same as future changes in bond prices.

- Keynes assumed that the expected return on money is zero, while the expected returns on bonds are of two types.

Speculative Demand for Money

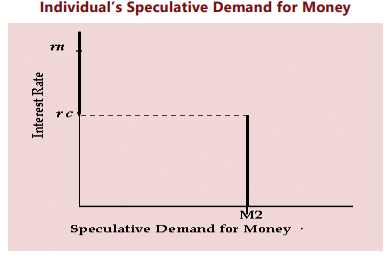

(i) Speculative demand for money refers to the desire to hold cash balances in anticipation of future changes in interest rates and bond prices. It is influenced by the relationship between the current market interest rate and a perceived 'normal' or 'critical' interest rate.

(ii) When the current market interest rate is high relative to the 'normal' rate, investors expect interest rates to fall in the future. This leads to an increase in bond prices. In this scenario, wealth-holders are incentivized to convert their cash balances into bonds because:

(a) They can earn a higher rate of return on bonds.

(b) They anticipate capital gains from rising bond prices due to the expected decline in interest rates.

(iii) Conversely, when the current interest rate is low compared to the 'normal' rate, investors expect interest rates to rise in the future, leading to a decrease in bond prices. In this situation, wealth-holders prefer to keep their wealth in liquid cash rather than bonds because:

(a) The opportunity cost of forgone interest income is small.

(b) They want to avoid potential capital losses from falling bond prices.

(c) The return on cash balances is expected to be greater than the return on alternative assets.

(iv) If interest rates do rise in the future, bond prices will fall, and holding cash balances allows investors to purchase bonds at lower prices, enabling potential capital gains.

In summary, when the current interest rate is higher than the critical rate, typical wealth-holders prefer to hold government bonds. Conversely, when the current interest rate is lower than the critical rate, they opt to hold cash. When the current interest rate equals the critical rate, wealth-holders are indifferent between holding cash and bonds. This demonstrates that speculative demand for money is inversely related to interest rates.

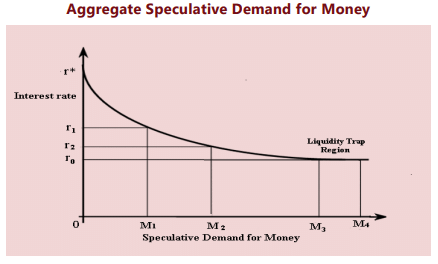

Aggregate Speculative Demand for Money

When we combine individual speculative demands for money into an aggregate, the individual wealth-holder's demand curve becomes smooth and continuous. This reflects a consistent downward-sloping demand function, illustrating the inverse relationship between the current interest rate and the aggregate speculative demand for money.

Keynes' Perspective

- According to economist John Maynard Keynes, when interest rates are high, the speculative demand for money decreases. Conversely, when interest rates are low, the speculative demand for money increases.

Understanding the Liquidity Trap

- A liquidity trap occurs when an increase in the money supply does not lead to higher interest rates, income, or economic growth. It represents the extreme impact of monetary policy.

- In a liquidity trap, the public is willing to hold any amount of money supplied at a given interest rate due to fears of negative events such as deflation or war.

- Under these circumstances, monetary policy, especially through open market operations, becomes ineffective in influencing interest rates or income levels.

Characteristics of a Liquidity Trap

- A liquidity trap is often observed at short-term zero percent interest rates. At this level, the public prefers holding cash, which, like bonds, earns zero interest but is more convenient for transactions.

- This leads to a situation where the speculative demand for money becomes perfectly elastic concerning interest rates, causing the speculative money demand curve to align parallel to the X-axis.

- In essence, the opportunity cost of holding money becomes zero, and even if the monetary authority increases the money supply, individuals prefer to hoard cash rather than invest.

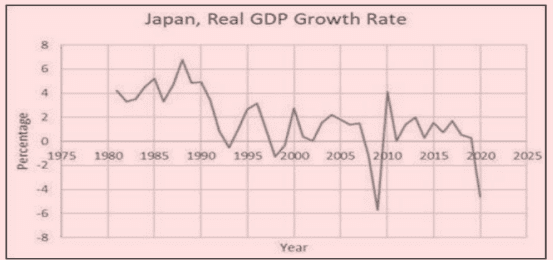

The Bank of Japan's Experience

- A real-world example of the liquidity trap is seen in Japan, where the central bank's money printing led to hoarding in anticipation of further deflation, rather than increased investment.

- This phenomenon is illustrated by Japan's 10-year bond yield dropping to a historic low of 0.2 percent.

Post-Keynesian Developments in the Theory of Demand for Money

Post-Keynesian theories of the demand for money primarily focus on its role as a store of value or an asset.

Inventory Approach to Transaction Balances

Baumol (1952) and Tobin (1956) introduced a deterministic theory of transaction demand for money known as the Inventory Theoretic Approach. In this framework, money, or 'real cash balance,' is viewed as an inventory held for transaction purposes.

Key Assumptions of Inventory Models:

- Media for Storing Value:Inventory models assume the existence of two media for storing value:

- Money (or real cash balance)

- An interest-bearing alternative financial asset, such as bank deposits

- Transfer Costs: There is a fixed cost associated with making transfers between money and alternative assets, such as broker charges.

- Liquidity and Returns: While relatively liquid financial assets (e.g., bank deposits) offer a positive return, the transaction cost of transferring between money and these assets justifies holding money.

Baumol's Approach to Demand for Money:

- Inventory Perspective: Baumol proposed that individuals hold an inventory of money for transaction purposes. He emphasized the need for maintaining an optimum inventory of money to meet day-to-day transaction needs.

- Opportunity Cost: Holding money incurs a cost, which is the interest forgone by not investing in interest-bearing assets (e.g., savings deposits, fixed deposits, bonds, or shares). This forgone interest is known as the opportunity cost.

- Safety and Risk: Money held in the form of currency and demand deposits is safe and riskless but does not earn interest. In contrast, bonds and shares may provide returns but carry risks, including potential capital loss. Savings deposits are safe and risk-free but offer some interest.

- Convenience: Baumol questioned why people hold money in the form of currency or demand deposits instead of safer alternatives like savings deposits that earn interest. He argued that it is due to the convenience and ease of using money for transactions.

- Interest Rates and Transaction Demand: Baumol and Tobin suggested that transaction demand for money is influenced by interest rates. As interest rates on savings deposits increase, people are likely to hold less money in the form of currency or demand deposits, and vice versa.

- Cost-Benefit Comparison: Individuals compare the costs and benefits of holding money (which earns no interest) with holding savings deposits (which earn interest). The opportunity cost of holding money is a crucial factor in this comparison.

Baumol's Model: Average Cash Withdrawal

- According to Baumol, the average amount of cash withdrawal that minimizes cost is calculated using the formula: C = √2bY/r

- In this formula:

- C = Average cash withdrawal amount

- b = Broker's fee

- Y = Individual's income

- r = Interest rate

- This concept is known as the Square Root Rule.

Demand for Money and Bonds

- The inventory-theoretic approach indicates that the demand for money and bonds is influenced by the cost of transferring between these assets, such as the brokerage fee.

- When the brokerage fee increases:

- The marginal cost of bond market transactions rises, leading to a decrease in the number of such transactions.

- The transactions demand for money increases, and the average bond holding decreases.

- This is because a higher brokerage fee makes it more expensive to temporarily switch funds into bond holdings.

- Individuals optimize their asset portfolio of cash and bonds to minimize the overall cost of holding these assets.

Friedman's Restatement of the Quantity Theory

Milton Friedman's Extension: In 1956, Milton Friedman expanded upon Keynes' concept of speculative money demand within the framework of asset price theory. He viewed the demand for money as part of a broader theory of capital asset demand.

Factors Influencing Demand:According to Friedman, the demand for money is influenced by the same factors that affect the demand for any asset, including:

- Permanent Income: Friedman argued that it is permanent income, rather than current income as suggested by Keynes, that determines the demand for money. Permanent income represents the expected value of all future income and is a measure of wealth.

- Relative Returns on Assets: This factor includes the risk associated with different assets.

Money as a Durable Good: Friedman regarded money as a durable consumption good, similar to other assets. Therefore, its demand is influenced by various factors, just like the demand for any other durable good.

Determinants of Nominal Demand for Money:Friedman identified several key determinants of nominal demand for money:

- Total Wealth: Nominal demand for money is related to total wealth, which is permanent income divided by the discount rate. The discount rate is the average return on five asset classes: money, bonds, equity, physical capital, and human capital.

- Price Level: There is a positive relationship between demand for money and the price level. When the price level rises, demand for money increases, and vice versa.

- Opportunity Costs: Demand for money rises when the opportunity costs of holding money (returns on bonds and stocks) decline, and vice versa.

The Demand for Money as an Asset

According to Keynes' liquidity preference theory, money is considered a "liquid asset" that is held for transaction purposes. However, there are other assets, such as bonds and shares, that can also be considered as "near money" assets. These assets can be easily converted into cash and are therefore considered as part of the money supply. The demand for money as an asset is influenced by various factors, including the rate of interest and the level of income. When the rate of interest is high, people tend to hold more bonds and shares, as they offer better returns. Conversely, when the rate of interest is low, people tend to hold more cash, as it is more liquid and easily accessible.

The Demand for Money as Behaviour toward Risk

James Tobin, an American economist, made significant contributions to the understanding of how individuals manage their wealth and the role of money in their portfolios. He proposed that people have a preference for more wealth rather than less and face the challenge of deciding how to allocate their financial assets between liquid money (which earns no interest) and interest-earning investments like bonds, and potentially riskier assets like shares.

Tobin's key insights include:

- Portfolio Diversification: Individuals diversify their portfolios by holding a mix of safe and risky assets. This means they don't put all their money into high-risk investments but instead balance their holdings to manage risk.

- Risk Aversion: People tend to be risk-averse, meaning they prefer to take on less risk for a given level of return. For example, an investor who holds a larger proportion of risky assets like bonds or shares in their portfolio may earn a higher average return, but they also face greater risk. Tobin argues that a risk-averse individual would not choose a portfolio with only risky bonds or a higher proportion of them.

- Riskless Assets: On the other hand, an individual who holds only safe and riskless assets like cash or demand deposits is taking almost no risk but also receiving no return. This highlights the trade-off between risk and return in portfolio management.

- Mixed Portfolio Preference: People generally prefer a mixed or diversified portfolio that includes money, bonds, and shares, with each person choosing a different balance between risk and return based on their preferences and risk tolerance.

Tobin's Liquidity Preference Function

Tobin developed the liquidity preference function, which illustrates the relationship between the rate of interest and the demand for money. He argued that as the rate of return on bonds increases, individuals are more inclined to hold a larger portion of their wealth in bonds and less in the form of cash. Key points of Tobin's Liquidity Preference Function:

- Higher Interest Rates: When interest rates are high, the demand for holding money decreases, and people tend to hold more bonds in their portfolios.

- Lower Interest Rates: Conversely, when interest rates are low, the demand for money increases, and people hold less in the form of bonds.

- Downward Sloping Demand Function: In Tobin's portfolio approach, the demand function for money as an asset slopes downward, indicating that as the interest rate on bonds falls, the asset demand for money in people's portfolios increases.

- Aggregate Liquidity Preference Curve: Tobin derived the aggregate liquidity preference curve by assessing how changes in interest rates affect the asset demand for money in people's portfolios.

Conclusion

1. Tobin’s liquidity preference theory has been validated by empirical studies measuring the interest elasticity of money demand as an asset.

2. Different theories offer valuable insights into money demand, with Fisher emphasizing money supply’s role in price determination, Cambridge linking real money demand to real income, and Keynes introducing interest rates as a factor.

3. Despite variations in countries’ money demand determinants, a positive relationship with real income and an inverse relationship with interest rates are common across theories.

4. Empirical evidence is necessary to support theoretical propositions, and key predictors of money demand include real income, interest rates, and inflation expectations.

|

86 videos|255 docs|58 tests

|

FAQs on Unit 1: The Concept of Money Demand: Important Theories Chapter Notes - Business Economics for CA Foundation

| 1. What is fiat money and how does it differ from commodity money? |  |

| 2. How is the demand for money measured in economic terms? |  |

| 3. What is the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) and its significance? |  |

| 4. What are the main components of the Keynesian Theory of Demand for Money? |  |

| 5. How does Friedman's Restatement of the Quantity Theory differ from the classical approach? |  |