The Companies Act, 2013 Chapter Notes | Business Laws for CA Foundation PDF Download

Overview

Introduction

The Companies Act of 2013 was established to update and streamline the laws governing companies in India. It replaced the earlier Companies Act of 1956 due to the evolving national and international economic landscape and the need to support economic growth. The 2013 Act, which consists of 470 sections and seven schedules divided into 29 chapters, aims to enhance corporate governance, simplify regulations, and protect minority investors.

Additionally, it introduces measures for whistle-blowers and class action suits, making corporate regulations more relevant to contemporary needs.

Applicability of the Companies Act, 2013:

The Companies Act, 2013 applies to various entities, including

- Companies formed under this Act or earlier company laws.

- Insurance firms, unless conflicting with the Insurance Act, 1938 or the IRDA Act, 1999.

- Banking institutions, unless conflicting with the Banking Regulation Act, 1949.

- Companies involved in electricity generation or supply, unless conflicting with the Electricity Act, 2003.

- Other companies governed by specific laws.

- Bodies corporate established by current Acts, as notified by the Central Government.

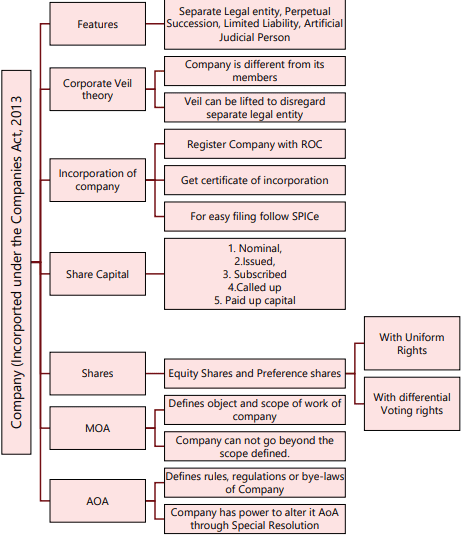

Company: Meaning and Features

Meaning: A corporation, as described by Chief Justice Marshall, is a legal creation—an invisible and intangible entity that exists only in the eyes of the law. It has no properties other than those granted by its charter, either explicitly or as a necessary part of its existence. Professor Haney adds that a company is an incorporated group, an artificial person with a separate legal identity, perpetual existence, and a common seal.The Companies Act, 2013 defines a "company" as one incorporated under this Act or previous company laws. This chapter will further clarify the meaning of "company."

Features of a Company

I. Separate Legal Entity:- A company is legally distinct from its members.

- It has its own legal identity, separate from those who own it.

- A company can own property, open bank accounts, borrow money, and enter into contracts in its own name.

- Members of the company can contract with the company, but the company is separate from its members.

- Only the company’s creditors can sue the company for its debts, not its members.

Legal Insurable Interest in Company Property

Legal insurable interest in company property is a crucial aspect when it comes to insurance claims. A leading case that illustrates this principle is Macaura Vs. Northern Assurance Co. Limited (1925).

Facts of the Case

In the case of Macaura Vs. Northern Assurance Co. Limited, Macaura (M) held nearly all the shares of a timber company, except for one. He was also a significant creditor of the company. M insured the company’s timber in his own name. When the timber was lost in a fire, M filed a claim for insurance compensation.

Legal Principle: The court held that the insurance company was not liable to M because no shareholder has a legal right to any property owned by the company. M did not have a legal or equitable interest in the timber.

Insurable Interest: In this case, since the timber was not insured in the company’s name, M could not claim compensation from the insurance company. This highlights the importance of legal insurable interest in insurance claims related to company property.

II. Perpetual Succession

Definition: Perpetual succession refers to the continuous existence of a company, regardless of changes in its membership. Members may die or change, but the company continues to exist until it is legally wound up.

Legal Basis: A company is an artificial person created by law, and only the law can bring an end to its life. The existence of a company is not affected by the death or insolvency of its members.

Example 1: Many companies in India have existed for over a century due to perpetual existence. For instance, a company with seven members who all died in an aircraft accident continued to exist, unlike a partnership that would dissolve upon the death of its members.

III. Limited Liability

Limited Liability Company: In a limited liability company, the debts of the company do not become the personal debts of the shareholders. The liability of the members is limited to the extent of the nominal value of shares held by them. Shareholders cannot be asked to pay more than the unpaid value of their shares.

Company Limited by Guarantee: Members are liable only to the extent of the amount guaranteed by them, and this liability arises only when the company goes into liquidation.

Unlimited Company: The liability of members is unlimited, meaning they can be held personally liable for the debts of the company without any limit.

IV. Artificial Legal Person

(i) A company is considered an artificial person because it is formed through a legal process, not by natural birth. It is also a legal or judicial person because it is created by law. The term "person" applies to a company because it has been granted all the rights of an individual.

(ii) Being a separate legal entity, a company has the ability to own property, maintain a bank account, obtain loans, incur liabilities, and enter into contracts. Members of the company can also enter into contracts with the company, gain rights against it, or incur liabilities to it. A company can sue and be sued in its own name, and it can perform almost all the activities that a natural person can, except for being imprisoned, taking an oath, getting married, or practicing a regulated profession. This is why it is considered a legal person in its own right.

(iii) However, since a company is an artificial person, it can only act through human agents, such as directors. The directors do not have control over the company’s affairs or act as agents for the company’s members. Instead, they can authenticate the company’s formal actions either on their own or using the company’s common seal.

(iv) Therefore, a company is categorized as an artificial legal person.

V. Common Seal

- A company, being an artificial entity, lacks the physical presence of a natural being. As a result, it operates through the agency of human individuals. The common seal serves as the official signature of a company, affixed by its officers and employees on various documents. It symbolizes the company’s incorporation and is used as a mark of authenticity.

- The Companies (Amendment) Act, 2015 made the common seal optional by removing the requirement for it in Section 9. This change allows companies to choose an alternative method of authorization instead of using a common seal. The rationale behind this amendment is that the common seal is viewed as an outdated practice. Similarly, in the UK, the use of a common seal has been optional since 2006.

- According to the amendment, companies that wish to use a common seal must do so voluntarily. If a company does not have a common seal, documents that would typically require it can be authorized by two directors or by a director and the Company Secretary, if one has been appointed.

Corporate Veil Theory

(i) Corporate Veil : The Corporate Veil is a legal principle that distinguishes the company as a separate entity from its members. It protects members from being held liable for the company’s debts or legal violations. In simpler terms, it means that if a company gets into financial trouble or breaks the law, its members are not personally responsible for those issues. This concept provides members with a shield from liability, ensuring they are insulated from the company’s actions.

In this way, the interests of shareholders are safeguarded from the company's actions.

The case of Salomon v. Salomon and Co Ltd. established the principle of the corporate veil and the idea of independent corporate personality.

In Salomon v. Salomon & Co. Ltd., the House of Lords determined that a company is a legal entity separate and distinct from its members. In this case, Mr. Salomon formed a company called "Salomon & Co. Ltd." with seven subscribers: himself, his wife, four sons, and one daughter. The company acquired Salomon's personal business assets for £38,782, and in return, Salomon received 20,000 shares of £1 each, debentures worth £10,000 secured by the company's assets, and cash. His wife, daughter, and four sons each took one £1 share. Later, the company faced liquidation due to a general trade downturn. Unsecured creditors totaling £7,000 argued that Salomon should not be considered a secured creditor because he was the managing director of a one-man company, essentially the same as Salomon himself, and claimed that the company was a mere facade and fraud. Lord Mac Naughten ruled:

“The Company is at law a different person altogether from the subscribers to the memorandum, and though it may be that after incorporation the business is precisely the same as it was before and the same persons are managers, and the same hands receive the profits, the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or trustees for them. Nor are the subscribers, as members, liable, in any shape or form, except to the extent and in the manner provided by the Act.”

This ruling affirmed that a company possesses its own legal identity, and shareholders cannot be held responsible for the company's actions, even if they own nearly all the shares. The entire framework of corporate law is built on this concept of separate corporate entity.

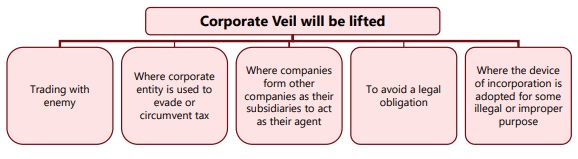

Lifting the Corporate Veil:The term “lifting the veil” refers to the act of looking beyond the company as a separate legal entity and considering the actual individuals behind it. This means disregarding the corporate entity and focusing on the real people involved, such as members or managers. However, courts are only willing to lift the corporate veil in specific circumstances, particularly when issues of control are at stake, rather than just ownership.

Instances Where Corporate Veil Can Be Lifted:

- Testing Friendship or Enmity: In cases like trading with the enemy, the court assesses whether a company acts as a friend or foe by examining who controls it. A leading case is Daimler Co. Ltd. vs. Continental Tyre & Rubber Co.

- Protecting Revenue and Tax: Courts may disregard the corporate entity in tax matters, such as S. Berendsen Ltd. vs. Commissioner of Inland Revenue, or when the corporate structure is used to evade tax, as in Juggilal vs. Commissioner of Income Tax.

- Identifying Sham Companies: In cases like Dinshaw Maneckjee Petit, the court may lift the corporate veil to reveal the true owner of income when companies are deemed not genuine.

Supreme Court's Decision to Pierce the Corporate Veil:

- The Supreme Court upheld the piercing of the corporate veil in this case to avoid a legal obligation.

- The court found that the company was formed solely with the intention of reducing the bonus payments to its workers.

- This led to the decision to disregard the separate legal entity of the company and hold the individuals behind it accountable.

- The corporate veil was pierced because the company's primary purpose was to limit the bonuses paid to its employees, which the court deemed an improper use of the corporate structure.

Case Study: Workmen of Associated Rubber Industry Ltd. v. Associated Rubber Industry Ltd.

- Background: In this case, "A Limited" invested ₹4,50,000 in shares of "B Limited." The dividends from these shares were consistently reported in A Limited's profit and loss account and were considered when calculating bonuses for the company's workers.

- Transfer of Shares: In 1968, A Limited transferred its shares in B Limited to its wholly-owned subsidiary, C Limited. This transfer meant that the dividend income was no longer included in A Limited's profit and loss account, reducing the surplus available for worker bonuses.

- Supreme Court's Decision: The Supreme Court intervened because the subsidiary, C Limited, was created solely to reduce A Limited's bonus liabilities. C Limited had no assets, business, or income of its own, except for the dividends from the shares transferred to it by A Limited. The court disregarded the subsidiary's separate legal existence, highlighting that it served no purpose other than to minimize A Limited's profits and, consequently, its bonus obligations to workers.

- Formation of Subsidiaries as Agents: In some cases, a company may be seen as an agent or trustee for its members or another company, losing its individuality in favor of its principal. In such instances, the principal becomes liable for the actions of the subsidiary.

Example: Merchandise Transport Limited vs. British Transport Commission (1982)

- A transport company needed licenses for its vehicles but faced difficulties applying in its own name. To overcome this, it formed a subsidiary and submitted the license application in the subsidiary's name. The vehicles were intended to be transferred to the subsidiary.

- The court ruled that the parent and subsidiary companies operated as a single commercial unit, leading to the rejection of the license applications.

Company Formation for Fraud or Improper Conduct: Incorporating a company for illegal or improper purposes, such as evading law, defrauding creditors, or avoiding legal obligations, can lead to lifting the corporate veil. An example is the case of Gilford Motor Co. vs. Horne.

Situations for Lifting Corporate Veil: Corporate veil may be lifted in cases of trading with the enemy, tax evasion, forming subsidiaries as agents, avoiding legal obligations, or adopting incorporation for illegal purposes.

Classes of Companies Under the Companies Act, 2013

The Companies Act, 2013 classifies companies into various categories based on their characteristics and the nature of their operations. This classification is necessary to regulate the different forms of corporate organizations that have emerged due to the growth of the economy and the increasing complexity of business operations.1. Basis of Incorporation:

- One-Person Company: A company with a single member.

- Private Company: A company that restricts the right to transfer its shares and limits the number of its members.

- Public Company: A company that is not a private company and is eligible to offer its shares to the public.

2. Basis of Liability:

- Company Limited by Shares: A company where the liability of its members is limited to the amount unpaid on their shares.

- Company Limited by Guarantee: A company where the liability of its members is limited to the amount they guarantee to contribute to the assets of the company in the event of its winding up.

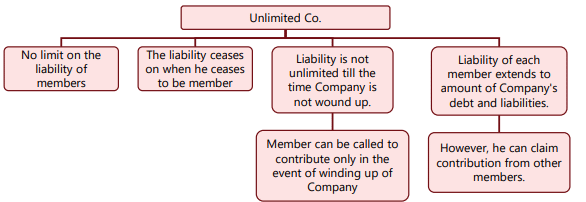

- Unlimited Company: A company where there is no limit on the liability of its members.

3. Basis of Control:

- Holding Company: A company that holds a controlling interest in another company.

- Subsidiary Company: A company that is controlled by a holding company.

- Associate Company: A company in which another company has a significant influence, typically through ownership of a substantial portion of its shares.

4. Other Classifications:

- Foreign Company: A company incorporated outside India but operating in India.

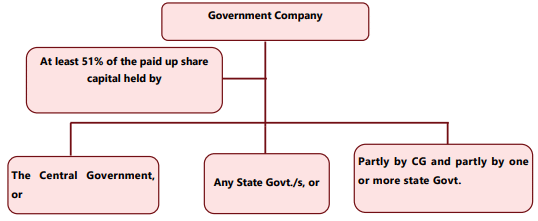

- Government Company: A company in which the government holds at least 51% of the shares.

- Small Company: A private company that meets certain criteria regarding its turnover and paid-up capital.

- Dormant Company: A company that is inactive and not carrying on any business or operations.

- Nidhi Company: A company that is formed to encourage savings among its members and to lend money to them.

- Company formed for Charitable Objects: A company established for promoting charitable purposes.

Different Types of Companies

Companies can be classified in various ways. One of the bases for classification is the liability of members.1. Company Limited by Shares:

- According to Section 2(22) of the Companies Act, 2013, a company limited by shares is one where the liability of its members is limited to the amount unpaid on the shares they hold.

- This means that shareholders are only responsible for the company’s debts up to the amount they owe on their shares. Their personal property cannot be used to cover the company’s debts.

- It’s important to note that while shareholders are co-owners of the company, they do not own the company’s assets. The company, as a legal entity, owns its assets. A shareholder’s rights and responsibilities are determined by their shareholdings.

2. Company Limited by Guarantee:

- A company limited by guarantee, as defined in Section 2(21) of the Companies Act, 2013, is one where the liability of its members is limited to a specific amount they agree to contribute to the company’s assets in the event of winding up.

- Members cannot be asked to contribute more than this agreed amount.

- Both guarantee companies and companies with share capital have legal personality and limited liability. However, in guarantee companies, members’ liabilities are called upon only after winding up begins, while in share capital companies, liabilities can be called at any time.

- Guarantee companies do not raise initial funds from their members, making them suitable for situations where no working funds are needed or where funds can be obtained from other sources like donations or fees.

In the case of Narendra Kumar Agarwal vs. Saroj Maloo, the Supreme Court clarified that a guarantee company has different rights regarding the transfer of membership interests compared to a company limited by shares. Membership in a guarantee company may come with different privileges than those of ordinary shareholders.

Unlimited Company:

- An unlimited company, as per Section 2(92) of the Companies Act, 2013, is a type of company where there is no limit on the liability of its members. In this kind of company, a member's liability continues until they cease to be a member.

- The liability of each member covers the entire amount of the company's debts and liabilities. However, this liability can only be enforced when the company is being wound up.

- If the company has share capital, the Articles of Association must specify the amount of share capital and the value of each share. While the company is operational, the only liability that can be enforced is related to the shares.

- Creditors have the right to initiate winding-up proceedings to claim their debts. During this process, the official liquidator may call upon members to contribute towards the company's liabilities and debts, which can be unlimited.

- In an unlimited company, the liability of members is not considered unlimited until the company is wound up. Each member's liability extends to the company's debts and liabilities, but they can seek contributions from other members.

Based on Members

(i) One Person Company: The Companies Act, 2013 introduced a new type of company that can be formed by a single individual.

- Definition: According to Section 2(62) of the Companies Act, 2013, a One Person Company (OPC) is defined as a company with only one member.

- Purpose: OPCs were introduced to promote entrepreneurship and the incorporation of businesses. Unlike sole proprietorships, an OPC is a separate legal entity with limited liability for its member. In a sole proprietorship, the owner's liability is unlimited, extending to personal and business assets.

- Procedural Simplification: The procedural requirements for OPCs are simplified compared to other company forms, with exemptions provided under the Act.

- Nature of OPC: An OPC is considered a private limited company with a minimum paid-up share capital as prescribed, having only one member.

- Membership: An OPC can have only one member.

- Paid-up Capital: There is no prescribed minimum paid-up capital, but it must comply with minimum capital requirements set by relevant authorities in specific cases.

- Nominee Provision: The memorandum of the OPC must indicate the name of another person who will become a member in the event of the subscriber's death or incapacity. This person must provide prior written consent, which is filed with the Registrar of Companies during incorporation.

- Eligibility: Only a natural person who is an Indian citizen, whether resident in India or not a resident, can incorporate an OPC or be a nominee for sole member of a OPC.

- Restrictions: No individual can incorporate more than one OPC or be a nominee in more than one such company. Minors cannot be members or nominees of an OPC or hold shares with beneficial interest.

- Conversion: An OPC cannot be incorporated or converted into a company under section 8 of the Act, but it may be converted to private or public companies in certain cases.

Companies that fall under this category are not permitted to engage in Non-Banking Financial Investment activities, which includes investing in securities of any corporate entity.

In this context, the term "member" can refer to both the sole member and the director of the company.

(ii) Private Company in nature

Exemptions are designed to streamline procedural requirements.

Private company [Section 2(68)]:

- A "private company" is defined as a company with a minimum paid-up share capital, as prescribed, and which, by its articles, restricts the right to transfer its shares.

- Member Limit: Except in the case of a One Person Company (OPC), the number of members is limited to 200. Joint holders of shares are treated as a single member for this purpose.

- Exclusions:The number of members does not include:

- Persons in the employment of the company.

- Former employees who were members while in employment and have continued as members after their employment ceased.

- Public Invitation: The company prohibits any invitation to the public to subscribe for its securities.

Key Points about Private Companies:

- Paid-up Capital: There is no minimum paid-up capital requirement for private companies.

- Members: The minimum number of members is 2, except for OPCs, where it is 1. The maximum number of members is 200, excluding present and former employee members.

- Share Transfer: The right to transfer shares is restricted.

- Securities Invitation: Private companies are prohibited from inviting the public to subscribe to their securities.

OPC Formation: A One Person Company (OPC) can only be formed as a private company.

Small Company Definition

A small company is defined under Section 2(85) of the Companies Act, 2013, as a company (other than a public company) that meets the following criteria:

- Paid-up Share Capital: Does not exceed fifty lakh rupees or a higher amount prescribed, which shall not exceed ten crore rupees.

- Turnover: Does not exceed two crore rupees or a higher amount prescribed, which shall not exceed one hundred crore rupees, as per the profit and loss account for the immediately preceding financial year.

- Exceptions:The definition of a small company does not apply to:

- Holding companies or subsidiary companies.

- Companies registered under section 8 of the Companies Act.

(iii) Public Company:

- A public company is one that is not a private company and has a minimum paid-up share capital as prescribed by regulations.

- Public companies have no restrictions on the transfer of shares and do not have a minimum paid-up capital requirement.

- They must have a minimum of 7 members, and there is no limit on the maximum number of members.

- Subsidiaries of public companies are deemed to be public companies themselves.

Classification of Companies Based on Control

(a) Holding and Subsidiary Companies :Holding Company : A holding company is one that has control over other companies, known as its subsidiaries. This control can be through:

- Controlling the Board of Directors of the subsidiary.

- Holding more than 50% of the voting power, either directly or through its subsidiaries.

Subsidiary Company : A subsidiary company is one that is controlled by a holding company. This can be through:

- Control of the Board of Directors.

- Holding more than 50% of the voting power.

Important Points :

- A company can be considered a subsidiary of a holding company even if the control is exercised by another subsidiary of the holding company.

- A company’s Board of Directors is deemed to be controlled by another company if that company can appoint or remove the majority of the directors.

- The term “company” in this context refers to any body corporate.

- A “layer” in relation to a holding company refers to its subsidiary or subsidiaries.

Examples:

- Example 1: If Company B controls the Board of Directors of Company A, then A is a subsidiary of B.

- Example 2: If Company B holds more than 50% of the share capital of Company A, then A is a subsidiary of B.

- Example 3: If Company B is a subsidiary of Company A, and Company C is a subsidiary of Company B, then Company C is also a subsidiary of Company A. This chain of subsidiaries can continue, where if Company D is a subsidiary of Company C, then D is also a subsidiary of Company B and Company A.

Status of Private Companies:

- A private company that is a subsidiary of a public company is considered a public company under the Companies Act, 2013, even if it remains a private company in its articles of association.

(b) Associate Company:

Definition: An associate company is one in which another company has significant influence but does not have full control, meaning it is not a subsidiary. This also includes joint venture companies.

Explanation of Terms

- Significant Influence: This refers to the ability to control at least 20% of the total voting power in a company or to participate in business decisions as per an agreement.

- Joint Venture: A joint venture is an arrangement where parties with joint control have rights to the net assets of the arrangement.

Companies on the Basis of Access to Capital

(a) Listed Companies- A listed company, as per section 2(52) of the Companies Act, 2013, is one whose securities are listed on a recognized stock exchange in India.

- The term "securities" is defined in section 2(81) of the Companies Act, 2013, and is aligned with the definition in clause (h) of section 2 of the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act, 1956.

Example 5: Scan Steel Rods Limited is a listed company because its shares are traded on the Stock Exchange in Kolkata, following a Listing Agreement with the exchange.

(b) Unlisted Companies

An unlisted company is any company that does not meet the criteria of a listed company, meaning its securities are not listed on a recognized stock exchange.

Other Companies

Government Company [Section 2(45)]: A Government Company is defined as any company in which not less than 51% of the paid-up share capital is held by:- the Central Government, or

- by any State Government or Governments, or

- partly by the Central Government and partly by one or more State Governments.

The definition also includes a company that is a subsidiary of such a Government Company.

Explanation: For the purposes of this definition, "paid-up share capital" shall be understood as "total voting power" in cases where shares with differential voting rights have been issued.

Foreign Company [Section 2(42)]: A Foreign Company refers to any company or body corporate that is incorporated outside India and meets the following criteria:

- Has a place of business in India, either by itself or through an agent, whether physically or through electronic means; and

- Conducts any business activity in India in any other manner.

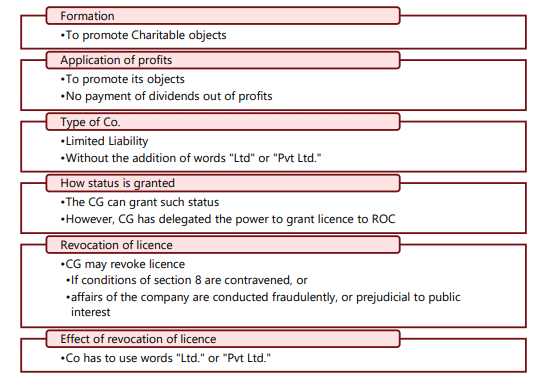

Formation of Companies with Charitable Objects (Section 8 Company): Section 8 of the Companies Act, 2013 governs the formation of companies aimed at promoting charitable objects such as commerce, art, science, sports, education, research, social welfare, religion, charity, environmental protection, etc.

Objectives and Profit Application: Such companies intend to apply their profits towards promoting their objects and are prohibited from paying any dividends to their members.

Examples: Notable examples of Section 8 companies include FICCI, ASSOCHAM, National Sports Club of India, and CII.

Power of Central Government to Issue Licenses

Registration without 'Limited' or 'Private Limited'

- Section 8 empowers the Central Government to register individuals or associations as companies with limited liability without including 'Limited' or 'Private Limited' in their name.

- The Central Government can issue a license with specific conditions it deems fit.

Privileges and Obligations: Upon registration, the company enjoys the same privileges and obligations as a limited company.

Revocation of License: The Central Government can revoke the company’s license if it violates any requirements or conditions, conducts affairs fraudulently, violates its objects, or acts against public interest.

Process of Revocation: Before revocation, the Central Government must provide written notice of its intention and an opportunity for the company to be heard.

Change of Name: Upon revocation, the Registrar will change the company’s name to ‘Limited’ or ‘Private Limited.’

Order of the Central Government

When a license is revoked, the Central Government may, in the public interest, order the amalgamation of the company with another company sharing similar objectives, to form a single entity with specified constitution, properties, powers, rights, interests, authorities, privileges, liabilities, duties, and obligations, or may direct the company to be wound up.

Penalty for Contravention:

- Company Penalty: A company defaulting in compliance with the requirements of this section shall be punishable with a fine ranging from a minimum of ten lakh rupees to a maximum of one crore rupees.

- Director and Officer Penalty: Directors and officers in default shall be punishable with a fine ranging from a minimum of twenty-five thousand rupees to a maximum of twenty-five lakh rupees.

- Fraudulent Conduct: If the company’s affairs were conducted fraudulently, every officer in default shall be liable for action under section 447.

Section 8 Company - Key Points

- Purpose: Formed to promote commerce, art, science, religion, charity, environmental protection, sports, etc.

- Minimum Share Capital: This requirement does not apply specifically to Section 8 companies.

- Profit Utilization: Profits are used for promoting the objective for which the company is formed.

- Dividend Declaration: Section 8 companies do not declare dividends to members.

- Government License: Operates under a special license from the Central Government.

- Name Specification: Not required to include "Ltd." or "Pvt. Ltd." in its name; may adopt a more suitable name such as club, chambers of commerce, etc.

- License Revocation: License can be revoked if conditions are contravened.

- Post-Revocation Options: On revocation, the Central Government may direct the company to convert its status and change its name, wind up, or amalgamate with another company having a similar object.

- General Meeting Notice: Can call its general meeting with a clear 14 days’ notice instead of the usual 21 days.

- Director Requirements: The requirement of a minimum number of directors, independent directors, etc. does not apply.

- Committee Requirements: Need not constitute a Nomination and Remuneration Committee and a Shareholders Relationship Committee.

- Membership: A partnership firm can be a member of a Section 8 company.

Purpose of Section 8 Company:

- To promote charitable objects: Section 8 companies are formed with the primary aim of promoting objects that are charitable in nature.

- To promote its objects: The company is dedicated to promoting the specific objects for which it is established.

Dormant Company (Section 455)

- A dormant company is one that is formed and registered for a future project or to hold an asset or intellectual property, and has not had any significant accounting transactions.

- Such a company can apply to the Registrar for dormant status if it meets the criteria.

Inactive Company

- An inactive company is defined as one that has not been carrying on any business or operations, has not made any significant accounting transactions in the last two financial years, or has not filed financial statements and annual returns during the same period.

Significant Accounting Transaction

- A significant accounting transaction includes any transaction other than:

- Payment of fees to the Registrar.

- Payments to fulfill legal requirements.

- Allotment of shares as per legal requirements.

- Payments for office and record maintenance.

Nidhi Companies (Section 406(1))

- Nidhi Companies, also known as Mutual Benefit Societies, are companies declared by the Central Government to promote savings and thrift among members.

Public Financial Institutions (PFI)

- The Companies Act, 2013 recognizes certain institutions as public financial institutions, including:

- Life Insurance Corporation of India.

- Infrastructure Development Finance Company Limited.

- Institutions specified in the Unit Trust of India (Transfer of Undertaking and Repeal) Act, 2002.

- Institutions notified by the Central Government under the Companies Act, 1956.

- Other institutions notified by the Central Government in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India.

Conditions for Notification as PFI

- An institution can be notified as a PFI if it is established by a Central or State Act or if at least 51% of its paid-up share capital is held or controlled by the Central Government or State Governments.

Mode of Registration/Incorporation of Company

(i) Promoters

- Definition: A promoter is a person who is either named in a prospectus or identified by the company in its annual return, has control over the company's affairs, or whose advice the Board of Directors follows.

- Role: Promoters are the individuals who conceive the idea of forming the company and take necessary steps for its registration.

- Exclusion: Professionals acting in a professional capacity, such as solicitors, bankers, and accountants, are not considered promoters.

(ii) Formation of Company

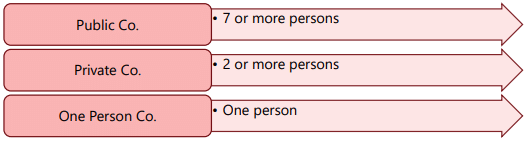

Section 3 of the Companies Act, 2013 deals with the basic requirement with respect to the constitution of the company. In the case of a public company, any 7 or more persons can form a company for any lawful purpose by subscribing their names to memorandum and complying with the requirements of this Act in respect of registration. In the same way, 2 or more persons can form a private company and one person can form one person company

(iii) Incorporation of Company

Filing Requirements: To register a company, certain documents and information must be filed with the registrar within the jurisdiction where the registered office is proposed to be situated.

Documents Required for Company Registration in India

- Declaration from Subscribers and First Directors: A declaration is needed from each subscriber to the memorandum and from any individuals named as the first directors in the articles of association. This declaration should state that:

- No Convictions: The individual has not been convicted of any offence related to the promotion, formation, or management of any company.

- No Fraud or Misfeasance: The individual has not been found guilty of fraud, misfeasance, or any breach of duty to a company under the Companies Act or previous company laws in the last five years.

- Accuracy of Documents: All documents filed with the Registrar for company registration are correct, complete, and true to the best of the individual's knowledge and belief.

- Correspondence Address: The individual must provide an address for correspondence until the registered office is established.

- Particulars of Subscribers: Details of every subscriber to the memorandum, including names, residential addresses, nationalities, and proof of identity. If the subscriber is a body corporate, additional prescribed particulars must be included.

- Particulars of First Directors: Details of the persons mentioned in the articles as subscribers to the memorandum, including names, Director Identification Numbers, residential addresses, nationalities, and proof of identity.

- Interests in Other Firms: Information about the interests of the first directors in other firms or bodies corporate, along with their consent to act as directors of the company.

Registration and Issuance of Certificate:

- Certificate of Incorporation: The Registrar will register the documents and information filed and issue a certificate of incorporation, confirming that the proposed company is incorporated under the Companies Act.

- Corporate Identity Number (CIN): The Registrar will allot a Corporate Identity Number (CIN) to the company, which will serve as a distinct identity for the company. This CIN will be included in the certificate of incorporation.

Maintenance of Documents:

The company is required to maintain and preserve copies of all documents and information as originally filed at its registered office until its dissolution under the Companies Act.

Furnishing of False Information or Suppressing Material Facts during Incorporation

At the Time of Incorporation:

- If a person provides false or incorrect information or hides important facts while filing documents for company registration with the Registrar, they can be held liable for fraud under section 447.

After Incorporation:

- If it is proven that a company was incorporated by providing false information or by suppressing material facts in the documents or declarations filed for its incorporation, the promoters, first directors, and those making declarations are liable for fraud under section 447.

Order of the Tribunal:

- If a company is found to be incorporated by false information or suppression of material facts, the Tribunal can take various actions such as:

- Regulating the management of the company, including changes to its memorandum and articles in the public interest or in the interest of the company, its members, and creditors.

- Directing unlimited liability for the members.

- Removing the company’s name from the register of companies.

- Ordering the winding up of the company.

- Taking any other appropriate actions.

Before Making Orders:

- The company must be given a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

- The Tribunal should consider the transactions entered into by the company, including any obligations contracted or liabilities incurred.

SPICe: Simplified Proforma for Incorporating Company Electronically

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) has made efforts to facilitate business operations by simplifying the process of filing forms for company incorporation through the Simplified Proforma for Incorporating a Company Electronically (SPICe). This initiative aims to make it easier to set up businesses in India.Effect of Registration:

- Section 9 of the Companies Act, 2013 outlines the effects of registering a company.

- From the date of incorporation specified in the certificate of incorporation, the subscribers to the memorandum and future members become a body corporate with the name mentioned in the memorandum.

- A registered company can exercise all functions of an incorporated entity, including perpetual succession, acquiring and disposing of property, entering into contracts, and legal actions under its name.

Legal Personality and Separate Existence:

- Upon incorporation, the company becomes a legal person distinct from the incorporators. A binding contract exists between the company and its members as per the Memorandum and Articles of Association.

- The company enjoys perpetual existence until dissolved through liquidation or removal from the register. Shareholders do not own interests in the company’s property, but legal actions may be taken in specific cases.

- A legal personality is established at the time of company registration. The subscribers to the Memorandum of Association and new members are considered a body corporate, and the legal entity begins operations.

- Registered companies have separate existences, recognized by law as legal persons distinct from their members. This principle is evident in cases like State Trading Corporation of India vs. Commercial Tax Officer .

Company Ownership and Juristic Entity:

- Companies can acquire shares in other companies, potentially becoming controlling entities. However, acquiring all shares of another company does not eliminate its corporate status, as each company remains a separate juristic entity. This principle is illustrated in cases like Spencer & Co. Ltd. Madras vs. CWT Madras .

Legal Recognition of Companies:

- The law views a registered company as a separate legal entity, distinct from its members.

- It does not matter if the entire share capital is provided by the Central Government or if all shares are held by the President of India and other Central Government officials.

- This does not change the status of the company or make it an agent of the President or the Central Government, as established in the case of Heavy Electrical Union vs. State of Bihar .

Binding Nature of Memorandum and Articles:

- According to Section 10 of the Companies Act, 2013, once registered, the memorandum and articles bind the company and its members.

- They are bound as if they had signed an agreement to adhere to all provisions of the memorandum and articles.

- Any money owed by a member to the company under the memorandum or articles is considered a debt owed to the company.

Classification of Capital

- The term "capital" can mean different things to different people, such as economists, accountants, businessmen, and lawyers.

- In the context of a company limited by shares, capital refers to share-capital, which is the company's capital divided into shares of a fixed amount.

- A share represents an individual's interest in the company's capital, not just a sum of money.

Capital in Company Law:

- Nominal or Authorised Capital: This is the maximum amount of share capital that a company is authorized to have, as stated in its memorandum. It represents the maximum amount the company can raise by issuing shares and is usually set at an amount estimated to cover the company's needs, including working capital and reserve capital.

- Issued Capital: Issued capital refers to the part of authorized capital that the company offers for subscription. It includes shares allotted for consideration other than cash. Companies are required to disclose their issued capital in the balance sheet.

- Subscribed Capital: Subscribed capital is the part of capital that is currently subscribed by the members of the company. It represents the nominal amount of shares taken up by the public. When a company states its authorized capital, it must also disclose its subscribed and paid-up capital to avoid penalties.

- Called-up capital: Section 2(15) of the Companies Act, 2013 defines “called-up capital” as such part of the capital, which has been called for payment. It is the total amount called up on the shares issued.

- Paid-up capital is the total amount paid or credited as paid up on shares issued. It is equal to called up capital less calls in arrears.

Shares

- A share, as defined in Section 2(84) of the Companies Act, 2013, represents a portion of a company's share capital and includes stock. It signifies the proportion of interest a shareholder has in the company's assets, based on the amount paid up compared to the total capital payable to the company. Essentially, a share measures the interest in the company's assets to which the shareholder is entitled.

- Legal Perspective: Farwell Justice, in the case of Borland Trustees vs. Steel Bors. & Co. Ltd., clarified that a share is not merely a sum of money but an interest quantified by a sum of money, encompassing various rights outlined in the contract, including the right to receive a varying sum of money.

- Ownership Distinction: Shareholders are not considered part owners of the company's undertaking in the eyes of the law. The undertaking is distinct from the collective of shareholders. The rights and obligations associated with a share are specified in the company's memorandum and articles.

- Rights of Shareholders: Shareholders possess both contractual rights and additional rights conferred by the Companies Act. These rights are integral to their relationship with the company and are governed by legal provisions.

- Shares are a type of movable property: According to Section 44 of the Companies Act, 2013, the shares, debentures, or any other interests that a member has in a company are considered movable property. These can be transferred in the way that is specified by the company's articles.

- Shares must be numbered: Section 45 states that each share in a company that has share capital must have a unique number. This means every share should be identifiable by its number. However, this rule does not apply to shares owned by individuals whose names are recorded as holders of a beneficial interest in those shares in the records of a depository.

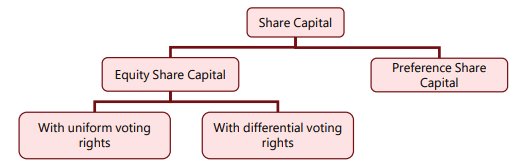

- Types of share capital: Section 43 of the Companies Act, 2013 outlines the types of share capital. It specifies that the share capital of a company limited by shares can be classified into two main types:

Equity share capital:- with voting rights

- with different rights regarding dividends, voting, or other aspects as allowed by the rules

Example 6: It is to be noted that, Tata Motors in 2008 introduced equity shares with differential voting rights called ‘A’ equity shares in its rights issue. In the issue, every 10 ‘A’ equity shares carried only one voting right but would get 5 percentage points more dividend than that declared on each of the ordinary shares. Since ‘A’ equity share did not carry the similar voting rights, it was being traded at discount to other common

Preference share capital: This Act does not change the rights of preference shareholders. They still have the right to receive their share of the proceeds if the company is winding up, even before this Act started.

According to the explanation in section 43:

Equity share capital: For any company that has shares, this term refers to all share capital that is not classified as preference share capital.

Preference share capital: This refers to the part of a company's issued share capital that gives preferential rights regarding:

- Dividend payments: This can be a fixed amount or calculated at a specific rate. These dividends may be subject to income tax or not.

- Repayment of capital: In the event of winding up, this includes the amount of share capital that has been paid up or is considered paid up. This repayment may also include a specified fixed premium or a premium based on a defined scale, as stated in the company's memorandum or articles.

Exception: In certain cases, specific rules or conditions may apply.

Memorandum of Association

The Memorandum of Association (MoA) is a crucial document that serves as the foundation for a company. It outlines the company's constitution, objectives, and the scope of its powers as defined by the Companies Act. Essentially, the MoA is the charter of the company, specifying what the company can and cannot do.

Importance of Memorandum of Association:

- The MoA contains the objectives for which the company is formed, thereby delineating the potential scope of its operations.

- It informs shareholders, creditors, and other stakeholders about the company's powers and the activities it can engage in.

- Being a public document under Section 399 of the Companies Act, 2013, the MoA is accessible to all, and parties entering into contracts with the company are presumed to be aware of its contents.

- The MoA ensures that shareholders are aware of how their money will be used and the risks involved in their investment.

- A company cannot deviate from the provisions of the MoA, even if circumstances demand it. Any action beyond the powers conferred by the MoA is considered ultra vires (beyond the powers) and is void.

Form of Memorandum:

- As per Section 4 of the Companies Act, 2013, the MoA must be drawn up in the form specified in Tables A, B, C, D, and E of Schedule I.

- Table A: For companies limited by shares.

- Table B: For companies limited by guarantee and not having a share capital.

- Table C: For companies limited by guarantee and having a share capital.

- Table D: For unlimited companies.

- Table E: For unlimited companies with share capital.

Content of the Memorandum

The Memorandum of a company must include the following details:

- Name Clause: The name of the company, ending with "Limited" for public companies or "Private Limited" for private companies. This clause does not apply to companies formed under Section 8 of the Act.

- Registered Office Clause: The state where the registered office of the company will be situated.

- Object Clause: The objectives for which the company is being incorporated and any necessary details for furthering these objectives. Companies changing their activities must align their names accordingly within six months of the change.

- Liability Clause: Whether the liability of members is limited or unlimited. For companies limited by shares, it should specify that members' liability is limited to the unpaid amount on their shares. For companies limited by guarantee, it should state the amount each member undertakes to contribute in the event of winding up.

- Capital Clause: The amount of authorized capital divided into shares of fixed amounts and the number of shares agreed to be taken by the subscribers, which should be at least one share. Companies without share capital do not need this clause.

- Association Clause: Details of the subscribers forming the company, including the number of shares taken by each subscriber. In the case of a One Person Company (OPC), the name of the person who will become the member of the company in the event of the subscriber's death.

Signing and Attestation:

- The Memorandum must be printed, divided into numbered paragraphs, and signed by at least seven persons (two for a private company and one for a One Person Company) in the presence of a witness who will attest the signatures.

- The particulars of the signatories and the witness, including their address, description, and occupation, must be recorded.

- A company, being a legal entity, can subscribe to the memorandum through its agent. However, a minor cannot be a signatory as they are not competent to contract. If a guardian subscribes on behalf of a minor, it is deemed to be in their personal capacity.

Additional Provisions:

- Apart from the compulsory clauses, the memorandum may include other provisions, such as rights attached to different classes of shares.

- However, the Memorandum of Association cannot contain anything contrary to the Companies Act provisions, as such clauses would be legally ineffective.

- All other company documents must also comply with the Memorandum's provisions.

Example 7: If you have supplied goods or performed service on such a contract or lent money, you cannot obtain payment or recover the money lent. But if the money advanced to the company has not been expended, the lender may stop the company from parting with it by means of an injunction; this is because the company does not become the owner of the money, which is ultra vires the company. As the lender remains the owner, he can take back the property in specie. If the ultra vires loan has been utilised in meeting lawful debt of the company, then the lender steps into the shoes of the debtor paid off and consequently he would be entitled to recover his loan to that extent from the company.

An act that is ultra vires the company is void and cannot be ratified by the shareholders. However, there are instances where an ultra vires act can be regularized through subsequent ratification:

- Ultra Vires the Directors: If the act is beyond the powers of the directors, the shareholders can ratify it.

- Ultra Vires the Articles: If the act is beyond the articles of the company, the company can amend its articles to validate the act.

- Irregular Acts: If the act is within the powers of the company but is done irregularly, the shareholders can validate it.

Leading Case: Ashbury Railway Carriage and Iron Company Limited v. Riche (1875)

- Facts of the Case: The main objects of the company included making and selling railway carriages, carrying on business as mechanical engineers and general contractors, working mines, and purchasing and selling coal, timber, and metals.

- The directors entered into a contract with Riche to finance the construction of a railway line in Belgium.

- The company ratified the directors’ act by passing a special resolution but later repudiated the contract as being ultra vires.

- Court’s Decision: Riche sued for damages, arguing that the contract was within the company’s powers as general contractors and had been ratified by shareholders.

- The court held the contract null and void, stating that “general contractors” should be read in connection with the company’s main business, which excluded such a contract.

- This case illustrates that an ultra vires contract cannot be binding on the company and cannot become intravires through estoppel, acquiescence, lapse of time, delay, or ratification.

Summary of the Doctrine:

- (i) An act performed is ultra vires the company when it is legal in itself but not authorized by the object clause of the memorandum or by statute, making it null and void.

- (ii) An ultra vires act cannot be ratified even by the unanimous consent of all shareholders.

- (iii) An act that is ultra vires the directors but intra vires the company can be ratified by the members through a resolution at a general meeting.

- (iv) If an act is ultra vires the Articles, it can be ratified by altering the Articles through a Special Resolution at a general meeting.

Disadvantages of the Doctrine:

- The disadvantages of the doctrine of ultra vires outweigh its advantages. While it provides protection to shareholders and creditors, it can be a nuisance by restraining directors’ activities and preventing companies from changing their activities with mutual agreement.

- The purpose of the doctrine has been undermined since the object clause can now be easily altered by passing a special resolution of the shareholders.

Articles of Association

The articles of association outline the rules and regulations for managing a company's internal affairs. They define the duties, rights, and powers of the governing body and the procedures for conducting the company's business. The articles accept the memorandum of association as the foundation and detail how the company's internal regulations can be changed.Importance and Contents:

- The articles regulate the domestic management of the company and create rights and obligations between members and the company.

- Section 5 of the Companies Act, 2013 specifies the contents and model of articles of association, including regulations for management and provisions for entrenchment.

- Companies can include additional matters in their articles as needed for management.

Key Differences Between Memorandum and Articles of Association:

- Objectives: The memorandum defines the company's objectives, while the articles outline the rules for internal management.

- Relationship: The memorandum establishes the company's relationship with the outside world, whereas the articles govern the relationship between the company and its members.

- Alteration: The memorandum can only be altered under specific circumstances, often requiring permission from authorities. In contrast, the articles can be changed by passing a special resolution.

- Ultra Vires: Acts beyond the memorandum's scope are void and cannot be ratified, while acts beyond the articles can be ratified by a special resolution, provided they don't violate the memorandum.

Doctrine of Indoor Management

- Doctrine of Constructive Notice: Section 399 of the Companies Act, 2013 allows anyone to inspect documents kept by the Registrar, such as the certificate of incorporation, through electronic means by paying a prescribed fee. The memorandum and articles of association of a company, once registered with the Registrar of Companies, become public documents available for inspection by anyone for a nominal fee. This section grants the right of inspection to all, making it the responsibility of individuals dealing with a company to ensure their contracts conform to these documents. Whether a person reads the documents or not, it is presumed that they are aware of their contents, which is known as constructive notice. Constructive notice means that: (i) a person is presumed to have knowledge of the contents of the documents, regardless of whether they read them or not, and (ii) everyone dealing with the company has constructive notice of the memorandum, articles, and other related documents required to be registered. Therefore, if someone enters into a contract that exceeds the powers of the company as defined in the memorandum or the authority of directors as per the memorandum or articles, they cannot claim any rights under the contract against the company.

- Doctrine of Indoor Management: The Doctrine of Indoor Management is an exception to the doctrine of constructive notice. While constructive notice assumes that outsiders are aware of a company's internal affairs, the doctrine of indoor management protects outsiders dealing with a company. It allows outsiders to assume that all internal formalities have been followed when an act is authorized by the articles or memorandum. This principle was established in the case of The Royal British Bank vs. Turquand.

- Facts of the Case: In the case of The Royal British Bank vs. Turquand, Mr. Turquand, the official manager of the insolvent Cameron’s Coalbrook Steam, Coal and Swansea and Loughor Railway Company, sued the company on behalf of the bank. The company had issued a bond for £2,000 to the Royal British Bank, securing the company’s drawings on its current account. The bond was under the company’s seal, signed by two directors and the secretary. However, the company argued that its articles of association limited the directors' borrowing power to an amount specified by a company resolution. The resolution had been passed but did not specify the borrowing limit. The court held that the bond was valid, allowing the Royal British Bank to enforce its terms. The court ruled that the bank was deemed to be aware of the borrowing limit set by the resolutions, but it could not be expected to know the specific ordinary resolutions since they were not registrable. The bond was upheld because there was no requirement for the bank to investigate the company’s internal procedures, illustrating the indoor management rule.

Exceptions to the Doctrine of Indoor Management: The doctrine of Indoor Management, also known as the Turquand Rule, has its limitations and is not applicable in certain cases:

- Actual or Constructive Knowledge of Irregularity: The rule does not protect individuals dealing with a company who have actual or constructive knowledge of an irregularity. For example, in the case of Howard vs. Patent Ivory Manufacturing Co., directors could not defend the issuance of debentures to themselves because they should have known that the general meeting's assent was required, which had not been obtained. Similarly, in Morris v Kansseen, a director could not defend a share allotment to himself as he participated in the meeting that made the allotment, and his appointment as a director was also invalid.

- Suspicion of Irregularity: The doctrine does not reward individuals who behave negligently. If a person dealing with a company is put on inquiry due to an unusual transaction or a matter outside the ordinary course of business, it is their duty to make the necessary inquiry. The protection of the Turquand Rule is not available when the circumstances surrounding the contract are suspicious and invite scrutiny. For instance, in the case of Anand Bihari Lal vs. Dinshaw & Co., where the plaintiff accepted a transfer of a company’s property from its accountant without a power of attorney, the transfer was held void because the plaintiff could not assume the accountant had the authority to effect such a transfer. Likewise, in Haughton & Co. v. Nothard, Lowe & Wills Ltd., where a person holding directorship in two companies agreed to use one company's funds to pay off the debt of another, the court ruled that the unusual nature of the transaction put the plaintiff on inquiry regarding the authority of the parties making the contract.

- Forgery: The doctrine of indoor management applies to irregularities that may affect a transaction, but it does not extend to forgery, which is considered a nullity. Forgery may exclude the application of the Turquand Rule. A clear illustration of this is found in the case of Ruben v Great Fingall Consolidated. In this case, the plaintiff was a transferee of a share certificate issued under the seal of the defendant’s company. The company’s secretary affixed the seal and forged the signatures of the two directors on the certificate. The plaintiff argued that the genuineness of the signatures was a matter of internal management, and the company should be estopped from denying the authenticity of the document. However, it was held that the rule did not cover such a complete forgery, and the company was not bound by the forged document.

|

32 videos|185 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on The Companies Act, 2013 Chapter Notes - Business Laws for CA Foundation

| 1. What is the meaning of a company under the Companies Act, 2013? |  |

| 2. What is the Corporate Veil Theory? |  |

| 3. What are the different classes of companies under the Companies Act, 2013? |  |

| 4. What is the process for the registration or incorporation of a company? |  |

| 5. What is the significance of the Memorandum of Association and Articles of Association? |  |