Government Budget and the Economy Chapter Notes | Economics Class 12 - Commerce PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Government Budget: Meaning and Components |

|

| Role of the Budget in National Policy |

|

| Balanced, Surplus, and Deficit Budget |

|

| Fiscal Policy: Government's Role in Economic Stability |

|

Government Budget: Meaning and Components

- The Indian Constitution (Article 112) mandates the government to present an Annual Financial Statement before Parliament. This statement, covering estimated receipts and expenditures, forms the core of the government budget for each financial year (April 1 – March 31).

While the budget outlines financial plans for a single year, its effects extend into future years. To track finances efficiently, the government maintains two separate accounts:

Revenue Account (Revenue Budget): Records income and expenditure for the current financial year.

Capital Account (Capital Budget): Deals with government assets and liabilities.

Understanding these accounts is key to grasping the objectives and impact of the government budget on the economy.

Objectives of the Government Budget

The government plays a vital role in enhancing public welfare by actively intervening in the economy. This intervention is carried out through three key functions:

1. Allocation Function of the Government Budget

Certain goods and services, known as public goods, cannot be efficiently provided by private markets. Examples include national defense, roads, and government administration.

To understand the need for government intervention, it is important to differentiate between:

Private Goods (e.g., clothes, cars, food): Their consumption is rivalrous (one person's use reduces availability for others) and excludable (people who do not pay can be denied access).

Public Goods (e.g., clean air, street lighting): They are non-rivalrous (one person's use does not limit others) and non-excludable (everyone can benefit, even without paying).

Since individuals may not voluntarily pay for public goods (free-rider problem), the government must finance them through taxation. Public goods can be:

Publicly Provided: Funded through the budget but may be produced by either the government or private entities.

Publicly Produced: Directly manufactured or managed by the government.

2. Redistribution Function of the Government Budget

The government redistributes income to create a fairer society. National income is divided between:

Private Income (earnings of firms and households).

Public Income (revenue collected by the government).

Households receive personal income, and their actual spending capacity is termed personal disposable income. The government influences this through:

Taxes: Reducing disposable income for wealthier groups.

Transfers (Subsidies, Welfare Schemes): Increasing income for the less privileged.

By adjusting taxation and public spending, the government ensures a more equitable income distribution.

3. Stabilization Function of the Government Budget

Economic stability requires the government to regulate demand and control economic fluctuations:

In periods of low demand: Unemployment rises, as businesses do not have enough consumers. The government steps in by increasing spending or reducing taxes to boost demand.

In periods of excessive demand: High employment levels can lead to inflation. The government may impose restrictive measures (higher taxes, reduced spending) to slow down demand.

This stabilization function ensures a balanced economy, preventing extreme fluctuations in employment and prices.

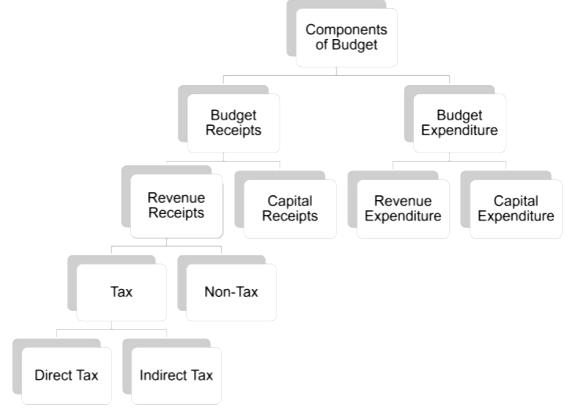

Classification of Receipts

Government receipts are classified into Revenue Receipts and Capital Receipts, based on their impact on government liabilities and financial assets.

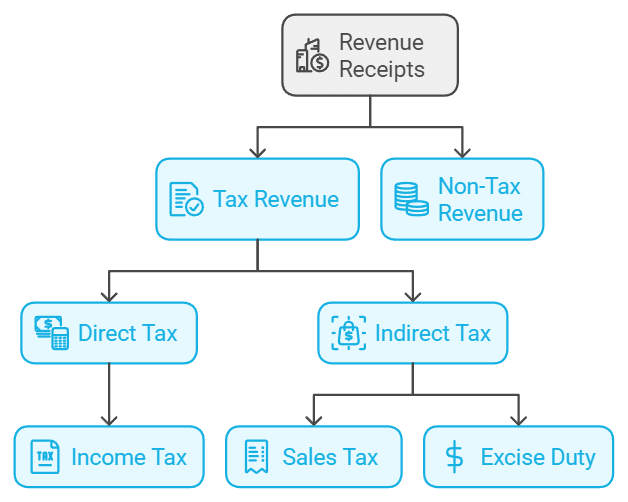

1. Revenue Receipts

Revenue receipts do not create liabilities for the government and are considered non-redeemable. They are further categorized into tax revenue and non-tax revenue.

Tax Revenue

Tax revenue is collected through direct and indirect taxes:

Direct Taxes: Levied on individuals and businesses, such as income tax (on individuals) and corporation tax (on firms).

Indirect Taxes: Levied on goods and services, including:

Excise duty: Tax on goods produced within the country.

Customs duty: Tax on imports and exports.

Service tax (earlier applicable, now replaced by GST).

Some direct taxes, like wealth tax, gift tax, and estate duty, were minor sources of revenue and were eventually abolished.

The government uses progressive taxation (higher income = higher tax rate) to achieve income redistribution. Indirect taxes vary based on the type of goods:

Necessities: Exempted or taxed at low rates.

Comforts and semi-luxuries: Moderately taxed.

Luxuries, tobacco, and petroleum products: Heavily taxed.

Non-Tax Revenue

Non-tax revenue includes:

Interest receipts from loans given by the government.

Dividends and profits from government investments.

Fees and service charges for government services.

Grants-in-aid from foreign countries and international organizations.

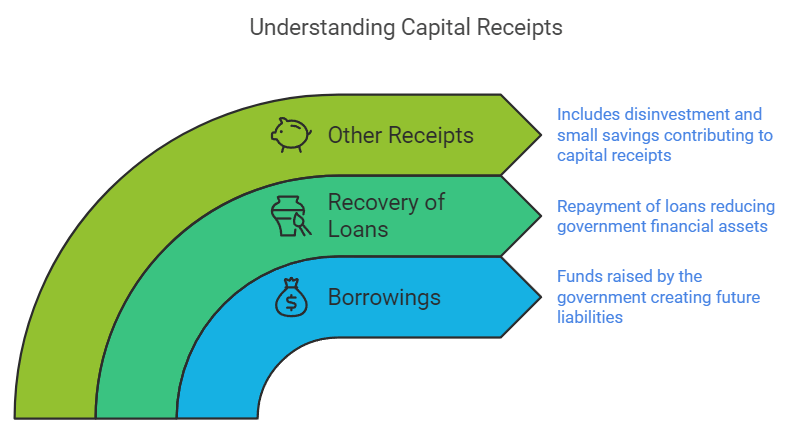

2. Capital Receipts

Capital receipts include money received by the government that creates liabilities or reduces financial assets. These receipts fall into two categories:

Debt-Creating Receipts

Loans: Borrowed from external agencies (like foreign governments or the World Bank) or internal sources (such as bonds and securities). These must be repaid with interest.

Non-Debt Creating Receipts

Disinvestment: Selling government-owned shares in Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs), reducing financial assets but not creating liabilities.

Capital receipts help the government meet its financial needs but can impact future financial stability due to repayment obligations and loss of revenue-generating assets.

Sources of Capital Receipt

- Borrowings: This includes funds raised by the govt through loans from the public, Reserve Bank of India, etc. It is a capital receipt for the government as it creates liability for the government as the funds raised need to be repaid by the government in future.

- Recovery of loan: The Repayment of loans by the state and union territory to the government falls under this category. Recovery of a loan is a capital receipt as it reduces the financial asset of the government.

- Other Receipts: This includes capital receipts from Disinvestment and Small Savings.

Classification of Expenditure

Government expenditure is classified into Revenue Expenditure and Capital Expenditure, based on whether it creates assets or liabilities.

1. Revenue Expenditure

Revenue expenditure refers to expenditures that do not create physical or financial assets for the government. It covers:

Normal functioning of government departments and services.

Interest payments on loans taken by the government.

Grants given to state governments and other entities, even if used for asset creation.

Plan and Non-Plan Expenditure (Earlier Classification)

Budget documents earlier categorized revenue expenditure into:

Plan Revenue Expenditure: Related to Five-Year Plans and assistance to State and Union Territory Plans.

Non-Plan Revenue Expenditure: Included general, economic, and social services, such as:

Interest payments on loans (largest component).

Defence expenditure (essential for national security).

Subsidies (on food, fertilizers, exports, and loans).

Salaries and pensions of government employees.

Though plan and non-plan expenditure classification was used earlier, since 2017, this distinction has been discontinued, and expenditure is now categorized into revenue and capital expenditure.

2. Capital Expenditure

Capital expenditure refers to government spending that creates physical or financial assets or reduces liabilities. It includes:

Acquisition of assets (land, buildings, machinery, equipment).

Investment in shares of public sector undertakings (PSUs).

Loans and advances to states, union territories, and other entities.

Similar to revenue expenditure, earlier, capital expenditure was divided into:

Plan Capital Expenditure: Related to development projects under the Five-Year Plans.

Non-Plan Capital Expenditure: Covered social, economic, and general services provided by the government.

Role of the Budget in National Policy

The government budget is not just a statement of income and expenditure but also a policy tool that influences economic development. Since Independence, budgets have been linked to national economic planning, shaping fiscal policies and growth strategies.

Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003 (FRBMA)

To ensure fiscal discipline, the government is required to present three key policy statements along with the budget:

Medium-term Fiscal Policy Statement: Sets three-year targets for fiscal indicators and assesses whether revenue expenditure is sustainable.

Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement: Explains the government's fiscal priorities, current policies, and any deviations from earlier plans.

Macroeconomic Framework Statement: Analyses the growth rate, fiscal balance, and external economic conditions.

These measures ensure transparency and accountability in government financial management.

Balanced, Surplus, and Deficit Budget

The government plans its budget based on how much money it collects and spends.

Balanced Budget: When the government’s income (taxes and other revenues) matches its spending, the budget is balanced. If expenses increase, the government must collect more taxes to maintain this balance.

Surplus Budget: If the government collects more money than it spends, it has a surplus budget. This means extra funds are available, which can be used for future needs or to reduce debt.

Deficit Budget: When the government spends more than it earns, it leads to a budget deficit. This is common, as governments often need to invest in infrastructure, welfare programs, and development projects.

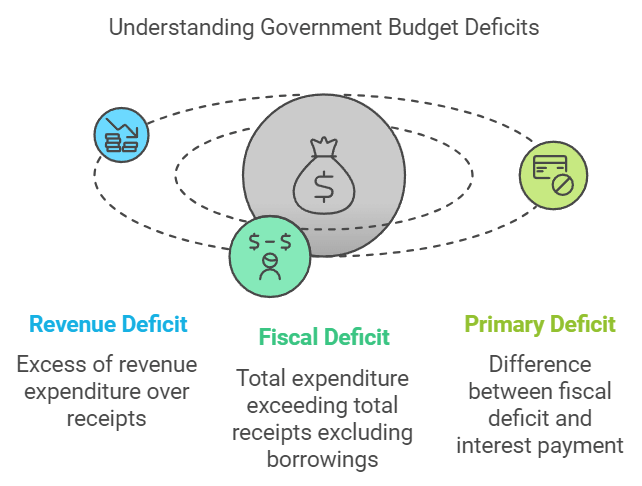

Measures of Government Deficit

When a government spends more than its earnings, it creates a budget deficit. There are different ways to measure this:

1. Revenue Deficit

Formula:

Revenue Deficit = Revenue Expenditure- Revenue ReceiptsThis happens when the government’s day-to-day expenses exceed its income from taxes and other sources.

A revenue deficit means the government is borrowing to cover routine expenses, which can increase debt and reduce funds for future growth.

2. Fiscal Deficit

Formula:

Fiscal Deficit = Total Expenditure − (Revenue Receipts + Non-Debt Capital Receipts)It represents the total borrowing needed to cover expenses.

If a large portion of the fiscal deficit comes from revenue deficit, it means the government is borrowing not for investment but to cover daily expenses, which can be harmful in the long run.

3. Primary Deficit

Formula:

Primary Deficit = Fiscal Deficit- Interest PaymentsIt shows how much of the deficit is due to current spending rather than past loans.

If the primary deficit is high, it means the government is overspending even without considering past debt obligations.

These deficit measures help assess the financial health of the economy and guide policies to maintain stability.

Fiscal Policy: Government's Role in Economic Stability

John Maynard Keynes, in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, emphasized the importance of fiscal policy in stabilizing the economy. Governments use spending and taxation to influence output and employment.

How the Government Affects the Economy

Government Spending (G): When the government spends on goods and services, it increases aggregate demand, leading to higher production and employment.

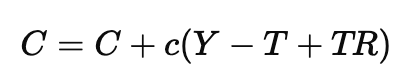

Taxes (T) and Transfers (TR):

Taxes reduce disposable income, which lowers consumption.

Transfers (such as pensions, unemployment benefits) increase disposable income, boosting spending.

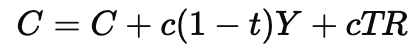

The new formula for consumption (C) is:

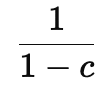

where Y is income and c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

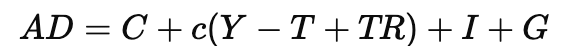

This modifies the aggregate demand (AD) equation to:

where I is investment and G is government spending.

Impact of Government Expenditure on Income

If G > T, the government runs a deficit budget (spending more than revenue).

If G < T, it creates a surplus budget.

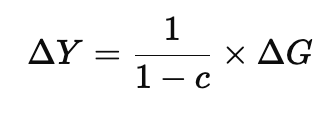

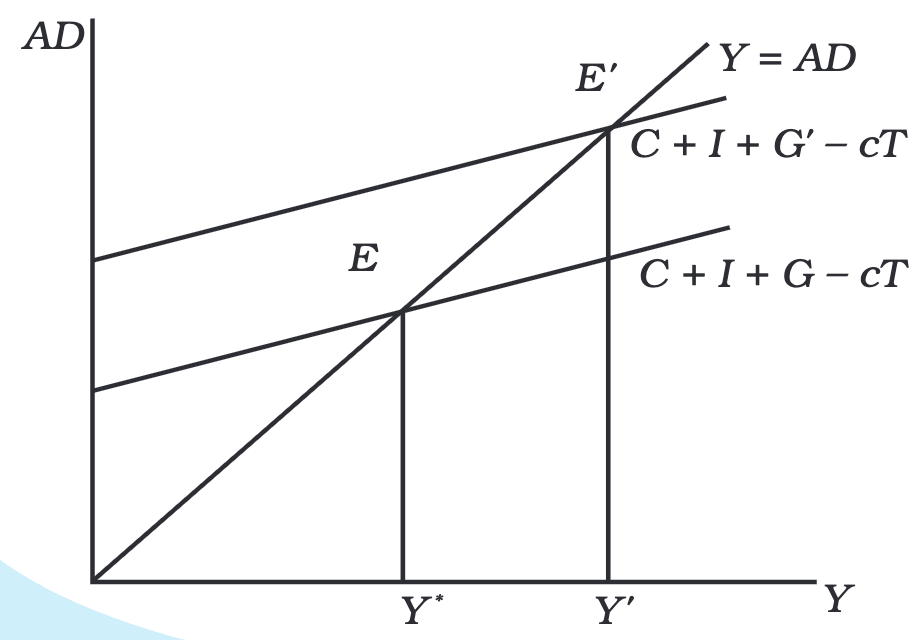

Increasing G while keeping T constant shifts the aggregate demand curve upward, leading to higher output (Y’).

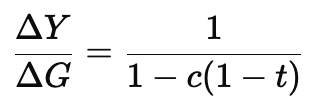

Using the multiplier effect, the increase in income () due to government spending is:

This means that a rise in government spending leads to a more significant increase in total income due to the multiplier effect.

Changes in Taxes

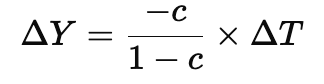

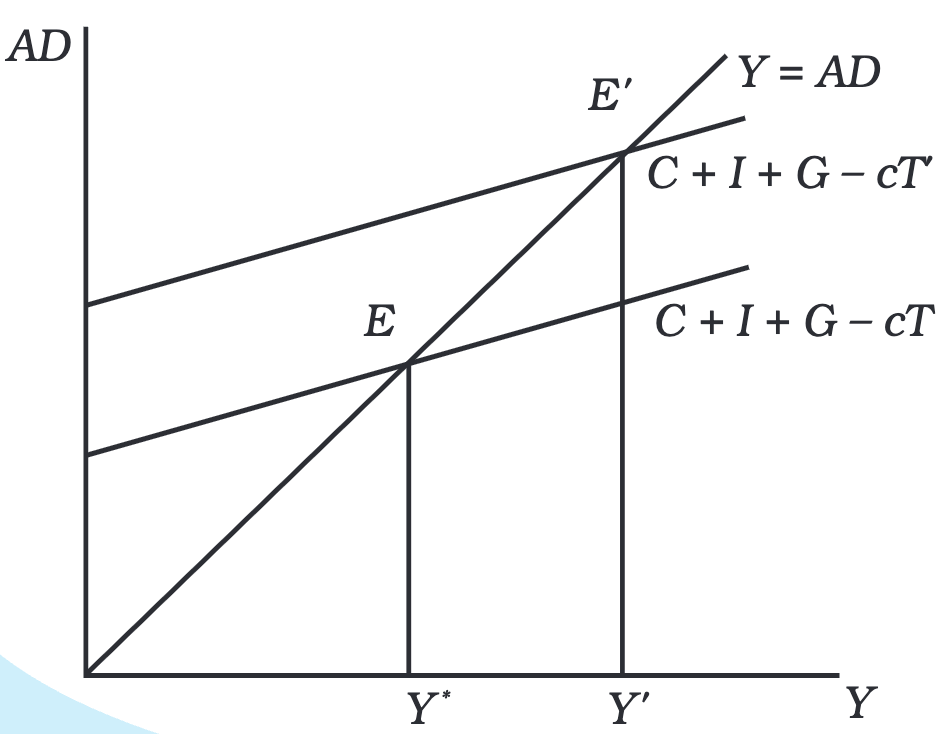

When the government reduces taxes, people have more disposable income (Y - T), leading to an increase in consumption (C). This raises aggregate expenditure (AE), shifting the demand curve upward.

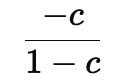

Tax Multiplier

The impact of tax changes on income is measured using the tax multiplier, calculated as:

where c is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

Since a tax cut increases spending and output, the tax multiplier is negative.

Comparing Government Spending and Tax Multipliers

Government Spending Multiplier:

It directly increases total spending.

Tax Multiplier:

It indirectly affects spending by first increasing disposable income.

Since taxes influence spending indirectly, the tax multiplier is smaller than the government spending multiplier.

Example

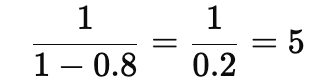

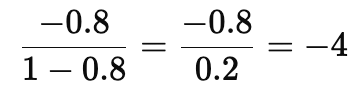

If MPC = 0.8:

- Government spending multiplier =

So, an increase in government spending by 100 leads to an income increase of 500.

Tax multiplier =

So, a tax cut of 100 increases income by 400.

Government spending has a larger impact on income than tax cuts.

While both tools help boost economic activity, direct government spending stimulates growth more effectively.

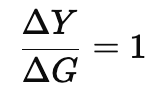

Balanced Budget Multiplier

The tax multiplier is always one less in absolute value than the government spending multiplier. This means that if the government increases spending (G) and taxes (T) by the same amount, the net effect on income (Y) is equal to the increase in G.

Mathematically, the balanced budget multiplier is:

This implies that if the government spends ₹100 more and increases taxes by ₹100, the national income increases by exactly ₹100.

Why is the Balanced Budget Multiplier Equal to 1?

When the government increases spending (G), it directly raises income and further increases it through the multiplier effect.

However, the increase in taxes (T) reduces consumption, which lowers income.

Since G = T, the net increase in income remains equal to G.

For example, if:

G increases by ₹100, income increases by ₹500 (using a multiplier of 5).

T increases by ₹100, reducing income by ₹400.

Net increase in income = ₹500 - ₹400 = ₹100.

Thus, income increases by the exact amount of G with no extra consumption-driven spending.

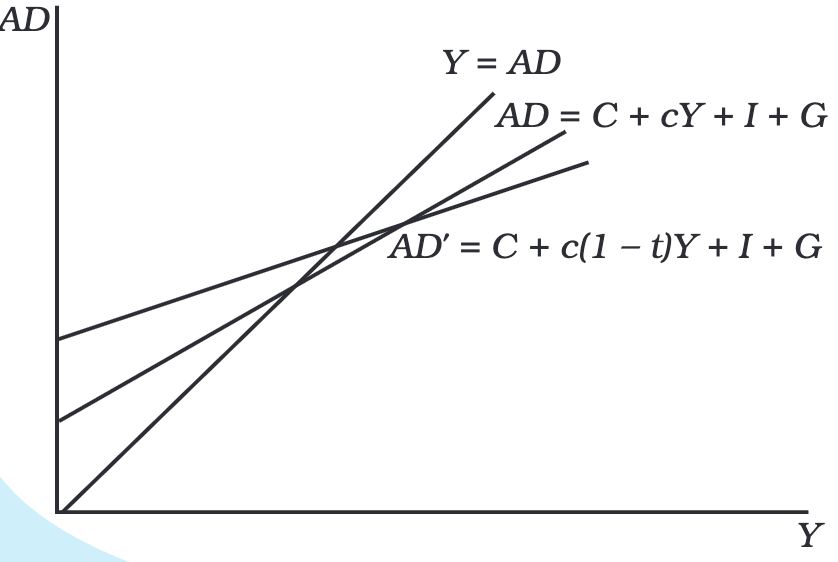

Proportional Taxes and the Multiplier

A more realistic assumption is that the government collects taxes as a percentage (t) of income (Y), meaning T = tY. This affects consumption and aggregate demand:

Since a portion of income is automatically taxed, people consume less at every income level. This makes the aggregate demand curve flatter because increases in income lead to smaller increases in consumption.

The new multiplier with proportional taxes is:

Since (1 - t) < 1, the multiplier is smaller than in the lump-sum tax case.

Proportional taxes make the AD schedule flatter

Proportional taxes make the AD schedule flatter

Example

If MPC = 0.8 and tax rate t = 0.25:

Effective MPC = 0.8 × (1 - 0.25) = 0.6

Government spending multiplier = 1 / (1 - 0.6) = 2.5

If G increases by ₹100, income increases by ₹250 instead of ₹500 (when lump-sum taxes were used).

This shows that proportional taxes reduce the overall impact of government spending on income.

|

64 videos|308 docs|51 tests

|

FAQs on Government Budget and the Economy Chapter Notes - Economics Class 12 - Commerce

| 1. What is a government budget and why is it important for the economy? |  |

| 2. What are the main components of a government budget? |  |

| 3. How does a government budget impact public services? |  |

| 4. What is a budget deficit and what are its consequences? |  |

| 5. How do government budgets influence economic policies? |  |