CAT Practice Test - 8 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Practice Test - 8

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The stylization underlying all existing writing systems is at the root of orthography, which literally means "drawing right" As long as writing was based on drawing a recognizable picture, its exact shape could vary. Once written symbols became a matter of convention, there was only a single way to spell them properly, or a single "orthography".

A second factor that drew writing away from pictography was the problem of drawing pictures of abstract ideas. No picture could possibly depict freedom, master and slave, victory, or god. Frequently, an association of ideas did the trick. In cuneiform writing, a divinity was a star; the profile of a face with the mouth touching a bowl meant a ration of food. Unfortunately, clever as they were, these conventions only meant anything to the trained eye --the direct connection from picture to meaning was lost.

Another trick consisted of exploiting the similarity between certain sounds to draw what were essentially visual puns. This is known by historians as the rebus principle. It involves the use of a pictogram to represent a syllabic sound. This procedure converts pictograms into phonograms. This kind of transcription of meaning progressively gave way to writing sounds. With the rebus principle, the Sumerians and the Egyptians gradually created an array of symbols that could transcribe any speech sound in their languages.

The Egyptians and the Sumerians thus came very close to the alphabetic principle, but neither managed to extract this gem from their overblown writing systems. The rebus strategy would have allowed them to write a word or sentence with a compact set of phonetic signs, but they continued to supplement them with a vast array of pictograms. This unfortunate mixture of two systems, one primarily based on sound, the other on meaning, created considerable ambiguity.

With the wisdom of hindsight, it is clear that the scribes could have simplified their system vastly by choosing to stick to speech sounds alone. Unfortunately, cultural evolution suffers from inertia and does not make rational decisions. Consequently, both the Egyptians and the Sumerians simply followed the natural slope of increasing complexity. Cuneiform notation added "determinative" ideograms to clarify the concept of the accompanying signs. Each marked the semantic categories of words: city, man, stone, wood, God, and so on. For instance, the character for "plow:' accompanied by the determinative "wood;' meant the agricultural tool. Determinatives also helped specify the meanings of words written in syllabic notation -a useful trick since any given syllable often corresponded to several homophone words (much like "one" and "won").

Why do mixed writing systems appear to constitute such a stable attractor for societies throughout the world? The reason for this probably lies at the crossroads of multiple constraints: the way our memory is structured, how language is organized, and the availability of certain brain connections. Our memory is poorly equipped for purely pictographic or logographic script, where each word has its own symbol. The mere notation of sounds would be equally unsatisfactory. Reading would be comparable to decoding a rebus-it wood bee two in knee fish hunt. A mixed system using fragments of both sound and meaning appears to be the best solution.

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

Q. In the fifth paragraph, the word ‘determinative' can be replaced by

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The stylization underlying all existing writing systems is at the root of orthography, which literally means "drawing right" As long as writing was based on drawing a recognizable picture, its exact shape could vary. Once written symbols became a matter of convention, there was only a single way to spell them properly, or a single "orthography".

A second factor that drew writing away from pictography was the problem of drawing pictures of abstract ideas. No picture could possibly depict freedom, master and slave, victory, or god. Frequently, an association of ideas did the trick. In cuneiform writing, a divinity was a star; the profile of a face with the mouth touching a bowl meant a ration of food. Unfortunately, clever as they were, these conventions only meant anything to the trained eye --the direct connection from picture to meaning was lost.

Another trick consisted of exploiting the similarity between certain sounds to draw what were essentially visual puns. This is known by historians as the rebus principle. It involves the use of a pictogram to represent a syllabic sound. This procedure converts pictograms into phonograms. This kind of transcription of meaning progressively gave way to writing sounds. With the rebus principle, the Sumerians and the Egyptians gradually created an array of symbols that could transcribe any speech sound in their languages.

The Egyptians and the Sumerians thus came very close to the alphabetic principle, but neither managed to extract this gem from their overblown writing systems. The rebus strategy would have allowed them to write a word or sentence with a compact set of phonetic signs, but they continued to supplement them with a vast array of pictograms. This unfortunate mixture of two systems, one primarily based on sound, the other on meaning, created considerable ambiguity.

With the wisdom of hindsight, it is clear that the scribes could have simplified their system vastly by choosing to stick to speech sounds alone. Unfortunately, cultural evolution suffers from inertia and does not make rational decisions. Consequently, both the Egyptians and the Sumerians simply followed the natural slope of increasing complexity. Cuneiform notation added "determinative" ideograms to clarify the concept of the accompanying signs. Each marked the semantic categories of words: city, man, stone, wood, God, and so on. For instance, the character for "plow:' accompanied by the determinative "wood;' meant the agricultural tool. Determinatives also helped specify the meanings of words written in syllabic notation -a useful trick since any given syllable often corresponded to several homophone words (much like "one" and "won").

Why do mixed writing systems appear to constitute such a stable attractor for societies throughout the world? The reason for this probably lies at the crossroads of multiple constraints: the way our memory is structured, how language is organized, and the availability of certain brain connections. Our memory is poorly equipped for purely pictographic or logographic script, where each word has its own symbol. The mere notation of sounds would be equally unsatisfactory. Reading would be comparable to decoding a rebus-it wood bee two in knee fish hunt. A mixed system using fragments of both sound and meaning appears to be the best solution.

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

Q. What is the purpose of using this line in the passage - it wood bee two in knee fish hunt.'?

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The stylization underlying all existing writing systems is at the root of orthography, which literally means "drawing right" As long as writing was based on drawing a recognizable picture, its exact shape could vary. Once written symbols became a matter of convention, there was only a single way to spell them properly, or a single "orthography".

A second factor that drew writing away from pictography was the problem of drawing pictures of abstract ideas. No picture could possibly depict freedom, master and slave, victory, or god. Frequently, an association of ideas did the trick. In cuneiform writing, a divinity was a star; the profile of a face with the mouth touching a bowl meant a ration of food. Unfortunately, clever as they were, these conventions only meant anything to the trained eye --the direct connection from picture to meaning was lost.

Another trick consisted of exploiting the similarity between certain sounds to draw what were essentially visual puns. This is known by historians as the rebus principle. It involves the use of a pictogram to represent a syllabic sound. This procedure converts pictograms into phonograms. This kind of transcription of meaning progressively gave way to writing sounds. With the rebus principle, the Sumerians and the Egyptians gradually created an array of symbols that could transcribe any speech sound in their languages.

The Egyptians and the Sumerians thus came very close to the alphabetic principle, but neither managed to extract this gem from their overblown writing systems. The rebus strategy would have allowed them to write a word or sentence with a compact set of phonetic signs, but they continued to supplement them with a vast array of pictograms. This unfortunate mixture of two systems, one primarily based on sound, the other on meaning, created considerable ambiguity.

With the wisdom of hindsight, it is clear that the scribes could have simplified their system vastly by choosing to stick to speech sounds alone. Unfortunately, cultural evolution suffers from inertia and does not make rational decisions. Consequently, both the Egyptians and the Sumerians simply followed the natural slope of increasing complexity. Cuneiform notation added "determinative" ideograms to clarify the concept of the accompanying signs. Each marked the semantic categories of words: city, man, stone, wood, God, and so on. For instance, the character for "plow:' accompanied by the determinative "wood;' meant the agricultural tool. Determinatives also helped specify the meanings of words written in syllabic notation -a useful trick since any given syllable often corresponded to several homophone words (much like "one" and "won").

Why do mixed writing systems appear to constitute such a stable attractor for societies throughout the world? The reason for this probably lies at the crossroads of multiple constraints: the way our memory is structured, how language is organized, and the availability of certain brain connections. Our memory is poorly equipped for purely pictographic or logographic script, where each word has its own symbol. The mere notation of sounds would be equally unsatisfactory. Reading would be comparable to decoding a rebus-it wood bee two in knee fish hunt. A mixed system using fragments of both sound and meaning appears to be the best solution.

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

Q. From its inception in Mesopotamia, the "virus" of writing spread quickly to the surrounding cultures. The epidemic, however, remained confined, in all societies, to a small group of specialists. The complexity of this invention curbed its capacity to spread. Even in present-day China, scholars must learn several thousand signs. As recently as the 1950s, the rate of illiteracy in the adult Chinese population was close to 80 percent-before _________ and massive investment in education brought this figure down to about 10 percent.

Excerpted from ‘Reading in the Brain' by Stanislas Dehaene Page 184-193

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Why should we be concerned with symmetry? In the first place, symmetry is fascinating to the human mind, and everyone likes objects or patterns that are in some way symmetrical. It is an interesting fact that nature often exhibits certain kinds of symmetry in the objects we find in the world around us. Perhaps the most symmetrical object imaginable is a sphere, and nature is full of spheres—stars, planets, water droplets in clouds. The crystals found in rocks exhibit many different kinds of symmetry, the study of which tells us some important things about the structure of solids.

But our main concern here is not with the fact that the objects of nature are often symmetrical. Rather, we wish to examine some of the even more remarkable symmetries of the universe—the symmetries that exist in the basic laws themselves which govern the operation of the physical world.

First, what is symmetry? How can a physical law be “symmetrical”? The problem of defining symmetry is an interesting one and we have already noted that Weyl gave a good definition, the substance of which is that a thing is symmetrical if there is something we can do to it so that after we have done it, it looks the same as it did before. For example, a symmetrical vase is of such a kind that if we reflect or turn it, it will look the same as it did before. The question we wish to consider here is what we can do to physical phenomena, or to a physical situation in an experiment, and yet leave the result the same.

The first thing we might try to do, for example, is to translate the phenomenon in space. If we do an experiment in a certain region, and then build another apparatus at another place in space (or move the original one over) then, whatever went on in one apparatus, in a certain order in time, will occur in the same way if we have arranged the same condition, with all due attention to the restrictions that we mentioned before: that all of those features of the environment which make it not behave the same way have also been moved over.

In the same way, we also believe today that displacement in time will have no effect on physical laws. Another thing that we discussed in considerable detail was rotation in space: if we turn an apparatus at an angle it works just as well, provided we turn everything else that is relevant along with it. On a more advanced level we had another symmetry—the symmetry under uniform velocity in a straight line. That is to say—a rather remarkable effect—that if we have a piece of apparatus working a certain way and then take the same apparatus and put it in a car, and move the whole car, plus all the relevant surroundings, at a uniform velocity in a straight line, then so far as the phenomena inside the car are concerned there is no difference: all the laws of physics appear the same.

Excerpted from the Feynman Lecture on Physics, Vol I

Q. You would ask the author all the questions given below, except,

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Why should we be concerned with symmetry? In the first place, symmetry is fascinating to the human mind, and everyone likes objects or patterns that are in some way symmetrical. It is an interesting fact that nature often exhibits certain kinds of symmetry in the objects we find in the world around us. Perhaps the most symmetrical object imaginable is a sphere, and nature is full of spheres—stars, planets, water droplets in clouds. The crystals found in rocks exhibit many different kinds of symmetry, the study of which tells us some important things about the structure of solids.

But our main concern here is not with the fact that the objects of nature are often symmetrical. Rather, we wish to examine some of the even more remarkable symmetries of the universe—the symmetries that exist in the basic laws themselves which govern the operation of the physical world.

First, what is symmetry? How can a physical law be “symmetrical”? The problem of defining symmetry is an interesting one and we have already noted that Weyl gave a good definition, the substance of which is that a thing is symmetrical if there is something we can do to it so that after we have done it, it looks the same as it did before. For example, a symmetrical vase is of such a kind that if we reflect or turn it, it will look the same as it did before. The question we wish to consider here is what we can do to physical phenomena, or to a physical situation in an experiment, and yet leave the result the same.

The first thing we might try to do, for example, is to translate the phenomenon in space. If we do an experiment in a certain region, and then build another apparatus at another place in space (or move the original one over) then, whatever went on in one apparatus, in a certain order in time, will occur in the same way if we have arranged the same condition, with all due attention to the restrictions that we mentioned before: that all of those features of the environment which make it not behave the same way have also been moved over.

In the same way, we also believe today that displacement in time will have no effect on physical laws. Another thing that we discussed in considerable detail was rotation in space: if we turn an apparatus at an angle it works just as well, provided we turn everything else that is relevant along with it. On a more advanced level we had another symmetry—the symmetry under uniform velocity in a straight line. That is to say—a rather remarkable effect—that if we have a piece of apparatus working a certain way and then take the same apparatus and put it in a car, and move the whole car, plus all the relevant surroundings, at a uniform velocity in a straight line, then so far as the phenomena inside the car are concerned there is no difference: all the laws of physics appear the same.

Excerpted from the Feynman Lecture on Physics, Vol I

Q. What can you say about the laws of physics with reference to the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Why should we be concerned with symmetry? In the first place, symmetry is fascinating to the human mind, and everyone likes objects or patterns that are in some way symmetrical. It is an interesting fact that nature often exhibits certain kinds of symmetry in the objects we find in the world around us. Perhaps the most symmetrical object imaginable is a sphere, and nature is full of spheres—stars, planets, water droplets in clouds. The crystals found in rocks exhibit many different kinds of symmetry, the study of which tells us some important things about the structure of solids.

But our main concern here is not with the fact that the objects of nature are often symmetrical. Rather, we wish to examine some of the even more remarkable symmetries of the universe—the symmetries that exist in the basic laws themselves which govern the operation of the physical world.

First, what is symmetry? How can a physical law be “symmetrical”? The problem of defining symmetry is an interesting one and we have already noted that Weyl gave a good definition, the substance of which is that a thing is symmetrical if there is something we can do to it so that after we have done it, it looks the same as it did before. For example, a symmetrical vase is of such a kind that if we reflect or turn it, it will look the same as it did before. The question we wish to consider here is what we can do to physical phenomena, or to a physical situation in an experiment, and yet leave the result the same.

The first thing we might try to do, for example, is to translate the phenomenon in space. If we do an experiment in a certain region, and then build another apparatus at another place in space (or move the original one over) then, whatever went on in one apparatus, in a certain order in time, will occur in the same way if we have arranged the same condition, with all due attention to the restrictions that we mentioned before: that all of those features of the environment which make it not behave the same way have also been moved over.

In the same way, we also believe today that displacement in time will have no effect on physical laws. Another thing that we discussed in considerable detail was rotation in space: if we turn an apparatus at an angle it works just as well, provided we turn everything else that is relevant along with it. On a more advanced level we had another symmetry—the symmetry under uniform velocity in a straight line. That is to say—a rather remarkable effect—that if we have a piece of apparatus working a certain way and then take the same apparatus and put it in a car, and move the whole car, plus all the relevant surroundings, at a uniform velocity in a straight line, then so far as the phenomena inside the car are concerned there is no difference: all the laws of physics appear the same.

Excerpted from the Feynman Lecture on Physics, Vol I

Q. What is the tone of the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Workhouses have long assumed a central place in studies on the poor laws. While we know that the majority of relief claimants were actually given outdoor relief in money or in kind from the parish pay-table, welfare historians have shown that many individuals entered workhouses during moments of both short and long-term need. This dynamic has a long history. The Elizabethan poor laws permitted parishes to find accommodation for ‘poor impotent people’ in addition to the requirement to ‘set to work’ their poor. Some cities had obtained their own ‘Local Acts’ which contained specific legislation designed for the specific welfare needs of that locale. Central to these Acts was the workhouse. The first Local Act was passed in 1696 for the Civic Incorporation of Bristol.

Born in Staffordshire, Gilbert was a chief land agent to Lord Gower and a keen poor law reformer. Through his work, he developed an immense political, legal, commercial and industrial knowledge which enabled the Gower estate to become one of the most prosperous in England. Gilbert’s concern for the poor may have stemmed out of his role as agent, which had allowed him to take onboard the role of paymaster for a charity of naval officers’ widows. As Marshall noted, Gilbert thought old parish workhouses were ‘dens of horror’. Such workhouses were too uncomfortable for those who were in poverty due to no fault of their own and places where the young were susceptible to ‘Habits of Virtue and Vice’ learnt from ‘bad characters’. For the sake of both the poor and the rates, Gilbert thought that workhouses should be reformed to promote industrious behavior.

These ideas culminated in a new bill and the subsequent Act of 1782 which enabled parishes to provide a workhouse solely for the accommodation of the vulnerable. Although such residents were, as Gilbert put it, ‘not able to maintain themselves by their Labor’ outside of the workhouse they were still to ‘be employed in doing as much Work as they can’ within the workhouse. Work was therefore a part of everyday life within a Gilbert’s Act workhouse. The able-bodied were only to be offered temporary shelter and instead were to be found employment and provided with outdoor relief. Those who refused such work (the ‘idle’) were to endure ‘hard Labor in the Houses of Correction’.

How was such a workhouse to be established and managed? Gilbert wanted to allow parishes to unite together so that they could combine their resources and provide a well built and maintained workhouse. According to Steve King, Gilbert’s Act was the first real breach of the Old Poor Law principle ‘local problem - local treatment’. Yet, any ‘Parish, Town, or Township’ was also permitted to implement the law alone, and hence concerns over poverty did not always transcend parish boundaries. Gilbert’s Act workhouses were to be managed in a different way compared to the older parish workhouses. Gilbert believed that the poor laws had been ‘unhappily’ executed ‘through the misconduct of overseers’. Such officers, he claimed ‘gratify themselves and their Favorites, and to neglect the more deserving Objects’. This dim view of overseers was shared by many others at the time.

excerpted from 'Welfare of the vulnerable' by Samantha Shave

Q. What question would you like to ask the author after reading the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Workhouses have long assumed a central place in studies on the poor laws. While we know that the majority of relief claimants were actually given outdoor relief in money or in kind from the parish pay-table, welfare historians have shown that many individuals entered workhouses during moments of both short and long-term need. This dynamic has a long history. The Elizabethan poor laws permitted parishes to find accommodation for ‘poor impotent people’ in addition to the requirement to ‘set to work’ their poor. Some cities had obtained their own ‘Local Acts’ which contained specific legislation designed for the specific welfare needs of that locale. Central to these Acts was the workhouse. The first Local Act was passed in 1696 for the Civic Incorporation of Bristol.

Born in Staffordshire, Gilbert was a chief land agent to Lord Gower and a keen poor law reformer. Through his work, he developed an immense political, legal, commercial and industrial knowledge which enabled the Gower estate to become one of the most prosperous in England. Gilbert’s concern for the poor may have stemmed out of his role as agent, which had allowed him to take onboard the role of paymaster for a charity of naval officers’ widows. As Marshall noted, Gilbert thought old parish workhouses were ‘dens of horror’. Such workhouses were too uncomfortable for those who were in poverty due to no fault of their own and places where the young were susceptible to ‘Habits of Virtue and Vice’ learnt from ‘bad characters’. For the sake of both the poor and the rates, Gilbert thought that workhouses should be reformed to promote industrious behavior.

These ideas culminated in a new bill and the subsequent Act of 1782 which enabled parishes to provide a workhouse solely for the accommodation of the vulnerable. Although such residents were, as Gilbert put it, ‘not able to maintain themselves by their Labor’ outside of the workhouse they were still to ‘be employed in doing as much Work as they can’ within the workhouse. Work was therefore a part of everyday life within a Gilbert’s Act workhouse. The able-bodied were only to be offered temporary shelter and instead were to be found employment and provided with outdoor relief. Those who refused such work (the ‘idle’) were to endure ‘hard Labor in the Houses of Correction’.

How was such a workhouse to be established and managed? Gilbert wanted to allow parishes to unite together so that they could combine their resources and provide a well built and maintained workhouse. According to Steve King, Gilbert’s Act was the first real breach of the Old Poor Law principle ‘local problem - local treatment’. Yet, any ‘Parish, Town, or Township’ was also permitted to implement the law alone, and hence concerns over poverty did not always transcend parish boundaries. Gilbert’s Act workhouses were to be managed in a different way compared to the older parish workhouses. Gilbert believed that the poor laws had been ‘unhappily’ executed ‘through the misconduct of overseers’. Such officers, he claimed ‘gratify themselves and their Favorites, and to neglect the more deserving Objects’. This dim view of overseers was shared by many others at the time.

excerpted from 'Welfare of the vulnerable' by Samantha Shave

Q. What does the term ‘poor impotent people’ imply contextually?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Workhouses have long assumed a central place in studies on the poor laws. While we know that the majority of relief claimants were actually given outdoor relief in money or in kind from the parish pay-table, welfare historians have shown that many individuals entered workhouses during moments of both short and long-term need. This dynamic has a long history. The Elizabethan poor laws permitted parishes to find accommodation for ‘poor impotent people’ in addition to the requirement to ‘set to work’ their poor. Some cities had obtained their own ‘Local Acts’ which contained specific legislation designed for the specific welfare needs of that locale. Central to these Acts was the workhouse. The first Local Act was passed in 1696 for the Civic Incorporation of Bristol.

Born in Staffordshire, Gilbert was a chief land agent to Lord Gower and a keen poor law reformer. Through his work, he developed an immense political, legal, commercial and industrial knowledge which enabled the Gower estate to become one of the most prosperous in England. Gilbert’s concern for the poor may have stemmed out of his role as agent, which had allowed him to take onboard the role of paymaster for a charity of naval officers’ widows. As Marshall noted, Gilbert thought old parish workhouses were ‘dens of horror’. Such workhouses were too uncomfortable for those who were in poverty due to no fault of their own and places where the young were susceptible to ‘Habits of Virtue and Vice’ learnt from ‘bad characters’. For the sake of both the poor and the rates, Gilbert thought that workhouses should be reformed to promote industrious behavior.

These ideas culminated in a new bill and the subsequent Act of 1782 which enabled parishes to provide a workhouse solely for the accommodation of the vulnerable. Although such residents were, as Gilbert put it, ‘not able to maintain themselves by their Labor’ outside of the workhouse they were still to ‘be employed in doing as much Work as they can’ within the workhouse. Work was therefore a part of everyday life within a Gilbert’s Act workhouse. The able-bodied were only to be offered temporary shelter and instead were to be found employment and provided with outdoor relief. Those who refused such work (the ‘idle’) were to endure ‘hard Labor in the Houses of Correction’.

How was such a workhouse to be established and managed? Gilbert wanted to allow parishes to unite together so that they could combine their resources and provide a well built and maintained workhouse. According to Steve King, Gilbert’s Act was the first real breach of the Old Poor Law principle ‘local problem - local treatment’. Yet, any ‘Parish, Town, or Township’ was also permitted to implement the law alone, and hence concerns over poverty did not always transcend parish boundaries. Gilbert’s Act workhouses were to be managed in a different way compared to the older parish workhouses. Gilbert believed that the poor laws had been ‘unhappily’ executed ‘through the misconduct of overseers’. Such officers, he claimed ‘gratify themselves and their Favorites, and to neglect the more deserving Objects’. This dim view of overseers was shared by many others at the time.

excerpted from 'Welfare of the vulnerable' by Samantha Shave

Q. Which among the following is not true as per the passage?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Consider these recent headlines: “Want to be Happier? Be More Grateful,” “The Formula for Happiness: Gratitude Plays a Part,” “Teaching Gratitude, Bringing Happiness to Children,” and my personal favorite “Key to Happiness is Gratitude, and Men May be Locked Out.”

Buoyed by research findings from the field of positive psychology, the happiness industry is alive and flourishing in America. Each of these headlines includes the explicit assumption that gratitude should be part of any 12-step, 30-day, or 10-key program to develop happiness. But how does this bear on the question toward which this essay is directed? Is gratitude queen of the virtues? In modern times gratitude has become untethered from its moral moorings and collectively, we are worse off because of this. When the Roman philosopher Cicero stated that gratitude was the queen of the virtues, he most assuredly did not mean that gratitude was merely a stepping-stone toward personal happiness. Gratitude is a morally complex disposition, and reducing this virtue to a technique or strategy to improve one’s mood is to do it an injustice.

Even restricting gratitude to an inner feeling is insufficient. In the history of ideas, gratitude is considered an action (returning a favor) that is not only virtuous in and of itself, but valuable to society. To reciprocate is the right thing to do. “There is no duty more indispensable that that of returning a kindness” wrote Cicero in a book whose title translates “On Duties.” Cicero’s contemporary, Seneca, maintained that “He who receives a benefit with gratitude repays the first installment on his debt.” Neither believed that the emotion felt in a person returning a favor was particularly crucial. Conversely, across time, ingratitude has been treated as a serious vice, a greater vice than gratitude is a virtue. Ingratitude is the “essence of vileness,” wrote the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant while David Hume opined that ingratitude is “the most horrible and unnatural crime that a person is capable of committing.”

Gratitude does matter for happiness. As someone who for the past decade has contributed to the scientific literature on gratitude and well-being, I would certainly grant that. The tools and techniques of modern science have been brought to bear on understanding the nature of gratitude and why it is important for human flourishing more generally. From childhood to old age, accumulating evidence documents the wide array of psychological, physical, and relational benefits associated with gratitude. Yet I have come to the realization that by taking a “gratitude lite” approach we have cheapened gratitude. Gratitude is important not only because it helps people feel good, but also because it inspires them to do good. Gratitude heals, energizes, and transforms lives in a myriad of ways consistent with the notion that virtue is both its own reward and produces other rewards.

To give a flavor of these research findings, dispositional gratitude has been found to be positively associated qualities such as empathy, forgiveness, and the willingness to help others. For example, people who rated themselves as having a grateful disposition perceived themselves as having more prosocial characteristics, expressed by their empathetic behavior, and emotional support for friends within the last month. When people report feeling grateful, thankful, and appreciative in studies of daily experience, they also feel more loving, forgiving, joyful, and enthusiastic. Notably, the family, friends, partners and others that surround them consistently report that people who practice gratitude are viewed as more helpful, more outgoing, more optimistic, and more trustworthy. On a larger level, gratitude is the adhesive that binds members of society together. Gratitude is the “moral memory of mankind” wrote noted sociologist Georg Simmel.

Q. With reference to the passage, what does the author mean by a ‘gratitude-lite’ approach?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Consider these recent headlines: “Want to be Happier? Be More Grateful,” “The Formula for Happiness: Gratitude Plays a Part,” “Teaching Gratitude, Bringing Happiness to Children,” and my personal favorite “Key to Happiness is Gratitude, and Men May be Locked Out.”

Buoyed by research findings from the field of positive psychology, the happiness industry is alive and flourishing in America. Each of these headlines includes the explicit assumption that gratitude should be part of any 12-step, 30-day, or 10-key program to develop happiness. But how does this bear on the question toward which this essay is directed? Is gratitude queen of the virtues? In modern times gratitude has become untethered from its moral moorings and collectively, we are worse off because of this. When the Roman philosopher Cicero stated that gratitude was the queen of the virtues, he most assuredly did not mean that gratitude was merely a stepping-stone toward personal happiness. Gratitude is a morally complex disposition, and reducing this virtue to a technique or strategy to improve one’s mood is to do it an injustice.

Even restricting gratitude to an inner feeling is insufficient. In the history of ideas, gratitude is considered an action (returning a favor) that is not only virtuous in and of itself, but valuable to society. To reciprocate is the right thing to do. “There is no duty more indispensable that that of returning a kindness” wrote Cicero in a book whose title translates “On Duties.” Cicero’s contemporary, Seneca, maintained that “He who receives a benefit with gratitude repays the first installment on his debt.” Neither believed that the emotion felt in a person returning a favor was particularly crucial. Conversely, across time, ingratitude has been treated as a serious vice, a greater vice than gratitude is a virtue. Ingratitude is the “essence of vileness,” wrote the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant while David Hume opined that ingratitude is “the most horrible and unnatural crime that a person is capable of committing.”

Gratitude does matter for happiness. As someone who for the past decade has contributed to the scientific literature on gratitude and well-being, I would certainly grant that. The tools and techniques of modern science have been brought to bear on understanding the nature of gratitude and why it is important for human flourishing more generally. From childhood to old age, accumulating evidence documents the wide array of psychological, physical, and relational benefits associated with gratitude. Yet I have come to the realization that by taking a “gratitude lite” approach we have cheapened gratitude. Gratitude is important not only because it helps people feel good, but also because it inspires them to do good. Gratitude heals, energizes, and transforms lives in a myriad of ways consistent with the notion that virtue is both its own reward and produces other rewards.

To give a flavor of these research findings, dispositional gratitude has been found to be positively associated qualities such as empathy, forgiveness, and the willingness to help others. For example, people who rated themselves as having a grateful disposition perceived themselves as having more prosocial characteristics, expressed by their empathetic behavior, and emotional support for friends within the last month. When people report feeling grateful, thankful, and appreciative in studies of daily experience, they also feel more loving, forgiving, joyful, and enthusiastic. Notably, the family, friends, partners and others that surround them consistently report that people who practice gratitude are viewed as more helpful, more outgoing, more optimistic, and more trustworthy. On a larger level, gratitude is the adhesive that binds members of society together. Gratitude is the “moral memory of mankind” wrote noted sociologist Georg Simmel.

Q. The author of the passage will agree with the statement:

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Consider these recent headlines: “Want to be Happier? Be More Grateful,” “The Formula for Happiness: Gratitude Plays a Part,” “Teaching Gratitude, Bringing Happiness to Children,” and my personal favorite “Key to Happiness is Gratitude, and Men May be Locked Out.”

Buoyed by research findings from the field of positive psychology, the happiness industry is alive and flourishing in America. Each of these headlines includes the explicit assumption that gratitude should be part of any 12-step, 30-day, or 10-key program to develop happiness. But how does this bear on the question toward which this essay is directed? Is gratitude queen of the virtues? In modern times gratitude has become untethered from its moral moorings and collectively, we are worse off because of this. When the Roman philosopher Cicero stated that gratitude was the queen of the virtues, he most assuredly did not mean that gratitude was merely a stepping-stone toward personal happiness. Gratitude is a morally complex disposition, and reducing this virtue to a technique or strategy to improve one’s mood is to do it an injustice.

Even restricting gratitude to an inner feeling is insufficient. In the history of ideas, gratitude is considered an action (returning a favor) that is not only virtuous in and of itself, but valuable to society. To reciprocate is the right thing to do. “There is no duty more indispensable that that of returning a kindness” wrote Cicero in a book whose title translates “On Duties.” Cicero’s contemporary, Seneca, maintained that “He who receives a benefit with gratitude repays the first installment on his debt.” Neither believed that the emotion felt in a person returning a favor was particularly crucial. Conversely, across time, ingratitude has been treated as a serious vice, a greater vice than gratitude is a virtue. Ingratitude is the “essence of vileness,” wrote the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant while David Hume opined that ingratitude is “the most horrible and unnatural crime that a person is capable of committing.”

Gratitude does matter for happiness. As someone who for the past decade has contributed to the scientific literature on gratitude and well-being, I would certainly grant that. The tools and techniques of modern science have been brought to bear on understanding the nature of gratitude and why it is important for human flourishing more generally. From childhood to old age, accumulating evidence documents the wide array of psychological, physical, and relational benefits associated with gratitude. Yet I have come to the realization that by taking a “gratitude lite” approach we have cheapened gratitude. Gratitude is important not only because it helps people feel good, but also because it inspires them to do good. Gratitude heals, energizes, and transforms lives in a myriad of ways consistent with the notion that virtue is both its own reward and produces other rewards.

To give a flavor of these research findings, dispositional gratitude has been found to be positively associated qualities such as empathy, forgiveness, and the willingness to help others. For example, people who rated themselves as having a grateful disposition perceived themselves as having more prosocial characteristics, expressed by their empathetic behavior, and emotional support for friends within the last month. When people report feeling grateful, thankful, and appreciative in studies of daily experience, they also feel more loving, forgiving, joyful, and enthusiastic. Notably, the family, friends, partners and others that surround them consistently report that people who practice gratitude are viewed as more helpful, more outgoing, more optimistic, and more trustworthy. On a larger level, gratitude is the adhesive that binds members of society together. Gratitude is the “moral memory of mankind” wrote noted sociologist Georg Simmel.

Q. As per the context of the passage, identify the correct statements:

I. According to the author, the happiness industry has over-used the concept of gratitude for its own benefit.

II. According to Cicero, gratitude induces a feeling of debt in the benefactor.

III. The rewards obtained from gratitude cannot be limited to one sphere of human life.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

When you visit your doctor you enter a world of queues and disjointed processes. Why? Because your doctor and health care planner think about health care from the standpoint of organization charts, functional expertise, and "efficiency." Each of the centers of expertise in the health care system —the specialist physician, the single-purpose diagnostic tool, the centralized laboratory—is extremely expensive. Therefore, efficiency demands that it be completely utilized.

To get full utilization, it's necessary to route you around from specialist to machine to laboratory and to over schedule the specialists, machines, and labs to make sure they are always fully occupied. Elaborate computerized information systems are needed to make sure you find your place in the right line and to get your records from central storage to the point of diagnosis or treatment.

How would things work if the medical system embraced lean thinking? First, the patient would be placed in the foreground, with time and comfort included as key performance measures of the system. These can only be addressed by flowing the patient through the system.

Next, the medical system would rethink its departmental structure and reorganize much of its expertise into multi skilled teams. The idea would be very simple: When the patient enters the system, via a multi skilled, co-located team, she or he receives steady attention and treatment until the problem is solved.

To do this, the skills of nurses and doctors would need to be broadened so that a smaller team of more broadly skilled people can solve most patient problems. At the same time, the tools of medicine—machines, labs, and record-keeping units—would need to be rethought and "right-sized" so that they are smaller, more flexible, and faster, with a full complement of tools dedicated to every treatment team.

Finally, the "patient" would need to be actively involved in the process and up-skilled—made a member of the team—so that many problems can be solved through prevention or addressed from home without need to physically visit the medical team, and so that visits can be better predicted. Over time, it will surely be possible to transfer some of the equipment to the home as well, through teleconferencing, remote sensing, and even a home laboratory, the same way most of us now have a complete complement of office equipment in our home offices.

What would happen if lean thinking was introduced as a fundamental principle of health care? The time and steps needed to solve a problem should fall dramatically. The quality of care should improve because less information would be lost in handoffs to the next specialist, fewer mistakes would be made, less elaborate information tracking and scheduling systems would be needed, and less backtracking and rework would be required. The cost of each "cure" and of the total system could fall substantially.

Excerpted from page numbers 289-290 of ‘Lean Thinking’ by Womack and Jones

Q. What is the skill enhancement required in healthcare professionals in order to make the transition to lean?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

When you visit your doctor you enter a world of queues and disjointed processes. Why? Because your doctor and health care planner think about health care from the standpoint of organization charts, functional expertise, and "efficiency." Each of the centers of expertise in the health care system —the specialist physician, the single-purpose diagnostic tool, the centralized laboratory—is extremely expensive. Therefore, efficiency demands that it be completely utilized.

To get full utilization, it's necessary to route you around from specialist to machine to laboratory and to over schedule the specialists, machines, and labs to make sure they are always fully occupied. Elaborate computerized information systems are needed to make sure you find your place in the right line and to get your records from central storage to the point of diagnosis or treatment.

How would things work if the medical system embraced lean thinking? First, the patient would be placed in the foreground, with time and comfort included as key performance measures of the system. These can only be addressed by flowing the patient through the system.

Next, the medical system would rethink its departmental structure and reorganize much of its expertise into multi skilled teams. The idea would be very simple: When the patient enters the system, via a multi skilled, co-located team, she or he receives steady attention and treatment until the problem is solved.

To do this, the skills of nurses and doctors would need to be broadened so that a smaller team of more broadly skilled people can solve most patient problems. At the same time, the tools of medicine—machines, labs, and record-keeping units—would need to be rethought and "right-sized" so that they are smaller, more flexible, and faster, with a full complement of tools dedicated to every treatment team.

Finally, the "patient" would need to be actively involved in the process and up-skilled—made a member of the team—so that many problems can be solved through prevention or addressed from home without need to physically visit the medical team, and so that visits can be better predicted. Over time, it will surely be possible to transfer some of the equipment to the home as well, through teleconferencing, remote sensing, and even a home laboratory, the same way most of us now have a complete complement of office equipment in our home offices.

What would happen if lean thinking was introduced as a fundamental principle of health care? The time and steps needed to solve a problem should fall dramatically. The quality of care should improve because less information would be lost in handoffs to the next specialist, fewer mistakes would be made, less elaborate information tracking and scheduling systems would be needed, and less backtracking and rework would be required. The cost of each "cure" and of the total system could fall substantially.

Excerpted from page numbers 289-290 of ‘Lean Thinking’ by Womack and Jones

Q. What philosophy is implied when the article advises that the patient should also be part of the healthcare team?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

When you visit your doctor you enter a world of queues and disjointed processes. Why? Because your doctor and health care planner think about health care from the standpoint of organization charts, functional expertise, and "efficiency." Each of the centers of expertise in the health care system —the specialist physician, the single-purpose diagnostic tool, the centralized laboratory—is extremely expensive. Therefore, efficiency demands that it be completely utilized.

To get full utilization, it's necessary to route you around from specialist to machine to laboratory and to over schedule the specialists, machines, and labs to make sure they are always fully occupied. Elaborate computerized information systems are needed to make sure you find your place in the right line and to get your records from central storage to the point of diagnosis or treatment.

How would things work if the medical system embraced lean thinking? First, the patient would be placed in the foreground, with time and comfort included as key performance measures of the system. These can only be addressed by flowing the patient through the system.

Next, the medical system would rethink its departmental structure and reorganize much of its expertise into multi skilled teams. The idea would be very simple: When the patient enters the system, via a multi skilled, co-located team, she or he receives steady attention and treatment until the problem is solved.

To do this, the skills of nurses and doctors would need to be broadened so that a smaller team of more broadly skilled people can solve most patient problems. At the same time, the tools of medicine—machines, labs, and record-keeping units—would need to be rethought and "right-sized" so that they are smaller, more flexible, and faster, with a full complement of tools dedicated to every treatment team.

Finally, the "patient" would need to be actively involved in the process and up-skilled—made a member of the team—so that many problems can be solved through prevention or addressed from home without need to physically visit the medical team, and so that visits can be better predicted. Over time, it will surely be possible to transfer some of the equipment to the home as well, through teleconferencing, remote sensing, and even a home laboratory, the same way most of us now have a complete complement of office equipment in our home offices.

What would happen if lean thinking was introduced as a fundamental principle of health care? The time and steps needed to solve a problem should fall dramatically. The quality of care should improve because less information would be lost in handoffs to the next specialist, fewer mistakes would be made, less elaborate information tracking and scheduling systems would be needed, and less backtracking and rework would be required. The cost of each "cure" and of the total system could fall substantially.

Excerpted from page numbers 289-290 of ‘Lean Thinking’ by Womack and Jones

Q. What can be inferred to be the central philosophy of lean thinking?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

When you visit your doctor you enter a world of queues and disjointed processes. Why? Because your doctor and health care planner think about health care from the standpoint of organization charts, functional expertise, and "efficiency." Each of the centers of expertise in the health care system —the specialist physician, the single-purpose diagnostic tool, the centralized laboratory—is extremely expensive. Therefore, efficiency demands that it be completely utilized.

To get full utilization, it's necessary to route you around from specialist to machine to laboratory and to over schedule the specialists, machines, and labs to make sure they are always fully occupied. Elaborate computerized information systems are needed to make sure you find your place in the right line and to get your records from central storage to the point of diagnosis or treatment.

How would things work if the medical system embraced lean thinking? First, the patient would be placed in the foreground, with time and comfort included as key performance measures of the system. These can only be addressed by flowing the patient through the system.

Next, the medical system would rethink its departmental structure and reorganize much of its expertise into multi skilled teams. The idea would be very simple: When the patient enters the system, via a multi skilled, co-located team, she or he receives steady attention and treatment until the problem is solved.

To do this, the skills of nurses and doctors would need to be broadened so that a smaller team of more broadly skilled people can solve most patient problems. At the same time, the tools of medicine—machines, labs, and record-keeping units—would need to be rethought and "right-sized" so that they are smaller, more flexible, and faster, with a full complement of tools dedicated to every treatment team.

Finally, the "patient" would need to be actively involved in the process and up-skilled—made a member of the team—so that many problems can be solved through prevention or addressed from home without need to physically visit the medical team, and so that visits can be better predicted. Over time, it will surely be possible to transfer some of the equipment to the home as well, through teleconferencing, remote sensing, and even a home laboratory, the same way most of us now have a complete complement of office equipment in our home offices.

What would happen if lean thinking was introduced as a fundamental principle of health care? The time and steps needed to solve a problem should fall dramatically. The quality of care should improve because less information would be lost in handoffs to the next specialist, fewer mistakes would be made, less elaborate information tracking and scheduling systems would be needed, and less backtracking and rework would be required. The cost of each "cure" and of the total system could fall substantially.

Excerpted from page numbers 289-290 of ‘Lean Thinking’ by Womack and Jones

Q. Based on a reading of this article, what prediction can we make about the technology of the homes of the future?

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Last semester I tried to create a college classroom that was a technological desert. I wanted the space to be a respite from the demands and distractions of smartphones, tablets, and computers. So I banned the use of technology " because asking students to be professional digital citizens had not worked.

Simply requesting that students put away their phones was an exercise in futility. Adding a line in the syllabus that there would be grade penalties for unprofessional use of technology brought about no change in their habits of swiping and clicking. They meant no disrespect. Technology pulled at them " and pulls at us " creating a sense of urgency that few can ignore. I get it. This is not a college-student problem (I've been to faculty meetings). It's a human problem.

DIRECTIONS for the question:

The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4, and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentence and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. The Trump administration’s health-care reform bill now in the Senate, and the version that passed the House this May, will force some women to pay more again.

2. Specifically, American women of child-bearing age paid somewhere between 52% and 69% more in out-of-pocket healthcare costs than men.

3. Despite the incontrovertible fact that men are biologically just as responsible as women for a pregnancy happening, before the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, women in the US paid more for health care and insurance because they are the ones who can get pregnant.

4. Specifically, it strips out hundreds of billions of dollars from Medicaid, the insurance for the poor, which now covers over 50% of all births in many US states, and allows states to opt out of covering “essential” healthcare that includes maternity and newborn care.

5. The Senate bill was crafted behind closed doors, by 13 men and no women. A search of the language used in the 142-page draft document shows that womanhood and motherhood are, quite literally, also omitted from most of the bill itself.

DIRECTIONS for the question:

The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4, and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentence and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. Tellingly, as the city’s resources shrank and conquests grew, Rome’s agricultural deity, Mars, became the god of war.

2. Rome’s imperialism emerged in part in response to nutrient losses, the center expanding to support its vast needs with timber, food, and other resources elsewhere.

3. In Imperial Rome service people took wastes away from public spaces and the toilets of the wealthy and piled them outside the city.

4. Agriculture and tree-felling drained soils of nutrients and led to erosion, and the landscape became drier and more arid, with less fertile cropland.

5. There is an old Roman saying, pecunia non olet: “money doesn’t stink.”

DIRECTIONS for the question:

Five sentences related to a topic are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out. Choose its number as your answer and key it in.

1. Neruda's family and supporters have been divided over whether the case should be closed or whether researchers should continue carrying out tests.

2. Neruda's chauffeur claimed Pinochet's agents took advantage of the poet's illness to inject poison into his stomach as he lay in hospital.

3. Luna also said that tests indicated that death from prostrate cancer was not likely at the moment when Neruda died.

4. Spanish forensic specialist Aurelio Luna from the University of Murcia told journalists that his team discovered something that could possibly be laboratory-cultivated bacteria.

5. We cannot confirm if the nature of Pablo Neruda's death was natural or violent.

DIRECTIONS for the question:

The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4, and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentence and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. To cope with its chronic water shortages, India employs electric groundwater pumps, diesel-powered water tankers and coal-fed power plants. If the country increasingly relies on these energy-intensive short-term fixes, the whole planet's climate will bear the consequences.

2. What India does with its water will be a test of whether that combination is possible.

3. If a country fails to keep up with the water needs of its growing cities, those cities will be unable to sustain the robust economic growth that has become a magnet for global investment.

4. Without sensible water policies, political agitation — like the recent controversies over Coca-Cola's use of groundwater in rural communities in southern and western India — will become more frequent and river-sharing negotiations with India's neighbors Pakistan and Bangladesh more tense.

5. India is under enormous pressure to develop its economic potential while also protecting its environment — something few, if any, countries have accomplished.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Identify the most appropriate summary for the paragraph.

Uber fits neatly into the mythology of the tech industry, which portrays itself as surfing one of the waves of "creative destruction" through which capitalism periodically renews itself. In this narrative, industrial progress involves a good deal of destruction in order to make way for new, creative, wealth-creating industries. The abolition of old timers such as licensed taxi cabs, travel agents and bookshops etc is merely the collateral damage of an essentially benign process " regrettable but necessary casualties of innovation. You don't have to be much of a sceptic to spot that this is self-serving cant. Far from being a radical innovation, Uber is a classic example of something as old as the internet itself, namely our old friend 'disintermediation'. The idea is to find a business in which the need of buyers to find sellers (and vice versa) has traditionally been handled by an intermediary, and then use networking technology to eliminate said middle man. It happened a very long time ago to travel agents and bookshops. Now it's happening to taxi firms. If this is technological innovation, then it's a pretty low-IQ manifestation of it.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Identify the most appropriate summary for the paragraph.

The advent of cooking enabled humans to eat more kinds of food, to devote less time to eating, and to make do with smaller teeth and shorter intestines. Some scholars believe there is a direct link between the advent of cooking, the shortening of the human intestinal track, and the growth of the human brain. Since long intestines and large brains are both massive energy consumers, it’s hard to have both.

DIRECTIONS for the question:

The five sentences (labelled 1,2,3,4, and 5) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentence and key in this sequence of five numbers as your answer.

1. The first people any rational society locks up are the most dangerous criminals, such as murderers and rapists.

2. The more people a country imprisons, the less dangerous each additional prisoner is likely to be.

3. At some point, the costs of incarceration start to outweigh the benefits: Prisons are expensive—cells must be built, guards hired, prisoners fed. The inmate, while confined, is unlikely to work, support his family or pay tax.

4. Money spent on prisons cannot be spent on other things that might reduce crime more, such as hiring extra police or improving pre-school in rough neighborhoods.

5. And—crucially—locking up minor offenders can make them more dangerous, since they learn felonious habits from the hard cases they meet inside.

DIRECTIONS for the question:

Four sentences related to a topic are given below. Three of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out. Choose its number as your answer and key it in.

1. What do some well-meaning shareholders and I want from the Infosys board?

2. No other company that has demonstrated a CAGR of 53.9% in market capitalization over twenty one years in the history of corporate India.

3. We just do not want the board to drive this institution to death through serious governance deficits in our own life time.

4. Not money, not position for our children and not power.

DIRECTIONS for the question: Read the information given below and answer the question that follows.

Teams from seven states – Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal – are participating in the national basketball championship. After the inauguration ceremony, the reporter from 11 Sports spoke to nine players – Akshay Kumar, Anil Thakur, David D’Souza, Jayesh Patel, Rahul Jha, Rajeev Sinha, Ramesh Nayudu, Sachdev Sharma and Subhash Divyundu – from these seven teams. Additional information about the interviews is as follows.

- Each player interviewed wore a jersey with a unique number.

- David D’Souza with jersey number 31 plays for Andhra Pradesh and is also known as a 3-pointer.

- Rajeev Sinha with jersey number 23 is the eldest player and Subhash Divyundu is the heaviest player.

- Sachdev Sharma has jersey number 30, while Jayesh Patel has jersey number 40.

- Rahul Jha is one of the dunkers and he is from West Bengal.

- The player from UP and one player from Andhra Pradesh have single digit jersey numbers.

- Both the players with jersey numbers 40 and 34 play for Gujrat.

- Rahul Jha was interviewed after Ramesh Nayudu, but was not the last player to be interviewed.

- Both the players from Andhra Pradesh were interviewed one after the other and they were followed by both players from Gujrat.

- The players from Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal were interviewed one after the other in that order.

- The player with jersey number 23 plays for Bihar.

- The heaviest player has jersey number 34.

- Ramesh Nayudu is a passer for Andhra Pradesh.

- Jersey numbers 2 and 3 were the only single digit jersey numbers.

- The player from Maharashtra was interviewed 7th.

Q. If David D’Souza was the first to be interviewed, who could not be interviewed 2nd?

DIRECTIONS for the question:

Read the information given below and answer the question that follows.

Teams from seven states – Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal – are participating in the national basketball championship. After the inauguration ceremony, the reporter from 11 Sports spoke to nine players – Akshay Kumar, Anil Thakur, David D’Souza, Jayesh Patel, Rahul Jha, Rajeev Sinha, Ramesh Nayudu, Sachdev Sharma and Subhash Divyundu – from these seven teams. Additional information about the interviews is as follows.

- Each player interviewed wore a jersey with a unique number.

- David D’Souza with jersey number 31 plays for Andhra Pradesh and is also known as a 3-pointer.

- Rajeev Sinha with jersey number 23 is the eldest player and Subhash Divyundu is the heaviest player.

- Sachdev Sharma has jersey number 30, while Jayesh Patel has jersey number 40.

- Rahul Jha is one of the dunkers and he is from West Bengal.

- The player from UP and one player from Andhra Pradesh have single digit jersey numbers.

- Both the players with jersey numbers 40 and 34 play for Gujrat.

- Rahul Jha was interviewed after Ramesh Nayudu, but was not the last player to be interviewed.

- Both the players from Andhra Pradesh were interviewed one after the other and they were followed by both players from Gujrat.

- The players from Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal were interviewed one after the other in that order.

- The player with jersey number 23 plays for Bihar.

- The heaviest player has jersey number 34.

- Ramesh Nayudu is a passer for Andhra Pradesh.

- Jersey numbers 2 and 3 were the only single digit jersey numbers.

- The player from Maharashtra was interviewed 7th.

Q. If Anil Thakur, Akshay Kumar and Sachdev Sharma were players who got interviewed in order, then who will not be wearing Jersey number 2?

DIRECTIONS for the question:

Read the information given below and answer the question that follows.

Teams from seven states – Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal – are participating in the national basketball championship. After the inauguration ceremony, the reporter from 11 Sports spoke to nine players – Akshay Kumar, Anil Thakur, David D’Souza, Jayesh Patel, Rahul Jha, Rajeev Sinha, Ramesh Nayudu, Sachdev Sharma and Subhash Divyundu – from these seven teams. Additional information about the interviews is as follows.

- Each player interviewed wore a jersey with a unique number.

- David D’Souza with jersey number 31 plays for Andhra Pradesh and is also known as a 3-pointer.

- Rajeev Sinha with jersey number 23 is the eldest player and Subhash Divyundu is the heaviest player.

- Sachdev Sharma has jersey number 30, while Jayesh Patel has jersey number 40.

- Rahul Jha is one of the dunkers and he is from West Bengal.

- The player from UP and one player from Andhra Pradesh have single digit jersey numbers.

- Both the players with jersey numbers 40 and 34 play for Gujrat.

- Rahul Jha was interviewed after Ramesh Nayudu, but was not the last player to be interviewed.

- Both the players from Andhra Pradesh were interviewed one after the other and they were followed by both players from Gujrat.

- The players from Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal were interviewed one after the other in that order.

- The player with jersey number 23 plays for Bihar.

- The heaviest player has jersey number 34.

- Ramesh Nayudu is a passer for Andhra Pradesh.

- Jersey numbers 2 and 3 were the only single digit jersey numbers.

- The player from Maharashtra was interviewed 7th.

Q. Referring to the previous two questions, which of the following may be the correct order of the interviewees?

DIRECTIONS for the question:

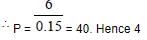

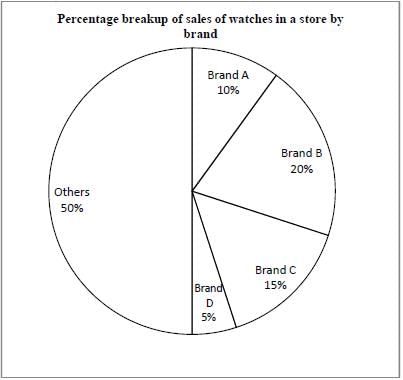

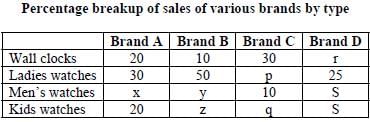

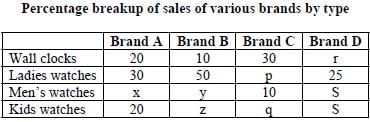

Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

Overall, brands A, B, C, and D's men's watches constitute 10 percent of all watches; their ladies watches constitute 20.25 percent of all watches, and kids Watches constitute 10.5 percent of all-watches.

Q. p = ?(in numerical value)

DIRECTIONS for the question:

Analyse the graph/s given below and answer the question that follows.

Overall, brands A, B, C, and D's men's watches constitute 10 percent of all watches; their ladies watches constitute 20.25 percent of all watches, and kids Watches constitute 10.5 percent of all-watches.

Q. z = ?(in numerical value)