CAT Verbal Mock Test - 2 - CAT MCQ

25 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Verbal Mock Test - 2

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

There is no better illustration to the life cycle of a civilization than The Course of Empire, a series of paintings by Thomas Cole that hang in the gallery of the New York Historical Society. Cole beautifully captured a theory to which most people remain in thrall to this day: the theory of cycles of civilization.

Each of the five imagined scenes depicts the mouth of a great river beneath a rocky outcrop. In the first, The Savage State, a lush wilderness is populated by a handful of hunter-gatherers eking out a primitive existence at the break of a stormy dawn. Imagine history from Columbus’ discovery of America in 1492 on through four more centuries as they savagely expanded across the continent. The second picture, ‘The Arcadian or Pastoral State,’ is of an agrarian idyll: the inhabitants have cleared the trees, planted fields, and built an elegant Greek temple.

The third and largest of the paintings is ‘The Consummation of Empire.’ Now, the landscape is covered by a magnificent marble entrepôt, and the contented farmer-philosophers of the previous tableau have been replaced by a throng of opulently clad merchants, proconsuls and citizen-consumers. It is midday in the life cycle.

Then comes ‘The Destruction of Empire,’ the fourth stage in Ferguson’s grand drama about the life-cycle of all empires. In ‘Destruction’ the city is ablaze, its citizens fleeing an invading horde that rapes and pillages beneath a brooding evening sky. Finally, the moon rises over the fifth painting, ‘Desolation,’ says Ferguson. There is not a living soul to be seen, only a few decaying columns and colonnades overgrown by briars and ivy.

Conceived in the mid-1830s, Cole’s pentaptych, a five-piece work of art, has a clear message: all civilizations, no matter how magnificent, are condemned to decline and fall. The implicit suggestion was that the young American republic of Cole’s age would do better to stick to its bucolic first principles and resist the temptations of commerce, conquest and colonization. For centuries, historians, political theorists, anthropologists and the public at large have tended to think about the rise and fall of civilizations in such cyclical and gradual terms…

More recently, it is the anthropologist Jared Diamond who has captured the public imagination with a grand theory of rise and fall. His book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, is cyclical history for the Green Age: tales of societies, from 17th century Easter Island to 21st century China, that risked, or now risk, destroying themselves by abusing their natural environments. Diamond quotes John Lloyd Stevens, the American explorer and amateur archaeologist who discovered the eerily dead Mayan cities of Mexico: ‘Here were the remains of a cultivated, polished, and peculiar people, who had passed through all the stages incident to the rise and fall of nations, reached their golden age, and perished.’ According to Diamond, the Maya fell into a classic Malthusian trap as their population grew larger than their fragile and inefficient agricultural system could support. More people meant more cultivation, but that means deforestation, erosion, drought and soil exhaustion. The result was civil war over dwindling resources and, finally, collapse.

Q. The Mayans were mentioned in the last para of the passage to signify that

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

There is no better illustration to the life cycle of a civilization than The Course of Empire, a series of paintings by Thomas Cole that hang in the gallery of the New York Historical Society. Cole beautifully captured a theory to which most people remain in thrall to this day: the theory of cycles of civilization.

Each of the five imagined scenes depicts the mouth of a great river beneath a rocky outcrop. In the first, The Savage State, a lush wilderness is populated by a handful of hunter-gatherers eking out a primitive existence at the break of a stormy dawn. Imagine history from Columbus’ discovery of America in 1492 on through four more centuries as they savagely expanded across the continent. The second picture, ‘The Arcadian or Pastoral State,’ is of an agrarian idyll: the inhabitants have cleared the trees, planted fields, and built an elegant Greek temple.

The third and largest of the paintings is ‘The Consummation of Empire.’ Now, the landscape is covered by a magnificent marble entrepôt, and the contented farmer-philosophers of the previous tableau have been replaced by a throng of opulently clad merchants, proconsuls and citizen-consumers. It is midday in the life cycle.

Then comes ‘The Destruction of Empire,’ the fourth stage in Ferguson’s grand drama about the life-cycle of all empires. In ‘Destruction’ the city is ablaze, its citizens fleeing an invading horde that rapes and pillages beneath a brooding evening sky. Finally, the moon rises over the fifth painting, ‘Desolation,’ says Ferguson. There is not a living soul to be seen, only a few decaying columns and colonnades overgrown by briars and ivy.

Conceived in the mid-1830s, Cole’s pentaptych, a five-piece work of art, has a clear message: all civilizations, no matter how magnificent, are condemned to decline and fall. The implicit suggestion was that the young American republic of Cole’s age would do better to stick to its bucolic first principles and resist the temptations of commerce, conquest and colonization. For centuries, historians, political theorists, anthropologists and the public at large have tended to think about the rise and fall of civilizations in such cyclical and gradual terms…

More recently, it is the anthropologist Jared Diamond who has captured the public imagination with a grand theory of rise and fall. His book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, is cyclical history for the Green Age: tales of societies, from 17th century Easter Island to 21st century China, that risked, or now risk, destroying themselves by abusing their natural environments. Diamond quotes John Lloyd Stevens, the American explorer and amateur archaeologist who discovered the eerily dead Mayan cities of Mexico: ‘Here were the remains of a cultivated, polished, and peculiar people, who had passed through all the stages incident to the rise and fall of nations, reached their golden age, and perished.’ According to Diamond, the Maya fell into a classic Malthusian trap as their population grew larger than their fragile and inefficient agricultural system could support. More people meant more cultivation, but that means deforestation, erosion, drought and soil exhaustion. The result was civil war over dwindling resources and, finally, collapse.

Q. Thomas Cole’s purpose in painting his pentaptych seems to be to highlight

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

There is no better illustration to the life cycle of a civilization than The Course of Empire, a series of paintings by Thomas Cole that hang in the gallery of the New York Historical Society. Cole beautifully captured a theory to which most people remain in thrall to this day: the theory of cycles of civilization.

Each of the five imagined scenes depicts the mouth of a great river beneath a rocky outcrop. In the first, The Savage State, a lush wilderness is populated by a handful of hunter-gatherers eking out a primitive existence at the break of a stormy dawn. Imagine history from Columbus’ discovery of America in 1492 on through four more centuries as they savagely expanded across the continent. The second picture, ‘The Arcadian or Pastoral State,’ is of an agrarian idyll: the inhabitants have cleared the trees, planted fields, and built an elegant Greek temple.

The third and largest of the paintings is ‘The Consummation of Empire.’ Now, the landscape is covered by a magnificent marble entrepôt, and the contented farmer-philosophers of the previous tableau have been replaced by a throng of opulently clad merchants, proconsuls and citizen-consumers. It is midday in the life cycle.

Then comes ‘The Destruction of Empire,’ the fourth stage in Ferguson’s grand drama about the life-cycle of all empires. In ‘Destruction’ the city is ablaze, its citizens fleeing an invading horde that rapes and pillages beneath a brooding evening sky. Finally, the moon rises over the fifth painting, ‘Desolation,’ says Ferguson. There is not a living soul to be seen, only a few decaying columns and colonnades overgrown by briars and ivy.

Conceived in the mid-1830s, Cole’s pentaptych, a five-piece work of art, has a clear message: all civilizations, no matter how magnificent, are condemned to decline and fall. The implicit suggestion was that the young American republic of Cole’s age would do better to stick to its bucolic first principles and resist the temptations of commerce, conquest and colonization. For centuries, historians, political theorists, anthropologists and the public at large have tended to think about the rise and fall of civilizations in such cyclical and gradual terms…

More recently, it is the anthropologist Jared Diamond who has captured the public imagination with a grand theory of rise and fall. His book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, is cyclical history for the Green Age: tales of societies, from 17th century Easter Island to 21st century China, that risked, or now risk, destroying themselves by abusing their natural environments. Diamond quotes John Lloyd Stevens, the American explorer and amateur archaeologist who discovered the eerily dead Mayan cities of Mexico: ‘Here were the remains of a cultivated, polished, and peculiar people, who had passed through all the stages incident to the rise and fall of nations, reached their golden age, and perished.’ According to Diamond, the Maya fell into a classic Malthusian trap as their population grew larger than their fragile and inefficient agricultural system could support. More people meant more cultivation, but that means deforestation, erosion, drought and soil exhaustion. The result was civil war over dwindling resources and, finally, collapse.

Q. Which of the following needs to be true to validate the last statement of the passage: ‘The result was civil war over dwindling resources and, finally, collapse’?

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The origins of the people of the Indus Valley civilization has prompted a long-running argument that has lasted for more than five decades.

Some scholars have suggested that they were originally migrants from upland plateaux to the west. Others have maintained the civilization was made up of indigenous local groups, while some have said it was a mixture of both, and part of a network of different communities in the region. Experts have also debated whether the civilization succumbed to a traumatic invasion by so-called “Aryans” whose chariots they were unable to resist, or in fact peaceably assimilated a series of waves of migration over many decades or centuries.

A new research will provide definitive answers, at least for the population of Rakhigarhi. It is a key site in the Indus Valley civilization which ruled a more than 1 million sq km swath of the Asian subcontinent during the bronze age and was as advanced and powerful as its better known contemporary counterparts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. “There is already evidence of intermarriage and mixing through trade and so forth for a long time and the DNA will tell us for sure,” said Vasant Shinde, an Indian archaeologist leading current excavations at Rakhigarhi.

Shinde’s conclusions will be published in the new year. They are based on DNA sequences derived from four skeletons excavated eight months ago and checked against DNA data from tens of thousands of people from all across the subcontinent, central Asia and Iran.

The conclusions from the new research on the skeletal DNA sample are likely to be controversial in a region riven by religious, ethnic and nationalist tensions. Hostile neighbours India and Pakistan have fought three wars since winning their independence from the British in 1947, and have long squabbled over the true centre of the Indus civilization, which straddles the border between the countries. Shinde said Rakhigarhi might have been a bigger city than either Mohenjodaro or Harappa, two sites in Pakistan previously considered the centre of the Indus civilization. Some in India will also be keen to claim any new research supports their belief that the Rig Veda, an ancient text sacred to Hindus compiled shortly after the demise of the Indus Valley civilization, is reliable as an historical record.

The question of links between today’s inhabitants of the area and those who lived, farmed, and died millennia ago has also prompted fierce argument. There are other mysteries too. The Indus Valley civilization flourished for three thousand years before disappearing suddenly around 1500 BC. Theories range from the drying up of local rivers to an epidemic. Recently, research has focused on climate change undermining the irrigation-based agriculture on which an advanced urban society was ultimately dependent. Soil samples around the skeletons from which samples were sent for DNA analysis have also been despatched. Traces of parasites, found in these skeletons, may tell archaeologists what the people of the Indus Valley civilization ate. Three-dimensional modelling technology will also allow a reconstruction of the physical appearance of the dead. “For the first time we will see the face of these people,” Shinde said.

In Rakhigarhi village, there are mixed emotions about the forthcoming revelations about the site. Chand, a self-appointed guide from Rakhigarhi, hopes the local government will finally fulfil long standing promises to build a museum, an auditorium and hotel for tourists there. “This is a neglected site and now that will change. This place should be as popular as the Taj Mahal. There should be hundreds, thousands of visitors coming,” Chand said.

Q. Which of the following could be a possible reason as to why Chand thinks Rakhigarhi is a neglected site?

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The origins of the people of the Indus Valley civilization has prompted a long-running argument that has lasted for more than five decades.

Some scholars have suggested that they were originally migrants from upland plateaux to the west. Others have maintained the civilization was made up of indigenous local groups, while some have said it was a mixture of both, and part of a network of different communities in the region. Experts have also debated whether the civilization succumbed to a traumatic invasion by so-called “Aryans” whose chariots they were unable to resist, or in fact peaceably assimilated a series of waves of migration over many decades or centuries.

A new research will provide definitive answers, at least for the population of Rakhigarhi. It is a key site in the Indus Valley civilization which ruled a more than 1 million sq km swath of the Asian subcontinent during the bronze age and was as advanced and powerful as its better known contemporary counterparts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. “There is already evidence of intermarriage and mixing through trade and so forth for a long time and the DNA will tell us for sure,” said Vasant Shinde, an Indian archaeologist leading current excavations at Rakhigarhi.

Shinde’s conclusions will be published in the new year. They are based on DNA sequences derived from four skeletons excavated eight months ago and checked against DNA data from tens of thousands of people from all across the subcontinent, central Asia and Iran.

The conclusions from the new research on the skeletal DNA sample are likely to be controversial in a region riven by religious, ethnic and nationalist tensions. Hostile neighbours India and Pakistan have fought three wars since winning their independence from the British in 1947, and have long squabbled over the true centre of the Indus civilization, which straddles the border between the countries. Shinde said Rakhigarhi might have been a bigger city than either Mohenjodaro or Harappa, two sites in Pakistan previously considered the centre of the Indus civilization. Some in India will also be keen to claim any new research supports their belief that the Rig Veda, an ancient text sacred to Hindus compiled shortly after the demise of the Indus Valley civilization, is reliable as an historical record.

The question of links between today’s inhabitants of the area and those who lived, farmed, and died millennia ago has also prompted fierce argument. There are other mysteries too. The Indus Valley civilization flourished for three thousand years before disappearing suddenly around 1500 BC. Theories range from the drying up of local rivers to an epidemic. Recently, research has focused on climate change undermining the irrigation-based agriculture on which an advanced urban society was ultimately dependent. Soil samples around the skeletons from which samples were sent for DNA analysis have also been despatched. Traces of parasites, found in these skeletons, may tell archaeologists what the people of the Indus Valley civilization ate. Three-dimensional modelling technology will also allow a reconstruction of the physical appearance of the dead. “For the first time we will see the face of these people,” Shinde said.

In Rakhigarhi village, there are mixed emotions about the forthcoming revelations about the site. Chand, a self-appointed guide from Rakhigarhi, hopes the local government will finally fulfil long standing promises to build a museum, an auditorium and hotel for tourists there. “This is a neglected site and now that will change. This place should be as popular as the Taj Mahal. There should be hundreds, thousands of visitors coming,” Chand said.

Q. Which of the following statements about Rakhigarhi can be understood from the passage?

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The origins of the people of the Indus Valley civilization has prompted a long-running argument that has lasted for more than five decades.

Some scholars have suggested that they were originally migrants from upland plateaux to the west. Others have maintained the civilization was made up of indigenous local groups, while some have said it was a mixture of both, and part of a network of different communities in the region. Experts have also debated whether the civilization succumbed to a traumatic invasion by so-called “Aryans” whose chariots they were unable to resist, or in fact peaceably assimilated a series of waves of migration over many decades or centuries.

A new research will provide definitive answers, at least for the population of Rakhigarhi. It is a key site in the Indus Valley civilization which ruled a more than 1 million sq km swath of the Asian subcontinent during the bronze age and was as advanced and powerful as its better known contemporary counterparts in Egypt and Mesopotamia. “There is already evidence of intermarriage and mixing through trade and so forth for a long time and the DNA will tell us for sure,” said Vasant Shinde, an Indian archaeologist leading current excavations at Rakhigarhi.

Shinde’s conclusions will be published in the new year. They are based on DNA sequences derived from four skeletons excavated eight months ago and checked against DNA data from tens of thousands of people from all across the subcontinent, central Asia and Iran.

The conclusions from the new research on the skeletal DNA sample are likely to be controversial in a region riven by religious, ethnic and nationalist tensions. Hostile neighbours India and Pakistan have fought three wars since winning their independence from the British in 1947, and have long squabbled over the true centre of the Indus civilization, which straddles the border between the countries. Shinde said Rakhigarhi might have been a bigger city than either Mohenjodaro or Harappa, two sites in Pakistan previously considered the centre of the Indus civilization. Some in India will also be keen to claim any new research supports their belief that the Rig Veda, an ancient text sacred to Hindus compiled shortly after the demise of the Indus Valley civilization, is reliable as an historical record.

The question of links between today’s inhabitants of the area and those who lived, farmed, and died millennia ago has also prompted fierce argument. There are other mysteries too. The Indus Valley civilization flourished for three thousand years before disappearing suddenly around 1500 BC. Theories range from the drying up of local rivers to an epidemic. Recently, research has focused on climate change undermining the irrigation-based agriculture on which an advanced urban society was ultimately dependent. Soil samples around the skeletons from which samples were sent for DNA analysis have also been despatched. Traces of parasites, found in these skeletons, may tell archaeologists what the people of the Indus Valley civilization ate. Three-dimensional modelling technology will also allow a reconstruction of the physical appearance of the dead. “For the first time we will see the face of these people,” Shinde said.

In Rakhigarhi village, there are mixed emotions about the forthcoming revelations about the site. Chand, a self-appointed guide from Rakhigarhi, hopes the local government will finally fulfil long standing promises to build a museum, an auditorium and hotel for tourists there. “This is a neglected site and now that will change. This place should be as popular as the Taj Mahal. There should be hundreds, thousands of visitors coming,” Chand said.

Q. According to the passage, which of the following can provide information about the people of Indus Valley civilization?

I. Soil samples around Rakhigarhi's contours.

II. DNA sequences derived from the four skeletons excavated near Rakhigarhi.

III. Traces of parasites found in the skeletal structures.

IV. Three-dimensional modelling technology.

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The issues and preoccupations of the 21st century present new and often fundamentally different types of challenges from those that faced the world in 1945, when the United Nations was founded. As new realities and challenges have emerged, so too have new expectations for action and new standards of conduct in national and international affairs. Since, for example, the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, it has become evident that the war against terrorism the world must now fight – one with no contested frontiers and a largely invisible enemy – is one like no other war before it.

Many new international institutions have been created to meet these changed circumstances. In key respects, however, the mandates and capacity of international institutions have not kept pace with international needs or modern expectations. Above all, the issue of international intervention for human protection purposes is a clear and compelling example of concerted action urgently being needed to bring international norms and institutions in line with international needs and expectations.

The current debate on intervention for human protection purposes is itself both a product and a reflection of how much has changed since the UN was established. The current debate takes place in the context of a broadly expanded range of state, non-state, and institutional actors, and increasingly evident interaction and interdependence among them. It is a debate that reflects new sets of issues and new types of concerns. It is a debate that is being conducted within the framework of new standards of conduct for states and individuals, and in a context of greatly increased expectations for action. And it is a debate that takes place within an institutional framework that since the end of the Cold War has held out the prospect of effective joint international action to address issues of peace, security, human rights and sustainable development on a global scale.

With new actors – not least new states, with the UN growing from 51 member states in 1945 to 189 today – has come a wide range of new voices, perspectives, interests, experiences and aspirations. Together, these new international actors have added both depth and texture to the increasingly rich tapestry of international society and important institutional credibility and practical expertise to the wider debate.

Prominent among the range of important new actors are a number of institutional actors and mechanisms, especially in the areas of human rights and human security. They have included, among others, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, both created in 1993, and its sister tribunals for Rwanda established in 1994 and Sierra Leone in 2001.

The International Criminal Court, whose creation was decided in 1998, will begin operation when 60 countries have ratified its Statute. In addition to the new institutions, established ones such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the ICRC and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, have been ever more active.

Nearly as significant has been the emergence of many new non-state actors in international affairs – including especially a large number of NGOs dealing with global matters; a growing number of media and academic institutions with worldwide reach; and an increasingly diverse array of armed non-state actors ranging from national and international terrorists to traditional rebel movements and various organized criminal groupings. These new non-state actors, good or bad, have forced the debate about intervention for human protection purposes to be conducted in front of a broader public, while at the same time adding new elements to the agenda.

Q. A criticism that the author levies against international institutions is that

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The issues and preoccupations of the 21st century present new and often fundamentally different types of challenges from those that faced the world in 1945, when the United Nations was founded. As new realities and challenges have emerged, so too have new expectations for action and new standards of conduct in national and international affairs. Since, for example, the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, it has become evident that the war against terrorism the world must now fight – one with no contested frontiers and a largely invisible enemy – is one like no other war before it.

Many new international institutions have been created to meet these changed circumstances. In key respects, however, the mandates and capacity of international institutions have not kept pace with international needs or modern expectations. Above all, the issue of international intervention for human protection purposes is a clear and compelling example of concerted action urgently being needed to bring international norms and institutions in line with international needs and expectations.

The current debate on intervention for human protection purposes is itself both a product and a reflection of how much has changed since the UN was established. The current debate takes place in the context of a broadly expanded range of state, non-state, and institutional actors, and increasingly evident interaction and interdependence among them. It is a debate that reflects new sets of issues and new types of concerns. It is a debate that is being conducted within the framework of new standards of conduct for states and individuals, and in a context of greatly increased expectations for action. And it is a debate that takes place within an institutional framework that since the end of the Cold War has held out the prospect of effective joint international action to address issues of peace, security, human rights and sustainable development on a global scale.

With new actors – not least new states, with the UN growing from 51 member states in 1945 to 189 today – has come a wide range of new voices, perspectives, interests, experiences and aspirations. Together, these new international actors have added both depth and texture to the increasingly rich tapestry of international society and important institutional credibility and practical expertise to the wider debate.

Prominent among the range of important new actors are a number of institutional actors and mechanisms, especially in the areas of human rights and human security. They have included, among others, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, both created in 1993, and its sister tribunals for Rwanda established in 1994 and Sierra Leone in 2001.

The International Criminal Court, whose creation was decided in 1998, will begin operation when 60 countries have ratified its Statute. In addition to the new institutions, established ones such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the ICRC and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, have been ever more active.

Nearly as significant has been the emergence of many new non-state actors in international affairs – including especially a large number of NGOs dealing with global matters; a growing number of media and academic institutions with worldwide reach; and an increasingly diverse array of armed non-state actors ranging from national and international terrorists to traditional rebel movements and various organized criminal groupings. These new non-state actors, good or bad, have forced the debate about intervention for human protection purposes to be conducted in front of a broader public, while at the same time adding new elements to the agenda.

Q. The author presents the example of the terrorists attacks of September 9, 2011 to

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The issues and preoccupations of the 21st century present new and often fundamentally different types of challenges from those that faced the world in 1945, when the United Nations was founded. As new realities and challenges have emerged, so too have new expectations for action and new standards of conduct in national and international affairs. Since, for example, the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, it has become evident that the war against terrorism the world must now fight – one with no contested frontiers and a largely invisible enemy – is one like no other war before it.

Many new international institutions have been created to meet these changed circumstances. In key respects, however, the mandates and capacity of international institutions have not kept pace with international needs or modern expectations. Above all, the issue of international intervention for human protection purposes is a clear and compelling example of concerted action urgently being needed to bring international norms and institutions in line with international needs and expectations.

The current debate on intervention for human protection purposes is itself both a product and a reflection of how much has changed since the UN was established. The current debate takes place in the context of a broadly expanded range of state, non-state, and institutional actors, and increasingly evident interaction and interdependence among them. It is a debate that reflects new sets of issues and new types of concerns. It is a debate that is being conducted within the framework of new standards of conduct for states and individuals, and in a context of greatly increased expectations for action. And it is a debate that takes place within an institutional framework that since the end of the Cold War has held out the prospect of effective joint international action to address issues of peace, security, human rights and sustainable development on a global scale.

With new actors – not least new states, with the UN growing from 51 member states in 1945 to 189 today – has come a wide range of new voices, perspectives, interests, experiences and aspirations. Together, these new international actors have added both depth and texture to the increasingly rich tapestry of international society and important institutional credibility and practical expertise to the wider debate.

Prominent among the range of important new actors are a number of institutional actors and mechanisms, especially in the areas of human rights and human security. They have included, among others, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, both created in 1993, and its sister tribunals for Rwanda established in 1994 and Sierra Leone in 2001.

The International Criminal Court, whose creation was decided in 1998, will begin operation when 60 countries have ratified its Statute. In addition to the new institutions, established ones such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the ICRC and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, have been ever more active.

Nearly as significant has been the emergence of many new non-state actors in international affairs – including especially a large number of NGOs dealing with global matters; a growing number of media and academic institutions with worldwide reach; and an increasingly diverse array of armed non-state actors ranging from national and international terrorists to traditional rebel movements and various organized criminal groupings. These new non-state actors, good or bad, have forced the debate about intervention for human protection purposes to be conducted in front of a broader public, while at the same time adding new elements to the agenda.

Q. Which of the following is true regarding the debate on intervention for human protection purposes?

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The first era of innovation – that of the lone inventor – encompassed much of human history. Innovators occasionally formed or latched on to companies to exploit the full potential of their ideas, but most seminal innovations developed before about 1915 are closely associated with the individuals behind them: Gutenberg’s press. Whitney’s cotton gin. Edison’s lightbulb. The Wright brothers’ plane. Ford’s assembly line (actually as much a business model as a technology).

With the perfection of the assembly line, a century ago, the increasing complexity and cost of innovation pushed it out of individuals’ reach, driving more company-led efforts. A combination of longer-term perspectives and less stifling corporate bureaucracies meant that many organizations would happily tolerate experimental efforts. Thus, the heroes of this second era worked in corporate labs, and corporations evolved from innovation exploiters into innovation creators. Many of the notable commercial inventions of the next 60 years came from these labs: DuPont’s miracle molecules (including nylon); Procter & Gamble’s Crest, Pampers, and Tide brands; the U-2 spy plane and SR-71 Blackbird fighter jet from Lockheed Martin’s famed Skunk Works.

The seeds of the third era were planted in the late 1950s and the 1960s, as companies started to become too big and bureaucratic to handle at-the-fringes exploration. The restless individualism of baby boomers clashed with increasingly hierarchical organizations. Innovators began to leave companies, band with like-minded “rebels,” and form new companies. Given the scale required to innovate, however, these rebels needed new forms of funding. Hence the emergence of the VC-backed start-up. The third era came into its own in the 1970s, with the establishment of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Sequoia Capital. These and similar institutions helped to support the formation of Apple, Microsoft, Cisco Systems, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Life became even harder for innovators in big companies as the capital markets’ expectations for short-term performance grew.

The technologies birthed during this era and the globalization of world markets have dramatically accelerated the pace of change. Over the past 50 years corporate life spans by some measures have decreased by close to 50%. Back in 2000, Microsoft was an unstoppable monopoly, Apple was playing at the fringes of the computer market, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was a student at Phillips Exeter Academy, and Google was a technology in search of a business model.

This breathless pace, and the conditions and tools that enable it, bring us to the fourth era – when corporate catalysts can have a transformational impact. Whereas the inventions that characterized the first three eras were typically (but not always) technological breakthroughs, fourth-era innovations are likely to involve business models. One analysis shows that from 1997 to 2007 more than half of the companies that made it onto the Fortune 500 before their 25th birthdays – including Amazon, Starbucks, and AutoNation – were business model innovators.

Today it’s easier than ever to innovate, which may suggest that it’s an ideal time to start a business. After all, a wealth of low-cost or no-cost online tools, coupled with hyperconnected markets, put innovation capabilities into the hands of the masses and allow ideas to rapidly spread.

Q. All the following can be understood from the passage EXCEPT:

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The first era of innovation – that of the lone inventor – encompassed much of human history. Innovators occasionally formed or latched on to companies to exploit the full potential of their ideas, but most seminal innovations developed before about 1915 are closely associated with the individuals behind them: Gutenberg’s press. Whitney’s cotton gin. Edison’s lightbulb. The Wright brothers’ plane. Ford’s assembly line (actually as much a business model as a technology).

With the perfection of the assembly line, a century ago, the increasing complexity and cost of innovation pushed it out of individuals’ reach, driving more company-led efforts. A combination of longer-term perspectives and less stifling corporate bureaucracies meant that many organizations would happily tolerate experimental efforts. Thus, the heroes of this second era worked in corporate labs, and corporations evolved from innovation exploiters into innovation creators. Many of the notable commercial inventions of the next 60 years came from these labs: DuPont’s miracle molecules (including nylon); Procter & Gamble’s Crest, Pampers, and Tide brands; the U-2 spy plane and SR-71 Blackbird fighter jet from Lockheed Martin’s famed Skunk Works.

The seeds of the third era were planted in the late 1950s and the 1960s, as companies started to become too big and bureaucratic to handle at-the-fringes exploration. The restless individualism of baby boomers clashed with increasingly hierarchical organizations. Innovators began to leave companies, band with like-minded “rebels,” and form new companies. Given the scale required to innovate, however, these rebels needed new forms of funding. Hence the emergence of the VC-backed start-up. The third era came into its own in the 1970s, with the establishment of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Sequoia Capital. These and similar institutions helped to support the formation of Apple, Microsoft, Cisco Systems, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Life became even harder for innovators in big companies as the capital markets’ expectations for short-term performance grew.

The technologies birthed during this era and the globalization of world markets have dramatically accelerated the pace of change. Over the past 50 years corporate life spans by some measures have decreased by close to 50%. Back in 2000, Microsoft was an unstoppable monopoly, Apple was playing at the fringes of the computer market, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was a student at Phillips Exeter Academy, and Google was a technology in search of a business model.

This breathless pace, and the conditions and tools that enable it, bring us to the fourth era – when corporate catalysts can have a transformational impact. Whereas the inventions that characterized the first three eras were typically (but not always) technological breakthroughs, fourth-era innovations are likely to involve business models. One analysis shows that from 1997 to 2007 more than half of the companies that made it onto the Fortune 500 before their 25th birthdays – including Amazon, Starbucks, and AutoNation – were business model innovators.

Today it’s easier than ever to innovate, which may suggest that it’s an ideal time to start a business. After all, a wealth of low-cost or no-cost online tools, coupled with hyperconnected markets, put innovation capabilities into the hands of the masses and allow ideas to rapidly spread.

Q. Which of the following is not a reason mentioned in the passage that pushed innovators closer to organisations and corporate labs in the second era of innovation?

DIRECTIONS for questions: The passage given below is accompanied by a set of three questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

The first era of innovation – that of the lone inventor – encompassed much of human history. Innovators occasionally formed or latched on to companies to exploit the full potential of their ideas, but most seminal innovations developed before about 1915 are closely associated with the individuals behind them: Gutenberg’s press. Whitney’s cotton gin. Edison’s lightbulb. The Wright brothers’ plane. Ford’s assembly line (actually as much a business model as a technology).

With the perfection of the assembly line, a century ago, the increasing complexity and cost of innovation pushed it out of individuals’ reach, driving more company-led efforts. A combination of longer-term perspectives and less stifling corporate bureaucracies meant that many organizations would happily tolerate experimental efforts. Thus, the heroes of this second era worked in corporate labs, and corporations evolved from innovation exploiters into innovation creators. Many of the notable commercial inventions of the next 60 years came from these labs: DuPont’s miracle molecules (including nylon); Procter & Gamble’s Crest, Pampers, and Tide brands; the U-2 spy plane and SR-71 Blackbird fighter jet from Lockheed Martin’s famed Skunk Works.

The seeds of the third era were planted in the late 1950s and the 1960s, as companies started to become too big and bureaucratic to handle at-the-fringes exploration. The restless individualism of baby boomers clashed with increasingly hierarchical organizations. Innovators began to leave companies, band with like-minded “rebels,” and form new companies. Given the scale required to innovate, however, these rebels needed new forms of funding. Hence the emergence of the VC-backed start-up. The third era came into its own in the 1970s, with the establishment of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Sequoia Capital. These and similar institutions helped to support the formation of Apple, Microsoft, Cisco Systems, Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Life became even harder for innovators in big companies as the capital markets’ expectations for short-term performance grew.

The technologies birthed during this era and the globalization of world markets have dramatically accelerated the pace of change. Over the past 50 years corporate life spans by some measures have decreased by close to 50%. Back in 2000, Microsoft was an unstoppable monopoly, Apple was playing at the fringes of the computer market, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was a student at Phillips Exeter Academy, and Google was a technology in search of a business model.

This breathless pace, and the conditions and tools that enable it, bring us to the fourth era – when corporate catalysts can have a transformational impact. Whereas the inventions that characterized the first three eras were typically (but not always) technological breakthroughs, fourth-era innovations are likely to involve business models. One analysis shows that from 1997 to 2007 more than half of the companies that made it onto the Fortune 500 before their 25th birthdays – including Amazon, Starbucks, and AutoNation – were business model innovators.

Today it’s easier than ever to innovate, which may suggest that it’s an ideal time to start a business. After all, a wealth of low-cost or no-cost online tools, coupled with hyperconnected markets, put innovation capabilities into the hands of the masses and allow ideas to rapidly spread.

Q. Google being in search of a business model in 2000 was mentioned by the author to

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the questions consists of a paragraph with three blanks. For each blank choose one numbered word/ phrase from the corresponding column of choices that will best complete the text. Key in the appropriate numbers of the words/ phrases for each blank, in the correct sequential order, in the input box given below the question. For example, if you think that words/ phrases labelled (1), (5) and (9) can complete the text correctly, then enter 159 as your answer in the input box. (Note: Only one word/ phrase in each column can fill the respective blank correctly.)

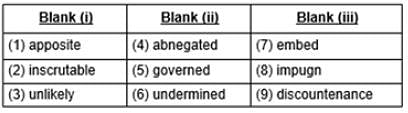

Ecologists and economists made ________(i)__________ partners -- indeed, these disciplines have often appeared at odds with, and determined to ignore, each other. As Robert Costanza, the founding president of the International Society for Ecological Economics, acknowledged, "Ecology, as it is currently practiced, sometimes deals with human impacts on ecosystems, but the more common tendency is to stick to 'natural' systems." The modeling of ecological communities or systems seemed purposely to leave out the human economy. At the same time, economists either took for granted or ignored the principles, powers, or forces that ecologists believed ___________(ii)____________ the world's natural communities. The market mechanism, or competitive equilibrium, that mainstream economists studied assigned no role to the natural ecosystem. So the new discipline “Ecological economics” seeks to ___________(iii)____________ the study of economics within a larger understanding of how ecosystems work.

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the questions consists of a paragraph with three blanks. For each blank choose one numbered word/ phrase from the corresponding column of choices that will best complete the text. Key in the appropriate numbers of the words/ phrases for each blank, in the correct sequential order, in the input box given below the question. For example, if you think that words/ phrases labelled (1), (5) and (9) can complete the text correctly, then enter 159 as your answer in the input box. (Note: Only one word/ phrase in each column can fill the respective blank correctly.)

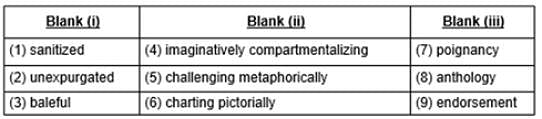

Many parts of India are familiar to us through their overexposure in the travel media, but images of the Taj Mahal bathed in the golden glow of sunrise offer a rather ___________(i)____________ view of a teeming, steaming, wild and wonderful country. This new, marvellous collection of photographs by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Sebastiao Salgado corrects the balance, gathering together images from 150 years to provide a true representation of India's many facets. It explores every aspect of the country's modern history from the demise of the Mughal Empire to the rise of Bollywood. Overall the collection has achieved its aim of ___________(ii)____________ the social and cultural progress of India. An elegant introduction provides a historical narrative to accompany the photographs, while a noted photojournalist explains how the images were selected. Together, these elements form a timely and thought-provoking addition to the ever-expanding __________(iii)____________ of literature on India.

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the questions consists of a paragraph with three blanks. For each blank choose one numbered word/ phrase from the corresponding column of choices that will best complete the text. Key in the appropriate numbers of the words/ phrases for each blank, in the correct sequential order, in the input box given below the question. For example, if you think that words/ phrases labelled (1), (5) and (9) can complete the text correctly, then enter 159 as your answer in the input box. (Note: Only one word/ phrase in each column can fill the respective blank correctly.)

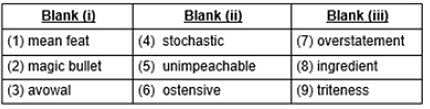

At the individual level, elements of emotional intelligence can be identified, assessed, and upgraded. At the group level, it means fine-tuning the interpersonal dynamics that make groups smarter. At the organizational level, it means revising the value hierarchy to make emotional intelligence a priority – in the concrete terms of hiring, training and development, performance evaluation, and promotions. At the corporate level, emotional intelligence is no ___________(i)____________, no guarantee of more market share or a healthier bottom line. The ecology of a corporation is extraordinarily ___________(ii)____________ and complex, and no single intervention or change can fix every problem.

But, as the saying goes, “It's all done with people,” and if the human ___________(iii)_____________ is ignored, then nothing else will work as well as it might. In the years to come, companies in which people collaborate best will have a competitive edge.

DIRECTIONS for questions: In each of the following questions, the phrase in bold is used in four different sentences. Select the option in which the usage of the phrase is CORRECT or APPROPRIATE as your answer.

Sine qua non

DIRECTIONS for questions: In each of the following questions, the phrase in bold is used in four different sentences. Select the option in which the usage of the phrase is CORRECT or APPROPRIATE as your answer.

Carte blanche

DIRECTIONS for questions: In each of the following questions, the phrase in bold is used in four different sentences. Select the option in which the usage of the phrase is CORRECT or APPROPRIATE as your answer.

Prima facie

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the following questions has a paragraph which is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the alternative that best captures the essence of the paragraph.

The apotheosis of the pop in postmodernism art marked a whole new marriage between high and low art. For the artistic viability of postmodernism was a direct consequence, again, not of any new facts about art, but of facts about the new importance of mass commercial culture. We seem no longer united so much by common beliefs as by common images: what binds us became what we stand witness to Nobody sees this as a good change.

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the following questions has a paragraph which is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the alternative that best captures the essence of the paragraph.

The concept of personal rights and freedoms that guides our legal institutions is outdated. It is built on a model of a free individual who enjoys an untouchable inner life. Now, though, our thoughts can be invaded before they have even been developed – and in a way, perhaps this is nothing new. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman used to say that he thought with his notebook. Without a pen and pencil, a great deal of complex reflection and analysis would never have been possible. If the extended mind view is right, then even technologies such as those used in the smartphone would merit recognition and protection as a part of the essential toolkit of the mind.

DIRECTIONS for questions: Each of the following questions has a paragraph which is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the alternative that best captures the essence of the paragraph.

When Thomas Steitz, Ada Yonath, and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their research, in 2009, they acknowledged a debt. Without the work of two of the Physics Laureates that year, the chemists would have lacked the CCD detectors, or high-quality imaging hardware, they used to model and image ribosomes, sites of protein synthesis within a cell. Collaboration in science has become commonplace today, and we’re seeing the benefits. But many of its fruits are unintended. As Ramakrishnan points out, inventions in one discipline can build on – and spur – basic research in many others, often unwittingly. It’s a virtuous cycle, and scientists take joy in exploiting all of it. “Scientists are very promiscuous,” he says, “and the good ones are the most promiscuous.”

DIRECTIONS for questions: Read each of the following paragraphs and answer the question given below it.

When asked to account for the cultural backwardness of Aboriginal Australians, many white Australians have a simple answer: supposed deficiencies of the Aborigines themselves. How else can one account for the fact that white English colonists created a literate, food producing, industrial democracy within a few decades of colonizing a continent whose inhabitants after more than 40000 years were still nonliterate hunter-gatherers. It seems like a perfectly controlled experiment in the evolution of human societies. The continent was the same; only the people were different. The explanation for the differences between Native Australian and European-Australian societies must lie in the different people composing them. The logic behind this racist conclusion appears compelling. However, it contains a simple error.

Q. Which of the following, if true, most likely highlights that error?

DIRECTIONS for questions: Read each of the following paragraphs and answer the question given below it.

A large group of students were each given a headset and told that a company making high-tech headphones wanted to test how well they worked when the listener was in motion or moving his or her head. All of the students listened to the same songs and then heard a radio editorial arguing that tuition at their university should be raised from its present level of $587 to $750. A third was told that while they listened to the taped radio editorial they should nod their heads vigorously up and down, an action usually associated with approval; the next third to shake their heads from side to side, an action usually associated with refusal; the final third to keep their heads still. Later, the students were given a questionnaire asking them questions about the quality of the songs and effect of the shaking on the quality. Slipped in at the end was the question the experimenters really wanted an answer to: “What do you feel would be an appropriate dollar amount for undergraduate tuition per year?” Which of the following combinations of statements, if true, would point to a conclusion that the mere act of nodding their head or shaking their head would positively or adversely affect their estimation of the persuasiveness of the radio editorial, respectively?

I. Those who were told to nod their heads wanted the tuition to rise to $646, on average.

II. Those who were told to nod their heads wanted the tuition to fall on average to $467 a year.

III. Those who were told to shake their heads wanted the tuition to rise to $646, on average.

IV. Those who were told not to move their heads on an average guessed that $585 would be appropriate for the tuition, just about where the tuition was already.

DIRECTIONS for questions: Read each of the following paragraphs and answer the question given below it.

It's perhaps ironic that Fermat’s greatest fame rests on a theorem that he almost certainly didn’t prove. He apparently claimed a proof and the result is now known to be true, but the verdict of history is that the methods available to him weren’t up to the task. His claim to possess a proof exists only as a marginal note in a book, which doesn’t even survive as an original document, so it could have been made prematurely.

In mathematical research it’s not unusual to wake up in the morning convinced you’ve proved something important only to see the proof evaporate by noon when you find a mistake.

Q. Which of the following, if proven to be true, would strengthen the case for Fermat proving his most famous theorem?

DIRECTIONS for questions: Five sentences are given with a blank in the following question. Four words are also given below the sentences. The blank in each sentence can be filled by one or more of the five words given. Each word can go into any number of sentences. Note that the sentence can change contexts depending on the use of different words which can be appropriate. Identify the number of sentences each word can go into and enter the maximum number of sentences that any word can fit in. For example, if you think that a word goes into a maximum of three sentences, then enter 3 as your answer in the input box given below the question.

i. All radars are programmed to ______________________ the satellite's progress across the stratosphere.

ii. Meteorologists _______________ an active hurricane season because of warmer ocean-surface temperatures.

iii. The new principal of the college thought it necessary to _______________ regular tests for students.

iv. The ideological group is driven by local grievances yet has global aspirations, helping to ________________ rebellion in such troubled places as northern Nigeria and Yemen.

v. It is difficult to _____________ the movement of stocks in the share market without using fundamental and technical indicators.