CAT Mock Test - 11 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test - 11

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Philosophical games aside, the practical importance of understanding the brain basis of consciousness is easy to appreciate. General anaesthesia has to count as one of the greatest inventions of all time. Less happily, distressing disturbances of consciousness can accompany brain injuries and mental illnesses for the increasing number of us, me included, who encounter these conditions. And for each one of us, conscious experiences change throughout life, from the blooming and buzzing confusion of early life, through the apparent though probably illusory and certainly not universal clarity of adulthood, and on to our final drift into the gradual — and for some, disorientingly rapid — dissolution of the self as neurodegenerative decay sets in.

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Q. Why does the author think that ''General anaesthesia has to count as one of the greatest inventions of all time''?

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Philosophical games aside, the practical importance of understanding the brain basis of consciousness is easy to appreciate. General anaesthesia has to count as one of the greatest inventions of all time. Less happily, distressing disturbances of consciousness can accompany brain injuries and mental illnesses for the increasing number of us, me included, who encounter these conditions. And for each one of us, conscious experiences change throughout life, from the blooming and buzzing confusion of early life, through the apparent though probably illusory and certainly not universal clarity of adulthood, and on to our final drift into the gradual — and for some, disorientingly rapid — dissolution of the self as neurodegenerative decay sets in.

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Q. In context of the passage, what purpose do Freud's "three strikes" serve?

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Philosophical games aside, the practical importance of understanding the brain basis of consciousness is easy to appreciate. General anaesthesia has to count as one of the greatest inventions of all time. Less happily, distressing disturbances of consciousness can accompany brain injuries and mental illnesses for the increasing number of us, me included, who encounter these conditions. And for each one of us, conscious experiences change throughout life, from the blooming and buzzing confusion of early life, through the apparent though probably illusory and certainly not universal clarity of adulthood, and on to our final drift into the gradual — and for some, disorientingly rapid — dissolution of the self as neurodegenerative decay sets in.

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Q. Which of the following statements is the author most likely to agree with?

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Directions: The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Philosophical games aside, the practical importance of understanding the brain basis of consciousness is easy to appreciate. General anaesthesia has to count as one of the greatest inventions of all time. Less happily, distressing disturbances of consciousness can accompany brain injuries and mental illnesses for the increasing number of us, me included, who encounter these conditions. And for each one of us, conscious experiences change throughout life, from the blooming and buzzing confusion of early life, through the apparent though probably illusory and certainly not universal clarity of adulthood, and on to our final drift into the gradual — and for some, disorientingly rapid — dissolution of the self as neurodegenerative decay sets in.

At each stage in this process, you exist, but the notion that there is a single unique conscious self (a soul?) that persists over time may be grossly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most compelling aspects of the mystery of consciousness is the nature of self. Is consciousness possible without self-consciousness? And if so, would it still matter so much?

Answers to difficult questions like these have many implications for how we think about the world and the life it contains. When does consciousness begin in development? Does it emerge at birth, or is it present even in the womb? What about consciousness in nonhuman animals — and not just in primates and other mammals, but in otherworldly creatures like the octopus and perhaps even in simple organisms such as nematode worms or bacteria?

Despite his now-tarnished reputation among neuroscientists, Sigmund Freud was right about many things. Looking back through the history of science, he identified three "strikes" against the perceived self-importance of the human species, each marking a major scientific advance that was strongly resisted at the time.

The first was by Copernicus, who showed with his heliocentric theory that the Earth rotates around the sun and not the other way around. With this dawned the realisation that we are not at the centre of the universe; we are just a speck somewhere out there in the vastness, a pale blue dot suspended in the abyss.

Next came Darwin, who revealed that we share common ancestry with all other living things, a realisation that is — astonishingly — still resisted in some parts of the world even today.

Immodestly, Freud's third strike against human exceptionalism was his own theory of the unconscious mind, which challenged the idea that our mental lives are under our conscious, rational control. While he may have been off target in the details, he was absolutely right to point out that a naturalistic explanation of mind and consciousness would be a further, and perhaps final, dethronement of humankind.

These shifts in how we see ourselves are to be welcomed. With each new advance in our understanding comes a new sense of wonder and a new ability to see ourselves as less apart from — and more a part of — the rest of nature.

Our conscious experiences are part of nature just as our bodies are, just as our world is. And when life ends, consciousness will end too. When I think about this, I am transported back to my experience — my non-experience — of anaesthesia. To its oblivion, perhaps comforting, but oblivion nonetheless. The novelist Julian Barnes, in his meditation on mortality, puts it perfectly. When the end of consciousness comes, there is nothing — really nothing — to be frightened of.

Q. Which one of the following best describes the word 'oblivion' in the context of the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Ask any hardcore substance addict (try this only when they are sober) how his or her very first experience was, and they will for sure tell you it was not a very pleasant one. The violent cough of the first puff, the distaste of the first sip, the bitterness of the powder, hits them first; the feel-good factor and ecstasy that ends up in an unbreakable bond comes slowly, and much later. That's why we urge you to start the new addiction programme now, whatever be the initial hiccups.

Every patient is different, from shy and submissive to bold and aggressive; some are dead scared of injections while others go in for heart surgery with a smile. But the 'argumentative' types are special and the most difficult to handle; give them a piece of advice and they would be ready with an instant counter-argument. But it is these argumentative ones who teach the old doctors a new trick or two, by asking odd and embarrassing questions, forcing us to dig up old medical journals or try surfing the Net. That's exactly what happened when this young man asked me: ''I am not overweight, neither do I have diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease. Then why do you want me to exercise?'' The answer to that question is far from simple.

fMRI, or functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, is a system that can track blood circulation and show the intensity of activation of a localised area of the brain during a specific activity. Reading, for example, activates the occipital cortex, speaking lights up the speech area, while decision-making switches on the frontal cortex.

In a study researchers looked into the fMRI pattern in those who do regular exercise, and found that a 'C'-shaped structure, the caudate nucleus, a part of the basal ganglia, becomes highly active. This is caused by flooding of that area by a neurotransmitter called dopamine. This area is the reward area of the brain, and such activation makes the person feel happy. But what stumped the researchers was that the pattern of activation matched the fMRI imaging pattern of a nicotine or cocaine addict. The fMRI image of a cocaine addict who is high and a health freak doing exercise had an uncanny similarity from the perspective of neurochemistry and brain imaging.

Lack of exercise is a technology problem. Today we don't even walk to our neighbour to chat; we pick up the mobile instead. And then there is the lure of sitting back at home knowing that the world of entertainment is just a click away.

Some 150 minutes of exercise a week translates into 30 minutes a day for five days a week, or two 15 minute sessions of brisk walking. And that 15 minutes of apparent 'waste-of-time' would not only reduce your 'waist-in-time' but also reduce the chances of your developing high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, each by 30 per cent. A similar reduction of chance of depression and consequent improvement of self-confidence would be a bonus.

Powering your life and staying heart healthy is possible by getting hooked on to a new addiction - 'daily exercise'. All you need is to hold on till the initial hiccough is over - and then it would be bliss.

Q. It can be inferred that the author of the passage makes a case for inculcating the habit of exercising because

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Ask any hardcore substance addict (try this only when they are sober) how his or her very first experience was, and they will for sure tell you it was not a very pleasant one. The violent cough of the first puff, the distaste of the first sip, the bitterness of the powder, hits them first; the feel-good factor and ecstasy that ends up in an unbreakable bond comes slowly, and much later. That's why we urge you to start the new addiction programme now, whatever be the initial hiccups.

Every patient is different, from shy and submissive to bold and aggressive; some are dead scared of injections while others go in for heart surgery with a smile. But the 'argumentative' types are special and the most difficult to handle; give them a piece of advice and they would be ready with an instant counter-argument. But it is these argumentative ones who teach the old doctors a new trick or two, by asking odd and embarrassing questions, forcing us to dig up old medical journals or try surfing the Net. That's exactly what happened when this young man asked me: ''I am not overweight, neither do I have diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease. Then why do you want me to exercise?'' The answer to that question is far from simple.

fMRI, or functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, is a system that can track blood circulation and show the intensity of activation of a localised area of the brain during a specific activity. Reading, for example, activates the occipital cortex, speaking lights up the speech area, while decision-making switches on the frontal cortex.

In a study researchers looked into the fMRI pattern in those who do regular exercise, and found that a 'C'-shaped structure, the caudate nucleus, a part of the basal ganglia, becomes highly active. This is caused by flooding of that area by a neurotransmitter called dopamine. This area is the reward area of the brain, and such activation makes the person feel happy. But what stumped the researchers was that the pattern of activation matched the fMRI imaging pattern of a nicotine or cocaine addict. The fMRI image of a cocaine addict who is high and a health freak doing exercise had an uncanny similarity from the perspective of neurochemistry and brain imaging.

Lack of exercise is a technology problem. Today we don't even walk to our neighbour to chat; we pick up the mobile instead. And then there is the lure of sitting back at home knowing that the world of entertainment is just a click away.

Some 150 minutes of exercise a week translates into 30 minutes a day for five days a week, or two 15 minute sessions of brisk walking. And that 15 minutes of apparent 'waste-of-time' would not only reduce your 'waist-in-time' but also reduce the chances of your developing high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, each by 30 per cent. A similar reduction of chance of depression and consequent improvement of self-confidence would be a bonus.

Powering your life and staying heart healthy is possible by getting hooked on to a new addiction - 'daily exercise'. All you need is to hold on till the initial hiccough is over - and then it would be bliss.

Q. All of the following statements can be inferred from the passage, EXCEPT that:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Ask any hardcore substance addict (try this only when they are sober) how his or her very first experience was, and they will for sure tell you it was not a very pleasant one. The violent cough of the first puff, the distaste of the first sip, the bitterness of the powder, hits them first; the feel-good factor and ecstasy that ends up in an unbreakable bond comes slowly, and much later. That's why we urge you to start the new addiction programme now, whatever be the initial hiccups.

Every patient is different, from shy and submissive to bold and aggressive; some are dead scared of injections while others go in for heart surgery with a smile. But the 'argumentative' types are special and the most difficult to handle; give them a piece of advice and they would be ready with an instant counter-argument. But it is these argumentative ones who teach the old doctors a new trick or two, by asking odd and embarrassing questions, forcing us to dig up old medical journals or try surfing the Net. That's exactly what happened when this young man asked me: ''I am not overweight, neither do I have diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease. Then why do you want me to exercise?'' The answer to that question is far from simple.

fMRI, or functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, is a system that can track blood circulation and show the intensity of activation of a localised area of the brain during a specific activity. Reading, for example, activates the occipital cortex, speaking lights up the speech area, while decision-making switches on the frontal cortex.

In a study researchers looked into the fMRI pattern in those who do regular exercise, and found that a 'C'-shaped structure, the caudate nucleus, a part of the basal ganglia, becomes highly active. This is caused by flooding of that area by a neurotransmitter called dopamine. This area is the reward area of the brain, and such activation makes the person feel happy. But what stumped the researchers was that the pattern of activation matched the fMRI imaging pattern of a nicotine or cocaine addict. The fMRI image of a cocaine addict who is high and a health freak doing exercise had an uncanny similarity from the perspective of neurochemistry and brain imaging.

Lack of exercise is a technology problem. Today we don't even walk to our neighbour to chat; we pick up the mobile instead. And then there is the lure of sitting back at home knowing that the world of entertainment is just a click away.

Some 150 minutes of exercise a week translates into 30 minutes a day for five days a week, or two 15 minute sessions of brisk walking. And that 15 minutes of apparent 'waste-of-time' would not only reduce your 'waist-in-time' but also reduce the chances of your developing high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, each by 30 per cent. A similar reduction of chance of depression and consequent improvement of self-confidence would be a bonus.

Powering your life and staying heart healthy is possible by getting hooked on to a new addiction - 'daily exercise'. All you need is to hold on till the initial hiccough is over - and then it would be bliss.

Q. It can be inferred from the author's mention of the phrase 'waste-of-time' that he believes

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

Ask any hardcore substance addict (try this only when they are sober) how his or her very first experience was, and they will for sure tell you it was not a very pleasant one. The violent cough of the first puff, the distaste of the first sip, the bitterness of the powder, hits them first; the feel-good factor and ecstasy that ends up in an unbreakable bond comes slowly, and much later. That's why we urge you to start the new addiction programme now, whatever be the initial hiccups.

Every patient is different, from shy and submissive to bold and aggressive; some are dead scared of injections while others go in for heart surgery with a smile. But the 'argumentative' types are special and the most difficult to handle; give them a piece of advice and they would be ready with an instant counter-argument. But it is these argumentative ones who teach the old doctors a new trick or two, by asking odd and embarrassing questions, forcing us to dig up old medical journals or try surfing the Net. That's exactly what happened when this young man asked me: ''I am not overweight, neither do I have diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease. Then why do you want me to exercise?'' The answer to that question is far from simple.

fMRI, or functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, is a system that can track blood circulation and show the intensity of activation of a localised area of the brain during a specific activity. Reading, for example, activates the occipital cortex, speaking lights up the speech area, while decision-making switches on the frontal cortex.

In a study researchers looked into the fMRI pattern in those who do regular exercise, and found that a 'C'-shaped structure, the caudate nucleus, a part of the basal ganglia, becomes highly active. This is caused by flooding of that area by a neurotransmitter called dopamine. This area is the reward area of the brain, and such activation makes the person feel happy. They also discovered that exercise released a hormone called BDNF (Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor) and endorphins, which resulted in such activation. While BDNF neutralised stress, endorphins took away the pain and fatigue of the exercise. But what stumped the researchers was that the pattern of activation matched the fMRI imaging pattern of a nicotine or cocaine addict. The fMRI image of a cocaine addict who is high and a health freak doing exercise had an uncanny similarity from the perspective of neurochemistry and brain imaging.

Lack of exercise is a technology problem. Today we don't even walk to our neighbour to chat; we pick up the mobile instead. And then there is the lure of sitting back at home knowing that the world of entertainment is just a click away, right in front of us, in our bedroom on LCD TV in high definition.

Some 150 minutes of exercise a week translates into 30 minutes a day for five days a week, which you can split it up into two 15 minute sessions of brisk walking. And that 15 minutes of apparent 'waste-of-time' would not only reduce your 'waist-in-time' but also reduce the chances of your developing high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, each by 30 per cent. A similar reduction of chance of depression and consequent improvement of self-confidence would be a bonus. For the eight-to-five creatures, who claim to be too busy, we advise them to walk or cycle to office.

The theme of World Heart Day, which fell last week on September 29, was, 'power your life' and stay heart healthy. You can do that by getting hooked on to a new addiction - 'daily exercise'. All you need is to hold on till the initial hiccough is over - and then it would be bliss. No legal restrictions, side-effects or withdrawal problems.

Q. According to the passage, which of the following revelations was rather surprising?

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

Beliefs in witchcraft in the generic sense are conspicuous in most small-scale communities where interaction is based upon personal relationships that tend to be life-long and difficult to break. In such societies belief in witches makes it possible for misfortunes to be explained in terms of disturbed social relationships; and the threat either of being accused of witchcraft or of being attacked by witches may well be a source of social control, making people more circumspect about their conduct toward others. Witches who are blamed for misfortunes, while visit near kinsmen and neighbours, are conceived of as inhuman and beyond the pale of decent society. They are, thus, convenient scapegoats who are blamed for events otherwise inexplicable in terms of the limited empirical knowledge prevailing in a society with a poorly developed technology - e.g., events such as sudden death or persistent illness or even accidents.

This explanatory function of witchcraft is widespread. So too are some of the details of the witch's believed habits and techniques, such as operating at night flying through the air on broomsticks or saucer shaped winnowing baskets.

The inherent disharmonies in the social system are cloaked under an insistence that there is harmony in the values of the society, and the surface disturbances that they cause are attributed to the wickedness of individuals. This is why the witch and sorcerer become the villains of the society's morality plays, the ones to whom the most inhuman crimes and characteristics are attributed. So numerous and so revolting are the believed practices of witches that to accuse anyone of witchcraft is a condensed way of charging him with a long list of the foulest crimes - and much the same may be said of sorcery, except that the alleged sorcerer might find some room for defence in the ambiguity as to when the use of destructive magic is legitimate and when it is to be regarded as sorcery.

Because accusations of witchcraft, if they are successful, are devastating attacks on reputation, they punctuate the micro-political processes relating to many forms of competition for some scarce status, power, resource, or personal affiliation. The believed victim of witchcraft or sorcery may also sometimes be regarded as getting his just deserts if he has, by tactless folly, incurred the wrath of dangerous, powerful persons in the community.

Because in such belief systems the transgressors of a society's ideals are depicted with dramatic disapproval, witchcraft and sorcery are usually powerful brakes upon social change. In many preliterate societies in modem times it is often those who have progressed economically and educationally who are most obsessed by fears of attack by witches and sorcerers or of accusation of employing witchcraft or sorcery. This is because they find themselves either out of line in social orders that economically at least are equalitarian or with a new-found status that lacks a niche in the traditional hierarchy.

On the other hand, belief in witchcraft may, under certain circumstances, have the effect of accelerating social change; e.g., by facilitating the rupture of close relationships that have become redundant but are difficult to break off in such a situation an accusation of witchcraft has the effect of making a public issue out of what started as a private quarrel.

Q. According to the author, witches are blamed unnecessarily and made to bear misdeeds of others in small scale communities because

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

Beliefs in witchcraft in the generic sense are conspicuous in most small-scale communities where interaction is based upon personal relationships that tend to be life-long and difficult to break. In such societies belief in witches makes it possible for misfortunes to be explained in terms of disturbed social relationships; and the threat either of being accused of witchcraft or of being attacked by witches may well be a source of social control, making people more circumspect about their conduct toward others. Witches who are blamed for misfortunes, while visit near kinsmen and neighbours, are conceived of as inhuman and beyond the pale of decent society. They are, thus, convenient scapegoats who are blamed for events otherwise inexplicable in terms of the limited empirical knowledge prevailing in a society with a poorly developed technology - e.g., events such as sudden death or persistent illness or even accidents.

This explanatory function of witchcraft is widespread. So too are some of the details of the witch's believed habits and techniques, such as operating at night flying through the air on broomsticks or saucer shaped winnowing baskets.

The inherent disharmonies in the social system are cloaked under an insistence that there is harmony in the values of the society, and the surface disturbances that they cause are attributed to the wickedness of individuals. This is why the witch and sorcerer become the villains of the society's morality plays, the ones to whom the most inhuman crimes and characteristics are attributed. So numerous and so revolting are the believed practices of witches that to accuse anyone of witchcraft is a condensed way of charging him with a long list of the foulest crimes - and much the same may be said of sorcery, except that the alleged sorcerer might find some room for defence in the ambiguity as to when the use of destructive magic is legitimate and when it is to be regarded as sorcery.

Because accusations of witchcraft, if they are successful, are devastating attacks on reputation, they punctuate the micro-political processes relating to many forms of competition for some scarce status, power, resource, or personal affiliation. The believed victim of witchcraft or sorcery may also sometimes be regarded as getting his just deserts if he has, by tactless folly, incurred the wrath of dangerous, powerful persons in the community.

Because in such belief systems the transgressors of a society's ideals are depicted with dramatic disapproval, witchcraft and sorcery are usually powerful brakes upon social change. In many preliterate societies in modem times it is often those who have progressed economically and educationally who are most obsessed by fears of attack by witches and sorcerers or of accusation of employing witchcraft or sorcery. This is because they find themselves either out of line in social orders that economically at least are equalitarian or with a new-found status that lacks a niche in the traditional hierarchy.

On the other hand, belief in witchcraft may, under certain circumstances, have the effect of accelerating social change; e.g., by facilitating the rupture of close relationships that have become redundant but are difficult to break off in such a situation an accusation of witchcraft has the effect of making a public issue out of what started as a private quarrel.

Q. The author asserts that belief in witchcraft, by helping to break redundant close relationships, can

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

Beliefs in witchcraft in the generic sense are conspicuous in most small-scale communities where interaction is based upon personal relationships that tend to be life-long and difficult to break. In such societies belief in witches makes it possible for misfortunes to be explained in terms of disturbed social relationships; and the threat either of being accused of witchcraft or of being attacked by witches may well be a source of social control, making people more circumspect about their conduct toward others. Witches who are blamed for misfortunes, while visit near kinsmen and neighbours, are conceived of as inhuman and beyond the pale of decent society. They are, thus, convenient scapegoats who are blamed for events otherwise inexplicable in terms of the limited empirical knowledge prevailing in a society with a poorly developed technology - e.g., events such as sudden death or persistent illness or even accidents.

This explanatory function of witchcraft is widespread. So too are some of the details of the witch's believed habits and techniques, such as operating at night flying through the air on broomsticks or saucer shaped winnowing baskets.

The inherent disharmonies in the social system are cloaked under an insistence that there is harmony in the values of the society, and the surface disturbances that they cause are attributed to the wickedness of individuals. This is why the witch and sorcerer become the villains of the society's morality plays, the ones to whom the most inhuman crimes and characteristics are attributed. So numerous and so revolting are the believed practices of witches that to accuse anyone of witchcraft is a condensed way of charging him with a long list of the foulest crimes - and much the same may be said of sorcery, except that the alleged sorcerer might find some room for defence in the ambiguity as to when the use of destructive magic is legitimate and when it is to be regarded as sorcery.

Because accusations of witchcraft, if they are successful, are devastating attacks on reputation, they punctuate the micro-political processes relating to many forms of competition for some scarce status, power, resource, or personal affiliation. The believed victim of witchcraft or sorcery may also sometimes be regarded as getting his just deserts if he has, by tactless folly, incurred the wrath of dangerous, powerful persons in the community.

Because in such belief systems the transgressors of a society's ideals are depicted with dramatic disapproval, witchcraft and sorcery are usually powerful brakes upon social change. In many preliterate societies in modem times it is often those who have progressed economically and educationally who are most obsessed by fears of attack by witches and sorcerers or of accusation of employing witchcraft or sorcery. This is because they find themselves either out of line in social orders that economically at least are equalitarian or with a new-found status that lacks a niche in the traditional hierarchy.

On the other hand, belief in witchcraft may, under certain circumstances, have the effect of accelerating social change; e.g., by facilitating the rupture of close relationships that have become redundant but are difficult to break off in such a situation an accusation of witchcraft has the effect of making a public issue out of what started as a private quarrel.

Q. According to the author, an alleged sorcerer is sometimes better off when compared to a witch as

Directions: The passage below is followed by a question based on its content. Answer the question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the passage.

Beliefs in witchcraft in the generic sense are conspicuous in most small-scale communities where interaction is based upon personal relationships that tend to be life-long and difficult to break. In such societies belief in witches makes it possible for misfortunes to be explained in terms of disturbed social relationships; and the threat either of being accused of witchcraft or of being attacked by witches may well be a source of social control, making people more circumspect about their conduct toward others. Witches who are blamed for misfortunes, while visit near kinsmen and neighbours, are conceived of as inhuman and beyond the pale of decent society. They are, thus, convenient scapegoats who are blamed for events otherwise inexplicable in terms of the limited empirical knowledge prevailing in a society with a poorly developed technology - e.g., events such as sudden death or persistent illness or even accidents.

This explanatory function of witchcraft is widespread. So too are some of the details of the witch's believed habits and techniques, such as operating at night flying through the air on broomsticks or saucer shaped winnowing baskets.

The inherent disharmonies in the social system are cloaked under an insistence that there is harmony in the values of the society, and the surface disturbances that they cause are attributed to the wickedness of individuals. This is why the witch and sorcerer become the villains of the society's morality plays, the ones to whom the most inhuman crimes and characteristics are attributed. So numerous and so revolting are the believed practices of witches that to accuse anyone of witchcraft is a condensed way of charging him with a long list of the foulest crimes - and much the same may be said of sorcery, except that the alleged sorcerer might find some room for defence in the ambiguity as to when the use of destructive magic is legitimate and when it is to be regarded as sorcery.

Because accusations of witchcraft, if they are successful, are devastating attacks on reputation, they punctuate the micro-political processes relating to many forms of competition for some scarce status, power, resource, or personal affiliation. The believed victim of witchcraft or sorcery may also sometimes be regarded as getting his just deserts if he has, by tactless folly, incurred the wrath of dangerous, powerful persons in the community.

Because in such belief systems the transgressors of a society's ideals are depicted with dramatic disapproval, witchcraft and sorcery are usually powerful brakes upon social change. In many preliterate societies in modem times it is often those who have progressed economically and educationally who are most obsessed by fears of attack by witches and sorcerers or of accusation of employing witchcraft or sorcery. This is because they find themselves either out of line in social orders that economically at least are equalitarian or with a new-found status that lacks a niche in the traditional hierarchy.

On the other hand, belief in witchcraft may, under certain circumstances, have the effect of accelerating social change; e.g., by facilitating the rupture of close relationships that have become redundant but are difficult to break off in such a situation an accusation of witchcraft has the effect of making a public issue out of what started as a private quarrel.

Q. According to the author, successful accusation of witchcraft can prove to be disastrous on reputation when

Directions: Answer the question based on the following passage:

The famous gorilla experiment conducted by Harvard University when a woman dressed in a gorilla suit ambled across the floor thumping her chest, but 50 % of the audience didn't notice. The study shows we often err when it comes to concentration and perception. Humans have a limited capacity for attention which in turn means that we have a limited capacity to process information at any given point of time.

When we open our eyes, the whole image gets projected on the retina, but only selective parts of the image are sensed by the brain. This is because as the amount of information in the image was too great to be processed, the brain selectively puts its attention on the most important aspects. Scientists have found that highly prominent events may go unnoticed.

Researchers now recognize a phenomenon known as "change blindness", which means that people often fail to detect changes in their field of vision, so long that the change takes place during an eye movement or when the view is somehow interrupted. It has been discovered that our brain tries to construct a meaningful whole out of stimuli that fits in with the scenario of its interest and is capable of discarding majority of other information. This fact can be easily explained by observing a child play the game "spot the difference". On the first look the child finds the pictures to be similar. Only after careful attention, does he find the differences. The present decade has seen a lot of research into this field. The questions that the scientists are trying to answer are: What is the amount of visual input a brain can consciously and unconsciously encode?

Why do some objects come in the field of observation and not others? What happens to information that is subconsciously perceived?

Arien Mack and Irvin Rock also conducted many experiments and co-authored a book "Inattentional Blindness" in 1998. One of their experiments was very simple. They asked the subjects to observe a cross on the computer screen. The subjects were repetitively asked to judge which arm of the cross was longer. They were in a way made to concentrate on the cross. After some time, unrepentantly, another brightly coloured object was inserted in their field of vision. The researchers reported that the participants often failed to notice the unexpected object on the screen, even when it appeared in the middle of their line of vision. The study gave a conclusive proof that there exists a wide gulf between perception and attention. Some psychologists are of the view that intentional blindness may be in some way related to selective memory instead of selective perception. The cause of the 'intentional amnesia' may be organic, functional or circumstantial.

Harvard university researchers have concluded that "we consciously see far less of our world than we think we do. We might well encode much of our visual world without awareness." We believe that we generally see what is in front of us and by basically looking. But looking and seeing are two different events. It has been observed that we look without seeing during moments of intense concentration. We have all observed that our eyes may be open, the images form on the retina, but still we have limited perception. We all remember these moments of blurred visuals and they come usually when either we are in deep thoughts or involved in an interesting conversation.

Q. Which of the following statements can be directly inferred from the passage about "Inattentional blindness"?

Directions: Answer the question based on the following passage:

The famous gorilla experiment conducted by Harvard University when a woman dressed in a gorilla suit ambled across the floor thumping her chest, but 50 % of the audience didn't notice. The study shows we often err when it comes to concentration and perception. Humans have a limited capacity for attention which in turn means that we have a limited capacity to process information at any given point of time.

When we open our eyes, the whole image gets projected on the retina, but only selective parts of the image are sensed by the brain. This is because as the amount of information in the image was too great to be processed, the brain selectively puts its attention on the most important aspects. Scientists have found that highly prominent events may go unnoticed.

Researchers now recognize a phenomenon known as "change blindness", which means that people often fail to detect changes in their field of vision, so long that the change takes place during an eye movement or when the view is somehow interrupted. It has been discovered that our brain tries to construct a meaningful whole out of stimuli that fits in with the scenario of its interest and is capable of discarding majority of other information. This fact can be easily explained by observing a child play the game "spot the difference". On the first look the child finds the pictures to be similar. Only after careful attention, does he find the differences. The present decade has seen a lot of research into this field. The questions that the scientists are trying to answer are: What is the amount of visual input a brain can consciously and unconsciously encode?

Why do some objects come in the field of observation and not others? What happens to information that is subconsciously perceived?

Arien Mack and Irvin Rock also conducted many experiments and co-authored a book "Inattentional Blindness" in 1998. One of their experiments was very simple. They asked the subjects to observe a cross on the computer screen. The subjects were repetitively asked to judge which arm of the cross was longer. They were in a way made to concentrate on the cross. After some time, unrepentantly, another brightly coloured object was inserted in their field of vision. The researchers reported that the participants often failed to notice the unexpected object on the screen, even when it appeared in the middle of their line of vision. The study gave a conclusive proof that there exists a wide gulf between perception and attention. Some psychologists are of the view that intentional blindness may be in some way related to selective memory instead of selective perception. The cause of the 'intentional amnesia' may be organic, functional or circumstantial.

Harvard university researchers have concluded that "we consciously see far less of our world than we think we do. We might well encode much of our visual world without awareness." We believe that we generally see what is in front of us and by basically looking. But looking and seeing are two different events. It has been observed that we look without seeing during moments of intense concentration. We have all observed that our eyes may be open, the images form on the retina, but still we have limited perception. We all remember these moments of blurred visuals and they come usually when either we are in deep thoughts or involved in an interesting conversation.

Q. The primary purpose of the passage is

Directions: Answer the question based on the following passage:

The famous gorilla experiment conducted by Harvard University when a woman dressed in a gorilla suit ambled across the floor thumping her chest, but 50 % of the audience didn't notice. The study shows we often err when it comes to concentration and perception. Humans have a limited capacity for attention which in turn means that we have a limited capacity to process information at any given point of time.

When we open our eyes, the whole image gets projected on the retina, but only selective parts of the image are sensed by the brain. This is because as the amount of information in the image was too great to be processed, the brain selectively puts its attention on the most important aspects. Scientists have found that highly prominent events may go unnoticed.

Researchers now recognize a phenomenon known as "change blindness", which means that people often fail to detect changes in their field of vision, so long that the change takes place during an eye movement or when the view is somehow interrupted. It has been discovered that our brain tries to construct a meaningful whole out of stimuli that fits in with the scenario of its interest and is capable of discarding majority of other information. This fact can be easily explained by observing a child play the game "spot the difference". On the first look the child finds the pictures to be similar. Only after careful attention, does he find the differences. The present decade has seen a lot of research into this field. The questions that the scientists are trying to answer are: What is the amount of visual input a brain can consciously and unconsciously encode?

Why do some objects come in the field of observation and not others? What happens to information that is subconsciously perceived?

Arien Mack and Irvin Rock also conducted many experiments and co-authored a book "Inattentional Blindness" in 1998. One of their experiments was very simple. They asked the subjects to observe a cross on the computer screen. The subjects were repetitively asked to judge which arm of the cross was longer. They were in a way made to concentrate on the cross. After some time, unrepentantly, another brightly coloured object was inserted in their field of vision. The researchers reported that the participants often failed to notice the unexpected object on the screen, even when it appeared in the middle of their line of vision. The study gave a conclusive proof that there exists a wide gulf between perception and attention. Some psychologists are of the view that intentional blindness may be in some way related to selective memory instead of selective perception. The cause of the 'intentional amnesia' may be organic, functional or circumstantial.

Harvard university researchers have concluded that "we consciously see far less of our world than we think we do. We might well encode much of our visual world without awareness." We believe that we generally see what is in front of us and by basically looking. But looking and seeing are two different events. It has been observed that we look without seeing during moments of intense concentration. We have all observed that our eyes may be open, the images form on the retina, but still we have limited perception. We all remember these moments of blurred visuals and they come usually when either we are in deep thoughts or involved in an interesting conversation.

Q. The passage answers all the below given questions, except:

Directions: Answer the question based on the following passage:

The famous gorilla experiment conducted by Harvard University when a woman dressed in a gorilla suit ambled across the floor thumping her chest, but 50 % of the audience didn't notice. The study shows we often err when it comes to concentration and perception. Humans have a limited capacity for attention which in turn means that we have a limited capacity to process information at any given point of time.

When we open our eyes, the whole image gets projected on the retina, but only selective parts of the image are sensed by the brain. This is because as the amount of information in the image was too great to be processed, the brain selectively puts its attention on the most important aspects. Scientists have found that highly prominent events may go unnoticed.

Researchers now recognize a phenomenon known as "change blindness", which means that people often fail to detect changes in their field of vision, so long that the change takes place during an eye movement or when the view is somehow interrupted. It has been discovered that our brain tries to construct a meaningful whole out of stimuli that fits in with the scenario of its interest and is capable of discarding majority of other information. This fact can be easily explained by observing a child play the game "spot the difference". On the first look the child finds the pictures to be similar. Only after careful attention, does he find the differences. The present decade has seen a lot of research into this field. The questions that the scientists are trying to answer are: What is the amount of visual input a brain can consciously and unconsciously encode?

Why do some objects come in the field of observation and not others? What happens to information that is subconsciously perceived?

Arien Mack and Irvin Rock also conducted many experiments and co-authored a book "Inattentional Blindness" in 1998. One of their experiments was very simple. They asked the subjects to observe a cross on the computer screen. The subjects were repetitively asked to judge which arm of the cross was longer. They were in a way made to concentrate on the cross. After some time, unrepentantly, another brightly coloured object was inserted in their field of vision. The researchers reported that the participants often failed to notice the unexpected object on the screen, even when it appeared in the middle of their line of vision. The study gave a conclusive proof that there exists a wide gulf between perception and attention. Some psychologists are of the view that intentional blindness may be in some way related to selective memory instead of selective perception. The cause of the 'intentional amnesia' may be organic, functional or circumstantial.

Harvard university researchers have concluded that "we consciously see far less of our world than we think we do. We might well encode much of our visual world without awareness." We believe that we generally see what is in front of us and by basically looking. But looking and seeing are two different events. It has been observed that we look without seeing during moments of intense concentration. We have all observed that our eyes may be open, the images form on the retina, but still we have limited perception. We all remember these moments of blurred visuals and they come usually when either we are in deep thoughts or involved in an interesting conversation.

Q. The role of the last paragraph of the passage is to

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: For in India, turmeric is much more than an unassuming kitchen spice, assuming a significant place in culture.

Paragraph: In the Tamil harvest festival of Pongal in mid-January, fresh turmeric leaves and roots are tied to the mouth of the ceremonial pot, indicating abundance. ___(1)___. Among many Hindu communities, turmeric is used in festive occasions like weddings as a marker of fertility and prosperity. The pre-wedding haldi ceremony, for instance, involves family elders applying turmeric paste on the faces of the bride and the groom in a blessing-meets-beauty ritual. ___(2)___. The mangalsutra is often a thick woven thread dipped in turmeric water; and even now, clothes worn on auspicious occasions (including weddings) have a touch of turmeric powder in some corner. ___(3)___. Also, Indian women have always added a pinch of turmeric to their homemade face packs, believing that it leaves the skin clear and glowing. ___(4)___.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

A dream pictures earthly beauty to our eyes in a truly heavenly splendour and clothes dignity with the highest majesty. It shows us everyday fears in the ghastliest shape and turns our amusement into jokes of indescribable pungency. And sometimes when we are awake and still under the full impact of an experience like one of these, we cannot but feel that never in our life has the real world offered us its equal.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. Bombyx Mori, the domestic silk moths, are an unusual species that have been so selectively bred they are entirely dependent on humans for their survival.

2. The dependence of the silk trade on mulberry trees makes them highly prized plants, so research into protecting and optimising their productivity is critical for the future of the silk industry.

3. They cannot fly, and swathes of fresh mulberry leaves must be brought to sustain their ravenous larvae so they can form their precious, and economically valuable, silk cocoons.

4. Mulberry trees have the unique status of being the only food that Mulberry silkworms will feast on.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Helvetius, amongst many false positions and licentious reveries, observes with much justice, that the education of man begins at his birth, and is carried on during the whole course of his life. The lowest mechanic, though he may not have distinct and accurate science, has yet such a store of geography, of natural history, of mechanics, and other parts of knowledge, that were his mind to be emptied of it, the wretched vacancy would amaze us.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

One principle of life drives man. This principle is physical sensibility. What produces in him this sensibility? A feeling of love for pleasure, and of hatred for pain? It is from both these feelings joined together in man and always present in his mind that is formed what one calls in him the feeling of self-love. This self-love engenders the desire for happiness; the desire for happiness that for power; and it is this latter that in turn brings forth envy, avarice, ambition and generally all the artificial passions, which, under different names, are only a disguised love of power in us and applied to the various means of obtaining it.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. Such experiments which are considered 'crucial' are important; they deliver a decisive answer to a question.

2. Usually, an experiment is considered crucial when it confirms a hypothesis among alternative competitors, and thus settles a dispute.

3. It is from this ability to deliver a decisive answer to the question of how DNA replicates that the Meselson-Stahl experiment can be considered to derive its beauty.

4. One of the reasons why this experiment is celebrated in science is that it is an example of an experimentum crucis, or a 'crucial experiment'.

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer.

1. This implies a relationship of mutual responsibility between human beings and nature.

2. The biblical texts are to be read in their context, with an appropriate hermeneutic, recognizing that they tell us to 'till and keep' the garden of the world.

3. Although it is true that we Christians have at times incorrectly interpreted the Scriptures, we must reject the notion that we being given dominion over the Earth justifies absolute domination over other creatures.

4. 'Tilling' refers to cultivating, ploughing or working, while 'keeping' means caring, protecting, overseeing and preserving.

Directions: There is a sentence that is missing in the paragraph below. Look at the paragraph and decide in which blank (option 1, 2, 3, or 4) the following sentence would best fit.

Sentence: But this daunting reorganisation, or breakup, could also provide banks with a huge opportunity: higher margins, new revenue streams, and loftier valuations.

Paragraph: Banking is facing a future marked by restructuring. ___(1)___. But we also believe that banks that successfully manage this transition will become bigger and more profitable and grow faster. ___(2)___. In the next era, banks can realign to compete in new arenas, organised around distinct customer needs. ___(3)___. These arenas will expand far beyond the current definition of financial services, and they will also be hotly contested by a wide range of tech giants, tech start-ups, and other non-banks. ___(4)___. Ambitious banks can break free from stagnant valuations, thrive, and grow if they are willing to embrace the platforms of the future and make a few strategic, informed big bets.

Directions: Shivani is a private employee and she earns a fixed salary every month. She also pays tax. The tax is always calculated after the deductions if there exists any kind of deductions. The deductions are as follows:

(i) Shivani donates 40,000 in an orphanage which has 100% exemption.

(ii) The standard deductions is one - third of the annual salary.

After allowing the deductions, the remaining income is taxed, which is so called tax before rebate. The rate of the tax on her taxable income is 20%. As she saves 35,000 rupees towards the contributory provident fund and 25,000 towards public provident fund, 20% of each can be deducted from the tax calculated before the rebate. This is the tax after rebate.

There is a surcharge to be imposed and it is imposed after the rebate and the total amount to be paid is calculated. The surcharge is 5% on the tax after the rebate which amounts to 5000 rupees.

Q. If the savings in the contributory provident fund and the public provident fund fetches 10% interest and the tax on the interest earned is 50/3% and the tax paid by her includes the tax due to this interest, then what will be the difference between the salary of Shivani in this case and her salary calculated before without considering the tax on the interest, assuming all the other things remain the same.

Directions: Shivani is a private employee and she earns a fixed salary every month. She also pays tax. The tax is always calculated after the deductions if there exists any kind of deductions. The deductions are as follows:

(i) Shivani donates 40,000 in an orphanage which has 100% exemption.

(ii) The standard deductions is one - third of the annual salary.

After allowing the deductions, the remaining income is taxed, which is so called tax before rebate. The rate of the tax on her taxable income is 20%. As she saves 35,000 rupees towards the contributory provident fund and 25,000 towards public provident fund, 20% of each can be deducted from the tax calculated before the rebate. This is the tax after rebate.

There is a surcharge to be imposed and it is imposed after the rebate and the total amount to be paid is calculated. The surcharge is 5% on the tax after the rebate which amounts to 5000 rupees.

Q. The monthly income of Shivani in rupees?

Directions: Shivani is a private employee and she earns a fixed salary every month. She also pays tax. The tax is always calculated after the deductions if there exists any kind of deductions. The deductions are as follows:

(i) Shivani donates 40,000 in an orphanage which has 100% exemption.

(ii) The standard deductions is one - third of the annual salary.

After allowing the deductions, the remaining income is taxed, which is so called tax before rebate. The rate of the tax on her taxable income is 20%. As she saves 35,000 rupees towards the contributory provident fund and 25,000 towards public provident fund, 20% of each can be deducted from the tax calculated before the rebate. This is the tax after rebate.

There is a surcharge to be imposed and it is imposed after the rebate and the total amount to be paid is calculated. The surcharge is 5% on the tax after the rebate which amounts to 5000 rupees.

Q. If Shivani is a senior citizen and she is eligible for an additional rebate of 20,000 which can be deducted from the tax before the rebate, then what will be the annual salary of Shivani in rupees if all the other things remained the same?

Directions: Shivani is a private employee and she earns a fixed salary every month. She also pays tax. The tax is always calculated after the deductions if there exists any kind of deductions. The deductions are as follows:

(i) Shivani donates 40,000 in an orphanage which has 100% exemption.

(ii) The standard deductions is one - third of the annual salary.

After allowing the deductions, the remaining income is taxed, which is so called tax before rebate. The rate of the tax on her taxable income is 20%. As she saves 35,000 rupees towards the contributory provident fund and 25,000 towards public provident fund, 20% of each can be deducted from the tax calculated before the rebate. This is the tax after rebate.

There is a surcharge to be imposed and it is imposed after the rebate and the total amount to be paid is calculated. The surcharge is 5% on the tax after the rebate which amounts to 5000 rupees.

Q. If the boss of the Shivani deducts 8000 rupees per month during the first eleven month of the financial year as taxes, then find the amount paid by her in the last month of the financial year as a percentage of her monthly income.

Directions: Read the following information and answer the questions that follow.

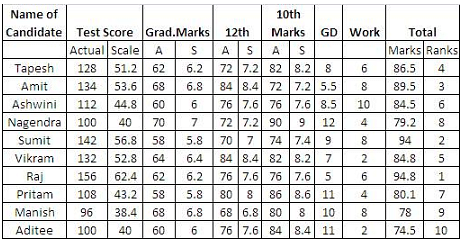

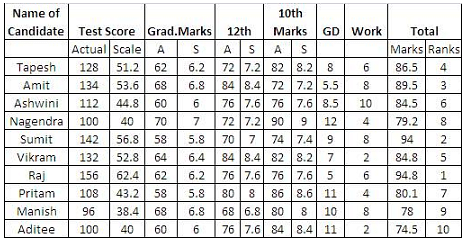

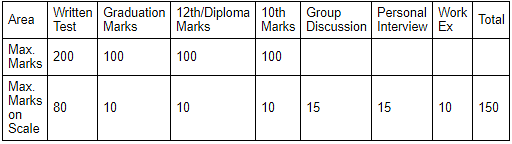

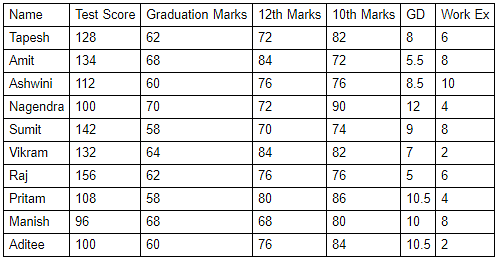

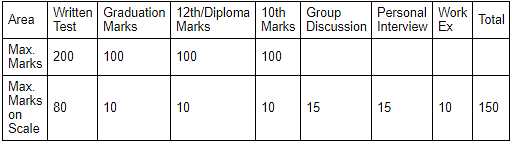

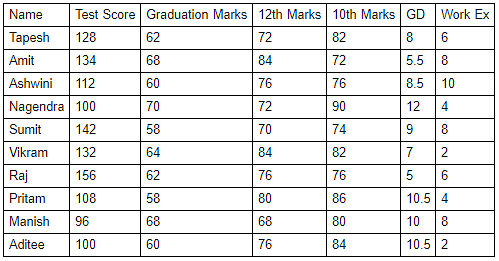

A school of management conducts its own test for its entrance procedure which is of 200 marks. However, academics and work experience details are considered with the marks obtained in group discussion and personal interview. After considering a candidate in all of these areas, a selection of a set of students is supposed to be made. The marking system is as follows:

The evaluation scale works as follows: A student scoring 200 marks in aptitude test will be given 80 marks on evaluation scale and an 80% in 10th exam will give a student 8 marks on evaluation scale.

Q. If Amit scores 8 marks in PI and is behind Raj, Tapesh and Sumit in total scores, then what can be the minimum total marks Sumit can have if these three students scored same marks in personal interview? (marks obtained in PI are integral).

Directions: Read the following information and answer the questions that follow.

A school of management conducts its own test for its entrance procedure which is of 200 marks. However, academics and work experience details are considered with the marks obtained in group discussion and personal interview. After considering a candidate in all of these areas, a selection of a set of students is supposed to be made. The marking system is as follows:

The evaluation scale works as follows: A student scoring 200 marks in aptitude test will be given 80 marks on evaluation scale and an 80% in 10th exam will give a student 8 marks on evaluation scale.

Q. Another institute uses the same exam scores and selects candidates after elimination. Every time the least scorer in written test, then in Graduation, then in 12th, then in 10th, then Work Experience and then GD is eliminated. Then how many would not make it to PI, if all of them are in one group?(Also, if there is a tie for the least score, then both are eliminated)