CAT Mock Test - 20 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test - 20

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Private philanthropists have helped propel some of the most important social-impact success stories of the past century: Virtually eradicating polio globally. Providing free and reduced-price lunches for all needy schoolchildren in the United States. Establishing a universal 911 service. Securing the right for same-sex couples to marry in the U.S. These efforts have transformed or saved hundreds of millions of lives. That we now take them for granted makes them no less astonishing: They were the inconceivable moon shots of their day before they were inevitable success stories in retrospect. Many of today's emerging large-scale philanthropists aspire to similarly audacious successes. They don't want to fund homeless shelters and food pantries; they want to end homelessness and hunger. Steady, linear progress isn't enough; they demand disruptive, catalytic, systemic change - and in short order. Even as society grapples with important questions about today's concentrations of wealth, many of the largest philanthropists feel the weight of responsibility that comes with their privilege. And the scale of their ambition, along with the wealth they are willing to give back to society, is breath taking.

But a growing number of these donors privately express great frustration. Despite having written big checks for years, they aren't seeing transformative successes for society: Think of philanthropic interventions to arrest climate change or improve U.S. public education, to cite just two examples. When faced with setbacks and public criticism, the best philanthropists re-examine their goals and approaches, including how they engage the communities they aspire to help in the decision-making process. But some retreat to seemingly safer donations to universities or art museums, while others withdraw from public giving altogether.

Audacious social change is incredibly challenging. Yet history shows that it can succeed. Unfortunately, success never results from a silver bullet; it takes collaboration, government engagement, and persistence over decades, among other things. The role of philanthropists in the historical success stories vary. By and large they underwrote the efforts of others. The hands-on work fell, as it does today, to NGO leaders, service providers, activists, and many others on the front lines of social change. The common thread in these success stories was that philanthropists acted as sources of flexible capital, identifying gaps left by others and directing their resources accordingly. Sometimes only minor support was enough to tip the scales. This framework does not constitute a simple or linear recipe.

Real change is highly complex and driven by many forces, luck and timing play important roles, and causality is impossible to prove. Still, we believe that if ambitious philanthropists apply the framework over the arc of a campaign, they may substantially increase the odds of achieving transformative change. There are some high-level reasons as to why so many efforts wither on the vine. Most of the these share four important patterns: Success took a long time - nearly 90% of the efforts spanned more than 20 years. It frequently entailed government cooperation - 80% required changes to government funding, policies, or actions. It often necessitated collaboration - nearly 75% involved active coordination among key actors across sectors. And at least 66% featured donors who made one or more philanthropic big bets - gifts of $10 million or more.

Unfortunately, these patterns go against the grain of much philanthropic practice today. Donors know conceptually that achieving widespread change can take a long time, even for the most important and straightforward ideas. The basic lifesaving practice of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities took 30 years to gain acceptance even after a leading medical journal published ironclad evidence in support of it. Yet philanthropists often fund grantees with the expectation that much more complex change can be achieved in just a handful of years. Wary of red tape and of being perceived as "too political," many donors have been unwilling to fund work that meaningfully engages with the U.S. government, despite the central role it plays and the trillions of dollars it spends addressing society's toughest problems. Furthermore, collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists meaningfully support or engage in it, even though most are frustrated with the inefficient proliferation of siloed change efforts. And finally, only a small fraction of donor gifts for social change are large enough to make a dent - although philanthropists routinely commit $20 million or more to infinitely simpler challenges, such as building a university library or a museum wing.

Q. What is the tone of the author in the last para of the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Private philanthropists have helped propel some of the most important social-impact success stories of the past century: Virtually eradicating polio globally. Providing free and reduced-price lunches for all needy schoolchildren in the United States. Establishing a universal 911 service. Securing the right for same-sex couples to marry in the U.S. These efforts have transformed or saved hundreds of millions of lives. That we now take them for granted makes them no less astonishing: They were the inconceivable moon shots of their day before they were inevitable success stories in retrospect. Many of today's emerging large-scale philanthropists aspire to similarly audacious successes. They don't want to fund homeless shelters and food pantries; they want to end homelessness and hunger. Steady, linear progress isn't enough; they demand disruptive, catalytic, systemic change - and in short order. Even as society grapples with important questions about today's concentrations of wealth, many of the largest philanthropists feel the weight of responsibility that comes with their privilege. And the scale of their ambition, along with the wealth they are willing to give back to society, is breath taking.

But a growing number of these donors privately express great frustration. Despite having written big checks for years, they aren't seeing transformative successes for society: Think of philanthropic interventions to arrest climate change or improve U.S. public education, to cite just two examples. When faced with setbacks and public criticism, the best philanthropists re-examine their goals and approaches, including how they engage the communities they aspire to help in the decision-making process. But some retreat to seemingly safer donations to universities or art museums, while others withdraw from public giving altogether.

Audacious social change is incredibly challenging. Yet history shows that it can succeed. Unfortunately, success never results from a silver bullet; it takes collaboration, government engagement, and persistence over decades, among other things. The role of philanthropists in the historical success stories vary. By and large they underwrote the efforts of others. The hands-on work fell, as it does today, to NGO leaders, service providers, activists, and many others on the front lines of social change. The common thread in these success stories was that philanthropists acted as sources of flexible capital, identifying gaps left by others and directing their resources accordingly. Sometimes only minor support was enough to tip the scales. This framework does not constitute a simple or linear recipe.

Real change is highly complex and driven by many forces, luck and timing play important roles, and causality is impossible to prove. Still, we believe that if ambitious philanthropists apply the framework over the arc of a campaign, they may substantially increase the odds of achieving transformative change. There are some high-level reasons as to why so many efforts wither on the vine. Most of the these share four important patterns: Success took a long time - nearly 90% of the efforts spanned more than 20 years. It frequently entailed government cooperation - 80% required changes to government funding, policies, or actions. It often necessitated collaboration - nearly 75% involved active coordination among key actors across sectors. And at least 66% featured donors who made one or more philanthropic big bets - gifts of $10 million or more.

Unfortunately, these patterns go against the grain of much philanthropic practice today. Donors know conceptually that achieving widespread change can take a long time, even for the most important and straightforward ideas. The basic lifesaving practice of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities took 30 years to gain acceptance even after a leading medical journal published ironclad evidence in support of it. Yet philanthropists often fund grantees with the expectation that much more complex change can be achieved in just a handful of years. Wary of red tape and of being perceived as "too political," many donors have been unwilling to fund work that meaningfully engages with the U.S. government, despite the central role it plays and the trillions of dollars it spends addressing society's toughest problems. Furthermore, collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists meaningfully support or engage in it, even though most are frustrated with the inefficient proliferation of siloed change efforts. And finally, only a small fraction of donor gifts for social change are large enough to make a dent - although philanthropists routinely commit $20 million or more to infinitely simpler challenges, such as building a university library or a museum wing.

Q. Which of the following instances could comply to the words of the author in the passage where he says that the philanthropists underwrote the efforts of others?

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Private philanthropists have helped propel some of the most important social-impact success stories of the past century: Virtually eradicating polio globally. Providing free and reduced-price lunches for all needy schoolchildren in the United States. Establishing a universal 911 service. Securing the right for same-sex couples to marry in the U.S. These efforts have transformed or saved hundreds of millions of lives. That we now take them for granted makes them no less astonishing: They were the inconceivable moon shots of their day before they were inevitable success stories in retrospect. Many of today's emerging large-scale philanthropists aspire to similarly audacious successes. They don't want to fund homeless shelters and food pantries; they want to end homelessness and hunger. Steady, linear progress isn't enough; they demand disruptive, catalytic, systemic change - and in short order. Even as society grapples with important questions about today's concentrations of wealth, many of the largest philanthropists feel the weight of responsibility that comes with their privilege. And the scale of their ambition, along with the wealth they are willing to give back to society, is breath taking.

But a growing number of these donors privately express great frustration. Despite having written big checks for years, they aren't seeing transformative successes for society: Think of philanthropic interventions to arrest climate change or improve U.S. public education, to cite just two examples. When faced with setbacks and public criticism, the best philanthropists re-examine their goals and approaches, including how they engage the communities they aspire to help in the decision-making process. But some retreat to seemingly safer donations to universities or art museums, while others withdraw from public giving altogether.

Audacious social change is incredibly challenging. Yet history shows that it can succeed. Unfortunately, success never results from a silver bullet; it takes collaboration, government engagement, and persistence over decades, among other things. The role of philanthropists in the historical success stories vary. By and large they underwrote the efforts of others. The hands-on work fell, as it does today, to NGO leaders, service providers, activists, and many others on the front lines of social change. The common thread in these success stories was that philanthropists acted as sources of flexible capital, identifying gaps left by others and directing their resources accordingly. Sometimes only minor support was enough to tip the scales. This framework does not constitute a simple or linear recipe.

Real change is highly complex and driven by many forces, luck and timing play important roles, and causality is impossible to prove. Still, we believe that if ambitious philanthropists apply the framework over the arc of a campaign, they may substantially increase the odds of achieving transformative change. There are some high-level reasons as to why so many efforts wither on the vine. Most of the these share four important patterns: Success took a long time - nearly 90% of the efforts spanned more than 20 years. It frequently entailed government cooperation - 80% required changes to government funding, policies, or actions. It often necessitated collaboration - nearly 75% involved active coordination among key actors across sectors. And at least 66% featured donors who made one or more philanthropic big bets - gifts of $10 million or more.

Unfortunately, these patterns go against the grain of much philanthropic practice today. Donors know conceptually that achieving widespread change can take a long time, even for the most important and straightforward ideas. The basic lifesaving practice of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities took 30 years to gain acceptance even after a leading medical journal published ironclad evidence in support of it. Yet philanthropists often fund grantees with the expectation that much more complex change can be achieved in just a handful of years. Wary of red tape and of being perceived as "too political," many donors have been unwilling to fund work that meaningfully engages with the U.S. government, despite the central role it plays and the trillions of dollars it spends addressing society's toughest problems. Furthermore, collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists meaningfully support or engage in it, even though most are frustrated with the inefficient proliferation of siloed change efforts. And finally, only a small fraction of donor gifts for social change are large enough to make a dent - although philanthropists routinely commit $20 million or more to infinitely simpler challenges, such as building a university library or a museum wing.

Q. Which of the following could be the reason(s) for the basic lifesaving practice of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities taking 30 years to gain acceptance even after the leading medical journal published strong evidence in support of it?

I. Even though evidence was given, the journal was not able to actively preach the importance of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities.

II. It was a substantial change in the normal practices that were being followed till the time, and so, acceptance of something this different and of this scale took time.

III. Some of the researches previously published in the said journal were later deemed false upon further investigations; hence, people were sceptical about adopting one of its advices again - the reason it took so much time.

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Private philanthropists have helped propel some of the most important social-impact success stories of the past century: Virtually eradicating polio globally. Providing free and reduced-price lunches for all needy schoolchildren in the United States. Establishing a universal 911 service. Securing the right for same-sex couples to marry in the U.S. These efforts have transformed or saved hundreds of millions of lives. That we now take them for granted makes them no less astonishing: They were the inconceivable moon shots of their day before they were inevitable success stories in retrospect. Many of today's emerging large-scale philanthropists aspire to similarly audacious successes. They don't want to fund homeless shelters and food pantries; they want to end homelessness and hunger. Steady, linear progress isn't enough; they demand disruptive, catalytic, systemic change - and in short order. Even as society grapples with important questions about today's concentrations of wealth, many of the largest philanthropists feel the weight of responsibility that comes with their privilege. And the scale of their ambition, along with the wealth they are willing to give back to society, is breath taking.

But a growing number of these donors privately express great frustration. Despite having written big checks for years, they aren't seeing transformative successes for society: Think of philanthropic interventions to arrest climate change or improve U.S. public education, to cite just two examples. When faced with setbacks and public criticism, the best philanthropists re-examine their goals and approaches, including how they engage the communities they aspire to help in the decision-making process. But some retreat to seemingly safer donations to universities or art museums, while others withdraw from public giving altogether.

Audacious social change is incredibly challenging. Yet history shows that it can succeed. Unfortunately, success never results from a silver bullet; it takes collaboration, government engagement, and persistence over decades, among other things. The role of philanthropists in the historical success stories vary. By and large they underwrote the efforts of others. The hands-on work fell, as it does today, to NGO leaders, service providers, activists, and many others on the front lines of social change. The common thread in these success stories was that philanthropists acted as sources of flexible capital, identifying gaps left by others and directing their resources accordingly. Sometimes only minor support was enough to tip the scales. This framework does not constitute a simple or linear recipe.

Real change is highly complex and driven by many forces, luck and timing play important roles, and causality is impossible to prove. Still, we believe that if ambitious philanthropists apply the framework over the arc of a campaign, they may substantially increase the odds of achieving transformative change. There are some high-level reasons as to why so many efforts wither on the vine. Most of the these share four important patterns: Success took a long time - nearly 90% of the efforts spanned more than 20 years. It frequently entailed government cooperation - 80% required changes to government funding, policies, or actions. It often necessitated collaboration - nearly 75% involved active coordination among key actors across sectors. And at least 66% featured donors who made one or more philanthropic big bets - gifts of $10 million or more.

Unfortunately, these patterns go against the grain of much philanthropic practice today. Donors know conceptually that achieving widespread change can take a long time, even for the most important and straightforward ideas. The basic lifesaving practice of hand washing and sterilizing surgical instruments and facilities took 30 years to gain acceptance even after a leading medical journal published ironclad evidence in support of it. Yet philanthropists often fund grantees with the expectation that much more complex change can be achieved in just a handful of years. Wary of red tape and of being perceived as "too political," many donors have been unwilling to fund work that meaningfully engages with the U.S. government, despite the central role it plays and the trillions of dollars it spends addressing society's toughest problems. Furthermore, collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists meaningfully support or engage in it, even though most are frustrated with the inefficient proliferation of siloed change efforts. And finally, only a small fraction of donor gifts for social change are large enough to make a dent - although philanthropists routinely commit $20 million or more to infinitely simpler challenges, such as building a university library or a museum wing.

Q. Which of the following could be the underlying idea(s) that the author wants to reflect from the passage?

I. The issues most deserving of investment today are different from those of past decades; what remains constant is the need for shared and dynamic problem definition, clear and winnable milestones, solutions built for scale, robust investments to drive and serve demand, and adaptive capacity among philanthropists and grantees alike.

II. At the highest level, the successful strategies that should be practiced run counter to prevailing funding practices. They included decades-long persistence, even when the pace of change felt slow; financial support for collaboration among key actors, even when it meant giving up some control; engagement with governments to influence funding and action, even in uncertain times; and big philanthropic bets that shifted power from the donor to the doers and beneficiaries.

III. For the types of social challenges targeted by audacious philanthropists and other change makers, adaptation informed by robust measurement is key and to fuel progress, funders need to make sure that both their attitudes and their funding reflect that reality.

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Children begin to learn values when they are very young, before they can reason effectively. Young children behave in ways that we would never accept in adults: they scream, throw food, take off their clothes in public, hit, scratch, bite, and generally make a ruckus. Moral education begins from the start, as parents correct these antisocial behaviours, and they usually do so by conditioning children's emotions. Parents threaten physical punishment ("Do you want a spanking?"), they withdraw love ("I'm not going to play with you anymore!"), ostracize ("Go to your room!"), deprive ("No dessert for you!"), and induce vicarious distress ("Look at the pain you've caused!"). Each of these methods causes the misbehaved child to experience a negative emotion and associate it with the punished behaviour. Children also learn by emotional osmosis. They see their parents' reactions to news broadcasts and storybooks. They hear hours of judgmental gossip about inconsiderate neighbours, unethical co-workers, disloyal friends, and the black sheep in the family.

Emotional conditioning and osmosis are not merely convenient tools for acquiring values: they are essential. Parents sometimes try to reason with their children, but moral reasoning only works by drawing attention to values that the child has already internalized through emotional conditioning. No amount of reasoning can engender a moral value, because all values are, at bottom, emotional attitudes. Recent research in psychology supports this conjecture. It seems that we decide whether something is wrong by introspecting our feelings: if an action makes us feel bad, we conclude that it is wrong. Consistent with this, people's moral judgments can be shifted by simply altering their emotional states.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues have shown that people make moral judgments even when they cannot provide any justification for them. For example, 80% of the American college students in Haidt's study said it's wrong for two adult siblings to have consensual sex with each other even if they use contraception and no one is harmed. And, in a study I ran, 100% of people agreed it would be wrong to sexually fondle an infant even if the infant was not physically harmed or traumatized. Our emotions confirm that such acts are wrong even if our usual justification for that conclusion (harm to the victim) is inapplicable.

If morals are emotionally based, then people who lack strong emotions should be blind to the moral domain. This prediction is borne out by psychopaths, who, it turns out, suffer from profound emotional deficits. Psychologist James Blair has shown that psychopaths treat moral rules as mere conventions. This suggests that emotions are necessary for making moral judgments. The judgment that something is morally wrong is an emotional response.

It doesn't follow that every emotional response is a moral judgment. Morality involves specific emotions. Research suggests that the main moral emotions are anger and disgust when an action is performed by another person, and guilt and shame when an action is performed by oneself. Arguably, one doesn't harbour a moral attitude towards something unless one is disposed to have both these self- and other-directed emotions. You may be disgusted by eating cow tongue, but unless you are a moral vegetarian, you wouldn't be ashamed of eating it.

In some cases, the moral emotions that get conditioned in childhood can be re-conditioned later in life. Someone who feels ashamed of a homosexual desire may subsequently feel ashamed about feeling ashamed. This person can be said to have an inculcated tendency to view homosexuality as immoral, but also a conviction that homosexuality is permissible, and the latter serves to curb the former over time.

In summary, moral judgments are based on emotions, and reasoning normally contributes only by helping us extrapolate from our basic values to novel cases. Reasoning can also lead us to discover that our basic values are culturally inculcated, and that might impel us to search for alternative values, but reason alone cannot tell us which values to adopt, nor can it instil new values.

Q. It can be understood that in the first paragraph, which of the following is the main purpose of the author?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Children begin to learn values when they are very young, before they can reason effectively. Young children behave in ways that we would never accept in adults: they scream, throw food, take off their clothes in public, hit, scratch, bite, and generally make a ruckus. Moral education begins from the start, as parents correct these antisocial behaviours, and they usually do so by conditioning children's emotions. Parents threaten physical punishment ("Do you want a spanking?"), they withdraw love ("I'm not going to play with you anymore!"), ostracize ("Go to your room!"), deprive ("No dessert for you!"), and induce vicarious distress ("Look at the pain you've caused!"). Each of these methods causes the misbehaved child to experience a negative emotion and associate it with the punished behaviour. Children also learn by emotional osmosis. They see their parents' reactions to news broadcasts and storybooks. They hear hours of judgmental gossip about inconsiderate neighbours, unethical co-workers, disloyal friends, and the black sheep in the family.

Emotional conditioning and osmosis are not merely convenient tools for acquiring values: they are essential. Parents sometimes try to reason with their children, but moral reasoning only works by drawing attention to values that the child has already internalized through emotional conditioning. No amount of reasoning can engender a moral value, because all values are, at bottom, emotional attitudes. Recent research in psychology supports this conjecture. It seems that we decide whether something is wrong by introspecting our feelings: if an action makes us feel bad, we conclude that it is wrong. Consistent with this, people's moral judgments can be shifted by simply altering their emotional states.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues have shown that people make moral judgments even when they cannot provide any justification for them. For example, 80% of the American college students in Haidt's study said it's wrong for two adult siblings to have consensual sex with each other even if they use contraception and no one is harmed. And, in a study I ran, 100% of people agreed it would be wrong to sexually fondle an infant even if the infant was not physically harmed or traumatized. Our emotions confirm that such acts are wrong even if our usual justification for that conclusion (harm to the victim) is inapplicable.

If morals are emotionally based, then people who lack strong emotions should be blind to the moral domain. This prediction is borne out by psychopaths, who, it turns out, suffer from profound emotional deficits. Psychologist James Blair has shown that psychopaths treat moral rules as mere conventions. This suggests that emotions are necessary for making moral judgments. The judgment that something is morally wrong is an emotional response.

It doesn't follow that every emotional response is a moral judgment. Morality involves specific emotions. Research suggests that the main moral emotions are anger and disgust when an action is performed by another person, and guilt and shame when an action is performed by oneself. Arguably, one doesn't harbour a moral attitude towards something unless one is disposed to have both these self- and other-directed emotions. You may be disgusted by eating cow tongue, but unless you are a moral vegetarian, you wouldn't be ashamed of eating it.

In some cases, the moral emotions that get conditioned in childhood can be re-conditioned later in life. Someone who feels ashamed of a homosexual desire may subsequently feel ashamed about feeling ashamed. This person can be said to have an inculcated tendency to view homosexuality as immoral, but also a conviction that homosexuality is permissible, and the latter serves to curb the former over time.

In summary, moral judgments are based on emotions, and reasoning normally contributes only by helping us extrapolate from our basic values to novel cases. Reasoning can also lead us to discover that our basic values are culturally inculcated, and that might impel us to search for alternative values, but reason alone cannot tell us which values to adopt, nor can it instil new values.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that the author has used which of the following examples to strengthen his argument that emotional reactions are crucial for the forming of moral judgements?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Children begin to learn values when they are very young, before they can reason effectively. Young children behave in ways that we would never accept in adults: they scream, throw food, take off their clothes in public, hit, scratch, bite, and generally make a ruckus. Moral education begins from the start, as parents correct these antisocial behaviours, and they usually do so by conditioning children's emotions. Parents threaten physical punishment ("Do you want a spanking?"), they withdraw love ("I'm not going to play with you anymore!"), ostracize ("Go to your room!"), deprive ("No dessert for you!"), and induce vicarious distress ("Look at the pain you've caused!"). Each of these methods causes the misbehaved child to experience a negative emotion and associate it with the punished behaviour. Children also learn by emotional osmosis. They see their parents' reactions to news broadcasts and storybooks. They hear hours of judgmental gossip about inconsiderate neighbours, unethical co-workers, disloyal friends, and the black sheep in the family.

Emotional conditioning and osmosis are not merely convenient tools for acquiring values: they are essential. Parents sometimes try to reason with their children, but moral reasoning only works by drawing attention to values that the child has already internalized through emotional conditioning. No amount of reasoning can engender a moral value, because all values are, at bottom, emotional attitudes. Recent research in psychology supports this conjecture. It seems that we decide whether something is wrong by introspecting our feelings: if an action makes us feel bad, we conclude that it is wrong. Consistent with this, people's moral judgments can be shifted by simply altering their emotional states.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues have shown that people make moral judgments even when they cannot provide any justification for them. For example, 80% of the American college students in Haidt's study said it's wrong for two adult siblings to have consensual sex with each other even if they use contraception and no one is harmed. And, in a study I ran, 100% of people agreed it would be wrong to sexually fondle an infant even if the infant was not physically harmed or traumatized. Our emotions confirm that such acts are wrong even if our usual justification for that conclusion (harm to the victim) is inapplicable.

If morals are emotionally based, then people who lack strong emotions should be blind to the moral domain. This prediction is borne out by psychopaths, who, it turns out, suffer from profound emotional deficits. Psychologist James Blair has shown that psychopaths treat moral rules as mere conventions. This suggests that emotions are necessary for making moral judgments. The judgment that something is morally wrong is an emotional response.

It doesn't follow that every emotional response is a moral judgment. Morality involves specific emotions. Research suggests that the main moral emotions are anger and disgust when an action is performed by another person, and guilt and shame when an action is performed by oneself. Arguably, one doesn't harbour a moral attitude towards something unless one is disposed to have both these self- and other-directed emotions. You may be disgusted by eating cow tongue, but unless you are a moral vegetarian, you wouldn't be ashamed of eating it.

In some cases, the moral emotions that get conditioned in childhood can be re-conditioned later in life. Someone who feels ashamed of a homosexual desire may subsequently feel ashamed about feeling ashamed. This person can be said to have an inculcated tendency to view homosexuality as immoral, but also a conviction that homosexuality is permissible, and the latter serves to curb the former over time.

In summary, moral judgments are based on emotions, and reasoning normally contributes only by helping us extrapolate from our basic values to novel cases. Reasoning can also lead us to discover that our basic values are culturally inculcated, and that might impel us to search for alternative values, but reason alone cannot tell us which values to adopt, nor can it instil new values.

Q. Which of the following statements best sum up the note on which the author ends the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Children begin to learn values when they are very young, before they can reason effectively. Young children behave in ways that we would never accept in adults: they scream, throw food, take off their clothes in public, hit, scratch, bite, and generally make a ruckus. Moral education begins from the start, as parents correct these antisocial behaviours, and they usually do so by conditioning children's emotions. Parents threaten physical punishment ("Do you want a spanking?"), they withdraw love ("I'm not going to play with you anymore!"), ostracize ("Go to your room!"), deprive ("No dessert for you!"), and induce vicarious distress ("Look at the pain you've caused!"). Each of these methods causes the misbehaved child to experience a negative emotion and associate it with the punished behaviour. Children also learn by emotional osmosis. They see their parents' reactions to news broadcasts and storybooks. They hear hours of judgmental gossip about inconsiderate neighbours, unethical co-workers, disloyal friends, and the black sheep in the family.

Emotional conditioning and osmosis are not merely convenient tools for acquiring values: they are essential. Parents sometimes try to reason with their children, but moral reasoning only works by drawing attention to values that the child has already internalized through emotional conditioning. No amount of reasoning can engender a moral value, because all values are, at bottom, emotional attitudes. Recent research in psychology supports this conjecture. It seems that we decide whether something is wrong by introspecting our feelings: if an action makes us feel bad, we conclude that it is wrong. Consistent with this, people's moral judgments can be shifted by simply altering their emotional states.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues have shown that people make moral judgments even when they cannot provide any justification for them. For example, 80% of the American college students in Haidt's study said it's wrong for two adult siblings to have consensual sex with each other even if they use contraception and no one is harmed. And, in a study I ran, 100% of people agreed it would be wrong to sexually fondle an infant even if the infant was not physically harmed or traumatized. Our emotions confirm that such acts are wrong even if our usual justification for that conclusion (harm to the victim) is inapplicable.

If morals are emotionally based, then people who lack strong emotions should be blind to the moral domain. This prediction is borne out by psychopaths, who, it turns out, suffer from profound emotional deficits. Psychologist James Blair has shown that psychopaths treat moral rules as mere conventions. This suggests that emotions are necessary for making moral judgments. The judgment that something is morally wrong is an emotional response.

It doesn't follow that every emotional response is a moral judgment. Morality involves specific emotions. Research suggests that the main moral emotions are anger and disgust when an action is performed by another person, and guilt and shame when an action is performed by oneself. Arguably, one doesn't harbour a moral attitude towards something unless one is disposed to have both these self- and other-directed emotions. You may be disgusted by eating cow tongue, but unless you are a moral vegetarian, you wouldn't be ashamed of eating it.

In some cases, the moral emotions that get conditioned in childhood can be re-conditioned later in life. Someone who feels ashamed of a homosexual desire may subsequently feel ashamed about feeling ashamed. This person can be said to have an inculcated tendency to view homosexuality as immoral, but also a conviction that homosexuality is permissible, and the latter serves to curb the former over time.

In summary, moral judgments are based on emotions, and reasoning normally contributes only by helping us extrapolate from our basic values to novel cases. Reasoning can also lead us to discover that our basic values are culturally inculcated, and that might impel us to search for alternative values, but reason alone cannot tell us which values to adopt, nor can it instil new values.

Q. Which of the following best sums up the central idea of the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Kumaon, the northernmost region of Uttarakhand (a state in India), shines under the Himalayan sun and snow and gushes with water shared with the nation of Nepal. This bond runs thousands of years old, and has only in modern times been obscured by a 225 km border. The traditions of trade and migration - where Kumaoni goods spanned out to Tibet and Central Asia through Nepal, or where Nepalese people dwelling in mountain villages came down to the warmer and more inhabited Kumaon - made the Himalayan range seem less of a geographical barrier and more a home to transnational cultures and incredible religious tolerance.

Though the geographical isolation that the Himalayas brought about could have very easily caused distinction between ethnic and cultural groups and raised barriers to cultural diffusion, the economic and social conditions led to greater tolerance of intermarriage. Parents blessed marriages of couples whose origins were often hundreds of kilometres apart. As a result, love marriages, though not so common, were also accepted in this region, where arranged marriages were usually the norm.

In short, intermarriage and cultural diffusion fuelled each other across the Indo-Nepalese border. The traditions of both regions, which are neither "purely" from those regions, emphasize this fact. Hindus in Kumaon are less preoccupied with the caste system (though there is still discrimination that exists as a result of this hierarchy.) Buddhists in Nepal retain certain elements of Hinduism that were left with them even as the last of the Kumaoni migrant traders passed by their villages.

However, following British rule in India, the Anglo-Nepalese war, and the creation of geopolitical entities, the 225 km landscape which was once known as an open gate between kingdoms of India and Nepal became an established border. Centuries of open trade and intermarriage became closed off, and those who once lived within an autonomous Kumaon with its own kingdom and culture became, for the first time, to be known as Indians.

Even today, marriages take place across the border, and thus hold together ancient ties between families and different cultural and ethnic groups. For example, Nepalese men leave their homes for Kumaon in search of jobs and even the love of their life. Immigration between Nepal and India has extremely lax regulations - about 18 forms of ID are acceptable for passing through the border. Even if one cannot produce such ID, get permission, or get a fake passport (another common options) many Nepalese can still take advantage of obscure but dangerous pedestrian paths and cross rivers to get to the land that was once bound with theirs.

Once in the Kumaon region, Nepalese migrants usually work menial jobs and, in glaring contrast to their ancestors, are given the short end of the stick in terms of the social hierarchy. Not only are they looked down upon by many modern-day Kumaonis who consider themselves more Indian than Himalayan (though it merits mention that many Kumaonis still venerate the ancient ties with Nepal) but they also face their business often face crushing competitions from larger businesses with backing from Indian financial institutions.

This is further emphasized when one looks at the implications of many Indians immigrating freely into Nepal. The Nepalese government has complained time and again about migrant Indians luring Nepalese women into prostitution with empty promises of Bollywood and glamour. In addition, Indian dacoits (robbers or bandits) often take advantage of the porous border and spill into southern and western Nepal. In short, the tie is there, but it is not what it used to be.

Q. Which of the following options best sums up the central idea of the passage?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Kumaon, the northernmost region of Uttarakhand (a state in India), shines under the Himalayan sun and snow and gushes with water shared with the nation of Nepal. This bond runs thousands of years old, and has only in modern times been obscured by a 225 km border. The traditions of trade and migration - where Kumaoni goods spanned out to Tibet and Central Asia through Nepal, or where Nepalese people dwelling in mountain villages came down to the warmer and more inhabited Kumaon - made the Himalayan range seem less of a geographical barrier and more a home to transnational cultures and incredible religious tolerance.

Though the geographical isolation that the Himalayas brought about could have very easily caused distinction between ethnic and cultural groups and raised barriers to cultural diffusion, the economic and social conditions led to greater tolerance of intermarriage. Parents blessed marriages of couples whose origins were often hundreds of kilometres apart. As a result, love marriages, though not so common, were also accepted in this region, where arranged marriages were usually the norm.

In short, intermarriage and cultural diffusion fuelled each other across the Indo-Nepalese border. The traditions of both regions, which are neither "purely" from those regions, emphasize this fact. Hindus in Kumaon are less preoccupied with the caste system (though there is still discrimination that exists as a result of this hierarchy.) Buddhists in Nepal retain certain elements of Hinduism that were left with them even as the last of the Kumaoni migrant traders passed by their villages.

However, following British rule in India, the Anglo-Nepalese war, and the creation of geopolitical entities, the 225 km landscape which was once known as an open gate between kingdoms of India and Nepal became an established border. Centuries of open trade and intermarriage became closed off, and those who once lived within an autonomous Kumaon with its own kingdom and culture became, for the first time, to be known as Indians.

Even today, marriages take place across the border, and thus hold together ancient ties between families and different cultural and ethnic groups. For example, Nepalese men leave their homes for Kumaon in search of jobs and even the love of their life. Immigration between Nepal and India has extremely lax regulations - about 18 forms of ID are acceptable for passing through the border. Even if one cannot produce such ID, get permission, or get a fake passport (another common options) many Nepalese can still take advantage of obscure but dangerous pedestrian paths and cross rivers to get to the land that was once bound with theirs.

Once in the Kumaon region, Nepalese migrants usually work menial jobs and, in glaring contrast to their ancestors, are given the short end of the stick in terms of the social hierarchy. Not only are they looked down upon by many modern-day Kumaonis who consider themselves more Indian than Himalayan (though it merits mention that many Kumaonis still venerate the ancient ties with Nepal) but they also face their business often face crushing competitions from larger businesses with backing from Indian financial institutions.

This is further emphasized when one looks at the implications of many Indians immigrating freely into Nepal. The Nepalese government has complained time and again about migrant Indians luring Nepalese women into prostitution with empty promises of Bollywood and glamour. In addition, Indian dacoits (robbers or bandits) often take advantage of the porous border and spill into southern and western Nepal. In short, the tie is there, but it is not what it used to be.

Q. It can be understood that in the fourth paragraph, the key purpose of the author is to:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Kumaon, the northernmost region of Uttarakhand (a state in India), shines under the Himalayan sun and snow and gushes with water shared with the nation of Nepal. This bond runs thousands of years old, and has only in modern times been obscured by a 225 km border. The traditions of trade and migration - where Kumaoni goods spanned out to Tibet and Central Asia through Nepal, or where Nepalese people dwelling in mountain villages came down to the warmer and more inhabited Kumaon - made the Himalayan range seem less of a geographical barrier and more a home to transnational cultures and incredible religious tolerance.

Though the geographical isolation that the Himalayas brought about could have very easily caused distinction between ethnic and cultural groups and raised barriers to cultural diffusion, the economic and social conditions led to greater tolerance of intermarriage. Parents blessed marriages of couples whose origins were often hundreds of kilometres apart. As a result, love marriages, though not so common, were also accepted in this region, where arranged marriages were usually the norm.

In short, intermarriage and cultural diffusion fuelled each other across the Indo-Nepalese border. The traditions of both regions, which are neither "purely" from those regions, emphasize this fact. Hindus in Kumaon are less preoccupied with the caste system (though there is still discrimination that exists as a result of this hierarchy.) Buddhists in Nepal retain certain elements of Hinduism that were left with them even as the last of the Kumaoni migrant traders passed by their villages.

However, following British rule in India, the Anglo-Nepalese war, and the creation of geopolitical entities, the 225 km landscape which was once known as an open gate between kingdoms of India and Nepal became an established border. Centuries of open trade and intermarriage became closed off, and those who once lived within an autonomous Kumaon with its own kingdom and culture became, for the first time, to be known as Indians.

Even today, marriages take place across the border, and thus hold together ancient ties between families and different cultural and ethnic groups. For example, Nepalese men leave their homes for Kumaon in search of jobs and even the love of their life. Immigration between Nepal and India has extremely lax regulations - about 18 forms of ID are acceptable for passing through the border. Even if one cannot produce such ID, get permission, or get a fake passport (another common options) many Nepalese can still take advantage of obscure but dangerous pedestrian paths and cross rivers to get to the land that was once bound with theirs.

Once in the Kumaon region, Nepalese migrants usually work menial jobs and, in glaring contrast to their ancestors, are given the short end of the stick in terms of the social hierarchy. Not only are they looked down upon by many modern-day Kumaonis who consider themselves more Indian than Himalayan (though it merits mention that many Kumaonis still venerate the ancient ties with Nepal) but they also face their business often face crushing competitions from larger businesses with backing from Indian financial institutions.

This is further emphasized when one looks at the implications of many Indians immigrating freely into Nepal. The Nepalese government has complained time and again about migrant Indians luring Nepalese women into prostitution with empty promises of Bollywood and glamour. In addition, Indian dacoits (robbers or bandits) often take advantage of the porous border and spill into southern and western Nepal. In short, the tie is there, but it is not what it used to be.

Q. It can be inferred that the passage is most likely to be an excerpt from which of the following sources?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Kumaon, the northernmost region of Uttarakhand (a state in India), shines under the Himalayan sun and snow and gushes with water shared with the nation of Nepal. This bond runs thousands of years old, and has only in modern times been obscured by a 225 km border. The traditions of trade and migration - where Kumaoni goods spanned out to Tibet and Central Asia through Nepal, or where Nepalese people dwelling in mountain villages came down to the warmer and more inhabited Kumaon - made the Himalayan range seem less of a geographical barrier and more a home to transnational cultures and incredible religious tolerance.

Though the geographical isolation that the Himalayas brought about could have very easily caused distinction between ethnic and cultural groups and raised barriers to cultural diffusion, the economic and social conditions led to greater tolerance of intermarriage. Parents blessed marriages of couples whose origins were often hundreds of kilometres apart. As a result, love marriages, though not so common, were also accepted in this region, where arranged marriages were usually the norm.

In short, intermarriage and cultural diffusion fuelled each other across the Indo-Nepalese border. The traditions of both regions, which are neither "purely" from those regions, emphasize this fact. Hindus in Kumaon are less preoccupied with the caste system (though there is still discrimination that exists as a result of this hierarchy.) Buddhists in Nepal retain certain elements of Hinduism that were left with them even as the last of the Kumaoni migrant traders passed by their villages.

However, following British rule in India, the Anglo-Nepalese war, and the creation of geopolitical entities, the 225 km landscape which was once known as an open gate between kingdoms of India and Nepal became an established border. Centuries of open trade and intermarriage became closed off, and those who once lived within an autonomous Kumaon with its own kingdom and culture became, for the first time, to be known as Indians.

Even today, marriages take place across the border, and thus hold together ancient ties between families and different cultural and ethnic groups. For example, Nepalese men leave their homes for Kumaon in search of jobs and even the love of their life. Immigration between Nepal and India has extremely lax regulations - about 18 forms of ID are acceptable for passing through the border. Even if one cannot produce such ID, get permission, or get a fake passport (another common options) many Nepalese can still take advantage of obscure but dangerous pedestrian paths and cross rivers to get to the land that was once bound with theirs.

Once in the Kumaon region, Nepalese migrants usually work menial jobs and, in glaring contrast to their ancestors, are given the short end of the stick in terms of the social hierarchy. Not only are they looked down upon by many modern-day Kumaonis who consider themselves more Indian than Himalayan (though it merits mention that many Kumaonis still venerate the ancient ties with Nepal) but they also face their business often face crushing competitions from larger businesses with backing from Indian financial institutions.

This is further emphasized when one looks at the implications of many Indians immigrating freely into Nepal. The Nepalese government has complained time and again about migrant Indians luring Nepalese women into prostitution with empty promises of Bollywood and glamour. In addition, Indian dacoits (robbers or bandits) often take advantage of the porous border and spill into southern and western Nepal. In short, the tie is there, but it is not what it used to be.

Q. It can be understood from the context of the passage that which of the following would seamlessly follow the last paragraph?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The higher education system is a unique type of organisation with its own way of motivating productivity in its scholarly workforce. It doesn’t need to compel professors to produce scholarship because they choose to do it on their own. This is in contrast to the standard structure for motivating employees in bureaucratic organisations, which relies on manipulating two incentives: fear and greed. Fear works by holding the threat of firing over the heads of workers in order to ensure that they stay in line: Do it my way, or you’re out of here. Greed works by holding the prospect of pay increases and promotions in front of workers in order to encourage them to exhibit the work behaviours that will bring these rewards: Do it my way and you’ll get what’s yours.

Yes, in the United States contingent faculty can be fired at any time, and permanent faculty can be fired at the point of tenure. But, once tenured, there’s little other than criminal conduct or gross negligence that can threaten your job. And yes, most colleges do have merit pay systems that reward more productive faculty with higher salaries. But the differences are small - between the standard 3 per cent raise and a 4 per cent merit increase. Even though gaining consistent above-average raises can compound annually into substantial differences over time, the immediate rewards are pretty underwhelming. Not the kind of incentive that would motivate a major expenditure of effort in a given year - such as the kind that operates on Wall Street, where earning a million-dollar bonus is a real possibility. Academic administrators - chairs, deans, presidents - just don’t have this kind of power over faculty. It’s why we refer to academic leadership as an exercise in herding cats. Deans can ask you to do something, but they really can’t make you do it.

This situation is the norm for systems of higher education in most liberal democracies around the world. In more authoritarian settings, the incentives for faculty are skewed by particular political priorities, and in part, for these reasons, the institutions in those settings tend to be consigned to the lower tiers of international rankings. Scholarly autonomy is a defining characteristic of universities higher on the list.

If the usual extrinsic incentives of fear and greed don’t apply to academics, then what does motivate them to be productive scholars? One factor, of course, is that this population is highly self-selected. People don’t become professors in order to gain power and money. They enter the role primarily because of a deep passion for a particular field of study. They find that scholarship is a mode of work that is intrinsically satisfying. It’s more a vocation than a job. And these elements tend to be pervasive in most of the world’s universities. But I want to focus on an additional powerful motivation that drives academics, one that we don’t talk about very much. Once launched into an academic career, faculty members find their scholarly efforts spurred on by more than a love of the work. We in academia are motivated by a lust for glory.

We want to be recognised for our academic accomplishments by earning our own little pieces of fame. So we work assiduously to accumulate a set of merit badges over the course of our careers, which we then proudly display on our CVs. This situation is particularly pervasive in the US system of higher education, which is organised more by the market than by the state. Market systems are especially prone to the accumulation of distinctions that define your position in the hierarchy. But European and other scholars are also engaged in a race to pick up honours and add lines to their CVs. It’s the universal obsession of the scholarly profession.

Q. According to the passage, more than any other factor, academics are motivated by:

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The higher education system is a unique type of organisation with its own way of motivating productivity in its scholarly workforce. It doesn’t need to compel professors to produce scholarship because they choose to do it on their own. This is in contrast to the standard structure for motivating employees in bureaucratic organisations, which relies on manipulating two incentives: fear and greed. Fear works by holding the threat of firing over the heads of workers in order to ensure that they stay in line: Do it my way, or you’re out of here. Greed works by holding the prospect of pay increases and promotions in front of workers in order to encourage them to exhibit the work behaviours that will bring these rewards: Do it my way and you’ll get what’s yours.

Yes, in the United States contingent faculty can be fired at any time, and permanent faculty can be fired at the point of tenure. But, once tenured, there’s little other than criminal conduct or gross negligence that can threaten your job. And yes, most colleges do have merit pay systems that reward more productive faculty with higher salaries. But the differences are small - between the standard 3 per cent raise and a 4 per cent merit increase. Even though gaining consistent above-average raises can compound annually into substantial differences over time, the immediate rewards are pretty underwhelming. Not the kind of incentive that would motivate a major expenditure of effort in a given year - such as the kind that operates on Wall Street, where earning a million-dollar bonus is a real possibility. Academic administrators - chairs, deans, presidents - just don’t have this kind of power over faculty. It’s why we refer to academic leadership as an exercise in herding cats. Deans can ask you to do something, but they really can’t make you do it.

This situation is the norm for systems of higher education in most liberal democracies around the world. In more authoritarian settings, the incentives for faculty are skewed by particular political priorities, and in part, for these reasons, the institutions in those settings tend to be consigned to the lower tiers of international rankings. Scholarly autonomy is a defining characteristic of universities higher on the list.

If the usual extrinsic incentives of fear and greed don’t apply to academics, then what does motivate them to be productive scholars? One factor, of course, is that this population is highly self-selected. People don’t become professors in order to gain power and money. They enter the role primarily because of a deep passion for a particular field of study. They find that scholarship is a mode of work that is intrinsically satisfying. It’s more a vocation than a job. And these elements tend to be pervasive in most of the world’s universities. But I want to focus on an additional powerful motivation that drives academics, one that we don’t talk about very much. Once launched into an academic career, faculty members find their scholarly efforts spurred on by more than a love of the work. We in academia are motivated by a lust for glory.

We want to be recognised for our academic accomplishments by earning our own little pieces of fame. So we work assiduously to accumulate a set of merit badges over the course of our careers, which we then proudly display on our CVs. This situation is particularly pervasive in the US system of higher education, which is organised more by the market than by the state. Market systems are especially prone to the accumulation of distinctions that define your position in the hierarchy. But European and other scholars are also engaged in a race to pick up honours and add lines to their CVs. It’s the universal obsession of the scholarly profession.

Q. Which of the following, if true, would do most to undermine the main point of the second paragraph?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The higher education system is a unique type of organisation with its own way of motivating productivity in its scholarly workforce. It doesn’t need to compel professors to produce scholarship because they choose to do it on their own. This is in contrast to the standard structure for motivating employees in bureaucratic organisations, which relies on manipulating two incentives: fear and greed. Fear works by holding the threat of firing over the heads of workers in order to ensure that they stay in line: Do it my way, or you’re out of here. Greed works by holding the prospect of pay increases and promotions in front of workers in order to encourage them to exhibit the work behaviours that will bring these rewards: Do it my way and you’ll get what’s yours.

Yes, in the United States contingent faculty can be fired at any time, and permanent faculty can be fired at the point of tenure. But, once tenured, there’s little other than criminal conduct or gross negligence that can threaten your job. And yes, most colleges do have merit pay systems that reward more productive faculty with higher salaries. But the differences are small - between the standard 3 per cent raise and a 4 per cent merit increase. Even though gaining consistent above-average raises can compound annually into substantial differences over time, the immediate rewards are pretty underwhelming. Not the kind of incentive that would motivate a major expenditure of effort in a given year - such as the kind that operates on Wall Street, where earning a million-dollar bonus is a real possibility. Academic administrators - chairs, deans, presidents - just don’t have this kind of power over faculty. It’s why we refer to academic leadership as an exercise in herding cats. Deans can ask you to do something, but they really can’t make you do it.

This situation is the norm for systems of higher education in most liberal democracies around the world. In more authoritarian settings, the incentives for faculty are skewed by particular political priorities, and in part, for these reasons, the institutions in those settings tend to be consigned to the lower tiers of international rankings. Scholarly autonomy is a defining characteristic of universities higher on the list.

If the usual extrinsic incentives of fear and greed don’t apply to academics, then what does motivate them to be productive scholars? One factor, of course, is that this population is highly self-selected. People don’t become professors in order to gain power and money. They enter the role primarily because of a deep passion for a particular field of study. They find that scholarship is a mode of work that is intrinsically satisfying. It’s more a vocation than a job. And these elements tend to be pervasive in most of the world’s universities. But I want to focus on an additional powerful motivation that drives academics, one that we don’t talk about very much. Once launched into an academic career, faculty members find their scholarly efforts spurred on by more than a love of the work. We in academia are motivated by a lust for glory.

We want to be recognised for our academic accomplishments by earning our own little pieces of fame. So we work assiduously to accumulate a set of merit badges over the course of our careers, which we then proudly display on our CVs. This situation is particularly pervasive in the US system of higher education, which is organised more by the market than by the state. Market systems are especially prone to the accumulation of distinctions that define your position in the hierarchy. But European and other scholars are also engaged in a race to pick up honours and add lines to their CVs. It’s the universal obsession of the scholarly profession.

Q. Which of the following statements would the author agree with?

Read the passage and answer the following questions.

Publishing the Quran and making it available in translation was a dangerous enterprise in the 16th century, apt to confuse or seduce the faithful Christian. This, at least, was the opinion of the Protestant city councillors of Basel in 1542, when they briefly jailed a local printer for planning to publish a Latin translation of the Muslim holy book. The Protestant reformer Martin Luther intervened to salvage the project: there was no better way to combat the Turk, he wrote, than to expose the ‘lies of Muhammad’ for all to see.

The resulting publication in 1543 made the Quran available to European intellectuals, most of whom studied it in order to better understand and combat Islam. There were others, however, who used their reading of the Quran to question Christian doctrine. The Catalonian polymath and theologian Michael Servetus found numerous Quranic arguments to employ in his anti-Trinitarian tract, Christianismi Restitutio (1553), in which he called Muhammad a true reformer who preached a return to the pure monotheism that Christian theologians had corrupted by inventing the perverse and irrational doctrine of the Trinity. After publishing these heretical ideas, Servetus was condemned by the Catholic Inquisition in Vienne, and finally burned with his own books in Calvin’s Geneva.

During the European Enlightenment, a number of authors presented Muhammad in a similar vein, as an anticlerical hero; some saw Islam as a pure form of monotheism close to philosophic Deism and the Quran as a rational paean to the Creator. In 1734, George Sale published a new English translation. In his introduction, he traced the early history of Islam and idealised the Prophet as an iconoclastic, anticlerical reformer who had banished the ‘superstitious’ beliefs and practices of early Christians - the cult of the saints, holy relics - and quashed the power of a corrupt and avaricious clergy.

Sale’s translation of the Quran was widely read and appreciated in England: for many of his readers, Muhammad had become a symbol of anticlerical republicanism. It was influential outside England too. The US founding father Thomas Jefferson bought a copy from a bookseller in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1765, which helped him conceive of a philosophical deism that surpassed confessional boundaries. (Jefferson’s copy, now in the Library of Congress, has been used for the swearing in of Muslim representatives to Congress, starting with Keith Ellison in 2007.) And in Germany, the Romantic Johann Wolfgang von Goethe read a translation of Sale’s version, which helped to colour his evolving notion of Muhammad as an inspired poet and archetypal prophet.

Q. What is the purpose of the penultimate paragraph?

Read the passage and answer the following questions.

Publishing the Quran and making it available in translation was a dangerous enterprise in the 16th century, apt to confuse or seduce the faithful Christian. This, at least, was the opinion of the Protestant city councillors of Basel in 1542, when they briefly jailed a local printer for planning to publish a Latin translation of the Muslim holy book. The Protestant reformer Martin Luther intervened to salvage the project: there was no better way to combat the Turk, he wrote, than to expose the ‘lies of Muhammad’ for all to see.

The resulting publication in 1543 made the Quran available to European intellectuals, most of whom studied it in order to better understand and combat Islam. There were others, however, who used their reading of the Quran to question Christian doctrine. The Catalonian polymath and theologian Michael Servetus found numerous Quranic arguments to employ in his anti-Trinitarian tract, Christianismi Restitutio (1553), in which he called Muhammad a true reformer who preached a return to the pure monotheism that Christian theologians had corrupted by inventing the perverse and irrational doctrine of the Trinity. After publishing these heretical ideas, Servetus was condemned by the Catholic Inquisition in Vienne, and finally burned with his own books in Calvin’s Geneva.

During the European Enlightenment, a number of authors presented Muhammad in a similar vein, as an anticlerical hero; some saw Islam as a pure form of monotheism close to philosophic Deism and the Quran as a rational paean to the Creator. In 1734, George Sale published a new English translation. In his introduction, he traced the early history of Islam and idealised the Prophet as an iconoclastic, anticlerical reformer who had banished the ‘superstitious’ beliefs and practices of early Christians - the cult of the saints, holy relics - and quashed the power of a corrupt and avaricious clergy.

Sale’s translation of the Quran was widely read and appreciated in England: for many of his readers, Muhammad had become a symbol of anticlerical republicanism. It was influential outside England too. The US founding father Thomas Jefferson bought a copy from a bookseller in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1765, which helped him conceive of a philosophical deism that surpassed confessional boundaries. (Jefferson’s copy, now in the Library of Congress, has been used for the swearing in of Muslim representatives to Congress, starting with Keith Ellison in 2007.) And in Germany, the Romantic Johann Wolfgang von Goethe read a translation of Sale’s version, which helped to colour his evolving notion of Muhammad as an inspired poet and archetypal prophet.

Q. Why does the author cite the examples of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Thomas Jefferson?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the question.

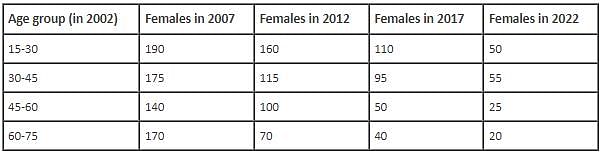

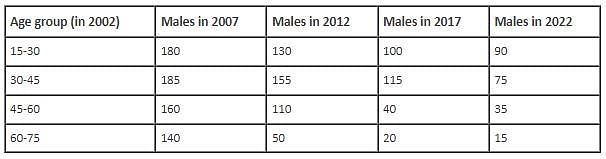

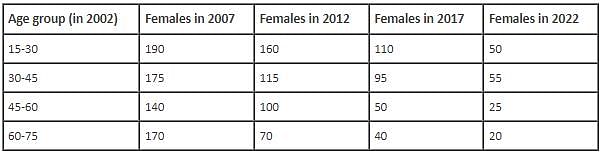

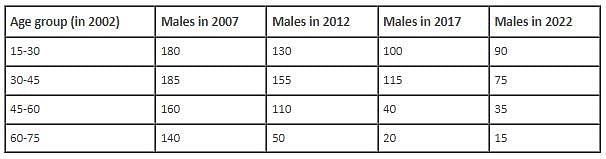

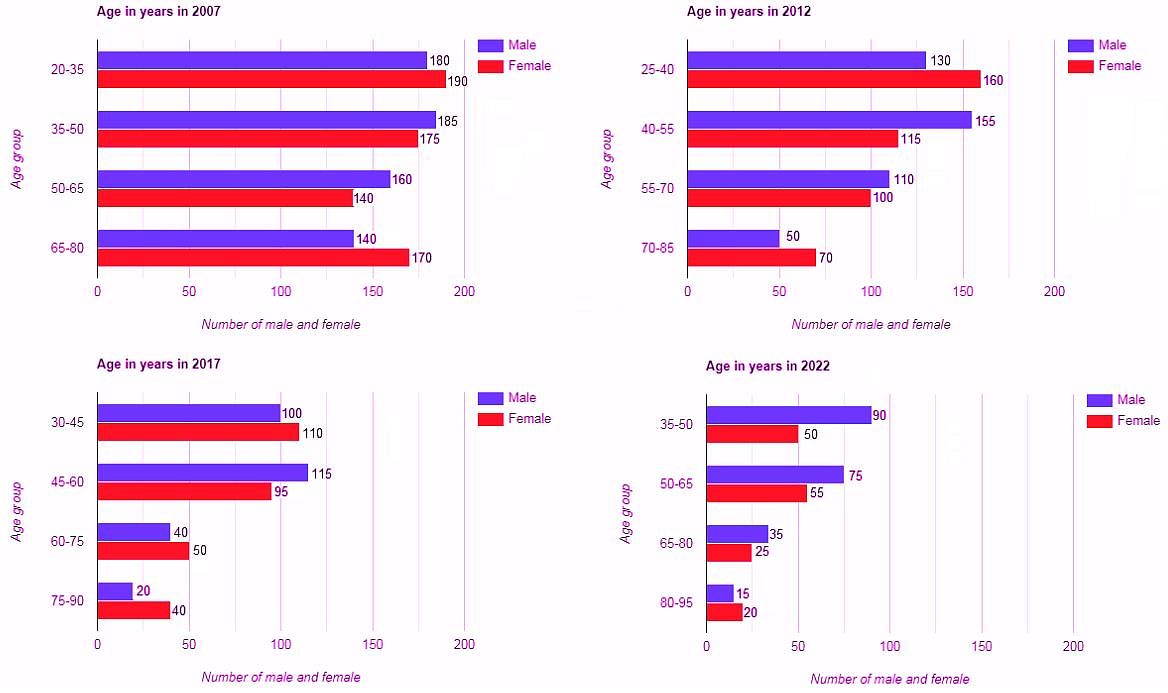

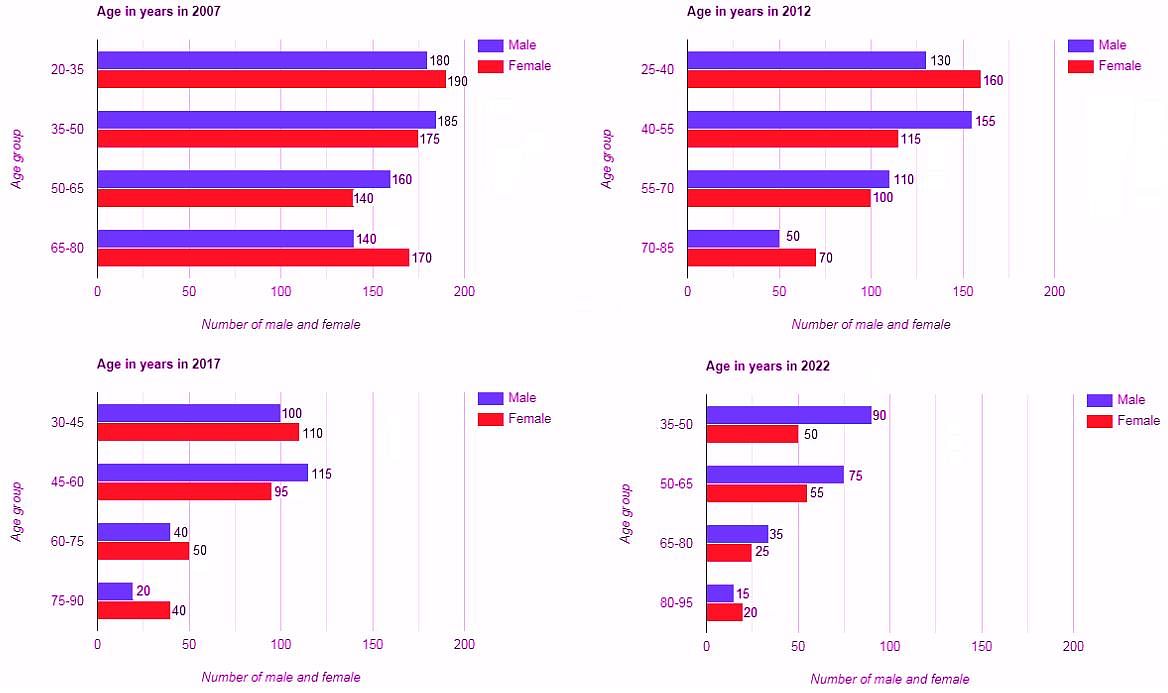

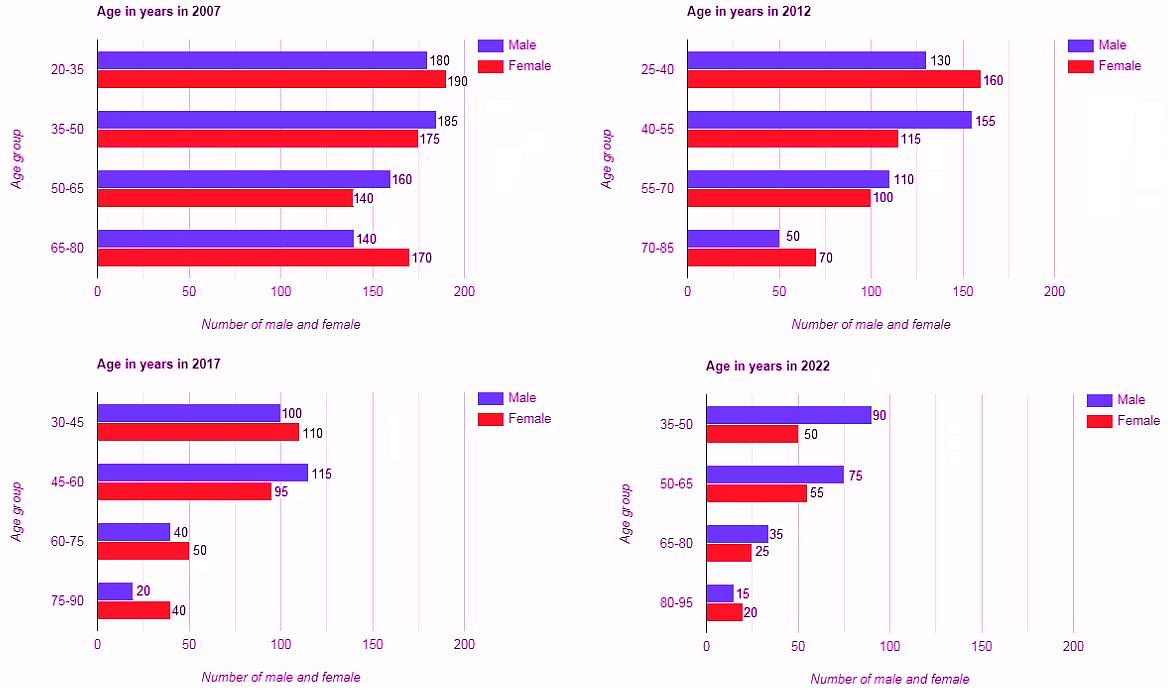

In a research study conducted in 2002, a team of scientists embarked on a mission to investigate the impact of air pollution on respiratory health. They carefully selected a diverse group of 1600 participants, comprising 800 males and 800 females, to participate in the study. The study aimed to monitor their respiratory health for a duration of 5 years, tracking death caused by any respiratory-related conditions or ailments that developed during this period. To ensure representation across various age groups, the 800 male participants were categorised into four distinct age brackets: 200 individuals between the ages of 15 and less than 30, 200 between 30 and less than 45, 200 between 45 and less than 60, and another 200 between 60 and less than 75. Similarly, the 800 female participants were equally divided into the same age groups. Over the course of the study, data was collected at specific intervals to analyse the alive participants' respiratory health. Specifically, assessments were conducted in the years 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2022. The findings were visually depicted in graphs.

Q. Find the number of females in the age group 20-35 in 2007 who died between 2012 and 2017.

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the question.

In a research study conducted in 2002, a team of scientists embarked on a mission to investigate the impact of air pollution on respiratory health. They carefully selected a diverse group of 1600 participants, comprising 800 males and 800 females, to participate in the study. The study aimed to monitor their respiratory health for a duration of 5 years, tracking death caused by any respiratory-related conditions or ailments that developed during this period. To ensure representation across various age groups, the 800 male participants were categorised into four distinct age brackets: 200 individuals between the ages of 15 and less than 30, 200 between 30 and less than 45, 200 between 45 and less than 60, and another 200 between 60 and less than 75. Similarly, the 800 female participants were equally divided into the same age groups. Over the course of the study, data was collected at specific intervals to analyse the alive participants' respiratory health. Specifically, assessments were conducted in the years 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2022. The findings were visually depicted in graphs.

Q. What is the ratio of the number of dead males to that of dead females in 2012?

Directions: Study the following information carefully and answer the question.

In a research study conducted in 2002, a team of scientists embarked on a mission to investigate the impact of air pollution on respiratory health. They carefully selected a diverse group of 1600 participants, comprising 800 males and 800 females, to participate in the study. The study aimed to monitor their respiratory health for a duration of 5 years, tracking death caused by any respiratory-related conditions or ailments that developed during this period. To ensure representation across various age groups, the 800 male participants were categorised into four distinct age brackets: 200 individuals between the ages of 15 and less than 30, 200 between 30 and less than 45, 200 between 45 and less than 60, and another 200 between 60 and less than 75. Similarly, the 800 female participants were equally divided into the same age groups. Over the course of the study, data was collected at specific intervals to analyse the alive participants' respiratory health. Specifically, assessments were conducted in the years 2007, 2012, 2017, and 2022. The findings were visually depicted in graphs.

Q. The number of people in the age group of 60-75 in 2002 survived until 2022 is

Ram borrowed Rs 72000 at 20% p.a compound interest, the interest being compounded annually. He repaid x at the end of the first year and 57600 at the end of the second year and he cleared the loan. The amount he paid at the end of the first year was.

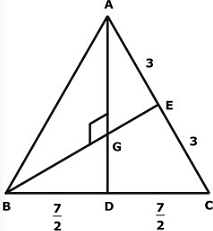

In ΔABC, the median from A is perpendicular to the median from B. If AC = 6, BC = 7, what is the length of AB?

Let us assume we have an eight face die numbered from 1 to 8. What is the probability that exactly two of the eight numbers appear on the top face in the five throws of an unbiased die?

Water flows at a speed of 30 km/h through a cylindrical pipe of inner radius 1.5 m into a tank of 100 m 150 m. In what time (in minutes rounded off to the nearest integer) will the water rise by 4 m?

A pair of straight lines is expressed as 2x2 - 3 = 0. The straight lines are ____________ to each other. Fill in the blank.

Two types of lemonade (lemon syrup and water) X and Y were mixed in the proportion 1 : 4 by volume. Later on, volume of the mixture was tripled by adding lemonade X such that resulting mixture had 60% water. If lemonade X has 50% water, then the percentage of water in lemonade Y is __________ (Key in the percent value up to two decimal places).

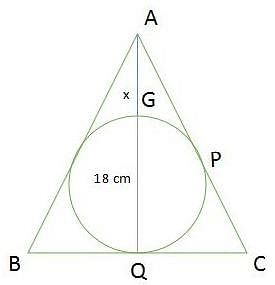

A circle of radius 9 cm is inscribed inside a triangle ABC. Side AC touches the circle at P and side BC touches the circle at Q. If the length of AP is 12 cm, what is the length(in cm) of AQ ?

Aruj can fill a large tank from a river with a bucket in 40 minutes, Anik is 25% more efficient than Aruj and Rhitam is 20% more efficient than Anik. Aruj and Anik are allotted for filling up the tank. Rhitam, being a naughty kid, starts emptying the tank. Assuming filling the tank requires equal time and effort as that for emptying, what is the time required to fill the tank?

Banta Singh was driving to Lonawala when his truck suddenly stops. He realised that the truck has run out of diesel, He remembered that he has a can holding 'P' liters of diesel and promptly emptied it into the right circular cylindrical diesel tank. He then inserted a straight stick vertically into the tank such that the free end of stick touches the bottom of the tank. He found that E% of stick left dry. After traveling a few kilometers (for which fuel consumption is negligible), he reached a refueling station. Now how many litres of diesel will be needed to fill the diesel tank of Banta's truck?