IIFT Mock Test - 2 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 2 (New Pattern)

Directions: In the following question, the options A, B, C and D have a word written in four different ways, of which only one is correct Identify the correctly spelt word.

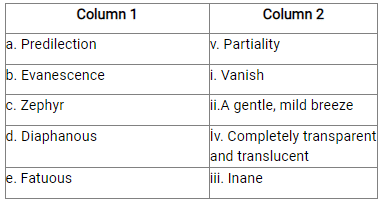

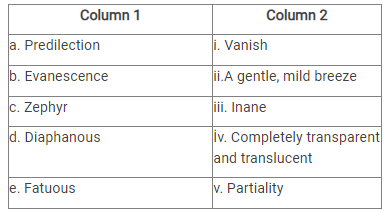

Directions: Match the words in column I with their appropriate meanings in column 2.

Form correct sentence by choosing right order of the given parts.

Education is

A. of a sense of responsibility

B. the first step

C. in a citizen

D. for the development

Directions: Pick the best option which completes the sentence in the most meaningful manner.

Q. _____________ made after English settlers came to Jamestown was a map of Virginia by John Smith, the famous adventurer.

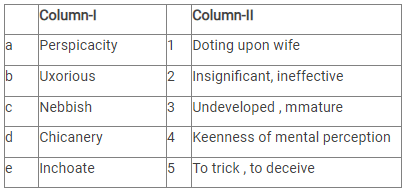

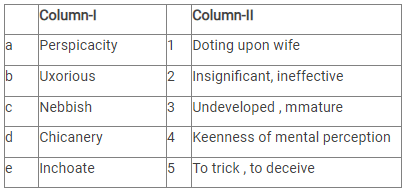

Directions: Match the words in column I with their appropriate meanings in column 2.

Directions: In the question below, there are two sentences containing underlined homonyms, which may either be mis-spelt or inappropriately toed in the context of the sentence. Select the appropriate answer from the options given below:

I. This behaviour does not compliment his position.

II. He thanked his boss for the complement.

Directions: Choose the word from the options which is Opposite in meaning to the given word.

Risible:

Which of the following words is spelled correctly?

Directions: The sentence below has four underlined words or phrases, marked A, B, C and D. Identify the underlined part that must be changed to make the sentence correct.

Being/ (A) a short holiday / (B) we had to return / (C) without visiting many of the places / (D).

Directions: For the following sentence, choose the most appropriate "one word" for the given expressions.

Q. One who is unrelenting and cannot be moved by entreaties:

Directions: Pick the best option which completes the sentence in the most meaningful manner.

Q. The concert this weekend promises to attract _____________ than attended the last one.

Directions: Given below are the first and last parts of a sentence, and the remaining sentence is broken into four parts p, q, r and s. From A, B, C and D, choose the arrangement of these parts that forms a complete, meaningful sentence.

Q. A number of measures ____________ of the Municipal Corporations.

p. the financial conditions.

q. for mobilisation of resources.

r. in order to improve.

s. are being taken by the State Governments.

Directions: A partially completed paragraph is placed below, followed by fillers a, b, c. From options A, B, C and D, identify the right combination and order of fillers a, b or c that will best complete the paragraph.

Forests are gifts of nature. (_______________). Yet, with the spread of civilisation, man has not only spurned the forests, but has been ruthlessly destroying them.

a. It is on historical record that the vast Sahara desert of today once used to be full of thick forests.

b. A large part of humanity still lives deep inside forests, particularly in the tropical regions of the earth.

c. Human evolution itself has taken place in the forests.

Directions: Choose the most logical order of sentences from among the given choices to construct a coherent paragraph.

(1) food supply

(2) storage, distribution and handling

(3) pastoral industry and fishing,

(4) besides increasing

(5) by preventing wastage in

(6) the productivity from agriculture

(7) can be increased

Directions: In the question below, there are two sentences containing underlined homonyms, which may either be mis-spelt or inappropriately toed in the context of the sentence. Select the appropriate answer from the options given below:

I. A vote of censur was passed against the Chairman.

II. Before release, every film is passed by the Censor Board.

Directions: Choose the word from the options which is Opposite in meaning to the given word.

Tenebrous:

Directions: Read the question and answer accordingly.

Q. Which of the following cannot be termed as an 'oxymoron'?

Directions: A partially completed paragraph is placed below, followed by fillers a, b, c. From options A, B, C and D, identify the right combination and order of fillers a, b or c that will best complete the paragraph.

In cultivating team spirit, one should not forget the importance of discipline. (________________) It is the duty of all the members of the team to observe discipline in its proper perspective.

a. A proper team spirit can seldom be based on discipline.

b. It is a well known fact that team spirit and discipline can never go hand in hand.

c. Discipline in its right perspective would mean sacrificing self to some extent.

Directions: For the following sentence, choose the most appropriate "one word" for the given expressions.

Q. The art of cutting trees and bushes into ornamental shapes:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language-so the argument runs-must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits, one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.

Q. Many people believe that nothing can be done about the English language because –

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language-so the argument runs-must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits, one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.

Q. The author believes that –

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language-so the argument runs-must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits, one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.

Q. The author believes that –

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language-so the argument runs-must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits, one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.

Q. The author believes that the first stage towards the political regeneration of the language would be –

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I have tried to introduce into the discussion a number of attributes of consumer behaviour and motivations, which I believe are important inputs into devising a strategy for commercially viable financial inclusion. These related broadly to the (i) the sources of livelihood of the potential consumer segment for financial inclusion (ii) how they spend their money, particularly on non-regular items (iii) their choices and motivations with respect to saving and (iv) their motivations for borrowing and their ability to access institutional sources of finance for their basic requirements. In discussing each of these sets of issues, I spent some time drawing implications for business strategies by financial service providers. In this section, I wilt briefly highlight, at the risk of some repetition, what I consider to be the key messages of the lecture.

The first message emerges from the preliminary discussion on the current scenario on financial inclusion, both at the aggregate level and across income categories. The data suggest that even savings accounts, the most basic financial service, have low penetration amongst the lowest income households. I want to emphasize that we are not talking about Below Poverty Line households only; Rs. 50,000 per year in 2007, while perhaps not quite middle class, was certainly quite far above the official poverty line. The same concerns about lack of penetration amongst the lowest income group for loans also arise. To reiterate the question that arises from these data patterns: is this because people can't access banks or other service providers or because they don't see value in doing so? This question needs to be addressed if an effective inclusion strategy is to be developed.

The second message is that the process of financial inclusion is going to be incomplete and inadequate if it is measured only in terms of new accounts being opened and operated. From the employment and earning patterns, there emerged a sense that better access to various kinds of financial services would help to increase the livelihood potential of a number of occupational categories, which in turn would help reduce the income differentials between these and more regular, salaried jobs. The fact that a huge proportion of the Indian workforce is either self-employed and in the casual labour segment suggests the need for products that will make access to credit easier to the former, while offering opportunities for risk mitigation and consumption smoothing to the latter.

The third message emerges from the analysis of expenditure patterns is the significance of infrequent, but quantitatively significant expenditures like ceremonies and medical costs. Essentially, dealing with these kinds of expenditures requires either low-cost insurance options, supported by a correspondingly low-cost health care system or a low level systematic investment plan, which allows even poor households to create enough of a buffer to deal with these demands as and when they arise. As has already been pointed out, it is not as though such products are not being offered by domestic financial service providers. It is really a matter of extending them to make them accessible to a very large number of lower income households, with a low and possibly uncertain ability to maintain regular contributions.

The fourth message comes strongly from the motivations to both save and borrow, which, as one might reasonably expect, significantly overlap with each other. It is striking that the need to deal with emergencies, both financial and medical, plays such an important role in both sets of motivations. The latter is, as has been said, amenable to a low-coat mass insurance scheme, with the attendant service provision. However, the former, which is a theme that recurs through the entire discussion on consumer characteristics, certainly suggests that the need for some kind of income and consumption smoothing product is a significant one in an effective financial inclusion agenda. This, of course, raises broader questions about the role of social safety nets, which offer at least some minimum income security and consumption smoothing. How extensive these mechanisms should be, how much security they should offer and for how long and how they should be financed are fundamental policy questions that go beyond the realm of the financial sector. However, to the extent that risk mitigation is a significant financial need, it must receive due attention of any meaningful financial inclusion strategy, in a way which provides practical answers to all these three questions.

The fifth and final message is actually the point I began the lecture with. It is the critical importance of the principle of commercial viability. Every aspect of a financial inclusion strategy - whether it is the design of products and services or the delivery mechanism -needs to be viewed in terms of the business opportunity that it offers and not as a deliverable that has been imposed on the service provider. However, it is also important to emphasize that commercial viability need not necessarily be viewed in terms of immediate cost and profitability calculations. Like in many other products, financial services also offer the prospect of a life-cycle model of marketing. Establishing a relationship with first-time consumers of financial products and services offers the opportunity to leverage this relationship into a wider set of financial transactions as at least some of these consumers move steadily up the income ladder. In fact, in a high growth scenario, a high proportion of such households are likely to move quite quickly from very basic financial services to more and more sophisticated ones. In other words, the commercial viability and profitability of a financial inclusion strategy need not be viewed only from the perspective of immediacy. There is a viable investment dimension to it as well.

Q. Identify the wrong statement from the following:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I have tried to introduce into the discussion a number of attributes of consumer behaviour and motivations, which I believe are important inputs into devising a strategy for commercially viable financial inclusion. These related broadly to the (i) the sources of livelihood of the potential consumer segment for financial inclusion (ii) how they spend their money, particularly on non-regular items (iii) their choices and motivations with respect to saving and (iv) their motivations for borrowing and their ability to access institutional sources of finance for their basic requirements. In discussing each of these sets of issues, I spent some time drawing implications for business strategies by financial service providers. In this section, I wilt briefly highlight, at the risk of some repetition, what I consider to be the key messages of the lecture.

The first message emerges from the preliminary discussion on the current scenario on financial inclusion, both at the aggregate level and across income categories. The data suggest that even savings accounts, the most basic financial service, have low penetration amongst the lowest income households. I want to emphasize that we are not talking about Below Poverty Line households only; Rs. 50,000 per year in 2007, while perhaps not quite middle class, was certainly quite far above the official poverty line. The same concerns about lack of penetration amongst the lowest income group for loans also arise. To reiterate the question that arises from these data patterns: is this because people can't access banks or other service providers or because they don't see value in doing so? This question needs to be addressed if an effective inclusion strategy is to be developed.

The second message is that the process of financial inclusion is going to be incomplete and inadequate if it is measured only in terms of new accounts being opened and operated. From the employment and earning patterns, there emerged a sense that better access to various kinds of financial services would help to increase the livelihood potential of a number of occupational categories, which in turn would help reduce the income differentials between these and more regular, salaried jobs. The fact that a huge proportion of the Indian workforce is either self-employed and in the casual labour segment suggests the need for products that will make access to credit easier to the former, while offering opportunities for risk mitigation and consumption smoothing to the latter.

The third message emerges from the analysis of expenditure patterns is the significance of infrequent, but quantitatively significant expenditures like ceremonies and medical costs. Essentially, dealing with these kinds of expenditures requires either low-cost insurance options, supported by a correspondingly low-cost health care system or a low level systematic investment plan, which allows even poor households to create enough of a buffer to deal with these demands as and when they arise. As has already been pointed out, it is not as though such products are not being offered by domestic financial service providers. It is really a matter of extending them to make them accessible to a very large number of lower income households, with a low and possibly uncertain ability to maintain regular contributions.

The fourth message comes strongly from the motivations to both save and borrow, which, as one might reasonably expect, significantly overlap with each other. It is striking that the need to deal with emergencies, both financial and medical, plays such an important role in both sets of motivations. The latter is, as has been said, amenable to a low-coat mass insurance scheme, with the attendant service provision. However, the former, which is a theme that recurs through the entire discussion on consumer characteristics, certainly suggests that the need for some kind of income and consumption smoothing product is a significant one in an effective financial inclusion agenda. This, of course, raises broader questions about the role of social safety nets, which offer at least some minimum income security and consumption smoothing. How extensive these mechanisms should be, how much security they should offer and for how long and how they should be financed are fundamental policy questions that go beyond the realm of the financial sector. However, to the extent that risk mitigation is a significant financial need, it must receive due attention of any meaningful financial inclusion strategy, in a way which provides practical answers to all these three questions.

The fifth and final message is actually the point I began the lecture with. It is the critical importance of the principle of commercial viability. Every aspect of a financial inclusion strategy - whether it is the design of products and services or the delivery mechanism -needs to be viewed in terms of the business opportunity that it offers and not as a deliverable that has been imposed on the service provider. However, it is also important to emphasize that commercial viability need not necessarily be viewed in terms of immediate cost and profitability calculations. Like in many other products, financial services also offer the prospect of a life-cycle model of marketing. Establishing a relationship with first-time consumers of financial products and services offers the opportunity to leverage this relationship into a wider set of financial transactions as at least some of these consumers move steadily up the income ladder. In fact, in a high growth scenario, a high proportion of such households are likely to move quite quickly from very basic financial services to more and more sophisticated ones. In other words, the commercial viability and profitability of a financial inclusion strategy need not be viewed only from the perspective of immediacy. There is a viable investment dimension to it as well.

Q. Which of the following statements is incorrect?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I have tried to introduce into the discussion a number of attributes of consumer behaviour and motivations, which I believe are important inputs into devising a strategy for commercially viable financial inclusion. These related broadly to the (i) the sources of livelihood of the potential consumer segment for financial inclusion (ii) how they spend their money, particularly on non-regular items (iii) their choices and motivations with respect to saving and (iv) their motivations for borrowing and their ability to access institutional sources of finance for their basic requirements. In discussing each of these sets of issues, I spent some time drawing implications for business strategies by financial service providers. In this section, I wilt briefly highlight, at the risk of some repetition, what I consider to be the key messages of the lecture.

The first message emerges from the preliminary discussion on the current scenario on financial inclusion, both at the aggregate level and across income categories. The data suggest that even savings accounts, the most basic financial service, have low penetration amongst the lowest income households. I want to emphasize that we are not talking about Below Poverty Line households only; Rs. 50,000 per year in 2007, while perhaps not quite middle class, was certainly quite far above the official poverty line. The same concerns about lack of penetration amongst the lowest income group for loans also arise. To reiterate the question that arises from these data patterns: is this because people can't access banks or other service providers or because they don't see value in doing so? This question needs to be addressed if an effective inclusion strategy is to be developed.

The second message is that the process of financial inclusion is going to be incomplete and inadequate if it is measured only in terms of new accounts being opened and operated. From the employment and earning patterns, there emerged a sense that better access to various kinds of financial services would help to increase the livelihood potential of a number of occupational categories, which in turn would help reduce the income differentials between these and more regular, salaried jobs. The fact that a huge proportion of the Indian workforce is either self-employed and in the casual labour segment suggests the need for products that will make access to credit easier to the former, while offering opportunities for risk mitigation and consumption smoothing to the latter.

The third message emerges from the analysis of expenditure patterns is the significance of infrequent, but quantitatively significant expenditures like ceremonies and medical costs. Essentially, dealing with these kinds of expenditures requires either low-cost insurance options, supported by a correspondingly low-cost health care system or a low level systematic investment plan, which allows even poor households to create enough of a buffer to deal with these demands as and when they arise. As has already been pointed out, it is not as though such products are not being offered by domestic financial service providers. It is really a matter of extending them to make them accessible to a very large number of lower income households, with a low and possibly uncertain ability to maintain regular contributions.

The fourth message comes strongly from the motivations to both save and borrow, which, as one might reasonably expect, significantly overlap with each other. It is striking that the need to deal with emergencies, both financial and medical, plays such an important role in both sets of motivations. The latter is, as has been said, amenable to a low-coat mass insurance scheme, with the attendant service provision. However, the former, which is a theme that recurs through the entire discussion on consumer characteristics, certainly suggests that the need for some kind of income and consumption smoothing product is a significant one in an effective financial inclusion agenda. This, of course, raises broader questions about the role of social safety nets, which offer at least some minimum income security and consumption smoothing. How extensive these mechanisms should be, how much security they should offer and for how long and how they should be financed are fundamental policy questions that go beyond the realm of the financial sector. However, to the extent that risk mitigation is a significant financial need, it must receive due attention of any meaningful financial inclusion strategy, in a way which provides practical answers to all these three questions.

The fifth and final message is actually the point I began the lecture with. It is the critical importance of the principle of commercial viability. Every aspect of a financial inclusion strategy - whether it is the design of products and services or the delivery mechanism -needs to be viewed in terms of the business opportunity that it offers and not as a deliverable that has been imposed on the service provider. However, it is also important to emphasize that commercial viability need not necessarily be viewed in terms of immediate cost and profitability calculations. Like in many other products, financial services also offer the prospect of a life-cycle model of marketing. Establishing a relationship with first-time consumers of financial products and services offers the opportunity to leverage this relationship into a wider set of financial transactions as at least some of these consumers move steadily up the income ladder. In fact, in a high growth scenario, a high proportion of such households are likely to move quite quickly from very basic financial services to more and more sophisticated ones. In other words, the commercial viability and profitability of a financial inclusion strategy need not be viewed only from the perspective of immediacy. There is a viable investment dimension to it as well.

Q. Identify the correct statement from the following:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

I have tried to introduce into the discussion a number of attributes of consumer behaviour and motivations, which I believe are important inputs into devising a strategy for commercially viable financial inclusion. These related broadly to the (i) the sources of livelihood of the potential consumer segment for financial inclusion (ii) how they spend their money, particularly on non-regular items (iii) their choices and motivations with respect to saving and (iv) their motivations for borrowing and their ability to access institutional sources of finance for their basic requirements. In discussing each of these sets of issues, I spent some time drawing implications for business strategies by financial service providers. In this section, I wilt briefly highlight, at the risk of some repetition, what I consider to be the key messages of the lecture.

The first message emerges from the preliminary discussion on the current scenario on financial inclusion, both at the aggregate level and across income categories. The data suggest that even savings accounts, the most basic financial service, have low penetration amongst the lowest income households. I want to emphasize that we are not talking about Below Poverty Line households only; Rs. 50,000 per year in 2007, while perhaps not quite middle class, was certainly quite far above the official poverty line. The same concerns about lack of penetration amongst the lowest income group for loans also arise. To reiterate the question that arises from these data patterns: is this because people can't access banks or other service providers or because they don't see value in doing so? This question needs to be addressed if an effective inclusion strategy is to be developed.

The second message is that the process of financial inclusion is going to be incomplete and inadequate if it is measured only in terms of new accounts being opened and operated. From the employment and earning patterns, there emerged a sense that better access to various kinds of financial services would help to increase the livelihood potential of a number of occupational categories, which in turn would help reduce the income differentials between these and more regular, salaried jobs. The fact that a huge proportion of the Indian workforce is either self-employed and in the casual labour segment suggests the need for products that will make access to credit easier to the former, while offering opportunities for risk mitigation and consumption smoothing to the latter.

The third message emerges from the analysis of expenditure patterns is the significance of infrequent, but quantitatively significant expenditures like ceremonies and medical costs. Essentially, dealing with these kinds of expenditures requires either low-cost insurance options, supported by a correspondingly low-cost health care system or a low level systematic investment plan, which allows even poor households to create enough of a buffer to deal with these demands as and when they arise. As has already been pointed out, it is not as though such products are not being offered by domestic financial service providers. It is really a matter of extending them to make them accessible to a very large number of lower income households, with a low and possibly uncertain ability to maintain regular contributions.

The fourth message comes strongly from the motivations to both save and borrow, which, as one might reasonably expect, significantly overlap with each other. It is striking that the need to deal with emergencies, both financial and medical, plays such an important role in both sets of motivations. The latter is, as has been said, amenable to a low-coat mass insurance scheme, with the attendant service provision. However, the former, which is a theme that recurs through the entire discussion on consumer characteristics, certainly suggests that the need for some kind of income and consumption smoothing product is a significant one in an effective financial inclusion agenda. This, of course, raises broader questions about the role of social safety nets, which offer at least some minimum income security and consumption smoothing. How extensive these mechanisms should be, how much security they should offer and for how long and how they should be financed are fundamental policy questions that go beyond the realm of the financial sector. However, to the extent that risk mitigation is a significant financial need, it must receive due attention of any meaningful financial inclusion strategy, in a way which provides practical answers to all these three questions.

The fifth and final message is actually the point I began the lecture with. It is the critical importance of the principle of commercial viability. Every aspect of a financial inclusion strategy - whether it is the design of products and services or the delivery mechanism -needs to be viewed in terms of the business opportunity that it offers and not as a deliverable that has been imposed on the service provider. However, it is also important to emphasize that commercial viability need not necessarily be viewed in terms of immediate cost and profitability calculations. Like in many other products, financial services also offer the prospect of a life-cycle model of marketing. Establishing a relationship with first-time consumers of financial products and services offers the opportunity to leverage this relationship into a wider set of financial transactions as at least some of these consumers move steadily up the income ladder. In fact, in a high growth scenario, a high proportion of such households are likely to move quite quickly from very basic financial services to more and more sophisticated ones. In other words, the commercial viability and profitability of a financial inclusion strategy need not be viewed only from the perspective of immediacy. There is a viable investment dimension to it as well.

Q. Which of the following statements is correct?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The second issue I want to address is one that comes up frequently - that Indian banks should aim to become global. Most people who put forward this view have not thought through the costs and benefits analytically; they only see this as an aspiration consistent with India's growing international profile. In its 1998 report, the Narasimham (II) Committee envisaged a three tier structure for the Indian banking sector: 3 or 4 large banks having an international presence on the top, 8-10 mid-sized banks, with a network of branches throughout the country and engaged in universal banking, in the middle, and local banks and regional rural banks operating in smaller regions forming the bottom layer. However, the Indian banking system has not consolidated in the manner envisioned by the Narasimham Committee. The current structure is that India has 81 scheduled commercial banks of which 26 are public sector banks. 21 are private sector banks and 34 are foreign banks. Even a quick review would reveal that there is no segmentation in the banking structure along the lines of Narasimham II.

A natural sequel to this issue of the envisaged structure of the Indian banking system is the Reserve Bank's position on bank consolidation. Our view on bank consolidation is that the process should be market-driven, based on profitability considerations and brought about through a process of mergers & amalgamations (M&As). The initiative for this has to come from the boards of the banks concerned which have to make a decision based on a judgment of the synergies involved in the business models and the compatibility of the business cultures. The Reserve Bank's role in the re-organisation of the banking system will normally be only that of a facilitator.

It should-be noted though that bank consolidation through mergers is not always a totally benign option. On the positive side there is a higher exposure threshold, international acceptance and recognition, improved risk management and improvement in financials due to economies of scale and scope. This can be achieved both through organic and inorganic growth. On the negative side, experience shows that consolidation would fail if there are no synergies in the business models and there is no compatibility in the business cultures and technology platforms of the merging banks.

Having given that broad brush position on bank consolidation, let me address two specific questions: (i) can Indian banks aspire to global size and (ii) should Indian banks aspire to global size?

On the first question, as per the current global league tables based on the size of assets, our largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), together with its subsidiaries, comes in at No.74 followed by ICICI Bank at No. 145 and Bank of Baroda at 188. It is, therefore, unlikely that any of our banks will jump into the top ten of the global league even after reasonable consolidation.

Then comes the next question of whether Indian banks should become global. Opinion on this is divided. Those who argue that, we must go global contend that the issue is not so much the size of our banks in global rankings but of Indian banks having a strong enough global presence. The main argument is that the increasing global size and influence of Indian corporates warrant a corresponding increase in the global footprint of Indian banks. The opposing view is that Indian banks should look inwards rather than outwards, focus their efforts on financial deepening at home rather than aspiring to global size.

It is possible to make a middle path and argue that looking outwards towards increased global presence and looking inwards towards deeper financial penetration are not mutually exclusive; it should be possible to aim for both. With the onset of the global financial crisis, there has definitely been a pause to the rapid expansion overseas of our banks. Nevertheless, notwithstanding the risks involved, it will be opportune for some of our larger banks to be looking out for opportunities for consolidation both organically and inorganically. They should look out more actively in regions which hold out a promise of attractive acquisitions.

The surmise, therefore, is that Indian banks should increase their global footprint opportunistically even if they do not get to the top of the league table.

Q. Identify the correct statement from the following:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The second issue I want to address is one that comes up frequently - that Indian banks should aim to become global. Most people who put forward this view have not thought through the costs and benefits analytically; they only see this as an aspiration consistent with India's growing international profile. In its 1998 report, the Narasimham (II) Committee envisaged a three tier structure for the Indian banking sector: 3 or 4 large banks having an international presence on the top, 8-10 mid-sized banks, with a network of branches throughout the country and engaged in universal banking, in the middle, and local banks and regional rural banks operating in smaller regions forming the bottom layer. However, the Indian banking system has not consolidated in the manner envisioned by the Narasimham Committee. The current structure is that India has 81 scheduled commercial banks of which 26 are public sector banks. 21 are private sector banks and 34 are foreign banks. Even a quick review would reveal that there is no segmentation in the banking structure along the lines of Narasimham II.

A natural sequel to this issue of the envisaged structure of the Indian banking system is the Reserve Bank's position on bank consolidation. Our view on bank consolidation is that the process should be market-driven, based on profitability considerations and brought about through a process of mergers & amalgamations (M&As). The initiative for this has to come from the boards of the banks concerned which have to make a decision based on a judgment of the synergies involved in the business models and the compatibility of the business cultures. The Reserve Bank's role in the re-organisation of the banking system will normally be only that of a facilitator.

It should-be noted though that bank consolidation through mergers is not always a totally benign option. On the positive side there is a higher exposure threshold, international acceptance and recognition, improved risk management and improvement in financials due to economies of scale and scope. This can be achieved both through organic and inorganic growth. On the negative side, experience shows that consolidation would fail if there are no synergies in the business models and there is no compatibility in the business cultures and technology platforms of the merging banks.

Having given that broad brush position on bank consolidation, let me address two specific questions: (i) can Indian banks aspire to global size and (ii) should Indian banks aspire to global size?

On the first question, as per the current global league tables based on the size of assets, our largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), together with its subsidiaries, comes in at No.74 followed by ICICI Bank at No. 145 and Bank of Baroda at 188. It is, therefore, unlikely that any of our banks will jump into the top ten of the global league even after reasonable consolidation.

Then comes the next question of whether Indian banks should become global. Opinion on this is divided. Those who argue that, we must go global contend that the issue is not so much the size of our banks in global rankings but of Indian banks having a strong enough global presence. The main argument is that the increasing global size and influence of Indian corporates warrant a corresponding increase in the global footprint of Indian banks. The opposing view is that Indian banks should look inwards rather than outwards, focus their efforts on financial deepening at home rather than aspiring to global size.

It is possible to make a middle path and argue that looking outwards towards increased global presence and looking inwards towards deeper financial penetration are not mutually exclusive; it should be possible to aim for both. With the onset of the global financial crisis, there has definitely been a pause to the rapid expansion overseas of our banks. Nevertheless, notwithstanding the risks involved, it will be opportune for some of our larger banks to be looking out for opportunities for consolidation both organically and inorganically. They should look out more actively in regions which hold out a promise of attractive acquisitions.

The surmise, therefore, is that Indian banks should increase their global footprint opportunistically even if they do not get to the top of the league table.

Q. Identify the correct statement from the following:

Directions: Read the passage and answer the question based on it.

The second issue I want to address is one that comes up frequently - that Indian banks should aim to become global. Most people who put forward this view have not thought through the costs and benefits analytically; they only see this as an aspiration consistent with India's growing international profile. In its 1998 report, the Narasimham (II) Committee envisaged a three tier structure for the Indian banking sector: 3 or 4 large banks having an international presence on the top, 8-10 mid-sized banks, with a network of branches throughout the country and engaged in universal banking, in the middle, and local banks and regional rural banks operating in smaller regions forming the bottom layer. However, the Indian banking system has not consolidated in the manner envisioned by the Narasimham Committee. The current structure is that India has 81 scheduled commercial banks of which 26 are public sector banks. 21 are private sector banks and 34 are foreign banks. Even a quick review would reveal that there is no segmentation in the banking structure along the lines of Narasimham II.

A natural sequel to this issue of the envisaged structure of the Indian banking system is the Reserve Bank's position on bank consolidation. Our view on bank consolidation is that the process should be market-driven, based on profitability considerations and brought about through a process of mergers & amalgamations (M&As). The initiative for this has to come from the boards of the banks concerned which have to make a decision based on a judgment of the synergies involved in the business models and the compatibility of the business cultures. The Reserve Bank's role in the re-organisation of the banking system will normally be only that of a facilitator.

It should-be noted though that bank consolidation through mergers is not always a totally benign option. On the positive side there is a higher exposure threshold, international acceptance and recognition, improved risk management and improvement in financials due to economies of scale and scope. This can be achieved both through organic and inorganic growth. On the negative side, experience shows that consolidation would fail if there are no synergies in the business models and there is no compatibility in the business cultures and technology platforms of the merging banks.

Having given that broad brush position on bank consolidation, let me address two specific questions: (i) can Indian banks aspire to global size and (ii) should Indian banks aspire to global size?

On the first question, as per the current global league tables based on the size of assets, our largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), together with its subsidiaries, comes in at No.74 followed by ICICI Bank at No. 145 and Bank of Baroda at 188. It is, therefore, unlikely that any of our banks will jump into the top ten of the global league even after reasonable consolidation.

Then comes the next question of whether Indian banks should become global. Opinion on this is divided. Those who argue that, we must go global contend that the issue is not so much the size of our banks in global rankings but of Indian banks having a strong enough global presence. The main argument is that the increasing global size and influence of Indian corporates warrant a corresponding increase in the global footprint of Indian banks. The opposing view is that Indian banks should look inwards rather than outwards, focus their efforts on financial deepening at home rather than aspiring to global size.

It is possible to make a middle path and argue that looking outwards towards increased global presence and looking inwards towards deeper financial penetration are not mutually exclusive; it should be possible to aim for both. With the onset of the global financial crisis, there has definitely been a pause to the rapid expansion overseas of our banks. Nevertheless, notwithstanding the risks involved, it will be opportune for some of our larger banks to be looking out for opportunities for consolidation both organically and inorganically. They should look out more actively in regions which hold out a promise of attractive acquisitions.

The surmise, therefore, is that Indian banks should increase their global footprint opportunistically even if they do not get to the top of the league table.

Q. Which one of the following is the most appropriate meaning of the bold word of the paragraph?