IIFT Mock Test - 7 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 7 (New Pattern)

Read the following sets of four sentences and arrange them in the most logical sequence to form a meaningful and coherent paragraph.

I. A millennium in which Europe had been the political center of the world came to a crashing halt.

II. When war ended four years later, Europe lay in ruins: the kaiser gone, the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved, the Russian tsar overthrown by the Bolsheviks, France bled for a generation, and England shorn of its youth and treasure.

III. In 1914, few could imagine slaughter on a scale that demanded a new category: world war.

IV. When we say that war is "inconceivable," is this a statement about what is possible in the world - or only about what our limited minds can conceive?

Which of the following options has both words spelled correctly?

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Fill in the blanks with the most appropriate option.

The members of the football team were __________ by the presence of a female reporter in the locker room.

For the underlines part of the give sentence, choose the option that is grammatically correct, effective and reduces ambiguity and redundancy.

Wisconsin, Illinois, Florida, and Minnesota have begun to enforce statewide bans prohibiting landfills to accept leaves, brush, and grass clippings.

Select the option which expresses a relationship similar to the one expressed in the capitalized pair.

ECLAT : PANACHE

The first and last part of a sentence are marked 1 and 6. The rest of the sentence is split into 5 parts and marked i, ii, iii, iv and v. These five parts are not given in their proper order. From the options given, please choose the most appropriate order to form a coherent, logical and grammatically correct sentence.

1. Just as a,

(i) so there might be an

(ii) pixel is the smallest unit

(iii) of an image on your screen

(iv) unbreakable smallest unit

(v) of distance :

6. a quantum space

Select the option which is grammatically correct.

Fill in the blanks with the word or phrase that completes the idiom correctly in the given sentences.

I cannot put _____ his insolence anymore.

Read the following sets of four sentences and arrange them in the most logical sequence to form a meaningful and coherent paragraph.

I. Unlike the parlor tricks of the deconstructionists who bloviate about difference and traces, there clearly are rules that shouldn't be broken and clearly ways of speaking that are blatantly incorrect, even if they change over time and admit to flexible interpretations even on a daily basis.

II. So, language is quicksand - except it's not.

III. It's just that explicitly delineating those boundaries is extremely difficult, because language is not built up through organized, hierarchical rules but from the top down through byzantine, overlapping practices.

IV. Some things can be pinned down with practical certainty, just not in isolation and without context.

Which of the following words is spelled correctly?

Fill in the blanks with the most appropriate option.

A member of the bourgeoisie might purchase a vacation home on Maui or Cape God that some would regard as an ___________ display of wealth.

For the underlines part of the give sentence, choose the option that is grammatically correct, effective and reduces ambiguity and redundancy.

Geologists believe that the warning signs for a major earthquake may include sudden fluctuations in local seismic activity, tilting and other deformations of the Earth's crust, changing the measured strain across a fault zone, and varying the electrical properties of underground rocks.

Select the option which expresses a relationship similar to the one expressed in the capitalized pair.

CORNUCOPIA : PLENTITUDE

The first and last part of a sentence are marked 1 and 6. The rest of the sentence is split into 5 parts and marked i, ii, iii, iv and v. These five parts are not given in their proper order. From the options given, please choose the most appropriate order to form a coherent, logical and grammatically correct sentence.

1. And there is

i. the seeds of religious doubt are

ii. that one of the key collateral benefits

iii. of a more scientifically

iv. literate populace is that

v. overwhelming evidence

6. thereby planted among the next generation

Select the option which is grammatically correct.

Fill in the blanks with the word or phrase that completes the idiom correctly in the given sentences.

I thought we were going bankrupt, but he ___________and we landed a major contract.

Find one word for the given sentence:

Handwriting which is not clear enough to be read.

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

You don't forget meeting Sheila Kitzinger. When I did two years ago, the gathered crowd of midwives, doctors and doulas practically stopped breathing for a moment as she entered the room. She was more than a hero to every pair of eyes that followed her stately progress to the stage. Resplendent in magenta, with a trademark feather in her hair, she spoke, in a voice that seemed made for rousing battle cries, about birth and sex until the young cameramen present were blushing deep scarlet. They shifted uncomfortably as she described "nipples becoming erect" in her characteristic, resonant tones.

Here was a woman, in her 80s no less, unafraid to confront the complexities of female sexuality on a daily basis. The world needs reminding of these all too regularly and for the past 50 or more years we've had Kitzinger there to do just that.

When I heard of her death I looked through my bookshelf, which is punctuated with her many books. Most striking is a painfully yellow booklet, Episiotomy: Physical and Emotional Aspects, published in 1981. It was written at a time when over half of UK women (and a much higher proportion of first-time mothers) were cut through the perineum during childbirth on the basis of little more than a ritualised obstetric whim.

In Episiotomy, Kitzinger is revolutionary in reminding those in the maternity services that "the feelings a woman has in labour cannot really be considered in isolation from other psychosexual aspects of her life". That an operation on her genitals might impact on a woman beyond that moment of birth, and the detailing of how and why that might be, is reflective of the kind of work she did best. Her research and campaigning on this issue made a significant contribution to vastly reducing its use. Though 75% of women in Cyprus still get routinely cut during childbirth, less than 20% of UK women do.

Kitzinger's work has been so wide-ranging and powerful that it is impossible to round it up briefly. For me, though, what unites her 30 books, many papers and wide-ranging commentary is her eloquent insistence that women's experiences through pregnancy and parenting matter: during birth, yes, but crucially beyond that day, too. Prompted by a 20th-century maternity system that had increasingly turned childbirth into something that was done to women with a sterile barbarity, Kitzinger was relentless in her insistence that women needed to be put back at the centre of childbirth.

Many of the tributes to Kitzinger today use phrases such as "natural childbirth pioneer". Of course, much of her work can be pigeon-holed that way if you want. But how quickly and easily the power of any discussion around childbirth is halved by doing just that. And she was interested in understanding the way women experienced birth without unnecessary interference, perhaps because she listened to women, many of whom understandably said they weren't too keen on being routinely shaved, given an enema, drugged, cut and set about with forceps. But Kitzinger was no pusher of birth ideology.

She studied women and their real-life experiences, listening attentively as those changed over the decades. Her Birth Crisis helpline, often answered by Kitzinger herself, offered over-the-phone counselling to women who wanted to talk about their traumatic births. With all those divergent voices in her ears, she couldn't reduce her message to a simple doctrine. She knew, and was not afraid to say, that the natural birth movement is problematic, too. In 2013 she said that she felt women were under pressure to "perform" during birth, to demonstrate all they had learned in their antenatal classes, and that birth had "become too goal-orientated". The word "natural" was one she felt was far too nuanced to use as an epithet synonymous with "good". In fact, she said that we need to question "the idea that nature is always best".

Q. Which of the following statements, according to the author, Sheila Kitzinger was most likely to agree with?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

You don't forget meeting Sheila Kitzinger. When I did two years ago, the gathered crowd of midwives, doctors and doulas practically stopped breathing for a moment as she entered the room. She was more than a hero to every pair of eyes that followed her stately progress to the stage. Resplendent in magenta, with a trademark feather in her hair, she spoke, in a voice that seemed made for rousing battle cries, about birth and sex until the young cameramen present were blushing deep scarlet. They shifted uncomfortably as she described "nipples becoming erect" in her characteristic, resonant tones.

Here was a woman, in her 80s no less, unafraid to confront the complexities of female sexuality on a daily basis. The world needs reminding of these all too regularly and for the past 50 or more years we've had Kitzinger there to do just that.

When I heard of her death I looked through my bookshelf, which is punctuated with her many books. Most striking is a painfully yellow booklet, Episiotomy: Physical and Emotional Aspects, published in 1981. It was written at a time when over half of UK women (and a much higher proportion of first-time mothers) were cut through the perineum during childbirth on the basis of little more than a ritualised obstetric whim.

In Episiotomy, Kitzinger is revolutionary in reminding those in the maternity services that "the feelings a woman has in labour cannot really be considered in isolation from other psychosexual aspects of her life". That an operation on her genitals might impact on a woman beyond that moment of birth, and the detailing of how and why that might be, is reflective of the kind of work she did best. Her research and campaigning on this issue made a significant contribution to vastly reducing its use. Though 75% of women in Cyprus still get routinely cut during childbirth, less than 20% of UK women do.

Kitzinger's work has been so wide-ranging and powerful that it is impossible to round it up briefly. For me, though, what unites her 30 books, many papers and wide-ranging commentary is her eloquent insistence that women's experiences through pregnancy and parenting matter: during birth, yes, but crucially beyond that day, too. Prompted by a 20th-century maternity system that had increasingly turned childbirth into something that was done to women with a sterile barbarity, Kitzinger was relentless in her insistence that women needed to be put back at the centre of childbirth.

Many of the tributes to Kitzinger today use phrases such as "natural childbirth pioneer". Of course, much of her work can be pigeon-holed that way if you want. But how quickly and easily the power of any discussion around childbirth is halved by doing just that. And she was interested in understanding the way women experienced birth without unnecessary interference, perhaps because she listened to women, many of whom understandably said they weren't too keen on being routinely shaved, given an enema, drugged, cut and set about with forceps. But Kitzinger was no pusher of birth ideology.

She studied women and their real-life experiences, listening attentively as those changed over the decades. Her Birth Crisis helpline, often answered by Kitzinger herself, offered over-the-phone counselling to women who wanted to talk about their traumatic births. With all those divergent voices in her ears, she couldn't reduce her message to a simple doctrine. She knew, and was not afraid to say, that the natural birth movement is problematic, too. In 2013 she said that she felt women were under pressure to "perform" during birth, to demonstrate all they had learned in their antenatal classes, and that birth had "become too goal-orientated". The word "natural" was one she felt was far too nuanced to use as an epithet synonymous with "good". In fact, she said that we need to question "the idea that nature is always best".

Q. Which of the following statements is correct ?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

You don't forget meeting Sheila Kitzinger. When I did two years ago, the gathered crowd of midwives, doctors and doulas practically stopped breathing for a moment as she entered the room. She was more than a hero to every pair of eyes that followed her stately progress to the stage. Resplendent in magenta, with a trademark feather in her hair, she spoke, in a voice that seemed made for rousing battle cries, about birth and sex until the young cameramen present were blushing deep scarlet. They shifted uncomfortably as she described "nipples becoming erect" in her characteristic, resonant tones.

Here was a woman, in her 80s no less, unafraid to confront the complexities of female sexuality on a daily basis. The world needs reminding of these all too regularly and for the past 50 or more years we've had Kitzinger there to do just that.

When I heard of her death I looked through my bookshelf, which is punctuated with her many books. Most striking is a painfully yellow booklet, Episiotomy: Physical and Emotional Aspects, published in 1981. It was written at a time when over half of UK women (and a much higher proportion of first-time mothers) were cut through the perineum during childbirth on the basis of little more than a ritualised obstetric whim.

In Episiotomy, Kitzinger is revolutionary in reminding those in the maternity services that "the feelings a woman has in labour cannot really be considered in isolation from other psychosexual aspects of her life". That an operation on her genitals might impact on a woman beyond that moment of birth, and the detailing of how and why that might be, is reflective of the kind of work she did best. Her research and campaigning on this issue made a significant contribution to vastly reducing its use. Though 75% of women in Cyprus still get routinely cut during childbirth, less than 20% of UK women do.

Kitzinger's work has been so wide-ranging and powerful that it is impossible to round it up briefly. For me, though, what unites her 30 books, many papers and wide-ranging commentary is her eloquent insistence that women's experiences through pregnancy and parenting matter: during birth, yes, but crucially beyond that day, too. Prompted by a 20th-century maternity system that had increasingly turned childbirth into something that was done to women with a sterile barbarity, Kitzinger was relentless in her insistence that women needed to be put back at the centre of childbirth.

Many of the tributes to Kitzinger today use phrases such as "natural childbirth pioneer". Of course, much of her work can be pigeon-holed that way if you want. But how quickly and easily the power of any discussion around childbirth is halved by doing just that. And she was interested in understanding the way women experienced birth without unnecessary interference, perhaps because she listened to women, many of whom understandably said they weren't too keen on being routinely shaved, given an enema, drugged, cut and set about with forceps. But Kitzinger was no pusher of birth ideology.

She studied women and their real-life experiences, listening attentively as those changed over the decades. Her Birth Crisis helpline, often answered by Kitzinger herself, offered over-the-phone counselling to women who wanted to talk about their traumatic births. With all those divergent voices in her ears, she couldn't reduce her message to a simple doctrine. She knew, and was not afraid to say, that the natural birth movement is problematic, too. In 2013 she said that she felt women were under pressure to "perform" during birth, to demonstrate all they had learned in their antenatal classes, and that birth had "become too goal-orientated". The word "natural" was one she felt was far too nuanced to use as an epithet synonymous with "good". In fact, she said that we need to question "the idea that nature is always best".

Q. According to the passage, Sheila Kitzinger can be best described as ?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

You don't forget meeting Sheila Kitzinger. When I did two years ago, the gathered crowd of midwives, doctors and doulas practically stopped breathing for a moment as she entered the room. She was more than a hero to every pair of eyes that followed her stately progress to the stage. Resplendent in magenta, with a trademark feather in her hair, she spoke, in a voice that seemed made for rousing battle cries, about birth and sex until the young cameramen present were blushing deep scarlet. They shifted uncomfortably as she described "nipples becoming erect" in her characteristic, resonant tones.

Here was a woman, in her 80s no less, unafraid to confront the complexities of female sexuality on a daily basis. The world needs reminding of these all too regularly and for the past 50 or more years we've had Kitzinger there to do just that.

When I heard of her death I looked through my bookshelf, which is punctuated with her many books. Most striking is a painfully yellow booklet, Episiotomy: Physical and Emotional Aspects, published in 1981. It was written at a time when over half of UK women (and a much higher proportion of first-time mothers) were cut through the perineum during childbirth on the basis of little more than a ritualised obstetric whim.

In Episiotomy, Kitzinger is revolutionary in reminding those in the maternity services that "the feelings a woman has in labour cannot really be considered in isolation from other psychosexual aspects of her life". That an operation on her genitals might impact on a woman beyond that moment of birth, and the detailing of how and why that might be, is reflective of the kind of work she did best. Her research and campaigning on this issue made a significant contribution to vastly reducing its use. Though 75% of women in Cyprus still get routinely cut during childbirth, less than 20% of UK women do.

Kitzinger's work has been so wide-ranging and powerful that it is impossible to round it up briefly. For me, though, what unites her 30 books, many papers and wide-ranging commentary is her eloquent insistence that women's experiences through pregnancy and parenting matter: during birth, yes, but crucially beyond that day, too. Prompted by a 20th-century maternity system that had increasingly turned childbirth into something that was done to women with a sterile barbarity, Kitzinger was relentless in her insistence that women needed to be put back at the centre of childbirth.

Many of the tributes to Kitzinger today use phrases such as "natural childbirth pioneer". Of course, much of her work can be pigeon-holed that way if you want. But how quickly and easily the power of any discussion around childbirth is halved by doing just that. And she was interested in understanding the way women experienced birth without unnecessary interference, perhaps because she listened to women, many of whom understandably said they weren't too keen on being routinely shaved, given an enema, drugged, cut and set about with forceps. But Kitzinger was no pusher of birth ideology.

She studied women and their real-life experiences, listening attentively as those changed over the decades. Her Birth Crisis helpline, often answered by Kitzinger herself, offered over-the-phone counselling to women who wanted to talk about their traumatic births. With all those divergent voices in her ears, she couldn't reduce her message to a simple doctrine. She knew, and was not afraid to say, that the natural birth movement is problematic, too. In 2013 she said that she felt women were under pressure to "perform" during birth, to demonstrate all they had learned in their antenatal classes, and that birth had "become too goal-orientated". The word "natural" was one she felt was far too nuanced to use as an epithet synonymous with "good". In fact, she said that we need to question "the idea that nature is always best".

Q. Which of the following, according to the author, helped Sheila Kitzinger to broaden the scope of her message to the society for the welfare of women?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

You don't forget meeting Sheila Kitzinger. When I did two years ago, the gathered crowd of midwives, doctors and doulas practically stopped breathing for a moment as she entered the room. She was more than a hero to every pair of eyes that followed her stately progress to the stage. Resplendent in magenta, with a trademark feather in her hair, she spoke, in a voice that seemed made for rousing battle cries, about birth and sex until the young cameramen present were blushing deep scarlet. They shifted uncomfortably as she described "nipples becoming erect" in her characteristic, resonant tones.

Here was a woman, in her 80s no less, unafraid to confront the complexities of female sexuality on a daily basis. The world needs reminding of these all too regularly and for the past 50 or more years we've had Kitzinger there to do just that.

When I heard of her death I looked through my bookshelf, which is punctuated with her many books. Most striking is a painfully yellow booklet, Episiotomy: Physical and Emotional Aspects, published in 1981. It was written at a time when over half of UK women (and a much higher proportion of first-time mothers) were cut through the perineum during childbirth on the basis of little more than a ritualised obstetric whim.

In Episiotomy, Kitzinger is revolutionary in reminding those in the maternity services that "the feelings a woman has in labour cannot really be considered in isolation from other psychosexual aspects of her life". That an operation on her genitals might impact on a woman beyond that moment of birth, and the detailing of how and why that might be, is reflective of the kind of work she did best. Her research and campaigning on this issue made a significant contribution to vastly reducing its use. Though 75% of women in Cyprus still get routinely cut during childbirth, less than 20% of UK women do.

Kitzinger's work has been so wide-ranging and powerful that it is impossible to round it up briefly. For me, though, what unites her 30 books, many papers and wide-ranging commentary is her eloquent insistence that women's experiences through pregnancy and parenting matter: during birth, yes, but crucially beyond that day, too. Prompted by a 20th-century maternity system that had increasingly turned childbirth into something that was done to women with a sterile barbarity, Kitzinger was relentless in her insistence that women needed to be put back at the centre of childbirth.

Many of the tributes to Kitzinger today use phrases such as "natural childbirth pioneer". Of course, much of her work can be pigeon-holed that way if you want. But how quickly and easily the power of any discussion around childbirth is halved by doing just that. And she was interested in understanding the way women experienced birth without unnecessary interference, perhaps because she listened to women, many of whom understandably said they weren't too keen on being routinely shaved, given an enema, drugged, cut and set about with forceps. But Kitzinger was no pusher of birth ideology.

She studied women and their real-life experiences, listening attentively as those changed over the decades. Her Birth Crisis helpline, often answered by Kitzinger herself, offered over-the-phone counselling to women who wanted to talk about their traumatic births. With all those divergent voices in her ears, she couldn't reduce her message to a simple doctrine. She knew, and was not afraid to say, that the natural birth movement is problematic, too. In 2013 she said that she felt women were under pressure to "perform" during birth, to demonstrate all they had learned in their antenatal classes, and that birth had "become too goal-orientated". The word "natural" was one she felt was far too nuanced to use as an epithet synonymous with "good". In fact, she said that we need to question "the idea that nature is always best".

Q. Which of the following statements is incorrect?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal mega-fauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed 'vary', and the accompaniment, 'laoka'. The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE. In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam. Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana. The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast. Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and - less commonly - the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century. While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors. Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.

Terraced, irrigated rice paddies emerged in the central highlands around 1600 CE. As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land. By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina. By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century, the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals. Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet. Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575 - 1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.

Why, according to the passage, were fresh zebu milk and curds constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal mega-fauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed 'vary', and the accompaniment, 'laoka'. The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE. In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam. Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana. The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast. Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and - less commonly - the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century. While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors. Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.

Terraced, irrigated rice paddies emerged in the central highlands around 1600 CE. As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land. By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina. By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century, the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals. Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet. Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575 - 1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.

All of the following were the responsibilities of the 'Manhattan Project' EXCEPT :

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal mega-fauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed 'vary', and the accompaniment, 'laoka'. The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE. In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam. Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana. The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast. Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and - less commonly - the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century. While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors. Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.

Terraced, irrigated rice paddies emerged in the central highlands around 1600 CE. As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land. By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina. By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century, the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals. Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet. Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575 - 1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.

Q. Which of the following is an odd one out, according to the passage?

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal mega-fauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed 'vary', and the accompaniment, 'laoka'. The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE. In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam. Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana. The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast. Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and - less commonly - the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century. While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors. Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.

Terraced, irrigated rice paddies emerged in the central highlands around 1600 CE. As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land. By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina. By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century, the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals. Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet. Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575 - 1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.

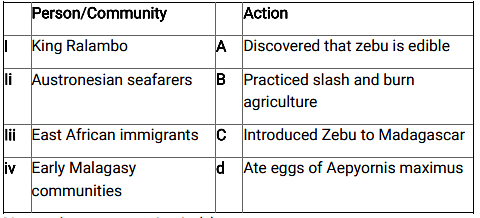

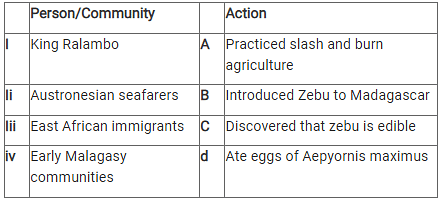

Match the following

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal mega-fauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE. Trade with Arab and Indian merchants and European transatlantic traders further enriched the island's culinary traditions by introducing a wealth of new fruits, vegetables and seasonings.

Throughout almost the entire island, the contemporary cuisine of Madagascar typically consists of a base of rice served with an accompaniment; in the official dialect of the Malagasy language, the rice is termed 'vary', and the accompaniment, 'laoka'. The many varieties of laoka may be vegetarian or include animal proteins, and typically feature a sauce flavored with such ingredients as ginger, onion, garlic, tomato, vanilla, salt, curry powder, or, less commonly, other spices or herbs. In parts of the arid south and west, pastoral families may replace rice with maize, cassava, or curds made from fermented zebu milk. A wide variety of sweet and savory fritters as well as other street foods are available across the island, as are diverse tropical and temperate-climate fruits. Locally produced beverages include fruit juices, coffee, herbal teas and teas, and alcoholic drinks such as rum, wine and beer.

The range of dishes eaten in Madagascar in the 21st century offers insight into the island's unique history and the diversity of the peoples who inhabit it today. The complexity of Malagasy meals can range from the simple, traditional preparations introduced by the earliest settlers, to the refined festival dishes prepared for the island's 19th-century monarchs. Although the classic Malagasy meal of rice and its accompaniment remains predominant, over the past 100 years other food types and combinations have been popularized by French colonists and immigrants from China and India. Consequently, Malagasy cuisine is traditional while also assimilating newly emergent cultural influences.

Austronesian seafarers are believed to have been the first humans to settle on the island, arriving between 100 and 500 CE. In their outrigger canoes they carried food staples from home including rice, plantains, taro, and water yam. Sugarcane, ginger, sweet potatoes, pigs and chickens were also probably brought to Madagascar by these first settlers, along with coconut and banana. The first concentrated population of human settlers emerged along the southeastern coast of the island, although the first landfall may have been made on the northern coast. Upon arrival, early settlers practiced tavy (swidden, "slash-and-burn" agriculture) to clear the virgin coastal rainforests for the cultivation of crops. They also gathered honey, fruits, bird and crocodile eggs, mushrooms, edible seeds and roots, and brewed alcoholic beverages from honey and sugar cane juice.

Game was regularly hunted and trapped in the forests, including frogs, snakes, lizards, hedgehogs and tenrecs, tortoises, wild boars, insects, larvae, birds and lemurs. The first settlers encountered Madagascar's wealth of megafauna, including giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa and the Malagasy hippopotamus. Early Malagasy communities may have eaten the eggs and - less commonly - the meat of Aepyornis maximus, the world's largest bird, which remained widespread throughout Madagascar as recently as the 17th century. While several theories have been proposed to explain the decline and eventual extinction of Malagasy megafauna, clear evidence suggests that hunting by humans and destruction of habitats through slash-and-burn agricultural practices were key factors. Although it has been illegal to hunt or trade any of the remaining species of lemur since 1964, these endangered animals continue to be hunted for immediate local consumption in rural areas or to supply the demand for exotic bush meat at some urban restaurants.

Terraced, irrigated rice paddies emerged in the central highlands around 1600 CE. As more virgin forest was lost to tavy, communities increasingly planted and cultivated permanent plots of land. By 600 CE, groups of these early settlers had moved inland and begun clearing the forests of the central highlands. Rice was originally dry planted or cultivated in marshy lowland areas, which produced low yields. Irrigated rice paddies were adopted in the highlands around 1600, first in Betsileo country in the southern highlands, then later in the northern highlands of Imerina. By the time terraced paddies emerged in central Madagascar over the next century, the area's original forest cover had largely vanished. In its place were scattered villages ringed with nearby rice paddies and crop fields a day's walk away, surrounded by vast plains of sterile grasses.

Zebu, a form of humped cattle, were introduced to the island around 1000 CE by settlers from east Africa, who also brought sorghum, goats, possibly Bambara groundnut, and other food sources. Because these cattle represented a form of wealth in east African and consequently Malagasy culture, they were eaten only rarely, typically after their ritual sacrifice at events of spiritual import such as funerals. Fresh zebu milk and curds instead constituted a major part of the pastoralists' diet. Zebu were kept in large herds in the south and west, but as individual herd members escaped and reproduced, a sizable population of wild zebu established itself in the highlands. Merina oral history tells that highland people were unaware that zebu were edible prior to the reign of King Ralambo (ruled 1575 - 1612), who is credited with the discovery, although archaeological evidence suggests that zebu were occasionally hunted and consumed in the highlands prior to Ralambo's time. It is more likely that these wild herds were first domesticated and kept in pens during this period, which corresponds with the emergence of complex, structured polities in the highlands.

Q. The aim of the 7th paragraph is-

Direction: Read the following passage and answer the following questions.

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project that produced the first nuclear weapons during World War II. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory that designed the actual bombs. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; "Manhattan" gradually superseded the official codename, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion (about $26 billion in 2015 dollars). Over 90% of the cost was for building factories and producing the fissile materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons. Research and production took place at more than 30 sites across the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada.

Two types of atomic bomb were developed during the war. A relatively simple gun-type fission weapon was made using uranium-235, an isotope that makes up only 0.7 percent of natural uranium. Since it is chemically identical to the most common isotope, uranium-238, and has almost the same mass, it proved difficult to separate. Three methods were employed for uranium enrichment: electromagnetic, gaseous and thermal. Most of this work was performed at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. In parallel with the work on uranium was an effort to produce plutonium. Reactors were constructed at Oak Ridge and Hanford, Washington, in which uranium was irradiated and transmuted into plutonium. The plutonium was then chemically separated from the uranium. The gun-type design proved impractical to use with plutonium so a more complex implosion-type weapon was developed in a concerted design and construction effort at the project's principal research and design laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The project was also charged with gathering intelligence on the German nuclear weapon project. Through Operation Alsos, Manhattan Project personnel served in Europe, sometimes behind enemy lines, where they gathered nuclear materials and documents, and rounded up German scientists. Despite the Manhattan Project's tight security, Soviet atomic spies still penetrated the program.

The first nuclear device ever detonated was an implosion-type bomb at the Trinity test, conducted at New Mexico's Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range on 16 July 1945. Little Boy, a gun-type weapon, and Fat Man, an implosion-type weapon, were used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. In the immediate postwar years, the Manhattan Project conducted weapons testing at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads, developed new weapons, promoted the development of the network of national laboratories, supported medical research into radiology and laid the foundations for the nuclear navy. It maintained control over American atomic weapons research and production until the formation of the United States Atomic Energy Commission in January 1947.

The discovery of nuclear fission by German chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938, and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, made the development of an atomic bomb a theoretical possibility. There were fears that a German atomic bomb project would develop one first, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries. In August 1939, physicists Leó Szilárd and Eugene Wigner drafted the Einstein - Szilárd letter, which warned of the potential development of "extremely powerful bombs of a new type". It urged the United States to take steps to acquire stockpiles of uranium ore and accelerate the research of Enrico Fermi and others into nuclear chain reactions. They had it signed by Albert Einstein and delivered to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt called on Lyman Briggs of the National Bureau of Standards to head the Advisory Committee on Uranium to investigate the issues raised by the letter. Briggs held a meeting on 21 October 1939, which was attended by Szilárd, Wigner and Edward Teller. The committee reported back to Roosevelt in November that uranium "would provide a possible source of bombs with destructiveness vastly greater than anything now known."

Briggs proposed that the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) spend $167,000 on research into uranium, particularly the uranium-235 isotope, and the recently discovered plutonium. On 28 June 1941, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8807, which created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), with Vannevar Bush as its director. The office was empowered to engage in large engineering projects in addition to research. The NDRC Committee on Uranium became the S-1 Uranium Committee of the OSRD; the word "uranium" was soon dropped for security reasons.

In Britain, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls at the University of Birmingham had made a breakthrough investigating the critical mass of uranium-235 in June 1939. Their calculations indicated that it was within an order of magnitude of 10 kilograms (22 lb), which was small enough to be carried by a bomber of the day. Their March 1940 Frisch - Peierls memorandum initiated the British atomic bomb project and its Maud Committee, which unanimously recommended pursuing the development of an atomic bomb. In July 1940, Britain had offered to give the United States access to its scientific research, and the Tizard Mission's John Cockcroft briefed American scientists on British developments. He discovered that the American project was smaller than the British, and not as far advanced.

As part of the scientific exchange, the Maud Committee's findings were conveyed to the United States. One of its members, the Australian physicist Mark Oliphant, flew to the United States in late August 1941 and discovered that data provided by the Maud Committee had not reached key American physicists. Oliphant then set out to find out why the committee's findings were apparently being ignored. He met with the Uranium Committee, and visited Berkeley, California, where he spoke persuasively to Ernest O. Lawrence. Lawrence was sufficiently impressed to commence his own research into uranium. He in turn spoke to James B. Conant, Arthur H. Compton and George B. Pegram. Oliphant's mission was therefore a success; key American physicists were now aware of the potential power of an atomic bomb.

At a meeting between President Roosevelt, Vannevar Bush, and Vice President Henry A. Wallace on 9 October 1941, the President approved the atomic program. To control it, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself - although he never attended a meeting - Wallace, Bush, Conant, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall. Roosevelt chose the Army to run the project rather than the Navy, as the Army had the most experience with management of large-scale construction projects. He also agreed to coordinate the effort with that of the British, and on 11 October he sent a message to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, suggesting that they correspond on atomic matters.

Q. Which of the following statements is incorrect?