OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 8 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 8

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. Which choice best summarizes the passage?

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. In line 2, “turn” most nearly means

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. The passage most clearly implies that other peopleregarded Lady Carlotta as

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. The description of how Lady Carlotta “put the doctrine of non-interference into practice” (lines 14-15) mainly serves to

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. In line 55, “charge” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. The narrator indicates that Claude, Wilfrid, Irene, and Viola are

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. The narrator implies that Mrs. Quabarl favors a form of education that emphasizes

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. As presented in the passage, Mrs. Quabarl is best described as

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from Saki, “The Schartz-Metterklume Method.” Originally published in 1911.

Lady Carlotta stepped out on to the platform of

the small wayside station and took a turn or two up

and down its uninteresting length, to kill time till the

train should be pleased to proceed on its way. Then,

(5) in the roadway beyond, she saw a horse struggling

with a more than ample load, and a carter of the sort

that seems to bear a sullen hatred against the animal

that helps him to earn a living. Lady Carlotta

promptly betook her to the roadway, and put rather a

(10) different complexion on the struggle. Certain of her

acquaintances were wont to give her plentiful

admonition as to the undesirability of interfering on

behalf of a distressed animal, such interference being

“none of her business.” Only once had she put the

(15) doctrine of non-interference into practice, when one

of its most eloquent exponents had been besieged for

nearly three hours in a small and extremely

uncomfortable may-tree by an angry boar-pig, while

Lady Carlotta, on the other side of the fence, had

(20) proceeded with the water-colour sketch she was

engaged on, and refused to interfere between the

boar and his prisoner. It is to be feared that she lost

the friendship of the ultimately rescued lady. On this

occasion she merely lost the train, which gave way to

(25) the first sign of impatience it had shown throughout

the journey, and steamed off without her. She bore

the desertion with philosophical indifference; her

friends and relations were thoroughly well used to

the fact of her luggage arriving without her.

(30) She wired a vague non-committal message to her

destination to say that she was coming on “by

another train.” Before she had time to think what her

next move might be she was confronted by an

imposingly attired lady, who seemed to be taking a

(35) prolonged mental inventory of her clothes and looks.

“You must be Miss Hope, the governess I’ve come

to meet,” said the apparition, in a tone that admitted

of very little argument.

“Very well, if I must I must,” said Lady Carlotta to

(40) herself with dangerous meekness.

“I am Mrs. Quabarl,” continued the lady; “and

where, pray, is your luggage?”

“It’s gone astray,” said the alleged governess,

falling in with the excellent rule of life that the absent

(45) are always to blame; the luggage had, in point of fact,

behaved with perfect correctitude. “I’ve just

telegraphed about it,” she added, with a nearer

approach to truth.

“How provoking,” said Mrs. Quabarl; “these

(50) railway companies are so careless. However, my

maid can lend you things for the night,” and she led

the way to her car.

During the drive to the Quabarl mansion

Lady Carlotta was impressively introduced to the

(55) nature of the charge that had been thrust upon her;

she learned that Claude and Wilfrid were delicate,

sensitive young people, that Irene had the artistic

temperament highly developed, and that Viola was

something or other else of a mould equally

(60) commonplace among children of that class and type

in the twentieth century.

“I wish them not only to be TAUGHT,” said Mrs.

Quabarl, “but INTERESTED in what they learn. In

their history lessons, for instance, you must try to

(65) make them feel that they are being introduced to the

life-stories of men and women who really lived, not

merely committing a mass of names and dates to

memory. French, of course, I shall expect you to talk

at meal-times several days in the week.”

(70) “I shall talk French four days of the week and

Russian in the remaining three.”

“Russian? My dear Miss Hope, no one in the

house speaks or understands Russian.”

“That will not embarrass me in the least,” said

(75) Lady Carlotta coldly.

Mrs. Quabarl, to use a colloquial expression, was

knocked off her perch. She was one of those

imperfectly self-assured individuals who are

magnificent and autocratic as long as they are not

(80) seriously opposed. The least show of unexpected

resistance goes a long way towards rendering them

cowed and apologetic. When the new governess

failed to express wondering admiration of the large

newly-purchased and expensive car, and lightly

(85) alluded to the superior advantages of one or two

makes which had just been put on the market, the

discomfiture of her patroness became almost abject.

Her feelings were those which might have animated a

general of ancient warfaring days, on beholding his

(90) heaviest battle-elephant ignominiously driven off the

field by slingers and javelin throwers.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

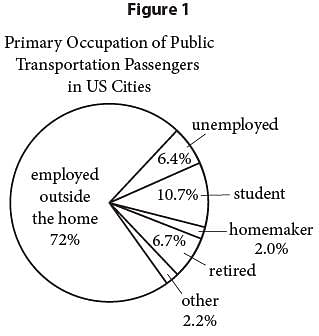

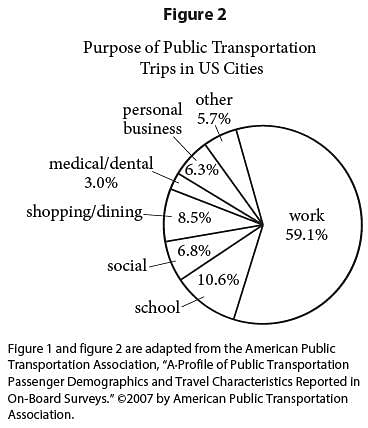

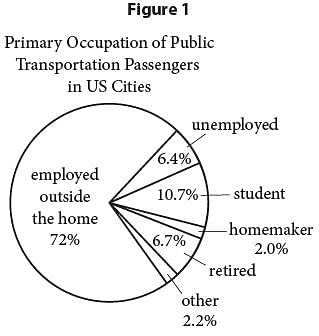

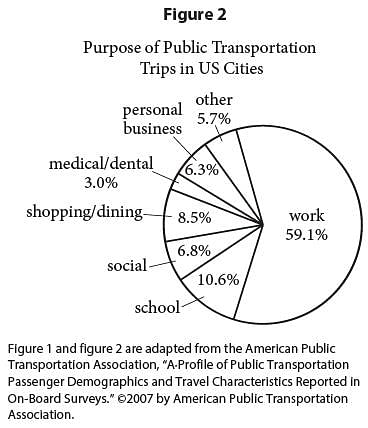

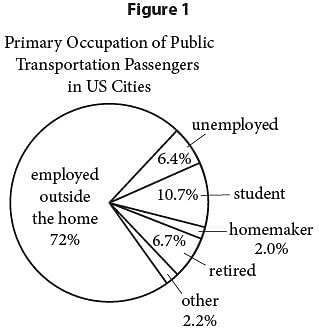

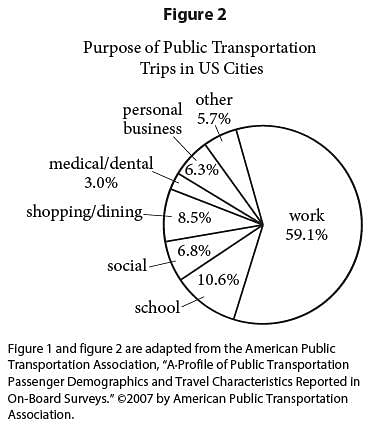

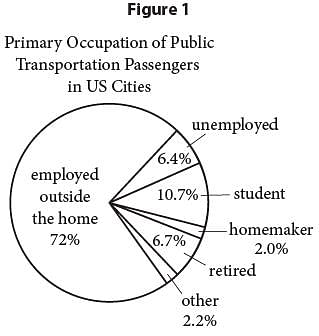

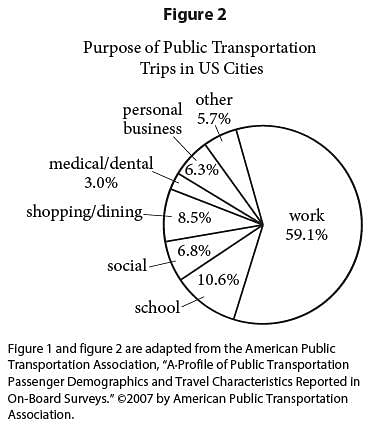

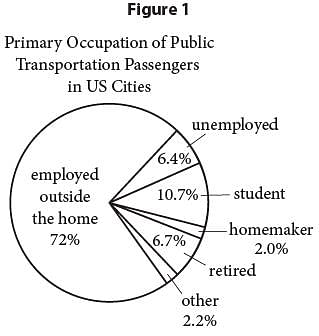

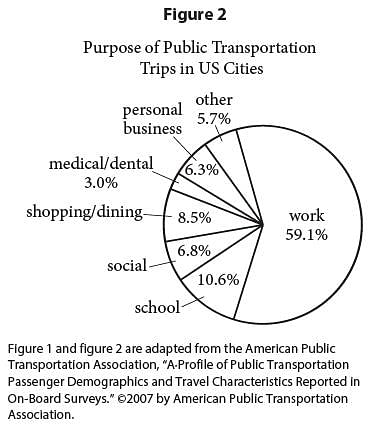

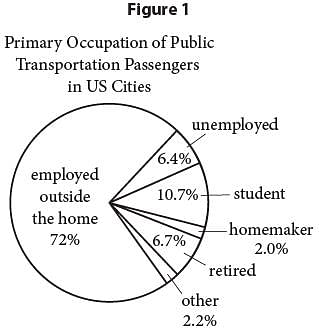

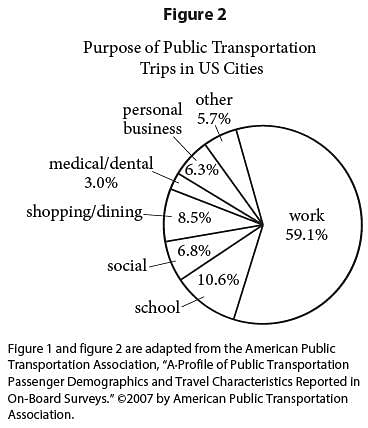

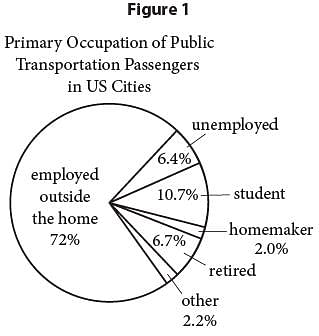

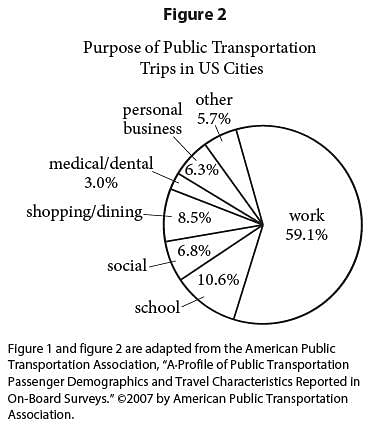

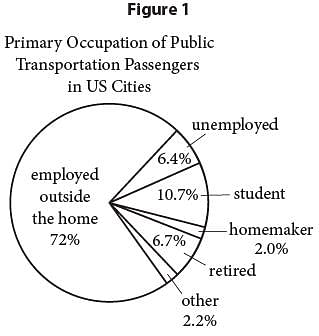

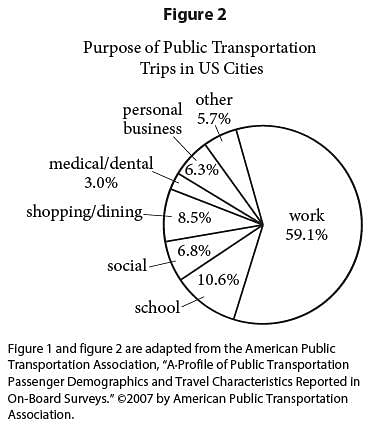

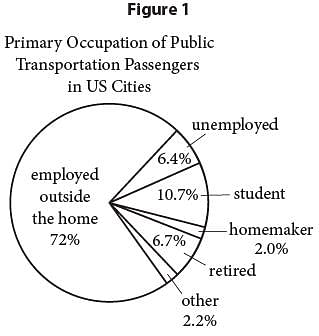

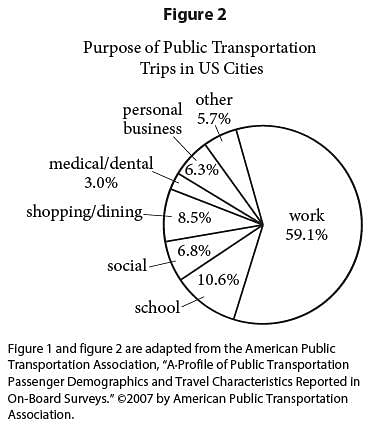

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Taras Grescoe, Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile. ©2012 by Taras Grescoe.

Though there are 600 million cars on the planet,

and counting, there are also seven billion people,

which means that for the vast majority of us getting

around involves taking buses, ferryboats, commuter

(5) trains, streetcars, and subways. In other words,

traveling to work, school, or the market means being

a straphanger: somebody who, by choice or necessity,

relies on public transport, rather than a privately

owned automobile.

(10) Half the population of New York, Toronto, and

London do not own cars. Public transport is how

most of the people of Asia and Africa, the world’s

most populous continents, travel. Every day, subway

systems carry 155 million passengers, thirty-four

(15) times the number carried by all the world’s airplanes,

and the global public transport market is now valued

at $428 billion annually. A century and a half after

the invention of the internal combustion engine,

private car ownership is still an anomaly.

(20) And yet public transportation, in many minds, is

the opposite of glamour—a squalid last resort for

those with one too many impaired driving charges,

too poor to afford insurance, or too decrepit to get

behind the wheel of a car. In much of North

(25) America, they are right: taking transit is a depressing

experience. Anybody who has waited far too long on

a street corner for the privilege of boarding a

lurching, overcrowded bus, or wrestled luggage onto

subways and shuttles to get to a big city airport,

(30) knows that transit on this continent tends to be

underfunded, ill-maintained, and ill-planned. Given

the opportunity, who wouldn’t drive? Hopping in a

car almost always gets you to your destination more

quickly.

(35) It doesn’t have to be like this. Done right, public

transport can be faster, more comfortable, and

cheaper than the private automobile. In Shanghai,

German-made magnetic levitation trains skim over

elevated tracks at 266 miles an hour, whisking people

(40) to the airport at a third of the speed of sound. In

provincial French towns, electric-powered streetcars

run silently on rubber tires, sliding through narrow

streets along a single guide rail set into cobblestones.

From Spain to Sweden, Wi-Fi equipped high-speed

(45) trains seamlessly connect with highly ramified metro

networks, allowing commuters to work on laptops as

they prepare for same-day meetings in once distant

capital cities. In Latin America, China, and India,

working people board fast-loading buses that move

(50) like subway trains along dedicated busways, leaving

the sedans and SUVs of the rich mired in

dawn-to-dusk traffic jams. And some cities have

transformed their streets into cycle-path freeways,

making giant strides in public health and safety and

(55) the sheer livability of their neighborhoods—in the

process turning the workaday bicycle into a viable

form of mass transit.

If you credit the demographers, this transit trend

has legs. The “Millenials,” who reached adulthood

(60) around the turn of the century and now outnumber

baby boomers, tend to favor cities over suburbs, and

are far more willing than their parents to ride buses

and subways. Part of the reason is their ease with

iPads, MP3 players, Kindles, and smartphones: you

(65) can get some serious texting done when you’re not

driving, and earbuds offer effective insulation from

all but the most extreme commuting annoyances.

Even though there are more teenagers in the country

than ever, only ten million have a driver’s license

(70) (versus twelve million a generation ago). Baby

boomers may have been raised in Leave It to Beaver

suburbs, but as they retire, a significant contingent is

favoring older cities and compact towns where they

have the option of walking and riding bikes. Seniors,

(75) too, are more likely to use transit, and by 2025, there

will be 64 million Americans over the age of

sixty-five. Already, dwellings in older neighborhoods

in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Denver, especially

those near light-rail or subway stations, are

(80) commanding enormous price premiums over

suburban homes. The experience of European and

Asian cities shows that if you make buses, subways,

and trains convenient, comfortable, fast, and safe, a

surprisingly large percentage of citizens will opt to

(85) ride rather than drive.

Q. What function does the third paragraph (lines 20-34) serve in the passage as a whole?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Taras Grescoe, Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile. ©2012 by Taras Grescoe.

Though there are 600 million cars on the planet,

and counting, there are also seven billion people,

which means that for the vast majority of us getting

around involves taking buses, ferryboats, commuter

(5) trains, streetcars, and subways. In other words,

traveling to work, school, or the market means being

a straphanger: somebody who, by choice or necessity,

relies on public transport, rather than a privately

owned automobile.

(10) Half the population of New York, Toronto, and

London do not own cars. Public transport is how

most of the people of Asia and Africa, the world’s

most populous continents, travel. Every day, subway

systems carry 155 million passengers, thirty-four

(15) times the number carried by all the world’s airplanes,

and the global public transport market is now valued

at $428 billion annually. A century and a half after

the invention of the internal combustion engine,

private car ownership is still an anomaly.

(20) And yet public transportation, in many minds, is

the opposite of glamour—a squalid last resort for

those with one too many impaired driving charges,

too poor to afford insurance, or too decrepit to get

behind the wheel of a car. In much of North

(25) America, they are right: taking transit is a depressing

experience. Anybody who has waited far too long on

a street corner for the privilege of boarding a

lurching, overcrowded bus, or wrestled luggage onto

subways and shuttles to get to a big city airport,

(30) knows that transit on this continent tends to be

underfunded, ill-maintained, and ill-planned. Given

the opportunity, who wouldn’t drive? Hopping in a

car almost always gets you to your destination more

quickly.

(35) It doesn’t have to be like this. Done right, public

transport can be faster, more comfortable, and

cheaper than the private automobile. In Shanghai,

German-made magnetic levitation trains skim over

elevated tracks at 266 miles an hour, whisking people

(40) to the airport at a third of the speed of sound. In

provincial French towns, electric-powered streetcars

run silently on rubber tires, sliding through narrow

streets along a single guide rail set into cobblestones.

From Spain to Sweden, Wi-Fi equipped high-speed

(45) trains seamlessly connect with highly ramified metro

networks, allowing commuters to work on laptops as

they prepare for same-day meetings in once distant

capital cities. In Latin America, China, and India,

working people board fast-loading buses that move

(50) like subway trains along dedicated busways, leaving

the sedans and SUVs of the rich mired in

dawn-to-dusk traffic jams. And some cities have

transformed their streets into cycle-path freeways,

making giant strides in public health and safety and

(55) the sheer livability of their neighborhoods—in the

process turning the workaday bicycle into a viable

form of mass transit.

If you credit the demographers, this transit trend

has legs. The “Millenials,” who reached adulthood

(60) around the turn of the century and now outnumber

baby boomers, tend to favor cities over suburbs, and

are far more willing than their parents to ride buses

and subways. Part of the reason is their ease with

iPads, MP3 players, Kindles, and smartphones: you

(65) can get some serious texting done when you’re not

driving, and earbuds offer effective insulation from

all but the most extreme commuting annoyances.

Even though there are more teenagers in the country

than ever, only ten million have a driver’s license

(70) (versus twelve million a generation ago). Baby

boomers may have been raised in Leave It to Beaver

suburbs, but as they retire, a significant contingent is

favoring older cities and compact towns where they

have the option of walking and riding bikes. Seniors,

(75) too, are more likely to use transit, and by 2025, there

will be 64 million Americans over the age of

sixty-five. Already, dwellings in older neighborhoods

in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Denver, especially

those near light-rail or subway stations, are

(80) commanding enormous price premiums over

suburban homes. The experience of European and

Asian cities shows that if you make buses, subways,

and trains convenient, comfortable, fast, and safe, a

surprisingly large percentage of citizens will opt to

(85) ride rather than drive.

Q. Which choice does the author explicitly cite as an advantage of automobile travel in North America?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Taras Grescoe, Straphanger: Saving Our Cities and Ourselves from the Automobile. ©2012 by Taras Grescoe.

Though there are 600 million cars on the planet,

and counting, there are also seven billion people,

which means that for the vast majority of us getting

around involves taking buses, ferryboats, commuter

(5) trains, streetcars, and subways. In other words,

traveling to work, school, or the market means being

a straphanger: somebody who, by choice or necessity,

relies on public transport, rather than a privately

owned automobile.

(10) Half the population of New York, Toronto, and

London do not own cars. Public transport is how

most of the people of Asia and Africa, the world’s

most populous continents, travel. Every day, subway

systems carry 155 million passengers, thirty-four

(15) times the number carried by all the world’s airplanes,

and the global public transport market is now valued

at $428 billion annually. A century and a half after

the invention of the internal combustion engine,

private car ownership is still an anomaly.

(20) And yet public transportation, in many minds, is

the opposite of glamour—a squalid last resort for

those with one too many impaired driving charges,

too poor to afford insurance, or too decrepit to get

behind the wheel of a car. In much of North

(25) America, they are right: taking transit is a depressing

experience. Anybody who has waited far too long on

a street corner for the privilege of boarding a

lurching, overcrowded bus, or wrestled luggage onto

subways and shuttles to get to a big city airport,

(30) knows that transit on this continent tends to be

underfunded, ill-maintained, and ill-planned. Given

the opportunity, who wouldn’t drive? Hopping in a

car almost always gets you to your destination more

quickly.

(35) It doesn’t have to be like this. Done right, public

transport can be faster, more comfortable, and