CAT Mock Test - 19 (November 21) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test - 19 (November 21)

Direction: Read the passage carefully and answer the questions.

The recurring theme of equality in the United States has flared into a fervent moral issue at crucial stages: the Revolutionary and Jacksonian periods, the Civil War, the populist and progressive eras, the New Deal, and the 1960s and 1980s. The legitimacy of American society is challenged by some set of people unhappy with the degree of equality. New claims are laid, new understandings are reached, and new policies for political or economic equality are instituted. Yet the equality issue endures outside these moments of fervor. Ideologies in favor of extending equality are arrayed against others that would limit its scope; advocates of social justice confront defenders of liberty.

In the moments of egalitarian ascendancy, libertarians are on the defensive. In the moments of retrenchment, egalitarians cling to previous gains. And in either period the enemy is likely to be the "special interests " that have too much power. In egalitarian times, these are the moneyed interests. In times of retrenchment, these are labor or big government and its beneficiaries.

The moments of creedal passion, in Samuel Huntington's words, have usually been outbursts of egalitarianism. In part, the passion springs from the self—interest of those who would benefit from a more equal distribution of goods or political influence. But the passion also springs from ideology and values, including deep religious justifications for equality.

The passion accompanying the discovery or rediscovery that ideals do not match reality is particularly intense when the ideal is as deeply felt as is equality. Yet there can be passion on the nonegalitarian side as well. The self—interested passion to protect an established position may be even more powerful than the passion to redress inequality, though its expression may be more muted.

Devotion to inequality may also be based on ideals, such as liberty, individualism, and the free market, which are no less ancient and venerable. Like the ideals of equality, these alternative ideals serve as yardsticks for measuring whether society has moved away from its true principles.

Yet the spirit of reform during Reconstruction dissipated in the face of spent political struggles, sluggish social institutions, and outright mendacity. Society's entrepreneurial energy was channeled into economic activity, and the courts failed to endorse many of the reformers' grandest visions. The egalitarian thrust of the Populists around the turn of the century inspired an anti—egalitarian counterthrust over the next two decades.

Americans do not have an ideology that assigns clear priority to one value over any other. At every historical juncture where equality was an issue, its proponents failed to do all that they had set out to do. Swings in the equality of social conditions are restrained not just by institutional obstacles but by fundamental conflicts of values that are a traditional element of American politics. Faith in the individualistic work ethic and belief in the legitimacy of unequal wealth retard progression to the egalitarian left. As for conservatism, the indelible tenet of political equality firmly restrains the right and confirms a commitment to the disadvantaged. In seeking equal opportunity over equal result, Americans forego a ceiling, not a floor.

Q. According to the passage, none of the following statements are true EXCEPT:

Direction: Read the passage carefully and answer the questions

The last ice age has left its telltales written quite clearly across the landscape. When Louis Agassiz first promulgated his theory that ice had once covered the Swiss countryside, he looked to the valleys there that retain glaciers to this day. Like other observers, he noted the presence of strange boulders, called "erratics, " tossed down in valleys like flotsam after a flood had drained away. He saw the strange polish along the bedrock—a sheen imparted as if by some massive swipe of sandpaper; he saw the debris of rocks and boulders fringing the margin of existing glaciers. He saw what can be seen still, markings in stone that indicated that ice once flowed over vast stretches of land now clear and verdant.

The first great glaciations must have scored the earth as deeply in their turn, and, in principle, we ought to be able to track the history of the early ice ages by following the same reasoning Agassiz used to persuade himself and his contemporaries that ice once covered the earth. But the marks left by these earlier glaciations are quite subtle, tracks turned ghostly with great age. There are, however, telltale deposits of ancient rocks that strongly suggest that they had been ground together and laid down by the spread of ice.

The Australian climate historian L.A. Frakes has prospected through various theories proposed to account for those early ice ages. He isn't terribly enthusiastic about any of the possible culprits, but his choice for the least unlikely of them all emerges out of the recent revival of what was once a radically unorthodox idea: that continents drift over the face of the planet. Frakes argues that the glaciers originated at sites near the poles and that the ice ages began because the continents of the early earth had drifted to positions that took more and more of their land nearer to the polar regions.

More land near the poles meant that more precipitation fell as snow and could be compacted on land to form glaciers. With enough glaciers, the increase in the amount of sunlight reflected back into space off the glistening white sheen of the ice effectively reduced the amount by which the sun warmed the earth, creating the feedback loop by which the growth of glaciers encouraged the growth of more glaciers. Rocks have been found in North America, Africa and Australia whose ages appear to hover around the 2.3 billion—year—old mark. That date and their spread are vague enough, however, to make it almost impossible to determine just how much of the earth was icebound during the possible range of time in which each of the glacial deposits was formed.

Uncertainties about both the timing and the extent of these glaciers also muddy the search for the cause of the ancient ice ages. The record is so spotty that geologists are not sure whether areas near the equator or nearer the poles were the coolest places on earth. It's also possible that volcanic eruptions had tossed enough dust into the atmosphere to screen out sunlight and cool the earth. While some of the glacial records in the rocks do indeed contain evidence of volcanic activity prior to the buildup of glacial debris, others do not.

Such traces are the currency of science—data—and like money, a richness of data both buys you some credibility and ties you down, eliminating at least some theoretically plausible explanations. For this early period, theorists have come up with a variety of ideas to explain the ancient ice ages, all elegant and mostly immune to both proof and criticism. For example, a change in the earth's orbit could have reduced the amount of sunlight reaching the planet. However, the only physical signature of such an event that would show in the rocks would be the marks of the glaciers themselves.

Q. Suppose that an advocate of the "change in orbit " theory of the ancient ice ages criticizes a defender of the "volcanic eruption " theory on the grounds that only some of the glacial records contain evidence of prior volcanic activity. The defender might justifiably counter this attack by pointing out that:

| 1 Crore+ students have signed up on EduRev. Have you? Download the App |

Direction: Read the passage carefully and answer the questions

The last ice age has left its telltales written quite clearly across the landscape. When Louis Agassiz first promulgated his theory that ice had once covered the Swiss countryside, he looked to the valleys there that retain glaciers to this day. Like other observers, he noted the presence of strange boulders, called "erratics, " tossed down in valleys like flotsam after a flood had drained away. He saw the strange polish along the bedrock—a sheen imparted as if by some massive swipe of sandpaper; he saw the debris of rocks and boulders fringing the margin of existing glaciers. He saw what can be seen still, markings in stone that indicated that ice once flowed over vast stretches of land now clear and verdant.

The first great glaciations must have scored the earth as deeply in their turn, and, in principle, we ought to be able to track the history of the early ice ages by following the same reasoning Agassiz used to persuade himself and his contemporaries that ice once covered the earth. But the marks left by these earlier glaciations are quite subtle, tracks turned ghostly with great age. There are, however, telltale deposits of ancient rocks that strongly suggest that they had been ground together and laid down by the spread of ice.

The Australian climate historian L.A. Frakes has prospected through various theories proposed to account for those early ice ages. He isn't terribly enthusiastic about any of the possible culprits, but his choice for the least unlikely of them all emerges out of the recent revival of what was once a radically unorthodox idea: that continents drift over the face of the planet. Frakes argues that the glaciers originated at sites near the poles and that the ice ages began because the continents of the early earth had drifted to positions that took more and more of their land nearer to the polar regions.

More land near the poles meant that more precipitation fell as snow and could be compacted on land to form glaciers. With enough glaciers, the increase in the amount of sunlight reflected back into space off the glistening white sheen of the ice effectively reduced the amount by which the sun warmed the earth, creating the feedback loop by which the growth of glaciers encouraged the growth of more glaciers. Rocks have been found in North America, Africa and Australia whose ages appear to hover around the 2.3 billion—year—old mark. That date and their spread are vague enough, however, to make it almost impossible to determine just how much of the earth was icebound during the possible range of time in which each of the glacial deposits was formed.

Uncertainties about both the timing and the extent of these glaciers also muddy the search for the cause of the ancient ice ages. The record is so spotty that geologists are not sure whether areas near the equator or nearer the poles were the coolest places on earth. It's also possible that volcanic eruptions had tossed enough dust into the atmosphere to screen out sunlight and cool the earth. While some of the glacial records in the rocks do indeed contain evidence of volcanic activity prior to the buildup of glacial debris, others do not.

Such traces are the currency of science—data—and like money, a richness of data both buys you some credibility and ties you down, eliminating at least some theoretically plausible explanations. For this early period, theorists have come up with a variety of ideas to explain the ancient ice ages, all elegant and mostly immune to both proof and criticism. For example, a change in the earth's orbit could have reduced the amount of sunlight reaching the planet. However, the only physical signature of such an event that would show in the rocks would be the marks of the glaciers themselves.

Q. According to the passage, which of the following is most likely to be true about the relationship between the amount of data one has about a phenomenon and the number of theoretically plausible explanations?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

The opposition between 'nature' and 'culture' is problematic for many reasons, but there's one that we rarely discuss. The 'nature vs culture' dualism leaves out an entire domain that properly belongs to neither: the world of waste. The mountains of waste that we produce every year or the new cosmos of micro-plastics expanding through our oceans – none of these have ever been entered into the ledger under 'culture'. Waste is precisely what dissolves the distinction between nature and culture. Nature and waste have fused at both planetary and microbiological scales. Similarly, waste is not merely a by-product of culture: it is culture. To focus our gaze on waste is not an act of morbid negativity; it is an act of cultural realism. If we look at the material ages of human history, from the Stone Age and the Bronze Age through to the Steam Age and the Information Age, we get the illusory sense that hard things are dematerialising. In fact, the opposite is true. The Steam Age launched a great explosion of material goods that has mushroomed exponentially ever since, while statistics about our current rates of waste numb the mind.

To say that we live in a Waste Age is to acknowledge both its geological and economic dimensions. It is to acknowledge that growth is entirely dependent on the relentless and ruthlessly efficient generation of waste. Is this an ungenerous and pessimistic take on human activity in the 21st century? On the contrary. Invoking the Waste Age offers the opportunity for a radical shift in late-capitalist civilisation. By recognising the scale of the crisis can we reorient society and the economy towards less polluting modes of producing, consuming and living.

The problem is that waste has always been a marginal issue, both literally and figuratively. It has been dumped in and on the peripheries, consigned to that mythical place called 'away'. It has always been an 'externality', an unavoidable byproduct of necessary industrialisation. But it is now an internality – internal to every ecosystem and every digestive system from marine micro-organisms to humans. To invoke the Waste Age is to usher in the hope of a cleaner future.

Contrary to what we might assume, wastefulness is not a natural human instinct – we had to be taught how to do it. Consumers had to be persuaded that this magical new substance – plastic – was not too good to be thrown away. Some observers were quick to disapprove. Vance Packard's details at length the different forms of planned obsolescence, from products engineered to fail to those that are simply meant to be more desirable than last year's model. It is understood that such obsolescence is a necessary feature of a healthy economy – from politicians to cynical businessmen to consumers who think it is their patriotic duty to shop and support the economy. The very idea of the 'lifetime guarantee' conjured up the spectre of unemployment and shuttered factories. You might think that I'm suggesting that recycling is the answer to this crisis. Recycling rates are pathetically inadequate, and in many countries the system is essentially broken. The notion of recycling works to justify the production of more virgin plastics and other materials, as if it's alright because they will be recycled.

Q. The author of this passage is LEAST likely to agree with which of the following:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the given question.

The opposition between 'nature' and 'culture' is problematic for many reasons, but there's one that we rarely discuss. The 'nature vs culture' dualism leaves out an entire domain that properly belongs to neither: the world of waste. The mountains of waste that we produce every year or the new cosmos of micro-plastics expanding through our oceans – none of these have ever been entered into the ledger under 'culture'. Waste is precisely what dissolves the distinction between nature and culture. Nature and waste have fused at both planetary and microbiological scales. Similarly, waste is not merely a by-product of culture: it is culture. To focus our gaze on waste is not an act of morbid negativity; it is an act of cultural realism. If we look at the material ages of human history, from the Stone Age and the Bronze Age through to the Steam Age and the Information Age, we get the illusory sense that hard things are dematerialising. In fact, the opposite is true. The Steam Age launched a great explosion of material goods that has mushroomed exponentially ever since, while statistics about our current rates of waste numb the mind.

To say that we live in a Waste Age is to acknowledge both its geological and economic dimensions. It is to acknowledge that growth is entirely dependent on the relentless and ruthlessly efficient generation of waste. Is this an ungenerous and pessimistic take on human activity in the 21st century? On the contrary. Invoking the Waste Age offers the opportunity for a radical shift in late-capitalist civilisation. By recognising the scale of the crisis can we reorient society and the economy towards less polluting modes of producing, consuming and living.

The problem is that waste has always been a marginal issue, both literally and figuratively. It has been dumped in and on the peripheries, consigned to that mythical place called 'away'. It has always been an 'externality', an unavoidable byproduct of necessary industrialisation. But it is now an internality – internal to every ecosystem and every digestive system from marine micro-organisms to humans. To invoke the Waste Age is to usher in the hope of a cleaner future.

Contrary to what we might assume, wastefulness is not a natural human instinct – we had to be taught how to do it. Consumers had to be persuaded that this magical new substance – plastic – was not too good to be thrown away. Some observers were quick to disapprove. Vance Packard's details at length the different forms of planned obsolescence, from products engineered to fail to those that are simply meant to be more desirable than last year's model. It is understood that such obsolescence is a necessary feature of a healthy economy – from politicians to cynical businessmen to consumers who think it is their patriotic duty to shop and support the economy. The very idea of the 'lifetime guarantee' conjured up the spectre of unemployment and shuttered factories. You might think that I'm suggesting that recycling is the answer to this crisis. Recycling rates are pathetically inadequate, and in many countries the system is essentially broken. The notion of recycling works to justify the production of more virgin plastics and other materials, as if it's alright because they will be recycled.

Q. The author of the passage is LEAST likely to agree with which of the following statements?

Directions: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3 and 4) given in this question, when properly sequenced, form a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper order for the sentences and key in this sequence of four numbers as your answer.

1. Work stress poses risk to the physical health of the employee and consequently influences the health of the organisation.

2. No professional is untouched by stress, starting from a surgeon to an artist or a sales executive to a commercial pilot.

3. Job stress, in the early stages, can 'rev up' the body and improve performance in the workplace.

4. Although, the performance will eventually decline as the person's health will deteriorate.

Five jumbled-up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer.

1. The Renaissance was an era of profound cultural rejuvenation rooted in classical antiquity.

2. It marked an age where scientific inquiry was championed alongside artistic creativity.

3. Great thinkers during the period were often persecuted, facing charges of heresy.

4. Notably, this period saw the genesis of masterpiece paintings that remain invaluable today.

5. Conversely, the Dark Ages were marked by widespread illiteracy and the stagnation of cultural progress.

Five jumbled-up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer.

1. Deep-sea exploration has unveiled bizarre, alien-like creatures previously unknown to science.

2. These expeditions demand highly advanced technology to survive the ocean's crushing depths.

3. Discoveries made in these realms are often used in developing new materials and medical innovations.

4. The Mariana Trench, the deepest known point, extends nearly 11 kilometers down, farther than Mount Everest is tall.

5. Space travel requires complex calculations to overcome Earth's gravity.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Sustaining a social movement is difficult, especially if its constituents come from socioeconomically disenfranchised backgrounds and are cynical about their chances of success. Attending marches and protests could be costly. The prospects of being imprisoned or persecuted are daunting. Against these obstacles, anger rallies people together - it transforms public, societal causes into intimate, personal reasons that you care about and are devoted to. By providing the individual with the instinctive justification to keep believing and carrying on, anger spurs and sustains action, even if the odds of succeeding are slim.

Directions: The passage given below is followed by four alternative summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Together with Martha Nussbaum, Sen formulated an alternative for understanding wellbeing: the capability approach, which stipulates that both personal characteristics and social circumstances affect what people can achieve with a given amount of resources. Giving books to a person who cannot read does not increase their wellbeing, just as providing them with a car does not increase mobility if there are no decent roads. According to Sen, what the person manages to do or to be - such as being well-nourished or being able to appear in public without shame - are what really matter for wellbeing. Sen calls these achievements the functionings of the person. However, he further claims that defining wellbeing only in terms of functioning is insufficient, because wellbeing also includes freedom. Sen suggests that wellbeing should be understood in terms of people's real opportunities - that is, all possible combinations of functionings from which they can choose.

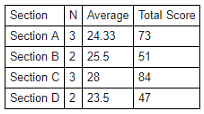

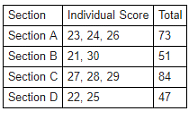

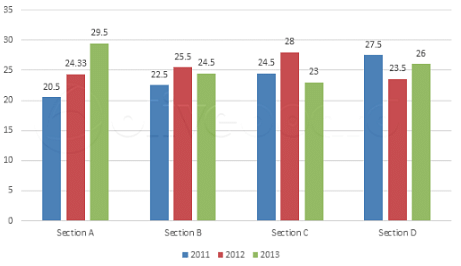

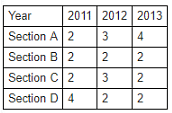

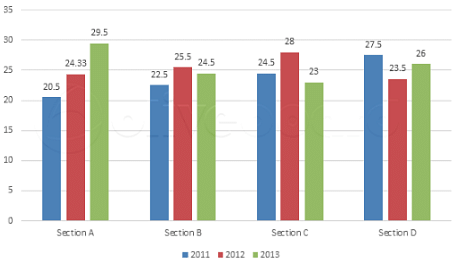

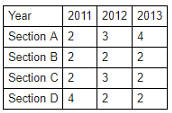

Directions: In a school, for class 10th the sections are allotted on the basis of the scores of the student in class 9th. There are four sections in class 9th namely A, B, C, D. A student obtaining highest marks will be allotted section P in class 10th. On the similar basis sections Q, R, S are allotted. P is the best section, Q, R and S are the 2nd, 3rd and 4th best section respectively.

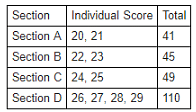

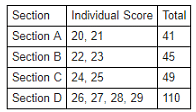

A record of score of 10 students were kept.

Each year the lowest and highest score increases by 1.

Each student got distinct marks as per record of January, 2011, the minimum marks is 20 and the maximum marks is 29. The sections were to be continued for 1 year in class 10th. Different sets of number of students are there in class 9th for any two year. In class 10th, section P has 4 students and, Q, R, S have 2 students each.

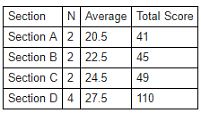

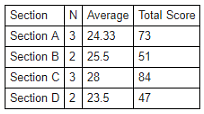

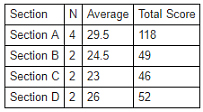

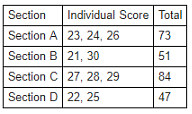

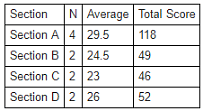

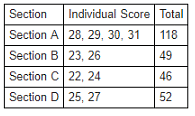

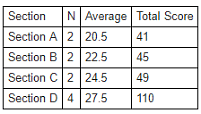

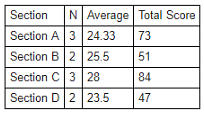

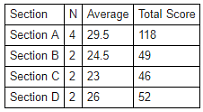

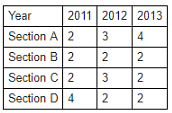

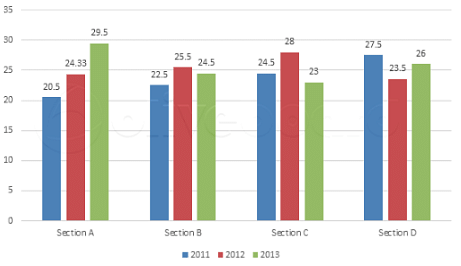

The below table gives the number of students in each section of class 9th over the years:

Q. What was the highest marks obtained by the student of section B in the year 2013?

Directions: In a school, for class 10th the sections are allotted on the basis of the scores of the student in class 9th. There are four sections in class 9th namely A, B, C, D. A student obtaining highest marks will be allotted section P in class 10th. On the similar basis sections Q, R, S are allotted. P is the best section, Q, R and S are the 2nd, 3rd and 4th best section respectively.

A record of score of 10 students were kept.

Each year the lowest and highest score increases by 1.

Each student got distinct marks as per record of January, 2011, the minimum marks is 20 and the maximum marks is 29. The sections were to be continued for 1 year in class 10th. Different sets of number of students are there in class 9th for any two year. In class 10th, section P has 4 students and, Q, R, S have 2 students each.

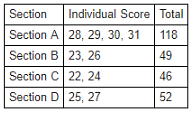

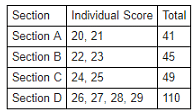

The below table gives the number of students in each section of class 9th over the years:

Q. Total number of students from section C moved in section Q in the year 2011 is what was the highest marks obtained by the student of section B in the year 2013?

Directions: In a school, for class 10th the sections are allotted on the basis of the scores of the student in class 9th. There are four sections in class 9th namely A, B, C, D. A student obtaining highest marks will be allotted section P in class 10th. On the similar basis sections Q, R, S are allotted. P is the best section, Q, R and S are the 2nd, 3rd and 4th best section respectively.

A record of score of 10 students were kept.

Each year the lowest and highest score increases by 1.

Each student got distinct marks as per record of January, 2011, the minimum marks is 20 and the maximum marks is 29. The sections were to be continued for 1 year in class 10th. Different sets of number of students are there in class 9th for any two year. In class 10th, section P has 4 students and, Q, R, S have 2 students each.

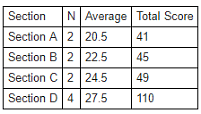

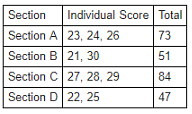

The below table gives the number of students in each section of class 9th over the years:

Q. Students of how many sections showed a consistent increase in marks obtained?

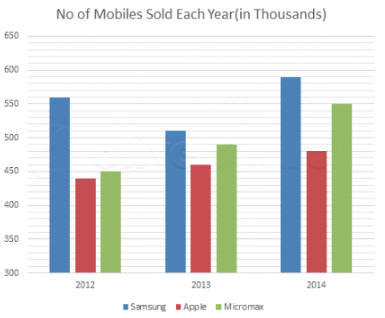

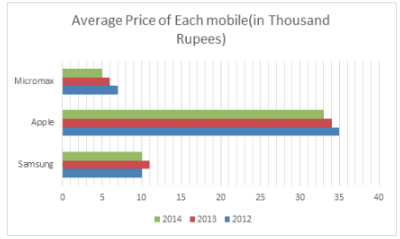

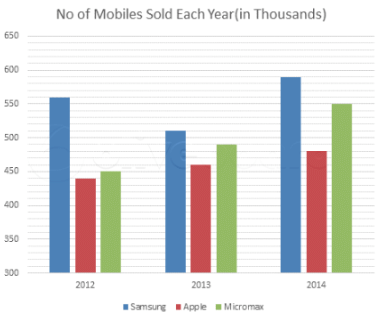

Directions: The first bar graph shows no of mobile phones sold each year by 3 companies for 2012, 2013 & 2014. The 2nd graph shows the variation of avg. price per mobile for the three consecutive years.

Q. What percent of the total money generated by selling mobile phones came from Apple in 2014?

Directions: The first bar graph shows no of mobile phones sold each year by 3 companies for 2012, 2013 & 2014. The 2nd graph shows the variation of avg. price per mobile for the three consecutive years.

Q. What is the % change in the avg. price of mobile phones in the year 2013 compared to the year 2012?

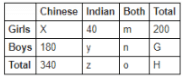

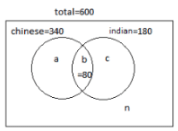

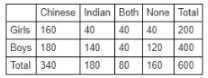

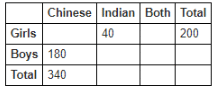

Directions : Nalanda University has 600 students. A survey was conducted to know how many of them like Indian dishes and how many of them like Chinese food. The following additional information is known:-

a. Girls who like Indian dishes they like Chinese dishes also.

b. 35% of boys like Indian dishes.

c. Total number of boys who like both dishes are same as total number of girls who like both dishes.

Q. Total number of girls who like Chinese.

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question the follows:

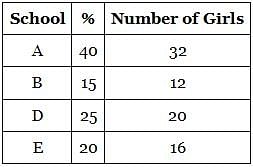

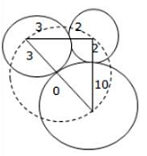

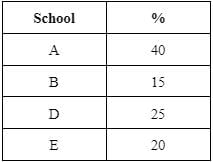

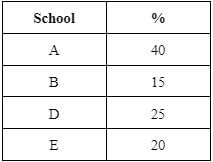

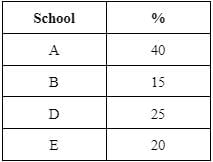

A business strategy competition was conducted in which 5 schools A, B, C, D and E participated in the final round. The event was finally won by school C. The following table gives the number of girls from A, B, D and E who participated in the event as a percentage of the total students from school C who participated in the event.

It is also known that the ratio of the number of girls to boys in the schools A, B, D and E who participated in the event was 1:3, 3:2, 4:3 and 5:3 in no particular order.

Q. If it is known that 80 students participated from school C, find the difference between the number of boys who participated from school B and school D?

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question the follows:

A business strategy competition was conducted in which 5 schools A, B, C, D and E participated in the final round. The event was finally won by school C. The following table gives the number of girls from A, B, D and E who participated in the event as a percentage of the total students from school C who participated in the event.

It is also known that the ratio of the number of girls to boys in the schools A, B, D and E who participated in the event was 1:3, 3:2, 4:3 and 5:3 in no particular order.

Q. It is known that the number of boys who participated from schools A,B,D and E were 14, 24,27 and 30 in no particular order. Find the maximum number of students who participated from the four schools put together?

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question the follows:

A business strategy competition was conducted in which 5 schools A, B, C, D and E participated in the final round. The event was finally won by school C. The following table gives the number of girls from A, B, D and E who participated in the event as a percentage of the total students from school C who participated in the event.

It is also known that the ratio of the number of girls to boys in the schools A, B, D and E who participated in the event was 1:3, 3:2, 4:3 and 5:3 in no particular order.

Q. It is known that 80 students participated from school C. Which among the following can be the ratio of the number of boys who participated from school A to the total number of students who participated from school B?

The profit percentage earned by selling an item for Rs. 1078 is equal to the percentage loss incurred by selling the same item for Rs. 882. What should be the Marked Price of the item if it is to be sold at approximately 15% profit, after giving 10% discount to the customer?

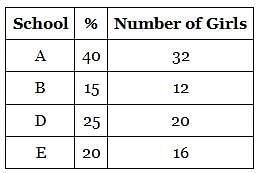

What is the volume of a hollow box made from 21 x 28 cm rectangular cardboard by cutting 7 x 7 cm squares from the four corners and folding the piece along the cuts?

Gagan and Laxman started a business investing Rs. 64000 and Rs. 40000 respectively. After three months Sujit joined them investing Rs. 82000. 3 months after starting business Gagan and Laxman withdraw Rs. 15000 and Rs. 18000 respectively. At the end of the year find the sum of shares of Sujit and Laxman in total profit of Rs. 6450

log x(1 + 8-1 + 8-2 + 8-3 + .... ∞) > log x(1 + 6-1 + 6-2 + 6-3 + .... ∞), then logx6921 - logx1296 will be

If the selling price of the article is reduced by 40% and the cost price remains the same, the profit reduces by 50%. Find the original profit % of the article?

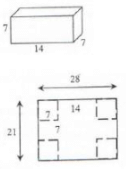

Find the area of the circle passing through centers of three circles with radius 2 m, 3 m and 10 m placed in such a way that each circle touches the other two circles externally.

An escalator moves at a constant rate from one floor up to the next floor. Jack walks up 29 steps while traveling on the escalator between the floors. Jill takes twice as long to travel between the floors and walks up only 11 steps. When it is stopped, how many steps does the escalator has between the two floors?

A person can complete a job in 120 days. He works alone on Day 1. On Day 2, he is joined by another person who also can complete the job in exactly 120 days. On Day 3, they are joined by another person of equal efficiency. Like this, everyday a new person with the same efficiency joins the work. How many days are required to complete the job?

If n! has 4 zeros at the end and (n+1)! has six zeros at the end, then n can be:

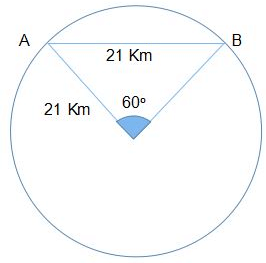

Hyderabad ring road is in the form of a perfect circle of diameter 42 km. 2 points A and B lie on the ring road. There is another expressway that connects point A directly to point B. The length of the expressway that connects A and B is the same as the radius of the ring road. A person starts from point A and travels to point B through the ring road by taking the shortest route and immediately returns to A from B through the expressway. If the person completes the journey in half an hour, what is his speed (in kmph)?

What is the highest value of x in the expression (167!)/ (24!)x to an yield integral answer?