CAT Mini Mock Test - 6 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mini Mock Test - 6

Creativity is at once our most precious resource and our most inexhaustible one. As anyone who has ever spent any time with children knows, every single human being is born creative; every human being is innately endowed with the ability to combine and recombine data, perceptions, materials and ideas, and devise new ways of thinking and doing. What fosters creativity? More than anything else: the presence of other creative people. The big myth is that creativity is the province of great individual geniuses. In fact creativity is a social process. Our biggest creative breakthroughs come when people learn from, compete with, and collaborate with other people.

Cities are the true fonts of creativity... With their diverse populations, dense social networks, and public spaces where people can meet spontaneously and serendipitously, they spark and catalyze new ideas. With their infrastructure for finance, organization and trade, they allow those ideas to be swiftly actualized.

As for what staunches creativity, that's easy, if ironic. It's the very institutions that we build to manage, exploit and perpetuate the fruits of creativity — our big bureaucracies, and sad to say, too many of our schools. Creativity is disruptive; schools and organizations are regimented, standardized and stultifying.

The education expert Sir Ken Robinson points to a 1968 study reporting on a group of 1,600 children who were tested over time for their ability to think in out-of-the-box ways. When the children were between 3 and 5 years old, 98 percent achieved positive scores. When they were 8 to 10, only 32 percent passed the same test, and only 10 percent at 13 to 15. When 280,000 25-year-olds took the test, just 2 percent passed. By the time we are adults, our creativity has been wrung out of us.

I once asked the great urbanist Jane Jacobs what makes some places more creative than others. She said, essentially, that the question was an easy one. All cities, she said, were filled with creative people; that's our default state as people. But some cities had more than their shares of leaders, people and institutions that blocked out that creativity. She called them "squelchers."

Creativity (or the lack of it) follows the same general contours of the great socio-economic divide - our rising inequality - that plagues us. According to my own estimates, roughly a third of us across the United States, and perhaps as much as half of us in our most creative cities - are able to do work which engages our creative faculties to some extent, whether as artists, musicians, writers, techies, innovators, entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, journalists or educators - those of us who work with our minds. That leaves a group that I term "the other 66 percent," who toil in low-wage rote and rotten jobs — if they have jobs at all — in which their creativity is subjugated, ignored or wasted.

Creativity itself is not in danger. It's flourishing is all around us - in science and technology, arts and culture, in our rapidly revitalizing cities. But we still have a long way to go if we want to build a truly creative society that supports and rewards the creativity of each and every one of us.

Q.

In the author's view, cities promote human creativity for all the following reasons EXCEPT that they

Creativity is at once our most precious resource and our most inexhaustible one. As anyone who has ever spent any time with children knows, every single human being is born creative; every human being is innately endowed with the ability to combine and recombine data, perceptions, materials and ideas, and devise new ways of thinking and doing. What fosters creativity? More than anything else: the presence of other creative people. The big myth is that creativity is the province of great individual geniuses. In fact creativity is a social process. Our biggest creative breakthroughs come when people learn from, compete with, and collaborate with other people.

Cities are the true fonts of creativity... With their diverse populations, dense social networks, and public spaces where people can meet spontaneously and serendipitously, they spark and catalyze new ideas. With their infrastructure for finance, organization and trade, they allow those ideas to be swiftly actualized.

As for what staunches creativity, that's easy, if ironic. It's the very institutions that we build to manage, exploit and perpetuate the fruits of creativity — our big bureaucracies, and sad to say, too many of our schools. Creativity is disruptive; schools and organizations are regimented, standardized and stultifying.

The education expert Sir Ken Robinson points to a 1968 study reporting on a group of 1,600 children who were tested over time for their ability to think in out-of-the-box ways. When the children were between 3 and 5 years old, 98 percent achieved positive scores. When they were 8 to 10, only 32 percent passed the same test, and only 10 percent at 13 to 15. When 280,000 25-year-olds took the test, just 2 percent passed. By the time we are adults, our creativity has been wrung out of us.

I once asked the great urbanist Jane Jacobs what makes some places more creative than others. She said, essentially, that the question was an easy one. All cities, she said, were filled with creative people; that's our default state as people. But some cities had more than their shares of leaders, people and institutions that blocked out that creativity. She called them "squelchers."

Creativity (or the lack of it) follows the same general contours of the great socio-economic divide - our rising inequality - that plagues us. According to my own estimates, roughly a third of us across the United States, and perhaps as much as half of us in our most creative cities - are able to do work which engages our creative faculties to some extent, whether as artists, musicians, writers, techies, innovators, entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, journalists or educators - those of us who work with our minds. That leaves a group that I term "the other 66 percent," who toil in low-wage rote and rotten jobs — if they have jobs at all — in which their creativity is subjugated, ignored or wasted.

Creativity itself is not in danger. It's flourishing is all around us - in science and technology, arts and culture, in our rapidly revitalizing cities. But we still have a long way to go if we want to build a truly creative society that supports and rewards the creativity of each and every one of us.

Q.

The author uses 'ironic' in the third paragraph to point out that

Creativity is at once our most precious resource and our most inexhaustible one. As anyone who has ever spent any time with children knows, every single human being is born creative; every human being is innately endowed with the ability to combine and recombine data, perceptions, materials and ideas, and devise new ways of thinking and doing. What fosters creativity? More than anything else: the presence of other creative people. The big myth is that creativity is the province of great individual geniuses. In fact creativity is a social process. Our biggest creative breakthroughs come when people learn from, compete with, and collaborate with other people.

Cities are the true fonts of creativity... With their diverse populations, dense social networks, and public spaces where people can meet spontaneously and serendipitously, they spark and catalyze new ideas. With their infrastructure for finance, organization and trade, they allow those ideas to be swiftly actualized.

As for what staunches creativity, that's easy, if ironic. It's the very institutions that we build to manage, exploit and perpetuate the fruits of creativity — our big bureaucracies, and sad to say, too many of our schools. Creativity is disruptive; schools and organizations are regimented, standardized and stultifying.

The education expert Sir Ken Robinson points to a 1968 study reporting on a group of 1,600 children who were tested over time for their ability to think in out-of-the-box ways. When the children were between 3 and 5 years old, 98 percent achieved positive scores. When they were 8 to 10, only 32 percent passed the same test, and only 10 percent at 13 to 15. When 280,000 25-year-olds took the test, just 2 percent passed. By the time we are adults, our creativity has been wrung out of us.

I once asked the great urbanist Jane Jacobs what makes some places more creative than others. She said, essentially, that the question was an easy one. All cities, she said, were filled with creative people; that's our default state as people. But some cities had more than their shares of leaders, people and institutions that blocked out that creativity. She called them "squelchers."

Creativity (or the lack of it) follows the same general contours of the great socio-economic divide - our rising inequality - that plagues us. According to my own estimates, roughly a third of us across the United States, and perhaps as much as half of us in our most creative cities - are able to do work which engages our creative faculties to some extent, whether as artists, musicians, writers, techies, innovators, entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, journalists or educators - those of us who work with our minds. That leaves a group that I term "the other 66 percent," who toil in low-wage rote and rotten jobs — if they have jobs at all — in which their creativity is subjugated, ignored or wasted.

Creativity itself is not in danger. It's flourishing is all around us - in science and technology, arts and culture, in our rapidly revitalizing cities. But we still have a long way to go if we want to build a truly creative society that supports and rewards the creativity of each and every one of us.

Q.

The central idea of this passage is that Options :

Creativity is at once our most precious resource and our most inexhaustible one. As anyone who has ever spent any time with children knows, every single human being is born creative; every human being is innately endowed with the ability to combine and recombine data, perceptions, materials and ideas, and devise new ways of thinking and doing. What fosters creativity? More than anything else: the presence of other creative people. The big myth is that creativity is the province of great individual geniuses. In fact creativity is a social process. Our biggest creative breakthroughs come when people learn from, compete with, and collaborate with other people.

Cities are the true fonts of creativity... With their diverse populations, dense social networks, and public spaces where people can meet spontaneously and serendipitously, they spark and catalyze new ideas. With their infrastructure for finance, organization and trade, they allow those ideas to be swiftly actualized.

As for what staunches creativity, that's easy, if ironic. It's the very institutions that we build to manage, exploit and perpetuate the fruits of creativity — our big bureaucracies, and sad to say, too many of our schools. Creativity is disruptive; schools and organizations are regimented, standardized and stultifying.

The education expert Sir Ken Robinson points to a 1968 study reporting on a group of 1,600 children who were tested over time for their ability to think in out-of-the-box ways. When the children were between 3 and 5 years old, 98 percent achieved positive scores. When they were 8 to 10, only 32 percent passed the same test, and only 10 percent at 13 to 15. When 280,000 25-year-olds took the test, just 2 percent passed. By the time we are adults, our creativity has been wrung out of us.

I once asked the great urbanist Jane Jacobs what makes some places more creative than others. She said, essentially, that the question was an easy one. All cities, she said, were filled with creative people; that's our default state as people. But some cities had more than their shares of leaders, people and institutions that blocked out that creativity. She called them "squelchers."

Creativity (or the lack of it) follows the same general contours of the great socio-economic divide - our rising inequality - that plagues us. According to my own estimates, roughly a third of us across the United States, and perhaps as much as half of us in our most creative cities - are able to do work which engages our creative faculties to some extent, whether as artists, musicians, writers, techies, innovators, entrepreneurs, doctors, lawyers, journalists or educators - those of us who work with our minds. That leaves a group that I term "the other 66 percent," who toil in low-wage rote and rotten jobs — if they have jobs at all — in which their creativity is subjugated, ignored or wasted.

Creativity itself is not in danger. It's flourishing is all around us - in science and technology, arts and culture, in our rapidly revitalizing cities. But we still have a long way to go if we want to build a truly creative society that supports and rewards the creativity of each and every one of us.

Q.

Jane Jacobs believed that cities that are more creative

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Today we can hardly conceive of ourselves without an unconscious. Yet between 1700 and 1900, this notion developed as a genuinely original thought. The “unconscious” burst the shell of conventional language, coined as it had been to embody the fleeting ideas and the shifting conceptions of several generations until, finally, it became fixed and defined in specialized terms within the realm of medical psychology and Freudian psychoanalysis.

The vocabulary concerning the soul and the mind increased enormously in the course of the nineteenth century. The enrichments of literary and intellectual language led to an altered understanding of the meanings that underlie time-honored expressions and traditional catchwords. At the same time, once coined, powerful new ideas attracted to themselves a whole host of seemingly unrelated issues, practices, and experiences, creating a peculiar network of preoccupations that as a group had not existed before. The drawn-out attempt to approach and define the unconscious brought together the spiritualist and the psychical researcher of borderline phenomena (such as apparitions, spectral illusions, haunted houses, mediums, trance, automatic writing); the psychiatrist or alienist probing the nature of mental disease, of abnormal ideation, hallucination, delirium, melancholia, mania; the surgeon performing operations with the aid of hypnotism; the magnetizer claiming to correct the disequilibrium in the universal flow of magnetic fluids but who soon came to be regarded as a clever manipulator of the imagination; the physiologist and the physician who puzzled over sleep, dreams, sleepwalking, anesthesia, the influence of the mind on the body in health and disease; the neurologist concerned with the functions of the brain and the physiological basis of mental life; the philosopher interested in the will, the emotions, consciousness, knowledge, imagination and the creative genius; and, last but not least, the psychologist.

Significantly, most if not all of these practices (for example, hypnotism in surgery or psychological magnetism) originated in the waning years of the eighteenth century and during the early decades of the nineteenth century, as did some of the disciplines (such as psychology and psychical research). The majority of topics too were either new or assumed hitherto unknown colors. Thus, before 1790, few if any spoke, in medical terms, of the affinity between creative genius and the hallucinations of the insane . . .

Striving vaguely and independently to give expression to a latent conception, various lines of thought can be brought together by some novel term. The new concept then serves as a kind of resting place or stocktaking in the development of ideas, giving satisfaction and a stimulus for further discussion or speculation. Thus, the massive introduction of the term unconscious by Hartmann in 1869 appeared to focalize many stray thoughts, affording a temporary feeling that a crucial step had been taken forward, a comprehensive knowledge gained, a knowledge that required only further elaboration, explication, and unfolding in order to bring in a bounty of higher understanding.

Ultimately, Hartmann’s attempt at defining the unconscious proved fruitless because he extended its reach into every realm of organic and inorganic, spiritual, intellectual, and instinctive existence, severely diluting the precision and compromising the impact of the concept.

Q. Which one of the following statements best describes what the passage is about?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Today we can hardly conceive of ourselves without an unconscious. Yet between 1700 and 1900, this notion developed as a genuinely original thought. The “unconscious” burst the shell of conventional language, coined as it had been to embody the fleeting ideas and the shifting conceptions of several generations until, finally, it became fixed and defined in specialized terms within the realm of medical psychology and Freudian psychoanalysis.

The vocabulary concerning the soul and the mind increased enormously in the course of the nineteenth century. The enrichments of literary and intellectual language led to an altered understanding of the meanings that underlie time-honored expressions and traditional catchwords. At the same time, once coined, powerful new ideas attracted to themselves a whole host of seemingly unrelated issues, practices, and experiences, creating a peculiar network of preoccupations that as a group had not existed before. The drawn-out attempt to approach and define the unconscious brought together the spiritualist and the psychical researcher of borderline phenomena (such as apparitions, spectral illusions, haunted houses, mediums, trance, automatic writing); the psychiatrist or alienist probing the nature of mental disease, of abnormal ideation, hallucination, delirium, melancholia, mania; the surgeon performing operations with the aid of hypnotism; the magnetizer claiming to correct the disequilibrium in the universal flow of magnetic fluids but who soon came to be regarded as a clever manipulator of the imagination; the physiologist and the physician who puzzled over sleep, dreams, sleepwalking, anesthesia, the influence of the mind on the body in health and disease; the neurologist concerned with the functions of the brain and the physiological basis of mental life; the philosopher interested in the will, the emotions, consciousness, knowledge, imagination and the creative genius; and, last but not least, the psychologist.

Significantly, most if not all of these practices (for example, hypnotism in surgery or psychological magnetism) originated in the waning years of the eighteenth century and during the early decades of the nineteenth century, as did some of the disciplines (such as psychology and psychical research). The majority of topics too were either new or assumed hitherto unknown colors. Thus, before 1790, few if any spoke, in medical terms, of the affinity between creative genius and the hallucinations of the insane . . .

Striving vaguely and independently to give expression to a latent conception, various lines of thought can be brought together by some novel term. The new concept then serves as a kind of resting place or stocktaking in the development of ideas, giving satisfaction and a stimulus for further discussion or speculation. Thus, the massive introduction of the term unconscious by Hartmann in 1869 appeared to focalize many stray thoughts, affording a temporary feeling that a crucial step had been taken forward, a comprehensive knowledge gained, a knowledge that required only further elaboration, explication, and unfolding in order to bring in a bounty of higher understanding.

Ultimately, Hartmann’s attempt at defining the unconscious proved fruitless because he extended its reach into every realm of organic and inorganic, spiritual, intellectual, and instinctive existence, severely diluting the precision and compromising the impact of the concept.

Q. “The enrichments of literary and intellectual language led to an altered understanding of the meanings that underlie timehonored expressions and traditional catchwords.” Which one of the following interpretations of this sentence would be closest in meaning to the original?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Today we can hardly conceive of ourselves without an unconscious. Yet between 1700 and 1900, this notion developed as a genuinely original thought. The “unconscious” burst the shell of conventional language, coined as it had been to embody the fleeting ideas and the shifting conceptions of several generations until, finally, it became fixed and defined in specialized terms within the realm of medical psychology and Freudian psychoanalysis.

The vocabulary concerning the soul and the mind increased enormously in the course of the nineteenth century. The enrichments of literary and intellectual language led to an altered understanding of the meanings that underlie time-honored expressions and traditional catchwords. At the same time, once coined, powerful new ideas attracted to themselves a whole host of seemingly unrelated issues, practices, and experiences, creating a peculiar network of preoccupations that as a group had not existed before. The drawn-out attempt to approach and define the unconscious brought together the spiritualist and the psychical researcher of borderline phenomena (such as apparitions, spectral illusions, haunted houses, mediums, trance, automatic writing); the psychiatrist or alienist probing the nature of mental disease, of abnormal ideation, hallucination, delirium, melancholia, mania; the surgeon performing operations with the aid of hypnotism; the magnetizer claiming to correct the disequilibrium in the universal flow of magnetic fluids but who soon came to be regarded as a clever manipulator of the imagination; the physiologist and the physician who puzzled over sleep, dreams, sleepwalking, anesthesia, the influence of the mind on the body in health and disease; the neurologist concerned with the functions of the brain and the physiological basis of mental life; the philosopher interested in the will, the emotions, consciousness, knowledge, imagination and the creative genius; and, last but not least, the psychologist.

Significantly, most if not all of these practices (for example, hypnotism in surgery or psychological magnetism) originated in the waning years of the eighteenth century and during the early decades of the nineteenth century, as did some of the disciplines (such as psychology and psychical research). The majority of topics too were either new or assumed hitherto unknown colors. Thus, before 1790, few if any spoke, in medical terms, of the affinity between creative genius and the hallucinations of the insane . . .

Striving vaguely and independently to give expression to a latent conception, various lines of thought can be brought together by some novel term. The new concept then serves as a kind of resting place or stocktaking in the development of ideas, giving satisfaction and a stimulus for further discussion or speculation. Thus, the massive introduction of the term unconscious by Hartmann in 1869 appeared to focalize many stray thoughts, affording a temporary feeling that a crucial step had been taken forward, a comprehensive knowledge gained, a knowledge that required only further elaboration, explication, and unfolding in order to bring in a bounty of higher understanding.

Ultimately, Hartmann’s attempt at defining the unconscious proved fruitless because he extended its reach into every realm of organic and inorganic, spiritual, intellectual, and instinctive existence, severely diluting the precision and compromising the impact of the concept.

Q. Which one of the following sets of words is closest to mapping the main arguments of the passage?

The passage below is accompanied by a set of questions. Choose the best answer to each question.

Today we can hardly conceive of ourselves without an unconscious. Yet between 1700 and 1900, this notion developed as a genuinely original thought. The “unconscious” burst the shell of conventional language, coined as it had been to embody the fleeting ideas and the shifting conceptions of several generations until, finally, it became fixed and defined in specialized terms within the realm of medical psychology and Freudian psychoanalysis.

The vocabulary concerning the soul and the mind increased enormously in the course of the nineteenth century. The enrichments of literary and intellectual language led to an altered understanding of the meanings that underlie time-honored expressions and traditional catchwords. At the same time, once coined, powerful new ideas attracted to themselves a whole host of seemingly unrelated issues, practices, and experiences, creating a peculiar network of preoccupations that as a group had not existed before. The drawn-out attempt to approach and define the unconscious brought together the spiritualist and the psychical researcher of borderline phenomena (such as apparitions, spectral illusions, haunted houses, mediums, trance, automatic writing); the psychiatrist or alienist probing the nature of mental disease, of abnormal ideation, hallucination, delirium, melancholia, mania; the surgeon performing operations with the aid of hypnotism; the magnetizer claiming to correct the disequilibrium in the universal flow of magnetic fluids but who soon came to be regarded as a clever manipulator of the imagination; the physiologist and the physician who puzzled over sleep, dreams, sleepwalking, anesthesia, the influence of the mind on the body in health and disease; the neurologist concerned with the functions of the brain and the physiological basis of mental life; the philosopher interested in the will, the emotions, consciousness, knowledge, imagination and the creative genius; and, last but not least, the psychologist.

Significantly, most if not all of these practices (for example, hypnotism in surgery or psychological magnetism) originated in the waning years of the eighteenth century and during the early decades of the nineteenth century, as did some of the disciplines (such as psychology and psychical research). The majority of topics too were either new or assumed hitherto unknown colors. Thus, before 1790, few if any spoke, in medical terms, of the affinity between creative genius and the hallucinations of the insane . . .

Striving vaguely and independently to give expression to a latent conception, various lines of thought can be brought together by some novel term. The new concept then serves as a kind of resting place or stocktaking in the development of ideas, giving satisfaction and a stimulus for further discussion or speculation. Thus, the massive introduction of the term unconscious by Hartmann in 1869 appeared to focalize many stray thoughts, affording a temporary feeling that a crucial step had been taken forward, a comprehensive knowledge gained, a knowledge that required only further elaboration, explication, and unfolding in order to bring in a bounty of higher understanding.

Ultimately, Hartmann’s attempt at defining the unconscious proved fruitless because he extended its reach into every realm of organic and inorganic, spiritual, intellectual, and instinctive existence, severely diluting the precision and compromising the impact of the concept.

Q. All of the following statements may be considered valid inferences from the passage, EXCEPT:

Directions: Rearrange the following five sentences (A), (B), (C), (D) and (E) in the proper sequence to form a meaningful paragraph and then answer the given question.

A. At just over 260 cubic km per year, the country uses 25 percent of all groundwater extracted globally, ahead of the USA and China.

B. And because 70 percent of the water supply in agriculture today is groundwater, it will remain the lifeline of India's water supplies for years to come.

C. Despite this, we have an extremely poor understanding of groundwater, which impacts both policy and practice.

D. A majority of India's water problems are those relating to groundwater—water that is found beneath the earth's surface.

E. This is because we are the largest user of groundwater in the world, and therefore highly dependent on it.

Which of the following is the FIRST sentence of the sequence?

Which of the following four sentence is grammatically correct?

Direction: Spot the grammatical errors in the given sentence. Mark the part with error as your answer. If there is no error, mark "No error" as the answer. (Ignore punctuation error)

A recycling plant in close proximity to (a)/ the residential area can post (b)/ serious threats from residents (c)/ by leaving behind persistent pollutants. (d)/ No error (e)

An old woman had the following assets:

(a) Rs. 70 lakh in bank deposits

(b) 1 house worth Rs. 50 lakh

(c) 3 flats, each worth Rs. 30 lakh

(d) Certain number of gold coins, each worth Rs. 1 lakh

She wanted to distribute her assets among her three children; Neeta, Seeta and Geeta.

The house, any of the flats or any of the coins were not to be split. That is, the house went entirely to one child; a flat went to one child and similarly, a gold coin went to one child

Q.

Among the three, Neeta received the least amount in bank deposits, while Geeta received the highest. The value of the assets was distributed equally among the children, as were the gold coins.

How much did Seeta receive in bank deposits (in lakhs of rupees)?

An old woman had the following assets:

(a) Rs. 70 lakh in bank deposits

(b) 1 house worth Rs. 50 lakh

(c) 3 flats, each worth Rs. 30 lakh

(d) Certain number of gold coins, each worth Rs. 1 lakh

She wanted to distribute her assets among her three children; Neeta, Seeta and Geeta.

The house, any of the flats or any of the coins were not to be split. That is, the house went entirely to one child; a flat went to one child and similarly, a gold coin went to one child

Q.

Among the three, Neeta received the least amount in hank deposits, while Geeta received the hig: of the assets was distributed equally among the children, as were the gold coins.

How many flats did Neeta receive?

An old woman had the following assets:

(a) Rs. 70 lakh in bank deposits

(b) 1 house worth Rs. 50 lakh

(c) 3 flats, each worth Rs. 30 lakh

(d) Certain number of gold coins, each worth Rs. 1 lakh

She wanted to distribute her assets among her three children; Neeta, Seeta and Geeta.

The house, any of the flats or any of the coins were not to be split. That is, the house went entirely to one child; a flat went to one child and similarly, a gold coin went to one child

Q.

The value of the assets distributed among Neeta, Seeta and Geeta was in the ratio of 1:2:3, while the gold coins were distributed among them in the ratio of 2:3:4. One child got all three flats and she did not get the house. One child, other than Geeta, got Rs. 30 lakh in bank deposits.

How many gold coins did the old woman have?

An old woman had the following assets:

(a) Rs. 70 lakh in bank deposits

(b) 1 house worth Rs. 50 lakh

(c) 3 flats, each worth Rs. 30 lakh

(d) Certain number of gold coins, each worth Rs. 1 lakh

She wanted to distribute her assets among her three children; Neeta, Seeta and Geeta.

The house, any of the flats or any of the coins were not to be split. That is, the house went entirely to one child; a flat went to one child and similarly, a gold coin went to one child

Q.

The value of the assets distributed among Neeta, Seeta and Geeta was in the ratio of 1:2:3, while the gold coins were distributed among them in the ratio of 2:3:4. One child got all three flats and she did not get the house. One child, other than Geeta, got Rs. 30 lakh in bank deposits.

How much did Geeta get in bank deposits (in lakhs of rupees)?

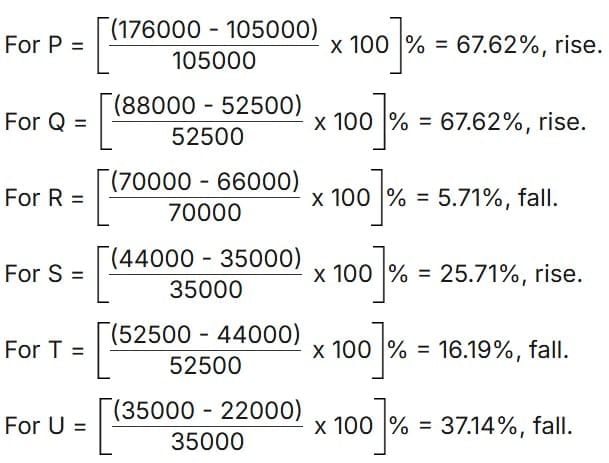

What was the difference in the number of Q type cars produced in 2000 and that produced in 2001?

Total number of cars of models P, Q and T manufactured in 2000 is?

If the percentage production of P type cars in 2001 was the same as that in 2000, then the number of P type cars produced in 2001 would have been?

If 85% of the S type cars produced in each year were sold by the company, how many S type cars remain unsold?

For which model the percentage rise/fall in production from 2000 to 2001 was minimum?

Let a, b, m and n be natural numbers such that a > 1 and b > 1. If ambn = 144145, then the largest possible value of n - m is

Directions for Question : A set of 10 pipes (set X) can fill 70% of a tank in 7 minutes. Another set of 5 pipes (set Y) fills 3/8 of the tank in 3 minutes. A third set of 8 pipes (set Z) can empty 5/10 of the tank in 10 minutes.

Q. If only half the pipes of set X are closed and only half the pipes of set Y are open and all other pipes are open, how long will it take to fill 49% of the tank?

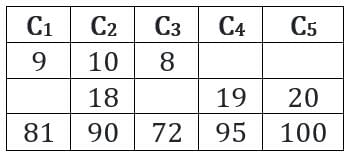

Suppose, C1, C2, C3, C4, and C5 are five companies. The profits made by C1, C2, and C3 are in the ratio 9 : 10 : 8 while the profits made by C2, C4, and C5 are in the ratio 18 : 19 : 20. If C5 has made a profit of Rs 19 crore more than C1, then the total profit (in Rs) made by all five companies is:

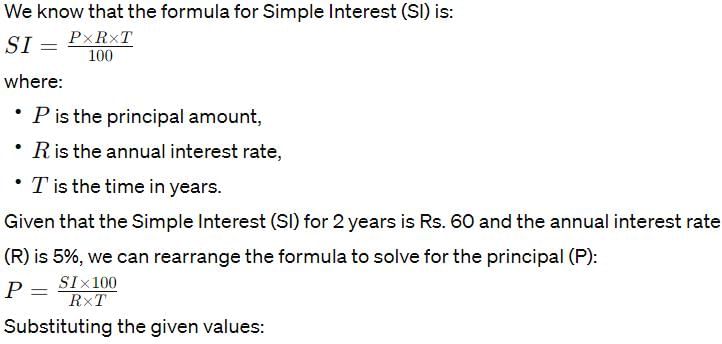

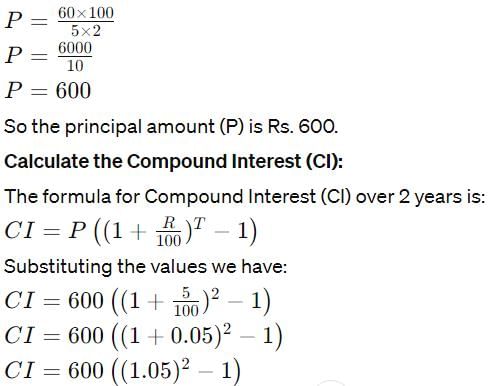

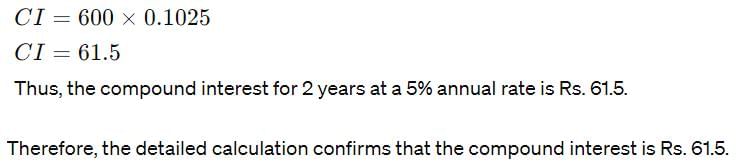

If the simple interest on a sum of money for 2 years at 5% per annum is Rs. 60, what is the compound interest on the same at the same rate and for the same time?

Q. A man takes 5 hours 45 min in walking to a certain place and riding back. He would have gained 2 hours by riding both ways. The time he would take to walk both ways, is:

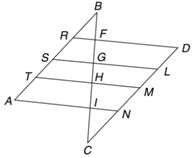

In the figure, AB is parallel to CD and RD || SL || TM || AN, and BR : RS : ST : TA = 3 : 5 : 2 : 7. If it is known that CN = 1.333 BR. Find the ratio of BF : FG : GH : HI : IC

If a lemon and apple together costs Rs. 12, a tomato and lemon cost Rs.4 and an apple cost of Rs.8 more than a tomato or a lemon, then which of the following can be the price of lemon?

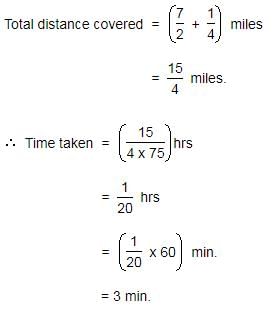

A train having a length of 1/4 mile , is traveling at a speed of 75 mph. It enters a tunnel 3 ½ miles long. How long does it take the train to pass through the tunnel from the moment the front enters to the moment the rear emerges?

Q.

Two ships are sailing in the sea on the two sides of a lighthouse. The angle of elevation of the top of the lighthouse is observed from the ships are 30° and 45° respectively. If the lighthouse is 100 m high, the distance between the two ships is:

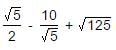

Total number of S type cars which remained unsold

Total number of S type cars which remained unsold

is equal to:

is equal to: