IIFT Mock Test - 4 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 4 (New Pattern)

Choose one of the following options that means the opposite of the given word.

Copious

He is the black sheep of the family is an example of:

Which one of the following statements is grammatically incorrect?

Select the phrase which is closest in meaning to the given phrase.

To be off your head means:

Select the word to replace the blank spaces.

Troubled : Distraught :: Tranquil :______

Arrange the sentences in the most logical sequence:

(i) Examples of this are the logical classification of ragas into melakarthas, and the use of fixed compositions similar to Western classical music.

(ii) Carnatic music, from South India, tends to be more rhythmically intensive and structured than Hindustani music.

(iii) In addition, accompanists have a much larger role in Carnatic concerts than in Hindustani concerts.

(iv) Carnatic raga elaborations are generally much faster in tempo and shorter than their equivalents in Hindustani music.

For each of the questions below, select the word that fits well in all the four sentences.

While I sympathized in concept, the very nature of Howie's capabilities were so awesome to me, I couldn't ______ the ramifications of broadening them.

He couldn't _______ of some jurisdiction now part of a larger database wanting Fred for past sins.

I am certain you cannot ______ a place so charming as the Valley of Ooty.

The situation, we _______, is one which, if for a moment good sense and good feeling could come into play between the contending parties, might be turned to advantage.

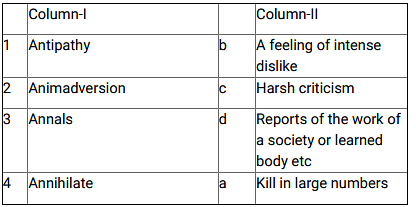

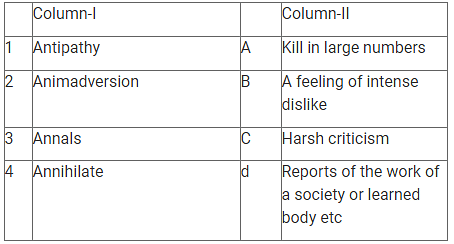

Match the word in column 1 with the word in column 2.

Select the most appropriate antonym for the given word.

Ignominy

Which one of the following statements is grammatically correct?

Select the phrase which is closest in meaning to the given phrase.

To come in from the cold means:

Answer the questions that follow with the appropriate choice of word.

Identify the word that would best fit a characteristic of judge.

Select the word to replace the blank spaces.

Audacious : Trepidation :: Laconic :_______

Arrange the sentences in the most logical sequence:

(i) Della finished her cry and attended to her cheeks with the powder rag.

(ii) Tomorrow would be Christmas Day, and she had only $1.87 with which to buy Jim a present.

(iii) She stood by the window and looked out dully at a grey cat walking a grey fence in a grey backyard.

(iv) She had been saving every penny she could for months, with this result.

For each of the questions below, select the word that fits well in all the four sentences.

For some reason she had always thought Alex would ______ quickly to any lifestyle.

In the meantime, I've got to run out this morning to meet with my financial manager to ______ my plan now that I'm happily unemployed.

Banks will be subject to new restraints on lending but will have more than eight years to ______, which is longer than anticipated.

Every time the weather got cold outside, other residents in the complex cranked their heaters up and then he had to _______ his own thermostat.

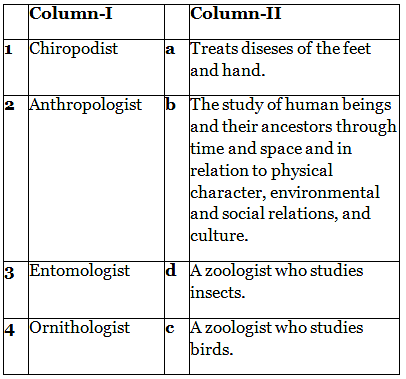

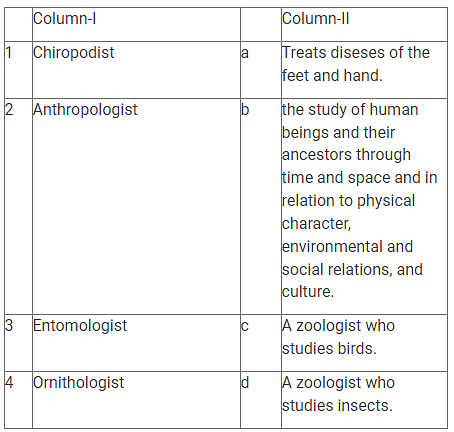

Match the word in column 1 with the word in column 2.

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given.

It was my duty to shoot, and I don't regret it. The woman was already dead. I was just making sure she didn't take any Marines with her. It was clear that not only did she want to kill them, but she didn't care about anybody else nearby who would have been blown up by the grenade or killed in the firefight. Children on the street, people in the houses, maybe her child.

She was too blinded by evil to consider them. She just wanted Americans dead, no matter what. My shots saved several Americans, whose lives were clearly worth more than that woman's twisted soul. I can stand before God with a clear conscience about doing my job. But I truly, deeply hated the evil that woman possessed. I hate it to this day. Savage, despicable evil. That's what we were fighting in Iraq. That's why a lot of people, myself included, called the enemy "savages." There really was no other way to describe what we encountered there.

People ask me all the time, "How many people have you killed?" My standard response is, "Does the answer make me less, or more, of a man?". The number is not important to me. I only wish I had killed more. Not for bragging rights, but because I believe the world is a better place without savages out there taking American lives. Everyone I shot in Iraq was trying to harm Americans or Iraqis loyal to the new government. I had a job to do as a SEAL. I killed the enemy - an enemy I saw day in and day out plotting to kill my fellow Americans. I'm haunted by the enemy's successes. They were few, but even a single American life is one too many lost. I don't worry about what other people think of me. It's one of the things I most admired about my dad growing up. He didn't give a hoot what others thought. He was who he was. It's one of the qualities that has kept me most sane.

I'm still a bit uncomfortable with the idea of publishing my life story. First of all, I've always thought that if you want to know what life as a SEAL is like, you should go get your own Trident: earn our medal, the symbol of who we are. Go through our training, make the sacrifices, physical and mental. That's the only way you'll know.

Second of all, and more importantly, who cares about my life? I'm no different than anyone else. I happen to have been in some pretty grave situations. People have told me it's interesting. I don't see it. Other people are talking about writing books about my life, or about some of the things I've done. I find it strange, but I also feel it's my life and my story, and I guess I better be the one to get it on paper the way it actually happened.

Also, there are a lot of people who deserve credit, and if I don't write the story, they may be overlooked. I don't like the idea of that at all. My boys deserve to be praised more than I do. The Navy credits me with more kills as a sniper than any other American service member, past or present. I guess that's true. They go back and forth on what the number is. One week, it's 160 (the "official" number as of this writing, for what that's worth), then it's way higher, then it's somewhere in between. If you want a number, ask the Navy - you may even get the truth if you catch them on the right day.

People always want a number. Even if the Navy would let me, I'm not going to give one. I'm not a numbers guy. SEALs are silent warriors, and I'm a SEAL down to my soul. If you want the whole story, get a Trident. If you want to check me out, ask a SEAL. If you want what I am comfortable with sharing, and even some stuff I am reluctant to reveal, read on.

I've always said that I wasn't the best shot or even the best sniper ever. I'm not denigrating my skills. I certainly worked hard to hone them. I was blessed with some excellent instructors, who deserve a lot of credit. And my boys - the fellow SEALs and the Marines and the Army soldiers who fought with me and helped me do my job - were all a critical part of my success. But my high total and my so-called "legend" have much to do with the fact that I was in the action a lot.

In other words, I had more opportunities than most. I served back-to-back deployments from right before the Iraq War kicked off until the time I got out in 2009. I was lucky enough to be positioned directly in the action. There's another question people ask a lot: Did it bother you killing so many people in Iraq? I tell them, "No."

And I mean it. The first time you shoot someone, you get a little nervous. You think, can I really shoot this guy? Is it really okay? But after you kill your enemy, you see it's okay. You say, Great. You do it again. And again. You do it so the enemy won't kill you or your countrymen. You do it until there's no one left for you to kill. That's what war is. I loved what I did. I still do. If circumstances were different - if my family didn't need me - I'd be back in a heartbeat. I'm not lying or exaggerating to say it was fun. I had the time of my life being a SEAL.

People try to put me in a category as a dangerous, a good ol' boy, jerk, sniper, SEAL, and probably other categories not appropriate for print. All might be true on any given day. In the end, my story, in Iraq and afterward, is about more than just killing people or even fighting for my country. It's about being a man. And it's about love as well as hate.

Q. Why is the number of killings not important for the author?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given.

It was my duty to shoot, and I don't regret it. The woman was already dead. I was just making sure she didn't take any Marines with her. It was clear that not only did she want to kill them, but she didn't care about anybody else nearby who would have been blown up by the grenade or killed in the firefight. Children on the street, people in the houses, maybe her child.

She was too blinded by evil to consider them. She just wanted Americans dead, no matter what. My shots saved several Americans, whose lives were clearly worth more than that woman's twisted soul. I can stand before God with a clear conscience about doing my job. But I truly, deeply hated the evil that woman possessed. I hate it to this day. Savage, despicable evil. That's what we were fighting in Iraq. That's why a lot of people, myself included, called the enemy "savages." There really was no other way to describe what we encountered there.

People ask me all the time, "How many people have you killed?" My standard response is, "Does the answer make me less, or more, of a man?". The number is not important to me. I only wish I had killed more. Not for bragging rights, but because I believe the world is a better place without savages out there taking American lives. Everyone I shot in Iraq was trying to harm Americans or Iraqis loyal to the new government. I had a job to do as a SEAL. I killed the enemy - an enemy I saw day in and day out plotting to kill my fellow Americans. I'm haunted by the enemy's successes. They were few, but even a single American life is one too many lost. I don't worry about what other people think of me. It's one of the things I most admired about my dad growing up. He didn't give a hoot what others thought. He was who he was. It's one of the qualities that has kept me most sane.

I'm still a bit uncomfortable with the idea of publishing my life story. First of all, I've always thought that if you want to know what life as a SEAL is like, you should go get your own Trident: earn our medal, the symbol of who we are. Go through our training, make the sacrifices, physical and mental. That's the only way you'll know.

Second of all, and more importantly, who cares about my life? I'm no different than anyone else. I happen to have been in some pretty grave situations. People have told me it's interesting. I don't see it. Other people are talking about writing books about my life, or about some of the things I've done. I find it strange, but I also feel it's my life and my story, and I guess I better be the one to get it on paper the way it actually happened.

Also, there are a lot of people who deserve credit, and if I don't write the story, they may be overlooked. I don't like the idea of that at all. My boys deserve to be praised more than I do. The Navy credits me with more kills as a sniper than any other American service member, past or present. I guess that's true. They go back and forth on what the number is. One week, it's 160 (the "official" number as of this writing, for what that's worth), then it's way higher, then it's somewhere in between. If you want a number, ask the Navy - you may even get the truth if you catch them on the right day.

People always want a number. Even if the Navy would let me, I'm not going to give one. I'm not a numbers guy. SEALs are silent warriors, and I'm a SEAL down to my soul. If you want the whole story, get a Trident. If you want to check me out, ask a SEAL. If you want what I am comfortable with sharing, and even some stuff I am reluctant to reveal, read on.

I've always said that I wasn't the best shot or even the best sniper ever. I'm not denigrating my skills. I certainly worked hard to hone them. I was blessed with some excellent instructors, who deserve a lot of credit. And my boys - the fellow SEALs and the Marines and the Army soldiers who fought with me and helped me do my job - were all a critical part of my success. But my high total and my so-called "legend" have much to do with the fact that I was in the action a lot.

In other words, I had more opportunities than most. I served back-to-back deployments from right before the Iraq War kicked off until the time I got out in 2009. I was lucky enough to be positioned directly in the action. There's another question people ask a lot: Did it bother you killing so many people in Iraq? I tell them, "No."

And I mean it. The first time you shoot someone, you get a little nervous. You think, can I really shoot this guy? Is it really okay? But after you kill your enemy, you see it's okay. You say, Great. You do it again. And again. You do it so the enemy won't kill you or your countrymen. You do it until there's no one left for you to kill. That's what war is. I loved what I did. I still do. If circumstances were different - if my family didn't need me - I'd be back in a heartbeat. I'm not lying or exaggerating to say it was fun. I had the time of my life being a SEAL.

People try to put me in a category as a dangerous, a good ol' boy, jerk, sniper, SEAL, and probably other categories not appropriate for print. All might be true on any given day. In the end, my story, in Iraq and afterward, is about more than just killing people or even fighting for my country. It's about being a man. And it's about love as well as hate.

Q. Why does the author feel uncomfortable while publishing his story?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given.

It was my duty to shoot, and I don't regret it. The woman was already dead. I was just making sure she didn't take any Marines with her. It was clear that not only did she want to kill them, but she didn't care about anybody else nearby who would have been blown up by the grenade or killed in the firefight. Children on the street, people in the houses, maybe her child.

She was too blinded by evil to consider them. She just wanted Americans dead, no matter what. My shots saved several Americans, whose lives were clearly worth more than that woman's twisted soul. I can stand before God with a clear conscience about doing my job. But I truly, deeply hated the evil that woman possessed. I hate it to this day. Savage, despicable evil. That's what we were fighting in Iraq. That's why a lot of people, myself included, called the enemy "savages." There really was no other way to describe what we encountered there.

People ask me all the time, "How many people have you killed?" My standard response is, "Does the answer make me less, or more, of a man?". The number is not important to me. I only wish I had killed more. Not for bragging rights, but because I believe the world is a better place without savages out there taking American lives. Everyone I shot in Iraq was trying to harm Americans or Iraqis loyal to the new government. I had a job to do as a SEAL. I killed the enemy - an enemy I saw day in and day out plotting to kill my fellow Americans. I'm haunted by the enemy's successes. They were few, but even a single American life is one too many lost. I don't worry about what other people think of me. It's one of the things I most admired about my dad growing up. He didn't give a hoot what others thought. He was who he was. It's one of the qualities that has kept me most sane.

I'm still a bit uncomfortable with the idea of publishing my life story. First of all, I've always thought that if you want to know what life as a SEAL is like, you should go get your own Trident: earn our medal, the symbol of who we are. Go through our training, make the sacrifices, physical and mental. That's the only way you'll know.

Second of all, and more importantly, who cares about my life? I'm no different than anyone else. I happen to have been in some pretty grave situations. People have told me it's interesting. I don't see it. Other people are talking about writing books about my life, or about some of the things I've done. I find it strange, but I also feel it's my life and my story, and I guess I better be the one to get it on paper the way it actually happened.

Also, there are a lot of people who deserve credit, and if I don't write the story, they may be overlooked. I don't like the idea of that at all. My boys deserve to be praised more than I do. The Navy credits me with more kills as a sniper than any other American service member, past or present. I guess that's true. They go back and forth on what the number is. One week, it's 160 (the "official" number as of this writing, for what that's worth), then it's way higher, then it's somewhere in between. If you want a number, ask the Navy - you may even get the truth if you catch them on the right day.

People always want a number. Even if the Navy would let me, I'm not going to give one. I'm not a numbers guy. SEALs are silent warriors, and I'm a SEAL down to my soul. If you want the whole story, get a Trident. If you want to check me out, ask a SEAL. If you want what I am comfortable with sharing, and even some stuff I am reluctant to reveal, read on.

I've always said that I wasn't the best shot or even the best sniper ever. I'm not denigrating my skills. I certainly worked hard to hone them. I was blessed with some excellent instructors, who deserve a lot of credit. And my boys - the fellow SEALs and the Marines and the Army soldiers who fought with me and helped me do my job - were all a critical part of my success. But my high total and my so-called "legend" have much to do with the fact that I was in the action a lot.

In other words, I had more opportunities than most. I served back-to-back deployments from right before the Iraq War kicked off until the time I got out in 2009. I was lucky enough to be positioned directly in the action. There's another question people ask a lot: Did it bother you killing so many people in Iraq? I tell them, "No."

And I mean it. The first time you shoot someone, you get a little nervous. You think, can I really shoot this guy? Is it really okay? But after you kill your enemy, you see it's okay. You say, Great. You do it again. And again. You do it so the enemy won't kill you or your countrymen. You do it until there's no one left for you to kill. That's what war is. I loved what I did. I still do. If circumstances were different - if my family didn't need me - I'd be back in a heartbeat. I'm not lying or exaggerating to say it was fun. I had the time of my life being a SEAL.

People try to put me in a category as a dangerous, a good ol' boy, jerk, sniper, SEAL, and probably other categories not appropriate for print. All might be true on any given day. In the end, my story, in Iraq and afterward, is about more than just killing people or even fighting for my country. It's about being a man. And it's about love as well as hate.

Q. What is the number of kills that the author has achieved?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given.

It was my duty to shoot, and I don't regret it. The woman was already dead. I was just making sure she didn't take any Marines with her. It was clear that not only did she want to kill them, but she didn't care about anybody else nearby who would have been blown up by the grenade or killed in the firefight. Children on the street, people in the houses, maybe her child.

She was too blinded by evil to consider them. She just wanted Americans dead, no matter what. My shots saved several Americans, whose lives were clearly worth more than that woman's twisted soul. I can stand before God with a clear conscience about doing my job. But I truly, deeply hated the evil that woman possessed. I hate it to this day. Savage, despicable evil. That's what we were fighting in Iraq. That's why a lot of people, myself included, called the enemy "savages." There really was no other way to describe what we encountered there.

People ask me all the time, "How many people have you killed?" My standard response is, "Does the answer make me less, or more, of a man?". The number is not important to me. I only wish I had killed more. Not for bragging rights, but because I believe the world is a better place without savages out there taking American lives. Everyone I shot in Iraq was trying to harm Americans or Iraqis loyal to the new government. I had a job to do as a SEAL. I killed the enemy - an enemy I saw day in and day out plotting to kill my fellow Americans. I'm haunted by the enemy's successes. They were few, but even a single American life is one too many lost. I don't worry about what other people think of me. It's one of the things I most admired about my dad growing up. He didn't give a hoot what others thought. He was who he was. It's one of the qualities that has kept me most sane.

I'm still a bit uncomfortable with the idea of publishing my life story. First of all, I've always thought that if you want to know what life as a SEAL is like, you should go get your own Trident: earn our medal, the symbol of who we are. Go through our training, make the sacrifices, physical and mental. That's the only way you'll know.

Second of all, and more importantly, who cares about my life? I'm no different than anyone else. I happen to have been in some pretty grave situations. People have told me it's interesting. I don't see it. Other people are talking about writing books about my life, or about some of the things I've done. I find it strange, but I also feel it's my life and my story, and I guess I better be the one to get it on paper the way it actually happened.

Also, there are a lot of people who deserve credit, and if I don't write the story, they may be overlooked. I don't like the idea of that at all. My boys deserve to be praised more than I do. The Navy credits me with more kills as a sniper than any other American service member, past or present. I guess that's true. They go back and forth on what the number is. One week, it's 160 (the "official" number as of this writing, for what that's worth), then it's way higher, then it's somewhere in between. If you want a number, ask the Navy - you may even get the truth if you catch them on the right day.

People always want a number. Even if the Navy would let me, I'm not going to give one. I'm not a numbers guy. SEALs are silent warriors, and I'm a SEAL down to my soul. If you want the whole story, get a Trident. If you want to check me out, ask a SEAL. If you want what I am comfortable with sharing, and even some stuff I am reluctant to reveal, read on.

I've always said that I wasn't the best shot or even the best sniper ever. I'm not denigrating my skills. I certainly worked hard to hone them. I was blessed with some excellent instructors, who deserve a lot of credit. And my boys - the fellow SEALs and the Marines and the Army soldiers who fought with me and helped me do my job - were all a critical part of my success. But my high total and my so-called "legend" have much to do with the fact that I was in the action a lot.

In other words, I had more opportunities than most. I served back-to-back deployments from right before the Iraq War kicked off until the time I got out in 2009. I was lucky enough to be positioned directly in the action. There's another question people ask a lot: Did it bother you killing so many people in Iraq? I tell them, "No."

And I mean it. The first time you shoot someone, you get a little nervous. You think, can I really shoot this guy? Is it really okay? But after you kill your enemy, you see it's okay. You say, Great. You do it again. And again. You do it so the enemy won't kill you or your countrymen. You do it until there's no one left for you to kill. That's what war is. I loved what I did. I still do. If circumstances were different - if my family didn't need me - I'd be back in a heartbeat. I'm not lying or exaggerating to say it was fun. I had the time of my life being a SEAL.

People try to put me in a category as a dangerous, a good ol' boy, jerk, sniper, SEAL, and probably other categories not appropriate for print. All might be true on any given day. In the end, my story, in Iraq and afterward, is about more than just killing people or even fighting for my country. It's about being a man. And it's about love as well as hate.

What does the author mean by 'the woman was already dead'?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Let's be honest: The change has been coming for a while. Reality television has inserted itself into the field of psychology as countless shows over the years have begun to use psychotherapists as a part of their cast. Therapy has long been a subject of at least mild intrigue because what is said to the therapist behind closed doors - well, one never really knows unless you're either the client or the therapist. For the most part, the psychotherapy room has historically acted as a sacred chamber, the rare place where the client feels safe and listened to, and the therapist acts as the supportive mirror, guide, and confidant.

The first reality show I ever saw which a therapist, Breaking Bonaduce (2005), had focused on the life of former TV star Danny Bonaduce. I remember thinking at the time how unusual it was that a therapist was actually having a session with clients - drumroll...and cameras! - in the same room. Back then, I didn't think too much of it, probably dismissing psychotherapy on TV as a passing fad. (It is worth mentioning, however, that the therapy I saw conducted on the show was actually pretty good.) Over the years, we have seen more therapists in reality television and audiences have sat through excerpts of more therapy sessions than I can - or want to - count. As the medium of TV therapy has become more common - heck, even expected on your average reality show - it's caused me to reflect on 1) what possesses the clients to be interested in venting their problems in such a public way, and 2) what possesses the therapists to want to show the therapy with their clients on TV. When it comes to the clients' motivations, I have heard many people say, "Oh, they just want attention." First, I'm not sure it's that simple.

I give psychotherapy clients an awful lot of credit for having the strength and courage to work on their issues, and I see it as my job as a therapist to protect them and their (often potentially) vulnerable feelings. Even if a client of mine said he wanted to appear on television in a therapy session, I'd have to really think about whether it would be good for him or her. Perhaps for some it would be okay, while it would be problematic for others? My sense, although no one can say for sure, is that it is probably ideal for a client to discuss their issues with the world later, once they're out of the woods and can look back on a hard time with the solace of knowing they're stronger now. Nevertheless, I've worked with clients on talk shows (e.g., The Doctors) where cameras documented their issues (e.g., problems with road rage) as well as my interventions to help them. In some ways, that's not so different from reality TV therapy, right?

Which brings us to L.A. Shrinks, the new show on BRAVO. The show, instead of focusing exclusively on the lives of the clients, also focuses on three therapists and - wait for it - their private lives! The show gives the audience a backstage pass into the personal lives of the therapists, and includes footage of emotional and dramatic moments for each of the therapists. Quite honestly, this show takes psychotherapists on television to another level. Incidentally, casting people for the show contacted me a while ago and asked me if I would be interested in trying out for the show. I said "no" because the idea of the show confused me: Would it bring the usual magic of reality TV, replete with crafted editing that makes the therapists look nuts? Would my clients end up feeling exploited? I felt instantly protective of the profession of psychology and psychotherapy, as well as the clients who seek it out.

The truth is that good therapy is one of the most wonderful and life-changing experiences a person can have, and I hate to think that therapy will ultimately seem like a dog-and-pony show that's full of emotional fireworks or, God forbid, turning over tables, which occurred on a Real Housewives of New Jersey episode on the same network. Simply put, the show worries me for fear of the reputation of psychotherapy. I can see both positives and negatives to showing excerpts of therapy sessions, provided that the client and therapist and doing it for the right reasons: plain and simple, to help themselves and show the viewing audience that they can get good help, too. So, what about showing the private lives of therapists? With that, too, I can see the positives and negatives.

Because there is a power differential between a therapist and a client, the client can sometimes idealize the therapist, despite the fact that the client consciously understands the therapist is a real person, with faults and all like everybody else. Unconsciously, however, the power differential can cause the client to see the therapist as perfectly well balanced, and that's never true. In this way, showing the real-life side of the therapist can be a positive. But we're talking about reality TV here, so we must discuss the possibility that the therapists might end up looking a little unprofessional or, worse, insane in the membrane. (Remember that song from the 90s?)

The greatest possible danger in showcasing the lives of therapists is that the focus on the therapist takes the focus away from the client. It's hard to say where the future reputation of psychotherapy is headed given its new incarnations (reality TV, telemedicine, and even online therapy), but talking about it as a professional community is important. After all, we need to practice what we preach to our clients: It's all about insight and understanding the motivations.

Q. In what context does the author use the phrase "a dog-and-pony show"?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Let's be honest: The change has been coming for a while. Reality television has inserted itself into the field of psychology as countless shows over the years have begun to use psychotherapists as a part of their cast. Therapy has long been a subject of at least mild intrigue because what is said to the therapist behind closed doors - well, one never really knows unless you're either the client or the therapist. For the most part, the psychotherapy room has historically acted as a sacred chamber, the rare place where the client feels safe and listened to, and the therapist acts as the supportive mirror, guide, and confidant.

The first reality show I ever saw which a therapist, Breaking Bonaduce (2005), had focused on the life of former TV star Danny Bonaduce. I remember thinking at the time how unusual it was that a therapist was actually having a session with clients - drumroll...and cameras! - in the same room. Back then, I didn't think too much of it, probably dismissing psychotherapy on TV as a passing fad. (It is worth mentioning, however, that the therapy I saw conducted on the show was actually pretty good.) Over the years, we have seen more therapists in reality television and audiences have sat through excerpts of more therapy sessions than I can - or want to - count. As the medium of TV therapy has become more common - heck, even expected on your average reality show - it's caused me to reflect on 1) what possesses the clients to be interested in venting their problems in such a public way, and 2) what possesses the therapists to want to show the therapy with their clients on TV. When it comes to the clients' motivations, I have heard many people say, "Oh, they just want attention." First, I'm not sure it's that simple.

I give psychotherapy clients an awful lot of credit for having the strength and courage to work on their issues, and I see it as my job as a therapist to protect them and their (often potentially) vulnerable feelings. Even if a client of mine said he wanted to appear on television in a therapy session, I'd have to really think about whether it would be good for him or her. Perhaps for some it would be okay, while it would be problematic for others? My sense, although no one can say for sure, is that it is probably ideal for a client to discuss their issues with the world later, once they're out of the woods and can look back on a hard time with the solace of knowing they're stronger now. Nevertheless, I've worked with clients on talk shows (e.g., The Doctors) where cameras documented their issues (e.g., problems with road rage) as well as my interventions to help them. In some ways, that's not so different from reality TV therapy, right?

Which brings us to L.A. Shrinks, the new show on BRAVO. The show, instead of focusing exclusively on the lives of the clients, also focuses on three therapists and - wait for it - their private lives! The show gives the audience a backstage pass into the personal lives of the therapists, and includes footage of emotional and dramatic moments for each of the therapists. Quite honestly, this show takes psychotherapists on television to another level. Incidentally, casting people for the show contacted me a while ago and asked me if I would be interested in trying out for the show. I said "no" because the idea of the show confused me: Would it bring the usual magic of reality TV, replete with crafted editing that makes the therapists look nuts? Would my clients end up feeling exploited? I felt instantly protective of the profession of psychology and psychotherapy, as well as the clients who seek it out.

The truth is that good therapy is one of the most wonderful and life-changing experiences a person can have, and I hate to think that therapy will ultimately seem like a dog-and-pony show that's full of emotional fireworks or, God forbid, turning over tables, which occurred on a Real Housewives of New Jersey episode on the same network. Simply put, the show worries me for fear of the reputation of psychotherapy. I can see both positives and negatives to showing excerpts of therapy sessions, provided that the client and therapist and doing it for the right reasons: plain and simple, to help themselves and show the viewing audience that they can get good help, too. So, what about showing the private lives of therapists? With that, too, I can see the positives and negatives.

Because there is a power differential between a therapist and a client, the client can sometimes idealize the therapist, despite the fact that the client consciously understands the therapist is a real person, with faults and all like everybody else. Unconsciously, however, the power differential can cause the client to see the therapist as perfectly well balanced, and that's never true. In this way, showing the real-life side of the therapist can be a positive. But we're talking about reality TV here, so we must discuss the possibility that the therapists might end up looking a little unprofessional or, worse, insane in the membrane. (Remember that song from the 90s?)

The greatest possible danger in showcasing the lives of therapists is that the focus on the therapist takes the focus away from the client. It's hard to say where the future reputation of psychotherapy is headed given its new incarnations (reality TV, telemedicine, and even online therapy), but talking about it as a professional community is important. After all, we need to practice what we preach to our clients: It's all about insight and understanding the motivations.

Q. It can be gauged from the passage that the author of the passage has the following feelings towards L.A. Shrinks, the new show on BRAVO:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Let's be honest: The change has been coming for a while. Reality television has inserted itself into the field of psychology as countless shows over the years have begun to use psychotherapists as a part of their cast. Therapy has long been a subject of at least mild intrigue because what is said to the therapist behind closed doors - well, one never really knows unless you're either the client or the therapist. For the most part, the psychotherapy room has historically acted as a sacred chamber, the rare place where the client feels safe and listened to, and the therapist acts as the supportive mirror, guide, and confidant.

The first reality show I ever saw which a therapist, Breaking Bonaduce (2005), had focused on the life of former TV star Danny Bonaduce. I remember thinking at the time how unusual it was that a therapist was actually having a session with clients - drumroll...and cameras! - in the same room. Back then, I didn't think too much of it, probably dismissing psychotherapy on TV as a passing fad. (It is worth mentioning, however, that the therapy I saw conducted on the show was actually pretty good.) Over the years, we have seen more therapists in reality television and audiences have sat through excerpts of more therapy sessions than I can - or want to - count. As the medium of TV therapy has become more common - heck, even expected on your average reality show - it's caused me to reflect on 1) what possesses the clients to be interested in venting their problems in such a public way, and 2) what possesses the therapists to want to show the therapy with their clients on TV. When it comes to the clients' motivations, I have heard many people say, "Oh, they just want attention." First, I'm not sure it's that simple.

I give psychotherapy clients an awful lot of credit for having the strength and courage to work on their issues, and I see it as my job as a therapist to protect them and their (often potentially) vulnerable feelings. Even if a client of mine said he wanted to appear on television in a therapy session, I'd have to really think about whether it would be good for him or her. Perhaps for some it would be okay, while it would be problematic for others? My sense, although no one can say for sure, is that it is probably ideal for a client to discuss their issues with the world later, once they're out of the woods and can look back on a hard time with the solace of knowing they're stronger now. Nevertheless, I've worked with clients on talk shows (e.g., The Doctors) where cameras documented their issues (e.g., problems with road rage) as well as my interventions to help them. In some ways, that's not so different from reality TV therapy, right?

Which brings us to L.A. Shrinks, the new show on BRAVO. The show, instead of focusing exclusively on the lives of the clients, also focuses on three therapists and - wait for it - their private lives! The show gives the audience a backstage pass into the personal lives of the therapists, and includes footage of emotional and dramatic moments for each of the therapists. Quite honestly, this show takes psychotherapists on television to another level. Incidentally, casting people for the show contacted me a while ago and asked me if I would be interested in trying out for the show. I said "no" because the idea of the show confused me: Would it bring the usual magic of reality TV, replete with crafted editing that makes the therapists look nuts? Would my clients end up feeling exploited? I felt instantly protective of the profession of psychology and psychotherapy, as well as the clients who seek it out.

The truth is that good therapy is one of the most wonderful and life-changing experiences a person can have, and I hate to think that therapy will ultimately seem like a dog-and-pony show that's full of emotional fireworks or, God forbid, turning over tables, which occurred on a Real Housewives of New Jersey episode on the same network. Simply put, the show worries me for fear of the reputation of psychotherapy. I can see both positives and negatives to showing excerpts of therapy sessions, provided that the client and therapist and doing it for the right reasons: plain and simple, to help themselves and show the viewing audience that they can get good help, too. So, what about showing the private lives of therapists? With that, too, I can see the positives and negatives.

Because there is a power differential between a therapist and a client, the client can sometimes idealize the therapist, despite the fact that the client consciously understands the therapist is a real person, with faults and all like everybody else. Unconsciously, however, the power differential can cause the client to see the therapist as perfectly well balanced, and that's never true. In this way, showing the real-life side of the therapist can be a positive. But we're talking about reality TV here, so we must discuss the possibility that the therapists might end up looking a little unprofessional or, worse, insane in the membrane. (Remember that song from the 90s?)

The greatest possible danger in showcasing the lives of therapists is that the focus on the therapist takes the focus away from the client. It's hard to say where the future reputation of psychotherapy is headed given its new incarnations (reality TV, telemedicine, and even online therapy), but talking about it as a professional community is important. After all, we need to practice what we preach to our clients: It's all about insight and understanding the motivations.

Q. According to the author, a positive of showing therapy on television is:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Let's be honest: The change has been coming for a while. Reality television has inserted itself into the field of psychology as countless shows over the years have begun to use psychotherapists as a part of their cast. Therapy has long been a subject of at least mild intrigue because what is said to the therapist behind closed doors - well, one never really knows unless you're either the client or the therapist. For the most part, the psychotherapy room has historically acted as a sacred chamber, the rare place where the client feels safe and listened to, and the therapist acts as the supportive mirror, guide, and confidant.

The first reality show I ever saw which a therapist, Breaking Bonaduce (2005), had focused on the life of former TV star Danny Bonaduce. I remember thinking at the time how unusual it was that a therapist was actually having a session with clients - drumroll...and cameras! - in the same room. Back then, I didn't think too much of it, probably dismissing psychotherapy on TV as a passing fad. (It is worth mentioning, however, that the therapy I saw conducted on the show was actually pretty good.) Over the years, we have seen more therapists in reality television and audiences have sat through excerpts of more therapy sessions than I can - or want to - count. As the medium of TV therapy has become more common - heck, even expected on your average reality show - it's caused me to reflect on 1) what possesses the clients to be interested in venting their problems in such a public way, and 2) what possesses the therapists to want to show the therapy with their clients on TV. When it comes to the clients' motivations, I have heard many people say, "Oh, they just want attention." First, I'm not sure it's that simple.

I give psychotherapy clients an awful lot of credit for having the strength and courage to work on their issues, and I see it as my job as a therapist to protect them and their (often potentially) vulnerable feelings. Even if a client of mine said he wanted to appear on television in a therapy session, I'd have to really think about whether it would be good for him or her. Perhaps for some it would be okay, while it would be problematic for others? My sense, although no one can say for sure, is that it is probably ideal for a client to discuss their issues with the world later, once they're out of the woods and can look back on a hard time with the solace of knowing they're stronger now. Nevertheless, I've worked with clients on talk shows (e.g., The Doctors) where cameras documented their issues (e.g., problems with road rage) as well as my interventions to help them. In some ways, that's not so different from reality TV therapy, right?

Which brings us to L.A. Shrinks, the new show on BRAVO. The show, instead of focusing exclusively on the lives of the clients, also focuses on three therapists and - wait for it - their private lives! The show gives the audience a backstage pass into the personal lives of the therapists, and includes footage of emotional and dramatic moments for each of the therapists. Quite honestly, this show takes psychotherapists on television to another level. Incidentally, casting people for the show contacted me a while ago and asked me if I would be interested in trying out for the show. I said "no" because the idea of the show confused me: Would it bring the usual magic of reality TV, replete with crafted editing that makes the therapists look nuts? Would my clients end up feeling exploited? I felt instantly protective of the profession of psychology and psychotherapy, as well as the clients who seek it out.

The truth is that good therapy is one of the most wonderful and life-changing experiences a person can have, and I hate to think that therapy will ultimately seem like a dog-and-pony show that's full of emotional fireworks or, God forbid, turning over tables, which occurred on a Real Housewives of New Jersey episode on the same network. Simply put, the show worries me for fear of the reputation of psychotherapy. I can see both positives and negatives to showing excerpts of therapy sessions, provided that the client and therapist and doing it for the right reasons: plain and simple, to help themselves and show the viewing audience that they can get good help, too. So, what about showing the private lives of therapists? With that, too, I can see the positives and negatives.

Because there is a power differential between a therapist and a client, the client can sometimes idealize the therapist, despite the fact that the client consciously understands the therapist is a real person, with faults and all like everybody else. Unconsciously, however, the power differential can cause the client to see the therapist as perfectly well balanced, and that's never true. In this way, showing the real-life side of the therapist can be a positive. But we're talking about reality TV here, so we must discuss the possibility that the therapists might end up looking a little unprofessional or, worse, insane in the membrane. (Remember that song from the 90s?)

The greatest possible danger in showcasing the lives of therapists is that the focus on the therapist takes the focus away from the client. It's hard to say where the future reputation of psychotherapy is headed given its new incarnations (reality TV, telemedicine, and even online therapy), but talking about it as a professional community is important. After all, we need to practice what we preach to our clients: It's all about insight and understanding the motivations.

According to the author of the passage, which of the following are true about therapy?

I. Therapy has the power to alter the life of an individual.

II. Clients, without being aware of it, can begin to view the therapist as someone without any issues of his own.

III. Therapy, over the years, has gained more prominence on TV.

IV. To begin with, the author did not think therapy would last on TV.

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Last Thursday Starbucks raised their beverage prices by an average of 1% across the U.S, a move that represented the company's first significant price increase in 18 months. I failed to notice because the price change didn't affect grande or venti (medium and large) brewed coffees and I don't mess with smaller sizes, but anyone who purchases tall size (small) brews saw as much as a 10 cent increase. The company's third-quarter net income rose 25% to $417.8 million from $333.1 million a year earlier, and green coffee prices have plummeted, so what gives?

Starbucks claims the price increase is due to rising labor and non-coffee commodity costs, but with the significantly lower coffee costs already improving their profit margins, it seems unlikely this justification is the true reason for the hike in prices. In addition, the price hike was applied to less than a third of their beverages and only targets certain regions. Implementing such a specific and minor price increase when the bottom line is already in great shape might seem like a greedy tactic, but the Starbucks approach to pricing is one we can all use to improve our margins. As we've said before, it only takes a 1% increase in prices to raise profits by an average of 11%.

For the most part, Starbucks is a master of employing value-based pricing to maximize profits, and they use research and customer analysis to formulate targeted price increases that capture the greatest amount consumers are willing to pay without driving them off. Profit maximization is the process by which a company determines the price and product output level that generates the most profit. While that may seem obvious to anyone involved in running a business, it's rare to see companies using a value-based pricing approach to effectively uncover the maximum amount a customer base is willing to spend on their products. As such, let's take a look at how Starbucks introduces price hikes and see how you can use their approach to generate higher profits. While cutting prices is widely accepted as the best way to keep customers during tough times, the practice is rarely based on a deeper analysis or testing of an actual customer base. In Starbucks' case, price increases throughout the company's history have already deterred the most price-sensitive customers, leaving a loyal, higher-income consumer base that perceives these coffee beverages as an affordable luxury. In order to compensate for the customers lost to cheaper alternatives like Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks raises prices to maximize profits from these price-insensitive customers who now depend on their strong gourmet coffee.

Rather than trying to compete with cheaper chains like Dunkin, Starbucks uses price hikes to separate itself from the pack and reinforce the premium image of their brand and products. Since their loyal following isn't especially price-sensitive, Starbucks coffee maintains a fairly inelastic demand curve, and a small price increase can have a huge positive impact on their margins without decreasing demand for beverages. In addition, only certain regions are targeted for each price increase, and prices vary across the U.S. depending on the current markets in those areas (the most recent hike affects the Northeast and Sunbelt regions, but Florida and California prices remain the same).

They also apply price increases to specific drinks and sizes rather than the whole lot. By raising the price of the tall size brewed coffee exclusively, Starbucks is able to capture consumer surplus from the customers who find more value in upgrading to grande after witnessing the price of a small drip with tax climb over the $2 mark. By versioning the product in this way, the company can enjoy a slightly higher margin from these customers who were persuaded by the price hike to purchase larger sizes.

Starbucks also expertly communicates its price increases to manipulate consumer perception. The price hike might be based on an analysis of the customer's willingness to pay, but they associate the increase with what appears to be a fair reason. Using increased commodity costs to justify the price as well as statements that aim to make the hike look insignificant (less than a third of beverages will be affected, for example) help foster an attitude of acceptance.

The author of the passage is of the opinion that:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Last Thursday Starbucks raised their beverage prices by an average of 1% across the U.S, a move that represented the company's first significant price increase in 18 months. I failed to notice because the price change didn't affect grande or venti (medium and large) brewed coffees and I don't mess with smaller sizes, but anyone who purchases tall size (small) brews saw as much as a 10 cent increase. The company's third-quarter net income rose 25% to $417.8 million from $333.1 million a year earlier, and green coffee prices have plummeted, so what gives?

Starbucks claims the price increase is due to rising labor and non-coffee commodity costs, but with the significantly lower coffee costs already improving their profit margins, it seems unlikely this justification is the true reason for the hike in prices. In addition, the price hike was applied to less than a third of their beverages and only targets certain regions. Implementing such a specific and minor price increase when the bottom line is already in great shape might seem like a greedy tactic, but the Starbucks approach to pricing is one we can all use to improve our margins. As we've said before, it only takes a 1% increase in prices to raise profits by an average of 11%.

For the most part, Starbucks is a master of employing value-based pricing to maximize profits, and they use research and customer analysis to formulate targeted price increases that capture the greatest amount consumers are willing to pay without driving them off. Profit maximization is the process by which a company determines the price and product output level that generates the most profit. While that may seem obvious to anyone involved in running a business, it's rare to see companies using a value-based pricing approach to effectively uncover the maximum amount a customer base is willing to spend on their products. As such, let's take a look at how Starbucks introduces price hikes and see how you can use their approach to generate higher profits. While cutting prices is widely accepted as the best way to keep customers during tough times, the practice is rarely based on a deeper analysis or testing of an actual customer base. In Starbucks' case, price increases throughout the company's history have already deterred the most price-sensitive customers, leaving a loyal, higher-income consumer base that perceives these coffee beverages as an affordable luxury. In order to compensate for the customers lost to cheaper alternatives like Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks raises prices to maximize profits from these price-insensitive customers who now depend on their strong gourmet coffee.

Rather than trying to compete with cheaper chains like Dunkin, Starbucks uses price hikes to separate itself from the pack and reinforce the premium image of their brand and products. Since their loyal following isn't especially price-sensitive, Starbucks coffee maintains a fairly inelastic demand curve, and a small price increase can have a huge positive impact on their margins without decreasing demand for beverages. In addition, only certain regions are targeted for each price increase, and prices vary across the U.S. depending on the current markets in those areas (the most recent hike affects the Northeast and Sunbelt regions, but Florida and California prices remain the same).

They also apply price increases to specific drinks and sizes rather than the whole lot. By raising the price of the tall size brewed coffee exclusively, Starbucks is able to capture consumer surplus from the customers who find more value in upgrading to grande after witnessing the price of a small drip with tax climb over the $2 mark. By versioning the product in this way, the company can enjoy a slightly higher margin from these customers who were persuaded by the price hike to purchase larger sizes.

Starbucks also expertly communicates its price increases to manipulate consumer perception. The price hike might be based on an analysis of the customer's willingness to pay, but they associate the increase with what appears to be a fair reason. Using increased commodity costs to justify the price as well as statements that aim to make the hike look insignificant (less than a third of beverages will be affected, for example) help foster an attitude of acceptance.

As stated in the passage, an effective way to increase prices would include:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given at the end.

Last Thursday Starbucks raised their beverage prices by an average of 1% across the U.S, a move that represented the company's first significant price increase in 18 months. I failed to notice because the price change didn't affect grande or venti (medium and large) brewed coffees and I don't mess with smaller sizes, but anyone who purchases tall size (small) brews saw as much as a 10 cent increase. The company's third-quarter net income rose 25% to $417.8 million from $333.1 million a year earlier, and green coffee prices have plummeted, so what gives?

Starbucks claims the price increase is due to rising labor and non-coffee commodity costs, but with the significantly lower coffee costs already improving their profit margins, it seems unlikely this justification is the true reason for the hike in prices. In addition, the price hike was applied to less than a third of their beverages and only targets certain regions. Implementing such a specific and minor price increase when the bottom line is already in great shape might seem like a greedy tactic, but the Starbucks approach to pricing is one we can all use to improve our margins. As we've said before, it only takes a 1% increase in prices to raise profits by an average of 11%.

For the most part, Starbucks is a master of employing value-based pricing to maximize profits, and they use research and customer analysis to formulate targeted price increases that capture the greatest amount consumers are willing to pay without driving them off. Profit maximization is the process by which a company determines the price and product output level that generates the most profit. While that may seem obvious to anyone involved in running a business, it's rare to see companies using a value-based pricing approach to effectively uncover the maximum amount a customer base is willing to spend on their products. As such, let's take a look at how Starbucks introduces price hikes and see how you can use their approach to generate higher profits. While cutting prices is widely accepted as the best way to keep customers during tough times, the practice is rarely based on a deeper analysis or testing of an actual customer base. In Starbucks' case, price increases throughout the company's history have already deterred the most price-sensitive customers, leaving a loyal, higher-income consumer base that perceives these coffee beverages as an affordable luxury. In order to compensate for the customers lost to cheaper alternatives like Dunkin Donuts, Starbucks raises prices to maximize profits from these price-insensitive customers who now depend on their strong gourmet coffee.

Rather than trying to compete with cheaper chains like Dunkin, Starbucks uses price hikes to separate itself from the pack and reinforce the premium image of their brand and products. Since their loyal following isn't especially price-sensitive, Starbucks coffee maintains a fairly inelastic demand curve, and a small price increase can have a huge positive impact on their margins without decreasing demand for beverages. In addition, only certain regions are targeted for each price increase, and prices vary across the U.S. depending on the current markets in those areas (the most recent hike affects the Northeast and Sunbelt regions, but Florida and California prices remain the same).

They also apply price increases to specific drinks and sizes rather than the whole lot. By raising the price of the tall size brewed coffee exclusively, Starbucks is able to capture consumer surplus from the customers who find more value in upgrading to grande after witnessing the price of a small drip with tax climb over the $2 mark. By versioning the product in this way, the company can enjoy a slightly higher margin from these customers who were persuaded by the price hike to purchase larger sizes.

Starbucks also expertly communicates its price increases to manipulate consumer perception. The price hike might be based on an analysis of the customer's willingness to pay, but they associate the increase with what appears to be a fair reason. Using increased commodity costs to justify the price as well as statements that aim to make the hike look insignificant (less than a third of beverages will be affected, for example) help foster an attitude of acceptance.

As stated in the passage, the primary backbone of Starbucks' business strategy for profit maximization is: