IIFT Mock Test - 5 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 5 (New Pattern)

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage.

As someone' said, this crisis was too valuable to waste. I, for one, learnt many lessons on crisis management and leadership. By far the most important lesson I learnt is that the primary focus of a central bank during a crisis has to be on restoring confidence in the markets, and what this requires is swift, bold and decisive action. This is not as obvious'as it sounds because central banks are typically given to agonizing over every move they make out of anxiety that failure of their actions to deliver the intended impact will hurt their creditability and their policy effectiveness down the line. There is a lot to be said for such deliberative action in normal times: In crisis times though, it is important for them to take more chances without being too mindful of whether all of their actions are going to be fully effective or even mildly successful. After all, crisis management is a percentage game, and you do what you think has the best chance of reversing the momentum. Often, it is a fact of the action rather than the precise nature of the action that bolsters confidence. Take the Reserve Bank's measure I wrote about earlier of instituting exclusive lines of credit for augmenting the liquidity of NBFCs and mutual funds (MFs) which came under redemption pressure. It is simply unthinkable that the Reserve Bank would have done anything like this in normal times. In the event of a liquidity constraint in normal times, the standard response of the Reserve Bank would be to ease liquidity in the overall system an_d leave it to the banks to determine how to use that additional liquidity.

But here, we were targeting monetary policy at a particular class of financial institutions-the MFs &NBFCs-a; decidedly unconventional action. This departure from standard protocol pushed some of our senior staff beyond their comfort zones. Their reservations ranged from: 'this is not bowing monetary policy is done' to 'this will make the Reserve Bank vulnerable to pressures to bail out other sectors'. After hearing them out, I made the call to go ahead: Market participants applauded the new facility and saw it as the Reserve Bank's willingness to embrace unorthodox measures to address Specific areas of pressure in the system. In the event, these facilities were not significantly tapped: In normal times, that would have been seen as a failure of policy. From the crisis perspective though, it was a success in as much as the very existence of the central bank backstop restored confidence in the NBFCs and MFs and smoothed pressures in the financial system. Similarly, the cut in the repo rate of one full percentage point that I effected in October 2008 was a non-standard action from the perspective of a central bank used to cutting the interest rate by a maximum of half a percentage point (50 basis points in the jargon) when it wanted to signal strong action. Of course, we deliberated the advisability of going into uncharted waters and how it might set expectations. For the future. For example, in the future, the market may discount a 50 basis-point cut as too tame. But considering the uncertain and unpredictable global environment and the imperative to improve the flow of credit in a stressed situation, I bit the bullet again and decided on a full percentage-point cut.

Managing the tension between short-term payoffs and longer-term consequences is a constant struggle in all central bank policy choices as indeed it is in all public policy decisions. This balance between horizons shifts in crisis times, as dousing the fires becomes an overriding priority even if some of the actions taken to do that may have·some longer-term costs. For example, in 2008, we saw a massive infusion of liquidity as the best bet for preserving the financial stability of our markets. Indeed, d in uncharted waters, erring on the side of caution meant providing the system with more liquidity than considered adequate. This strategy was effective in the short-term, but with hindsight, we know that excess liquidity may have reinforced inflation pressures down the line. But remember, we were making a judgement call in real time. Analysts who are criticising us are doing so with the benefit of hindsight. Another lesson we learnt is that even in a global crisis, central banks have to adapt their responses to domestic conditions. I am saying this because of all through the crisis months. Whenever another central bank, especially an advanced economy central bank, announced any measure, there was an immediate pressure that the Reserve Bank too should institute a similar measure. Such straightforward copying of measures of other central banks without first examining their appropriateness for the domestic situation can often do more harm than good: Let me illustrate. During th depth of the crisis, fearing a run on their banks, the UK authorities bad extended deposit insurance across board to all deposits in the UK banking system. Immediately, there were commentators asking that the Reserve Bank too must embrace such an all-out measure. If we had actually done that, the results would have been counterproductive if not outright harmful. First, the available premium would not have been able to support such a blanket insurance, and the markets were aware of that.

If we had glossed over that and announced a blanket cover anyway, that action would have clearly lacked credibility. Besides, any such move would be at odds with what we had been asserting that our banks and our financial systems were safe and sound: The inconsistency between our walk and talk would have confused the markets; instead of reassuring them, any blanket insurance of the UK type·would have scared the public and sown seeds of doubt about the safety of their bank deposits, potentially triggering a run on some vulnerable banks. Finally, an important lesson from the crisis relates to the imperative of the government and the regulators speaking and acting in unison. It is possible to argue that public disclosure of differences within closed doors of policymaking could actually be helpful in enhancing public understanding on how policy might evolve in the future. For example, a 6-6 vote conveys a different message from a 12-0 vote. During crisis times, though, sending mixed signals to fragile markets can do huge damage. On the other hand, the demonstration of unity of purpose would reassure markets and yield great synergies. The experience of the crisis from around the world and our own experience too showed that coordination could be managed without compromising regulatory autonomy. Merely synchronizing policy announcements for exploiting the synergistic impact need not necessarily imply that regulators were being forced into actions they did not own.

Q. What 'crisis' is the author referring to, in the above passage?

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage.

As someone' said, this crisis was too valuable to waste. I, for one, learnt many lessons on crisis management and leadership. By far the most important lesson I learnt is that the primary focus of a central bank during a crisis has to be on restoring confidence in the markets, and what this requires is swift, bold and decisive action. This is not as obvious'as it sounds because central banks are typically given to agonizing over every move they make out of anxiety that failure of their actions to deliver the intended impact will hurt their creditability and their policy effectiveness down the line. There is a lot to be said for such deliberative action in normal times: In crisis times though, it is important for them to take more chances without being too mindful of whether all of their actions are going to be fully effective or even mildly successful. After all, crisis management is a percentage game, and you do what you think has the best chance of reversing the momentum. Often, it is a fact of the action rather than the precise nature of the action that bolsters confidence. Take the Reserve Bank's measure I wrote about earlier of instituting exclusive lines of credit for augmenting the liquidity of NBFCs and mutual funds (MFs) which came under redemption pressure. It is simply unthinkable that the Reserve Bank would have done anything like this in normal times. In the event of a liquidity constraint in normal times, the standard response of the Reserve Bank would be to ease liquidity in the overall system an_d leave it to the banks to determine how to use that additional liquidity.

But here, we were targeting monetary policy at a particular class of financial institutions-the MFs &NBFCs-a; decidedly unconventional action. This departure from standard protocol pushed some of our senior staff beyond their comfort zones. Their reservations ranged from: 'this is not bowing monetary policy is done' to 'this will make the Reserve Bank vulnerable to pressures to bail out other sectors'. After hearing them out, I made the call to go ahead: Market participants applauded the new facility and saw it as the Reserve Bank's willingness to embrace unorthodox measures to address Specific areas of pressure in the system. In the event, these facilities were not significantly tapped: In normal times, that would have been seen as a failure of policy. From the crisis perspective though, it was a success in as much as the very existence of the central bank backstop restored confidence in the NBFCs and MFs and smoothed pressures in the financial system. Similarly, the cut in the repo rate of one full percentage point that I effected in October 2008 was a non-standard action from the perspective of a central bank used to cutting the interest rate by a maximum of half a percentage point (50 basis points in the jargon) when it wanted to signal strong action. Of course, we deliberated the advisability of going into uncharted waters and how it might set expectations. For the future. For example, in the future, the market may discount a 50 basis-point cut as too tame. But considering the uncertain and unpredictable global environment and the imperative to improve the flow of credit in a stressed situation, I bit the bullet again and decided on a full percentage-point cut.

Managing the tension between short-term payoffs and longer-term consequences is a constant struggle in all central bank policy choices as indeed it is in all public policy decisions. This balance between horizons shifts in crisis times, as dousing the fires becomes an overriding priority even if some of the actions taken to do that may have·some longer-term costs. For example, in 2008, we saw a massive infusion of liquidity as the best bet for preserving the financial stability of our markets. Indeed, d in uncharted waters, erring on the side of caution meant providing the system with more liquidity than considered adequate. This strategy was effective in the short-term, but with hindsight, we know that excess liquidity may have reinforced inflation pressures down the line. But remember, we were making a judgement call in real time. Analysts who are criticising us are doing so with the benefit of hindsight. Another lesson we learnt is that even in a global crisis, central banks have to adapt their responses to domestic conditions. I am saying this because of all through the crisis months. Whenever another central bank, especially an advanced economy central bank, announced any measure, there was an immediate pressure that the Reserve Bank too should institute a similar measure. Such straightforward copying of measures of other central banks without first examining their appropriateness for the domestic situation can often do more harm than good: Let me illustrate. During th depth of the crisis, fearing a run on their banks, the UK authorities bad extended deposit insurance across board to all deposits in the UK banking system. Immediately, there were commentators asking that the Reserve Bank too must embrace such an all-out measure. If we had actually done that, the results would have been counterproductive if not outright harmful. First, the available premium would not have been able to support such a blanket insurance, and the markets were aware of that.

If we had glossed over that and announced a blanket cover anyway, that action would have clearly lacked credibility. Besides, any such move would be at odds with what we had been asserting that our banks and our financial systems were safe and sound: The inconsistency between our walk and talk would have confused the markets; instead of reassuring them, any blanket insurance of the UK type·would have scared the public and sown seeds of doubt about the safety of their bank deposits, potentially triggering a run on some vulnerable banks. Finally, an important lesson from the crisis relates to the imperative of the government and the regulators speaking and acting in unison. It is possible to argue that public disclosure of differences within closed doors of policymaking could actually be helpful in enhancing public understanding on how policy might evolve in the future. For example, a 6-6 vote conveys a different message from a 12-0 vote. During crisis times, though, sending mixed signals to fragile markets can do huge damage. On the other hand, the demonstration of unity of purpose would reassure markets and yield great synergies. The experience of the crisis from around the world and our own experience too showed that coordination could be managed without compromising regulatory autonomy. Merely synchronizing policy announcements for exploiting the synergistic impact need not necessarily imply that regulators were being forced into actions they did not own.

Q. With reference to theabove passage, what is the role of government and regulators in times of crisis? Select the most ppropriate response with reference to information provided in the passage.

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage.

As someone' said, this crisis was too valuable to waste. I, for one, learnt many lessons on crisis management and leadership. By far the most important lesson I learnt is that the primary focus of a central bank during a crisis has to be on restoring confidence in the markets, and what this requires is swift, bold and decisive action. This is not as obvious'as it sounds because central banks are typically given to agonizing over every move they make out of anxiety that failure of their actions to deliver the intended impact will hurt their creditability and their policy effectiveness down the line. There is a lot to be said for such deliberative action in normal times: In crisis times though, it is important for them to take more chances without being too mindful of whether all of their actions are going to be fully effective or even mildly successful. After all, crisis management is a percentage game, and you do what you think has the best chance of reversing the momentum. Often, it is a fact of the action rather than the precise nature of the action that bolsters confidence. Take the Reserve Bank's measure I wrote about earlier of instituting exclusive lines of credit for augmenting the liquidity of NBFCs and mutual funds (MFs) which came under redemption pressure. It is simply unthinkable that the Reserve Bank would have done anything like this in normal times. In the event of a liquidity constraint in normal times, the standard response of the Reserve Bank would be to ease liquidity in the overall system an_d leave it to the banks to determine how to use that additional liquidity.

But here, we were targeting monetary policy at a particular class of financial institutions-the MFs &NBFCs-a; decidedly unconventional action. This departure from standard protocol pushed some of our senior staff beyond their comfort zones. Their reservations ranged from: 'this is not bowing monetary policy is done' to 'this will make the Reserve Bank vulnerable to pressures to bail out other sectors'. After hearing them out, I made the call to go ahead: Market participants applauded the new facility and saw it as the Reserve Bank's willingness to embrace unorthodox measures to address Specific areas of pressure in the system. In the event, these facilities were not significantly tapped: In normal times, that would have been seen as a failure of policy. From the crisis perspective though, it was a success in as much as the very existence of the central bank backstop restored confidence in the NBFCs and MFs and smoothed pressures in the financial system. Similarly, the cut in the repo rate of one full percentage point that I effected in October 2008 was a non-standard action from the perspective of a central bank used to cutting the interest rate by a maximum of half a percentage point (50 basis points in the jargon) when it wanted to signal strong action. Of course, we deliberated the advisability of going into uncharted waters and how it might set expectations. For the future. For example, in the future, the market may discount a 50 basis-point cut as too tame. But considering the uncertain and unpredictable global environment and the imperative to improve the flow of credit in a stressed situation, I bit the bullet again and decided on a full percentage-point cut.

Managing the tension between short-term payoffs and longer-term consequences is a constant struggle in all central bank policy choices as indeed it is in all public policy decisions. This balance between horizons shifts in crisis times, as dousing the fires becomes an overriding priority even if some of the actions taken to do that may have·some longer-term costs. For example, in 2008, we saw a massive infusion of liquidity as the best bet for preserving the financial stability of our markets. Indeed, d in uncharted waters, erring on the side of caution meant providing the system with more liquidity than considered adequate. This strategy was effective in the short-term, but with hindsight, we know that excess liquidity may have reinforced inflation pressures down the line. But remember, we were making a judgement call in real time. Analysts who are criticising us are doing so with the benefit of hindsight. Another lesson we learnt is that even in a global crisis, central banks have to adapt their responses to domestic conditions. I am saying this because of all through the crisis months. Whenever another central bank, especially an advanced economy central bank, announced any measure, there was an immediate pressure that the Reserve Bank too should institute a similar measure. Such straightforward copying of measures of other central banks without first examining their appropriateness for the domestic situation can often do more harm than good: Let me illustrate. During th depth of the crisis, fearing a run on their banks, the UK authorities bad extended deposit insurance across board to all deposits in the UK banking system. Immediately, there were commentators asking that the Reserve Bank too must embrace such an all-out measure. If we had actually done that, the results would have been counterproductive if not outright harmful. First, the available premium would not have been able to support such a blanket insurance, and the markets were aware of that.

If we had glossed over that and announced a blanket cover anyway, that action would have clearly lacked credibility. Besides, any such move would be at odds with what we had been asserting that our banks and our financial systems were safe and sound: The inconsistency between our walk and talk would have confused the markets; instead of reassuring them, any blanket insurance of the UK type·would have scared the public and sown seeds of doubt about the safety of their bank deposits, potentially triggering a run on some vulnerable banks. Finally, an important lesson from the crisis relates to the imperative of the government and the regulators speaking and acting in unison. It is possible to argue that public disclosure of differences within closed doors of policymaking could actually be helpful in enhancing public understanding on how policy might evolve in the future. For example, a 6-6 vote conveys a different message from a 12-0 vote. During crisis times, though, sending mixed signals to fragile markets can do huge damage. On the other hand, the demonstration of unity of purpose would reassure markets and yield great synergies. The experience of the crisis from around the world and our own experience too showed that coordination could be managed without compromising regulatory autonomy. Merely synchronizing policy announcements for exploiting the synergistic impact need not necessarily imply that regulators were being forced into actions they did not own.

Q. According to the author, what is the typical response of central banks in times of crisis? Answer with reference to the passage.

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage.

As someone' said, this crisis was too valuable to waste. I, for one, learnt many lessons on crisis management and leadership. By far the most important lesson I learnt is that the primary focus of a central bank during a crisis has to be on restoring confidence in the markets, and what this requires is swift, bold and decisive action. This is not as obvious'as it sounds because central banks are typically given to agonizing over every move they make out of anxiety that failure of their actions to deliver the intended impact will hurt their creditability and their policy effectiveness down the line. There is a lot to be said for such deliberative action in normal times: In crisis times though, it is important for them to take more chances without being too mindful of whether all of their actions are going to be fully effective or even mildly successful. After all, crisis management is a percentage game, and you do what you think has the best chance of reversing the momentum. Often, it is a fact of the action rather than the precise nature of the action that bolsters confidence. Take the Reserve Bank's measure I wrote about earlier of instituting exclusive lines of credit for augmenting the liquidity of NBFCs and mutual funds (MFs) which came under redemption pressure. It is simply unthinkable that the Reserve Bank would have done anything like this in normal times. In the event of a liquidity constraint in normal times, the standard response of the Reserve Bank would be to ease liquidity in the overall system an_d leave it to the banks to determine how to use that additional liquidity.

But here, we were targeting monetary policy at a particular class of financial institutions-the MFs &NBFCs-a; decidedly unconventional action. This departure from standard protocol pushed some of our senior staff beyond their comfort zones. Their reservations ranged from: 'this is not bowing monetary policy is done' to 'this will make the Reserve Bank vulnerable to pressures to bail out other sectors'. After hearing them out, I made the call to go ahead: Market participants applauded the new facility and saw it as the Reserve Bank's willingness to embrace unorthodox measures to address Specific areas of pressure in the system. In the event, these facilities were not significantly tapped: In normal times, that would have been seen as a failure of policy. From the crisis perspective though, it was a success in as much as the very existence of the central bank backstop restored confidence in the NBFCs and MFs and smoothed pressures in the financial system. Similarly, the cut in the repo rate of one full percentage point that I effected in October 2008 was a non-standard action from the perspective of a central bank used to cutting the interest rate by a maximum of half a percentage point (50 basis points in the jargon) when it wanted to signal strong action. Of course, we deliberated the advisability of going into uncharted waters and how it might set expectations. For the future. For example, in the future, the market may discount a 50 basis-point cut as too tame. But considering the uncertain and unpredictable global environment and the imperative to improve the flow of credit in a stressed situation, I bit the bullet again and decided on a full percentage-point cut.

Managing the tension between short-term payoffs and longer-term consequences is a constant struggle in all central bank policy choices as indeed it is in all public policy decisions. This balance between horizons shifts in crisis times, as dousing the fires becomes an overriding priority even if some of the actions taken to do that may have·some longer-term costs. For example, in 2008, we saw a massive infusion of liquidity as the best bet for preserving the financial stability of our markets. Indeed, d in uncharted waters, erring on the side of caution meant providing the system with more liquidity than considered adequate. This strategy was effective in the short-term, but with hindsight, we know that excess liquidity may have reinforced inflation pressures down the line. But remember, we were making a judgement call in real time. Analysts who are criticising us are doing so with the benefit of hindsight. Another lesson we learnt is that even in a global crisis, central banks have to adapt their responses to domestic conditions. I am saying this because of all through the crisis months. Whenever another central bank, especially an advanced economy central bank, announced any measure, there was an immediate pressure that the Reserve Bank too should institute a similar measure. Such straightforward copying of measures of other central banks without first examining their appropriateness for the domestic situation can often do more harm than good: Let me illustrate. During th depth of the crisis, fearing a run on their banks, the UK authorities bad extended deposit insurance across board to all deposits in the UK banking system. Immediately, there were commentators asking that the Reserve Bank too must embrace such an all-out measure. If we had actually done that, the results would have been counterproductive if not outright harmful. First, the available premium would not have been able to support such a blanket insurance, and the markets were aware of that.

If we had glossed over that and announced a blanket cover anyway, that action would have clearly lacked credibility. Besides, any such move would be at odds with what we had been asserting that our banks and our financial systems were safe and sound: The inconsistency between our walk and talk would have confused the markets; instead of reassuring them, any blanket insurance of the UK type·would have scared the public and sown seeds of doubt about the safety of their bank deposits, potentially triggering a run on some vulnerable banks. Finally, an important lesson from the crisis relates to the imperative of the government and the regulators speaking and acting in unison. It is possible to argue that public disclosure of differences within closed doors of policymaking could actually be helpful in enhancing public understanding on how policy might evolve in the future. For example, a 6-6 vote conveys a different message from a 12-0 vote. During crisis times, though, sending mixed signals to fragile markets can do huge damage. On the other hand, the demonstration of unity of purpose would reassure markets and yield great synergies. The experience of the crisis from around the world and our own experience too showed that coordination could be managed without compromising regulatory autonomy. Merely synchronizing policy announcements for exploiting the synergistic impact need not necessarily imply that regulators were being forced into actions they did not own.

Q. Why does the author say ".. .even in a global crisis, central banks have to adapt their responses to domestic conditions"? Answer with reference to passage.

Directions: In each of the following questions, a part/two of a sentence has been left blank. You are to select from among the options given below each question, the one which would best fill the blanks. In case of more than one blanks, the first word in the pair, given in the choices, should fill the first gap.

Q. Football evokes a__________ response in India compared to cricket, that almost ________ the nation.

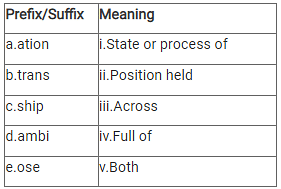

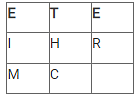

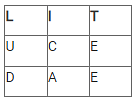

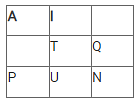

Create a word using all the given letters from the jumbled letters and identify its appropriate meaning.

Directions: Read the sentences below carefully and identify the nature of phrase/clause used in the underlined section of the sentences.

Q. Since you have already decided, why do you ask my opinion?

In which set each word is a noun, adjective and verb also:

Directions: Passage below is accompanied by a number of questions.

For some questions, consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage or punctuation.

After reading the passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage confirm to the conventions of standard written English.

The underlined areas in the passage along with the [number] direct you to the question concerned

If you've ever been to an art museum, you know the basic layout: long hallways and large rooms with paintings hung a few feet apart You know how the paintings are [1] by certain means are marked and you know that the paintings have been arranged chronologically or thematically.

There’s one thing, however, which you’ve definitely noticed even if you can’t quite articulate it- Particularly when looking at old paintings. [2] paintings all have that vividly new look, Whether they were painted in 1950 or 1450. Even where the subject matter is older, the colors are vibrant, and you're never forced to wonder exactly what the painting must have looked like in its original state.

[3] The history of painting is nearly as long as the history of mankind. The incredible feat is the work of a highly specialized group: art restorers. Despite this specialization, the profession has exploded in recent years. Art restoration has been growing steadily since 1930. While the job of an art restorer may seem fairly straight forward [4] When looking, the job is in fact quite complicated: Sometimes, as in the case of Michelangelo's famous sculpture David, the cleaning and restoration of art works is a simple matter: applying chemicals, washing away grime and scrubbing of the dirt.

[5] With most paintings however, the process is a good deal more involved because it is not necessarily, just a matter of 'cleaning' the older paintings. One cannot merely take a scrub brush to centuries - old great work, Because of the wide range of restoration techniques, art restoration itself can be controversial business.

Q. Identify the best possible change in the underlined area [5]?

Directions: Passage below is accompanied by a number of questions.

For some questions, consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage or punctuation.

Alter reading the passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage confirm to the conventions of standard written English.

The underlined areas in the passage along with the [number] direct you to the question concerned

If you've ever been to an art museum, you know the basic layout: long hallways and large rooms with paintings hung a few feet apart You know how the paintings are [1] by certain means are marked and you know that the paintings have been arranged chronologically or thematically.

There’s one thing, however, which you’ve definitely noticed even if you can’t quite articulate it- Particularly when looking at old paintings. [2] paintings all have that vividly new look, Whether they were painted in 1950 or 1450. Even where the subject matter is older, the colors are vibrant, and you're never forced to wonder exactly what the painting must have looked like in its original state.

[3] The history of painting is nearly as long as the history of mankind. The incredible feat is the work of a highly specialized group: art restorers. Despite this specialization, the profession has exploded in recent years. Art restoration has been growing steadily since 1930. While the job of an art restorer may seem fairly straight forward [4] When looking, the job is in fact quite complicated: Sometimes, as in the case of Michelangelo's famous sculpture David, the cleaning and restoration of art works is a simple matter: applying chemicals, washing away grime and scrubbing of the dirt.

[5] With most paintings however, the process is a good deal more involved because it is not necessarily, just a matter of 'cleaning' the older paintings. One cannot merely take a scrub brush to centuries-old great work, Because of the wide range of restoration techniques, art restoration itself can be controversial business.

Q. Identify the best possible change in the underlined area [2]?

Directions: Passage below is accompanied by a number of questions.

For some questions, consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage or punctuation.

Alter reading the passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage confirm to the conventions of standard written English.

The underlined areas in the passage along with the [number] direct you to the question concerned

If you've ever been to an art museum, you know the basic layout: long hallways and large rooms with paintings hung a few feet apart You know how the paintings are [1] by certain means are marked and you know that the paintings have been arranged chronologically or thematically.

There’s one thing, however, which you’ve definitely noticed even if you can’t quite articulate it- Particularly when looking at old paintings. [2] paintings all have that vividly new look, Whether they were painted in 1950 or 1450. Even where the subject matter is older, the colors are vibrant, and you're never forced to wonder exactly what the painting must have looked like in its original state.

[3] The history of painting is nearly as long as the history of mankind. The incredible feat is the work of a highly specialized group: art restorers. Despite this specialization, the profession has exploded in recent years. Art restoration has been growing steadily since 1930. While the job of an art restorer may seem fairly straight forward [4] When looking, the job is in fact quite complicated: Sometimes, as in the case of Michelangelo's famous sculpture David, the cleaning and restoration of art works is a simple matter: applying chemicals, washing away grime and scrubbing of the dirt.

[5] With most paintings however, the process is a good deal more involved because it is not necessarily, just a matter of 'cleaning' the older paintings. One cannot merely take a scrub brush to centuries-old great work, Because of the wide range of restoration techniques, art restoration itself can be controversial business.

Q. Identify the best possible change in the underlined area [1]?

Directions: Passage below is accompanied by a number of questions.

For some questions, consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage or punctuation.

Alter reading the passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage confirm to the conventions of standard written English.

The underlined areas in the passage along with the [number] direct you to the question concerned

If you've ever been to an art museum, you know the basic layout: long hallways and large rooms with paintings hung a few feet apart You know how the paintings are [1] by certain means are marked and you know that the paintings have been arranged chronologically or thematically.

There’s one thing, however, which you’ve definitely noticed even if you can’t quite articulate it- Particularly when looking at old paintings. [2] paintings all have that vividly new look, Whether they were painted in 1950 or 1450. Even where the subject matter is older, the colors are vibrant, and you're never forced to wonder exactly what the painting must have looked like in its original state.

[3] The history of painting is nearly as long as the history of mankind. The incredible feat is the work of a highly specialized group: art restorers. Despite this specialization, the profession has exploded in recent years. Art restoration has been growing steadily since 1930. While the job of an art restorer may seem fairly straight forward [4] When looking, the job is in fact quite complicated: Sometimes, as in the case of Michelangelo's famous sculpture David, the cleaning and restoration of art works is a simple matter: applying chemicals, washing away grime and scrubbing of the dirt.

[5] With most paintings however, the process is a good deal more involved because it is not necessarily, just a matter of 'cleaning' the older paintings. One cannot merely take a scrub brush to centuries-old great work, Because of the wide range of restoration techniques, art restoration itself can be controversial business.

Q. Identify the best possible change in the underlined area [4] ?

Directions: Passage below is accompanied by a number of questions.

For some questions, consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage or punctuation.

Alter reading the passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage confirm to the conventions of standard written English.

The underlined areas in the passage along with the [number] direct you to the question concerned

If you've ever been to an art museum, you know the basic layout: long hallways and large rooms with paintings hung a few feet apart You know how the paintings are [1] by certain means are marked and you know that the paintings have been arranged chronologically or thematically.

There’s one thing, however, which you’ve definitely noticed even if you can’t quite articulate it- Particularly when looking at old paintings. [2] paintings all have that vividly new look, Whether they were painted in 1950 or 1450. Even where the subject matter is older, the colors are vibrant, and you're never forced to wonder exactly what the painting must have looked like in its original state.

[3] The history of painting is nearly as long as the history of mankind. The incredible feat is the work of a highly specialized group: art restorers. Despite this specialization, the profession has exploded in recent years. Art restoration has been growing steadily since 1930. While the job of an art restorer may seem fairly straight forward [4] When looking, the job is in fact quite complicated: Sometimes, as in the case of Michelangelo's famous sculpture David, the cleaning and restoration of art works is a simple matter: applying chemicals, washing away grime and scrubbing of the dirt.

[5] With most paintings however, the process is a good deal more involved because it is not necessarily, just a matter of 'cleaning' the older paintings. One cannot merely take a scrub brush to centuries-old great work, Because of the wide range of restoration techniques, art restoration itself can be controversial business.

Q. The writer is considering deleting the underlined sentence. Should the sentence be kept or deleted [3]?

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage:

I wear a variety of professional hats- university professor, literacy consultant to districts, author of several books related to comprehension. To keep myself honest (and humble); l spend a lot of time in classrooms watching kids and teachers at work. During the past decade, I've observed a transformation in the teaching of reading from an approved:h that measured readers' successful understanding of the text through lengthy packets of comprehension questions to one that requires students to think about their thinking, activating their "good reader" strategies. Close reading is a deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a· reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form. Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Essentially, close reading means reading to uncover layers of meaning that lead to deep comprehension. "Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole." Reread the definition of close reading closely-to extract .key concepts. You might identify these ideas: examining meaning thoroughly and analytically; directing attention to the text, central ideas, and supporting details; reflecting on meanings of individual words and sentences; and developing ideas over the course of the text. Notice that reader reflection is still integral to the process. But close reading goes beyond that: The best thinkers do monitor and assess their thinking, but in the context of processing the thinking of others (Paul & Elder, 2008).

When you close read, you observe facts and details about the text. You may focus on a particular passage, or on the text as a whole. Your aim may be notice all striking features of the text, including rhetorical features, structural elements and cultural references; or, your aim may be to notice only selected features of the text- for instance, oppositions and correspondences, or particular historical references. Either way, making these observations constitutes the first step in the process of close reading. The second step is interpreting your observations. What we're basically talking about here is inductive reasoning: moving from the observation of particular facts and details to a conclusion, or interpretation, based on those observations. And, as with inductive reasoning, close reading requires the careful gathering of data (your observations) and careful thinking about what these data add up to. The literary analysis involves examining these components, which still allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character's daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like "tome" instead of ''book"? In effect, you are putting the author's choices under a microscope. The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work. Close reading sometimes feels like over-analysing, but don worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you'll sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. It's our responsibility as educators to build students' capacity for independently comprehending a text through close reading. Teaching is about the transfer. The goal is for students is to take what they learn from the study of one text and apply it to the next text they read: How can we ensure that students both reap the requisite knowledge from each text they read and acquire skills to pursue the meaning of other texts independently? I suggest we coach students to ask themselves four basic questions as they reflect on a specific portion of any text, even the shortest: What is the author telling me here? Are there any hard or important words? What does the author want me to understand? How does the author play with language to add to meaning? If students take time to ask themselves these questions while reading and become skilful at answering them, there'll be less need for the teacher to doll the asking. For this to happen, we must develop students' capacity to observe and analyse. First things first: See whether students have noticed the details of a passage and can recount those details in their own words. Note that the challenge here isn't to be brief (as in a summary); it's to be accurate, precise, and clear.

The recent focus on finding evidence in a text has sent students (even in primary grades) scurrying back to their books to retrieve a quote that validates their opinion. But to paraphrase what that quote means in a student's own language, rather than the author's, is more difficult than you might think. Try it with any paragraph. Expressing the same meaning with different words often requires going back to that text a few times to get the details just right. Paraphrasing is pretty low on Bloom's continuum of lower- to higher-order thinking, yet many students stumble even b: here. This is the first stop along the journey to close reading. If students can't paraphrase the basic content of a passage, how can they dig for its deeper meaning? The second basic question about hard or important words encourages students to zoom in on precise meaning. When students are satisfied that they have a basic grasp of what the author is telling them, they're ready to move on to analysing the fine points of content. If students begin their analysis by asking themselves the third question- What does the author want me to understand in this passage?-they'II be on their way to malcing appropriate inferences determining what the author is trying to show without stating it directly.

We can also teach students to read carefully with the eye of a writer, which means helping them analyse craft. How a text is written is as important as the content itself in getting the author's· message across. Just as a movie director focuses the camera on a particular detail to get you to view the scene the way he or she wants you to, authors play with words to get you to see a text their way. Introducing students to some of the tricks authors use opens students' minds to an entirely new realm in close reading.

Q. In the above passage the author has used the term 'Rhetoric features'. What does it mean?

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage:

I wear a variety of professional hats- university professor, literacy consultant to districts, author of several books related to comprehension. To keep myself honest (and humble); l spend a lot of time in classrooms watching kids and teachers at work. During the past decade, I've observed a transformation in the teaching of reading from an approved:h that measured readers' successful understanding of the text through lengthy packets of comprehension questions to one that requires students to think about their thinking, activating their "good reader" strategies. Close reading is a deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a· reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form. Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Essentially, close reading means reading to uncover layers of meaning that lead to deep comprehension. "Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole." Reread the definition of close reading closely-to extract .key concepts. You might identify these ideas: examining meaning thoroughly and analytically; directing attention to the text, central ideas, and supporting details; reflecting on meanings of individual words and sentences; and developing ideas over the course of the text. Notice that reader reflection is still integral to the process. But close reading goes beyond that: The best thinkers do monitor and assess their thinking, but in the context of processing the thinking of others (Paul & Elder, 2008).

When you close read, you observe facts and details about the text. You may focus on a particular passage, or on the text as a whole. Your aim may be notice all striking features of the text, including rhetorical features, structural elements and cultural references; or, your aim may be to notice only selected features of the text- for instance, oppositions and correspondences, or particular historical references. Either way, making these observations constitutes the first step in the process of close reading. The second step is interpreting your observations. What we're basically talking about here is inductive reasoning: moving from the observation of particular facts and details to a conclusion, or interpretation, based on those observations. And, as with inductive reasoning, close reading requires the careful gathering of data (your observations) and careful thinking about what these data add up to. The literary analysis involves examining these components, which still allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character's daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like "tome" instead of ''book"? In effect, you are putting the author's choices under a microscope. The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work. Close reading sometimes feels like over-analysing, but don worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you'll sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. It's our responsibility as educators to build students' capacity for independently comprehending a text through close reading. Teaching is about the transfer. The goal is for students is to take what they learn from the study of one text and apply it to the next text they read: How can we ensure that students both reap the requisite knowledge from each text they read and acquire skills to pursue the meaning of other texts independently? I suggest we coach students to ask themselves four basic questions as they reflect on a specific portion of any text, even the shortest: What is the author telling me here? Are there any hard or important words? What does the author want me to understand? How does the author play with language to add to meaning? If students take time to ask themselves these questions while reading and become skilful at answering them, there'll be less need for the teacher to doll the asking. For this to happen, we must develop students' capacity to observe and analyse. First things first: See whether students have noticed the details of a passage and can recount those details in their own words. Note that the challenge here isn't to be brief (as in a summary); it's to be accurate, precise, and clear.

The recent focus on finding evidence in a text has sent students (even in primary grades) scurrying back to their books to retrieve a quote that validates their opinion. But to paraphrase what that quote means in a student's own language, rather than the author's, is more difficult than you might think. Try it with any paragraph. Expressing the same meaning with different words often requires going back to that text a few times to get the details just right. Paraphrasing is pretty low on Bloom's continuum of lower- to higher-order thinking, yet many students stumble even b: here. This is the first stop along the journey to close reading. If students can't paraphrase the basic content of a passage, how can they dig for its deeper meaning? The second basic question about hard or important words encourages students to zoom in on precise meaning. When students are satisfied that they have a basic grasp of what the author is telling them, they're ready to move on to analysing the fine points of content. If students begin their analysis by asking themselves the third question- What does the author want me to understand in this passage?-they'II be on their way to malcing appropriate inferences determining what the author is trying to show without stating it directly.

We can also teach students to read carefully with the eye of a writer, which means helping them analyse craft. How a text is written is as important as the content itself in getting the author's· message across. Just as a movie director focuses the camera on a particular detail to get you to view the scene the way he or she wants you to, authors play with words to get you to see a text their way. Introducing students to some of the tricks authors use opens students' minds to an entirely new realm in close reading.

Q. With reference to the above passage, what responsibility, according to the author, do educators have?

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage:

I wear a variety of professional hats- university professor, literacy consultant to districts, author of several books related to comprehension. To keep myself honest (and humble); l spend a lot of time in classrooms watching kids and teachers at work. During the past decade, I've observed a transformation in the teaching of reading from an approved:h that measured readers' successful understanding of the text through lengthy packets of comprehension questions to one that requires students to think about their thinking, activating their "good reader" strategies. Close reading is a deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a· reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form. Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Essentially, close reading means reading to uncover layers of meaning that lead to deep comprehension. "Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole." Reread the definition of close reading closely-to extract .key concepts. You might identify these ideas: examining meaning thoroughly and analytically; directing attention to the text, central ideas, and supporting details; reflecting on meanings of individual words and sentences; and developing ideas over the course of the text. Notice that reader reflection is still integral to the process. But close reading goes beyond that: The best thinkers do monitor and assess their thinking, but in the context of processing the thinking of others (Paul & Elder, 2008).

When you close read, you observe facts and details about the text. You may focus on a particular passage, or on the text as a whole. Your aim may be notice all striking features of the text, including rhetorical features, structural elements and cultural references; or, your aim may be to notice only selected features of the text- for instance, oppositions and correspondences, or particular historical references. Either way, making these observations constitutes the first step in the process of close reading. The second step is interpreting your observations. What we're basically talking about here is inductive reasoning: moving from the observation of particular facts and details to a conclusion, or interpretation, based on those observations. And, as with inductive reasoning, close reading requires the careful gathering of data (your observations) and careful thinking about what these data add up to. The literary analysis involves examining these components, which still allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character's daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like "tome" instead of ''book"? In effect, you are putting the author's choices under a microscope. The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work. Close reading sometimes feels like over-analysing, but don worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you'll sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. It's our responsibility as educators to build students' capacity for independently comprehending a text through close reading. Teaching is about the transfer. The goal is for students is to take what they learn from the study of one text and apply it to the next text they read: How can we ensure that students both reap the requisite knowledge from each text they read and acquire skills to pursue the meaning of other texts independently? I suggest we coach students to ask themselves four basic questions as they reflect on a specific portion of any text, even the shortest: What is the author telling me here? Are there any hard or important words? What does the author want me to understand? How does the author play with language to add to meaning? If students take time to ask themselves these questions while reading and become skilful at answering them, there'll be less need for the teacher to doll the asking. For this to happen, we must develop students' capacity to observe and analyse. First things first: See whether students have noticed the details of a passage and can recount those details in their own words. Note that the challenge here isn't to be brief (as in a summary); it's to be accurate, precise, and clear.

The recent focus on finding evidence in a text has sent students (even in primary grades) scurrying back to their books to retrieve a quote that validates their opinion. But to paraphrase what that quote means in a student's own language, rather than the author's, is more difficult than you might think. Try it with any paragraph. Expressing the same meaning with different words often requires going back to that text a few times to get the details just right. Paraphrasing is pretty low on Bloom's continuum of lower- to higher-order thinking, yet many students stumble even b: here. This is the first stop along the journey to close reading. If students can't paraphrase the basic content of a passage, how can they dig for its deeper meaning? The second basic question about hard or important words encourages students to zoom in on precise meaning. When students are satisfied that they have a basic grasp of what the author is telling them, they're ready to move on to analysing the fine points of content. If students begin their analysis by asking themselves the third question- What does the author want me to understand in this passage?-they'II be on their way to malcing appropriate inferences determining what the author is trying to show without stating it directly.

We can also teach students to read carefully with the eye of a writer, which means helping them analyse craft. How a text is written is as important as the content itself in getting the author's· message across. Just as a movie director focuses the camera on a particular detail to get you to view the scene the way he or she wants you to, authors play with words to get you to see a text their way. Introducing students to some of the tricks authors use opens students' minds to an entirely new realm in close reading.

Q. According to the author what is inductive reasoning with regard to Close Reading?

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage:

I wear a variety of professional hats- university professor, literacy consultant to districts, author of several books related to comprehension. To keep myself honest (and humble); l spend a lot of time in classrooms watching kids and teachers at work. During the past decade, I've observed a transformation in the teaching of reading from an approved:h that measured readers' successful understanding of the text through lengthy packets of comprehension questions to one that requires students to think about their thinking, activating their "good reader" strategies. Close reading is a deep analysis of how a literary text works; it is both a· reading process and something you include in a literary analysis paper, though in a refined form. Fiction writers and poets build texts out of many central components, including subject, form, and specific word choices. Essentially, close reading means reading to uncover layers of meaning that lead to deep comprehension. "Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole." Reread the definition of close reading closely-to extract .key concepts. You might identify these ideas: examining meaning thoroughly and analytically; directing attention to the text, central ideas, and supporting details; reflecting on meanings of individual words and sentences; and developing ideas over the course of the text. Notice that reader reflection is still integral to the process. But close reading goes beyond that: The best thinkers do monitor and assess their thinking, but in the context of processing the thinking of others (Paul & Elder, 2008).

When you close read, you observe facts and details about the text. You may focus on a particular passage, or on the text as a whole. Your aim may be notice all striking features of the text, including rhetorical features, structural elements and cultural references; or, your aim may be to notice only selected features of the text- for instance, oppositions and correspondences, or particular historical references. Either way, making these observations constitutes the first step in the process of close reading. The second step is interpreting your observations. What we're basically talking about here is inductive reasoning: moving from the observation of particular facts and details to a conclusion, or interpretation, based on those observations. And, as with inductive reasoning, close reading requires the careful gathering of data (your observations) and careful thinking about what these data add up to. The literary analysis involves examining these components, which still allows us to find in small parts of the text clues to help us understand the whole. For example, if an author writes a novel in the form of a personal journal about a character's daily life, but that journal reads like a series of lab reports, what do we learn about that character? What is the effect of picking a word like "tome" instead of ''book"? In effect, you are putting the author's choices under a microscope. The process of close reading should produce a lot of questions. It is when you begin to answer these questions that you are ready to participate thoughtfully in class discussion or write a literary analysis paper that makes the most of your close reading work. Close reading sometimes feels like over-analysing, but don worry. Close reading is a process of finding as much information as you can in order to form as many questions as you can. When it is time to write your paper and formalize your close reading, you'll sort through your work to figure out what is most convincing and helpful to the argument you hope to make and, conversely, what seems like a stretch. It's our responsibility as educators to build students' capacity for independently comprehending a text through close reading. Teaching is about the transfer. The goal is for students is to take what they learn from the study of one text and apply it to the next text they read: How can we ensure that students both reap the requisite knowledge from each text they read and acquire skills to pursue the meaning of other texts independently? I suggest we coach students to ask themselves four basic questions as they reflect on a specific portion of any text, even the shortest: What is the author telling me here? Are there any hard or important words? What does the author want me to understand? How does the author play with language to add to meaning? If students take time to ask themselves these questions while reading and become skilful at answering them, there'll be less need for the teacher to doll the asking. For this to happen, we must develop students' capacity to observe and analyse. First things first: See whether students have noticed the details of a passage and can recount those details in their own words. Note that the challenge here isn't to be brief (as in a summary); it's to be accurate, precise, and clear.

The recent focus on finding evidence in a text has sent students (even in primary grades) scurrying back to their books to retrieve a quote that validates their opinion. But to paraphrase what that quote means in a student's own language, rather than the author's, is more difficult than you might think. Try it with any paragraph. Expressing the same meaning with different words often requires going back to that text a few times to get the details just right. Paraphrasing is pretty low on Bloom's continuum of lower- to higher-order thinking, yet many students stumble even b: here. This is the first stop along the journey to close reading. If students can't paraphrase the basic content of a passage, how can they dig for its deeper meaning? The second basic question about hard or important words encourages students to zoom in on precise meaning. When students are satisfied that they have a basic grasp of what the author is telling them, they're ready to move on to analysing the fine points of content. If students begin their analysis by asking themselves the third question- What does the author want me to understand in this passage?-they'II be on their way to malcing appropriate inferences determining what the author is trying to show without stating it directly.

We can also teach students to read carefully with the eye of a writer, which means helping them analyse craft. How a text is written is as important as the content itself in getting the author's· message across. Just as a movie director focuses the camera on a particular detail to get you to view the scene the way he or she wants you to, authors play with words to get you to see a text their way. Introducing students to some of the tricks authors use opens students' minds to an entirely new realm in close reading.

Q. According to the passage, what is the importance of ' paraphrasing' for students?

Directions: Read the sentence to find out whether there is any grammatical or idiomatic error in it. The error, if any, will be in one part of the sentence. The number of that part is the answer. If there is no error, the answer is (d). (Ignore the errors of punctuation, if any)

Q. Pollution is the introduction (a)/ of contaminants into (b)/ an environment. (c)/ No error (d)

Directions: Read the sentences below carefully and identify the nature of phrase/clause used in the underlined section of the sentences.

Q. The Poor debtor intended to pay back every penny of the money.

Directions: A conclusion is followed by two statements which give us data for the conclusion. Study that data and the conclusion on and mark the correct answer.

Conclusion:

The quality of work produced today cannot be compared with the earlier works.

Statement:

1. Better works are produced today.

2. People compare the works of today with early works.

Directions: Read the sentences below carefully and identify the nature of phrase/clause used in the underlined section of the sentences.

Q. He failed in spite of his best efforts

Directions: Read the following passages carefully and identify most appropriate answer to the questions given at the end of each passage.

Any company can generate simple descriptive statistics about aspects of its business-average revenue per employee, for example, or average order size. But analytics competitors look well beyond basic statistics. These companies use predictive modelling to identify the most profitable customers-plus those with the greater profit potential and the ones mo.st likely to cancel their accounts. They pool data generated in-house and data acquired from outside sources (which they analyze more deeply than do their less statistically savvy competitors) for a comprehensive understanding of their customers. They optimise their supply chains and can thus determine the impact of an unexpected constraint, simulate alternatives and route shipments around problems. They establish prices in real time to get the highest yield possible from each of their customer transactions. They create complex models of how their operational costs relate to their financial performance. Leaders in analytics also use sophisticated experiments to measure the overall impact or "lift" of intervention strategies and then apply the results to continuously improve subsequent analyses. Capital One, for example, conducts more than 30,000 experiments a year, with different interest rates, incentives, direct-mail packaging, and other variables. Its goal is to maximize the likelihood both that potential customers will sign up for credit cards and that they will pay back to Capital One.

Analytics competitors understand that most business functions- even those, like marketing, that have historically depended on art rather than science can be improved with sophisticated quantitative techniques. These organizations don't gain advantage from·one killer app, but rather from multiple applications supporting many parts of the business and, in a few cases, being rolled out for use by customers and suppliers. UPS embodies the evolution from targeted analytics user to comprehensive analytics competitor. Although the company is among the world's most rigorous practitioners of operations research and industrial engineering, its capabilities were, until fairly recently, narrowly focused: Today, UPS is wielding its statistical skill to track the movement of packages and to anticipate and influence the actions of people assessing the likelihood of customer attrition and identifying sources of problems. The UPS Customer Intelligence Group, for example, can accurately predict customer defections by examining usage patterns and complaints.

When the data point to a potential defector, a salesperson contacts that customer to review and resolve the problem, dramatically reducing the loss of accounts. UPS still lacks the breadth of initiatives of a full-bore analytics competitor, but it is heading in that direction. Analytics competitors treat all such activities from all provenances as a single, coherent initiative, often massed under one rubric,such as "information-based strategy" at Capital One or "information based customer management" at Barclays Bank. These programs operate not just under a common label but also under common leadership and with common technology and tools. In traditional companies, "business intelligence" (the term IT people use for analytics and reporting processes and software) is generally managed by departments; number-crunching functions select their own tools, control their own data warehouses, and train their own people. But that way, chaos lies. For one thing, the proliferation of user-developed spreadsheets and databases inevitably leads to multiple versions of key indicators within an organization.

Furthermore, research has shown that between 20% and 40% of spreadsheets contain errors; the more spreadsheets floating around a company, therefore, the more fecund the breeding ground for mistakes. Analytics competitors, by contrast, field centralized groups to ensure that critical data and other resources are well managed and that different parts of the organization can share. data easily, without the impediments of inconsistent formats, definitions, and standards. Some analytics competitors apply the same enterprise approach to people as to technology. Procter & Gamble, for example, recently created a kind of uberanalytics group consisting of more than 100 analysts from such functions as operations, supply chain, sales, consumer research, and' marketing. Although most of the analysts are embedded in business operating units, the group is centrally managed: As a result of this consolidation, P&G; can apply a critical mass of expertise to its most pressing issues. So, for example, sales and marketing analysts supply data on opportunities for growth in existing markets to analysts who design corporate supply networks. The supply chain analysts, in rum, apply their expertise in certain decision-analysis techniques to such new areas as competitive intelligence. The group at P&G; also raises the visibility of analytical and data-based decision making within the company. Previously, P&G;'s crack analysts had improved business processes and saved the firm money; but because they were squirreled away in dispersed domains, many executives didn't know what services they offered or how effective they could be. Now those executives are more likely to tap the company's deep pool of expertise for their projects. Meanwhile, masterful number crunching has become part of the story P &. G tells to investors, the press and the public .

A company wide embrace of analytics impels changes in culture, processes, behavior, and skills for·many employees. And so, like any major transition, it requires leadership from executives at the very top who have a passion for the quantitative approach. Ideally, the principal advocate is the CEO.·Indeed we found several chief executives who have driven the shift to analytics at their companies over the past few years, including LovC1!18D of Harrah's, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, and Rich Fairbank of Capital One. Before he retired from the Sara Lee Balcery Group, former CEO Barry Beracba kept a sign on his desk that summed up bispersoll41 and organizational philosophy: "In God we trust. All others bring data!' We did come across some companies in which a single functional or business unit leader was trying to push analytics throughout the organization, and a few were makii\g some progress. But we found at these lower-level people lacked the clout, perspective, and the cross-functional scope to change the culture in any meaningful way. CEOs leading the analytics charge require both an appreciation and a familiarity with the subject.

A background in statistics isn't necessary, but those leaders must understand the theory belted various quantitative methods so that they recognize those methods limitations-which factors are being weighed and which ones aren't When the CEOs need help grasping quantitative techniques, they rum to experts who understand the business and bow analytics can be applied to it We interviewed several leaders who had retained such advisers, and these executives stressed the need to find someone who can explain things in plain language and be trusted not . to spin the numbers. A few CEOs we spoke with had surrounded themselves with very analytical people-professors, consultants, MIT graduates and the like. But that was a personal preference rather than a necessary practice. Of course, no.t all decisions should be grounded in analytics - at least not wboUy so. Research shows that human beings can make quick, surprisingly accurate assessments of personality and character based on simple observations. For analytics minded leaders then the challenge boils down to knowing when to run with the numbers and when to run with their guts.