IIFT Mock Test - 6 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - IIFT Mock Test - 6 (New Pattern)

Fill in the blanks:-

More often than not, mothers are _____(1)_______ for oddities of behavior in their offspring. ______(2)______, single mothers’ children, raised even in the most difficult of times, do not display ‘outrageous’ patterns of behavior, as do those of nuclear families.

In the following questions, the answer choices suggest alternative arrangements of four or more sentences (denoted by A, B, C, D and so on). Choose the alternative which suggests a coherent paragraph.

A. The situations in which violence occurs and the nature of that violence tends to be clearly defined at least in theory, as in the proverbial Irishman's question: 'Is this a private fight or can anyone join in?

B. So the actual risk to outsiders, though no doubt higher than our societies, is calculable.

C. Probably the only uncontrolled applications of force are those of social superiors to social inferiors and even here there are probably some rules.

D. However binding the obligation to kill, members of feuding families engaged in mutual massacre will be genuinely appalled if by some mischance a bystander or outsider is killed.

Select the correct word or phrase to complete a grammatical and idiomatic sentence.

Agriculture in America has _______ industrial progress.

In the following questions a related pair of words or phrases is followed by four lettered pairs of words or phrases. Select the lettered pair that best expresses a relationship that is least similar to the one expressed in the original pair.

GERMANE : PERTINENT

Arrange sentences A, B, C and D between sentences 1 and 6 to form a logical sequence of the six sentences.

1. The concept of a 'nation-state' assumes a complete correspondence between the boundaries of the nation and the boundaries of those who live in a specific state

A. Then there are members of national collectivizes who live in other countries, making a mockery of the concept.

B. There are always people living in particular states who are not considered to be (and often do not consider themselves to be) members of the hegemonic nation.

C. Even worse, there are nations which never had a state or which are divided across several states.

D. This, of course has been subject to severe criticism and is virtually everywhere a fiction.

6. However, the fiction has been, and continues to be, at the basic nationalist ideologies.

In this question, the word at the top is used in four different ways, numbered (A) to (D). Choose the option in which the usage of the word is Incorrect or Inappropriate.

BUNDLE

In the following questions, a part/two of a sentence has been left blank. You are to select from among the options given below each question, the one which would best fill the blanks. In case of more than one blanks, the first word in the pair, given in the choices, should fill the first gap.

Their achievement in the field of literature is described as_________; sometimes it is even called________.

In the following questions, a part/two of a sentence has been left blank. You are to select from among the options given below each question, the one which would best fill the blanks. In case of more than one blanks, the first word in the pair, given in the choices, should fill the first gap.

The Internet is a medium where users have nearly __________ choices and__________ constraints about where to go and what to do.

Select the correct word or phrase to complete a grammatical and idiomatic sentence.

He has ___, he deals both in books and curios.

For each of the words below, a contextual usage is provided. Pick the word from the alternatives given, that is most inappropriate in the given context.

Disuse : Some words fall into disuse as technology makes objects obsolete.

In the following questions, the answer choices suggest alternative arrangements of four or more sentences (denoted by A, B, C, D and so on). Choose the alternative which suggests a coherent paragraph.

A. To avoid this, the QWERTY layout put the keys most likely to be hit in rapid succession on opposite sides. This made the keyboard slow, the story goes, but that was the idea

B. A different layout, which had been patented by August Dvorak in 1936, was shown to be much faster.

C. The QWERTY design (patented by Christopher Sholes in 1868 and sold to Remington in 1873) aimed to solve a mechanical problem of early typewriters.

D. Yet the Dvorak layout has never been widely adopted, even though (with electric typewriters and then PCs) the anti jamming rationale for QWERTY has been defunct for years.

E. When certain combinations of keys were struck quickly, the type bars often jammed.

In the following questions, the answer choices suggest alternative arrangements of four or more sentences (denoted by A, B, C, D and so on). Choose the alternative which suggests a coherent paragraph.

A. Four days later. Oracle announced its own bid for People Soft, and invited the firm's board to a discussion.

B. Furious that his own plans had been endangered. Peoplesoft's boss, Craig Conway, called Oracle's offer "diabolical", and its boss, Larry Ellison, a "sociopath".

C. In early June, People Soft said that it would buy J.D. Edwards, a smaller rival.

D. Moreover, said Mr. Conway, he "could imagine no price nor combination of price and other condition to recommend accepting the offer".

E. On June 12th, PeopleSoft turned Oracle down.

Each statement has a part missing. Choose the best option from the four options given below the statement to make up the missing part.

The difference in air speed ________ and the tilted wing determines which way it will turn.

Select the correct word or phrase to complete a grammatical and idiomatic sentence.

Does the Deccan Queen Express arrive__ Bombay Central or___ Victoria Terminus?

A sentence has been divided into four parts and marked a, b, c and d. One of these parts contains a mistake in grammar idiom or syntax. Identify that part and mark it as the answer.

A sentence has been divided into four parts and marked a, b, c and d. One of these parts contains a mistake in grammar idiom or syntax. Identify that part and mark it as the answer.

In the following questions, a part/two of a sentence has been left blank. You are to select from among the options given below each question, the one which would best fill the blanks. In case of more than one blanks, the first word in the pair, given in the choices, should fill the first gap.

Football evokes a__________ response in India compared to cricket, that almost ________ the nation.

From the given alternatives, select the one in which the pairs of words have a relationship similar to the one between the bold words.

PREHISTORIC: MEDIEVAL

Arrange sentences A, B, C and D between sentences 1 and 6 to form a logical sequence of the six sentences.

1. Security inks exploit the same principle that causes the vivid and constantly changing colours of a film of oil on water.

A. When two rays of light meet each other after being reflected from these different surfaces, they have each travelled slightly different distances.

B. The key is that the light is bouncing off two surface, that of the oil and that of the water layer below it.

C. The distance the two rays determines which wavelengths, and hence colours, interfere constructively and look bright.

D. Because light is an electromagnetic wave, the peaks and troughs of each ray then interfere either constructively, to appear bright, or destructively, to appear dim.

6. Since the distance the rays travel changes with the angle as you look at the surface, different colours look bright from different viewing angles.

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

When Ratan Tata moved the Supreme Court, claiming his right to privacy had been violated, he called Harish Salve. The choice was not surprising. The former solicitor general had been topping the legal charts ever since he scripted a surprising win for Mukesh Ambani against his brother Anil. That dispute set the gold standard for legal fees. On Mukesh's side were Salve, Rohinton Nariman, and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. The younger brother had an equally formidable line-up led by Ram Jethmalani and Mukul Rohatgi.

The dispute dated back three-and-a-half years to when Anil filed case against his brother for reneging on an agreement to supply 28 million cubic metres of gas per day from its Krishna-Godavari basin fields at a rate of $ 2.34 for 17 years. The average legal fee was Rs. 25 lakh for a full day's appearance, not to mention the overnight stays at Mumbai's five-star suites, business class travel, and on occasion, use of the private jet. Little wonder though that Salve agreed to take on Tata's case pro bono. He could afford philanthropy with one of India's wealthiest tycoons.

The lawyers' fees alone, at a conservative estimate, must have cost the Ambanis at least Rs. 15 crore each. Both the brothers had booked their legal teams in the same hotel, first the Oberoi and, after the 26/ ll Mumbai attacks, the Trident. lt's not the essentials as much as the frills that raise eyebrows. The veteran Jethmalani is surprisingly the most modest in his fees since he does not charge rates according to the strength of the client's purse. But as the crises have multiplied, lawyers'fees have exploded.

The 50 court hearings in the Haldia Petrochemicals vs. the West Bengal Government cost the former a total of Rs. 25 crore in lawyer fees and the 20 hearings in the Bombay Mill Case, which dragged on for three years, cost the mill owners almost Rs. 10 crore. Large corporate firms, which engage star counsels on behalf of the client, also need to know their quirks. For instance, Salve will only accept the first brief. He will never be the second counsel in a case. Some lawyers prefer to be paid partly in cash but the best are content with cheques. Some expect the client not to blink while picking up a dinner tab of Rs. 1.75 lakh at a Chennai five star. A lawyer is known to carry his home linen and curtains with him while travelling on work. A firm may even have to pick up a hot Vertu phone of the moment or a Jaeger-LeCoutre watch of the hour to keep a lawyer in good humour.

Some are even paid to not appear at all for the other side - Aryama Sundaram was retained by Anil Ambani in the gas feud but he did not fight the case. Or take Raytheon when it was fighting the Jindals. Raytheon had paid seven top lawyers a retainer fee of Rs. 2.5 lakh each just to ensure that the Jindals would not be able to make a proper case on a taxation issue. They miscalculated when a star lawyer fought the case at the last minute. "I don't take negative retainers", shrugs Rohatgi, former additional solicitor general. "A Lawyer's job is to appear for any client that comes to him. lt's not for the lawyers to judge if a client is good or bad but the court". Indeed. He is, after all, the lawyer who argued so famously in court that B. Ramalinga Raju did not 'fudge any account in the Satyam Case. All he did was "window dressing".

Some high profile cases have continued for years, providing a steady source of income, from the Scindia succession battle which dates to 1989, to the JetLite Sahara battle now in taxation arbitration to the BCCI which is currently in litigation with Lalit Modi, Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab.

Think of the large law firms as the big Hollywood studios and the senior counsel as the superstar. There are a few familiar faces to be found in most of the big ticket cases, whether it is the Ambani gas case, Vodafone taxation or Bombay Mills case. Explains Salve, "There is a reason why we have more than one senior advocate on a case. When you're arguing, he's reading the court. He picks up a point or a vibe that you may have missed." Says Rajan Karanjawala, whose firm has prepared the briefs for cases ranging from the Tata's recent right to privacy case to Karisma Kapoor's divorce, "The four jewels in the crown today are Salve, Rohatgi, Rohinton Nariman and Singhvi. They have replaced the old guard of Fali Nariman, Soli Sorabjee, Ashok Desai and K.K. Venugopal." He adds, "The one person who defies the generational gap is Jethmalani who was India's leading criminal lawyer in the 1960s and is so today."

The demand for superstar lawyers has far outstripped the supply. So a one-man show by, say, Rohatgi can run up billings of Rs. 40 crore, the same as a mid-sized corporate law firm like Titus and Co that employs 28 juniors. The big law filik such as AZB or Amarchand & Mangaldas or Luthra & Luthra have to do all the groundwork for the counsel, from humouring the clerk to ensure the A-lister turns up on the hearing day to sourcing appropriate foreign judgments in emerging areas such as environmental and patent laws. "We are partners in this. There are so few lawyers and so many matters," points out Diljeet Titus.

As the trust between individuals has broken down, governments have questioned corporates and corporates are questioning each other, and an array of new issues has come up. The courts have become stronger. "The lawyer," says Sundaram, with the flourish that has seen him pick up many Dhurandhares and Senakas at pricey art auctions, "has emerged as the modern day purohit." Each purohit is head priest of a particular style. Says Karanjawala, "Harish is the closest example in today's bar to Fali Nariman; Rohinton has the best law library in his brain; Mukul is easily India's busiest lawyer while Manu Singhvi is the greatest multi-tasker." Salve has managed a fine balancing act where he has represented Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati, Parkash Singh Badal and Amarinder Singh, Lalit Modi and Subhash Chandra and even the Ambani brothers, of course in different cases. Jethmalani is the man to call for anyone in trouble. In judicial circles he is known as the first resort for the last resort. Even Jethmalani's junior Satish Maneshinde, who came to Mumbai in I993 as a penniless law graduate from Karnataka, shot to fame (and wealth) after he got bail for Sanjay Dutt in 1996. Now he owns a plush office in Worli and has become a one-stop shop for celebrities in trouble.

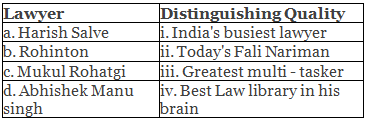

Match the following:

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

When Ratan Tata moved the Supreme Court, claiming his right to privacy had been violated, he called Harish Salve. The choice was not surprising. The former solicitor general had been topping the legal charts ever since he scripted a surprising win for Mukesh Ambani against his brother Anil. That dispute set the gold standard for legal fees. On Mukesh's side were Salve, Rohinton Nariman, and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. The younger brother had an equally formidable line-up led by Ram Jethmalani and Mukul Rohatgi.

The dispute dated back three-and-a-half years to when Anil filed case against his brother for reneging on an agreement to supply 28 million cubic metres of gas per day from its Krishna-Godavari basin fields at a rate of $ 2.34 for 17 years. The average legal fee was Rs. 25 lakh for a full day's appearance, not to mention the overnight stays at Mumbai's five-star suites, business class travel, and on occasion, use of the private jet. Little wonder though that Salve agreed to take on Tata's case pro bono. He could afford philanthropy with one of India's wealthiest tycoons.

The lawyers' fees alone, at a conservative estimate, must have cost the Ambanis at least Rs. 15 crore each. Both the brothers had booked their legal teams in the same hotel, first the Oberoi and, after the 26/ ll Mumbai attacks, the Trident. lt's not the essentials as much as the frills that raise eyebrows. The veteran Jethmalani is surprisingly the most modest in his fees since he does not charge rates according to the strength of the client's purse. But as the crises have multiplied, lawyers'fees have exploded.

The 50 court hearings in the Haldia Petrochemicals vs. the West Bengal Government cost the former a total of Rs. 25 crore in lawyer fees and the 20 hearings in the Bombay Mill Case, which dragged on for three years, cost the mill owners almost Rs. 10 crore. Large corporate firms, which engage star counsels on behalf of the client, also need to know their quirks. For instance, Salve will only accept the first brief. He will never be the second counsel in a case. Some lawyers prefer to be paid partly in cash but the best are content with cheques. Some expect the client not to blink while picking up a dinner tab of Rs. 1.75 lakh at a Chennai five star. A lawyer is known to carry his home linen and curtains with him while travelling on work. A firm may even have to pick up a hot Vertu phone of the moment or a Jaeger-LeCoutre watch of the hour to keep a lawyer in good humour.

Some are even paid to not appear at all for the other side - Aryama Sundaram was retained by Anil Ambani in the gas feud but he did not fight the case. Or take Raytheon when it was fighting the Jindals. Raytheon had paid seven top lawyers a retainer fee of Rs. 2.5 lakh each just to ensure that the Jindals would not be able to make a proper case on a taxation issue. They miscalculated when a star lawyer fought the case at the last minute. "I don't take negative retainers", shrugs Rohatgi, former additional solicitor general. "A Lawyer's job is to appear for any client that comes to him. lt's not for the lawyers to judge if a client is good or bad but the court". Indeed. He is, after all, the lawyer who argued so famously in court that B. Ramalinga Raju did not 'fudge any account in the Satyam Case. All he did was "window dressing".

Some high profile cases have continued for years, providing a steady source of income, from the Scindia succession battle which dates to 1989, to the JetLite Sahara battle now in taxation arbitration to the BCCI which is currently in litigation with Lalit Modi, Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab.

Think of the large law firms as the big Hollywood studios and the senior counsel as the superstar. There are a few familiar faces to be found in most of the big ticket cases, whether it is the Ambani gas case, Vodafone taxation or Bombay Mills case. Explains Salve, "There is a reason why we have more than one senior advocate on a case. When you're arguing, he's reading the court. He picks up a point or a vibe that you may have missed." Says Rajan Karanjawala, whose firm has prepared the briefs for cases ranging from the Tata's recent right to privacy case to Karisma Kapoor's divorce, "The four jewels in the crown today are Salve, Rohatgi, Rohinton Nariman and Singhvi. They have replaced the old guard of Fali Nariman, Soli Sorabjee, Ashok Desai and K.K. Venugopal." He adds, "The one person who defies the generational gap is Jethmalani who was India's leading criminal lawyer in the 1960s and is so today."

The demand for superstar lawyers has far outstripped the supply. So a one-man show by, say, Rohatgi can run up billings of Rs. 40 crore, the same as a mid-sized corporate law firm like Titus and Co that employs 28 juniors. The big law filik such as AZB or Amarchand & Mangaldas or Luthra & Luthra have to do all the groundwork for the counsel, from humouring the clerk to ensure the A-lister turns up on the hearing day to sourcing appropriate foreign judgments in emerging areas such as environmental and patent laws. "We are partners in this. There are so few lawyers and so many matters," points out Diljeet Titus.

As the trust between individuals has broken down, governments have questioned corporates and corporates are questioning each other, and an array of new issues has come up. The courts have become stronger. "The lawyer," says Sundaram, with the flourish that has seen him pick up many Dhurandhares and Senakas at pricey art auctions, "has emerged as the modern day purohit." Each purohit is head priest of a particular style. Says Karanjawala, "Harish is the closest example in today's bar to Fali Nariman; Rohinton has the best law library in his brain; Mukul is easily India's busiest lawyer while Manu Singhvi is the greatest multi-tasker." Salve has managed a fine balancing act where he has represented Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati, Parkash Singh Badal and Amarinder Singh, Lalit Modi and Subhash Chandra and even the Ambani brothers, of course in different cases. Jethmalani is the man to call for anyone in trouble. In judicial circles he is known as the first resort for the last resort. Even Jethmalani's junior Satish Maneshinde, who came to Mumbai in I993 as a penniless law graduate from Karnataka, shot to fame (and wealth) after he got bail for Sanjay Dutt in 1996. Now he owns a plush office in Worli and has become a one-stop shop for celebrities in trouble.

Q. What does a 'negative retainer' refer to?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

When Ratan Tata moved the Supreme Court, claiming his right to privacy had been violated, he called Harish Salve. The choice was not surprising. The former solicitor general had been topping the legal charts ever since he scripted a surprising win for Mukesh Ambani against his brother Anil. That dispute set the gold standard for legal fees. On Mukesh's side were Salve, Rohinton Nariman, and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. The younger brother had an equally formidable line-up led by Ram Jethmalani and Mukul Rohatgi.

The dispute dated back three-and-a-half years to when Anil filed case against his brother for reneging on an agreement to supply 28 million cubic metres of gas per day from its Krishna-Godavari basin fields at a rate of $ 2.34 for 17 years. The average legal fee was Rs. 25 lakh for a full day's appearance, not to mention the overnight stays at Mumbai's five-star suites, business class travel, and on occasion, use of the private jet. Little wonder though that Salve agreed to take on Tata's case pro bono. He could afford philanthropy with one of India's wealthiest tycoons.

The lawyers' fees alone, at a conservative estimate, must have cost the Ambanis at least Rs. 15 crore each. Both the brothers had booked their legal teams in the same hotel, first the Oberoi and, after the 26/ ll Mumbai attacks, the Trident. lt's not the essentials as much as the frills that raise eyebrows. The veteran Jethmalani is surprisingly the most modest in his fees since he does not charge rates according to the strength of the client's purse. But as the crises have multiplied, lawyers'fees have exploded.

The 50 court hearings in the Haldia Petrochemicals vs. the West Bengal Government cost the former a total of Rs. 25 crore in lawyer fees and the 20 hearings in the Bombay Mill Case, which dragged on for three years, cost the mill owners almost Rs. 10 crore. Large corporate firms, which engage star counsels on behalf of the client, also need to know their quirks. For instance, Salve will only accept the first brief. He will never be the second counsel in a case. Some lawyers prefer to be paid partly in cash but the best are content with cheques. Some expect the client not to blink while picking up a dinner tab of Rs. 1.75 lakh at a Chennai five star. A lawyer is known to carry his home linen and curtains with him while travelling on work. A firm may even have to pick up a hot Vertu phone of the moment or a Jaeger-LeCoutre watch of the hour to keep a lawyer in good humour.

Some are even paid to not appear at all for the other side - Aryama Sundaram was retained by Anil Ambani in the gas feud but he did not fight the case. Or take Raytheon when it was fighting the Jindals. Raytheon had paid seven top lawyers a retainer fee of Rs. 2.5 lakh each just to ensure that the Jindals would not be able to make a proper case on a taxation issue. They miscalculated when a star lawyer fought the case at the last minute. "I don't take negative retainers", shrugs Rohatgi, former additional solicitor general. "A Lawyer's job is to appear for any client that comes to him. lt's not for the lawyers to judge if a client is good or bad but the court". Indeed. He is, after all, the lawyer who argued so famously in court that B. Ramalinga Raju did not 'fudge any account in the Satyam Case. All he did was "window dressing".

Some high profile cases have continued for years, providing a steady source of income, from the Scindia succession battle which dates to 1989, to the JetLite Sahara battle now in taxation arbitration to the BCCI which is currently in litigation with Lalit Modi, Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab.

Think of the large law firms as the big Hollywood studios and the senior counsel as the superstar. There are a few familiar faces to be found in most of the big ticket cases, whether it is the Ambani gas case, Vodafone taxation or Bombay Mills case. Explains Salve, "There is a reason why we have more than one senior advocate on a case. When you're arguing, he's reading the court. He picks up a point or a vibe that you may have missed." Says Rajan Karanjawala, whose firm has prepared the briefs for cases ranging from the Tata's recent right to privacy case to Karisma Kapoor's divorce, "The four jewels in the crown today are Salve, Rohatgi, Rohinton Nariman and Singhvi. They have replaced the old guard of Fali Nariman, Soli Sorabjee, Ashok Desai and K.K. Venugopal." He adds, "The one person who defies the generational gap is Jethmalani who was India's leading criminal lawyer in the 1960s and is so today."

The demand for superstar lawyers has far outstripped the supply. So a one-man show by, say, Rohatgi can run up billings of Rs. 40 crore, the same as a mid-sized corporate law firm like Titus and Co that employs 28 juniors. The big law filik such as AZB or Amarchand & Mangaldas or Luthra & Luthra have to do all the groundwork for the counsel, from humouring the clerk to ensure the A-lister turns up on the hearing day to sourcing appropriate foreign judgments in emerging areas such as environmental and patent laws. "We are partners in this. There are so few lawyers and so many matters," points out Diljeet Titus.

As the trust between individuals has broken down, governments have questioned corporates and corporates are questioning each other, and an array of new issues has come up. The courts have become stronger. "The lawyer," says Sundaram, with the flourish that has seen him pick up many Dhurandhares and Senakas at pricey art auctions, "has emerged as the modern day purohit." Each purohit is head priest of a particular style. Says Karanjawala, "Harish is the closest example in today's bar to Fali Nariman; Rohinton has the best law library in his brain; Mukul is easily India's busiest lawyer while Manu Singhvi is the greatest multi-tasker." Salve has managed a fine balancing act where he has represented Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati, Parkash Singh Badal and Amarinder Singh, Lalit Modi and Subhash Chandra and even the Ambani brothers, of course in different cases. Jethmalani is the man to call for anyone in trouble. In judicial circles he is known as the first resort for the last resort. Even Jethmalani's junior Satish Maneshinde, who came to Mumbai in I993 as a penniless law graduate from Karnataka, shot to fame (and wealth) after he got bail for Sanjay Dutt in 1996. Now he owns a plush office in Worli and has become a one-stop shop for celebrities in trouble.

Q. Which of the following is not true about Ram Jethmalani?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

When Ratan Tata moved the Supreme Court, claiming his right to privacy had been violated, he called Harish Salve. The choice was not surprising. The former solicitor general had been topping the legal charts ever since he scripted a surprising win for Mukesh Ambani against his brother Anil. That dispute set the gold standard for legal fees. On Mukesh's side were Salve, Rohinton Nariman, and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. The younger brother had an equally formidable line-up led by Ram Jethmalani and Mukul Rohatgi.

The dispute dated back three-and-a-half years to when Anil filed case against his brother for reneging on an agreement to supply 28 million cubic metres of gas per day from its Krishna-Godavari basin fields at a rate of $ 2.34 for 17 years. The average legal fee was Rs. 25 lakh for a full day's appearance, not to mention the overnight stays at Mumbai's five-star suites, business class travel, and on occasion, use of the private jet. Little wonder though that Salve agreed to take on Tata's case pro bono. He could afford philanthropy with one of India's wealthiest tycoons.

The lawyers' fees alone, at a conservative estimate, must have cost the Ambanis at least Rs. 15 crore each. Both the brothers had booked their legal teams in the same hotel, first the Oberoi and, after the 26/ ll Mumbai attacks, the Trident. lt's not the essentials as much as the frills that raise eyebrows. The veteran Jethmalani is surprisingly the most modest in his fees since he does not charge rates according to the strength of the client's purse. But as the crises have multiplied, lawyers'fees have exploded.

The 50 court hearings in the Haldia Petrochemicals vs. the West Bengal Government cost the former a total of Rs. 25 crore in lawyer fees and the 20 hearings in the Bombay Mill Case, which dragged on for three years, cost the mill owners almost Rs. 10 crore. Large corporate firms, which engage star counsels on behalf of the client, also need to know their quirks. For instance, Salve will only accept the first brief. He will never be the second counsel in a case. Some lawyers prefer to be paid partly in cash but the best are content with cheques. Some expect the client not to blink while picking up a dinner tab of Rs. 1.75 lakh at a Chennai five star. A lawyer is known to carry his home linen and curtains with him while travelling on work. A firm may even have to pick up a hot Vertu phone of the moment or a Jaeger-LeCoutre watch of the hour to keep a lawyer in good humour.

Some are even paid to not appear at all for the other side - Aryama Sundaram was retained by Anil Ambani in the gas feud but he did not fight the case. Or take Raytheon when it was fighting the Jindals. Raytheon had paid seven top lawyers a retainer fee of Rs. 2.5 lakh each just to ensure that the Jindals would not be able to make a proper case on a taxation issue. They miscalculated when a star lawyer fought the case at the last minute. "I don't take negative retainers", shrugs Rohatgi, former additional solicitor general. "A Lawyer's job is to appear for any client that comes to him. lt's not for the lawyers to judge if a client is good or bad but the court". Indeed. He is, after all, the lawyer who argued so famously in court that B. Ramalinga Raju did not 'fudge any account in the Satyam Case. All he did was "window dressing".

Some high profile cases have continued for years, providing a steady source of income, from the Scindia succession battle which dates to 1989, to the JetLite Sahara battle now in taxation arbitration to the BCCI which is currently in litigation with Lalit Modi, Rajasthan Royals and Kings XI Punjab.

Think of the large law firms as the big Hollywood studios and the senior counsel as the superstar. There are a few familiar faces to be found in most of the big ticket cases, whether it is the Ambani gas case, Vodafone taxation or Bombay Mills case. Explains Salve, "There is a reason why we have more than one senior advocate on a case. When you're arguing, he's reading the court. He picks up a point or a vibe that you may have missed." Says Rajan Karanjawala, whose firm has prepared the briefs for cases ranging from the Tata's recent right to privacy case to Karisma Kapoor's divorce, "The four jewels in the crown today are Salve, Rohatgi, Rohinton Nariman and Singhvi. They have replaced the old guard of Fali Nariman, Soli Sorabjee, Ashok Desai and K.K. Venugopal." He adds, "The one person who defies the generational gap is Jethmalani who was India's leading criminal lawyer in the 1960s and is so today."

The demand for superstar lawyers has far outstripped the supply. So a one-man show by, say, Rohatgi can run up billings of Rs. 40 crore, the same as a mid-sized corporate law firm like Titus and Co that employs 28 juniors. The big law filik such as AZB or Amarchand & Mangaldas or Luthra & Luthra have to do all the groundwork for the counsel, from humouring the clerk to ensure the A-lister turns up on the hearing day to sourcing appropriate foreign judgments in emerging areas such as environmental and patent laws. "We are partners in this. There are so few lawyers and so many matters," points out Diljeet Titus.

As the trust between individuals has broken down, governments have questioned corporates and corporates are questioning each other, and an array of new issues has come up. The courts have become stronger. "The lawyer," says Sundaram, with the flourish that has seen him pick up many Dhurandhares and Senakas at pricey art auctions, "has emerged as the modern day purohit." Each purohit is head priest of a particular style. Says Karanjawala, "Harish is the closest example in today's bar to Fali Nariman; Rohinton has the best law library in his brain; Mukul is easily India's busiest lawyer while Manu Singhvi is the greatest multi-tasker." Salve has managed a fine balancing act where he has represented Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati, Parkash Singh Badal and Amarinder Singh, Lalit Modi and Subhash Chandra and even the Ambani brothers, of course in different cases. Jethmalani is the man to call for anyone in trouble. In judicial circles he is known as the first resort for the last resort. Even Jethmalani's junior Satish Maneshinde, who came to Mumbai in I993 as a penniless law graduate from Karnataka, shot to fame (and wealth) after he got bail for Sanjay Dutt in 1996. Now he owns a plush office in Worli and has become a one-stop shop for celebrities in trouble.

Q. What does the phrase 'pro bono' mean?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

With each passing day, it is getting easier to believe that the acceleration in India's economic growth from around 6% to 8% is here to stay. The hard part is trying to explain why this has happened. How this is explained is important since it has a bearing on our future policy.

As per conventional wisdom, India's growth accelerated to around 6% in the nineties from the historical rate of 3.5% because 'reforms' had unleashed the pent-up energies of Indian entrepreneurs long shackled by the socialist raj. It slowed subsequently because 'reforms' had lost momentum. The last three years' spurt in growth is the fortuitous result of a global economic boom. Once the world economy slows down, we will be back to 6% growth - unless we proceed with 'second generation' reforms.

However each of these propositions bristles with problems. It is not true that economic growth rate accelerated to 6% in the nineties. In fact, research has shown that the 'structural break' in India's economic growth occurred not in the early nineties but in the eighties, when economic growth accelerated to close to 6%. The growth in the first decade after reforms was not significantly different from the growth rate in the eighties. The 'reforms' in the sense of market-oriented or even pro-business policies did not commence overnight in 1991, but had commenced earlier. Economic policies in the nineties merely helped consolidate an underlying trend.

Subsequently, the world economy slowed down in 2001-03, which put the brakes on the Indian economy. Then came the crucial change, an acceleration to 8% in 2004-06. This cannot be ascribed to any fresh bout of 'reforms' or even to the global boom. There have been important structural changes in the economy. One is the rise in the savings rate from 23.5% in 2000-01 to 29.1 % in 2004-05. Most of this increase has come from the turnaround in public savings. Thanks to the rise in the savings rate, the economy has moved on to an altogether higher investment rate. The second structural change is enhanced export competitiveness, reflected in the rising share of exports. The total exports (trade plus invisible receipts) / GDP ratio has risen sharply from 16.9% in 2000-01 to 24.6% in 2005-06. A third, less noticed change in recent years is financial deepening. The bank assets / GDP ratio rose from 48% in 200001 to 80% in 2005-06 on the back of a surge in bank credit.

One factor is common to these three structural changes: lower interest rates. The decline in interest rates has helped fiscal consolidation, it has boosted firms' competitiveness and it has led to a huge increase in retail credit. Lower interest rates have been made possible by the rise in inflows on both current and capital accounts. The rise in inflows, in turn, reflects growing overseas confidence in India's economic potential - confidence created by two decades of economic growth of 6%. The sharp depreciation in the rupee in the nineties undoubtedly helped but it is worth recalling that a trend towards rupee depreciation was under way in the eighties itself.

Q. Which of the following statements is incorrect according to the passage?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

With each passing day, it is getting easier to believe that the acceleration in India's economic growth from around 6% to 8% is here to stay. The hard part is trying to explain why this has happened. How this is explained is important since it has a bearing on our future policy.

As per conventional wisdom, India's growth accelerated to around 6% in the nineties from the historical rate of 3.5% because 'reforms' had unleashed the pent-up energies of Indian entrepreneurs long shackled by the socialist raj. It slowed subsequently because 'reforms' had lost momentum. The last three years' spurt in growth is the fortuitous result of a global economic boom. Once the world economy slows down, we will be back to 6% growth - unless we proceed with 'second generation' reforms.

However each of these propositions bristles with problems. It is not true that economic growth rate accelerated to 6% in the nineties. In fact, research has shown that the 'structural break' in India's economic growth occurred not in the early nineties but in the eighties, when economic growth accelerated to close to 6%. The growth in the first decade after reforms was not significantly different from the growth rate in the eighties. The 'reforms' in the sense of market-oriented or even pro-business policies did not commence overnight in 1991, but had commenced earlier. Economic policies in the nineties merely helped consolidate an underlying trend.

Subsequently, the world economy slowed down in 2001-03, which put the brakes on the Indian economy. Then came the crucial change, an acceleration to 8% in 2004-06. This cannot be ascribed to any fresh bout of 'reforms' or even to the global boom. There have been important structural changes in the economy. One is the rise in the savings rate from 23.5% in 2000-01 to 29.1 % in 2004-05. Most of this increase has come from the turnaround in public savings. Thanks to the rise in the savings rate, the economy has moved on to an altogether higher investment rate. The second structural change is enhanced export competitiveness, reflected in the rising share of exports. The total exports (trade plus invisible receipts) / GDP ratio has risen sharply from 16.9% in 2000-01 to 24.6% in 2005-06. A third, less noticed change in recent years is financial deepening. The bank assets / GDP ratio rose from 48% in 200001 to 80% in 2005-06 on the back of a surge in bank credit.

One factor is common to these three structural changes: lower interest rates. The decline in interest rates has helped fiscal consolidation, it has boosted firms' competitiveness and it has led to a huge increase in retail credit. Lower interest rates have been made possible by the rise in inflows on both current and capital accounts. The rise in inflows, in turn, reflects growing overseas confidence in India's economic potential - confidence created by two decades of economic growth of 6%. The sharp depreciation in the rupee in the nineties undoubtedly helped but it is worth recalling that a trend towards rupee depreciation was under way in the eighties itself.

Q. The passage does not discuss:

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

"All raw sugar comes to us this way. You see, it is about the color of maple or brown sugar, but it is not nearly so pure, for it has a great deal of dirt mixed with it when we first get it." "Where does it come from?" inquired Bob.

"Largely from the plantations of Cuba and Porto Rico. Toward the end of the year we also get raw sugar from Java, and by the time this is refined and ready for the market the new crop from the West Indies comes along. In addition to this we get consignments from the Philippine Islands, the Hawaiian Islands, South America, Formosa, and Egypt. I suppose it is quite unnecessary to tell you young men anything of how the cane is grown; of course you know all that."

"I don't believe we do, except in a general way," Bob admitted honestly. "I am ashamed to be so green about a thing at which Dad has been working for years. I don't know why I never asked about it before. I guess I never was interested. I simply took it for granted."

"That's the way with most of us," was the superintendent's kindly answer. "We accept many things in the world without actually knowing much about them, and it is not until something brings our ignorance before us that we take the pains to focus our attention and learn about them. So do not be ashamed that you do not know about sugar raising; I didn't when I was your age. Suppose, then, I give you a little idea of what happens before this raw sugar can come to us."

"I wish you would," exclaimed both boys in a breath.

"Probably in your school geographies you have seen pictures of sugar-cane and know that it is a tall perennial not unlike our Indian corn in appearance; it has broad, flat leaves that sometimes measure as many as three feet in length, and often the stalk itself is twenty feet high. This stalk is jointed like a bamboo pole, the joints being about three inches apart near the roots and increasing in distance the higher one gets from the ground."

"How do they plant it?" Bob asked.

"It can be planted from seed, but this method takes much time and patience; the usual way is to plant it from cuttings, or slips. The first growth from these cuttings is called plant cane; after these are taken off the roots send out ratoons or shoots from which the crop of one or two years, and sometimes longer, is taken. If the soil is not rich and moist replanting is more frequently necessary and in places like Louisiana, where there is annual frost, planting must be done each year. When the cane is ripe it is cut and brought from the field to a central sugar mill, where heavy iron rollers crush from it all the juice. This liquid drips through into troughs from which it is carried to evaporators where the water portion of the sap is eliminated and the juice left; you would be surprised if you were to see this liquid. It looks like nothing so much as the soapy, bluish-gray dish-water that is left in the pan after the dishes have been washed."

"A tempting picture!" Van exclaimed.

"I know it. Sugar isn't very attractive during its process of preparation," agreed Mr. Hennessey. "The sweet liquid left after the water has been extracted is then poured into vacuum pans to be boiled until the crystals form in it, after which it is put into whirling machines, called centrifugal machines that separate the dry sugar from the syrup with which it is mixed. This syrup is later boiled into molasses. The sugar is then dried and packed in these burlap sacks such as you see here, or in hogsheads, and shipped to refineries to be cleansed and whitened."

"Isn't any of the sugar refined in the places where it grows?" queried Bob.

"Practically none. Large refining plants are too expensive to be erected everywhere; it therefore seems better that they should be built in our large cities, where the shipping facilities are good not only for receiving sugar in its raw state but for distributing it after it has been refined and is ready for sale. Here, too, machinery can more easily be bought and the business handled with less difficulty."

Q. Which of the following is the correct sequence of sugar preparation process?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

"All raw sugar comes to us this way. You see, it is about the color of maple or brown sugar, but it is not nearly so pure, for it has a great deal of dirt mixed with it when we first get it." "Where does it come from?" inquired Bob.

"Largely from the plantations of Cuba and Porto Rico. Toward the end of the year we also get raw sugar from Java, and by the time this is refined and ready for the market the new crop from the West Indies comes along. In addition to this we get consignments from the Philippine Islands, the Hawaiian Islands, South America, Formosa, and Egypt. I suppose it is quite unnecessary to tell you young men anything of how the cane is grown; of course you know all that."

"I don't believe we do, except in a general way," Bob admitted honestly. "I am ashamed to be so green about a thing at which Dad has been working for years. I don't know why I never asked about it before. I guess I never was interested. I simply took it for granted."

"That's the way with most of us," was the superintendent's kindly answer. "We accept many things in the world without actually knowing much about them, and it is not until something brings our ignorance before us that we take the pains to focus our attention and learn about them. So do not be ashamed that you do not know about sugar raising; I didn't when I was your age. Suppose, then, I give you a little idea of what happens before this raw sugar can come to us."

"I wish you would," exclaimed both boys in a breath.

"Probably in your school geographies you have seen pictures of sugar-cane and know that it is a tall perennial not unlike our Indian corn in appearance; it has broad, flat leaves that sometimes measure as many as three feet in length, and often the stalk itself is twenty feet high. This stalk is jointed like a bamboo pole, the joints being about three inches apart near the roots and increasing in distance the higher one gets from the ground."

"How do they plant it?" Bob asked.

"It can be planted from seed, but this method takes much time and patience; the usual way is to plant it from cuttings, or slips. The first growth from these cuttings is called plant cane; after these are taken off the roots send out ratoons or shoots from which the crop of one or two years, and sometimes longer, is taken. If the soil is not rich and moist replanting is more frequently necessary and in places like Louisiana, where there is annual frost, planting must be done each year. When the cane is ripe it is cut and brought from the field to a central sugar mill, where heavy iron rollers crush from it all the juice. This liquid drips through into troughs from which it is carried to evaporators where the water portion of the sap is eliminated and the juice left; you would be surprised if you were to see this liquid. It looks like nothing so much as the soapy, bluish-gray dish-water that is left in the pan after the dishes have been washed."

"A tempting picture!" Van exclaimed.

"I know it. Sugar isn't very attractive during its process of preparation," agreed Mr. Hennessey. "The sweet liquid left after the water has been extracted is then poured into vacuum pans to be boiled until the crystals form in it, after which it is put into whirling machines, called centrifugal machines that separate the dry sugar from the syrup with which it is mixed. This syrup is later boiled into molasses. The sugar is then dried and packed in these burlap sacks such as you see here, or in hogsheads, and shipped to refineries to be cleansed and whitened."

"Isn't any of the sugar refined in the places where it grows?" queried Bob.

"Practically none. Large refining plants are too expensive to be erected everywhere; it therefore seems better that they should be built in our large cities, where the shipping facilities are good not only for receiving sugar in its raw state but for distributing it after it has been refined and is ready for sale. Here, too, machinery can more easily be bought and the business handled with less difficulty."

Q. Which of the following statements, as per the paragraph, is incorrect?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

"All raw sugar comes to us this way. You see, it is about the color of maple or brown sugar, but it is not nearly so pure, for it has a great deal of dirt mixed with it when we first get it." "Where does it come from?" inquired Bob.

"Largely from the plantations of Cuba and Porto Rico. Toward the end of the year we also get raw sugar from Java, and by the time this is refined and ready for the market the new crop from the West Indies comes along. In addition to this we get consignments from the Philippine Islands, the Hawaiian Islands, South America, Formosa, and Egypt. I suppose it is quite unnecessary to tell you young men anything of how the cane is grown; of course you know all that."

"I don't believe we do, except in a general way," Bob admitted honestly. "I am ashamed to be so green about a thing at which Dad has been working for years. I don't know why I never asked about it before. I guess I never was interested. I simply took it for granted."

"That's the way with most of us," was the superintendent's kindly answer. "We accept many things in the world without actually knowing much about them, and it is not until something brings our ignorance before us that we take the pains to focus our attention and learn about them. So do not be ashamed that you do not know about sugar raising; I didn't when I was your age. Suppose, then, I give you a little idea of what happens before this raw sugar can come to us."

"I wish you would," exclaimed both boys in a breath.

"Probably in your school geographies you have seen pictures of sugar-cane and know that it is a tall perennial not unlike our Indian corn in appearance; it has broad, flat leaves that sometimes measure as many as three feet in length, and often the stalk itself is twenty feet high. This stalk is jointed like a bamboo pole, the joints being about three inches apart near the roots and increasing in distance the higher one gets from the ground."

"How do they plant it?" Bob asked.

"It can be planted from seed, but this method takes much time and patience; the usual way is to plant it from cuttings, or slips. The first growth from these cuttings is called plant cane; after these are taken off the roots send out ratoons or shoots from which the crop of one or two years, and sometimes longer, is taken. If the soil is not rich and moist replanting is more frequently necessary and in places like Louisiana, where there is annual frost, planting must be done each year. When the cane is ripe it is cut and brought from the field to a central sugar mill, where heavy iron rollers crush from it all the juice. This liquid drips through into troughs from which it is carried to evaporators where the water portion of the sap is eliminated and the juice left; you would be surprised if you were to see this liquid. It looks like nothing so much as the soapy, bluish-gray dish-water that is left in the pan after the dishes have been washed."

"A tempting picture!" Van exclaimed.

"I know it. Sugar isn't very attractive during its process of preparation," agreed Mr. Hennessey. "The sweet liquid left after the water has been extracted is then poured into vacuum pans to be boiled until the crystals form in it, after which it is put into whirling machines, called centrifugal machines that separate the dry sugar from the syrup with which it is mixed. This syrup is later boiled into molasses. The sugar is then dried and packed in these burlap sacks such as you see here, or in hogsheads, and shipped to refineries to be cleansed and whitened."

"Isn't any of the sugar refined in the places where it grows?" queried Bob.

"Practically none. Large refining plants are too expensive to be erected everywhere; it therefore seems better that they should be built in our large cities, where the shipping facilities are good not only for receiving sugar in its raw state but for distributing it after it has been refined and is ready for sale. Here, too, machinery can more easily be bought and the business handled with less difficulty."

Q. Which one of the following is not a essential condition for setting up sugar refining plants?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

Babur's head was throbbing with the persistent ache that dogged him during the monsoon. The warm rain had been falling for three days now but the still. heavy air held no promise of relief. The rains would go on for weeks, even months. Lying back against silken bolsters in his bedchamber in the Agra fort, he tried to imagine the chill, thin rains of Ferghana blowing in over the jagged summit of Mount Beshtor and failed. The punkah above his head hardly disturbed the air. It was hard even to remember what it was like not to feel hot. There was little pleasure just now even in visiting his garden the sodden flowers, soggy ground and overflowing water channels only depressed him.

Babur got up and tried to concentrate on writing an entry in his diary but the words wouldn't come and he pushed his jewel-studded inkwell impatiently aside. Maybe he would go to the women's apartments. He would ask Maham to sing. Sometimes she accompanied herself on the round-bellied, slendernecked lute that had once belonged to Esan Dawlat. Maham lacked her grandmother's but the lute still made a sweet sound in her hands.

Or he might play a game of chess with Humayun. His son had a shrewd, subtle mind - but so, he prided himself, did he and he could usually beat him. It amused him to see Humayun's startled look as he claimed victory with the traditional cry shah mat - 'check-mate', 'the king is at a loss'. Later, they would discuss Babur's plans to launch a campaign when the rains eased against the rulers of Bengal. In their steamy jungles in the Ganges delta, they thought they could defy Moghul authority and deny Babur's overlordship.

'Send for my son Humayun and fetch my chessmen,' Babur ordered a servant. Trying to shake off his lethargy he got up and went to a casement projecting over the riverbank to watch the swollen, muddy waters of the Jumna rushing by. A farmer was leading his bony bullocks along the oozing bank.

Hearing footsteps Babur turned, expecting to see his son, but it was only the white-tunicked servant. 'Majesty, your son begs your forgiveness but he is unwell and cannot leave his chamber.'

What is the matter with him?'

'I do not know, Majesty.'

Humayun was never ill. Perhaps he, too, was suffering from the torpor that came with the monsoon, sapping the energy and spirit of even the most vigorous.

'I will go to him.' Babur wrapped a yellow silk robe around himself and thrust his feet into pointed kidskin slippers. Then he hurried from his apartments to Humayun's on the opposite side of a galleried courtyard, where water was not shooting as it should, in sparkling arcs from the lotus-shaped marble basins of the fountains but pouring over the inundated rims.

Humayun was lying on his bed, arms thrown back, eyes closed, forehead beaded with sweat, shivering. When he heard his father's voice he opened his eyes but they were bloodshot, the pupils dilated. Babur could hear his heavy wheezing breathing. Every scratchy intake of air seemed an effort which hurt him.

'When did this illness begin?'

'Early this morning, Father.'

'Why wasn't I told?' Babur looked angrily at his son's attendants. 'Send for my hakim immediately!' Then he dipped his own silk handkerchief into some water and wiped Humayun's brow. The sweat returned at once - in fact, it was almost running down his face and he seemed to be shivering even more violently now and his teeth had begun to chatter.

'Majesty, the hakim is here.'

Abdul-Malik went immediately to Humayun's bedside, laid a hand on his forehead, pulled back his eyelids and felt his pulse. Then, with increasing concern, he pulled open Humayun's robe and, bending, turned his neatly turbaned head to listen to Humayun's heart.

'What is wrong with him?'

Abdul-Malik paused. 'It is hard to say, Majesty. I need to examine him further.'

'Whatever you require you only have to say...'

I will send for my assistants. If I may be frank, it would be best if you were to leave the chamber, Majesty. I will report to you when l have examined the prince thoroughly - but it looks serious, perhaps even grave. His pulse and heartbeat are weak and rapid.' Without waiting for Babur's reply, Abdul-Malik turned back to his patient. Babur hesitated and, after a glance at his son's waxen trembling face, the room. As attendants closed the doors behind him he found that he, too, was trembling.

A chill closed round his heart. So many times he had feared for Humayun. At Panipat he could have fallen beneath the feet of one of Sultan Ibrahim's war elephants. At Khanua he might have been felled by the slash of a Rajput sword. But he had never thought that Humayun - so healthy and strong - might succumb to sickness. How could he face life without his beloved eldest son? Hindustan and all its riches would be worthless if Humayun died. He would never have come to this sweltering, festering land with its endless hot rains and whining, bloodsucking mosquitoes if he had known this would be the price.

Q. According to this passage, which of the following has not been used to describe Humayun?

Directions for Questions: Answer the questions based on following passage.

Babur's head was throbbing with the persistent ache that dogged him during the monsoon. The warm rain had been falling for three days now but the still. heavy air held no promise of relief. The rains would go on for weeks, even months. Lying back against silken bolsters in his bedchamber in the Agra fort, he tried to imagine the chill, thin rains of Ferghana blowing in over the jagged summit of Mount Beshtor and failed. The punkah above his head hardly disturbed the air. It was hard even to remember what it was like not to feel hot. There was little pleasure just now even in visiting his garden the sodden flowers, soggy ground and overflowing water channels only depressed him.

Babur got up and tried to concentrate on writing an entry in his diary but the words wouldn't come and he pushed his jewel-studded inkwell impatiently aside. Maybe he would go to the women's apartments. He would ask Maham to sing. Sometimes she accompanied herself on the round-bellied, slendernecked lute that had once belonged to Esan Dawlat. Maham lacked her grandmother's but the lute still made a sweet sound in her hands.

Or he might play a game of chess with Humayun. His son had a shrewd, subtle mind - but so, he prided himself, did he and he could usually beat him. It amused him to see Humayun's startled look as he claimed victory with the traditional cry shah mat - 'check-mate', 'the king is at a loss'. Later, they would discuss Babur's plans to launch a campaign when the rains eased against the rulers of Bengal. In their steamy jungles in the Ganges delta, they thought they could defy Moghul authority and deny Babur's overlordship.

'Send for my son Humayun and fetch my chessmen,' Babur ordered a servant. Trying to shake off his lethargy he got up and went to a casement projecting over the riverbank to watch the swollen, muddy waters of the Jumna rushing by. A farmer was leading his bony bullocks along the oozing bank.

Hearing footsteps Babur turned, expecting to see his son, but it was only the white-tunicked servant. 'Majesty, your son begs your forgiveness but he is unwell and cannot leave his chamber.'

What is the matter with him?'

'I do not know, Majesty.'

Humayun was never ill. Perhaps he, too, was suffering from the torpor that came with the monsoon, sapping the energy and spirit of even the most vigorous.

'I will go to him.' Babur wrapped a yellow silk robe around himself and thrust his feet into pointed kidskin slippers. Then he hurried from his apartments to Humayun's on the opposite side of a galleried courtyard, where water was not shooting as it should, in sparkling arcs from the lotus-shaped marble basins of the fountains but pouring over the inundated rims.

Humayun was lying on his bed, arms thrown back, eyes closed, forehead beaded with sweat, shivering. When he heard his father's voice he opened his eyes but they were bloodshot, the pupils dilated. Babur could hear his heavy wheezing breathing. Every scratchy intake of air seemed an effort which hurt him.

'When did this illness begin?'

'Early this morning, Father.'

'Why wasn't I told?' Babur looked angrily at his son's attendants. 'Send for my hakim immediately!' Then he dipped his own silk handkerchief into some water and wiped Humayun's brow. The sweat returned at once - in fact, it was almost running down his face and he seemed to be shivering even more violently now and his teeth had begun to chatter.

'Majesty, the hakim is here.'

Abdul-Malik went immediately to Humayun's bedside, laid a hand on his forehead, pulled back his eyelids and felt his pulse. Then, with increasing concern, he pulled open Humayun's robe and, bending, turned his neatly turbaned head to listen to Humayun's heart.

'What is wrong with him?'

Abdul-Malik paused. 'It is hard to say, Majesty. I need to examine him further.'

'Whatever you require you only have to say...'

I will send for my assistants. If I may be frank, it would be best if you were to leave the chamber, Majesty. I will report to you when l have examined the prince thoroughly - but it looks serious, perhaps even grave. His pulse and heartbeat are weak and rapid.' Without waiting for Babur's reply, Abdul-Malik turned back to his patient. Babur hesitated and, after a glance at his son's waxen trembling face, the room. As attendants closed the doors behind him he found that he, too, was trembling.

A chill closed round his heart. So many times he had feared for Humayun. At Panipat he could have fallen beneath the feet of one of Sultan Ibrahim's war elephants. At Khanua he might have been felled by the slash of a Rajput sword. But he had never thought that Humayun - so healthy and strong - might succumb to sickness. How could he face life without his beloved eldest son? Hindustan and all its riches would be worthless if Humayun died. He would never have come to this sweltering, festering land with its endless hot rains and whining, bloodsucking mosquitoes if he had known this would be the price.

Q. Babur was feeling depressed because: