Practice Test for XAT - 3 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - Practice Test for XAT - 3

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliament's price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q. The passage can best be described as a

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliaments price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q.The passage suggests that the view referred to in first paragraph argued that

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliaments price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that Webb would be most likely to agree with which of the following statements regarding garrison government?

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliaments price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q. According to the passage, Webb views Charles II as the “proper successor” (line 13) of the Tudor monarchs and Cromwell because Charles II

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliaments price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q. According to Webb’s view of colonial history, which of the following was (were) true of the merchants and nobility?

I. They were opposed to policies formulated by Charles II that would have transformed the colonies into capitalistic oligarchies.

II. They were opposed to attempts by the English crown to limit the power of the legislative assemblies.

III. They were united with small farmers in their opposition to the stationing of English troops in the colonies.

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

A long-held view of the history of the English colonies that became the United States has been that England’s policy toward these colonies before 1763 was dictated by commercial interests and that a change to a more imperial policy, dominated by expansionist militarist objectives, generated the tensions that ultimately led to the American Revolution. In a recent study, Stephen Saunders Webb has presented a formidable challenge to this view. According to Webb, England already had a military imperial policy for more than a century before the American Revolution. He sees Charles II, the English monarch between 1660 and 1685, as the proper successor of the Tudor monarchs of the sixteenth century and of Oliver Cromwell, all of whom were bent on extending centralized executive power over England’s possessions through the use of what Webb calls “garrison government.” Garrison government allowed the colonists a legislative assembly, but real authority, in Webb’s view, belonged to the colonial governor, who was appointed by the king and supported by the “garrison,” that is, by the local contingent of English troops under the colonial governor’s command.

According to Webb, the purpose of garrison government was to provide military support for a royal policy designed to limit the power of the upper classes in the American colonies. Webb argues that the colonial legislative assemblies represented the interests not of the common people but of the colonial upper classes, a coalition of merchants and nobility who favored self-rule and sought to elevate legislative authority at the expense of the executive. It was, according to Webb, the colonial governors who favored the small farmer, opposed the plantation system, and tried through taxation to break up large holdings of land. Backed by the military presence of the garrison, these governors tried to prevent the gentry and merchants, allied in the colonial assemblies, from transforming colonial America into a capitalistic oligarchy.

Webb’s study illuminates the political alignments that existed in the colonies in the century prior to the American Revolution, but his view of the crown’s use of the military as an instrument of colonial policy is not entirely convincing. England during the seventeenth century was not noted for its military achievements. Cromwell did mount England’s most ambitious overseas military expedition in more than a century, but it proved to be an utter failure. Under Charles II, the English army was too small to be a major instrument of government. Not until the war with France in 1697 did William III persuade Parliament to create a professional standing army, and Parliaments price for doing so was to keep the army under tight legislative control. While it may be true that the crown attempted to curtail the power of the colonial upper classes, it is hard to imagine how the English army during the seventeenth century could have provided significant military support for such a policy.

Q. The author suggests that if William III had wanted to make use of the standing army to administer garrison government in the American colonies, he would have had to

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. The primary purpose of the passage is to

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that the protein sequences of the capsid that vary most among strains of rhinovirus are those

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that a cell lacking delta-receptors will be

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. Which of the following research strategies for developing a defense against the common cold would the author be likely to find most promising?

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that the purpose of Colonno’s experiments was to determine whether

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Viruses, infectious particles consisting of nucleic acid packaged in a protein coat (the capsid), are difficult to resist. Unable to reproduce outside a living cell, viruses reproduce only by subverting the genetic mechanisms of a host cell. In one kind of viral life cycle, the virus first binds to the cell’s surface, then penetrates the cell and sheds its capsid. The exposed viral nucleic acid produces new viruses from the contents of the cell. Finally, the cell releases the viral progeny, and a new cell cycle of infection begins. The human body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies: complex, highly specific proteins that selectively bind to foreign molecules such as viruses. An antibody can either interfere with a virus’s ability to bind to a cell, or can prevent it from releasing its nucleic acid.

Unfortunately, the common cold, produced most often by rhinoviruses, is intractable to antiviral defense. Humans have difficulty resisting colds because rhinoviruses are so diverse, including at least 100 strains. The strains differ most in the molecular structure of the proteins in their capsids. Since disease-fighting antibodies bind to the capsid, an antibody developed to protect against one rhinovirus strain is useless against other strains. Different antibodies must be produced for each strain.

A defense against rhinoviruses might nonetheless succeed by exploiting hidden similarities among the rhinovirus strains. For example, most rhinovirus strains bind to the same kind of molecule (delta-receptors) on a cell’s surface when they attack human cells. Colonno, taking advantage of these common receptors, devised a strategy for blocking the attachment of rhinoviruses to their appropriate receptors. Rather than fruitlessly searching for an antibody that would bind to all rhinoviruses, Colonno realized that an antibody binding to the common receptors of a human cell would prevent rhinoviruses from initiating an infection. Because human cells normally do not develop antibodies to components of their own cells, Colonno injected human cells into mice, which did produce an antibody to the common receptor. In isolated human cells, this antibody proved to be extraordinarily effective at thwarting the rhinovirus. Moreover, when the antibody was given to chimpanzees, it inhibited rhinoviral growth, and in humans it lessened both the severity and duration of cold symptoms.

Another possible defense against rhinoviruses was proposed by Rossman, who described rhinoviruses’ detailed molecular structure. Rossman showed that protein sequences common to all rhinovirus strains lie at the base of a deep “canyon” scoring each face of the capsid. The narrow opening of this canyon possibly prevents the relatively large antibody molecules from binding to the common sequence, but smaller molecules might reach it. Among these smaller, non - antibody molecules, some might bind to the common sequence, lock the nucleic acid in its coat, and thereby prevent the virus from reproducing.

Q. According to the passage, Rossman’s research suggests that

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. According to the passage, the assumption that the introduction of a real particle into a vacuum raises the total energy of that region of space has been cast into doubt by which of the following?

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. It can be inferred from the passage that scientists are currently making efforts to observe which of the following events?

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. Physicist's recent investigations of the decay of the vacuum, as described in the passage, most closely resemble which of the following hypothetical events in other disciplines?

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. According to the passage, the author considers the reduction of energy in an empty region of space to which a real particle has been added to be

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. According to the passage, virtual particles differ from real particles in which of the following ways?

I. Virtual particles have extremely short lifetimes.

II. Virtual particles are created in an intense electric field.

III. Virtual particles cannot be detected directly.

Read the passage carefully and answer within the context

Classical physics defines the vacuum as a state of absence: a vacuum is said to exist in a region of space if there is nothing in it. In the quantum field theories that describe the physics of elementary particles, the vacuum becomes somewhat more complicated. Even in empty space, particles can appear spontaneously as a result of fluctuations of the vacuum. For example, an electron and a positron, or antielectron, can be created out of the void. Particles created in this way have only a fleeting existence; they are annihilated almost as soon as they appear, and their presence can never be detected directly. They are called virtual particles in order to distinguish them from real particles, whose lifetimes are not constrained in the same way, and which can be detected. Thus it is still possible to define that vacuum as a space that has no real particles in it.

One might expect that the vacuum would always be the state of lowest possible energy for a given region of space. If an area is initially empty and a real particle is put into it, the total energy, it seems, should be raised by at least the energy equivalent of the mass of the added particle. A surprising result of some recent theoretical investigations is that this assumption is not invariably true. There are conditions under which the introduction of a real particle of finite mass into an empty region of space can reduce the total energy. If the reduction in energy is great enough, an electron and a positron will be spontaneously created. Under these conditions the electron and positron are not a result of vacuum fluctuations but are real particles, which exist indefinitely and can be detected. In other words, under these conditions the vacuum is an unstable state and can decay into a state of lower energy; i.e., one in which real particles are created.

The essential condition for the decay of the vacuum is the presence of an intense electric field. As a result of the decay of the vacuum, the space permeated by such a field can be said to acquire an electric charge, and it can be called a charged vacuum. The particles that materialize in the space make the charge manifest. An electric field of sufficient intensity to create a charged vacuum is likely to be found in only one place: in the immediate vicinity of a superheavy atomic nucleus, one with about twice as many protons as the heaviest natural nuclei known. A nucleus that large cannot be stable, but it might be possible to assemble one next to a vacuum for long enough to observe the decay of the vacuum. Experiments attempting to achieve this are now under way.

Q. The author’s assertions concerning the conditions that lead to the decay of the vacuum would be most weakened if which of the following occurred?

There are five sentences which need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph. Key in the most appropriate sequence.

A. Similarly, turning to caste, even though being lower caste is undoubtedly a separate cause of disparity, its impact is all the greater when the lower-caste families also happen to be poor.

B. Belonging to a privileged class can help a woman to overcome many barriers that obstruct women from less thriving classes.

C. It is the interactive presence of these two kinds of deprivation - being low class and being female - that massively impoverishes women from the less privileged classes.

D. A congruence of class deprivation and gender discrimination can blight the lives of poorer women very severely.

E. Gender is certainly a contributor to societal inequality, but it does not act independently of class.

There are five sentences which need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph. Key in the most appropriate sequence.

A. When identity is thus ‘defined by contrast’, divergence with the West becomes central.

B. Indian religious literature such as the Bhagavad Gita or the Tantric texts, which are identified as differing from secular writings seen as ‘western’, elicits much greater interest in the West than do other Indian writings, including India's long history of heterodoxy.

C. There is a similar neglect of Indian writing on non-religious subjects, from mathematics, epistemology and natural science to economics and linguistics.

D. Through selective emphasis that point up differences with the West, other civilizations can, in this way, be redefined in alien terms, which can be exotic and charming, or else bizarre and terrifying, or simply strange and engaging.

E.The exception is the Kamasutra in which western readers have managed to cultivate an interest.

There are five sentences which need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph. Key in the most appropriate sequence.

A.This is now orthodoxy to which I subscribe - up to a point.

B.It emerged from the mathematics of chance and statistics.

C.Therefore the risk is measurable and manageable.

D.The fundamental concept: Prices are not predictable, but the mathematical laws of chance can describe their fluctuations.

E.This is how what business schools now call modern finance was born.

There are five sentences which need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph. Key in the most appropriate sequence.

A. He felt justified in bypassing Congress altogether on a variety of moves.

B. At times he was fighting the entire Congress.

C. Bush felt he had a mission to restore power to the presidency.

D. Bush was not fighting just the democrats.

E. Representative democracy is a messy business, and a CEO of the White House does not like a legislature of second guessers and time wasters.

Key in the option which correctly summarizes the above paragraph :

You seemed at first to take no notice of your school-fellows, or rather to set yourself against them because they were strangers to you. They knew as little of you as you did of them; this would have been the reason for their keeping aloof from you as well, which you would have felt as a hardship. Learn never to conceive a prejudice against others because you know nothing of them. It is bad reasoning, and makes enemies of half the world. Do not think ill of them till they behave ill to you; and then strive to avoid the faults which you see in them. This will disarm their hostility sooner than pique or resentment or complaint.

In this paragraph last sentence that completes the paragraph has been deleted. From the given options chooses the sentence that completes the paragraph in the most appropriate way.

Adorno’s account of import and function distinguishes his sociology of art from both hermeneutical and empirical approaches. He argues that, both as categories and as phenomena, import and function need to be understood in terms of each other. On one hand, an artwork’s import and its functions in society can be diametrically opposed. On other hand, one cannot give a proper account of an artwork’s social functions if one does not raise import-related questions about their significance. So too, an artwork’s import embodies the work’s social functions and has potential relevance for various social contexts.

In this paragraph last sentence that completes the paragraph has been deleted. From the given options chooses the sentence that completes the paragraph in the most appropriate way.

War was also widely seen before 1914 by the upper class across Europe as an assertion of masculine honour, like a duel, as it were, only on a much bigger scale. Duelling was a common way of avenging real or imagined slights to a man’s honour in virtually every European country at the time. Only in Britain had it died out: the point of a duel was to vindicate one’s manly honour by standing unmoving as your opponent fired a bullet at you at twenty or thirty paces, and the invention of modern cricket, in which a man was required to face down a different kind of round, hard object as it hurtled towards him from the other end of the wicket, was a satisfactory(and comfortingly legal) substitute.

Out of the given statements, 4 of them can be grouped together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify one odd one out into the following sentences:

(1) Though the air is chilly at dawn and night, the sun can be harsh on your face and skin, making it feel sunburnt or wrinkled; just as one takes care of nourishing the skin, with the various lotions and moisturizes, it is also equally important to take care of the body with the right nourishment this season.

(2) Winter! The weather where you not just bring out those woollen sweaters and mufflers, but also want to just tuck yourself in, sipping hot tea or soup; but one has to drag oneself off the bed and run around doing the various chores; some indoors and some outdoors.

(3) Winter abounds with fruits like apples, custard apples, oranges, kiwis, the ever present bananas and pomegranates. All fruits have their own nutritional value and can work wonders if added to your winter diet. Majority of them are rich in vitamins C,D and E, and antioxidants and fibre. As our intake of water during winter reduces drastically, these fruits can provide the necessary fibre in the digestive system.

(4) Unlike what you might expect,the overwhelming majority of cold-weather casualties do not result from vehicular accidents, falls on ice or snow-related activities. Rather,they are attributable to leading killers like heart disease, stroke and respiratory disease,and are especially common among septuagenarians and octagenarians.

(5) While we lean more towards the intake of fluids in the summer,our food habits change during the winter;one craves for hot food, sometimes even spicy ones.

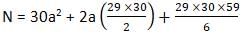

What is the remainder obtained when the sum of the squares of any thirty consecutive natural numbers is divided by 12?

x and y are natural numbers such that x > y > 1. If 8! is divisible by x2 × y2, then how many such sets (x, y) are possible?

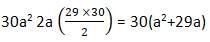

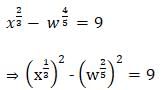

w, x, y and z are natural numbers such that:

(i) logy x = 3/2

(ii) logz w = 5/4

(iii) y – z = 9

Q. What is the value of ‘x – w’?

A right angled triangle is given. Draw a line that is parallel to the hypotenuse, leaving a smaller triangle. There was a 35% reduction in the length of the hypotenuse of the triangle. If the area of the original triangle was 34 cm2, what is the area (in cm2) of the smaller triangle?