SAT Mock Test - 1 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - SAT Mock Test - 1

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. The main purpose of the passage is to

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. The main purpose of the passage is to

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. Which choice best summarizes the first two paragraphs of the passage (lines 1-14)?

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. The narrator indicates that the particular nature of Emma’s upbringing resulted in her being

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. As used in line 26, “directed” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. As used in line 54, “want” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. It can most reasonably be inferred that after Miss Taylor married, she had

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage:

This passage is adapted from Jane Austen, Emma, originally published in 1815.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich,

with a comfortable home and happy disposition,

seemed to unite some of the best blessings of

existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in

(5) the world with very little to distress or vex her.

She was the youngest of the two daughters of a

most affectionate, indulgent father, and had, in

consequence of her sister’s marriage, been mistress of

his house from a very early period. Her mother had

(10) died too long ago for her to have more than an

indistinct remembrance of her caresses, and her

place had been supplied by an excellent woman as

governess, who had fallen little short of a mother in affection.

(15) Sixteen years had Miss Taylor been in

Mr. Woodhouse’s family, less as a governess than a

friend, very fond of both daughters, but particularly

of Emma. Between them it was more the intimacy

of sisters. Even before Miss Taylor had ceased to hold

(20) the nominal office of governess, the mildness of her

temper had hardly allowed her to impose any

restraint; and the shadow of authority being now

long passed away, they had been living together as friend and

friend very mutually attached, and Emma

(25) doing just what she liked; highly esteeming

Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by

her own.

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the

power of having rather too much her own way, and a

(30) disposition to think a little too well of herself; these

were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her

many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at

present so unperceived, that they did not by any

means rank as misfortunes with her.

(35) Sorrow came—a gentle sorrow—but not at

all in the shape of any disagreeable

consciousness.—Miss Taylor married. It was

Miss Taylor’s loss which first brought grief. It was on

the wedding-day of this beloved friend that Emma

(40) first sat in mournful thought of any continuance.

The wedding over and the bride-people gone, her

father and herself were left to dine together, with no

prospect of a third to cheer a long evening. Her

father composed himself to sleep after dinner, as

(45) usual, and she had then only to sit and think of what

she had lost.

The event had every promise of happiness for her

friend. Mr. Weston was a man of unexceptionable

character, easy fortune, suitable age and pleasant

(50) manners; and there was some satisfaction in

considering with what self-denying, generous

friendship she had always wished and promoted the

match; but it was a black morning’s work for her.

The want of Miss Taylor would be felt every hour of

(55) every day. She recalled her past kindness—the

kindness, the affection of sixteen years—how she had

taught and how she had played with her from five

years old—how she had devoted all her powers to

attach and amuse her in health—and how nursed her

(60) through the various illnesses of childhood. A large

debt of gratitude was owing here; but the intercourse

of the last seven years, the equal footing and perfect

unreserve which had soon followed Isabella’s

marriage on their being left to each other, was yet a

(65) dearer, tenderer recollection. It had been a friend and

companion such as few possessed, intelligent,

well-informed, useful, gentle, knowing all the ways of

the family, interested in all its concerns, and

peculiarly interested in herself, in every pleasure,

(70) every scheme of her’s;—one to whom she could

speak every thought as it arose, and who had such an

affection for her as could never find fault.

How was she to bear the change?—It was true that

her friend was going only half a mile from them; but

(75) Emma was aware that great must be the difference

between a Mrs. Weston only half a mile from them,

and a Miss Taylor in the house; and with all her

advantages, natural and domestic, she was now in

great danger of suffering from intellectual solitude.

(80) She dearly loved her father, but he was no

companion for her. He could not meet her in

conversation, rational or playful.

The evil of the actual disparity in their ages (and

Mr. Woodhouse had not married early) was much

(85) increased by his constitution and habits; for having

been a valetudinarian* all his life, without activity of

mind or body, he was a much older man in ways

than in years; and though everywhere beloved for the

friendliness of his heart and his amiable temper, his

(90) talents could not have recommended him at

any time.

* a person in weak health who is overly concerned with his or her ailments

Q. Which situation is most similar to the one described in lines 84-92 (“The evil . . . time”)?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material:

This passage is adapted from Marina Gorbis, The Nature of the Future: Dispatches from the Socialstructed World. ©2013 by Marina Gorbis.

Visitors to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and

1970s always marveled at the gap between what they

saw in state stores—shelves empty or filled with

things no one wanted—and what they saw in

(5) people’s homes: nice furnishings and tables filled

with food. What filled the gap? A vast informal

economy driven by human relationships, dense

networks of social connections through which people

traded resources and created value. The Soviet people

(10) didn’t plot how they would build these networks. No

one was teaching them how to maximize their

connections the way social marketers eagerly teach us today. Their

networks evolved naturally, out of

necessity; that was the only way to survive.

(15) Today, all around the world, we are seeing

a new kind of network of relationship-driven

economics emerging, with individuals joining forces

sometimes to fill the gaps left by existing

institutions—corporations, governments,

(20) educational establishments—and sometimes creating

new products, services, and knowledge that no

institution is able to provide. Empowered by

computing and communication technologies that

have been steadily building village-like networks on a

(25) global scale, we are infusing more and more of our

economic transactions with social connectedness.

The new technologies are inherently social and

personal. They help us create communities around

interests, identities, and common personal

(30) challenges. They allow us to gain direct access to a

worldwide community of others. And they take

anonymity out of our economic transactions. We can

assess those we don’t know by checking their

reputations as buyers and sellers on eBay or by

(35) following their Twitter streams. We can look up their

friends on Facebook and watch their YouTube

videos. We can easily get people’s advice on where to

find the best shoemaker in Brazil, the best

programmer in India, and the best apple farmer in

(40) our local community. We no longer have to rely on

bankers or venture capitalists as the only sources of

funding for our ideas. We can raise funds directly

from individuals, most of whom we don’t even know,

through websites that allow people to

(45) post descriptions of their projects and generate

donations, investments, or loans.

We are moving away from the dominance of the

depersonalized world of institutional production and

creating a new economy around social connections

(50) and social rewards—a process I call socialstructing.

Others have referred to this model of production as

social, commons-based, or peer-to-peer. Not only is

this new social economy bringing with it an

unprecedented level of familiarity and connectedness

(55) to both our global and our local economic exchanges,

but it is also changing every domain of our lives,

from finance to education and health. It is rapidly

ushering in a vast array of new opportunities for us

to pursue our passions, create new types of

(60) businesses and charitable organizations, redefine the

nature of work, and address a wide range of

problems that the prevailing formal economy has

neglected, if not caused.

Socialstructing is in fact enabling not only a new

(65) kind of global economy but a new kind of society, in

which amplified individuals—individuals

empowered with technologies and the collective

intelligence of others in their social network—can

take on many functions that previously only large

(70) organizations could perform, often more efficiently,

at lower cost or no cost at all, and with much greater

ease. Socialstructing is opening up a world of what

my colleagues Jacques Vallée and Bob Johansen

describe as the world of impossible futures, a world

(75) in which a large software firm can be displaced by

weekend software hackers, and rapidly orchestrated

social movements can bring down governments in a

matter of weeks. The changes are exciting and

unpredictable. They threaten many established

(80) institutions and offer a wealth of opportunities for

individuals to empower themselves, find rich new

connections, and tap into a fast-evolving set of new

resources in everything from health care to education

and science.

(85) Much has been written about how technology

distances us from the benefits of face-to-face

communication and quality social time. I think those

are important concerns. But while the quality of our

face-to-face interactions is changing, the

(90) countervailing force of socialstructing is connecting

us at levels never seen before, opening up new

opportunities to create, learn, and share.

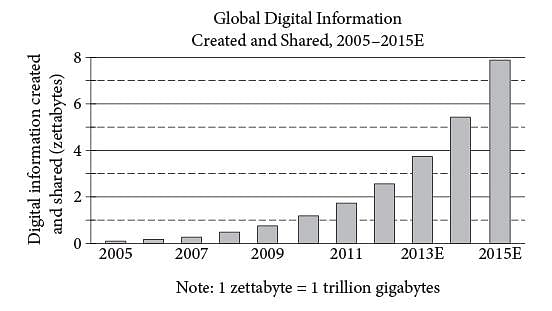

The following graph, from a 2011 report from the International Data Corporation, projects trends in digital information use to 2015 (E = Estimated).

Q. As used in line 10, “plot” most nearly means

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material:

This passage is adapted from Marina Gorbis, The Nature of the Future: Dispatches from the Socialstructed World. ©2013 by Marina Gorbis.

Visitors to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and

1970s always marveled at the gap between what they

saw in state stores—shelves empty or filled with

things no one wanted—and what they saw in

(5) people’s homes: nice furnishings and tables filled

with food. What filled the gap? A vast informal

economy driven by human relationships, dense

networks of social connections through which people

traded resources and created value. The Soviet people

(10) didn’t plot how they would build these networks. No

one was teaching them how to maximize their

connections the way social marketers eagerly teach us today. Their

networks evolved naturally, out of

necessity; that was the only way to survive.

(15) Today, all around the world, we are seeing

a new kind of network of relationship-driven

economics emerging, with individuals joining forces

sometimes to fill the gaps left by existing

institutions—corporations, governments,

(20) educational establishments—and sometimes creating

new products, services, and knowledge that no

institution is able to provide. Empowered by

computing and communication technologies that

have been steadily building village-like networks on a

(25) global scale, we are infusing more and more of our

economic transactions with social connectedness.

The new technologies are inherently social and

personal. They help us create communities around

interests, identities, and common personal

(30) challenges. They allow us to gain direct access to a

worldwide community of others. And they take

anonymity out of our economic transactions. We can

assess those we don’t know by checking their

reputations as buyers and sellers on eBay or by

(35) following their Twitter streams. We can look up their

friends on Facebook and watch their YouTube

videos. We can easily get people’s advice on where to

find the best shoemaker in Brazil, the best

programmer in India, and the best apple farmer in

(40) our local community. We no longer have to rely on

bankers or venture capitalists as the only sources of

funding for our ideas. We can raise funds directly

from individuals, most of whom we don’t even know,

through websites that allow people to

(45) post descriptions of their projects and generate

donations, investments, or loans.

We are moving away from the dominance of the

depersonalized world of institutional production and

creating a new economy around social connections

(50) and social rewards—a process I call socialstructing.

Others have referred to this model of production as

social, commons-based, or peer-to-peer. Not only is

this new social economy bringing with it an

unprecedented level of familiarity and connectedness

(55) to both our global and our local economic exchanges,

but it is also changing every domain of our lives,

from finance to education and health. It is rapidly

ushering in a vast array of new opportunities for us

to pursue our passions, create new types of

(60) businesses and charitable organizations, redefine the

nature of work, and address a wide range of

problems that the prevailing formal economy has

neglected, if not caused.

Socialstructing is in fact enabling not only a new

(65) kind of global economy but a new kind of society, in

which amplified individuals—individuals

empowered with technologies and the collective

intelligence of others in their social network—can

take on many functions that previously only large

(70) organizations could perform, often more efficiently,

at lower cost or no cost at all, and with much greater

ease. Socialstructing is opening up a world of what

my colleagues Jacques Vallée and Bob Johansen

describe as the world of impossible futures, a world

(75) in which a large software firm can be displaced by

weekend software hackers, and rapidly orchestrated

social movements can bring down governments in a

matter of weeks. The changes are exciting and

unpredictable. They threaten many established

(80) institutions and offer a wealth of opportunities for

individuals to empower themselves, find rich new

connections, and tap into a fast-evolving set of new

resources in everything from health care to education

and science.

(85) Much has been written about how technology

distances us from the benefits of face-to-face

communication and quality social time. I think those

are important concerns. But while the quality of our

face-to-face interactions is changing, the

(90) countervailing force of socialstructing is connecting

us at levels never seen before, opening up new

opportunities to create, learn, and share.

The following graph, from a 2011 report from the International Data Corporation, projects trends in digital information use to 2015 (E = Estimated).

Q. The references to the shoemaker, the programmer, and the apple farmer in lines 37-40 (“We can easily . . . community”) primarily serve to

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material:

This passage is adapted from Marina Gorbis, The Nature of the Future: Dispatches from the Socialstructed World. ©2013 by Marina Gorbis.

Visitors to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and

1970s always marveled at the gap between what they

saw in state stores—shelves empty or filled with

things no one wanted—and what they saw in

(5) people’s homes: nice furnishings and tables filled

with food. What filled the gap? A vast informal

economy driven by human relationships, dense

networks of social connections through which people

traded resources and created value. The Soviet people

(10) didn’t plot how they would build these networks. No

one was teaching them how to maximize their

connections the way social marketers eagerly teach us today. Their

networks evolved naturally, out of

necessity; that was the only way to survive.

(15) Today, all around the world, we are seeing

a new kind of network of relationship-driven

economics emerging, with individuals joining forces

sometimes to fill the gaps left by existing

institutions—corporations, governments,

(20) educational establishments—and sometimes creating

new products, services, and knowledge that no

institution is able to provide. Empowered by

computing and communication technologies that

have been steadily building village-like networks on a

(25) global scale, we are infusing more and more of our

economic transactions with social connectedness.

The new technologies are inherently social and

personal. They help us create communities around

interests, identities, and common personal

(30) challenges. They allow us to gain direct access to a

worldwide community of others. And they take

anonymity out of our economic transactions. We can

assess those we don’t know by checking their

reputations as buyers and sellers on eBay or by

(35) following their Twitter streams. We can look up their

friends on Facebook and watch their YouTube

videos. We can easily get people’s advice on where to

find the best shoemaker in Brazil, the best

programmer in India, and the best apple farmer in

(40) our local community. We no longer have to rely on

bankers or venture capitalists as the only sources of

funding for our ideas. We can raise funds directly

from individuals, most of whom we don’t even know,

through websites that allow people to

(45) post descriptions of their projects and generate

donations, investments, or loans.

We are moving away from the dominance of the

depersonalized world of institutional production and

creating a new economy around social connections

(50) and social rewards—a process I call socialstructing.

Others have referred to this model of production as

social, commons-based, or peer-to-peer. Not only is

this new social economy bringing with it an

unprecedented level of familiarity and connectedness

(55) to both our global and our local economic exchanges,

but it is also changing every domain of our lives,

from finance to education and health. It is rapidly

ushering in a vast array of new opportunities for us

to pursue our passions, create new types of

(60) businesses and charitable organizations, redefine the

nature of work, and address a wide range of

problems that the prevailing formal economy has

neglected, if not caused.

Socialstructing is in fact enabling not only a new

(65) kind of global economy but a new kind of society, in

which amplified individuals—individuals

empowered with technologies and the collective

intelligence of others in their social network—can

take on many functions that previously only large

(70) organizations could perform, often more efficiently,

at lower cost or no cost at all, and with much greater

ease. Socialstructing is opening up a world of what

my colleagues Jacques Vallée and Bob Johansen

describe as the world of impossible futures, a world

(75) in which a large software firm can be displaced by

weekend software hackers, and rapidly orchestrated

social movements can bring down governments in a

matter of weeks. The changes are exciting and

unpredictable. They threaten many established

(80) institutions and offer a wealth of opportunities for

individuals to empower themselves, find rich new

connections, and tap into a fast-evolving set of new

resources in everything from health care to education

and science.

(85) Much has been written about how technology

distances us from the benefits of face-to-face

communication and quality social time. I think those

are important concerns. But while the quality of our

face-to-face interactions is changing, the

(90) countervailing force of socialstructing is connecting

us at levels never seen before, opening up new

opportunities to create, learn, and share.

The following graph, from a 2011 report from the International Data Corporation, projects trends in digital information use to 2015 (E = Estimated).

Q. The passage’s discussion of life in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s primarily serves to

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material:

This passage is adapted from Marina Gorbis, The Nature of the Future: Dispatches from the Socialstructed World. ©2013 by Marina Gorbis.

Visitors to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and

1970s always marveled at the gap between what they

saw in state stores—shelves empty or filled with

things no one wanted—and what they saw in

(5) people’s homes: nice furnishings and tables filled