OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 10 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 10

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. Which choice best describes a major theme of the passage?

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. As compared with Silas’s gold, Eppie is portrayed as having more

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. Which statement best describes a technique the narrator uses to represent Silas’s character before he adopted Eppie?

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. The narrator uses the phrase “making trial of everything” (line 7) to present Eppie as

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. According to the narrator, one consequence of Silas adopting Eppie is that he

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. What function does the second paragraph (lines 30-52) serve in the passage as a whole?

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. In describing the relationship between Eppie and Silas, the narrator draws a connection between Eppie’s

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage.

This passage is adapted from George Eliot, Silas Marner. Originally published in 1861. Silas was a weaver and a notorious miser, but then the gold he had hoarded was stolen. Shortly after, Silas adopted a young child, Eppie, the daughter of an impoverished woman who had died suddenly.

Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must

be worshipped in close-locked solitude—which was

hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song

of birds, and started to no human tones—Eppie was a

(5) creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires,

seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and

living movements; making trial of everything, with

trust in new joy, and stirring the human kindness in

all eyes that looked on her. The gold had kept his

(10) thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to

nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object

compacted of changes and hopes that forced his

thoughts onward, and carried them far away from

their old eager pacing towards the same blank

(15) limit—carried them away to the new things that

would come with the coming years, when Eppie

would have learned to understand how her father

Silas cared for her; and made him look for images of

that time in the ties and charities that bound together

(20) the families of his neighbors. The gold had asked that

he should sit weaving longer and longer, deafened

and blinded more and more to all things except the

monotony of his loom and the repetition of his web;

but Eppie called him away from his weaving, and

(25) made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening

his senses with her fresh life, even to the old

winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early

spring sunshine, and warming him into joy because

she had joy.

(30) And when the sunshine grew strong and lasting,

so that the buttercups were thick in the meadows,

Silas might be seen in the sunny mid-day, or in the

late afternoon when the shadows were lengthening

under the hedgerows, strolling out with uncovered

(35) head to carry Eppie beyond the Stone-pits to where

the flowers grew, till they reached some favorite bank

where he could sit down, while Eppie toddled to

pluck the flowers, and make remarks to the winged

things that murmured happily above the bright

(40) petals, calling “Dad-dad’s” attention continually by

bringing him the flowers. Then she would turn her

ear to some sudden bird-note, and Silas learned to

please her by making signs of hushed stillness, that

they might listen for the note to come again: so that

(45) when it came, she set up her small back and laughed

with gurgling triumph. Sitting on the banks in this

way, Silas began to look for the once familiar herbs

again; and as the leaves, with their unchanged outline

and markings, lay on his palm, there was a sense of

(50) crowding remembrances from which he turned away

timidly, taking refuge in Eppie’s little world, that lay

lightly on his enfeebled spirit.

As the child’s mind was growing into knowledge,

his mind was growing into memory: as her life

(55) unfolded, his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow

prison, was unfolding too, and trembling gradually

into full consciousness.

It was an influence which must gather force with

every new year: the tones that stirred Silas’ heart

(60) grew articulate, and called for more distinct answers;

shapes and sounds grew clearer for Eppie’s eyes and

ears, and there was more that “Dad-dad” was

imperatively required to notice and account for.

Also, by the time Eppie was three years old, she

(65) developed a fine capacity for mischief, and for

devising ingenious ways of being troublesome, which

found much exercise, not only for Silas’ patience, but

for his watchfulness and penetration. Sorely was poor

Silas puzzled on such occasions by the incompatible

(70) demands of love.

Q. As used in line 65, “fine” most nearly means

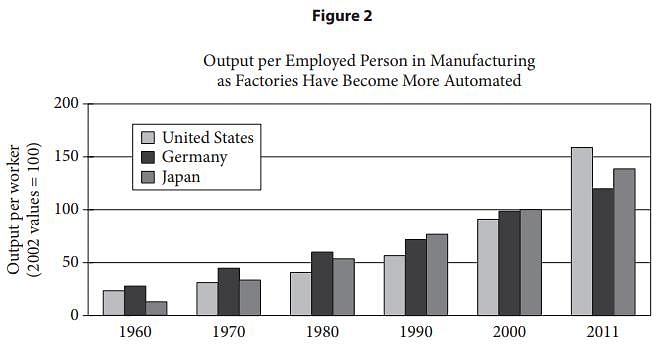

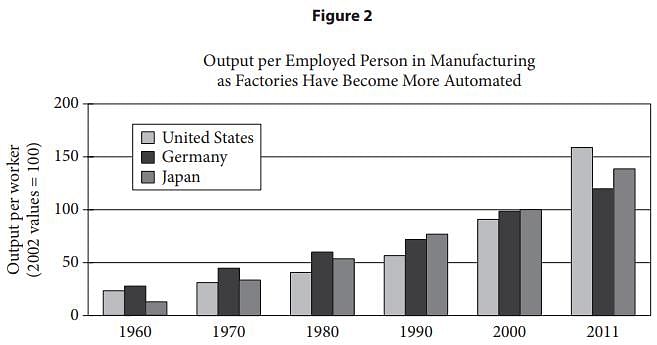

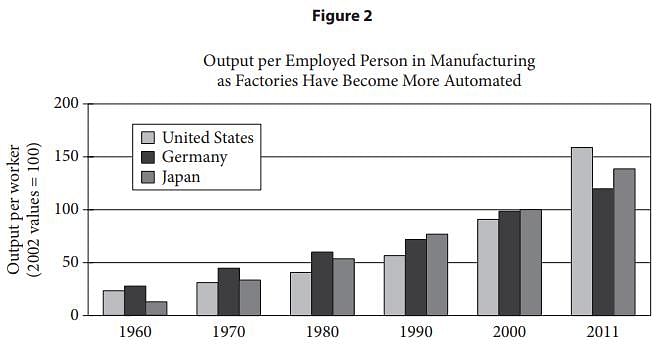

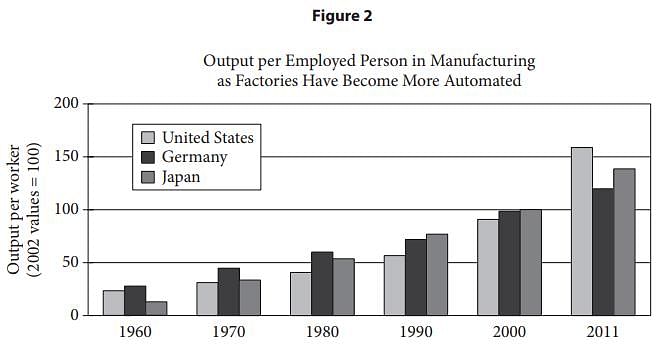

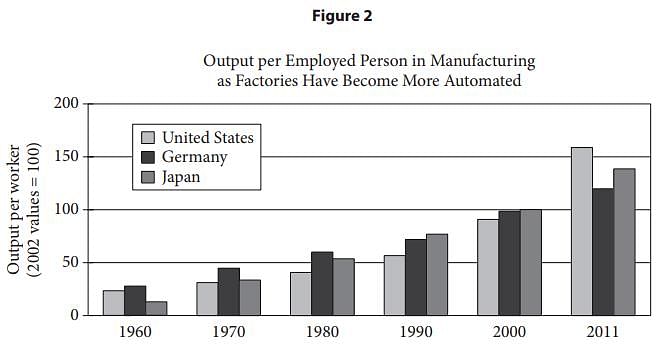

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by MIT Technology Review.

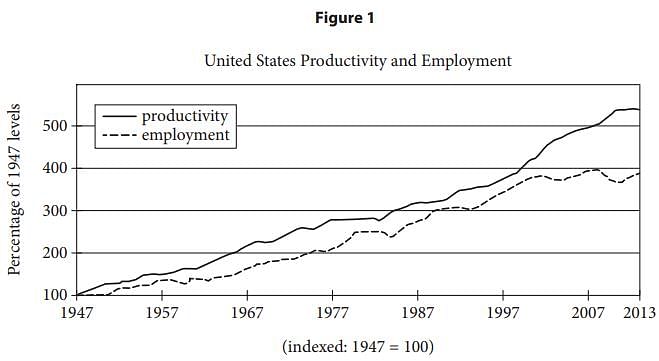

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

(5) services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

(10) in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

(15) in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent. But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

(20) stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

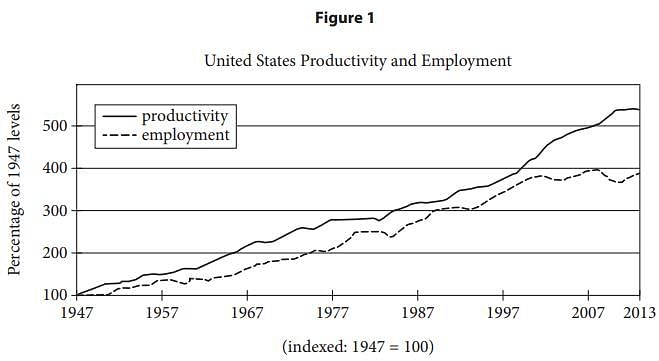

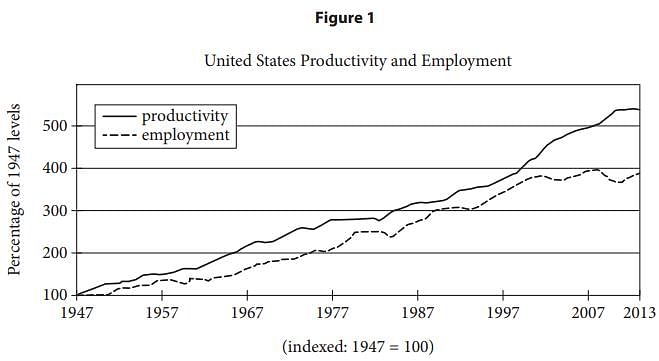

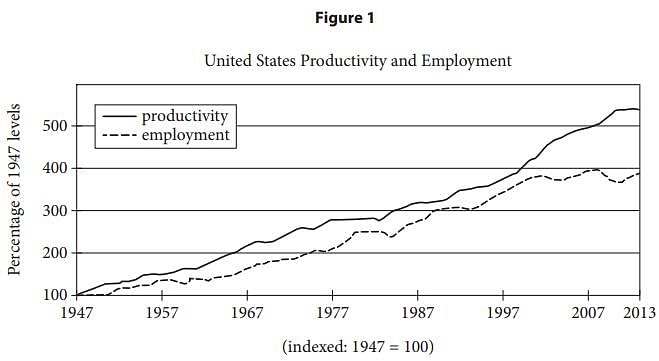

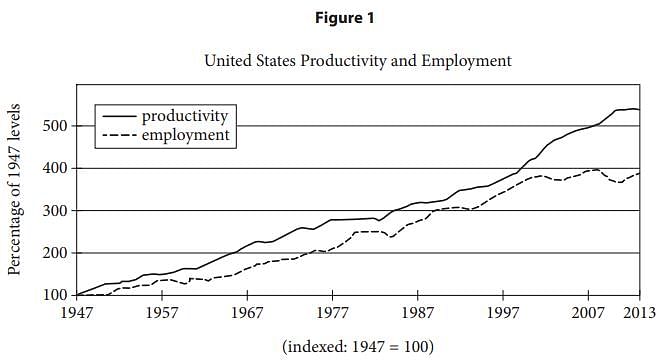

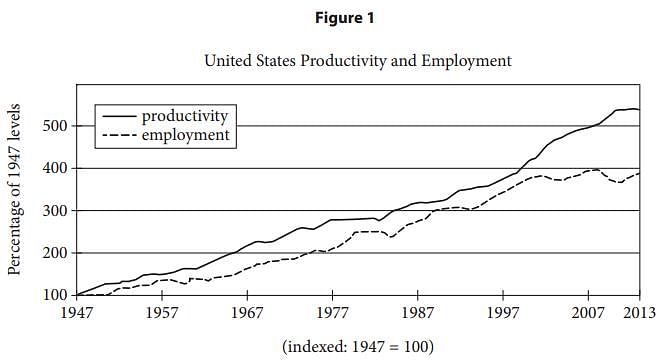

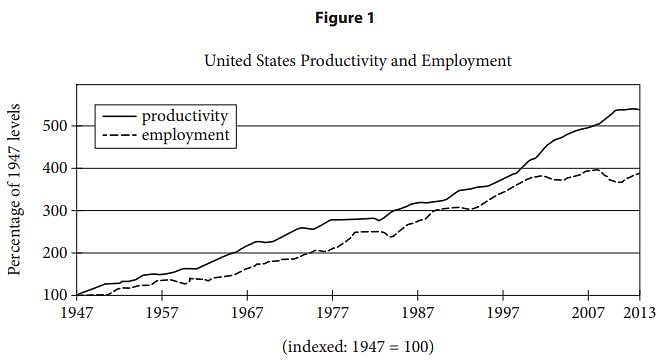

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

(25) chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

(30) chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the

two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in

jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The

(35) pattern is clear: as businesses generated more value

from their workers, the country as a whole became

richer, which fueled more economic activity and

created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the

lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly,

(40) but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a

significant gap appears between the two lines,

showing economic growth with no parallel increase

in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the

“great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is

(45) confident that technology is behind both the healthy

growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

It’s a startling assertion because it threatens the

faith that many economists place in technological

progress. Brynjolfsson and McAfee still believe that

(50) technology boosts productivity and makes societies

wealthier, but they think that it can also have a dark

side: technological progress is eliminating the need

for many types of jobs and leaving the typical worker

worse off than before. Brynjolfsson can point to a

(55) second chart indicating that median income is failing

to rise even as the gross domestic product soars. “It’s

the great paradox of our era,” he says. “Productivity

is at record levels, innovation has never been faster,

and yet at the same time, we have a falling median

(60) income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling

behind because technology is advancing so fast and

our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

While technological changes can be painful for

workers whose skills no longer match the needs of

(65) employers, Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist,

says that no historical pattern shows these shifts

leading to a net decrease in jobs over an extended

period. Katz has done extensive research on how

technological advances have affected jobs over the

(70) last few centuries—describing, for example, how

highly skilled artisans in the mid-19th century were

displaced by lower-skilled workers in factories.

While it can take decades for workers to acquire the

expertise needed for new types of employment, he

(75) says, “we never have run out of jobs. There is no

long-term trend of eliminating work for people. Over

the long term, employment rates are fairly

stable. People have always been able to create new

jobs. People come up with new things to do.”

(80) Still, Katz doesn’t dismiss the notion that there is

something different about today’s digital

technologies—something that could affect an even

broader range of work. The question, he says, is

whether economic history will serve as a useful

(85) guide. Will the job disruptions caused by technology

be temporary as the workforce adapts, or will we see

a science-fiction scenario in which automated

processes and robots with superhuman skills take

over a broad swath of human tasks? Though Katz

(90) expects the historical pattern to hold, it is “genuinely

a question,” he says. “If technology disrupts enough,

who knows what will happen?”

Q. The main purpose of the passage is to

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by MIT Technology Review.

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

(5) services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

(10) in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

(15) in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent. But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

(20) stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

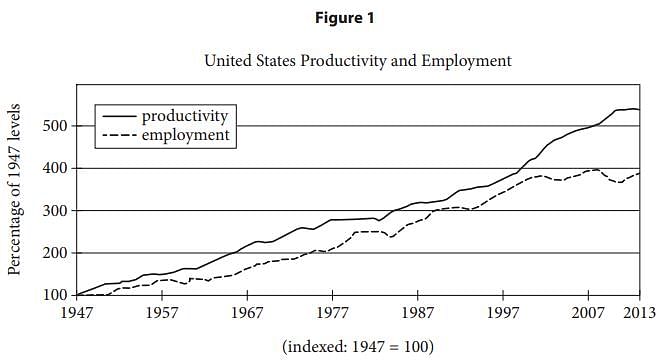

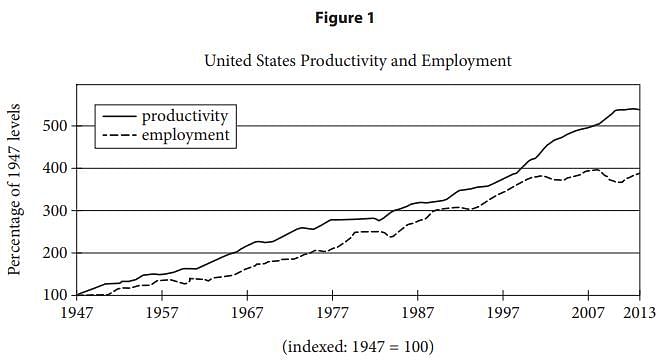

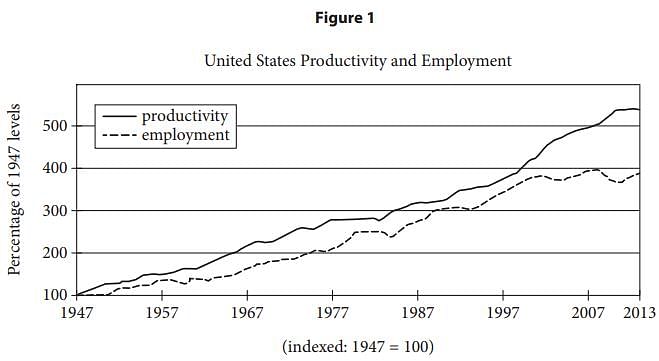

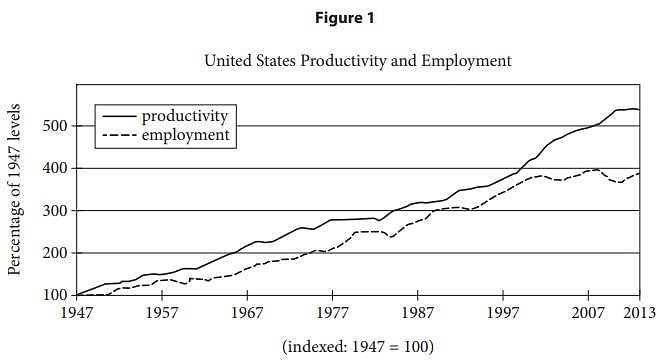

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

(25) chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

(30) chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the

two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in

jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The

(35) pattern is clear: as businesses generated more value

from their workers, the country as a whole became

richer, which fueled more economic activity and

created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the

lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly,

(40) but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a

significant gap appears between the two lines,

showing economic growth with no parallel increase

in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the

“great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is

(45) confident that technology is behind both the healthy

growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

It’s a startling assertion because it threatens the

faith that many economists place in technological

progress. Brynjolfsson and McAfee still believe that

(50) technology boosts productivity and makes societies

wealthier, but they think that it can also have a dark

side: technological progress is eliminating the need

for many types of jobs and leaving the typical worker

worse off than before. Brynjolfsson can point to a

(55) second chart indicating that median income is failing

to rise even as the gross domestic product soars. “It’s

the great paradox of our era,” he says. “Productivity

is at record levels, innovation has never been faster,

and yet at the same time, we have a falling median

(60) income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling

behind because technology is advancing so fast and

our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

While technological changes can be painful for

workers whose skills no longer match the needs of

(65) employers, Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist,

says that no historical pattern shows these shifts

leading to a net decrease in jobs over an extended

period. Katz has done extensive research on how

technological advances have affected jobs over the

(70) last few centuries—describing, for example, how

highly skilled artisans in the mid-19th century were

displaced by lower-skilled workers in factories.

While it can take decades for workers to acquire the

expertise needed for new types of employment, he

(75) says, “we never have run out of jobs. There is no

long-term trend of eliminating work for people. Over

the long term, employment rates are fairly

stable. People have always been able to create new

jobs. People come up with new things to do.”

(80) Still, Katz doesn’t dismiss the notion that there is

something different about today’s digital

technologies—something that could affect an even

broader range of work. The question, he says, is

whether economic history will serve as a useful

(85) guide. Will the job disruptions caused by technology

be temporary as the workforce adapts, or will we see

a science-fiction scenario in which automated

processes and robots with superhuman skills take

over a broad swath of human tasks? Though Katz

(90) expects the historical pattern to hold, it is “genuinely

a question,” he says. “If technology disrupts enough,

who knows what will happen?”

Q. According to Brynjolfsson and McAfee, advancements in technology since approximately the year 2000 have resulted in

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by MIT TechnologyReview.

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

(5) services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

(10) in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

(15) in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent. But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

(20) stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

(25) chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

(30) chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the

two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in

jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The

(35) pattern is clear: as businesses generated more value

from their workers, the country as a whole became

richer, which fueled more economic activity and

created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the

lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly,

(40) but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a

significant gap appears between the two lines,

showing economic growth with no parallel increase

in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the

“great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is

(45) confident that technology is behind both the healthy

growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

It’s a startling assertion because it threatens the

faith that many economists place in technological

progress. Brynjolfsson and McAfee still believe that

(50) technology boosts productivity and makes societies

wealthier, but they think that it can also have a dark

side: technological progress is eliminating the need

for many types of jobs and leaving the typical worker

worse off than before. Brynjolfsson can point to a

(55) second chart indicating that median income is failing

to rise even as the gross domestic product soars. “It’s

the great paradox of our era,” he says. “Productivity

is at record levels, innovation has never been faster,

and yet at the same time, we have a falling median

(60) income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling

behind because technology is advancing so fast and

our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

While technological changes can be painful for

workers whose skills no longer match the needs of

(65) employers, Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist,

says that no historical pattern shows these shifts

leading to a net decrease in jobs over an extended

period. Katz has done extensive research on how

technological advances have affected jobs over the

(70) last few centuries—describing, for example, how

highly skilled artisans in the mid-19th century were

displaced by lower-skilled workers in factories.

While it can take decades for workers to acquire the

expertise needed for new types of employment, he

(75) says, “we never have run out of jobs. There is no

long-term trend of eliminating work for people. Over

the long term, employment rates are fairly

stable. People have always been able to create new

jobs. People come up with new things to do.”

(80) Still, Katz doesn’t dismiss the notion that there is

something different about today’s digital

technologies—something that could affect an even

broader range of work. The question, he says, is

whether economic history will serve as a useful

(85) guide. Will the job disruptions caused by technology

be temporary as the workforce adapts, or will we see

a science-fiction scenario in which automated

processes and robots with superhuman skills take

over a broad swath of human tasks? Though Katz

(90) expects the historical pattern to hold, it is “genuinely

a question,” he says. “If technology disrupts enough,

who knows what will happen?”

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by MIT TechnologyReview.

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

(5) services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

(10) in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

(15) in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent. But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

(20) stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

(25) chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

(30) chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the

two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in

jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The

(35) pattern is clear: as businesses generated more value

from their workers, the country as a whole became

richer, which fueled more economic activity and

created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the

lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly,

(40) but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a

significant gap appears between the two lines,

showing economic growth with no parallel increase

in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the

“great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is

(45) confident that technology is behind both the healthy

growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

It’s a startling assertion because it threatens the

faith that many economists place in technological

progress. Brynjolfsson and McAfee still believe that

(50) technology boosts productivity and makes societies

wealthier, but they think that it can also have a dark

side: technological progress is eliminating the need

for many types of jobs and leaving the typical worker

worse off than before. Brynjolfsson can point to a

(55) second chart indicating that median income is failing

to rise even as the gross domestic product soars. “It’s

the great paradox of our era,” he says. “Productivity

is at record levels, innovation has never been faster,

and yet at the same time, we have a falling median

(60) income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling

behind because technology is advancing so fast and

our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

While technological changes can be painful for

workers whose skills no longer match the needs of

(65) employers, Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist,

says that no historical pattern shows these shifts

leading to a net decrease in jobs over an extended

period. Katz has done extensive research on how

technological advances have affected jobs over the

(70) last few centuries—describing, for example, how

highly skilled artisans in the mid-19th century were

displaced by lower-skilled workers in factories.

While it can take decades for workers to acquire the

expertise needed for new types of employment, he

(75) says, “we never have run out of jobs. There is no

long-term trend of eliminating work for people. Over

the long term, employment rates are fairly

stable. People have always been able to create new

jobs. People come up with new things to do.”

(80) Still, Katz doesn’t dismiss the notion that there is

something different about today’s digital

technologies—something that could affect an even

broader range of work. The question, he says, is

whether economic history will serve as a useful

(85) guide. Will the job disruptions caused by technology

be temporary as the workforce adapts, or will we see

a science-fiction scenario in which automated

processes and robots with superhuman skills take

over a broad swath of human tasks? Though Katz

(90) expects the historical pattern to hold, it is “genuinely

a question,” he says. “If technology disrupts enough,

who knows what will happen?”

Q. The primary purpose of lines 26-28 (“the amount... labor”) is to

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by MIT TechnologyReview.

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

(5) services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years. Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

(10) in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

(15) in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent. But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

(20) stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

(25) chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

(30) chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the