OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 4 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 4

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. The first two sentences of Passage 1 serve primarily to

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. The repetition of the phrase “not all” in lines 15 and 16 emphasizes the author’s point that the “debaters” (line 13) tend to

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. The phrase “life cycles” (line 22) refers most directly to the

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. In line 50, “inserting” most nearly means

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. Which choice would the author of Passage 2 consider to be a direct effect of “natural ecosystems” (line 58)?

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. Which of the following policies would most likely be endorsed by the author of Passage 1?

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

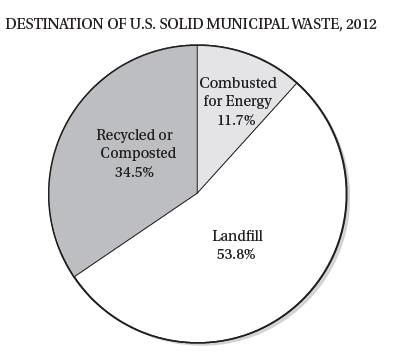

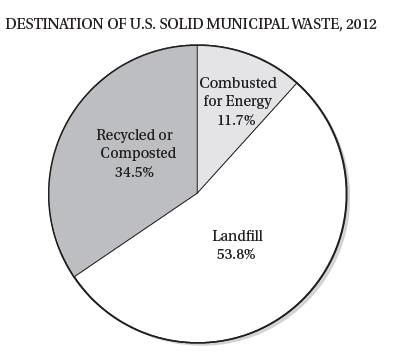

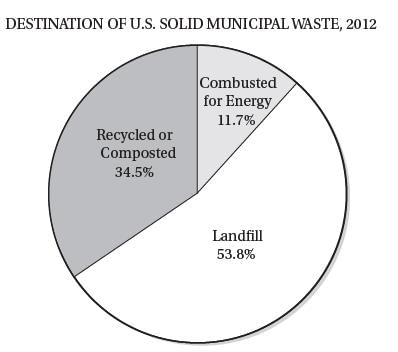

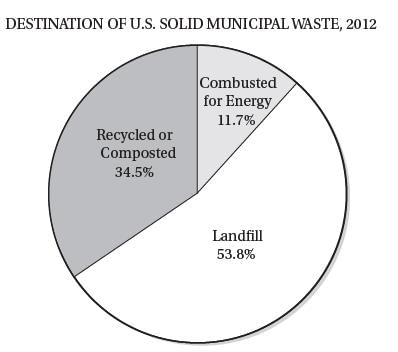

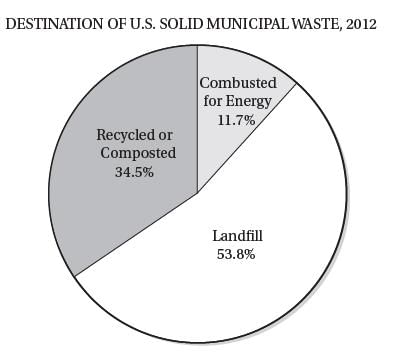

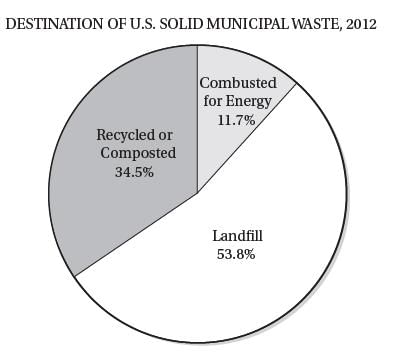

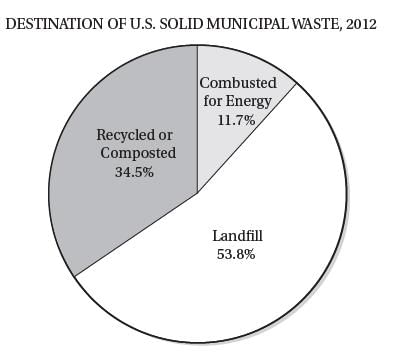

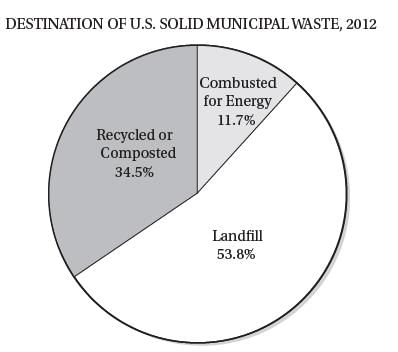

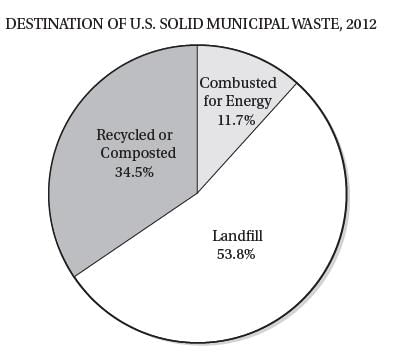

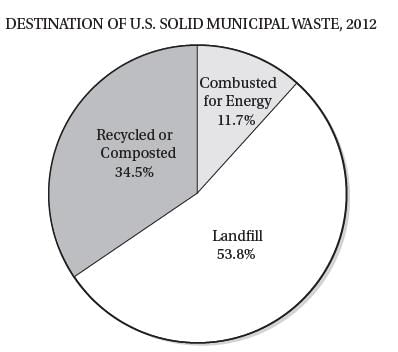

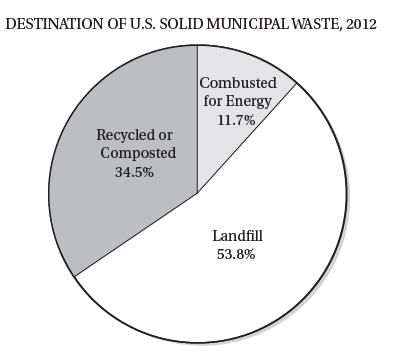

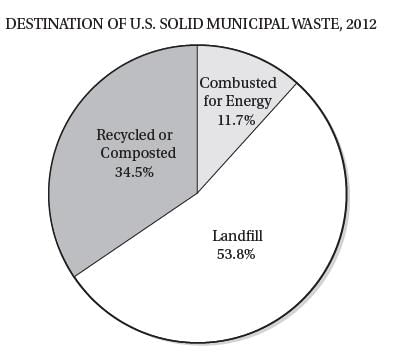

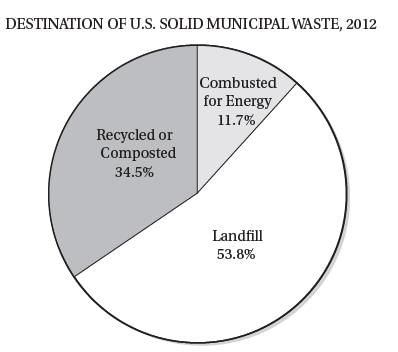

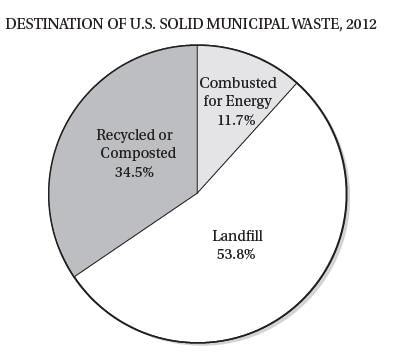

Q. The diagram provides information most relevant to

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.

(65) The diffuse, unchosen costs and benefits that

affect all of us daily—annoying commercials or a

beautiful sunset, for instance—are much harder

to evaluate.

The benefits that ecosystems provide, like

(70) biodiversity, the filtration of groundwater, the

maintenance of the oxygen and nitrogen cycles,

and climate stability, however, are not bought-

and-sold commodities. Without them our lives

would deteriorate dramatically, but they are

(75) not part of a clear exchange, so they fall into the

class of benefits and costs that economists call

“externalities.”

The “good feeling” that many people have

about recycling and maintaining environmental

(80) quality is just such an externality. Anti

environmentalists often ridicule such feelings

as unquantifiable, but their value is real: some

stock funds only invest in companies with good

environmental records, and environmental

(85) litigation can have steep costs in terms of money

and goodwill.

Robert Costanza, formerly of the Center

for Environmental Science at the University

of Maryland, has attempted to quantify these

(90) “external” ecological benefits by tallying the

cost to replace nature's services. Imagine, for

instance, paving over the Florida Everglades and

then building systems to restore its lost benefits,

such as gas conversion and sequestering,

(95) food production, water filtration, and weather

regulation. How much would it cost to keep these

systems running? Not even accounting for some

of the most important externalities, like natural

beauty, the cost would be extraordinarily high.

(100) Costanza places it “conservatively” at $33 trillion

dollars annually, far more than the economic

output of all of the countries in the world.

Some object to Costanza's cost analysis.

Environmentalists argue that we cannot possibly

(105) put a price on the smell of heather and a cool

breeze, while industrialists argue that the task

is speculative, unreliable, and an impediment

to economic progress. Nevertheless, Costanza's

work is among the most cited in the fields of

(110) environmental science and economics. For

any flaws it might have, his work is giving a

common vocabulary to industrialists and

environmentalists alike, which we must do if

we are to coordinate intelligent environmental

(115) policy with responsible economic policy.

Q. Which choice best exemplifies the “clear exchange” (line 75) mentioned in Passage 2?

Question are based on the following passages and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is from F. J. Medina, “How to Talk about Sustainability." ©2015 College Hill Coaching. Passage 2 is adapted from an essay published in 2005 about the economic analysis of environmental decisions.

Passage 1

Many proponents of recycling assume that

recycling industrial, domestic, and commercial

materials does less harm to the environment than

does extracting new raw materials. Opponents, on

(5) the other hand, scrutinize the costs of recycling,

arguing that recycling programs often waste more

money than they save, and that companies can

often produce new products more cheaply than

they can recycle old ones. The discussion usually

(10) devolves into a political battle between the

enemies of the economy and the enemies of the

environment.

This demonization serves the debaters

(and their fundraisers) but not the debate.

(15) Environmentalists are not all ignorant anarchists,

and opponents of recycling are not all rapacious

blowhards. For real solutions, we must soberly

compare the many costs and benefits of recycling

with the many costs and benefits of disposal, as

(20) if we are all stewards of both the earth and the

economy.

We must examine the full life cycles of

various materials, and the broad effects these

cycles have on both the environment and

(25) economy. When debating the cost of a new

road, for instance, it is not enough to simply

consider the cost of the labor or the provenance

of the materials. We must ask, what natural

benefits, like water filtration and animal and

(30) plant habitats, are being lost in the construction?

Where will the road materials be in a hundred

years, and what will they be doing? What kinds

of industries will the road construction and

maintenance support? How will the extra traffic

(35) affect air and noise quality, or safety? Is the road

made of local or imported materials? Are any

materials being imported from countries with

irresponsible labor or environmental practices?

Is the contractor chosen through a fair and open

(40) bidding process? How might the road surface

affect the life span or efficiency of the cars driving

on it? What will be the annual maintenance cost,

financially and environmentally?

Appreciating opposing viewpoints can lead

(45) to important insights. Perhaps nature can do

a more efficient and safer job of reusing waste

matter than a recycling plant can. Perhaps an

economic system that accounts for environmental

costs and benefits will lead to a higher standard

(50) of living for the average citizen. Perhaps inserting

some natural resources into a responsible

“industrial cycle” is better for the environment

than conserving those resources. Exploring such

possibilities openly and respectfully will lead us

(55) more reliably to both a healthier economy and a

healthier environment.

Passage 2

When trying to quantify the costs and

benefits of preserving our natural ecosystems,

one difficulty lies in the diffuseness of these

(60) effects. Economists have a relatively easy time

with commerce, because money and goods can

be tracked through a series of point-to-point

exchanges. When you pay for something, the

exchange of money makes the accounting simple.