OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 6 - SAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - OneTime: Digital SAT Mock Test - 6

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

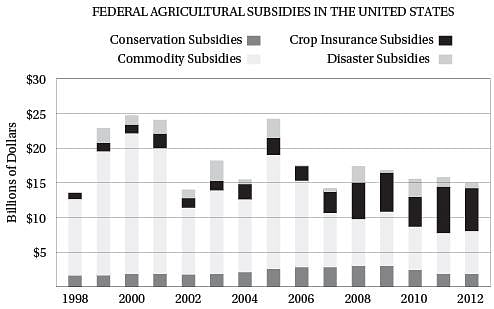

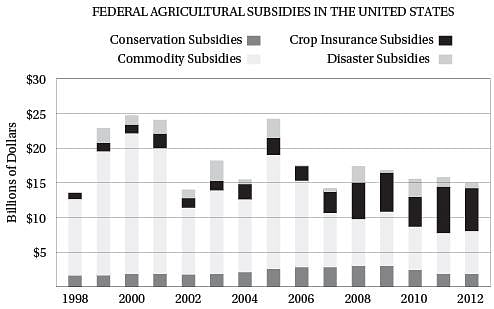

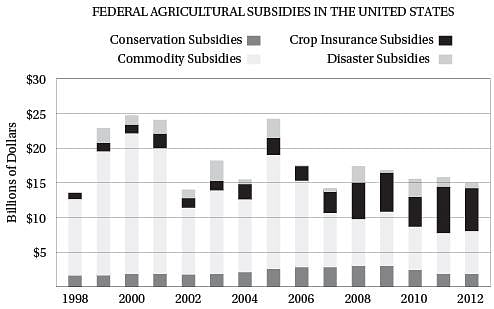

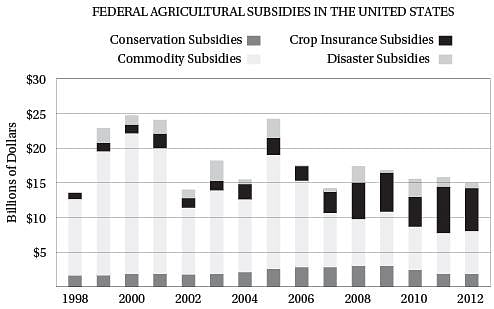

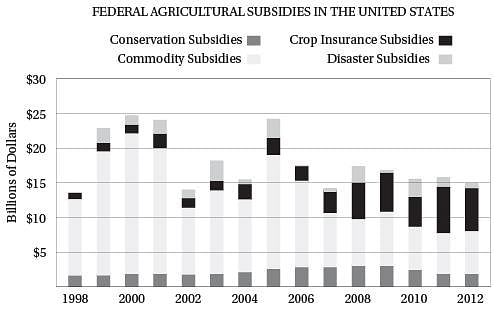

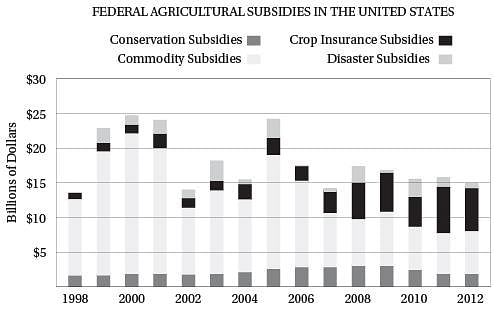

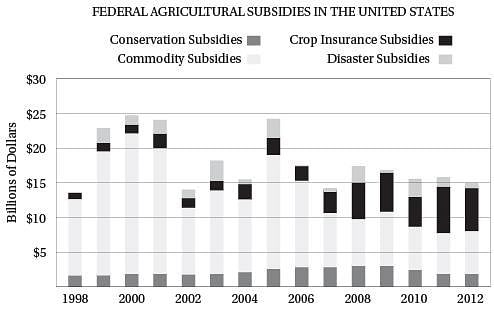

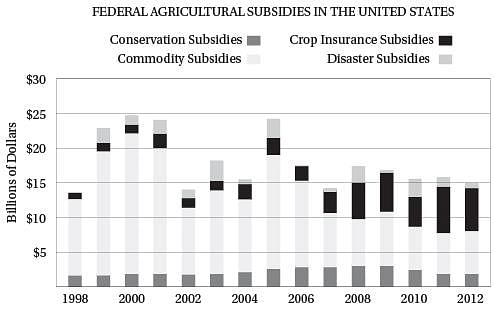

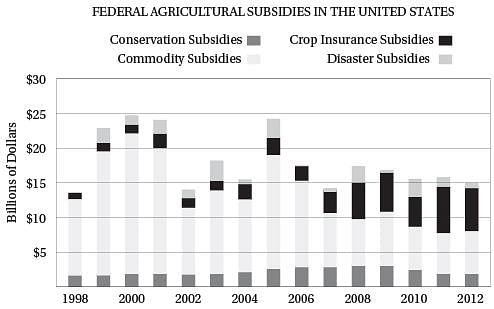

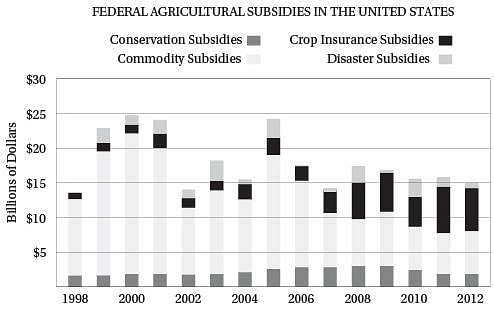

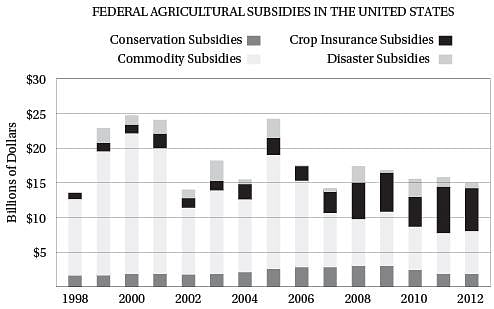

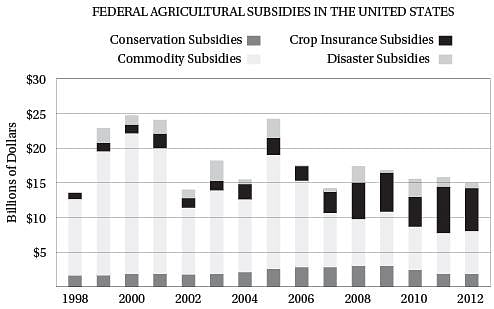

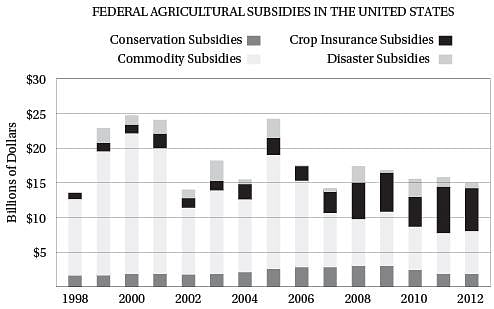

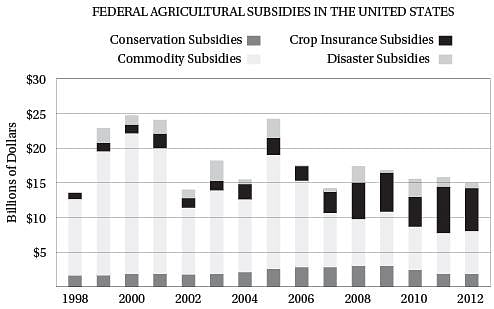

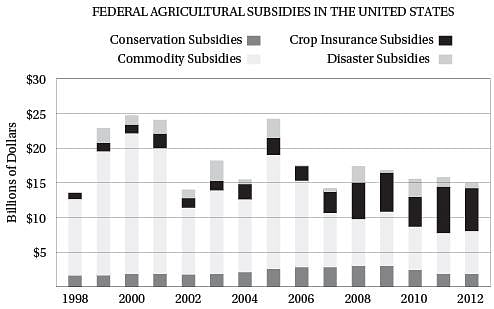

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. Both passages acknowledge the effectiveness of U.S. farm subsidies in

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. The first sentence of Passage 1 refers primarily to the author’s belief that

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. The author of Passage 2 would most likely regard the “taxes” mentioned in line 15 as

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. The author of Passage 1 believes that the GAO report “probably won’t” (line 9) horrify lawmakers because

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. Which of the following provides the strongest evidence for the answer to the previous question?

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. Unlike Passage 1, Passage 2 emphasizes the danger of

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. Passage 1 mentions the results of the 2009 poll (lines 42–45) primarily to

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. If the author of Passage 1 were to use the data in the graph to support his main thesis, he would most likely mention

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.

American farmers receive an average of just 20% of

their incomes from subsidies, compared to 70% for

farmers from some other countries. The European

(95) Union spends about five times what the United

States spends on farm subsidies, amounting to

45% of the EU budget, compared to less than 1%

of the U.S. federal budget. Although the U.S. farm

subsidies programs are not perfect, they provide

(100) enormous benefits not only to farms but also

to associated industries employing millions of

people and to nearly every American consumer.

Q. If the author of Passage 2 were to use the data in the graph to support his main thesis, he would most likely mention

Question are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Passage 1 is adapted from Nicholas Heidorn, “The Enduring Political Illusion of Farm Subsidies.” ©2004 The Independent Institute. Originally Published August 18, 2004 in the San Francisco Chronicle. Passage 2 is ©2015 by Mark Anestis. Since 1922, the U.S. government has subsidized the agricultural industry by supporting the price of crops (commodity subsidies), paying farmers let their fields go fallow (conservation subsidies), helping farmers purchase crop insurance (crop insurance subsidies), and compensating farmers for uninsured losses due to disasters (disaster subsidies). The following passages discuss these programs.

Passage 1

Something is rotten down on the farm. A recent

General Accounting Office study found that the

U.S. farm subsidy program, a multibillion-dollar

system of direct payments to American farmers,

(5) uses administrators who are ill-trained and

poorly monitored, and who give away millions

of taxpayer dollars to farmers who are actually

ineligible for the program. This report should

horrify lawmakers, but it probably won’t.

(10) From 1995 to 2002, the United States Congress

doled out more than $114 billion to farmers. Why?

One misconception is that subsidies are

a boon to consumers because they lower food

prices. This ignores the fact that consumers are

(15) also paying for these subsidies through taxes.

Because of inefficiencies in the program, we

taxpayers will pay more in taxes than we will ever

get back in lower corn or wheat prices.

In fact, farm subsidies are not even intended

(20) to reduce food prices significantly. When prices

are too low, farmers lose money. To prevent this

situation, Congress also pays farmers additional

“conservation subsidies” to leave their land fallow,

thereby lowering supply and boosting prices again.

(25) We’re taxed to lower prices, and then taxed to raise them again.

Another myth is that subsidies increase

exports, and thereby benefit the American

economy, by lowering the price of farm products

(30) and so making them more attractive to foreign

consumers. This ignores two realities. First,

farm subsidies transfer wealth from taxpayers

to foreign consumers just as efficiently as

they transfer wealth to domestic consumers.

(35) Second, farm subsidies are actually harming

American exporters. In March 2005, the World

Trade Organization ruled that American cotton

subsidies violated global free-trade rules, which

could lead to billions of dollars in retaliatory

(40) tariffs or penalties.

The worst misconception is that we need these

subsidies to save the small family farmer. Indeed,

according to a 2009 poll, about 77 percent of

Americans support giving subsidies to small family

(45) farms. But according to the Environmental Working

Group, 71 percent of farm subsidies go to the top

10 percent of beneficiaries, almost all of which are

large corporate farms. By subsidizing these rich

farmers, we actually make it much harder for the

(50) small family farmers to compete, not to mention

the millions of impoverished third world farmers

who rely on farming for their livelihood.

Rich corporate farmers are an enormously

powerful lobby in American politics. Agribusines

(55) and farm insurance lobbies pump nearly $100

million into political campaigns every year, and

the floodgates show no sign of closing. So don’t be

surprised if the GAO’s reports of mismanagement

and waste go unheeded. Politicians like their

(60) payouts almost as much as the big farmers and

their insurance companies do.

Passage 2

The critics of the U.S. farm subsidy program fail

to recognize just how vital these subsidies really

are. They are not as burdensome to American

(65) taxpayers as the critics claim, and indeed provide

important benefits. By protecting farmers from

damaging fluctuations in commodity prices due

to weather disasters or market disruptions, these

subsidies help sustain a vital American industry.

(70) At the same time, they protect consumers from

price spikes that can accompany steep drops in

crop inventories. Before price supports became

common in the 20th century, crop failures

devastated the lives of farmers and consumers with

(75) horrifying frequency.

Opponents say that subsidies distort the

free market and create surpluses in supply. But

halting subsidies would allow regular shortfalls,

which are far more damaging. The year-to-year

(80) carryover of these surpluses protects farmers

from low prices and consumers from high prices.

Another misconception is that subsidies

only benefit the producers. In fact, they help

many related industries as well, including food

(85) processing, distribution, and marketing, chiefly

by helping to lower the cost of production. And,

of course, the consumers receive the benefit of

lower prices.

When assessing the costs and benefits of

(90) farm payments, it is important to compare these

subsidies to those of other industrialized nations.