XAT Mock Test - 9 (New Pattern) - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - XAT Mock Test - 9 (New Pattern)

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

Imagine that we stand on any ordinary seaside pier, and watch the waves rolling in and striking against the iron columns of the pier. Large waves pay very little attention to the columns—they divide right and left and re-unite after passing each column, much as a regiment of soldiers would if a tree stood in their way; it is almost as though the columns had not been there. But the short waves and ripples find the columns of the pier a much more formidable obstacle. When the short waves impinge on the columns, they are reflected back and spread as new ripples in all directions. To use the technical term, they are “scattered.” The obstacle provided by the iron columns hardly affects the long waves at all, but scatters the short ripples.

We have been watching a working model of the way in which sunlight struggles through the earth’s atmosphere. Between us on earth and outer space the atmosphere interposes innumerable obstacles in the form of molecules of air, tiny droplets of water, and small particles of dust. They are represented by the columns of the pier.

The waves of the sea represent the sunlight. We know that sunlight is a blend of lights of many colors—as we can prove for ourselves by passing it through a prism, or even through a jug of water, or as Nature demonstrates to us when she passes it through the raindrops of a summer shower and produces a rainbow. We also know that light consists of waves, and that the different colors of light are produced by waves of different lengths, red light by long waves and blue light by short waves. The mixture of waves which constitutes sunlight has to struggle through the obstacles it meets in the atmosphere, just as the mixture of waves at the seaside has to struggle past the columns of the pier. And these obstacles treat the light waves much as the columns of the pier treat the sea-waves. The long waves which constitute red light are hardly affected, but the short waves which constitute blue light are scattered in all directions.

Thus, the different constituents of sunlight are treated in different ways as they struggle through the earth’s atmosphere. A wave of blue light may be scattered by a dust particle, and turned out of its course. After a time a second dust particle again turns it out of its course, and so on, until finally it enters our eyes by a path as zigzag as that of a flash of lightning. Consequently, the blue waves of the sunlight enter our eyes from all directions. And that is why the sky looks blue.

We know from experience that if we look directly at the sun, we will see red light near the sun. This observation is supported by the passage for which one of the following reasons?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

Imagine that we stand on any ordinary seaside pier, and watch the waves rolling in and striking against the iron columns of the pier. Large waves pay very little attention to the columns—they divide right and left and re-unite after passing each column, much as a regiment of soldiers would if a tree stood in their way; it is almost as though the columns had not been there. But the short waves and ripples find the columns of the pier a much more formidable obstacle. When the short waves impinge on the columns, they are reflected back and spread as new ripples in all directions. To use the technical term, they are “scattered.” The obstacle provided by the iron columns hardly affects the long waves at all, but scatters the short ripples.

We have been watching a working model of the way in which sunlight struggles through the earth’s atmosphere. Between us on earth and outer space the atmosphere interposes innumerable obstacles in the form of molecules of air, tiny droplets of water, and small particles of dust. They are represented by the columns of the pier.

The waves of the sea represent the sunlight. We know that sunlight is a blend of lights of many colors—as we can prove for ourselves by passing it through a prism, or even through a jug of water, or as Nature demonstrates to us when she passes it through the raindrops of a summer shower and produces a rainbow. We also know that light consists of waves, and that the different colors of light are produced by waves of different lengths, red light by long waves and blue light by short waves. The mixture of waves which constitutes sunlight has to struggle through the obstacles it meets in the atmosphere, just as the mixture of waves at the seaside has to struggle past the columns of the pier. And these obstacles treat the light waves much as the columns of the pier treat the sea-waves. The long waves which constitute red light are hardly affected, but the short waves which constitute blue light are scattered in all directions.

Thus, the different constituents of sunlight are treated in different ways as they struggle through the earth’s atmosphere. A wave of blue light may be scattered by a dust particle, and turned out of its course. After a time a second dust particle again turns it out of its course, and so on, until finally it enters our eyes by a path as zigzag as that of a flash of lightning. Consequently, the blue waves of the sunlight enter our eyes from all directions. And that is why the sky looks blue.

Scientists have observed that shorter wavelength light has more energy than longer wavelength light. From this we can conclude that

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

Imagine that we stand on any ordinary seaside pier, and watch the waves rolling in and striking against the iron columns of the pier. Large waves pay very little attention to the columns—they divide right and left and re-unite after passing each column, much as a regiment of soldiers would if a tree stood in their way; it is almost as though the columns had not been there. But the short waves and ripples find the columns of the pier a much more formidable obstacle. When the short waves impinge on the columns, they are reflected back and spread as new ripples in all directions. To use the technical term, they are “scattered.” The obstacle provided by the iron columns hardly affects the long waves at all, but scatters the short ripples.

We have been watching a working model of the way in which sunlight struggles through the earth’s atmosphere. Between us on earth and outer space the atmosphere interposes innumerable obstacles in the form of molecules of air, tiny droplets of water, and small particles of dust. They are represented by the columns of the pier.

The waves of the sea represent the sunlight. We know that sunlight is a blend of lights of many colors—as we can prove for ourselves by passing it through a prism, or even through a jug of water, or as Nature demonstrates to us when she passes it through the raindrops of a summer shower and produces a rainbow. We also know that light consists of waves, and that the different colors of light are produced by waves of different lengths, red light by long waves and blue light by short waves. The mixture of waves which constitutes sunlight has to struggle through the obstacles it meets in the atmosphere, just as the mixture of waves at the seaside has to struggle past the columns of the pier. And these obstacles treat the light waves much as the columns of the pier treat the sea-waves. The long waves which constitute red light are hardly affected, but the short waves which constitute blue light are scattered in all directions.

Thus, the different constituents of sunlight are treated in different ways as they struggle through the earth’s atmosphere. A wave of blue light may be scattered by a dust particle, and turned out of its course. After a time a second dust particle again turns it out of its course, and so on, until finally it enters our eyes by a path as zigzag as that of a flash of lightning. Consequently, the blue waves of the sunlight enter our eyes from all directions. And that is why the sky looks blue.

From the information presented in the passage, what can we conclude about the color of the sky on a day with a large quantity of dust in the air?

Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions that follow.

Imagine that we stand on any ordinary seaside pier, and watch the waves rolling in and striking against the iron columns of the pier. Large waves pay very little attention to the columns—they divide right and left and re-unite after passing each column, much as a regiment of soldiers would if a tree stood in their way; it is almost as though the columns had not been there. But the short waves and ripples find the columns of the pier a much more formidable obstacle. When the short waves impinge on the columns, they are reflected back and spread as new ripples in all directions. To use the technical term, they are “scattered.” The obstacle provided by the iron columns hardly affects the long waves at all, but scatters the short ripples.

We have been watching a working model of the way in which sunlight struggles through the earth’s atmosphere. Between us on earth and outer space the atmosphere interposes innumerable obstacles in the form of molecules of air, tiny droplets of water, and small particles of dust. They are represented by the columns of the pier.

The waves of the sea represent the sunlight. We know that sunlight is a blend of lights of many colors—as we can prove for ourselves by passing it through a prism, or even through a jug of water, or as Nature demonstrates to us when she passes it through the raindrops of a summer shower and produces a rainbow. We also know that light consists of waves, and that the different colors of light are produced by waves of different lengths, red light by long waves and blue light by short waves. The mixture of waves which constitutes sunlight has to struggle through the obstacles it meets in the atmosphere, just as the mixture of waves at the seaside has to struggle past the columns of the pier. And these obstacles treat the light waves much as the columns of the pier treat the sea-waves. The long waves which constitute red light are hardly affected, but the short waves which constitute blue light are scattered in all directions.

Thus, the different constituents of sunlight are treated in different ways as they struggle through the earth’s atmosphere. A wave of blue light may be scattered by a dust particle, and turned out of its course. After a time a second dust particle again turns it out of its course, and so on, until finally it enters our eyes by a path as zigzag as that of a flash of lightning. Consequently, the blue waves of the sunlight enter our eyes from all directions. And that is why the sky looks blue.

Which one of the following does the author seem to imply?

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow:

To the superficial observer scientific truth is unassailable, the logic of science is infallible; and if scientific men sometimes make mistakes, it is because they have not understood the rules of the game. Mathematical truths are derived from a few self-evident propositions, by a chain of flawless reasonings; they are imposed not only on us, but on Nature itself. By them the Creator is fettered, as it were, and His choice is limited to a relatively small number of solutions. A few experiments, therefore, will be sufficient to enable us to determine what choice He has made. From each experiment a number of consequences will follow by a series of mathematical deductions, and in this way each of them will reveal to us a corner of the universe. This, to the minds of most people, and to students who are getting their first ideas of physics, is the origin of certainty in science. This is what they take to be the role of experiment and mathematics. And thus, too, it was understood a hundred years ago by many men of science who dreamed of constructing the world with the aid of the smallest possible amount of material borrowed from experiment.

But upon more mature reflection the position held by hypothesis was seen; it was recognised that it is as necessary to the experimenter as it is to the mathematician. And then the doubt arose if all these constructions are built on solid foundations. The conclusion was drawn that a breath would bring them to the ground. This sceptical attitude does not escape the charge of superficiality. To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

Instead of a summary condemnation we should examine with the utmost care the rôle of hypothesis; we shall then recognise not only that it is necessary, but that in most cases it is legitimate. We shall also see that there are several kinds of hypotheses; that some are verifiable, and when once confirmed by experiment become truths of great fertility; that others may be useful to us in fixing our ideas; and finally, that others are hypotheses only in appearance, and reduce to definitions or to conventions in disguise. The latter are to be met with especially in mathematics and in the sciences to which it is applied. From them, indeed, the sciences derive their rigour; such conventions are the result of the unrestricted activity of the mind, which in this domain recognizes no obstacle. For here the mind may affirm because it lays down its own laws; but let us clearly understand that while these laws are imposed on science, which otherwise could not exist, they are not imposed on Nature. Are they then arbitrary? No; for if they were, they would not be fertile. Experience leaves us our freedom of choice, but it guides us by helping us to discern the most convenient path to follow. Our laws are therefore like those of an absolute monarch, who is wise and consults his council of state.

In the sentence, “By them the Creator is fettered, as it were, and His choice is limited to a relatively small number of solutions”, the “them” refers to:

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow

To the superficial observer scientific truth is unassailable, the logic of science is infallible; and if scientific men sometimes make mistakes, it is because they have not understood the rules of the game. Mathematical truths are derived from a few self-evident propositions, by a chain of flawless reasonings; they are imposed not only on us, but on Nature itself. By them the Creator is fettered, as it were, and His choice is limited to a relatively small number of solutions. A few experiments, therefore, will be sufficient to enable us to determine what choice He has made. From each experiment a number of consequences will follow by a series of mathematical deductions, and in this way each of them will reveal to us a corner of the universe. This, to the minds of most people, and to students who are getting their first ideas of physics, is the origin of certainty in science. This is what they take to be the role of experiment and mathematics. And thus, too, it was understood a hundred years ago by many men of science who dreamed of constructing the world with the aid of the smallest possible amount of material borrowed from experiment.

But upon more mature reflection the position held by hypothesis was seen; it was recognised that it is as necessary to the experimenter as it is to the mathematician. And then the doubt arose if all these constructions are built on solid foundations. The conclusion was drawn that a breath would bring them to the ground. This sceptical attitude does not escape the charge of superficiality. To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

Instead of a summary condemnation we should examine with the utmost care the rôle of hypothesis; we shall then recognise not only that it is necessary, but that in most cases it is legitimate. We shall also see that there are several kinds of hypotheses; that some are verifiable, and when once confirmed by experiment become truths of great fertility; that others may be useful to us in fixing our ideas; and finally, that others are hypotheses only in appearance, and reduce to definitions or to conventions in disguise. The latter are to be met with especially in mathematics and in the sciences to which it is applied. From them, indeed, the sciences derive their rigour; such conventions are the result of the unrestricted activity of the mind, which in this domain recognizes no obstacle. For here the mind may affirm because it lays down its own laws; but let us clearly understand that while these laws are imposed on science, which otherwise could not exist, they are not imposed on Nature. Are they then arbitrary? No; for if they were, they would not be fertile. Experience leaves us our freedom of choice, but it guides us by helping us to discern the most convenient path to follow. Our laws are therefore like those of an absolute monarch, who is wise and consults his council of state.

When the author of the passage says, “The conclusion was drawn that a breath would bring them to the ground”, he essentially refers to:

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow

To the superficial observer scientific truth is unassailable, the logic of science is infallible; and if scientific men sometimes make mistakes, it is because they have not understood the rules of the game. Mathematical truths are derived from a few self-evident propositions, by a chain of flawless reasonings; they are imposed not only on us, but on Nature itself. By them the Creator is fettered, as it were, and His choice is limited to a relatively small number of solutions. A few experiments, therefore, will be sufficient to enable us to determine what choice He has made. From each experiment a number of consequences will follow by a series of mathematical deductions, and in this way each of them will reveal to us a corner of the universe. This, to the minds of most people, and to students who are getting their first ideas of physics, is the origin of certainty in science. This is what they take to be the role of experiment and mathematics. And thus, too, it was understood a hundred years ago by many men of science who dreamed of constructing the world with the aid of the smallest possible amount of material borrowed from experiment.

But upon more mature reflection the position held by hypothesis was seen; it was recognised that it is as necessary to the experimenter as it is to the mathematician. And then the doubt arose if all these constructions are built on solid foundations. The conclusion was drawn that a breath would bring them to the ground. This sceptical attitude does not escape the charge of superficiality. To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

Instead of a summary condemnation we should examine with the utmost care the rôle of hypothesis; we shall then recognise not only that it is necessary, but that in most cases it is legitimate. We shall also see that there are several kinds of hypotheses; that some are verifiable, and when once confirmed by experiment become truths of great fertility; that others may be useful to us in fixing our ideas; and finally, that others are hypotheses only in appearance, and reduce to definitions or to conventions in disguise. The latter are to be met with especially in mathematics and in the sciences to which it is applied. From them, indeed, the sciences derive their rigour; such conventions are the result of the unrestricted activity of the mind, which in this domain recognizes no obstacle. For here the mind may affirm because it lays down its own laws; but let us clearly understand that while these laws are imposed on science, which otherwise could not exist, they are not imposed on Nature. Are they then arbitrary? No; for if they were, they would not be fertile. Experience leaves us our freedom of choice, but it guides us by helping us to discern the most convenient path to follow. Our laws are therefore like those of an absolute monarch, who is wise and consults his council of state.

By comparing the laws laid down by our mind to those of an absolute monarch, the author is trying to:

Directions: Read the following passage and answer the questions that follow

To the superficial observer scientific truth is unassailable, the logic of science is infallible; and if scientific men sometimes make mistakes, it is because they have not understood the rules of the game. Mathematical truths are derived from a few self-evident propositions, by a chain of flawless reasonings; they are imposed not only on us, but on Nature itself. By them the Creator is fettered, as it were, and His choice is limited to a relatively small number of solutions. A few experiments, therefore, will be sufficient to enable us to determine what choice He has made. From each experiment a number of consequences will follow by a series of mathematical deductions, and in this way each of them will reveal to us a corner of the universe. This, to the minds of most people, and to students who are getting their first ideas of physics, is the origin of certainty in science. This is what they take to be the role of experiment and mathematics. And thus, too, it was understood a hundred years ago by many men of science who dreamed of constructing the world with the aid of the smallest possible amount of material borrowed from experiment.

But upon more mature reflection the position held by hypothesis was seen; it was recognised that it is as necessary to the experimenter as it is to the mathematician. And then the doubt arose if all these constructions are built on solid foundations. The conclusion was drawn that a breath would bring them to the ground. This sceptical attitude does not escape the charge of superficiality. To doubt everything or to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection.

Instead of a summary condemnation we should examine with the utmost care the rôle of hypothesis; we shall then recognise not only that it is necessary, but that in most cases it is legitimate. We shall also see that there are several kinds of hypotheses; that some are verifiable, and when once confirmed by experiment become truths of great fertility; that others may be useful to us in fixing our ideas; and finally, that others are hypotheses only in appearance, and reduce to definitions or to conventions in disguise. The latter are to be met with especially in mathematics and in the sciences to which it is applied. From them, indeed, the sciences derive their rigour; such conventions are the result of the unrestricted activity of the mind, which in this domain recognizes no obstacle. For here the mind may affirm because it lays down its own laws; but let us clearly understand that while these laws are imposed on science, which otherwise could not exist, they are not imposed on Nature. Are they then arbitrary? No; for if they were, they would not be fertile. Experience leaves us our freedom of choice, but it guides us by helping us to discern the most convenient path to follow. Our laws are therefore like those of an absolute monarch, who is wise and consults his council of state.

Which of the following would be the most appropriate conclusion?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

How much faith a person requires in order to flourish, how much "fixed opinion" he requires which he does not wish to have shaken, because he holds himself thereby is a measure of his power (or more plainly speaking, of his weakness). Most people in old Europe, as it seems to me, still need Christianity at present, and on that account it still finds belief.

For such is man: a theological dogma might be refuted to him a thousand times, provided, however, that he had need of it, he would again and again accept it as "true," according to the famous "proof of power" of which the Bible speaks. Some have still need of metaphysics; but also the impatient longing for certainty which at present discharges itself in scientific, positivist fashion among large numbers of the people, the longing by all means to get at something stable (while on account of the warmth of the longing the establishing of the certainty is more leisurely and negligently undertaken): even this is still the longing for a hold, a support; in short, the instinct of weakness, which, while not actually creating religions, nevertheless preserves them.

In fact, around all these positivist systems there fume the vapours of a certain pessimistic gloom, something of weariness, fatalism, disillusionment, and tear of new disillusionment or else manifest animosity, ill-humour, anarchic exasperation, and whatever there is of symptom or masquerade of the feeling of weakness.

Belief is always most desired, most pressingly needed, where there is a lack of will: for the will, as emotion of command, is the distinguishing characteristic of sovereignty and power. That is to say, the less a person knows how to command, the more urgent is his desire for that which commands, and commands sternly, a God, a prince, a caste, a physician, a confessor, a dogma, a party conscience.

Fanaticism is the sole "volitional strength" to which the weak and irresolute can be excited, as a sort of hypnotising of the entire sensory-intellectual system, in favour of the over-abundant nutrition (hypertrophy) of a particular point of view and a particular sentiment, which then dominates the Christian calls it his faith. When a man arrives at the fundamental conviction that he requires to be commanded, he becomes "a believer." Reversely, one could imagine a delight and a power of self-determining, and a freedom of will, whereby a spirit could bid farewell to every belief, to every wish for certainty, accustomed as it would be to support itself on slender cords and possibilities, and to dance even on the verge of abysses. Such a spirit would be the spirit par excellence.

Which of the following does the author believe to be the reason why Christianity still survives in the modern world?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

How much faith a person requires in order to flourish, how much "fixed opinion" he requires which he does not wish to have shaken, because he holds himself thereby is a measure of his power (or more plainly speaking, of his weakness). Most people in old Europe, as it seems to me, still need Christianity at present, and on that account it still finds belief.

For such is man: a theological dogma might be refuted to him a thousand times, provided, how ever, that he had need of it, he would again and again accept it as "true," according to the famous "proof of power" of which the Bible speaks. Some have still need of metaphysics; but also the impatient longing for certainty which at present discharges itself in scientific, positivist fashion among large numbers of the people, the longing by all means to get at something stable (while on account of the warmth of the longing the establishing of the certainty is more leisurely and negligently undertaken): even this is still the longing for a hold, a support; in short, the instinct of weakness, which, while not actually creating religions, nevertheless preserves them.

In fact, around all these positivist systems there fume the vapours of a certain pessimistic gloom, something of weariness, fatalism, disillusionment, and tear of new disillusionment or else manifest animosity, ill-humour, anarchic exasperation, and whatever there is of symptom or masquerade of the feeling of weakness.

Belief is always most desired, most pressingly needed, where there is a lack of will: for the will, as emotion of command, is the distinguishing characteristic of sovereignty and power. That is to say, the less a person knows how to command, the more urgent is his desire for that which commands, and commands sternly, a God, a prince, a caste, a physician, a confessor, a dogma, a party conscience.

Fanaticism is the sole "volitional strength" to which the weak and irresolute can be excited, as a sort of hypnotising of the entire sensory-intellectual system, in favour of the over-abundant nutrition (hypertrophy) of a particular point of view and a particular sentiment, which then dominates the Christian calls it his faith. When a man arrives at the fundamental conviction that he requires to be commanded, he becomes "a believer." Reversely, one could imagine a delight and a power of self-determining, and a freedom of will, whereby a spirit could bid farewell to every belief, to every wish for certainty, accustomed as it would be to support itself on slender cords and possibilities, and to dance even on the verge of abysses. Such a spirit would be the spirit par excellence.

The tone of the passage can best be characterized as:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

How much faith a person requires in order to flourish, how much "fixed opinion" he requires which he does not wish to have shaken, because he holds himself thereby is a measure of his power (or more plainly speaking, of his weakness). Most people in old Europe, as it seems to me, still need Christianity at present, and on that account it still finds belief.

For such is man: a theological dogma might be refuted to him a thousand times, provided, how ever, that he had need of it, he would again and again accept it as "true," according to the famous "proof of power" of which the Bible speaks. Some have still need of metaphysics; but also the impatient longing for certainty which at present discharges itself in scientific, positivist fashion among large numbers of the people, the longing by all means to get at something stable (while on account of the warmth of the longing the establishing of the certainty is more leisurely and negligently undertaken): even this is still the longing for a hold, a support; in short, the instinct of weakness, which, while not actually creating religions, nevertheless preserves them.

In fact, around all these positivist systems there fume the vapours of a certain pessimistic gloom, something of weariness, fatalism, disillusionment, and tear of new disillusionment or else manifest animosity, ill-humour, anarchic exasperation, and whatever there is of symptom or masquerade of the feeling of weakness.

Belief is always most desired, most pressingly needed, where there is a lack of will: for the will, as emotion of command, is the distinguishing characteristic of sovereignty and power. That is to say, the less a person knows how to command, the more urgent is his desire for that which commands, and commands sternly, a God, a prince, a caste, a physician, a confessor, a dogma, a party conscience.

Fanaticism is the sole "volitional strength" to which the weak and irresolute can be excited, as a sort of hypnotising of the entire sensory-intellectual system, in favour of the over-abundant nutrition (hypertrophy) of a particular point of view and a particular sentiment, which then dominates the Christian calls it his faith. When a man arrives at the fundamental conviction that he requires to be commanded, he becomes "a believer." Reversely, one could imagine a delight and a power of self-determining, and a freedom of will, whereby a spirit could bid farewell to every belief, to every wish for certainty, accustomed as it would be to support itself on slender cords and possibilities, and to dance even on the verge of abysses. Such a spirit would be the spirit par excellence.

What does the author refer to when he talks about 'positivist systems' in the third paragraph?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When the anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the declining strata of society, demands with a fine indignation what is "right," "justice," and "equal rights," he is merely under the pressure of his own uncultured state, which cannot comprehend the real reason for his suffering - what it is that he is poor in: life. A causal instinct asserts itself in him: it must be somebody's fault that he is in a bad way.

Also, the "fine indignation" itself soothes him; it is a pleasure for all wretched devils to scold: it gives a slight but intoxicating sense of power. Even plaintiveness and complaining can give life a charm for the sake of which one endures it: there is a fine dose of revenge in every complaint; one charges one's own bad situation, and under certain circumstances even one's own badness, to those who are different, as if that were an injustice, a forbidden privilege. "If I am canaille, you ought to be too" - on such logic are revolutions made.

Complaining is never any good: it stems from weakness. Whether one charges one's misfortune to others or to oneself - the socialist does the former; the Christian, for example, the latter - really makes no difference. The common and, let us add, the unworthy thing is that it is supposed to be somebody's fault that one is suffering; in short, that the sufferer prescribes the honey of revenge for himself against his suffering. The objects of this need for revenge, as a need for pleasure, are mere occasions: everywhere the sufferer finds occasions for satisfying his little revenge. If he is a Christian - to repeat it once more - he finds them in himself.

The Christian and the anarchist are both decadents. When the Christian condemns, slanders, and besmirches "the world," his instinct is the same as that which prompts the socialist worker to condemn, slander, and besmirch society. The "last judgment" is the sweet comfort of revenge - the revolution, which the socialist worker also awaits, but conceived as a little farther off. The "beyond" - why a beyond, if not as a means for besmirching this world?

It can be inferred from the passage that:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When the anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the declining strata of society, demands with a fine indignation what is "right," "justice," and "equal rights," he is merely under the pressure of his own uncultured state, which cannot comprehend the real reason for his suffering - what it is that he is poor in: life. A causal instinct asserts itself in him: it must be somebody's fault that he is in a bad way.

Also, the "fine indignation" itself soothes him; it is a pleasure for all wretched devils to scold: it gives a slight but intoxicating sense of power. Even plaintiveness and complaining can give life a charm for the sake of which one endures it: there is a fine dose of revenge in every complaint; one charges one's own bad situation, and under certain circumstances even one's own badness, to those who are different, as if that were an injustice, a forbidden privilege. "If I am canaille, you ought to be too" - on such logic are revolutions made.

Complaining is never any good: it stems from weakness. Whether one charges one's misfortune to others or to oneself - the socialist does the former; the Christian, for example, the latter - really makes no difference. The common and, let us add, the unworthy thing is that it is supposed to be somebody's fault that one is suffering; in short, that the sufferer prescribes the honey of revenge for himself against his suffering. The objects of this need for revenge, as a need for pleasure, are mere occasions: everywhere the sufferer finds occasions for satisfying his little revenge. If he is a Christian - to repeat it once more - he finds them in himself.

The Christian and the anarchist are both decadents. When the Christian condemns, slanders, and besmirches "the world," his instinct is the same as that which prompts the socialist worker to condemn, slander, and besmirch society. The "last judgment" is the sweet comfort of revenge - the revolution, which the socialist worker also awaits, but conceived as a little farther off. The "beyond" - why a beyond, if not as a means for besmirching this world?

The tone of the passage can best be characterized as:

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When the anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the declining strata of society, demands with a fine indignation what is "right," "justice," and "equal rights," he is merely under the pressure of his own uncultured state, which cannot comprehend the real reason for his suffering - what it is that he is poor in: life. A causal instinct asserts itself in him: it must be somebody's fault that he is in a bad way.

Also, the "fine indignation" itself soothes him; it is a pleasure for all wretched devils to scold: it gives a slight but intoxicating sense of power. Even plaintiveness and complaining can give life a charm for the sake of which one endures it: there is a fine dose of revenge in every complaint; one charges one's own bad situation, and under certain circumstances even one's own badness, to those who are different, as if that were an injustice, a forbidden privilege. "If I am canaille, you ought to be too" - on such logic are revolutions made.

Complaining is never any good: it stems from weakness. Whether one charges one's misfortune to others or to oneself - the socialist does the former; the Christian, for example, the latter - really makes no difference. The common and, let us add, the unworthy thing is that it is supposed to be somebody's fault that one is suffering; in short, that the sufferer prescribes the honey of revenge for himself against his suffering. The objects of this need for revenge, as a need for pleasure, are mere occasions: everywhere the sufferer finds occasions for satisfying his little revenge. If he is a Christian - to repeat it once more - he finds them in himself.

The Christian and the anarchist are both decadents. When the Christian condemns, slanders, and besmirches "the world," his instinct is the same as that which prompts the socialist worker to condemn, slander, and besmirch society. The "last judgment" is the sweet comfort of revenge - the revolution, which the socialist worker also awaits, but conceived as a little farther off. The "beyond" - why a beyond, if not as a means for besmirching this world?

The second paragraph begins with: 'Also, the "fine indignation" itself soothes him..' To whom is the author referring?

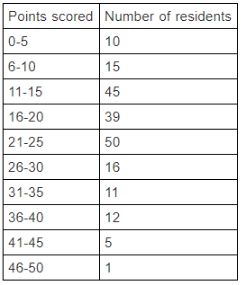

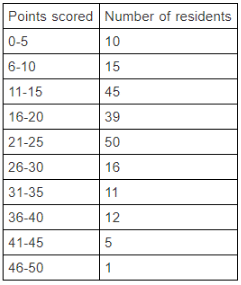

Directions : Aashapurna housing society' has apartments in two wings: east wing and west wing. On occasion of Christmas there is a get-together event being organized by the working committee (WC) of the society. An event comprising a quiz competition, a dumb charades game and a spin the bottle game is to take place, but since all residents of society cannot participate, a pre-final event within the east and west wings takes place separately and selected participant out of these events would compete in final against each other. Secretary of east wing of society supervises the games within his wing and allows each resident to take part in only one game of their choice. All participants of quiz contest are asked 50 questions each and get 1 point for 1 correct answer and 0 point for a wrong answer. All participants of dumb charade are given 50 chances to guess names of 50 movies, and get 1 point for 1 correct guess provided they do not guess a wrong movie name, after which they are considered out of game. Each participant of spin the bottle play 50 rounds of game together and winner of each round gets 1 point and others get 0 point. So, if there are 'n' number of participants then we get '50n' rounds. The game is based on sheer chance. After all games are conducted, the points distribution for East wing residents for quiz competition turned out to be as given below. The similar score was observed for the other two games as well.

Answer following questions based on the above information, considering that the following questions are for the final rounds that are to be conducted:

Three teams comprising of two participants each is to be selected for quiz competition, what should be the criteria for selection of the teams?

Directions: Aashapurna housing society' has apartments in two wings: east wing and west wing. On occasion of Christmas there is a get-together event being organized by the working committee (WC) of the society. An event comprising a quiz competition, a dumb charades game and a spin the bottle game is to take place, but since all residents of society cannot participate, a pre-final event within the east and west wings takes place separately and selected participant out of these events would compete in final against each other. Secretary of east wing of society supervises the games within his wing and allows each resident to take part in only one game of their choice. All participants of quiz contest are asked 50 questions each and get 1 point for 1 correct answer and 0 point for a wrong answer. All participants of dumb charade are given 50 chances to guess names of 50 movies, and get 1 point for 1 correct guess provided they do not guess a wrong movie name, after which they are considered out of game. Each participant of spin the bottle play 50 rounds of game together and winner of each round gets 1 point and others get 0 point. So, if there are 'n' number of participants then we get '50n' rounds. The game is based on sheer chance. After all games are conducted, the points distribution for East wing residents for quiz competition turned out to be as given below. The similar score was observed for the other two games as well.

Answer following questions based on the above information, considering that the following questions are for the final rounds that are to be conducted:

Which of the following would be the best way for selecting a dumb charade team of 5 members?

Directions: Read the poem carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave

In the world's broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe'er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act, - act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o'erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o'er life's solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labour and to wait.

What is the overall tone of the poem?

Directions: Read the following passage carefully and answer the questions given below it.

When the anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the declining strata of society, demands with a fine indignation what is "right," "justice," and "equal rights," he is merely under the pressure of his own uncultured state, which cannot comprehend the real reason for his suffering - what it is that he is poor in: life. A causal instinct asserts itself in him: it must be somebody's fault that he is in a bad way.

Also, the "fine indignation" itself soothes him; it is a pleasure for all wretched devils to scold: it gives a slight but intoxicating sense of power. Even plaintiveness and complaining can give life a charm for the sake of which one endures it: there is a fine dose of revenge in every complaint; one charges one's own bad situation, and under certain circumstances even one's own badness, to those who are different, as if that were an injustice, a forbidden privilege. "If I am canaille, you ought to be too" - on such logic are revolutions made.

Complaining is never any good: it stems from weakness. Whether one charges one's misfortune to others or to oneself - the socialist does the former; the Christian, for example, the latter - really makes no difference. The common and, let us add, the unworthy thing is that it is supposed to be somebody's fault that one is suffering; in short, that the sufferer prescribes the honey of revenge for himself against his suffering. The objects of this need for revenge, as a need for pleasure, are mere occasions: everywhere the sufferer finds occasions for satisfying his little revenge. If he is a Christian - to repeat it once more - he finds them in himself.

The Christian and the anarchist are both decadents. When the Christian condemns, slanders, and besmirches "the world," his instinct is the same as that which prompts the socialist worker to condemn, slander, and besmirch society. The "last judgment" is the sweet comfort of revenge - the revolution, which the socialist worker also awaits, but conceived as a little farther off. The "beyond" - why a beyond, if not as a means for besmirching this world?

What is the closest interpretation of "Be not like dumb, driven cattle! Be a hero in the strife!"?

What is the significance of the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in Indian cinema?

What is the primary purpose of the Harpoon anti-ship missile system?

What is the minimum annual income required for an applicant to be eligible for Taiwan's Global Elite Card?

What is the primary purpose of the National Agriculture Code (NAC) being developed by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS)?

What role does Section 40 play in the functioning of the Waqf Board according to the Waqf Act?

Which countries, alongside India, have shown improvements in the UNCTAD ranking due to enhanced human capital?

Consider the following pairs regarding the Deputy Speaker of Lok Sabha:

1. Article 93 - Mandates election of Speaker and Deputy Speaker by the President.

2. Article 95(1) - Deputy Speaker performs the Speaker's duties in their absence.

3. Election Process - The Deputy Speaker is elected by a simple majority of members present and voting.

4. Tenure - Deputy Speaker's tenure is fixed for a term of five years.

How many pairs given above are correctly matched?

Consider the following statements :

Statement-I:

The Deputy Speaker of Lok Sabha is elected by a simple majority of Lok Sabha members present and voting.

Statement-II:

The Deputy Speaker serves during the Lok Sabha's life but can be removed by a majority vote under specific conditions.

Which one of the following is correct in respect of the above statements ?

What has been highlighted as a significant advantage of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in India by 2030?

Consider the following statements:

1. Between 2011-12 and 2022-23, India reduced rural poverty from 18.4% to 2.8%.

2. By 2022-23, the five most populous states in India accounted for only half of the decline in extreme poverty.

3. India's Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) showed an improvement from 53.8% in 2005-06 to 16.4% in 2019-21.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

Consider the following statements regarding Google's Ironwood TPU and India's ethanol production strategy:

1. Ironwood TPU is designed specifically for executing AI models like Large Language Models (LLMs) and Mixture of Experts (MoEs).

2. India's ethanol blending program aims to achieve a 20% ethanol blend in petrol by the year 2025-26.

3. The Ironwood TPU uses more energy per watt than its predecessor due to its advanced liquid cooling technology.