CAT Mock Test- 3 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test- 3

According to the author, Deja vu is almost impossible to study because:

Which of the following statements CANNOT be inferred from the passage?

Which of the following is NOT one of the theories attempting to explain deja-vu?

In the first paragraph, what is the "conflict" that the author refers to?

Authoritarian political systems echo monotheistic religions in that:

All of the following have not been discussed in the passage except:

Which of the following cannot be said to be true based on the passage?

I. Submission of personal objectives for a greater collective cause is an essential feature of authoritarian regimes.

II. According to the author, oppositions of the authoritarian leader are allies of evil.

III. Followers of monotheistic religions are highly supportive of authoritarian political systems.

Which of the following best describes the reason why the author terms the concept 'performative authenticity' paradoxical?

According to Charles Guignon, finding one's true self involves all of the following, EXCEPT:

Which of the following statements is the author LEAST likely to agree with?

The inner and performative modes of authenticity differ in all of the following ways, EXCEPT:

Which of the following statements is definitely TRUE according to the passage?

According to the passage, academic and amateur fossil hunters paid little attention to tropical forests because:

Which of the following statements CAN be inferred from the passage?

I. The tropical rain forest ecosystem would not have developed had the dinosaurs not gone extinct.

II. Location of the impact crater is crucial to understanding the effects of the meteoritic collision.

III. The effects of the collision on African tropical rain forests were not known until recently.

IV. Fires caused by the meteoritic collision led to the depletion of soil nutrients.

According to the passage, all of the following aided in the emergence of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, EXCEPT:

DIRECTIONS for the question: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- Competition is the driving force behind the real benefits such systems achieve, but the logic of competition also imprisons its players to stay within their roles.

- Liberal democracy is like capitalism, a game designed to make its players compete against each other for points and prizes.

- As a result, democracies are surprisingly vulnerable to take over, as we have seen from the recent examples of Turkey, Hungary, and India.

- It is no one's job to defend the system of rules governing that competition.

DIRECTIONS for the question: The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- By definition, parasites live in or on a host and take something from that host.

- Scientists warn of dire consequences if we disregard the rest.

- This has made them the pariahs of the animal world.

- But not all parasites cause noticeable harm to their hosts, and only a small percentage affect humans.

The passage given below is followed by four summaries. Choose the option that best captures the author’s position.

The magnitude of plastic packaging that is used and casually discarded — air pillows, Bubble Wrap, shrink wrap, envelopes, bags — portends gloomy consequences. These single-use items are primarily made from polyethylene, though vinyl is also used. In marine environments, this plastic waste can cause disease and death for coral, fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Plastic debris is often mistaken for food, and microplastics release chemical toxins as they degrade. Data suggests that plastics have infiltrated human food webs and placentas. These plastics have the potential to disrupt the endocrine system, which releases hormones into the bloodstream that help control growth and development during childhood, among many other important processes.

Five jumbled-up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer.

1. Over the past fortnight, one of its finest and most celebrated champions managed to match Winbeldon's grandeur again.

2. Wimbledon’s grandeur and enigma evoke a sense of timelessness and mystique.

3. At 35 years and 342 days, Roger Federer was crowned the Wimbledon champion for the 8th time thereby becoming the oldest man to win the Wimbledon singles title in the open era.

4. Once he had won the first three rounds, the semi-finals and finals witnessed the true magic of a rested Federer

5. Given that his game isn’t reliant on explosive athleticism or muscular power ball striking, both of which are vulnerable to decay with age, there is a high chance that the reign of King Federer will continue further into the future

Five jumbled-up sentences, related to a topic, are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a coherent paragraph. Identify the odd one out and key in the number of the sentence as your answer.

1. Quantum computing harnesses the peculiar dynamics of quantum physics to process information in novel ways.

2. Classical computing, the traditional form, operates with binary bits using 0s and 1s in a linear sequence.

3. The advent of quantum algorithms promises resolutions to complex problems unreachable by current machines.

4. These systems are revolutionizing climate study simulations with their advanced modeling.

5. In stark contrast, quantum bits, or qubits, can hold a vast amount of information, expanding computational boundaries exponentially.

Direction: Choose the most logical order of sentences from among the given choices to construct a coherent paragraph.

1. This is only partially true because while most of the fighting did take place on the continent, one of the largest and most sophisticated undertakings of the war was conducted mainly at sea.

2. While the land war certainly contributed to the Entente's (Britain, France, Italy, U.S.) victory in 1918, it was the blockade that truly broke Germany's back.

3. This operation was the British blockade from 1914-1919 which sought to obstruct Germany's ability to import goods, and thus in the most literal sense starve the German people and military into submission.

4. The First World War is largely thought of as a conflict where the majority of the significant operations took place almost exclusively on mainland Europe with the exception of a handful of naval clashes fought throughout the world's oceans.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

The debate over artificial intelligence's threats and promises is multifaceted. Critics argue that AI could eventually surpass human intelligence, making decisions incompatible with human survival. However, proponents believe AI, guided by regulations, has the potential to eradicate poverty and disease. The crux of the matter lies not in AI's capabilities but in human management.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Globalization promised an interconnected world, but it also led to significant parts of entire populations feeling left behind, stirring discontent and sociopolitical backlash. This unintended consequence has seen the rise of protectionism and nationalism, as those adversely affected seek to reclaim control over their economic prospects.

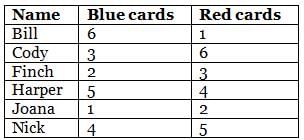

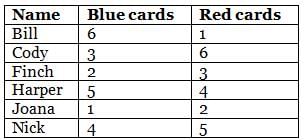

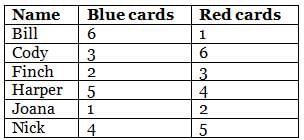

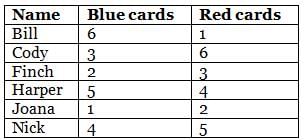

How many people have less cards than Harper in both blue and red colours?

Who has the same number of blue cards as the number of red cards with Bill?