CAT Mock Test- 8 - CAT MCQ

30 Questions MCQ Test - CAT Mock Test- 8

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The word “bias” commonly appears in conversations about mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions. We use it when there is discrimination, for instance against women or in favor of Ivy League graduates. But the meaning of the word is broader: A bias is any predictable error that inclines your judgment in a particular direction. For instance, we speak of bias when forecasts of sales are consistently optimistic or investment decisions overly cautious.

Society has devoted a lot of attention to the problem of bias — and rightly so. But when it comes to mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions, there is another type of error that attracts far less attention: noise. To see the difference between bias and noise, consider your bathroom scale. If on average the readings it gives are too high (or too low), the scale is biased. If it shows different readings when you step on it several times in quick succession, the scale is noisy. While bias is the average of errors, noise is their variability.

Although it is often ignored, noise is a large source of malfunction in society. In a 1981 study, for example, 208 federal judges were asked to determine the appropriate sentences for the same 16 cases. The cases were described by the characteristics of the offense (robbery or fraud, violent or not) and of the defendant (young or old, repeat or first-time offender, accomplice or principal). The average difference between the sentences that two randomly chosen judges gave for the same crime was more than 3.5 years. Considering that the mean sentence was seven years, that was a disconcerting amount of noise. Noise in real courtrooms is surely only worse, as actual cases are more complex and difficult to judge than stylized vignettes. It is hard to escape the conclusion that sentencing is in part a lottery, because the punishment can vary by many years depending on which judge is assigned to the case and on the judge’s state of mind on that day. The judicial system is unacceptably noisy.

Noise causes error, as does bias, but the two kinds of error are separate and independent. A company’s hiring decisions could be unbiased overall if some of its recruiters favor men and others favor women. However, its hiring decisions would be noisy, and the company would make many bad choices. Where does noise come from? There is much evidence that irrelevant circumstances can affect judgments. In the case of criminal sentencing, for instance, a judge’s mood, fatigue and even the weather can all have modest but detectable effects on judicial decisions. Another source of noise is that people can have different general tendencies. Judges often vary in the severity of the sentences they mete out: There are “hanging” judges and lenient ones.

A third source of noise is less intuitive, although it is usually the largest: People can have not only different general tendencies (say, whether they are harsh or lenient) but also different patterns of assessment (say, which types of cases they believe merit being harsh or lenient about). Underwriters differ in their views of what is risky, and doctors in their views of which ailments require treatment. We celebrate the uniqueness of individuals, but we tend to forget that, when we expect consistency, uniqueness becomes a liability.

Q. Which of the following statements is the author most likely to agree with?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The word “bias” commonly appears in conversations about mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions. We use it when there is discrimination, for instance against women or in favor of Ivy League graduates. But the meaning of the word is broader: A bias is any predictable error that inclines your judgment in a particular direction. For instance, we speak of bias when forecasts of sales are consistently optimistic or investment decisions overly cautious.

Society has devoted a lot of attention to the problem of bias — and rightly so. But when it comes to mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions, there is another type of error that attracts far less attention: noise. To see the difference between bias and noise, consider your bathroom scale. If on average the readings it gives are too high (or too low), the scale is biased. If it shows different readings when you step on it several times in quick succession, the scale is noisy. While bias is the average of errors, noise is their variability.

Although it is often ignored, noise is a large source of malfunction in society. In a 1981 study, for example, 208 federal judges were asked to determine the appropriate sentences for the same 16 cases. The cases were described by the characteristics of the offense (robbery or fraud, violent or not) and of the defendant (young or old, repeat or first-time offender, accomplice or principal). The average difference between the sentences that two randomly chosen judges gave for the same crime was more than 3.5 years. Considering that the mean sentence was seven years, that was a disconcerting amount of noise. Noise in real courtrooms is surely only worse, as actual cases are more complex and difficult to judge than stylized vignettes. It is hard to escape the conclusion that sentencing is in part a lottery, because the punishment can vary by many years depending on which judge is assigned to the case and on the judge’s state of mind on that day. The judicial system is unacceptably noisy.

Noise causes error, as does bias, but the two kinds of error are separate and independent. A company’s hiring decisions could be unbiased overall if some of its recruiters favor men and others favor women. However, its hiring decisions would be noisy, and the company would make many bad choices. Where does noise come from? There is much evidence that irrelevant circumstances can affect judgments. In the case of criminal sentencing, for instance, a judge’s mood, fatigue and even the weather can all have modest but detectable effects on judicial decisions. Another source of noise is that people can have different general tendencies. Judges often vary in the severity of the sentences they mete out: There are “hanging” judges and lenient ones.

A third source of noise is less intuitive, although it is usually the largest: People can have not only different general tendencies (say, whether they are harsh or lenient) but also different patterns of assessment (say, which types of cases they believe merit being harsh or lenient about). Underwriters differ in their views of what is risky, and doctors in their views of which ailments require treatment. We celebrate the uniqueness of individuals, but we tend to forget that, when we expect consistency, uniqueness becomes a liability.

Q. Which of the following can serve as an example of 'noise' as per the the passage?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The word “bias” commonly appears in conversations about mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions. We use it when there is discrimination, for instance against women or in favor of Ivy League graduates. But the meaning of the word is broader: A bias is any predictable error that inclines your judgment in a particular direction. For instance, we speak of bias when forecasts of sales are consistently optimistic or investment decisions overly cautious.

Society has devoted a lot of attention to the problem of bias — and rightly so. But when it comes to mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions, there is another type of error that attracts far less attention: noise. To see the difference between bias and noise, consider your bathroom scale. If on average the readings it gives are too high (or too low), the scale is biased. If it shows different readings when you step on it several times in quick succession, the scale is noisy. While bias is the average of errors, noise is their variability.

Although it is often ignored, noise is a large source of malfunction in society. In a 1981 study, for example, 208 federal judges were asked to determine the appropriate sentences for the same 16 cases. The cases were described by the characteristics of the offense (robbery or fraud, violent or not) and of the defendant (young or old, repeat or first-time offender, accomplice or principal). The average difference between the sentences that two randomly chosen judges gave for the same crime was more than 3.5 years. Considering that the mean sentence was seven years, that was a disconcerting amount of noise. Noise in real courtrooms is surely only worse, as actual cases are more complex and difficult to judge than stylized vignettes. It is hard to escape the conclusion that sentencing is in part a lottery, because the punishment can vary by many years depending on which judge is assigned to the case and on the judge’s state of mind on that day. The judicial system is unacceptably noisy.

Noise causes error, as does bias, but the two kinds of error are separate and independent. A company’s hiring decisions could be unbiased overall if some of its recruiters favor men and others favor women. However, its hiring decisions would be noisy, and the company would make many bad choices. Where does noise come from? There is much evidence that irrelevant circumstances can affect judgments. In the case of criminal sentencing, for instance, a judge’s mood, fatigue and even the weather can all have modest but detectable effects on judicial decisions. Another source of noise is that people can have different general tendencies. Judges often vary in the severity of the sentences they mete out: There are “hanging” judges and lenient ones.

A third source of noise is less intuitive, although it is usually the largest: People can have not only different general tendencies (say, whether they are harsh or lenient) but also different patterns of assessment (say, which types of cases they believe merit being harsh or lenient about). Underwriters differ in their views of what is risky, and doctors in their views of which ailments require treatment. We celebrate the uniqueness of individuals, but we tend to forget that, when we expect consistency, uniqueness becomes a liability.

Q. According to the passage, noise in a judicial system could lead to which of the following consequences?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

The word “bias” commonly appears in conversations about mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions. We use it when there is discrimination, for instance against women or in favor of Ivy League graduates. But the meaning of the word is broader: A bias is any predictable error that inclines your judgment in a particular direction. For instance, we speak of bias when forecasts of sales are consistently optimistic or investment decisions overly cautious.

Society has devoted a lot of attention to the problem of bias — and rightly so. But when it comes to mistaken judgments and unfortunate decisions, there is another type of error that attracts far less attention: noise. To see the difference between bias and noise, consider your bathroom scale. If on average the readings it gives are too high (or too low), the scale is biased. If it shows different readings when you step on it several times in quick succession, the scale is noisy. While bias is the average of errors, noise is their variability.

Although it is often ignored, noise is a large source of malfunction in society. In a 1981 study, for example, 208 federal judges were asked to determine the appropriate sentences for the same 16 cases. The cases were described by the characteristics of the offense (robbery or fraud, violent or not) and of the defendant (young or old, repeat or first-time offender, accomplice or principal). The average difference between the sentences that two randomly chosen judges gave for the same crime was more than 3.5 years. Considering that the mean sentence was seven years, that was a disconcerting amount of noise. Noise in real courtrooms is surely only worse, as actual cases are more complex and difficult to judge than stylized vignettes. It is hard to escape the conclusion that sentencing is in part a lottery, because the punishment can vary by many years depending on which judge is assigned to the case and on the judge’s state of mind on that day. The judicial system is unacceptably noisy.

Noise causes error, as does bias, but the two kinds of error are separate and independent. A company’s hiring decisions could be unbiased overall if some of its recruiters favor men and others favor women. However, its hiring decisions would be noisy, and the company would make many bad choices. Where does noise come from? There is much evidence that irrelevant circumstances can affect judgments. In the case of criminal sentencing, for instance, a judge’s mood, fatigue and even the weather can all have modest but detectable effects on judicial decisions. Another source of noise is that people can have different general tendencies. Judges often vary in the severity of the sentences they mete out: There are “hanging” judges and lenient ones.

A third source of noise is less intuitive, although it is usually the largest: People can have not only different general tendencies (say, whether they are harsh or lenient) but also different patterns of assessment (say, which types of cases they believe merit being harsh or lenient about). Underwriters differ in their views of what is risky, and doctors in their views of which ailments require treatment. We celebrate the uniqueness of individuals, but we tend to forget that, when we expect consistency, uniqueness becomes a liability.

Q. According to the passage, noise and bias differ in which of the following ways?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Information has never been more accessible or less reliable. So we are advised to check our sources carefully. There is so much talk of “fake news” that the term has entirely lost meaning. At school, we are taught to avoid Wikipedia, or at the very least never admit to using it in our citations. And most sources on the world wide web have been built without the standardized attributions that scaffold other forms of knowledge dissemination; they are therefore seen as degraded, even as they illuminate.

But it was only relatively recently that academic disciplines designed rigid systems for categorizing and organizing source material at all. Historian Anthony Grafton traces the genealogy of the footnote in an excellent book, which reveals many origin stories. It turns out that footnotes are related to early systems of marginalia, glosses, and annotation that existed in theology, early histories, and Medieval law. The footnote in something like its modern form seems to have been devised in the seventeenth century, and has proliferated since, with increasing standardization and rigor. And yet, Grafton writes, “appearances of uniformity are deceptive. To the inexpert, footnotes look like deep root systems, solid and fixed; to the connoisseur, however, they reveal themselves as anthills, swarming with constructive and combative activity.”

The purpose of citation, broadly speaking, is to give others credit, but it does much more than that. Famously, citations can be the sources of great enmity — a quick dismissal of a rival argument with a “cf.” They can serve a social purpose, as sly thank-yous to friends and mentors. They can perform a kind of box-checking of requisite major works. (As Grafton points out, the omission of these works can itself be a statement.) Attribution, significantly, allows others to check your work, or at least gives the illusion that they could, following a web of sources back to the origins. But perhaps above all else, citations serve a dual purpose that seems at once complementary and conflicting; they acknowledge a debt to a larger body of work while also conferring on oneself a certain kind of erudition and expertise.

Like many systems that appear meticulous, the writing of citations is a subjective art. Never more so than in fiction, where citation is an entirely other kind of animal, not required or even expected, except in the “acknowledgments” page, which is often a who’s who of the publishing world. But in the last two decades, bibliographies and sources cited pages have increasingly cropped up in the backs of novels. “It’s terribly off-putting,” James Wood said of this fad in 2006. “It would be very odd if Thomas Hardy had put at the end of all his books, ‘I’m thankful to the Dorset County Chronicle for dialect books from the 18th century.’ We expect authors to do that work, and I don’t see why we should praise them for that work.” Wood has a point, or had one — at their worst, citations in fiction are annoying, driven by an author’s anxiety to show off what he has read, to check the right boxes.

Q. Which of the following is a reason why citation is done?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Information has never been more accessible or less reliable. So we are advised to check our sources carefully. There is so much talk of “fake news” that the term has entirely lost meaning. At school, we are taught to avoid Wikipedia, or at the very least never admit to using it in our citations. And most sources on the world wide web have been built without the standardized attributions that scaffold other forms of knowledge dissemination; they are therefore seen as degraded, even as they illuminate.

But it was only relatively recently that academic disciplines designed rigid systems for categorizing and organizing source material at all. Historian Anthony Grafton traces the genealogy of the footnote in an excellent book, which reveals many origin stories. It turns out that footnotes are related to early systems of marginalia, glosses, and annotation that existed in theology, early histories, and Medieval law. The footnote in something like its modern form seems to have been devised in the seventeenth century, and has proliferated since, with increasing standardization and rigor. And yet, Grafton writes, “appearances of uniformity are deceptive. To the inexpert, footnotes look like deep root systems, solid and fixed; to the connoisseur, however, they reveal themselves as anthills, swarming with constructive and combative activity.”

The purpose of citation, broadly speaking, is to give others credit, but it does much more than that. Famously, citations can be the sources of great enmity — a quick dismissal of a rival argument with a “cf.” They can serve a social purpose, as sly thank-yous to friends and mentors. They can perform a kind of box-checking of requisite major works. (As Grafton points out, the omission of these works can itself be a statement.) Attribution, significantly, allows others to check your work, or at least gives the illusion that they could, following a web of sources back to the origins. But perhaps above all else, citations serve a dual purpose that seems at once complementary and conflicting; they acknowledge a debt to a larger body of work while also conferring on oneself a certain kind of erudition and expertise.

Like many systems that appear meticulous, the writing of citations is a subjective art. Never more so than in fiction, where citation is an entirely other kind of animal, not required or even expected, except in the “acknowledgments” page, which is often a who’s who of the publishing world. But in the last two decades, bibliographies and sources cited pages have increasingly cropped up in the backs of novels. “It’s terribly off-putting,” James Wood said of this fad in 2006. “It would be very odd if Thomas Hardy had put at the end of all his books, ‘I’m thankful to the Dorset County Chronicle for dialect books from the 18th century.’ We expect authors to do that work, and I don’t see why we should praise them for that work.” Wood has a point, or had one — at their worst, citations in fiction are annoying, driven by an author’s anxiety to show off what he has read, to check the right boxes.

Q. What can be inferred about the author's stance on including citations in works of fiction from the passage?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Information has never been more accessible or less reliable. So we are advised to check our sources carefully. There is so much talk of “fake news” that the term has entirely lost meaning. At school, we are taught to avoid Wikipedia, or at the very least never admit to using it in our citations. And most sources on the world wide web have been built without the standardized attributions that scaffold other forms of knowledge dissemination; they are therefore seen as degraded, even as they illuminate.

But it was only relatively recently that academic disciplines designed rigid systems for categorizing and organizing source material at all. Historian Anthony Grafton traces the genealogy of the footnote in an excellent book, which reveals many origin stories. It turns out that footnotes are related to early systems of marginalia, glosses, and annotation that existed in theology, early histories, and Medieval law. The footnote in something like its modern form seems to have been devised in the seventeenth century, and has proliferated since, with increasing standardization and rigor. And yet, Grafton writes, “appearances of uniformity are deceptive. To the inexpert, footnotes look like deep root systems, solid and fixed; to the connoisseur, however, they reveal themselves as anthills, swarming with constructive and combative activity.”

The purpose of citation, broadly speaking, is to give others credit, but it does much more than that. Famously, citations can be the sources of great enmity — a quick dismissal of a rival argument with a “cf.” They can serve a social purpose, as sly thank-yous to friends and mentors. They can perform a kind of box-checking of requisite major works. (As Grafton points out, the omission of these works can itself be a statement.) Attribution, significantly, allows others to check your work, or at least gives the illusion that they could, following a web of sources back to the origins. But perhaps above all else, citations serve a dual purpose that seems at once complementary and conflicting; they acknowledge a debt to a larger body of work while also conferring on oneself a certain kind of erudition and expertise.

Like many systems that appear meticulous, the writing of citations is a subjective art. Never more so than in fiction, where citation is an entirely other kind of animal, not required or even expected, except in the “acknowledgments” page, which is often a who’s who of the publishing world. But in the last two decades, bibliographies and sources cited pages have increasingly cropped up in the backs of novels. “It’s terribly off-putting,” James Wood said of this fad in 2006. “It would be very odd if Thomas Hardy had put at the end of all his books, ‘I’m thankful to the Dorset County Chronicle for dialect books from the 18th century.’ We expect authors to do that work, and I don’t see why we should praise them for that work.” Wood has a point, or had one — at their worst, citations in fiction are annoying, driven by an author’s anxiety to show off what he has read, to check the right boxes.

Q. "Citations serve a dual purpose that seems at once complementary and conflicting." Which of the following best captures the reason why the author makes this statement?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Information has never been more accessible or less reliable. So we are advised to check our sources carefully. There is so much talk of “fake news” that the term has entirely lost meaning. At school, we are taught to avoid Wikipedia, or at the very least never admit to using it in our citations. And most sources on the world wide web have been built without the standardized attributions that scaffold other forms of knowledge dissemination; they are therefore seen as degraded, even as they illuminate.

But it was only relatively recently that academic disciplines designed rigid systems for categorizing and organizing source material at all. Historian Anthony Grafton traces the genealogy of the footnote in an excellent book, which reveals many origin stories. It turns out that footnotes are related to early systems of marginalia, glosses, and annotation that existed in theology, early histories, and Medieval law. The footnote in something like its modern form seems to have been devised in the seventeenth century, and has proliferated since, with increasing standardization and rigor. And yet, Grafton writes, “appearances of uniformity are deceptive. To the inexpert, footnotes look like deep root systems, solid and fixed; to the connoisseur, however, they reveal themselves as anthills, swarming with constructive and combative activity.”

The purpose of citation, broadly speaking, is to give others credit, but it does much more than that. Famously, citations can be the sources of great enmity — a quick dismissal of a rival argument with a “cf.” They can serve a social purpose, as sly thank-yous to friends and mentors. They can perform a kind of box-checking of requisite major works. (As Grafton points out, the omission of these works can itself be a statement.) Attribution, significantly, allows others to check your work, or at least gives the illusion that they could, following a web of sources back to the origins. But perhaps above all else, citations serve a dual purpose that seems at once complementary and conflicting; they acknowledge a debt to a larger body of work while also conferring on oneself a certain kind of erudition and expertise.

Like many systems that appear meticulous, the writing of citations is a subjective art. Never more so than in fiction, where citation is an entirely other kind of animal, not required or even expected, except in the “acknowledgments” page, which is often a who’s who of the publishing world. But in the last two decades, bibliographies and sources cited pages have increasingly cropped up in the backs of novels. “It’s terribly off-putting,” James Wood said of this fad in 2006. “It would be very odd if Thomas Hardy had put at the end of all his books, ‘I’m thankful to the Dorset County Chronicle for dialect books from the 18th century.’ We expect authors to do that work, and I don’t see why we should praise them for that work.” Wood has a point, or had one — at their worst, citations in fiction are annoying, driven by an author’s anxiety to show off what he has read, to check the right boxes.

Q. Which of the following statements about footnotes can be inferred from the second paragraph?

I. According to Grafton, inexperts view footnotes as an immutable system with a singular purpose.

II. Footnotes, in their modern form, have attained a higher degree of standardization and rigour.

III. According to Grafton, experts view footnotes as a system that brews both beneficial and confrontational activities.

IV. Footnotes were an integral feature of Medieval literature, albeit in a form different from modern forms.

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humiliation is more than an individual and subjective feeling. It is an instrument of political power, wielded with intent. In the late 1930s, Soviet show trials used every means to degrade anyone whom Stalin considered a potentially dangerous opponent. National Socialism copied this practice whenever it put ‘enemies of the people’ on trial. On the streets of Vienna in 1938, officials forced Jews to kneel on the pavement and scrub off anti-Nazi graffiti to the laughter of non-Jewish men, women and children. During the Cultural Revolution in China, young activists went out of their way to relentlessly humiliate senior functionaries - a common practice that, to this day, hasn’t been officially reprimanded or rectified.

Liberal democracies, especially after the Second World War, have taken issue with these practices. We like to believe that we have largely eradicated such politics from our societies. Compared with totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, this belief might seem justified. Yet we’re still a far cry from being ‘decent societies’ whose members and institutions, in the philosopher Avishai Margalit’s terms, ‘do not humiliate people’, but respect their dignity. Although construction of the road to decency began as early as around 1800, it was - and remains - paved with obstacles and exceptions.

Mass opposition to the politics of humiliation began from the early 19th century in Europe, as lower-class people increasingly objected to disrespectful treatment. Servants, journeymen and factory workers alike used the language of honour and concepts of personal and social self-worth - previously monopolised by the nobility and upper-middle classes - to demand that they not be verbally and physically insulted by employers and overseers.

This social change was enabled and supported by a new type of honour that followed the invention of ‘citizens’ (rather than subjects) in democratising societies. Citizens who carried political rights and duties were also seen as possessing civic honour. Traditionally, social honour had been stratified according to status and rank, but now civic honour pertained to each and every citizen, and this helped to raise their self-esteem and self-consciousness. Consequently, humiliation, and other demonstrations of the alleged inferiority of others, was no longer considered a legitimate means by which to exert power over one’s fellow citizens.

Historically then, humiliation could be felt - and objected to - only once the notion of equal citizenship and human dignity entered political discourse and practice. As long as society subscribed to the notion that some individuals are fundamentally superior to others, people had a hard time feeling humiliated. They might feel treated unfairly, and rebel. But they wouldn’t perceive such treatment as humiliating, per se. Humiliation can be experienced only when the victims consider themselves on a par with the perpetrator - not in terms of actual power, but in terms of rights and dignity. This explains the surge of libel suits in Europe during the 19th century: they reflected the democratised sense of honour in societies that had granted and institutionalised equal rights after the French Revolution (even in countries that didn’t have a revolution).

The evolution of the legal system in Western nations serves as both a gauge of, and an active participant in, these developments. From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, public shaming was used widely as a supplementary punishment for men and women sentenced for unlawful acts.

Q. Which of the following is true based on the passage?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humiliation is more than an individual and subjective feeling. It is an instrument of political power, wielded with intent. In the late 1930s, Soviet show trials used every means to degrade anyone whom Stalin considered a potentially dangerous opponent. National Socialism copied this practice whenever it put ‘enemies of the people’ on trial. On the streets of Vienna in 1938, officials forced Jews to kneel on the pavement and scrub off anti-Nazi graffiti to the laughter of non-Jewish men, women and children. During the Cultural Revolution in China, young activists went out of their way to relentlessly humiliate senior functionaries - a common practice that, to this day, hasn’t been officially reprimanded or rectified.

Liberal democracies, especially after the Second World War, have taken issue with these practices. We like to believe that we have largely eradicated such politics from our societies. Compared with totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, this belief might seem justified. Yet we’re still a far cry from being ‘decent societies’ whose members and institutions, in the philosopher Avishai Margalit’s terms, ‘do not humiliate people’, but respect their dignity. Although construction of the road to decency began as early as around 1800, it was - and remains - paved with obstacles and exceptions.

Mass opposition to the politics of humiliation began from the early 19th century in Europe, as lower-class people increasingly objected to disrespectful treatment. Servants, journeymen and factory workers alike used the language of honour and concepts of personal and social self-worth - previously monopolised by the nobility and upper-middle classes - to demand that they not be verbally and physically insulted by employers and overseers.

This social change was enabled and supported by a new type of honour that followed the invention of ‘citizens’ (rather than subjects) in democratising societies. Citizens who carried political rights and duties were also seen as possessing civic honour. Traditionally, social honour had been stratified according to status and rank, but now civic honour pertained to each and every citizen, and this helped to raise their self-esteem and self-consciousness. Consequently, humiliation, and other demonstrations of the alleged inferiority of others, was no longer considered a legitimate means by which to exert power over one’s fellow citizens.

Historically then, humiliation could be felt - and objected to - only once the notion of equal citizenship and human dignity entered political discourse and practice. As long as society subscribed to the notion that some individuals are fundamentally superior to others, people had a hard time feeling humiliated. They might feel treated unfairly, and rebel. But they wouldn’t perceive such treatment as humiliating, per se. Humiliation can be experienced only when the victims consider themselves on a par with the perpetrator - not in terms of actual power, but in terms of rights and dignity. This explains the surge of libel suits in Europe during the 19th century: they reflected the democratised sense of honour in societies that had granted and institutionalised equal rights after the French Revolution (even in countries that didn’t have a revolution).

The evolution of the legal system in Western nations serves as both a gauge of, and an active participant in, these developments. From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, public shaming was used widely as a supplementary punishment for men and women sentenced for unlawful acts.

Q. Why does the author feel that humiliation could be felt only after the entrance of the notion of equal citizenship and human dignity in political discourse?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humiliation is more than an individual and subjective feeling. It is an instrument of political power, wielded with intent. In the late 1930s, Soviet show trials used every means to degrade anyone whom Stalin considered a potentially dangerous opponent. National Socialism copied this practice whenever it put ‘enemies of the people’ on trial. On the streets of Vienna in 1938, officials forced Jews to kneel on the pavement and scrub off anti-Nazi graffiti to the laughter of non-Jewish men, women and children. During the Cultural Revolution in China, young activists went out of their way to relentlessly humiliate senior functionaries - a common practice that, to this day, hasn’t been officially reprimanded or rectified.

Liberal democracies, especially after the Second World War, have taken issue with these practices. We like to believe that we have largely eradicated such politics from our societies. Compared with totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, this belief might seem justified. Yet we’re still a far cry from being ‘decent societies’ whose members and institutions, in the philosopher Avishai Margalit’s terms, ‘do not humiliate people’, but respect their dignity. Although construction of the road to decency began as early as around 1800, it was - and remains - paved with obstacles and exceptions.

Mass opposition to the politics of humiliation began from the early 19th century in Europe, as lower-class people increasingly objected to disrespectful treatment. Servants, journeymen and factory workers alike used the language of honour and concepts of personal and social self-worth - previously monopolised by the nobility and upper-middle classes - to demand that they not be verbally and physically insulted by employers and overseers.

This social change was enabled and supported by a new type of honour that followed the invention of ‘citizens’ (rather than subjects) in democratising societies. Citizens who carried political rights and duties were also seen as possessing civic honour. Traditionally, social honour had been stratified according to status and rank, but now civic honour pertained to each and every citizen, and this helped to raise their self-esteem and self-consciousness. Consequently, humiliation, and other demonstrations of the alleged inferiority of others, was no longer considered a legitimate means by which to exert power over one’s fellow citizens.

Historically then, humiliation could be felt - and objected to - only once the notion of equal citizenship and human dignity entered political discourse and practice. As long as society subscribed to the notion that some individuals are fundamentally superior to others, people had a hard time feeling humiliated. They might feel treated unfairly, and rebel. But they wouldn’t perceive such treatment as humiliating, per se. Humiliation can be experienced only when the victims consider themselves on a par with the perpetrator - not in terms of actual power, but in terms of rights and dignity. This explains the surge of libel suits in Europe during the 19th century: they reflected the democratised sense of honour in societies that had granted and institutionalised equal rights after the French Revolution (even in countries that didn’t have a revolution).

The evolution of the legal system in Western nations serves as both a gauge of, and an active participant in, these developments. From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, public shaming was used widely as a supplementary punishment for men and women sentenced for unlawful acts.

Q. Which of the following topics would be a likely continuation of the given discussion?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humiliation is more than an individual and subjective feeling. It is an instrument of political power, wielded with intent. In the late 1930s, Soviet show trials used every means to degrade anyone whom Stalin considered a potentially dangerous opponent. National Socialism copied this practice whenever it put ‘enemies of the people’ on trial. On the streets of Vienna in 1938, officials forced Jews to kneel on the pavement and scrub off anti-Nazi graffiti to the laughter of non-Jewish men, women and children. During the Cultural Revolution in China, young activists went out of their way to relentlessly humiliate senior functionaries - a common practice that, to this day, hasn’t been officially reprimanded or rectified.

Liberal democracies, especially after the Second World War, have taken issue with these practices. We like to believe that we have largely eradicated such politics from our societies. Compared with totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, this belief might seem justified. Yet we’re still a far cry from being ‘decent societies’ whose members and institutions, in the philosopher Avishai Margalit’s terms, ‘do not humiliate people’, but respect their dignity. Although construction of the road to decency began as early as around 1800, it was - and remains - paved with obstacles and exceptions.

Mass opposition to the politics of humiliation began from the early 19th century in Europe, as lower-class people increasingly objected to disrespectful treatment. Servants, journeymen and factory workers alike used the language of honour and concepts of personal and social self-worth - previously monopolised by the nobility and upper-middle classes - to demand that they not be verbally and physically insulted by employers and overseers.

This social change was enabled and supported by a new type of honour that followed the invention of ‘citizens’ (rather than subjects) in democratising societies. Citizens who carried political rights and duties were also seen as possessing civic honour. Traditionally, social honour had been stratified according to status and rank, but now civic honour pertained to each and every citizen, and this helped to raise their self-esteem and self-consciousness. Consequently, humiliation, and other demonstrations of the alleged inferiority of others, was no longer considered a legitimate means by which to exert power over one’s fellow citizens.

Historically then, humiliation could be felt - and objected to - only once the notion of equal citizenship and human dignity entered political discourse and practice. As long as society subscribed to the notion that some individuals are fundamentally superior to others, people had a hard time feeling humiliated. They might feel treated unfairly, and rebel. But they wouldn’t perceive such treatment as humiliating, per se. Humiliation can be experienced only when the victims consider themselves on a par with the perpetrator - not in terms of actual power, but in terms of rights and dignity. This explains the surge of libel suits in Europe during the 19th century: they reflected the democratised sense of honour in societies that had granted and institutionalised equal rights after the French Revolution (even in countries that didn’t have a revolution).

The evolution of the legal system in Western nations serves as both a gauge of, and an active participant in, these developments. From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, public shaming was used widely as a supplementary punishment for men and women sentenced for unlawful acts.

Q. Why does the author cite the example of the Soviet, National Socialism and the Cultural Revolution in China?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humans are strange. For a global species, we’re not particularly genetically diverse, thanks in part to how our ancient roaming explorations caused “founder effects” and “bottleneck events” that restricted our ancestral gene pool. We also have a truly outsize impact on the planetary environment without much in the way of natural attrition to trim our influence.

But the strangest thing of all is how we generate, exploit, and propagate information that is not encoded in our heritable genetic material, yet travels with us through time and space. Not only is much of that information represented in purely symbolic forms—alphabets, languages, binary codes—it is also represented in each brick, alloy, machine, and structure we build from the materials around us. Even the symbolic stuff is instantiated in some material form or the other, whether as ink on pages or electrical charges in nanoscale pieces of silicon. Altogether, this “dataome” has become an integral part of our existence. In fact, it may have always been an integral, and essential, part of our existence since our species of hominins became more and more distinct some 200,000 years ago.

For example, let’s consider our planetary impact. Today we can look at our species’ energy use and see that of the roughly six to seven terawatts of average global electricity production, about 3 percent to 4 percent is gobbled up by our digital electronics, in computing, storing and moving information. That might not sound too bad—except the growth trend of our digitized informational world is such that it requires approximately 40 percent more power every year. Even allowing for improvements in computational efficiency and power generation, this points to a world in some 20 years where all of the energy we currently generate in electricity will be consumed by digital electronics alone.

And that’s just one facet of the energy demands of the human dataome. We still print onto paper, and the energy cost of a single page is the equivalent of burning five grams of high-quality coal. Digital devices, from microprocessors to hard drives, are also extraordinarily demanding in terms of their production, owing to the deep repurposing of matter that is required. We literally fight against the second law of thermodynamics to forge these exquisitely ordered, restricted, low-entropy structures out of raw materials that are decidedly high-entropy in their messy natural states. It is hard to see where this informational tsunami slows or ends.

Our dataome looks like a distinct, although entirely symbiotic phenomenon. Homo sapiens arguably only exists as a truly unique species because of our coevolution with a wealth of externalized information; starting from languages held only in neuronal structures through many generations, to our tools and abstractions on pottery and cave walls, all the way to today’s online world.

But symbiosis implies that all parties have their own interests to consider as well. Seeing ourselves this way opens the door to asking whether we’re calling all the shots. After all, in a gene-centered view of biology, all living things are simply temporary vehicles for the propagation and survival of information. In that sense the dataome is no different, and exactly how information survives is less important than the fact that it can do so. Once that information and its algorithmic underpinnings are in place in the world, it will keep going forever if it can.

Q. The author calls humans 'strange' for all of the following reasons, EXCEPT

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humans are strange. For a global species, we’re not particularly genetically diverse, thanks in part to how our ancient roaming explorations caused “founder effects” and “bottleneck events” that restricted our ancestral gene pool. We also have a truly outsize impact on the planetary environment without much in the way of natural attrition to trim our influence.

But the strangest thing of all is how we generate, exploit, and propagate information that is not encoded in our heritable genetic material, yet travels with us through time and space. Not only is much of that information represented in purely symbolic forms—alphabets, languages, binary codes—it is also represented in each brick, alloy, machine, and structure we build from the materials around us. Even the symbolic stuff is instantiated in some material form or the other, whether as ink on pages or electrical charges in nanoscale pieces of silicon. Altogether, this “dataome” has become an integral part of our existence. In fact, it may have always been an integral, and essential, part of our existence since our species of hominins became more and more distinct some 200,000 years ago.

For example, let’s consider our planetary impact. Today we can look at our species’ energy use and see that of the roughly six to seven terawatts of average global electricity production, about 3 percent to 4 percent is gobbled up by our digital electronics, in computing, storing and moving information. That might not sound too bad—except the growth trend of our digitized informational world is such that it requires approximately 40 percent more power every year. Even allowing for improvements in computational efficiency and power generation, this points to a world in some 20 years where all of the energy we currently generate in electricity will be consumed by digital electronics alone.

And that’s just one facet of the energy demands of the human dataome. We still print onto paper, and the energy cost of a single page is the equivalent of burning five grams of high-quality coal. Digital devices, from microprocessors to hard drives, are also extraordinarily demanding in terms of their production, owing to the deep repurposing of matter that is required. We literally fight against the second law of thermodynamics to forge these exquisitely ordered, restricted, low-entropy structures out of raw materials that are decidedly high-entropy in their messy natural states. It is hard to see where this informational tsunami slows or ends.

Our dataome looks like a distinct, although entirely symbiotic phenomenon. Homo sapiens arguably only exists as a truly unique species because of our coevolution with a wealth of externalized information; starting from languages held only in neuronal structures through many generations, to our tools and abstractions on pottery and cave walls, all the way to today’s online world.

But symbiosis implies that all parties have their own interests to consider as well. Seeing ourselves this way opens the door to asking whether we’re calling all the shots. After all, in a gene-centered view of biology, all living things are simply temporary vehicles for the propagation and survival of information. In that sense the dataome is no different, and exactly how information survives is less important than the fact that it can do so. Once that information and its algorithmic underpinnings are in place in the world, it will keep going forever if it can.

Q. According to the author, which of the following reason makes humans a truly unique species?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humans are strange. For a global species, we’re not particularly genetically diverse, thanks in part to how our ancient roaming explorations caused “founder effects” and “bottleneck events” that restricted our ancestral gene pool. We also have a truly outsize impact on the planetary environment without much in the way of natural attrition to trim our influence.

But the strangest thing of all is how we generate, exploit, and propagate information that is not encoded in our heritable genetic material, yet travels with us through time and space. Not only is much of that information represented in purely symbolic forms—alphabets, languages, binary codes—it is also represented in each brick, alloy, machine, and structure we build from the materials around us. Even the symbolic stuff is instantiated in some material form or the other, whether as ink on pages or electrical charges in nanoscale pieces of silicon. Altogether, this “dataome” has become an integral part of our existence. In fact, it may have always been an integral, and essential, part of our existence since our species of hominins became more and more distinct some 200,000 years ago.

For example, let’s consider our planetary impact. Today we can look at our species’ energy use and see that of the roughly six to seven terawatts of average global electricity production, about 3 percent to 4 percent is gobbled up by our digital electronics, in computing, storing and moving information. That might not sound too bad—except the growth trend of our digitized informational world is such that it requires approximately 40 percent more power every year. Even allowing for improvements in computational efficiency and power generation, this points to a world in some 20 years where all of the energy we currently generate in electricity will be consumed by digital electronics alone.

And that’s just one facet of the energy demands of the human dataome. We still print onto paper, and the energy cost of a single page is the equivalent of burning five grams of high-quality coal. Digital devices, from microprocessors to hard drives, are also extraordinarily demanding in terms of their production, owing to the deep repurposing of matter that is required. We literally fight against the second law of thermodynamics to forge these exquisitely ordered, restricted, low-entropy structures out of raw materials that are decidedly high-entropy in their messy natural states. It is hard to see where this informational tsunami slows or ends.

Our dataome looks like a distinct, although entirely symbiotic phenomenon. Homo sapiens arguably only exists as a truly unique species because of our coevolution with a wealth of externalized information; starting from languages held only in neuronal structures through many generations, to our tools and abstractions on pottery and cave walls, all the way to today’s online world.

But symbiosis implies that all parties have their own interests to consider as well. Seeing ourselves this way opens the door to asking whether we’re calling all the shots. After all, in a gene-centered view of biology, all living things are simply temporary vehicles for the propagation and survival of information. In that sense the dataome is no different, and exactly how information survives is less important than the fact that it can do so. Once that information and its algorithmic underpinnings are in place in the world, it will keep going forever if it can.

Q. Which of the following best captures the central idea discussed in the last paragraph?

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions that follow:

Humans are strange. For a global species, we’re not particularly genetically diverse, thanks in part to how our ancient roaming explorations caused “founder effects” and “bottleneck events” that restricted our ancestral gene pool. We also have a truly outsize impact on the planetary environment without much in the way of natural attrition to trim our influence.

But the strangest thing of all is how we generate, exploit, and propagate information that is not encoded in our heritable genetic material, yet travels with us through time and space. Not only is much of that information represented in purely symbolic forms—alphabets, languages, binary codes—it is also represented in each brick, alloy, machine, and structure we build from the materials around us. Even the symbolic stuff is instantiated in some material form or the other, whether as ink on pages or electrical charges in nanoscale pieces of silicon. Altogether, this “dataome” has become an integral part of our existence. In fact, it may have always been an integral, and essential, part of our existence since our species of hominins became more and more distinct some 200,000 years ago.

For example, let’s consider our planetary impact. Today we can look at our species’ energy use and see that of the roughly six to seven terawatts of average global electricity production, about 3 percent to 4 percent is gobbled up by our digital electronics, in computing, storing and moving information. That might not sound too bad—except the growth trend of our digitized informational world is such that it requires approximately 40 percent more power every year. Even allowing for improvements in computational efficiency and power generation, this points to a world in some 20 years where all of the energy we currently generate in electricity will be consumed by digital electronics alone.

And that’s just one facet of the energy demands of the human dataome. We still print onto paper, and the energy cost of a single page is the equivalent of burning five grams of high-quality coal. Digital devices, from microprocessors to hard drives, are also extraordinarily demanding in terms of their production, owing to the deep repurposing of matter that is required. We literally fight against the second law of thermodynamics to forge these exquisitely ordered, restricted, low-entropy structures out of raw materials that are decidedly high-entropy in their messy natural states. It is hard to see where this informational tsunami slows or ends.

Our dataome looks like a distinct, although entirely symbiotic phenomenon. Homo sapiens arguably only exists as a truly unique species because of our coevolution with a wealth of externalized information; starting from languages held only in neuronal structures through many generations, to our tools and abstractions on pottery and cave walls, all the way to today’s online world.

But symbiosis implies that all parties have their own interests to consider as well. Seeing ourselves this way opens the door to asking whether we’re calling all the shots. After all, in a gene-centered view of biology, all living things are simply temporary vehicles for the propagation and survival of information. In that sense the dataome is no different, and exactly how information survives is less important than the fact that it can do so. Once that information and its algorithmic underpinnings are in place in the world, it will keep going forever if it can.

Q. Which of the following can be inferred from the passage?

The passage given below is followed by four summaries. Choose the option that best captures the author’s position.

What is beauty? Beauty is that which gives aesthetic pleasure. Beauty is both subjective and objective—subjective because it is “in the eye of the beholder” but objective in that “pleasure” is something you either experience or you do not. If a building isn’t giving people pleasure to look at, then it is not beautiful, because beautiful things are things that you want to keep looking at because seeing them brings joy. The fact that beauty is both subjective and objective means that a thing can be beautiful to some people and not to others. For instance, contemporary buildings are beautiful to architects, who clearly receive pleasure from looking at them. However, majority of people get more pleasure out of looking at the ancient buildings than the contemporary buildings.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- These observations are informative but do not address fundamental questions about how social-cognitive brain systems develop or why their development might be different for autistic people.

- Accordingly, differences in the development and/or transmissions of information across this distributed social-cognitive brain network may contribute to differences in mentalizing among autistic people.

- Social-cognitive neuroscience tells us that brain systems of the medial frontal cortex, temporal cortex and parietal cortex, as well as reward centres of the brain, enable mentalizing.

- These differences can lead to a range of outcomes, from problems in the capacity to mentalize to alterations in the spontaneous use of mentalizing or the motivation and effort involved in mentalizing during social interactions.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

- As a matter of fact, many of the tools and resources that I used on my missions, such as solar panels and rechargeable storage batteries, are also the answer to our problems here on Earth.

- After seeing the Earth dramatically change from this unique perspective, I firmly believe that solving climate change is the moonshot of the 21st century.

- On my last mission in 2016, only 17 years later, burning and clear-cutting were clearly evident in the region.

- During my first mission, in 1999, to fix the Hubble Space Telescope, I remember passing over South America and being awed by the sheer size of the Amazon rainforest.

Five sentences related to a topic are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out.

- Most of it isn’t thrown off ships, she and her colleagues say, but is dumped carelessly on land or in rivers, mostly in Asia.

- It’s unclear how long it will take for that plastic to completely biodegrade into its constituent molecules.

- No one knows how much unrecycled plastic waste ends up in the ocean, Earth’s last sink.

- It is then blown or washed into the sea.

- But in 2015, Jenna Jambeck, a University of Georgia engineering professor, caught everyone’s attention with a rough estimate: between 5.3 million and 14 million tons each year just from coastal regions.

Five sentences related to a topic are given below. Four of them can be put together to form a meaningful and coherent short paragraph. Identify the odd one out.

- Instead, it was three beluga whales from Marineland, an aquatic park in Ontario, Canada, that were sitting aboard, in special water-filled transport containers.

- Kharabali, Havana and Jetta, three females, were loaded onto flatbed trucks and driven seven miles east on I-95 to Mystic Aquarium in southeast Connecticut.

- There, a crane gently lowered them, one by one, into the medical pool, a separate but connected body of water within the aquarium’s 750,000-gallon beluga pool, called Arctic Coast.

- Two more whales, Havok and Sahara, a male and a female, were sent back to Ontario as part of the exchange agreement.

- A dusty grey C-130 rolled to a stop just as the sun was going down over the tarmac of the Air National Guard Station at the Groton-New London Airport in Connecticut on Friday, and the plane wasn’t carrying its usual haul of utility helicopters or jeeps.

The four sentences (labelled 1, 2, 3, and 4) below, when properly sequenced, would yield a coherent paragraph. Decide on the proper sequencing of the order of the sentences and key in the sequence of the four numbers as your answer:

1. This fragmentation, rather paradoxically, has not yielded the expected liberation of the workforce but has often led to more precarious living conditions.

2. The modern economy, characterized by the gig economy and freelance culture, promised freedom and flexibility compared to traditional 9-to-5 jobs.

3. Herein lies the critical need to reevaluate labor laws and social security systems to address the unique challenges of modern employment landscapes.

4. In the absence of the conventional security nets associated with permanent employment, workers find themselves navigating an uncertain and often unrewarding path.

The passage given below is followed by four alternate summaries. Choose the option that best captures the essence of the passage.

Fossil fuel divestment, a growing movement, urges organizations to withdraw investment from companies involved in extracting fossil fuels. This movement aims to reduce carbon emissions to combat climate change and is a powerful tool for social change. Critics argue that divestment alone won't stop climate change and that it might harm investors’ returns. Proponents, however, see it as a moral and pragmatic stand, forcing the industry to reckon with its role in climate change while paving the way for investment in sustainable energy alternatives.

Totalitarianism is not always operated by diktat. It can be insinuated by suggestion and replication. Dissent does not have to be banned if it is countered by orchestrated mass promo rallies and hypnotizing oratory. Despotic establishments do not need to turn Hitlerian; all they need to do is to let the Reich chemistry work. Self-regulation and self-censorship will click in. Then any dissident who wants to retain his intellectual liberty will find himself thwarted by the general drift of society rather than by active persecution.

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question below.

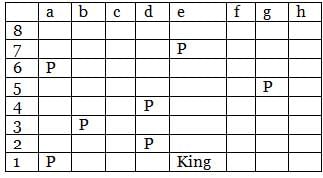

There is a square shaped board similar to chessboard which is having eight rows and eight columns. On this board, rows are numbered 1 to 8 (bottom to top) and the columns are labelled a to h (left to right). On the chessboard, the King is placed at e1. The position of a piece is given by the combination of column and row labels. For example, position e4 means that the piece is in the eth column and the 4th row. In the chessboard, Rook placed anywhere can attack another piece if the piece is present in the same row, or in the same column in any possible 4 directions, provided there is no other piece in the path from the Rook to that piece.

Q. If the King is at the same position and the other pieces are at positions a1, a6, d2, d4, b3, g4 and e7, then which of the following positions of the Rook attacks the maximum number of pieces if there are no other pieces on the board?

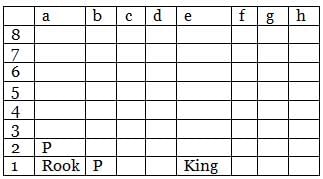

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question below.

There is a square shaped board similar to chessboard which is having eight rows and eight columns. On this board, rows are numbered 1 to 8 (bottom to top) and the columns are labelled a to h (left to right). On the chessboard, the King is placed at e1. The position of a piece is given by the combination of column and row labels. For example, position e4 means that the piece is in the eth column and the 4th row. In the chessboard, Rook placed anywhere can attack another piece if the piece is present in the same row, or in the same column in any possible 4 directions, provided there is no other piece in the path from the Rook to that piece.

Q. Find the minimum number of positions which the Rook can possibly attack irrespective of the placement of other pieces.

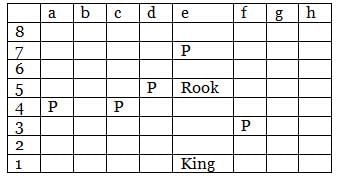

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question below.

There is a square shaped board similar to chessboard which is having eight rows and eight columns. On this board, rows are numbered 1 to 8 (bottom to top) and the columns are labelled a to h (left to right). On the chessboard, the King is placed at e1. The position of a piece is given by the combination of column and row labels. For example, position e4 means that the piece is in the eth column and the 4th row. In the chessboard, Rook placed anywhere can attack another piece if the piece is present in the same row, or in the same column in any possible 4 directions, provided there is no other piece in the path from the Rook to that piece.

Q. If the Rook is at e5, the King remains unmoved and the other pieces are at positions a4, e7, c4, f3, d5 only, then how many of them are under attack by the Rook.

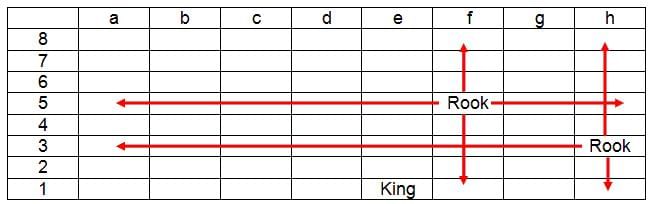

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question below.

There is a square shaped board similar to chessboard which is having eight rows and eight columns. On this board, rows are numbered 1 to 8 (bottom to top) and the columns are labelled a to h (left to right). On the chessboard, the King is placed at e1. The position of a piece is given by the combination of column and row labels. For example, position e4 means that the piece is in the eth column and the 4th row. In the chessboard, Rook placed anywhere can attack another piece if the piece is present in the same row, or in the same column in any possible 4 directions, provided there is no other piece in the path from the Rook to that piece.

Q. Suppose apart from the King there are only two Rooks on the board and are positioned at f5 and h3. In how many positions can another piece be placed on the board such that it is safe from attack by the Rook?

Directions: Read the following information and answer the question below.

There is a square shaped board similar to chessboard which is having eight rows and eight columns. On this board, rows are numbered 1 to 8 (bottom to top) and the columns are labelled a to h (left to right). On the chessboard, the King is placed at e1. The position of a piece is given by the combination of column and row labels. For example, position e4 means that the piece is in the eth column and the 4th row. In the chessboard, Rook placed anywhere can attack another piece if the piece is present in the same row, or in the same column in any possible 4 directions, provided there is no other piece in the path from the Rook to that piece.

Q. If the Rook is positioned anywhere on the board and the King remains unmoved, then at how many maximum positions can the Rook attack?

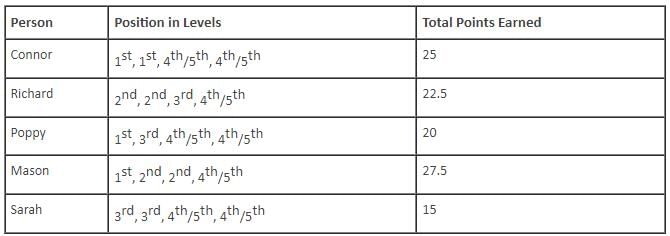

Directions: Read the information given below and answer the question:

Exactly five friends – Connor, Richard, Poppy, Mason and Sarah – were playing a racing game which consists of four levels. In each level, the persons who stood first, second and third were awarded points of 10, 7.5 and 5 respectively, while the other two persons were awarded 2.5 points each.

It is also known that

(1) the total points earned by no two friends in the game were same.

(2) Connor earned 5 more points than Poppy and neither of them earned the highest total points in the game.

(3) Richard, who was last in one of the four levels, earned a total of 22.5 points in the game but he was not first in any level.

(4) one of the five persons was first in more than one level and he did not win the highest points in the game.

(5) Mason was not third in any of the four levels but was first in one of the four levels.

(6) the points that Poppy earned in the game were more than the points that Sarah earned.

Q. Which of the following statements is definitely true?