Agriculture-1 | Geography for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Agriculture in India

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for about 58% of India’s population. The Indian food industry is poised for huge growth, increasing its contribution to the world food trade every year.

- India is the second-largest producer of wheat and rice, the world's major food staples.

- India is currently the world's second-largest producer of several dry fruits, agriculture-based textile raw materials, roots and tuber crops, pulses, farmed fish, eggs, coconut, sugarcane, and numerous vegetables.

Causes of Low Productivity in Indian Agriculture

Various factors responsible for the low productivity of Indian agriculture are:

- Increasing Population: Because of the excessively increasing population, our land resources have been used extensively thereby leading to loss of fertility of the soil.

- Reckless Deforestation: It has led to declining flora so that less humus is being added to the soil through a normal process. Human deficiency is resulting in the increasing soil temperature, and hence making the pre-monsoon cropping more and more difficult. Human deficiency is resulting in the increasing soil temperature, and hence making the pre-monsoon cropping more and more difficult. Human deficiency also causes a reduction in the capacity of soil to hold moisture.

- Increased construction of roads, railways, and canals: They have disturbed the natural drainage system or normal flow of rainwater thus bringing heavy floods. This results in large-scale damage to Kharif crops and considerable late sowing of rabi crops.

- Marginal and sub-marginal lands, which are generally inferior and yield less, are being cultivated due to increasing population pressures.

Causes of WorldWide Land Degradation

Causes of WorldWide Land Degradation

- Recent Land Reforms: As a consequence of recent land reforms, the land is passing (by purchase, lease, or allotment) to classes that have no agricultural traditions and in most cases lack the necessary technical knowledge and, therefore, are inefficient farmers.

- Soil Erosion: Due to soil erosion, growing salinity, aridity, alkalinity, and semi-desert conditions, cultivable land is turning into barren waste.

- Subsistence type of farming: The subsistence type of farming results in a deficit agricultural economy as agriculture remains a low-income occupation that follows low savings, low investment, and low agricultural incomes.

- Uncertain Rainfall: Uncertain and erratic rainfall, unfavorable weather conditions, and pest and diseases of crops reduce crop yields.

- Small, uneconomic, and fragmented holdings make the use of modern methods of cultivation difficult.

- Traditional equipment, inadequacy, and obsolete nature of tools are also contributory factors.

- Lack of organization and leadership in Indian agriculture causes heavy erosion of resourceful talent from agriculture which considerably reduces the capacity of the farming communities to compete and progress.

- Inadequacy of irrigation facilities, lack of and high prices of manures and fertilizers.

- The concentration of land in a few hands, below which are a large number of small and medium cultivators, result in non-utilization of land to its fullest extent

- Restricted storage facilities depress the price in the market, and bad communication and imperfect marketing facilities prevent the realization of a fair price for the produce.

- Inadequacy of non-farm services like provision of cheap credit and the resultant indebtedness and poverty of the peasant as well as lack of marketing facilities restrict improvement in techniques of production.

Reorganization of Indian Agriculture

In India, the agrarian system needs reorganization according to the present-day needs and conditions on improved lines.

Increased agricultural productivity is essential for the following three reasons:

- To supply an economic surplus that can be consumed or used for further production in agriculture or transferred out of agriculture to provide capital for industrial growth and to meet the expanding consumption needs of the urban population.

- To make possible the release of labor and other resources for use in non-agricultural sectors.

- To increase the purchasing power of rural people, expand markets for industrial goods, and help to bring about needed changes in the national income organization.

Improving Productivity in Agriculture

The basic conditions for improving productivity in agriculture, according to FAO are:

- Reasonably more control to be applied on increasing population.

- Stable prices for agricultural products at a remunerative level.

- Adequate marketing facilities.

- Satisfactory system of land tenure.

- Provision of credit on reasonable terms especially to small farmers, for improved methods of production.

- Provision of production requisites (fertilizers, pesticides, improved seeds, etc.) at reasonable prices.

- Provision of education, research, and extension of agro-economic services to spread the knowledge of improved methods of farming.

- The development of sources, by the State, which is beyond the powers of individual farmers, such as large-scale irrigation, land reclamation, or resettlement problems.

- Extension of land use and intensification and utilization of land already in use through improved and scientific methods of cultivation.

- Diversification of farm production i.e., besides cultivation of crops, dairy, poultry, and fishing industries should be developed.

- The above factors will not only help in maintaining but also in developing soil productivity to the highest practicable level thereby stabilizing our agrarian economy and improving the plight of rural India.

The physical resources of soil, water, and climate are sufficient to yield at least double, perhaps more than double the current production with full use of machines, chemicals, sufficient water supply, and a combination of other good management practices.

Soil and Water Conservation

Launched from the very First Plan, soil and water conservation programs are one of the essential inputs for increasing agricultural output in the country.- These programs emphasize on development of technology for problem identification, enactment of appropriate legislation, and constitution of policy coordination bodies.

Objectives of Soil and Water Conservation

- The main objectives of the scheme in operation are:

(i) To slow the process of land erosion and degradation.

(ii) To restore degraded lands to ensure regeneration.

(iii) To improve and ensure the availability of water and soil moisture.

(iv) To create micro-level irrigation through water harvesting.

(v) To enhance internal fertility of soil through organic recycling.

(vi) To enlarge effective productive exploitation zone to the deeper soil profile by adopting mixed and companion farming system.

(vii) To increase aggregate bio-mass production.

(viii) To generate employment through continuous adjustments in optimum land use planning and to ensure collective security against recurring droughts and floods. - Programs sponsored by the Soil and Water Conservation Division at the national level are checking problems like water and wind erosion, degradation through waterlogging, salinity, ravines, torrents, shifting cultivation, coastal sands in addition to declining man-land ratio, increasing and competing demands for land, diversion of arable land and loss of productivity.

- The major central/centrally sponsored schemes have been directed towards checking premature siltation of the multipurpose reservoirs; mitigating the flood hazard in the productive plains; resettling of shifting cultivators, and restoring degraded lands.

Measures Undertaken for Soil & Water Conservation.

- A scheme for soil conservation in the catchments of river valley projects was launched in the Third Five Year Plan to prevent pre-mature siltation of multipurpose reservoirs.

- A centrally sponsored scheme for reclamation of alkali (usar) soils, launched during the Seventh Plan, continues in Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh. The components of the scheme include assured irrigation water, on-farm development works like land leveling, deep plowing, community drainage systems, application of soil amendment, organic manure, etc. An area of 3.36 lakh hectares of land has been reclaimed up to 1993-94.

- A scheme for control of shifting cultivation was implemented with cent percent central assistance in all the seven north-eastern states, Andhra Pradesh and Orissa till 1990-91. From 1991-92 the scheme was transferred to the state sector. The scheme has been revived for the north-eastern states only from 1994-95.

- A scheme of Integrated Watershed Management in the catchments of flood-prone rivers was launched during the Sixth Plan in eight flood-prone rivers of the Gangetic basin covering seven States and Union Territories. The scheme aims at enhancing the ability of the catchment areas to absorb a larger quantity of rainwater, thus reducing erosion, silting, and the consequent fury of floods.

- All India Soil and Land-use Survey Organisation (AISLUSO) with its seven regional/sub-regional centers does catchment delineation and fixing of priorities for watershed development.

- The National Land Use and Conservation Board (NLCB) is concerned primarily with national land-use policy. It coordinates the work of the State Land Use Board (SLUB) in preventing indiscriminate diversion of good agriculture, scientific management of land use, and conservation.

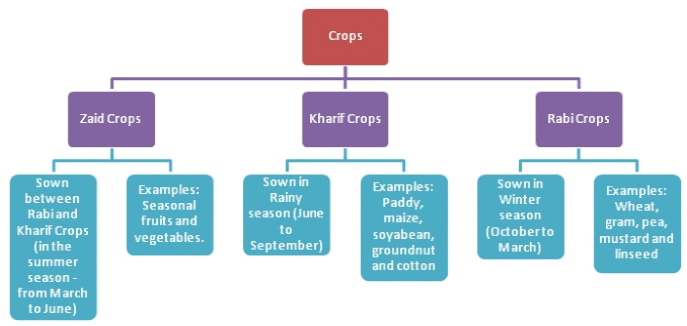

Crop Season

Crop seasons in India are broadly divided into two:

(i) Kharif or the summer/rainy season, in which crops requiring more water are grown.

(ii) Rabi or winter season in which crops requiring less water are grown.

The periodicity of the season usually allows two and in few cases three harvests in a year.

Classification of Crops

Kharif Crops

These crops, which require much water and long hot weather for their growth, are sown (in June or early July) with the commencement of southwest monsoon and are harvested by the end of monsoon or autumn (September/October). The main kharif crops include rice, jowar, maize, cotton, groundnut, jute, hemp, tobacco, bajra, sugarcane, pulses, forage grasses, green vegetables, chilies, groundnuts, lady's finger, etc.

Rabi Crops

These crops, grown in winter, require a relatively cool climate during growth and warm climate during germination of their seeds and maturation. Therefore sowing is done in November and crops are harvested in April-May. The major rabi crops are wheat, gram, and oilseeds like mustard and rapeseed.

Zaid Crops

Besides these two dominant crops, a brief cropping season has been lately introduced in India mainly in irrigated areas where early-maturing crops, called zaid crops, are grown between March and June. The chief zaid crops are urad, moong, melons, watermelons, cucumber, tuber vegetables, etc.

Choose the correct answer from the options given below

A. It is a short duration summer cropping season which begins after the planting of the rabi crops

B. It is a short duration summer cropping season which begins after the harvesting of rabi crops

C. It exists as a well marked cropping season in South India as the temperature variation is very high

D. In northern India's irrigated areas, watermelons, vegetables, and fodder crops are grown in this season

Cropping Pattern

'Cropping Pattern' is the relative proportion of cropped area under various crops in different parts of the country at a particular period of time.

Factors affecting Cropping Pattern

The choice of growing a particular crop in a particular region depends on the following factors:

- General agricultural conditions such as soil, climate, water supply, sub-soil water table, etc.

- Aim of agricultural production, the scale of production, size of holdings, techniques of agriculture, change in market prices, availability of transport, and distance from the market.

- Personal factors like requirements for home and family consumption, meeting cash requirements of the family, meeting feed and fodder needs of the year, for maintaining soil fertility or for green manuring, seed purposes, etc.

Characteristic Features of Cropping Pattern

Some of the characteristic features of cropping pattern in India are:

Amazing variety of crops

In Eastern India, east of 800 east longitude and in the coastal lowlands, especially the western coast, south of Goa, rice is the predominant crop. Tea and jute are the major crops of East India. West of 800 east longitude and north of Surat (where rainfall is below 100 cm) jowar, bajra, pulses, cotton, and groundnut are the chief crops in the plateau; and wheat including pulses, gram, cotton, oilseeds, jowar, bajra and in irrigated areas sugarcane are all grown in the alluvial plains of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Haryana.

The preponderance of food over non-food crops

About three-fourths of the total cropped area is under food crops. Among the food crops the chief crops grown are rice, wheat, and millets with some maize and barley, occupying about 70 percent of net sown area. Pulses come next in the area followed by oilseeds. The substantial area also lies under tobacco, potatoes, fruits and vegetables, tea, coffee, rubber and coconut but their share in the total cropped area is relatively small.

The stone fruits, apricots, peaches, grapes, melons are found in the north in mountains and uplands.

Intensity of Cropping

- One of the methods to increase total food production is to increase the net cropped area. However, after a certain limit, it is impossible to increase the net cropped area. Therefore the only way left to increase the total food production is to increase the intensity of cropping and crop yields.

- The intensity of cropping means growing a number of crops on a field in one agricultural year. Suppose a farmer has 5 hectares of cultivable land on which he grows a crop during the Kharif season. After harvesting the Kharif crop he again grows a crop during rabi season on the same land but on 2 hectares area only. This means the farmer obtained the crops from a total of 7 hectares area (from 5 hectares are during Kharif and from 2 hectares area during rabi season) though in fact, he had only 5 hectares of land. Had he sown only one crop during Kharif season on the 5-hectare land then the index of cropping would have been 100 percent but in the aforementioned example index of cropping will be 140 percent.

- In fact intensity of cropping reflects the efficiency of land use. The index of cropping is 126 percent for India as a whole but varies considerably with the states and districts.

- The index of cropping reached a maximum of 160 percent during 1983-84 in Punjab. It is minimum in the dry areas such as Maharashtra, Karnataka, Rajasthan, and Gujarat varying between 115, 118, 116, and 109 percent respectively. The main factor that affects the intensity of cropping includes irrigation, fertilizers, a variety of seeds (early maturing and high yielding), selective mechanization such as the use of tractors, pumping sets and seed drills, and plant protection using herbicide, pesticide and insecticide, etc.

- Greater cropping intensity and increase in the proportion of area sown more than once have achieved stable and higher crop yields in many parts of the country.

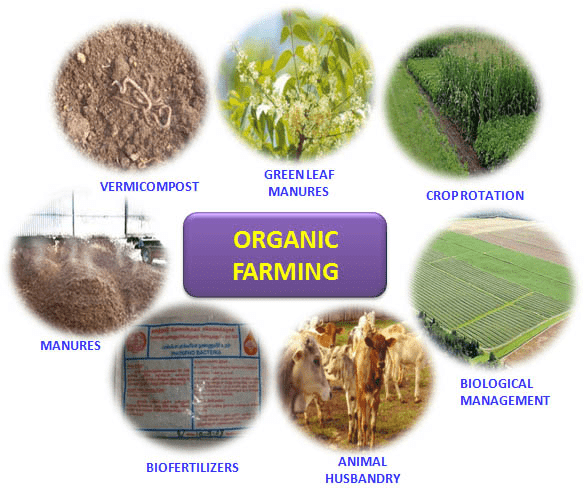

Organic Farming

Organic farming is natural farming which is based on the principles of no plowing, no fertilizer or prepared compost, no weeding or tillage, and no pest control but only sowing and harvesting and increasing the fertility of soil through biological residues.

In its developed form, it seeks to rely on biological processes to obtain high quality and yields which are often as good as those achieved using modern agricultural techniques.

Advantages of Organic Farming

(i) Reduced pollution

(ii) Less energy is used

(iii) Since no chemical pesticides, hormones, and fertilizers are used, residues from these substances are no longer a danger

(iv) Less mechanization is used

(v) Less occurrence of pest incidence due to absence of fertilizers and pesticides,

(vi) Yields on par with modern farming

(vii) Food fetches more price than that produced from modern farming; and

(viii) Is an excellent method of sustainable agriculture.

Problems of Organic Farming

- Land resources can move freely from organic farming to conventional farming but the movement is not free in the reverse direction.

- Loss of initial crop, while changing over to organic farming, particularly, if done quickly.

- Biological controls may have been weakened or destroyed by chemicals, which may take three to four years for residues to lose their effect.

- Farmers may be afraid to enter the new system of farming without government support.

Significance of Organic Farming

- The big challenge we are facing in agriculture today is the unsustainability of the present (modern) system of agriculture.

- The nature and extent of the unsustainability of modern agriculture can be viewed considering the following consequences. Intensive cultivation of land without conservation of soil structure would lead ultimately to the expansion of deserts.

- Irrigation without proper drainage would result in soils getting alkaline or saline.

- Indiscriminate use of pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides could cause adverse changes in biological balance as well as lead to an increase in the incidence of cancer and other diseases through toxic residues present in the grain or the edible parts.

- Unscientific tapping of underground water would lead to the rapid exhaustion of this resource left to us through ages of natural farming. The rapid replacement of a number of locally adapted varieties with one or two high-yielding varieties in the large contiguous areas would result in the spread of serious diseases capable of wiping out entire crops.

- The aforementioned realities clearly indicate the significance of organic farming–the only way for sustainable agriculture–as the only alternative to unsustainable modern agriculture practice.

- Organic farming promises a better and balanced environment, better food, and higher living standard to the masses in India. It also promises a better long-term future of agriculture, because of low-cost agricultural development.

Shifting Cultivation

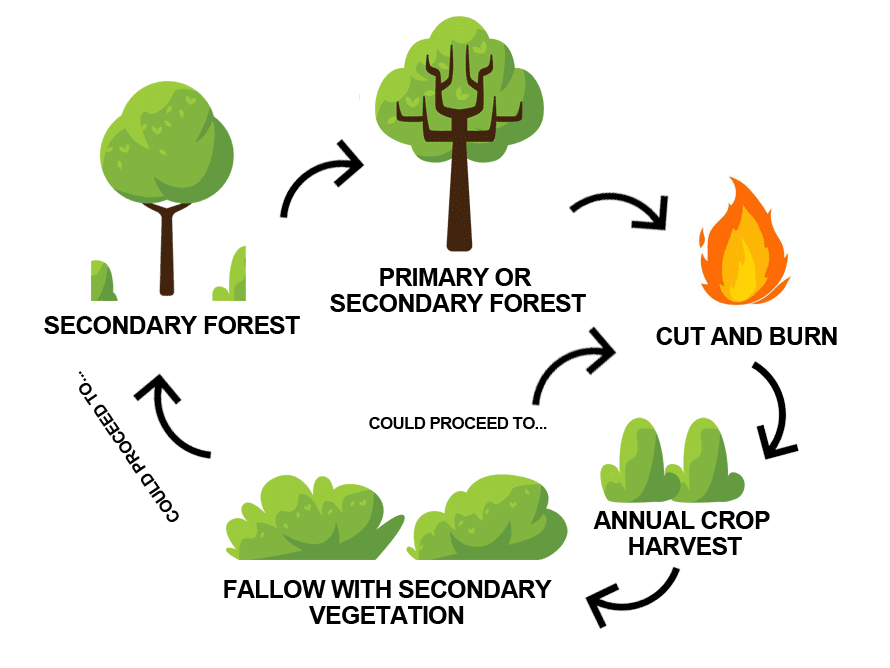

It is an agricultural system in which a patch of forest is cleared of trees and most vegetation, to be cultivated for few years until the fertility is seriously reduced. The site is then abandoned and a fresh site is cleared elsewhere.

Cleared vegetation is usually burned (slash and burn) and crops planted in the fertile ashes.

Shifting Cultivation

Shifting Cultivation

- In India, variously known as jhum in Assam, ponam in Kerala, podu in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa, ewar, mashan, penda and Beera in different parts of Madhya Pradesh, shifting cultivation is practised by tribal people over an estimated area of about 54 lak hectares, about 20 lakh hectares being cleared by them (totaling more than 100 tribes) by felling and burning the forests every year.

- Major crops grown are dry paddy, buckwheat, maize, small millets, and sometimes even tobacco and sugarcane. Shifting cultivation is prevalent in the forest areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and Andhra Pradesh.

- This way of exploiting rich forest soils is responsible for large-scale removal of forests and soil erosion on hill slopes, and floods and the devastation due to them in the plains below.

- A check on this destruction of national wealth, therefore, is very essential. Considering the socio-economic aspect of this problem we must not only put a check on this type of cultivation but also educate the tribal people, who practice it, about improved methods of agriculture.

Dryland Farming

Approximately 70 percent of the 141.73 million hectares of arable land in India, i.e. nearly 92 million hectares of land is rainfed and depends on natural precipitation, which is often erratic and unpredictable, for crop production.

Even after total irrigation potential is realized by the close of the century (2000 A.D.) there will be nearly 50 percent of the total arable land will continue to be rainfed.

The bulk of the crops like rice, jowar, bajra, other millets, pulses, oilseeds, and cotton are grown in this area under rainfed conditions.

Dryland farmingRainfed agriculture or dryland farming is solely dependent on rainwater at any crop stage. It is synonymous with non-irrigated agriculture and refers to a wide range of patterns from arid to humid conditions. Rainfed agriculture is of two types –

(i) Rainfed wetland farming is undertaken where rainfall is adequate and fairly well distributed during the crop season.

(ii) Rainfed dryland farming where agricultural activity is under low rainfall conditions which is erratic as well as concentrated in a short period. The water balance is frequently negative and moisture conservation is very essential here as compared to drainage of excess rainwater in the rainfed wetlands.

Problems of Dryland Farming

Rainfed agriculture is characterized by erratic and unpredictable rainfall. This results in wide fluctuations in the production performance of crops in these areas. The soils of these areas are affected by erosion which results in poor moisture-holding capacity besides impoverishment of soil in terms of nutrients. This makes the soil less productive and greater investment in terms of conservation and improvements.

A wide variety of crops are grown in these areas which are directly dependent on the availability of a number of growing days. These are characterized by low production and low productivity.

Measures to Improve Production & Productivity

Some of the improvements that have been introduced to increase the yield and production in the rainfed areas include soil and rainwater management; crop management; efficient cropping systems; and adoption of alternative land-use systems such as the adoption of ecologically benign, economically viable, operationally feasible and socially acceptable cropping systems involving the cultivation of high yielding predominant crops of different regions. The government has given high priority to the development of dryland areas and, therefore, several programs and projects have been launched for the utilization of the potential of these areas.

- Realizing the project requirement of about 240 mt of annual food production by 2000 AD and to smoothen out fluctuation in annual production.

- Reducing regional disparities between irrigated and vast rainfed areas.

- Restoring ecological balance by greening rainfed areas through the appropriate mixture to trees, shrubs, and grasses; and

- Generating employment for rural masses and reducing large-scale migration from rural areas to already congested cities and towns.

- A holistic approach for integrated farming system development on a watershed basis in rainfed areas is the main plank of the development activities under the National Watershed Development Project for Rainfed Areas (NWDPRA) initiated in the Eighth Plan.

Arid Zone

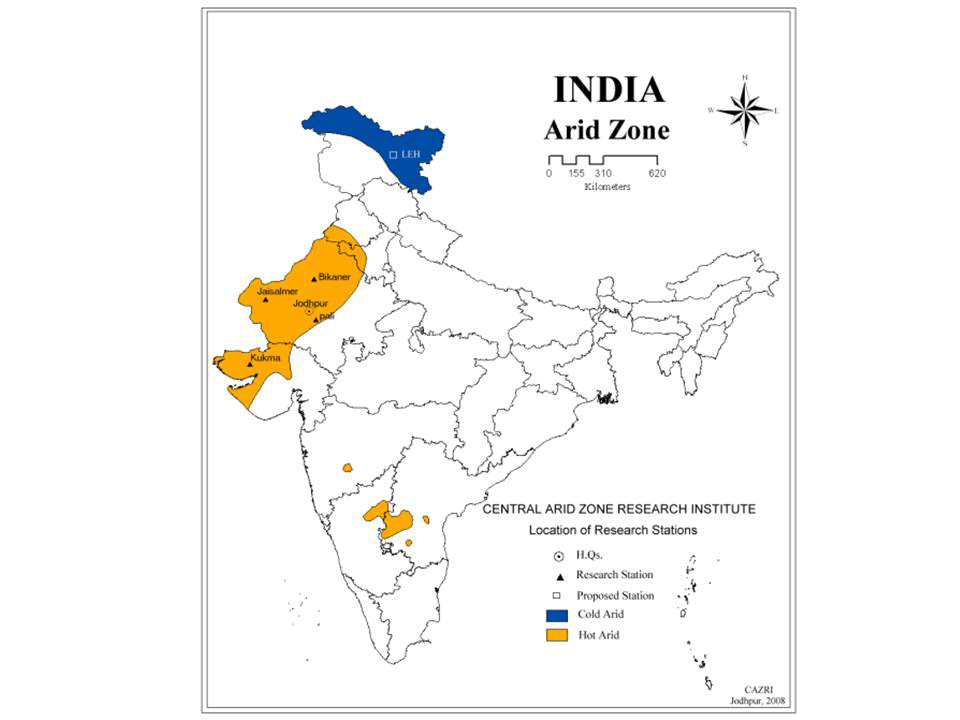

Arid zone are those regions which have very low annual rainfall, dry climate, high rate of evaporation and always have water deficiency.

In India, arid regions are of two types: hot arid region and cold arid region.

(i) The hot arid region of India is spread over 31.7 million hectares–61% of it is in west Rajasthan and 20% in Gujarat, the rest being in Haryana, Punjab, and Karnataka. The rainfall varies from 0-40 cm.

(ii) The cold arid region is spread over Ladakh in J & K. The rainfall varies from 0.2 - 4cm. The agricultural season in the region is limited to about five months a year due to high aridity and low temperature.

In the hot arid zones, the hot climate and shortage of water hamper agriculture. Only some drought-resistant varieties of crops can be grown through cautious and scientific management of scarce groundwater. Fruits like ber and pomegranate and fuelwood trees like acacia can be grown here. However, animal husbandry involving sheep, goats, camels is best suited for this region.

In the cold arid region, the problem is the same. Some cereals, oilseeds, and fodder crops that mature in a short period and withstand severe cold can be cultivated. Yak and pashmina goats can be best reared in these regions.

Recent Developments

In recent years, Indian agriculture has undergone significant transformations driven by technological innovations, policy reforms, and responses to global challenges. This section highlights the key developments up to 2025 that have shaped the agricultural landscape in India, ensuring that the sector remains a vital component of the nation's economy and food security.

Technological Advancements

- Drones and AI: The adoption of drones for crop monitoring, precision farming, and pesticide application has become widespread. AI-powered tools are now integral for yield prediction, soil health assessment, and efficient resource management, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions.

- Blockchain Technology: Blockchain is increasingly used to enhance transparency and traceability in agricultural supply chains. This technology helps in verifying the authenticity of organic produce and ensuring fair trade practices.

Government Policies and Schemes

- PM-KISAN Scheme (2019): This flagship scheme provides direct income support of ₹6,000 annually to small and marginal farmers, aiding in their financial stability.

- Agriculture Infrastructure Fund (2020): Aimed at strengthening farm infrastructure, this fund supports the development of cold storage facilities, warehouses, and processing units, reducing post-harvest losses.

- MSP Updates: The Minimum Support Price system has seen revisions to ensure better remuneration for farmers, with ongoing debates focusing on making it more inclusive and effective.

Climate Change and Adaptation

- Climate-Smart Agriculture: Farmers are increasingly adopting climate-resilient practices such as drought-tolerant crop varieties, advanced irrigation techniques like drip and sprinkler systems, and agroforestry to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

- Extreme Weather Impacts: The rising frequency of extreme weather events, including floods and droughts, has necessitated the development of robust disaster management strategies and crop insurance schemes to protect farmers' livelihoods.

Global Trade and International Agreements

- Export Policies: India's Agriculture Export Policy has been updated to promote the export of high-value agricultural products, with a focus on organic and processed foods.

- WTO Developments: Ongoing negotiations at the World Trade Organization have influenced India's agricultural policies, particularly concerning subsidies and market access, impacting the competitiveness of Indian farmers globally.

Impact of COVID-19

- Supply Chain Disruptions: The pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in agricultural supply chains, leading to labor shortages, transportation bottlenecks, and market access issues. These challenges prompted the government to implement measures to ensure the smooth flow of agricultural goods.

- Government Measures: Initiatives like the Atmanirbhar Bharat package provided financial relief and support to farmers, including credit facilities and market linkages, to mitigate the pandemic's adverse effects.

Sustainable Agriculture and Organic Farming

- Organic Farming Growth: There has been a significant increase in organic farming, supported by government incentives, certification programs, and growing consumer demand for organic produce both domestically and internationally.

- Regenerative Agriculture: Practices such as agroforestry, cover cropping, and soil carbon sequestration are being promoted to enhance soil health and biodiversity, contributing to long-term sustainability.

Updated Statistics and Data

As of 2025, India's agricultural sector has achieved remarkable milestones. The production of major crops has increased, with rice output reaching X million tonnes and wheat production at Y million tonnes. The sector's contribution to India's GDP stands at Z%, underscoring its continued significance in the economy. Additionally, the adoption of modern farming techniques has led to improved yields and resource efficiency.

Emerging Challenges

- Water Scarcity: With increasing water stress, there is a growing emphasis on efficient water management practices, including the expansion of micro-irrigation systems and rainwater harvesting.

- Soil Health: Efforts to combat soil degradation include the promotion of organic fertilizers, crop rotation, and the use of biofertilizers to maintain soil fertility.

- Farmer Distress: Addressing issues like rural poverty, debt, and farmer suicides remains a priority, with new welfare schemes and mental health support programs being introduced.

Research and Development

- Genetically Modified Crops: The introduction of new GM crops, such as pest-resistant cotton and nutrient-enhanced rice, has sparked discussions on their potential benefits and regulatory challenges.

- Biofortification: Research into biofortified crops, like iron-rich pearl millet and zinc-fortified wheat, aims to address malnutrition and improve public health outcomes.

|

175 videos|624 docs|192 tests

|

FAQs on Agriculture-1 - Geography for UPSC CSE

| 1. What are the main causes of low productivity in Indian agriculture? |  |

| 2. How can Indian agriculture be reorganized? |  |

| 3. What are the key principles of organic farming? |  |

| 4. What is shifting cultivation and why is it practiced in some regions of India? |  |

| 5. What is the cropping pattern in Indian agriculture? |  |