Kings, Farmers, and Towns Class 12 History

Introduction

The long span of 1500 years following the end of the Harappan Civilization saw several significant developments in different parts of the Indian subcontinent. These changes were pivotal in shaping the political, economic, and social landscapes of early Indian history.

1. Prinsep and Piyadassi

- In the 1830s, James Prinsep, an officer in the mint of the East India Company, deciphered Brahmi and Kharosthi, two scripts used in the earliest inscriptions and coins.

Lithograph by Prinsep

Lithograph by Prinsep

- Prinsep found that most of these inscriptions mentioned a king referred to as Piyadassi, meaning "pleasant to behold," and some inscriptions also referred to the king as Asoka, a famous ruler known from Buddhist texts.

- This breakthrough gave a new direction to investigations into early Indian political history as European and Indian scholars used inscriptions and texts in various languages to reconstruct the lineages of major dynasties, establishing the broad contours of political history by the early twentieth century.

- Subsequently, scholars shifted focus to the context of political history, investigating connections between political changes and economic and social developments, realizing that these links were complex and not always direct.

What are Inscriptions?

What are Inscriptions?

2. The Earliest States

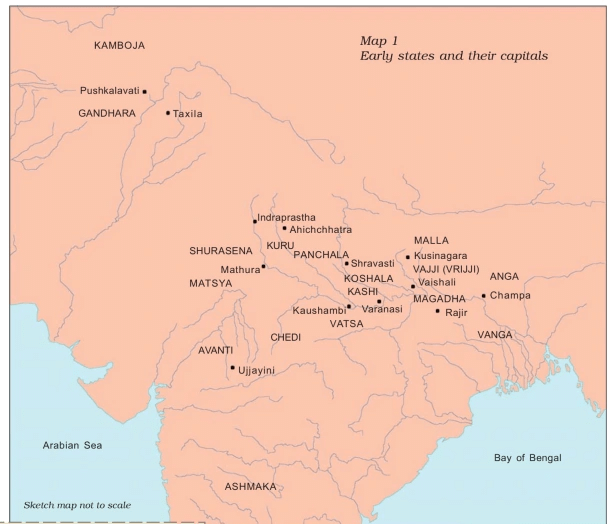

The Sixteen Mahajanapadas

The sixth century BCE is an era associated with early states, cities, the growing use of iron, the development of coinage, etc.

- Early Buddhist and Jaina texts mention, amongst other things, sixteen states known as mahajanapadas. Although the lists vary, some names such as Vajji, Magadha, Koshala, Kuru, Panchala, Gandhara, and Avanti occur frequently. Clearly, these were amongst the most important mahajanapadas.

- While most mahajanapadas were ruled by kings, some, known as ganas or sanghas, were oligarchies where power was shared by a number of men, often collectively called rajas.

- Each mahajanapada had a capital city, which was often fortified.

- From c. sixth century BCE onwards, Brahmanas began composing Sanskrit texts known as the Dharmasutras. These laid down norms for rulers (as well as for other social categories), who were ideally expected to be Kshatriyas.

- Some states acquired standing armies and maintained regular bureaucracies. Others continued to depend on militia, recruited, more often than not, from the peasantry.

First Amongst the Sixteen: Magadha

Between the sixth and the fourth centuries BCE, Magadha (in present-day Bihar) became the most powerful mahajanapada.

- It was a region where agriculture was especially productive. Besides, it was also rich in natural resources and animals like elephant, which was an important part of the army, could be procured from the forest spreads of the region. Ganga and its tributaries provided a means of cheap and convenient communication.

- Magadha attributed its power to the policies of individuals: ruthlessly ambitious kings of whom Bimbisara, Ajatasattu and Mahapadma Nanda are the best known, and their ministers, who helped implement their policies.

- Rajagaha (the Prakrit name for presentday Rajgir in Bihar) was the capital of Magadha initially. In the fourth century BCE, the capital was shifted to Pataliputra, present-day Patna.

3. An Early Empire

The growth of Magadha culminated in the emergence of the Mauryan Empire.

Finding out about the Mauryas

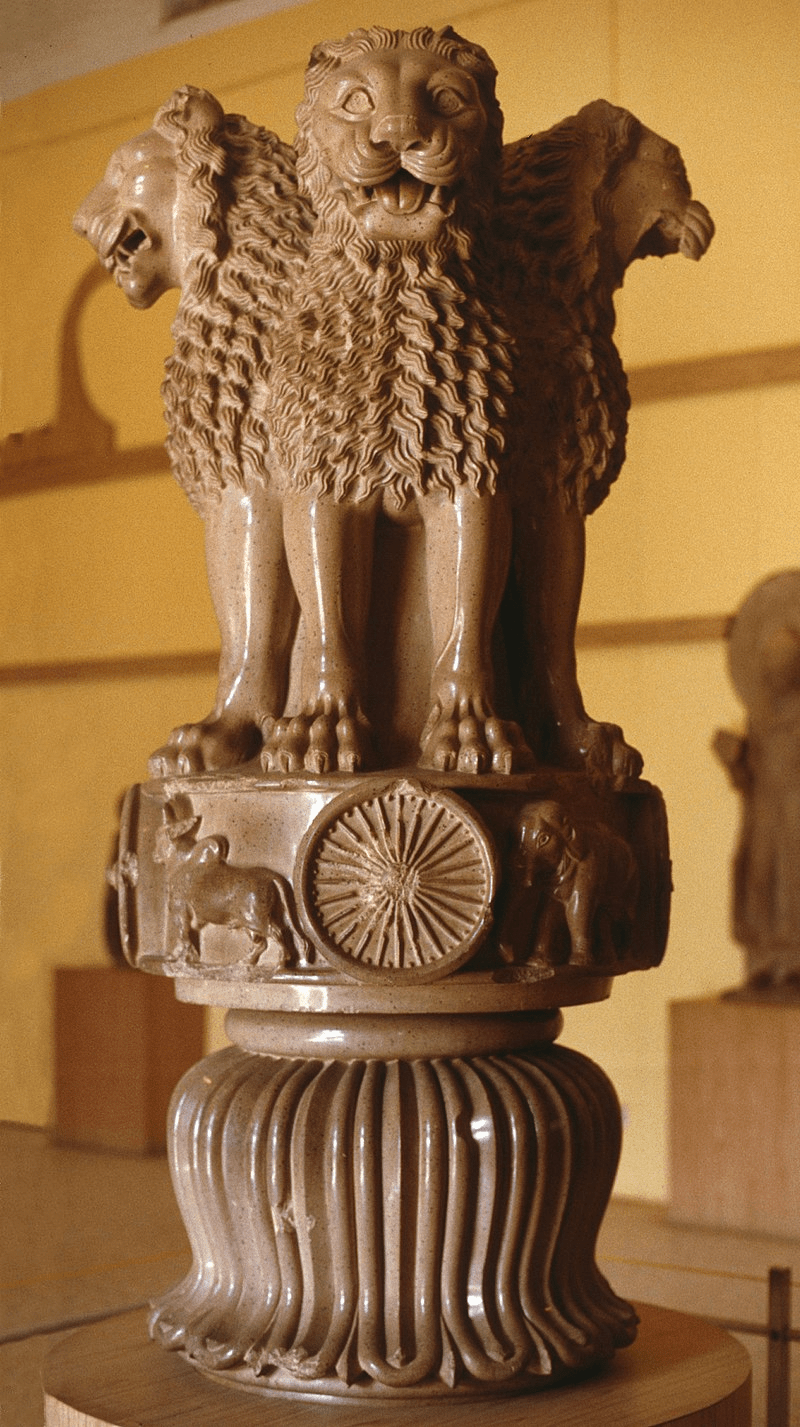

- Historians have used various sources to reconstruct the history of the Mauryan Empire, including archaeological finds, particularly sculpture.

- Contemporary works, such as the account of Megasthenes (a Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya), are valuable despite surviving only in fragments.

- Another key source is the Arthashastra, parts of which were likely composed by Kautilya or Chanakya, traditionally believed to be Chandragupta's minister.

- The Mauryas are also mentioned in later Buddhist, Jaina, and Puranic literature, as well as in Sanskrit literary works.

- Among the most valuable sources are the inscriptions of Asoka (c. 272/268-231 BCE) on rocks and pillars.

- Asoka was the first ruler to inscribe his messages to his subjects and officials on stone surfaces, using these inscriptions to proclaim dhamma.

- Asoka's dhamma included respect towards elders, generosity towards Brahmanas and renouncers of worldly life, kind treatment of slaves and servants, and respect for other religions and traditions.

The Lion Capital

The Lion Capital

Administering the empire

- The empire had five major political centres: the capital Pataliputra and the provincial centres of Taxila, Ujjayini, Tosali, and Suvarnagiri, all mentioned in Asokan inscriptions.

- The inscriptions carried virtually the same message across the empire, from the North West Frontier Provinces of Pakistan to Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and Uttarakhand in India.

- Historians believe a uniform administrative system across such a diverse empire is unlikely, given the contrasting terrains like the hilly regions of Afghanistan and the coast of Orissa.

- Administrative control was likely strongest around the capital and provincial centres, which were strategically chosen. Taxila and Ujjayini were on important long-distance trade routes, while Suvarnagiri was important for its gold mines in Karnataka.

- Effective communication along land and river routes was vital for the empire's existence. Journeys from the centre to provinces could take weeks or months, necessitating provisions and protection.

- The army was crucial for protection, with Megasthenes mentioning a committee with six subcommittees for military coordination: navy, transport and provisions, foot-soldiers, horses, chariots, and elephants. The second subcommittee managed diverse activities like arranging bullock carts, procuring food and fodder, and recruiting support staff.

- Asoka propagated dhamma to unify his empire, appointing special officers known as dhamma mahamatta to spread the message of dhamma, aimed at ensuring the well-being of people in this world and the next.

How important was the empire?

- In the nineteenth century, historians viewed the emergence of the Mauryan Empire as a major landmark while reconstructing early Indian history.

- At the time, India was under colonial rule, part of the British empire, making the idea of an early Indian empire both challenging and exciting for Indian historians.

- Archaeological finds associated with the Mauryas, such as stone sculpture, were considered examples of the spectacular art typical of empires.

- Many historians found the message on Asokan inscriptions unique, portraying Asoka as a powerful yet humble ruler, different from others who adopted grandiose titles.

- Asoka’s portrayal as more powerful and industrious, yet humble, inspired nationalist leaders in the twentieth century.

- The Mauryan Empire lasted about 150 years, which is relatively short in the vast history of the subcontinent.

- The empire did not encompass the entire subcontinent, and control within its frontiers was not uniform.

- By the second century BCE, new chiefdoms and kingdoms emerged in several parts of the subcontinent.

Chiefs and Chiefdoms in 2nd Century BCE India

Chiefs and Chiefdoms in 2nd Century BCE India

4. New Notions of Kingship

Chiefs and kings in the south

- This development was mainly seen in the Deccan and further south, including the chiefdoms of the Cholas, Cheras, and Pandyas in Tamilakam (the name of the ancient Tamil country, which included parts of present-day Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, in addition to Tamil Nadu), proved to be stable and prosperous.

- Many chiefs and kings, including the Satavahanas who ruled over parts of western and central India (c. second-century BCE-second century CE) and the Shakas, a people of Central Asian origin who established kingdoms in the north-western and western parts of the subcontinent, derived revenues from long-distance trade.

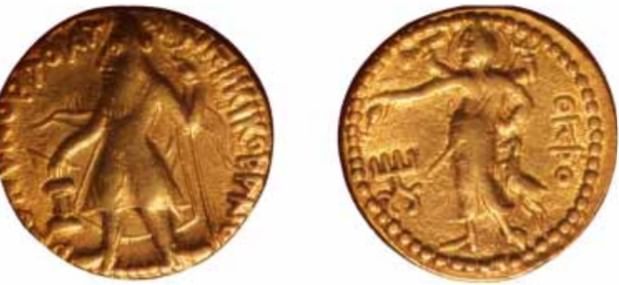

A Kushana Coin

A Kushana Coin

Divine kings

- One means of claiming high status was to identify with a variety of deities. The Kushanas (c. first-century BCEfirst century CE), who ruled over a vast kingdom extending from Central Asia to northwest India followed this strategy. They adopted the title devaputra, or “son of god”, installed colossal statues in shrines.

- By the fourth century, there is evidence of larger states, including the Gupta Empire. These states depended on samantas, men who maintained themselves through local resources including control over land.

- The Prayaga Prashasti (also known as the Allahabad Pillar Inscription) composed in Sanskrit by Harishena, the court poet of Samudragupta, arguably the most powerful of the Gupta rulers (c. fourth century CE).

5. A Changing Countryside

Popular perceptions of kings

- Inscriptions do not provide comprehensive answers about what subjects thought of their rulers, and ordinary people rarely left accounts of their thoughts and experiences.

- Historians have examined stories in anthologies like the Jatakas and the Panchatantra, which likely originated as popular oral tales later written down. The Jatakas were written in Pali around the middle of the first millennium CE.

- One story, the Gandatindu Jataka, describes the plight of subjects under a wicked king, including elderly women and men, cultivators, herders, village boys, and even animals.

- In the story, the king, disguised, learns that his subjects curse him for their miseries, complaining of attacks by robbers at night and tax collectors during the day, leading them to abandon their village for the forest.

- The story reflects the strained relationship between kings and their subjects, especially the rural population, who often found high taxes oppressive.

- Escaping into the forest was an option for those oppressed by high taxes, as shown in the Jataka story. Other strategies aimed at increasing production to meet growing tax demands were also adopted.

Strategies for increasing production

- The shift to plough agriculture spread in fertile alluvial river valleys such as those of the Ganga and the Kaveri from around the sixth century BCE.

- The iron-tipped ploughshare was used to turn the alluvial soil in areas with high rainfall, leading to increased agricultural productivity.

- In parts of the Ganga valley, the introduction of transplantation dramatically increased paddy production, though it required back-breaking work for producers.

- The use of the iron ploughshare was limited to certain regions; cultivators in semi-arid areas like parts of Punjab and Rajasthan did not adopt it until the twentieth century.

- In hilly tracts of the northeastern and central subcontinent, hoe agriculture was practiced, better suited to the terrain.

- Another strategy to increase agricultural production was the use of irrigation through wells, tanks, and less commonly, canals.

- Both communities and individuals organized the construction of irrigation works, with powerful men, including kings, often recording such activities in inscriptions.

Differences in rural society

- Technologies such as the iron-tipped ploughshare and irrigation led to increased agricultural production but the benefits were unevenly distributed.

- Growing differentiation in agricultural society is evident from Buddhist stories and Pali texts that refer to landless laborers, small peasants, and large landholders (gahapati).

- Large landholders and hereditary village headmen became powerful, often controlling other cultivators.

- Early Tamil literature (Sangam texts) identifies categories like large landowners (vellalar), ploughmen (uzhavar), and slaves (adimai), likely based on differential access to land, labor, and new technologies.

- Control over land became crucial, frequently addressed in legal texts.

Pali Texts

Pali Texts

Land grants and new rural elites

- From the early centuries of the Common Era, land grants were recorded in inscriptions, mostly on copper plates and sometimes on stone.

- These grants were often made to religious institutions or Brahmanas and were generally inscribed in Sanskrit, with some later inscriptions including local languages like Tamil or Telugu.

- An inscription from Prabhavati Gupta, daughter of Chandragupta II and wife of a Vakataka ruler, shows she had access to land despite Sanskrit legal texts stating women should not have independent access to resources like land.

- The inscription provides insights into rural populations, including Brahmanas, peasants, and others who were expected to provide produce to the king or his representatives and obey the new lord of the village.

- Land grants varied regionally in size and the rights given to recipients, ranging from small plots to vast stretches of uncultivated land.

- Historians debate the impact of land grants: some see them as a strategy to extend agriculture, while others view them as signs of weakening political power as kings made land grants to win allies and maintain a façade of control.

- These grants offer insights into the relationship between cultivators and the state but exclude groups like pastoralists, fisherfolk, hunter-gatherers, mobile artisans, and shifting cultivators who did not keep detailed records.

6. Towns and Trade

New Cities

- From around the sixth century BCE, urban centers emerged in various parts of the subcontinent.

- Many of these cities were capitals of mahajanapadas.

- Major towns were strategically located along communication routes: Pataliputra on riverine routes, Ujjayini on land routes, and Puhar near the coast.

- Cities like Mathura became bustling centers of commercial, cultural, and political activity.

Urban Populations: Elites and Craftspersons

- Kings and ruling elites resided in fortified cities.

- Extensive excavations are difficult due to modern habitation, but various artifacts have been recovered, including Northern Black Polished Ware, ornaments, tools, weapons, vessels, and figurines made of gold, silver, copper, bronze, ivory, glass, shell, and terracotta.

- By the second century BCE, short votive inscriptions, which were gifts given to religious institutions, in cities mentioned donors and their occupations: washing folk, weavers, scribes, carpenters, potters, goldsmiths, blacksmiths, officials, religious teachers, merchants, and kings.

- Guilds or shrenis of craft producers and merchants regulated production, procured raw materials, and marketed finished products.

- Craftspersons likely used iron tools to meet the growing demands of urban elites.

Trade in the Subcontinent and Beyond

- From the sixth century BCE, extensive land and river routes connected various regions: overland routes extended into Central Asia and beyond, and overseas routes from coastal ports reached East and North Africa, West Asia, Southeast Asia, and China.

- Rulers attempted to control these routes, possibly offering protection for a price.

- Travelers included peddlers traveling on foot, merchants traveling with caravans of bullock carts and pack-animals, and seafarers, whose ventures were risky but profitable.

- Successful merchants (known as masattuvan in Tamil and setthis and satthavahas in Prakrit) could become extremely wealthy.

- A wide range of goods were traded: salt, grain, cloth, metal ores, finished products, stone, timber, medicinal plants, and spices.

- The Roman Empire had a high demand for spices, especially pepper, as well as textiles and medicinal plants

Coins and Kings

- The introduction of coinage facilitated exchanges: punch-marked coins made of silver and copper appeared from the sixth century BCE.

- Numismatists have studied these coins to reconstruct possible commercial networks. Some punch-marked coins were likely issued by kings, while others were issued by merchants, bankers, and townspeople.

- The Indo-Greeks were the first to issue coins bearing the names and images of rulers in the second century BCE.

- The Kushanas issued large hoards of gold coins in the first century CE, identical in weight to those of Roman emperors.

- Yaudheyas of Punjab and Haryana issued several thousand copper coins.

- Gupta rulers issued some of the most spectacular gold coins, facilitating long-distance transactions.

- From the sixth century CE, the frequency of gold coin finds decreased, leading to debates among historians: some suggest an economic crisis due to the decline in long-distance trade after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, while others argue new towns and trade networks emerged, with coins remaining in circulation rather than being hoarded.

The gift of an image

The gift of an image

7. Back to Basics: How Are Inscriptions Deciphered?

Deciphering Brahmi

- Most scripts used to write modern Indian languages are derived from Brahmi, the script used in most Asokan inscriptions.

- From the late eighteenth century, European scholars, aided by Indian pandits, worked backwards from contemporary Bengali and Devanagari manuscripts, comparing their letters with older specimens.

- Scholars initially assumed early inscriptions were in Sanskrit, but they were actually in Prakrit.

- James Prinsep deciphered Asokan Brahmi in 1838 after decades of painstaking investigation by several epigraphists.

How Kharosthi was Read

- The decipherment of Kharosthi, the script used in inscriptions in the northwest, was aided by the finds of coins of Indo-Greek kings who ruled the area (c. second-first centuries BCE).

- These coins had names written in both Greek and Kharosthi scripts.

- European scholars who could read Greek compared the letters, identifying symbols such as "a" in both scripts.

- With Prinsep identifying the language of the Kharosthi inscriptions as Prakrit, it became possible to read longer inscriptions.

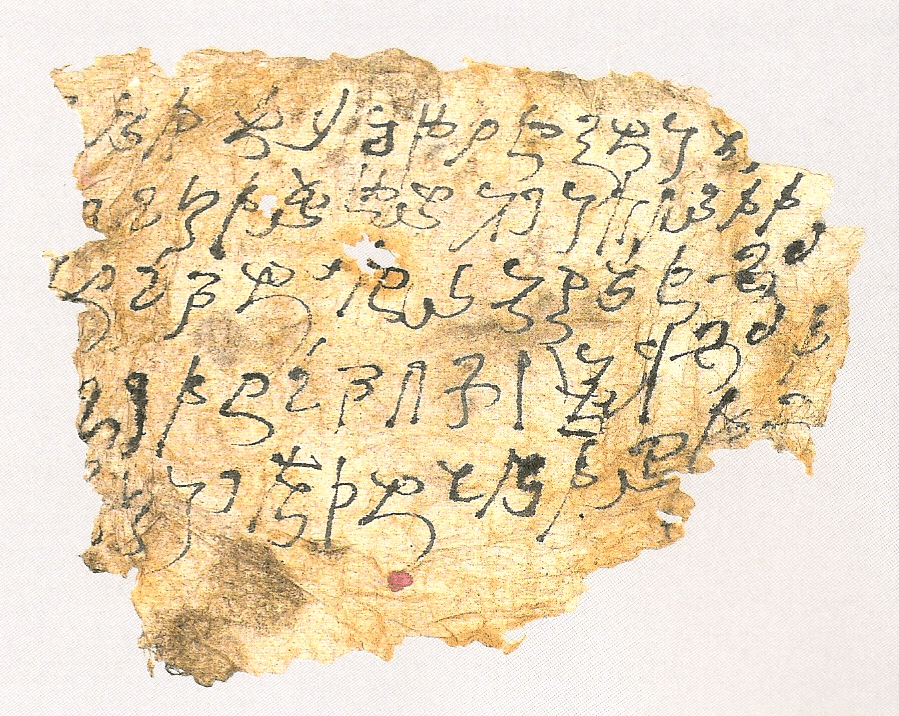

Kharosthi

Kharosthi

Historical Evidence from Inscriptions

- Asokan inscriptions do not mention the name Asoka, but use titles like devanampiya ("beloved of the gods") and piyadassi ("pleasant to behold").

- By examining these titles across inscriptions, epigraphists concluded they were issued by the same ruler.

- Historians must assess the accuracy of statements in inscriptions, such as Asoka's claim that earlier rulers had no arrangements to receive reports.

- Inscriptions are often added to with words in brackets to clarify meanings without altering the intended message.

- Historians also consider whether inscriptions, placed on rocks near cities or important routes, were read by passers-by, given that most people were likely illiterate.

- There are complexities in interpreting inscriptions, such as the one reflecting Asoka's anguish over warfare, which is not found in the region that was conquered, suggesting it may have been too painful to address there.

- The inscription indicates that Asoka claimed earlier rulers had no arrangements to receive reports.

- Historians must constantly assess the statements in inscriptions to judge their truthfulness, plausibility, or exaggeration.

- Epigraphists and historians after examining all these inscriptions, and finding that they match in terms of content, style, language, and paleography, come to a conclusion. .

8. The Limitations of Inscriptional Evidence

- However, it is probably evident that there are limits to what epigraphy can reveal. Sometimes, there are technical limitations, or inscriptions may be damaged or letters missing.

- Besides, it is not always easy to be sure about the exact meaning of the words used in inscriptions.

- Although several thousand inscriptions have been discovered, not all have been deciphered, published, and translated.

- Thus epigraphy alone does not provide a full understanding of political and economic history. Also, historians often question both old and new evidence.

Timeline to Remember

- 600-500 BCE: Emergence of Mahajanapadas

- 500-400 BCE: Rulers of Magadha consolidate power

- 544-492 BCE: Reign of Bimbisara

- 492-460 BCE: Tenure of Ajatsatru

- 269-231 BCE: Reign of Ashoka

- 185 BCE: End of the Mauryan empire

- 201 BCE: Kalinga war was fought

- 335-375 CE: Reign of Sumudragupta

- 375-415 CE: Reign of Chandragupta-II

- 500-600 CE: Rise of the Chalukyas in Karnataka and of the Pallavas in Tamil Nadu

- 606-647 CE: Harshavardhana king of Kanauj; Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang comes in search of Buddhist texts

- 712 CE: Arabs conquer Sind

- 1784 CE: Asiatic Society (Bengal) was founded

- 1810 CE: Colin Mackenzie collects over 8,000 inscriptions in Sanskrit and Dravidian languages.

- 1838 CE: Brahmi script James Prinsept deciphered.

- 1877 CE: Alexander Cunningham published a set of Asokan inscriptions.

- 1886 CE: First issue of Epigraphia Camatica, journal of South Indian inscriptions.

- 1888 CE: First issue of Epigraphia Indica.

- 1965-66 CE: D.C. Sircar published Indian Epigraphy and Indian Epigraphical Glossary.

Key Concepts in Nutshell

Several developments in different parts of the subcontinent (India) the long span of 1500 years following the end of Harappan Civilization:

- Rigveda was composed along the Indus and its tributaries.

- Agricultural Settlements emerged in several parts of the subcontinent.

- A new mode of disposal of the dead emerged like making Megaliths.

- By C 600 BCE growth of new cities and kingdoms were witnessed. It was a major turning point in early Indian history, seeing the growth of 16 Mahajanapadas. Many were ruled by kings. Some known as ganas or sanghas were oligarchies.

- Between 600 BCE and 400 BCE, Magadha became the most powerful Mahajanapada.

- The emergence of Mauryan Empire: Chandragupta Maurya (C 321 BCE) founder of the empire extended control up to Afghanistan and Baluchistan.

- His grandson Ashoka, was the most famous ruler, who conquered Kalinga.

- Variety of sources to reconstruct the history of the Mauryan Empire – archaeological finds especially sculpture, Ashoka’s Inscriptions, Literary sources like Indica account of megasthenes, Arthashastra of Kautilya and Buddhist, Jaina and puranic literature.

- Five major political centers – Pataliputra, Taxila, Ujjayani, Tosali, and Suvarnagiri to administer the empire.

- Ashoka’s Dhamma held his empire together. It included respect towards elders, generosity towards Brahmanas and renouncers of worldly life, kind treatment of slaves and servants, and respect for other religions and traditions.

|

30 videos|225 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Kings, Farmers, and Towns Class 12 History

| 1. What were the key features of the earliest states in ancient history? |  |

| 2. How did the concept of kingship evolve during the formation of early empires? |  |

| 3. What impact did trade and towns have on early societies? |  |

| 4. How are inscriptions deciphered, and what role do they play in understanding ancient history? |  |

| 5. What are the limitations of inscriptional evidence in historical research? |  |

|

Explore Courses for Humanities/Arts exam

|

|