Mannerism and Baroque Art Chapter Notes | AP European History - Grade 9 PDF Download

Introduction

The Renaissance’s legacy endured as its artistic ideals inspired new movements like Mannerism and Baroque, reflecting Europe’s evolving cultural and religious landscape. This chapter notes explores the transition from Renaissance harmony to Mannerist complexity and the ornate grandeur of Baroque art, music, and architecture. It highlights how these styles, shaped by the Counter-Reformation and absolute monarchies, expressed power, faith, and emotion, leaving a lasting impact.

Remains of the Renaissance

- The Renaissance’s influence lingered even as the period drew to a close. Artists like Michelangelo and Donatello profoundly shaped a new generation of creators.

- These post-High Renaissance artists developed a novel artistic style, deeply rooted in Renaissance principles but striving for distinctiveness. This style, known as Mannerism, marked a shift toward a more complex and unique aesthetic.

Mannerism: A Shift Toward Complexity

- Mannerism is an artistic and architectural style that emerged in the late 16th century and persisted until the early 17th century. It is defined by its artificiality, exaggeration, and intricate designs.

- Mannerist art featured elongated, contorted poses, unconventional color schemes,asymmetry, and surprising perspectives, deliberately moving away from the classical Renaissance ideals of balance, harmony, and proportion.

- Emerged in the late 16th century, continuing into the early 17th century.

- A response to the idealized symmetry and beauty of the High Renaissance.

- Prominent in Italy, France, and the Netherlands.

- Key artists: Giorgio Vasari, Tintoretto, Bronzino, and Pontormo.

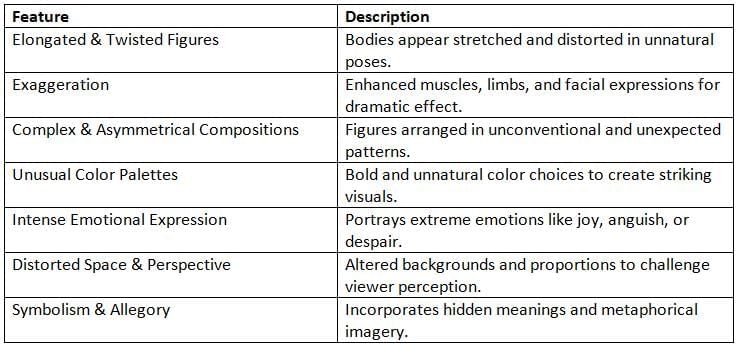

Characteristics of Mannerist Art

In contrast to the orderly compositions of the Renaissance, Mannerist works often evoke a sense of chaos and unease, reflecting the growing uncertainty and tension of the late 16th century, particularly amid Europe’s religious and political conflicts.

The Rise of Baroque: Art in the Age of the Counter-Reformation

- Mannerism gave way to Baroque art with the advent of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Baroque is an artistic and architectural style that arose in the late 16th century and continued until the late 17th century.

- It is characterized by lavish ornamentation, striking contrasts of light and shadow, and a sense of movement and energy. Baroque art features elaborate decorations, vibrant colors, and dynamic compositions, driven by the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation.

- Many Baroque churches and cathedrals were constructed during this period, designed with grand, ornate elements to awe and inspire devotion in viewers.

- Baroque art sought to engage audiences, immersing them in religious narratives through motion, magnificence, and theatricality.

- Originated in Italy and spread to Spain, France, the Low Countries, and Latin America.

- Linked to the Catholic Church and absolute monarchies.

- Used to evoke reverence, faith, and political authority.

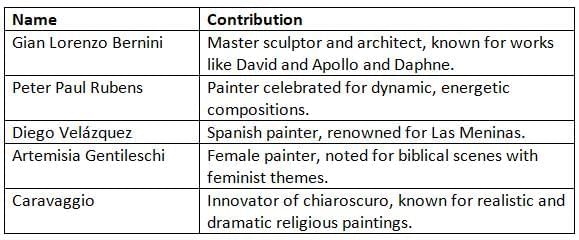

- Key artists: Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, Diego Velázquez, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

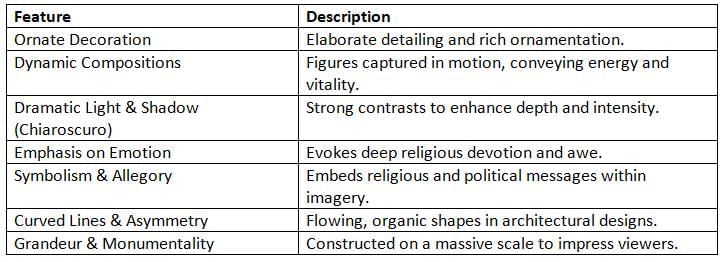

Characteristics of Baroque Art & Architecture

Example: Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s The Ecstasy of St. Teresa—a vividly theatrical sculpture depicting religious ecstasy, with flowing drapery and dramatic lighting effects.

Baroque Music

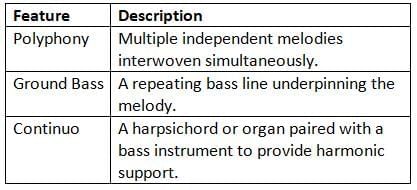

- Baroque music is a genre of Western classical music that emerged in the late 16th century and persisted until the late 17th century. It is defined by its intricate and ornate melodies, complex counterpoint, and lush harmonies. Known for its emotional depth, Baroque music often employed ground bass—a recurring bass line supporting the melody.

- Influenced by the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, much of Baroque music was composed for religious purposes, including Masses, Motets, and Oratorios.

Key Features of Baroque Music

Notable Baroque composers include:

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Renowned for his mastery of counterpoint, exemplified in The Well-Tempered Clavier.

- George Frideric Handel: Famous for composing Messiah and grand oratorios.

- Antonio Vivaldi: Known for The Four Seasons, celebrated for his violin concertos.

- Claudio Monteverdi: A pioneer of opera, recognized for L’Orfeo.

Baroque music served not only religious functions but also allowed royal courts to display their power and refinement.

Baroque Architecture: Power and Prestige

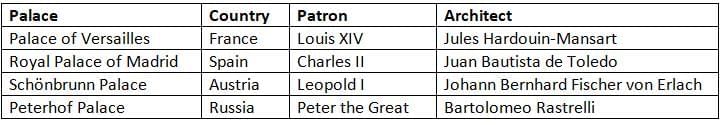

- During the Baroque era, absolute monarchs like Louis XIV of France and Charles II of Spain commissioned lavish architectural projects to showcase their authority and wealth. These opulent structures were not merely residences but political instruments, designed to impress, intimidate, and reinforce royal power.

- In France, Louis XIV, known as the Sun King, oversaw the construction of the Palace of Versailles, a symbol of his dominance and France’s grandeur. Designed by architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the palace served as a governmental hub and an emblem of monarchical power.

Major Baroque Palaces & Their Patrons

Note: The Palace of Versailles, commissioned by Louis XIV, became the quintessential symbol of absolute monarchy, setting a standard for royal courts across Europe.

Key Figures of the Baroque Era

FAQs on Mannerism and Baroque Art Chapter Notes - AP European History - Grade 9

| 1. What are the main characteristics of Mannerism in art? |  |

| 2. How did Baroque art reflect the ideals of the Counter-Reformation? |  |

| 3. Who were some key figures in Baroque art and their contributions? |  |

| 4. What are the distinguishing features of Baroque architecture? |  |

| 5. How did Mannerism serve as a bridge between the Renaissance and Baroque styles? |  |