Romanticism Chapter Notes | AP European History - Grade 9 PDF Download

Introduction

Romanticism, emerging in the late 18th century, was a transformative cultural movement that countered the Enlightenment’s rationalism and the Industrial Revolution’s mechanization. This chapter notes explores Romanticism’s emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality, its impact on art, literature, and spirituality, and its role in fostering nationalism. It examines how Romanticism reshaped European thought amid revolutionary and industrial upheaval.

What Was Romanticism?

- Romanticism was a literary, artistic, and intellectual movement that arose in the late 18th century as a response to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. While the Enlightenment prioritized reason, empirical evidence, and structure, Romanticism championed emotion, imagination, nature, and spiritual depth.

- Romantic thinkers believed that humans were driven not only by logic but also by passion, intuition, and moral sensibilities. This shift helped individuals navigate the emotional turmoil of revolutions and wars, particularly the violence of the French Revolution and the alienation brought by industrialization, which left many feeling mechanical, monotonous, and disconnected.

Romanticism was more than an artistic trend; it was a cultural rebellion against the Enlightenment’s detached rationalism, urban alienation, and the mechanization of nature and society.

Romanticism’s Intellectual Roots

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a key precursor to Romanticism, emphasized the value of natural emotions, moral instincts, and the individual’s relationship with society in his writings.

- In Emile (1762), Rousseau promoted education guided by emotion and personal growth rather than the rigid, rational methods of the Enlightenment.

- In The Social Contract, he introduced the concept of the general will, prioritizing communal values over individual self-interest.

Rousseau’s belief in the inherent goodness of humanity and the corrupting effects of civilization inspired Romanticism’s focus on innocence, nature, and personal emotion.

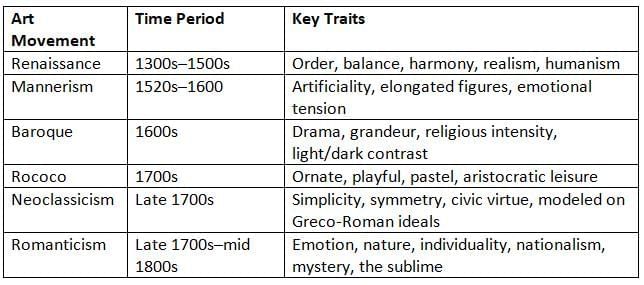

Romanticism vs. Earlier Art Movements

Romanticism diverged from Neoclassicism, which emphasized reason and idealized classical antiquity. Rather than portraying restrained nobility and civic virtue, Romantic artists embraced the intense power of emotion, celebrating national identity, nature’s grandeur, and human imagination.

Romantic Art

Romantic painters employed vivid colors, striking lighting, and untamed landscapes to evoke profound emotional responses. Their works often depicted heroism, rebellion, and suffering, mirroring the revolutionary spirit of the era.

Key Themes

- Nature as majestic and awe-inspiring

- The individual in conflict or reflection

- National myths, folklore, and historical traditions

- Exotic locales, violence, and political fervor

Famous Works

- Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix: A powerful symbol of revolution and nationalism, portraying a female figure, Liberty, guiding French citizens in uprising.

- The Third of May, 1808 by Francisco Goya: A stark depiction of wartime atrocities during Napoleon’s occupation of Spain.

- Imaginary View of the Grand Gallery of the Louvre in Ruins (1796) by Hubert Robert: A romanticized vision of decay and the sublime, housed in the Louvre.

Romantic Literature

Romantic writers focused on emotion, inner conflict, dreams, and defiance of societal conventions. They often glorified rural life, childhood, the past, and the natural world, rejecting the lifeless conformity of urban and industrial society.

Key Characteristics

- Prioritizing the individual over society

- Valuing emotion over reason

- Exalting nature over civilization

- Portraying common people as noble and heroic

- Fascination with the supernatural, exotic, and tragic

Major Authors

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther: A tragic tale of unrequited love that triggered “Werther Fever” across Europe, establishing Werther as the archetype of the emotional, misunderstood Romantic hero.

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: A cautionary story about unchecked scientific ambition, blending Gothic horror with Romantic themes of nature, emotion, and isolation.

- Jane Austen: While more grounded and nuanced, her novels explore personal emotions and social identity, securing her place within the Romantic literary tradition.

Romantic Religion and Spirituality

The rise of Romanticism coincided with religious revival movements, notably Methodism, which emphasized personal faith, heartfelt devotion, and emotional worship over rigid dogma.

John Wesley and Methodism

- Opposed the Enlightenment’s strict rationalism and secularism.

- Emphasized emotional conversion experiences, outreach to the masses, and support for the poor.

- Fostered a sense of moral community and spiritual nationalism, particularly in Britain.

Romantic spirituality often embraced mysticism, the sacredness of nature, and intuitive religious experiences, prioritizing these over formal religious institutions or theology.

Romanticism and Nationalism

- Romanticism played a significant role in promoting nationalism across 19th-century Europe.

- Romantic thinkers and artists celebrated each nation’s unique spirit—its language, folklore, customs, and history—asserting that a nation’s identity should be rooted in the shared emotional and cultural heritage of its people.

Key Examples

- Germany: Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the Brothers Grimm advanced German national identity through language and folklore.

- Italy: Romantic operas and literature fueled aspirations for national unification.

- Eastern Europe: Nationalist movements used Romantic poetry and legends to revive suppressed cultural identities under imperial rule.

Romanticism inspired not only emotional revolutions of the heart but also political revolutions for national identity, laying the groundwork for the unifications of Germany and Italy in the later 19th century.

Why Romanticism Matters

- Romanticism was more than a stylistic movement; it was a profound cultural transformation that reshaped how Europeans perceived the self, society, and the world.

- It reflected disillusionment with Enlightenment rationalism and the turmoil of revolution and war, while establishing the emotional and ideological foundations for modern nationalism, individualism, and social activism.

Key Terms

- Allegory: A narrative method where characters and events symbolize broader themes, often conveying moral, political, or spiritual messages, reflecting Romanticism’s exploration of emotional and philosophical depths through metaphorical storytelling.

- Charlotte: A French dessert of fruit purée or custard in a mold lined with ladyfingers or sponge cake, embodying Romanticism’s emphasis on beauty, craftsmanship, and sensory pleasure in culinary art.

- Common Language and Subjects: Unifying linguistic and thematic elements in Romantic art, literature, and philosophy, fostering national identity and cultural unity through shared emotions and regional experiences.

- Dramatic: The expression of intense emotions and significant events to captivate audiences, highlighting Romanticism’s focus on individual experience, nature’s beauty, and emotional depth in contrast to rationalism.

- Egypt: A symbol of exoticism and inspiration in the Romantic period, with its ancient monuments and cultural richness influencing themes of nature, history, and human experience in art and literature.

- Enlightenment: A late 17th–18th century movement emphasizing reason, individualism, and skepticism of tradition, shaping political and social changes that Romanticism reacted against.

- French Flag: Known as Le Tricolore, with blue, white, and red stripes, symbolizing liberty, equality, and fraternity, central to the French Revolution and 19th-century nationalism.

- German Countryside: Rural German landscapes idealized in the Romantic period as symbols of authentic, simple life, contrasting with industrialization and urban alienation.

- Idealization of Family (Women and Children) and Rural Life: A Romanticized view celebrating familial bonds, women as nurturing figures, children as innocent, and rural life as pure, countering industrial and urban influences.

- Imaginary View of the Grand Gallery of the Louvre in Ruins, Hubert Robert (1796): A Romantic painting depicting the Louvre in decay, evoking nostalgia and the sublime, highlighting transience and nature’s reclamation of human structures.

- Industrialization: The transformation from agrarian to industrial economies, marked by mass production and factories, altering social and cultural norms, which Romanticism critiqued.

- Jane Austen: An English novelist whose works, blending realism and Romantic emotional depth, explore love, marriage, and social identity, contributing to the Romantic literary tradition.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: A German writer whose works, emphasizing emotion, nature, and individuality, significantly shaped European Romanticism.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: An 18th-century philosopher whose ideas on natural goodness, emotion, and the social contract influenced Romanticism’s focus on nature and individual feeling.

- Liberty Leading the People, Eugène Delacroix (1830): A Romantic painting symbolizing the July Revolution, with Liberty as a vibrant figure leading revolutionaries, embodying freedom and national pride.

- Middle East: A region of cultural and historical significance, inspiring Romantic artists with its exoticism and themes of history and human experience.

- Narrator/Writer’s Emotions and Inner Thoughts: The personal feelings and mental states expressed in Romantic texts, evoking empathy and providing insight into human experience.

- Nature, Beauty, Personal Expression, Imagination: Core Romantic concepts celebrating nature as inspirational, beauty as essential, personal expression as inner truth, and imagination as a transcendent force.

- Picturesque: An aesthetic valuing beauty and charm in scenes that evoke emotion and imagination, central to Romantic depictions of nature.

- Rationalism and Industrialization: Rationalism’s emphasis on reason fueled industrial advancements, which Romanticism opposed, favoring emotional and natural values.

- Revolution: A rapid, often violent change in political or social structures, influencing Romantic themes of rebellion and emotional upheaval.

- Romanticism: A late 18th–early 19th century movement emphasizing emotion, individualism, and nature, reacting against Enlightenment rationalism and industrialization.

- Romantic Literature: Literature of the late 18th–early 19th centuries focusing on emotion, individualism, nature, and the sublime, opposing rationalism and industrial conformity.

- Romantic Art: Art from the late 18th–early 19th centuries emphasizing emotion, individualism, and nature’s sublime beauty, contrasting with Neoclassical order.

- Scientific Revolution: A 16th–18th century shift to empirical evidence and scientific methods, influencing Enlightenment rationalism that Romanticism countered.

- Struggles Against Societal Norms: Romantic resistance to conventional expectations, emphasizing individual expression and emotional depth over societal conformity.

- Symbolism: A late 19th-century movement using symbols to convey deeper meanings, reflecting Romanticism’s focus on individualism and inner exploration.

- The Shadows of French Heroes who died in the wars of Liberty, received by Ossian, Anne-Louis Girodet (1802): A Romantic painting glorifying heroism and sacrifice, evoking national identity and nostalgia.

- The Sorrows of Young Werther: Goethe’s 1774 novel of unrequited love, embodying Romantic themes of intense emotion and individualism, sparking widespread influence.

- Unconventional Heroes and Heroines: Romantic characters defying traditional heroism, showcasing complex, flawed personalities and emotional depth.

- Unrequited Love: One-sided romantic attraction, a prevalent Romantic theme highlighting profound emotional suffering and longing.

- Urbanization: The growth of urban populations driven by industrialization, critiqued by Romanticism for its alienation and loss of natural connection.

- War: Violent conflict between organized groups, shaping Romantic themes of heroism, suffering, and emotional intensity.

- Werther: The protagonist of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, embodying Romantic emotional depth and the struggle against societal norms.

FAQs on Romanticism Chapter Notes - AP European History - Grade 9

| 1. What were the main characteristics of Romanticism? |  |

| 2. How did Romanticism differ from earlier art movements? |  |

| 3. In what ways did Romanticism influence nationalism? |  |

| 4. What role did nature play in Romantic literature? |  |

| 5. Why is Romanticism considered important in the context of modern art and literature? |  |