Unit 1: Theory of Production Chapter Notes | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Overview |

|

| Meaning of Production |

|

| Factors of Production |

|

| Problems Faced by Enterprises |

|

| Law of Variable Proportions or the Law of Diminishing Returns |

|

| Production Optimization |

|

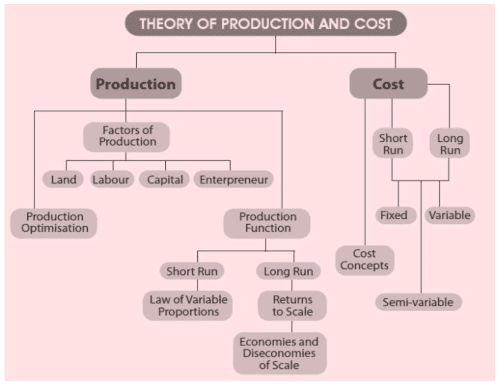

Overview

Meaning of Production

- Production is a vital economic activity that underpins the foundation of any successful economy. The ability of a firm to produce goods and services at a competitive cost is essential for its survival in a competitive market. Business managers primarily focus on achieving optimal efficiency in production by minimizing production costs.

- The performance of an economy is assessed by its level of production, which determines its wealth or poverty. The standard of living for people in a country depends on the volume and variety of goods and services produced. While high production levels contribute to a country's wealth, factors such as resource distribution, economic policies, and social conditions also play significant roles.

- In everyday language, 'production' refers to activities that create tangible goods, such as farming and manufacturing. However, in Economics, production is used in a broader sense to denote the process of utilizing resources like labor, materials, capital, and time to transform them into commodities and services to meet human needs.

- Production encompasses any economic activity that converts inputs into outputs capable of satisfying human wants. This includes the creation of material goods and the provision of services, as long as they fulfill the needs of individuals. For instance, the making of cloth by an industrial worker, the delivery of goods by a retailer, and the services of professionals like doctors and teachers are all considered production in Economics.

Production, as defined by James Bates and J.R. Parkinson, is the systematic process of transforming resources into finished goods and services to meet demand. It's essential to understand that production doesn't involve creating matter from scratch, but rather adding utility to existing materials. For instance, when a carpenter makes a table, he is not creating the wood but transforming it into a useful product.

Production encompasses various processes that enhance the utility of natural resources, including:

- Changing the form of natural resources to create physical products with greater utility, such as turning a log into a table or iron into machinery.

- Changing the place of resources to increase their utility, such as extracting minerals from the earth or transporting goods to areas where they are in higher demand.

- Changing the time of resource availability, such as storing harvested grains for future use or canning seasonal fruits for off-season consumption.

- Utilizing personal skills and services, such as those of organizers, merchants, and transport workers, to enhance production and distribution.

Production refers to the process of creating goods and services to satisfy human wants. The core idea behind production is to create utility, which means making something useful or valuable in some way. This can involve changing the form of a product, adding value by transporting it, or making it available at the right time. For instance, when producing a woollen suit, the process involves several steps:

- Form Utility: Wool is transformed into woollen cloth through spinning and weaving.

- Place Utility: The finished cloth is transported to a place where it can be sold.

- Time Utility: Woollen clothes are produced in advance and kept until they are needed by consumers.

Throughout this process, various people, such as mill workers and shopkeepers, provide services that contribute to the creation of utility. Production can also involve intangible inputs and outputs, as seen in services provided by lawyers, doctors, and consultants. However, activities done out of love, voluntary services, and goods made for personal use without the intention to sell do not count as production. The production process is all about creating different types of utility, whether it’s changing the form, adding value through location, or making something available at the right time.

The costs incurred during production, known as the cost of production, are crucial for business decision-making, even if they are not the focus of pure production analysis. Factors such as cost and revenue will be discussed in later units.

Factors of Production

Factors of production are the essential inputs required to produce goods and services. They include:

- Land: Refers to all natural resources used in production, such as water, minerals, and forests.

- Labour: Involves the human effort, both physical and mental, used in the production process.

- Capital: Includes man-made resources used in production, such as machinery, tools, and buildings.

- Entrepreneurship: Refers to the ability to combine the other factors of production and take risks to create a business.

These factors are crucial for the production of even the simplest goods, like a loaf of bread. While land is a natural gift, the other factors require human effort and creativity. In a modern economy, the production process is complex, involving multiple stages and various inputs, depending on the nature of the output. For example, producing a smartphone requires not just the physical materials but also advanced technology, skilled labour, and effective management.

1. Land

- Characteristics of Land- Gift of Nature: Land is a natural resource that does not require human effort to create. It is provided by nature without any cost, as there is no payment made to obtain it.

- Fixed Supply: The supply of land is limited and cannot be increased. While the total supply of land is fixed, its price and utilization can be influenced by demand. Therefore, from an economic perspective, land supply is perfectly inelastic, but from a firm’s viewpoint, it is relatively elastic.

- Permanent and Indestructible: Land is permanent and cannot be destroyed. According to economist David Ricardo, land possesses original and indestructible qualities that cannot be eliminated.

- Passive Factor: Land is a passive factor of production. It does not produce anything on its own without human intervention. Human effort is required to make land productive.

- Immobility: Land is immobile in a geographical sense. It cannot be physically moved from one location to another, and the natural characteristics specific to a particular piece of land cannot be transferred to other areas.

- Multiple Uses: Land can be used for various purposes, but its suitability for different uses varies. Some land may be more suitable for agriculture, while others may be better for industrial or commercial activities.

- Heterogeneity: No two pieces of land are identical. They differ in terms of fertility, location, and other natural attributes, which affect their productivity and use.

2. Labour

Definition of Labour:

- Labour refers to any mental or physical effort aimed at producing goods or services for an economic reward.

- It encompasses various human efforts involving physical exertion, skill, and intellect, although the proportion of each may vary.

- For instance, a farmer ploughing his field is engaged in labour because he is using his physical strength and knowledge to produce food.

Economic Significance:

- Labour gains economic significance when it is performed with the intention of earning an income.

- Activities done out of love or affection, such as a parent caring for a child, do not constitute labour in the economic sense.

- For example, a teacher tutoring a student for free is not engaging in labour, whereas a teacher charging a fee for the same service is.

Characteristics of Labour:

- Human Effort: Labour is unique because it is directly connected to human efforts. Unlike other factors of production, labour involves psychological and human considerations. Therefore, aspects like leisure, fair treatment, and a positive work environment are crucial for labourers.

- Perishability: Labour is highly perishable. A day's labour lost cannot be compensated by extra work on another day. For instance, if a construction worker misses a day's work, they cannot make up for it by working extra hours in the future.

- Active Factor: Labour is an active factor of production. Without the active participation of labour, land and capital cannot produce anything. For example, machinery (capital) and land cannot generate crops without the labour of farmers.

- Inseparability: Labour is inseparable from the labourer. A labourer is the source of their own labour power. When a labourer sells their services, they must be physically present to deliver them. For instance, a chef cannot sell their services without being present in the kitchen.

- Heterogeneity: Labour is heterogeneous, meaning labour power differs from person to person. Factors such as inherent abilities, acquired skills, work environment, and motivation affect labour efficiency. For example, two workers may have different levels of productivity based on their skills and the working conditions.

Features of Labour Supply

1. All Labour May Not Be Productive:

- Not all efforts put into work guarantee the creation of resources.

2. Weak Bargaining Power of Labour:

- Labour does not have a reserve price, meaning they cannot store their ability to work for later.

- This lack of storage capability forces labourers to accept the wages offered by employers.

- As a result, labourers have weaker bargaining power compared to employers and can be exploited, leading to lower wages.

- Historically, labourers have been economically weaker than employers, although there have been improvements for labourers in the 20th and 21st centuries.

3. Mobility of Labour:

- In theory, workers can move from one job to another or from one location to another easily.

- However, in practice, there are various obstacles that hinder the free movement of labour between different jobs and locations.

4. Supply of Labour Over Time:

- While the total supply of labour cannot change abruptly due to economic conditions, it can evolve over time as market dynamics change.

5. Choice Between Labour and Leisure:

- Labourers have the option to choose between working hours and leisure hours.

- This choice creates a unique backward-bending shape in the supply curve of labour.

- Generally, when wage rates increase, labourers tend to supply more labour by reducing their leisure time.

- However, beyond a certain income level, labourers may prefer to decrease their supply of labour and increase their leisure time, even if wage rates continue to rise.

- This means they prioritize rest and leisure over earning additional money.

Capital

- Capital refers to the part of a person's or community's wealth that is used to create more wealth. It's important to understand that capital is different from wealth. While wealth includes all useful goods and human qualities that can be passed on for value, only a portion of these can be considered capital. When resources are idle, they represent wealth, not capital.

- Capital is often called ‘ produced means of production ’ or ‘ man-made instruments of production .’ This means capital includes all human-made goods used to produce more wealth. This sets capital apart from land and labor, which are not produced factors. Land and labor are original factors of production, while capital is created by humans working with nature. Examples of capital include machine tools, factories, dams, canals, and transport equipment, all of which are made by humans to assist in producing more goods.

Types of Capital

- Fixed Capital: This type of capital is durable and provides services over time. Examples include tools and machines.

- Circulating Capital: This capital is used in production in a single instance and cannot be reused. Examples include seeds, fuel, and raw materials.

- Real Capital: This refers to physical assets such as buildings, plants, and machinery.

- Human Capital: This pertains to human skills and abilities, which require significant investment to develop.

- Tangible Capital: This type of capital can be perceived by the senses, such as physical goods. In contrast, intangible capital includes rights and benefits that are not physically perceivable, such as copyrights, goodwill, and patent rights.

- Individual Capital: This refers to personal property owned by individuals or groups.

- Social Capital: This includes assets owned by society as a whole, such as roads and bridges.

Capital Formation

Capital formation, also known as investment, is essential not only for replacing and renovating existing assets but also for creating additional productive capacity. This process requires sacrificing some current consumption and channeling savings into productive investments. The willingness of society to abstain from present consumption directly impacts the level of savings and investment dedicated to new capital formation.If a society consumes all it produces without saving, its future productive capacity will decline as current capital equipment wears out. To avoid this, it is crucial to redirect some current resources towards creating capital goods like tools, machines, and transport facilities. A higher rate of capital formation leads to increased production efficiency, economic growth, and more employment opportunities.

Stages of Capital Formation

1. Savings

- Dependence on Income: Capital formation hinges on the ability to save, which is directly influenced by an individual’s income. Generally, higher incomes lead to higher savings because as income increases, the propensity to consume decreases and the propensity to save increases. This principle applies not only to individuals but also to entire economies. Wealthier countries with higher income levels can save more and, consequently, become richer more quickly compared to poorer countries.

- Willingness to Save: Beyond the ability to save, the willingness to save is equally important. This willingness is influenced by an individual’s foresight regarding their future and the social environment in which they live. Individuals who are more concerned about securing their future are likely to save more. Additionally, governments can encourage savings by implementing policies such as compulsory savings for employees through insurance and provident funds or offering tax deductions on saved income.

- Importance of Business and Government Savings: In recent times, the savings of the business community and government have also become significant factors in capital formation. Businesses that save and reinvest profits contribute to capital formation, and governments that save can direct funds towards investment in public goods and infrastructure.

Overall, both the ability and willingness to save are crucial for capital formation, and various factors including income levels, government policies, and social attitudes towards saving play a vital role in determining these aspects.

2. Mobilization of Savings:

- It's not enough for people to just save money; those savings need to be put into circulation to facilitate capital formation .

- The availability of suitable financial products and institutions is crucial for mobilizing savings.

- There should be a widespread network of banks and financial institutions to collect public savings and direct them to potential investors.

- The state plays a vital role in this process by generating savings through fiscal and monetary incentives and channeling those savings towards the community's priority needs. This ensures both capital generation and socially beneficial capital formation.

3. Investment

- Capital formation is only complete when real savings are transformed into tangible capital assets.

- An economy needs an entrepreneurial class willing to take business risks and invest savings in productive ventures to create new capital assets.

Entrepreneur

Who is an Entrepreneur?

- Entrepreneur is the factor of production which mobilises, organises and manages other factors of production. Entrepreneur is also known as Organiser, Manager, Risk Taker, Innovator etc.

- Entrepreneur is the one who takes the initiative to set up a business to produce goods and services.

Functions of an Entrepreneur

(i) Risk Bearing

- Entrepreneurs earn profits by bearing the uncertainty that comes with changes in a dynamic economy.

- While other functions of an entrepreneur can be delegated to paid managers, risk bearing is a unique responsibility that cannot be passed on.

- This makes risk bearing the most crucial function of an entrepreneur.

(ii) Innovations

- Schumpeter believes that the core role of an entrepreneur is to introduce innovations .

- Innovations involve applying new ideas or inventions commercially to meet business needs more effectively.

- This can include developing new or improved products, processes, technologies, or business models, and entering untapped markets.

- Entrepreneurs drive economic growth and technological progress by continuously introducing innovations.

- While successful innovations can lead to significant profits, they are often quickly imitated, leading to a decrease in unique profit margins.

- The ability to innovate varies among individuals, and those with higher innovative capabilities contribute to a greater supply of entrepreneurs, further accelerating technological advancement.

Enterprise’s Objectives and Constraints

- Traditionally, it is assumed that the primary goal of an enterprise is to maximize profits.

- However, in reality, enterprises consider various factors and do not base their decisions solely on profit maximization.

- Enterprises operate within an economic, social, political, and cultural context, and their objectives must align with their survival and growth in these environments.

Therefore, the objectives of an enterprise can be categorized into:

- Organic Objectives: Focused on the internal growth and development of the enterprise.

- Economic Objectives: Related to financial performance and economic impact.

- Social Objectives: Aimed at contributing positively to society.

- Human Objectives: Concentrated on the well-being and development of human resources.

- National Objectives

1. Organic Objectives

- Survival: The fundamental goal for all enterprises is to survive. To survive, an enterprise must produce and distribute goods or services at a price that covers its costs. If it fails to do so, it cannot meet its obligations to creditors, suppliers, and employees, leading to bankruptcy. Therefore, survival is crucial for the continuation of business activities.

- Growth and Expansion: Once an enterprise ensures its survival, it can focus on growth and expansion. Growth has become a significant objective, especially with the rise of professional managers.

- Balanced Growth Rate: R.L. Marris’s theory suggests that managers aim to maximize the firm’s balanced growth rate, considering managerial and financial constraints. While owners seek to maximize profit, capital, market share, and public reputation, managers focus on salary, power, status, and job security. Despite potential conflicts, both objectives align towards steady growth.

- Rate of Growth: Managers optimize the balanced rate of growth, involving the increase in demand for the firm’s products and the supply of capital.

2. Economic Objectives

- Profit Maximization: For over two hundred years, economists have assumed that firms aim to maximize profits. This assumption is straightforward, rational, and quantitative, suitable for equilibrium analysis. Firms determine their price and output policies to maximize profits within constraints like technology and finance.

- Investor Expectations: Investors expect companies to earn sufficient profits to provide fair dividends and improve stock prices. Creditors and employees are also interested in profitable enterprises, as creditors are hesitant to lend to unprofitable businesses.

Profits and their Definition:

- Profits are the funds remaining with the firm after all costs have been deducted from the revenue. The company can use these funds for reinvestment or any other purpose. The profit earned by the firm is the reward to the entrepreneur for his efforts and risk. The profit earned by the firm is also the source of funds for paying the salary of employees, manager and other factors of production.

Accounting Profit vs Economic Profit:

- Profit, in the accounting sense, is the difference between total revenue and total costs of the firm. Economic profit is the difference between total revenue and total costs, but total costs here include both explicit and implicit costs.

- Accounting profit considers only explicit costs while economic profit reflects explicit and implicit costs, including the opportunity costs of the entrepreneur's time and resources used in their own business.

- Since economic profit includes these opportunity costs associated with self-owned factors, it is generally lower than accounting profit.

Normal Profits vs Supernormal Profits:

- Normal profits include the normal rate of return on capital invested by the entrepreneur, remuneration for the labour, and the reward for the risk-bearing function of the entrepreneur.

- Normal profit (zero economic profit) is a component of costs and represents the minimum that a business owner needs to continue operating.

- Supernormal profit, also called economic profit or abnormal profit, is over and above normal profits.

- It is earned when total revenue is greater than total costs. Total costs in this case include a reward to all the factors, including normal profit.

Criticism of Profit Maximization Objective:

- The profit maximization objective has been criticized by many economists in recent years.

- Some economists argue that not all firms aim to maximize profits.

- H. A. Simon suggests that firms have a “satisfying” behavior and strive for satisfactory profits rather than maximum profits.

- Baumol’s theory of sales maximization posits that sales revenue maximization, rather than profit maximization, is the ultimate goal of business firms.

- He provides empirical evidence to support his hypothesis that sales are prioritized over profits as the main objective of the enterprise.

Managerial Theories of Firm Behaviour:

- In 1932, A. A. Berle and G.C. Means observed that in large business corporations, there is a separation between management and ownership. This separation gives managers the discretion to set goals for the firms they oversee. Williamson’s model on maximizing managerial utility is a significant contribution to the managerial theory of firm behavior.

- In joint-stock companies, owners (shareholders) typically prefer profit maximization. However, managers tend to maximize their own utility, ensuring a minimum profit, rather than solely focusing on profit maximization.

Utility Maximization in Different Firm Types:

- Entrepreneur-Owned Firms: In firms owned and managed by the entrepreneur, utility maximization means considering both the money profits and the leisure time sacrificed when deciding on the level of output.

- Large Joint-Stock Companies: In larger companies, managers’ utility functions include not just profits for shareholders but also factors like sales promotion, maintaining upscale offices, and overseeing a larger staff. Managers aim to find the best balance between profits and these additional objectives.

Cyert and March’s Functional Goals:

Cyert and March propose four functional goals that can complement the profit objective in firms: production goal, inventory goal, sales goal, and market share goal.

3. Social Objectives

- Supply of Goods: Businesses should ensure a continuous supply of unadulterated goods and articles of standard quality.

- Ethical Practices: Enterprises must avoid profiteering and anti-social practices.

- Employment Opportunities: Creating opportunities for gainful employment for the local population is essential.

- Pollution Prevention: Businesses should ensure their output does not cause any form of pollution, be it air, water, or noise.

- Community Contribution: Enterprises need to contribute positively to the quality of life in their community and society at large. Failure to do so may jeopardize their survival.

4. Human Objectives

- Importance of Human Resources: Human beings are the most valuable resource of an organization. Their comprehensive development should be a major objective.

- Employee Development: Focus on the overall development of employees, including their skills, knowledge, and well-being.

- Employee Engagement: Foster a conducive work environment that engages employees and makes them feel valued.

- Work-Life Balance: Ensure that employees have a healthy work-life balance to enhance their productivity and satisfaction.

- Recognition and Rewards: Implement systems for recognizing and rewarding employee contributions to motivate them further.

5. National Objectives

National objectives refer to the goals and targets set by a nation to achieve overall development and progress in various sectors, such as economy, education, health, infrastructure, and social welfare. These objectives are aimed at improving the quality of life of citizens, promoting sustainable development, and reducing inequalities within the country. National objectives guide the formulation of policies and programs at the national and state levels to ensure focused and coordinated efforts towards achieving the desired outcomes.

Remove inequality of opportunities: Provide fair opportunities for all to work and progress.

Produce according to national priorities: Align production with the country’s priorities.

Self-reliance: Reduce dependence on other nations and promote self-sufficiency.

Skill formation: Train young men as apprentices to contribute to skill development for economic growth.

Conflict of Objectives: An organization may have multiple goals and objectives that may conflict with each other. For example, the goal of maximizing profits may conflict with the goal of increasing market share, which may require lowering prices or improving quality. Similarly, the goal of social responsibility may conflict with the goal of introducing new technology that may lead to job losses or environmental harm. In such cases, managers need to find a balance between conflicting objectives to achieve reasonable success in both areas.

Profit Maximization: While discussing the objectives of an enterprise, it is assumed that firms aim at maximizing profits unless stated otherwise. Profit maximization is a common objective for firms under various market conditions, such as perfect competition, monopoly, etc. However, it is important to note that no comprehensive economic theory explaining the behavior of firms under different market conditions has been developed so far.

Constraints on Profit Maximization: When pursuing the objective of profit maximization, enterprises may face several constraints that hinder their ability to achieve this goal. Some of the important constraints include:

Lack of Knowledge and Information: Enterprises operate in an uncertain environment where accurate information about various factors affecting performance is often unavailable. This includes information about input prices, technological characteristics, and market conditions. The lack of such information makes it difficult to determine the profit-maximizing price and strategy.

Public Interest Restrictions: Governments may impose restrictions in the public interest on production, pricing, and the movement of factors such as labor and capital. These restrictions can limit the flexibility of enterprises to operate freely and maximize profits.

Infrastructural Inadequacies: Insufficient infrastructure and supply chain bottlenecks can lead to shortages and emergencies that disrupt operations. Issues such as frequent power cuts, irregular raw material supply, and inadequate transportation facilities can hinder profit maximization efforts.

Economic and Business Condition Changes: Fluctuations in demand, changes in government policies, and external factors such as natural disasters can impact sales and revenues. Sudden changes in fiscal, regulatory, or contractual requirements can also impose constraints on firms, affecting their profitability and growth plans.

Cost Increases: Factors such as inflation, rising interest rates, and unfavorable exchange rate fluctuations can increase the costs of raw materials, capital, and labor. These cost increases can disrupt budgets and financial plans, making it challenging to achieve profit maximization.

Skilled Workforce Availability: The inability to find skilled workers at competitive wages and the need for ongoing personnel training can impose significant constraints on firms. A shortage of skilled labor can impact productivity and operational efficiency, further limiting profit maximization potential.

Problems Faced by Enterprises

Enterprises encounter various challenges from their inception to closure. Here are some insights into these problems:

1. Problems Related to Objectives: Enterprises operate within an economic, social, political, and cultural environment, and their objectives must align with this environment. However, these objectives are often diverse and conflicting. For example, the goal of maximizing profits may clash with the objective of increasing market share, which typically involves improving quality and lowering prices. Therefore, enterprises face the challenge of not only selecting their objectives but also finding a balance among them.

2. Problems Related to Location and Size of the Plant

- Location: An enterprise must decide whether to locate its plant near the source of raw materials or close to the market. This decision involves considering various costs, including labor, facilities, and transportation. The entrepreneur needs to weigh these factors to choose the most economical location.

- Size of the Firm: The enterprise must determine whether to operate on a small scale or a large scale. This decision requires careful consideration of technical, managerial, marketing, and financial aspects. The management should realistically assess its strengths and limitations when deciding on the size of the new unit.

3. Problems Related to Selecting and Organizing Physical Facilities

- Production Process and Equipment: A firm needs to decide on the production process and the type of equipment to be used. This choice depends on the design selected and the required volume of production. Large-scale production typically involves complex machinery and specialized processes.

- Evaluation of Equipment and Processes: Entrepreneurs often face multiple options for equipment and production processes. The decision should be based on the relative cost and efficiency of each option.

- Layout Planning: Once the equipment and processes are determined, the entrepreneur prepares a layout plan. This plan outlines the arrangement of equipment, buildings, and the allocation of space for each activity.

4. Problems Related to Finance

- Financial Planning: Involves determining the amount of funds required based on physical plans, assessing product demand and costs, estimating profits on investment, and comparing potential profits with existing concerns.

- Capital Structure: Involves deciding the appropriate mix of debt and equity financing and the timing of financing.

5. Problems Related to Organizational Structure

- Division of Labor: The enterprise needs to divide the total work into specialized functions.

- Department Formation: Proper departments should be constituted for each specialized function to ensure efficient operation.

6. Problems Relating to Organization and Management

(i) Problems relating to organization:

(a) Division of Work: A business organization consists of various functions such as production, finance, marketing, sales, etc. These functions are further divided into several sub-functions, which are performed by different individuals or groups of individuals. Therefore, the first step in the organization of a business is to divide the total work into various parts and assign them to different individuals or groups. This will help in avoiding duplication of work and ensure that each function is performed efficiently.

(b) Departmentalization: After dividing the work, the next step is to group similar activities together and create departments. For example, all activities related to production can be grouped together to form the production department, and all activities related to marketing can be grouped together to form the marketing department. This will help in better coordination and control of activities.

(c) Authority and Responsibility: Every individual or group assigned with a particular task should be given the authority to make decisions related to that task. At the same time, they should also be made responsible for the results of their work. This will ensure that there is no confusion regarding who is responsible for what and will help in faster decision-making.

(d) Span of Control: The span of control refers to the number of subordinates that a manager can effectively supervise. It is important to determine the span of control for each manager in the organization to ensure that they are not overloaded with work and can supervise their subordinates effectively.

(e) Inter-relationship: The inter-relationship between different functions and levels of the organization should be clearly defined. This will help in ensuring that there is no overlap of work and that each function is working towards the same goal.

(f) Coordination: Coordination is the process of ensuring that all activities of the organization are aligned towards the same goal. It is important to establish a system of coordination to ensure that there is no duplication of work and that all functions are working together effectively.

(g) Control: Control is the process of monitoring and evaluating the performance of different functions and individuals in the organization. It is important to establish a system of control to ensure that the organization is on track to achieve its goals and to identify any deviations from the plan.

(h) Flexibility: The organization should be flexible enough to adapt to changes in the environment. This may include changes in technology, customer preferences, or government regulations. A flexible organization will be able to respond quickly to changes and maintain its competitive advantage.

(i) Innovation: The organization should promote a culture of innovation to encourage individuals to come up with new ideas and improve existing processes. This will help in maintaining the competitiveness of the organization and ensuring its long-term success.

(j) Technology: The organization should leverage technology to automate repetitive tasks and improve efficiency. This may include the use of software for project management, communication, and data analysis.

(k) Performance Management: A system of performance management should be established to evaluate the performance of individuals and teams. This may include setting performance targets, providing feedback, and conducting performance reviews.

(l) Training and Development: The organization should invest in the training and development of its employees to enhance their skills and knowledge. This will help in improving the overall performance of the organization and ensuring its long-term success.

(m) Employee Engagement: The organization should focus on engaging its employees by providing them with a conducive work environment, opportunities for growth, and recognition for their contributions. Engaged employees are more likely to be productive and contribute to the success of the organization.

7. Problems relating to marketing:

(a) Market Research: Conducting thorough market research to identify the target market, understand customer needs and preferences, and analyze competitors. This will help in making informed decisions regarding the marketing strategy.

(b) Product Development: Developing products that meet the needs and preferences of the target market. This includes deciding on product features, quality, design, and packaging.

(c) Pricing Strategy: Setting a pricing strategy that is competitive yet profitable. This includes deciding on pricing policies, discounts, and credit terms.

(d) Promotion Strategy: Developing a promotion strategy that effectively communicates the product benefits to the target market. This includes deciding on advertising methods, personal selling techniques, and public relations strategies.

(e) Distribution Strategy: Developing a distribution strategy that ensures the product is available to the target market. This includes deciding on distribution channels, sales outlets, and logistics.

(f) Monitoring and Evaluation: Continuously monitoring and evaluating the marketing strategy to identify any issues and make necessary adjustments. This includes analyzing sales data, customer feedback, and market trends.

8. Problems relating to legal formalities:

(a) Registration: Registering the enterprise with the relevant authorities to obtain the necessary licenses and permits. This includes registering the business name, obtaining a tax identification number, and applying for any industry-specific licenses.

(b) Compliance: Ensuring compliance with all legal requirements related to taxes, labor laws, environmental regulations, and industry-specific regulations. This includes maintaining proper records, filing tax returns, and submitting necessary reports to the authorities.

(c) Legal Structure: Deciding on the legal structure of the enterprise, such as sole proprietorship, partnership, or limited liability company. This will determine the legal obligations and liabilities of the business.

(d) Contracts: Drafting and reviewing contracts with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders to ensure legal protection and avoid disputes. This includes employment contracts, supplier agreements, and customer contracts.

(e) Intellectual Property: Protecting intellectual property rights by registering trademarks, patents, and copyrights as necessary. This will =

help in safeguarding the unique aspects of the business and preventing infringement by others.

(f) Dispute Resolution: Establishing a dispute resolution mechanism to address any legal disputes that may arise during the course of the business. This includes mediation, arbitration, or litigation as appropriate.

9. Problems relating to industrial relations:

(a) Winning Workers’ Cooperation: Management needs to implement strategies to gain the trust and cooperation of workers. This can be achieved through transparent communication, involving workers in decision-making processes, and addressing their concerns promptly.

(b) Maintaining Discipline: A disciplined work environment is crucial for productivity. Management should establish clear rules and regulations, ensure fair enforcement, and provide necessary training to employees to maintain discipline.

(c) Dealing with Organised Labour: Managing relationships with trade unions and organized labor groups can be challenging. Management should engage in constructive dialogue with these groups, negotiate agreements amicably, and address their grievances to avoid conflicts.

(d) Establishing Workplace Democracy: Involving workers in the management process can foster a sense of ownership and responsibility. Management should create platforms for workers to contribute ideas, participate in decision-making, and provide feedback on various aspects of the industry.

(e) Conflict Resolution: Conflicts between management and workers can arise due to various reasons. Management should establish effective conflict resolution mechanisms, such as mediation or negotiation, to address issues before they escalate further.

(f) Employee Engagement: Keeping employees engaged and motivated is essential for a harmonious industrial relation. Management should implement employee engagement initiatives, recognition programs, and career development opportunities to keep employees satisfied and committed.

(g) Adapting to Changes: Industrial relations can be affected by changes in laws, regulations, and economic conditions. Management should stay updated on such changes and adapt their policies and practices accordingly to ensure compliance and maintain positive relations.

Production Function

Production function is a concept in economics that shows the relationship between the inputs used in production and the output produced . It helps to understand how different quantities of inputs can affect the amount of goods or services produced.Key Points:

- The production function is based on the available technology and technical knowledge at a given time.

- It can be seen as the minimum inputs required to produce a specific level of output.

- Inputs include land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial ability .

- For example, a company making beverages needs factories, raw materials, and workers to produce its products.

Simplified Equation:

The production function can be simplified to focus on Labor (L) and Capital (K) as the main inputs. The equation is:

Q = f(L, K)

- Q = Output

- L = Labor

- K = Capital

Short-Run vs Long-Run Production Function

The production function of a firm can be analyzed in the context of the short run or long run. It is important to understand that in economic analysis, the distinction between short run and long run is not based on a specific measurement of time (such as days, months, or years). Instead, it refers to the extent to which a firm can vary the inputs used in the production process.Short-Run Production Function:

- A period is considered the short run if at least one of the inputs used in production remains unchanged. In the short run, the production function shows the maximum amount of a good or service that can be produced with a set of inputs, assuming that at least one input is fixed.

- Typically, during the short run, a firm does not change its capital stock to increase production. This means that capital is treated as a fixed factor in the short run. Therefore, the production function in the short run is studied by keeping the quantity of capital constant while varying other factors such as labor and raw materials. This approach is used when applying the law of variable proportions.

Long-Run Production Function:

- The production function can also be examined in the long run, which is a period of time when all factors of production are variable. In the long run, a firm can install new machines and capital equipment, in addition to increasing variable factors of production.

- A long-run production function illustrates the maximum quantity of a good or service that can be produced with a set of inputs, assuming that the firm can vary the amount of all inputs used. The study of production when all factors of production are allowed to vary is related to the law of returns to scale.

Cobb-Douglas Production Function

The Cobb-Douglas production function is a well-known statistical model used to analyze production processes. It was developed by Paul H. Douglas and C.W. Cobb in the United States, focusing on the production function of American manufacturing industries. Originally, this production function was applied to the entire manufacturing sector in the U.S. rather than individual firms. In this context, output refers to manufacturing production, while the inputs are labor and capital.The Cobb-Douglas production function is mathematically represented as:

Q = KLa C (1-a)

- Q represents output, L denotes the quantity of labor, and C signifies the quantity of capital.

- K and a are positive constants.

From the statistical study conducted by Cobb and Douglas, it was concluded that labor accounted for approximately 3/4th and capital for about 1/4th of the increase in manufacturing production.

Despite its limitations, the Cobb-Douglas production function is widely used in economics as a useful approximation due to its simplicity and the insights it provides into the contributions of labor and capital to production

Law of Variable Proportions or the Law of Diminishing Returns

The law of variable proportions, also known as the law of diminishing returns, examines the relationship between inputs and outputs when one input is variable (like labor) and others are fixed.- Initially, increasing the variable input (labor) can lead to a proportionate increase in output.

- However, as more of the variable input is added, while keeping other inputs constant, the additional output produced from each extra unit of the variable input will start to decrease.

- This means that there is a point beyond which adding more of the variable input will result in smaller and smaller increases in total output.

- For example, if a farmer keeps adding workers to a fixed piece of land, there will be a point where each additional worker contributes less to the overall harvest than the previous one.

Key Concepts:

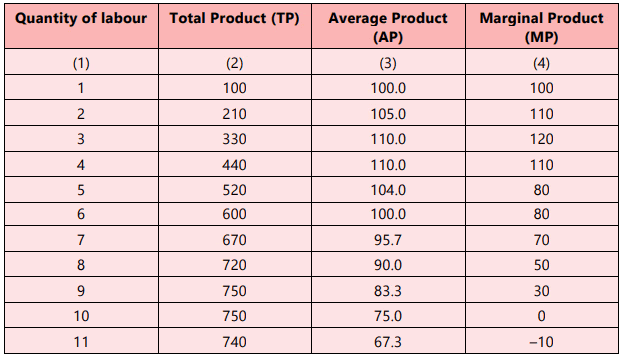

- Total Product (TP): The overall output produced by all factors of production working together. When only one factor is varied (like labor), TP changes with the amount of the variable factor used.

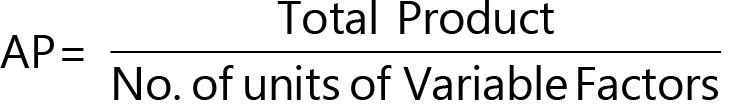

- Average Product (AP): The output per unit of the variable factor, calculated as total product divided by the number of units of the variable factor used.

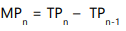

- Marginal Product (MP):The additional output generated by adding one more unit of the variable factor, holding all other factors constant.

Relationship between Average Product and Marginal Product

- When the average product increases due to more input, the marginal product is higher than the average product.

- When the average product is at its highest point, the marginal product equals the average product. This is where the marginal product curve intersects the average product curve at its peak.

- When the average product decreases, the marginal product is lower than the average product.

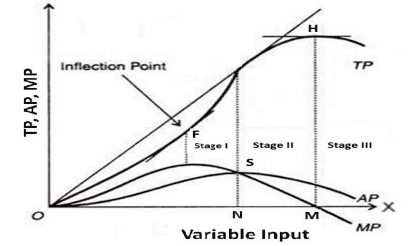

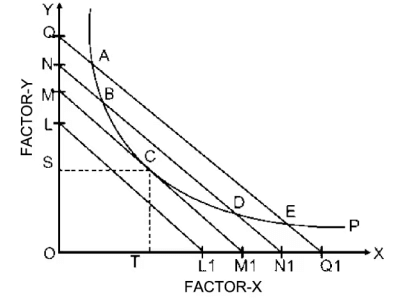

Stages in Law of Variable Proportions

Stage 1: The Stage of Increasing Returns

1. Initial Phase: In the initial phase of Stage 1, the total product (TP) increases at an increasing rate . The marginal product (MP) also rises and reaches its maximum at the point of inflexion. The average product (AP) continues to rise during this period.

2. Diminishing Rate: After reaching a certain point (point F in the figure), the TP continues to rise but at a diminishing rate .

3. AP Peak: Stage 1 ends when the AP curve reaches its highest point. During this stage, the AP curve consistently rises, while the MP curve initially rises and then starts to decline after reaching its maximum.

4. MP Decline: Although the MP starts to decline, it remains greater than the AP throughout this stage, allowing the AP to continue rising.

Explanation of Increasing Returns:

1. Efficient Utilization: The law of increasing returns operates because, initially, the quantity of fixed factors is sufficient to allow for the effective utilization of the variable factor.

2. Improved Efficiency: As more units of the variable factor are added to a constant quantity of fixed factors, the fixed factors are utilized more intensively and effectively. This improvement in efficiency leads to a rapid increase in production.

3. Example: For instance, if a machine operates efficiently with four workers but initially has only three, adding a fourth worker will enhance production because the machine will be utilized to its optimum capacity. This occurs because, initially, some fixed factor capacity was underutilized, and increasing the variable factor allows for fuller utilization of the fixed factor, resulting in increasing returns.

4. Fixed Factor Utilization: The fixed factors remain constant, but their utilization improves with the addition of variable factors, leading to higher production levels.

Stage 2: Stage of Diminishing Returns

- Transition to Stage 2: As we move into Stage 2, the total product continues to increase but at a diminishing rate until it reaches its maximum at point H, marking the end of this stage. During this stage, both the marginal product and average product of the variable factor are positive but decreasing.

- Diminishing Returns: Stage 2 is characterized by diminishing returns because both the average and marginal products of the variable factors are continuously falling during this stage. This stage is crucial as the firm will aim to produce within its range.

Explanation of Diminishing Returns

- Efficiency and Fixed Factors: Diminishing returns occur after a certain point of adding the variable factor to the fixed factor because of the efficient use of fixed factors. Initially, as more units of the variable factor are added, the fixed factor is utilized more efficiently, leading to increasing returns.

- Inadequacy of Fixed Factor: Once the variable factor reaches a level where it can efficiently utilize the fixed factor, any further increase in the variable factor will cause a decline in marginal and average product. This is because the fixed factor becomes inadequate relative to the quantity of the variable factor.

- Example: For instance, if four workers are optimal for one machine, adding a fifth worker will not contribute anything, leading to a decline in marginal productivity.

Stage 3: Stage of Negative Returns

- In Stage 3, the total product declines, the marginal product becomes negative, and the average product continues to diminish. This stage is characterized by the negative marginal product of the variable factor.

- The law of negative returns explains that as the variable factor is increased beyond a certain point, it becomes too excessive relative to the fixed factor. This leads to interference between the factors and a decrease in total output. Reducing the units of the variable factor in this stage can increase total output.

Stage of Operation

- A rational producer typically avoids Stage 3 due to the negative marginal product but may find themselves operating there under specific circumstances. Even in this stage, a producer can increase output by reducing the amount of the variable factor.

- A rational producer also avoids Stage 1 because it does not make the best use of fixed factors and misses opportunities to increase production by adding more variable factors, whose average product continues to rise in this stage.

A rational producer will avoid production in stage 1 and stage 3, as these stages are considered economically absurd or nonsensical. Instead, a rational producer will operate in stage 2, where both the marginal product and average product of variable factors are diminishing.The decision of when to produce in stage 2 depends on factor prices. The optimal level of employing the variable factor, in this case, labor, is determined by the principle of marginalism. This principle suggests that the marginal revenue product of labor should equal the marginal wages under specific market conditions, such as perfect competition. The concept of marginalism is explained in detail in the chapter on equilibrium in different market types.

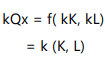

Returns to Scale

The concept of returns to scale examines how output changes when all factors of production are increased or decreased simultaneously and in the same proportion. This is different from changing factor proportions, which involves varying the ratio of different factors while keeping their total constant. Returns to scale can be constant, increasing, or decreasing, depending on how output responds to proportional changes in all inputs.

Constant Returns to Scale:

- When all factors of production are increased by the same proportion and output also increases by the same proportion, it is known as constant returns to scale.

- This can be mathematically represented as:

where k is the proportion by which all factors are increased, Qx is the output, K is the capital, and L is the labor.

where k is the proportion by which all factors are increased, Qx is the output, K is the capital, and L is the labor.

Increasing Returns to Scale: This occurs when output increases by a greater proportion than the increase in inputs. Initially, when a firm expands, it experiences increasing returns to scale. For instance, a 3-foot cube box contains 9 times more wood than a 1-foot cube box, but the capacity of the 3-foot cube box is 27 times that of the 1-foot cube box. Increasing returns to scale can also result from the indivisibility of factors, where certain inputs are available in large and lumpy units and can be utilized more efficiently at a larger scale. Additionally, enhanced specialization in land and machinery can contribute to increasing returns to scale.

Decreasing Returns to Scale: Decreasing returns to scale occur when output increases by a smaller proportion relative to the increase in all inputs. As a firm continues to expand by increasing all inputs, it eventually experiences decreasing returns to scale. This phenomenon arises due to increasing difficulties in management, coordination, and control. When a firm reaches a very large size, maintaining the same level of efficiency in management becomes challenging, leading to decreasing returns to scale.

Cobb-Douglas Production Function: The Cobb-Douglas production function is used to illustrate returns to scale in production. Initially, Cobb and Douglas assumed constant returns to scale, with the exponents summing to 1 in their production function. However, they later relaxed this requirement, allowing for the possibility of increasing or decreasing returns to scale. The revised Cobb-Douglas equation is as follows: Q = K La Cb In this equation, ‘Q’ represents output, ‘L’ denotes the quantity of labor, and ‘C’ stands for the quantity of capital. The constants ‘K,’ ‘a,’ and ‘b’ are positive values.

- Increasing Returns to Scale: If a + b > 1, it indicates increasing returns to scale, where the increase in output is more significant than the proportionate increase in labor and capital inputs.

- Constant Returns to Scale: If a + b = 1, it signifies constant returns to scale, meaning that output increases in the same proportion as the increase in labor and capital factors.

- Decreasing Returns to Scale: If a + b < 1, it indicates decreasing returns to scale, where the increase in output is less than the proportionate increase in labor and capital inputs.

Production Optimization

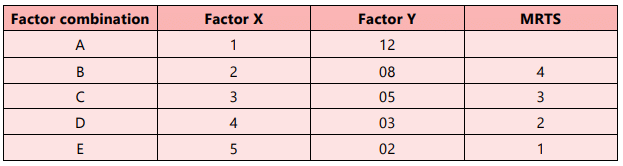

In order to maximize profits, a firm aims to find the combination of production factors (or inputs) that minimizes production costs for a specific output level. This can be achieved by integrating the firm’s production and cost functions, which are represented by isoquants and iso-cost lines, respectively.Isoquants

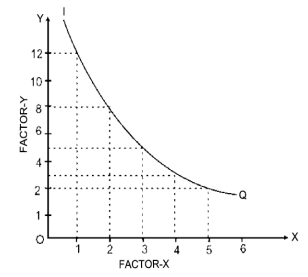

Isoquants are analogous to indifference curves in consumer behavior theory. They depict all possible combinations of inputs that can produce the same level of output. Since an isoquant curve represents various input combinations yielding identical output, the producer has no preference for one over the other. Hence, isoquants are also referred to as equal-product curves, production indifference curves, or iso-product curves.

Isoquants share similar characteristics with indifference curves. They are negatively sloped, convex to the origin due to the diminishing marginal rate of technical substitution (MRTS), and do not intersect. However, a key distinction is that while indifference curves cannot quantify the level of satisfaction a consumer derives, isoquants represent quantifiable production levels. For instance, isoquant IQ1 may represent 100 units of output, with curves like IQ2 and IQ3 indicating higher production levels.

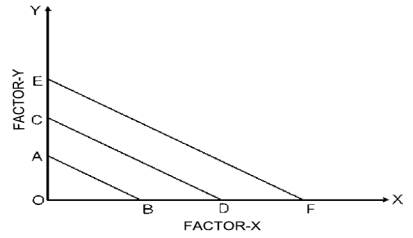

Isocost or Equal-cost Lines

An isocost line, also known as the budget line or budget constraint line, illustrates the various alternative combinations of two factors that a firm can purchase within a given budget. For example, if a firm has ₹ 1,000 to spend on factors X and Y, with prices of ₹ 10 for factor X and ₹ 20 for factor Y, the firm can allocate its budget in different ways. It could spend the entire amount on X, purchasing 100 units of X and no units of Y, or spend entirely on Y, buying 50 units of Y with no units of X. Any combination of X and Y would result in the same total cost, regardless of the specific mix chosen.

Iso-cost Line Iso-cost lines can also be represented diagrammatically. In such a representation, the X-axis denotes the units of factor X, while the Y-axis indicates the units of factor Y. When the entire budget of ₹ 1,000 is allocated to factor X, we obtain point B on the X-axis. Conversely, if the entire amount is spent on factor Y, we reach point A on the Y-axis. The straight line joining points A and B, referred to as the iso-cost line, illustrates all the possible combinations of factors X and Y that the firm can purchase with a fixed outlay of ₹ 1,000.

Isoquants represent the technical conditions for producing a specific level of output, while iso-cost lines depict the various combinations of factors that can be acquired for a fixed total cost, given the prices of the two factors. By analyzing the intersection of isoquants and iso-cost lines, a firm can determine the optimal factor combination for production.

|

86 videos|255 docs|58 tests

|

FAQs on Unit 1: Theory of Production Chapter Notes - Business Economics for CA Foundation

| 1. What is the definition of production in economics? |  |

| 2. What are the main factors of production? |  |

| 3. What is the difference between short-run and long-run production functions? |  |

| 4. What is the Cobb-Douglas production function and its significance? |  |

| 5. What are the key objectives of an enterprise? |  |