Word Choice and Usage Chapter Notes | Language Arts for Grade 12 PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Addressing “Awkward,” “Vague,” and “Unclear” Word Choices |

|

| Writing for an Academic Audience |

|

| Selecting and Using Key Terms |

|

| Strategies for successful word choice |

|

Introduction

Writing involves making a series of decisions. When drafting a paper, you select your topic, approach, sources, and thesis. As you write, you must decide on the words to express your ideas and how to structure them into sentences and paragraphs. During revision, you make further choices, questioning whether your words truly reflect your intent, if readers will grasp your meaning, or if your phrasing is effective. Choosing words that accurately capture your ideas and communicate them clearly to your audience can be challenging. When instructors mark your draft with comments like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy,” they are signaling a need to improve your word choice. This guide will address common word choice issues and provide strategies to select the most effective words during revision.

Keep in mind that revising for clarity may sometimes require crafting a new sentence rather than tweaking an existing one. Don’t cling too tightly to your original wording; starting fresh can often lead to clearer expression.

For advice on broader revisions, refer to our guides on restructuring drafts and revising drafts.

Addressing “Awkward,” “Vague,” and “Unclear” Word Choices

When your paper returns with “awkward” written in the margins, you may wonder why instructors frequently use this term. Such feedback typically highlights sentences that were difficult to understand, urging you to revise them for greater clarity.

Word choice isn’t the sole cause of unclear or awkward sentences. Sometimes, issues arise from grammatical errors or syntax (the arrangement of words and phrases).

For Example, consider: “Having completed studying, the pizza was quickly consumed.” The words here—studying, pizza, consumed—are clear, but the sentence suggests the pizza was studying, which is confusing.

A clearer revision would be: “Having completed studying, the students quickly consumed the pizza.” If a sentence is marked as “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” step into the reader’s perspective to identify where it might mislead or lack key details.

At times, clarity issues stem directly from word choice. Here are some common problems to watch for:

- Misused words: When a word doesn’t mean what the writer intended.

- Example: The Cree people had a uniform culture until French and British settlers arrived.

- Revision: The Cree people had a similar culture.

- Words with unintended connotations or meanings.

- Example: I sprayed the ants in their secret spots.

- Revision: I sprayed the ants in their concealed spots.

- Ambiguous pronouns: When it’s unclear whom or what a pronoun refers to.

- Example: My cousin Jake embraced my brother Trey, even though he wasn’t fond of him.

- Revision: My cousin Jake embraced my brother Trey, even though Jake wasn’t fond of Trey.

- Jargon or technical termsthat overburden readers. Use specialized terms only when necessary for your field, not to appear scholarly.

- Example: The dialectical interplay between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics provides a framework for deontological reasoning.

- Revision: The exchange between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers serves as a model for deontological reasoning.

- Loaded language: Using a term repeatedly without defining it for readers, assuming they understand your intent.

- Example: Society tells young girls that beauty is their greatest asset. To prevent eating disorders and other health issues, we must change society.

- Revision: Modern American media, such as magazines and films, tell young girls that beauty is their greatest asset. To prevent eating disorders and other health issues, we must change the images and role models presented to girls.

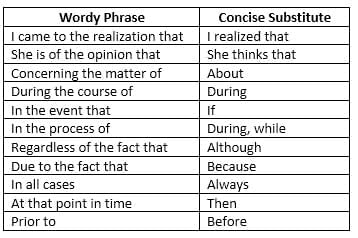

Wordiness

Occasionally, the issue isn’t finding the precise word to convey an idea, but rather using too many words, which readers might see as unnecessary or inefficient. Below is a list of examples.

The left column shows phrases with three, four, or more words that can be streamlined; the right column offers concise alternatives:

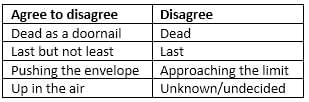

Clichés

- In academic writing, it’s wise to minimize the use of clichés. These are overused phrases that have become stale, predictable, or even irritating due to their frequent use. Clichés weaken writing because their familiarity reduces their impact and they often use multiple words when one would suffice.

- To steer clear of clichés, start by identifying them, then replace them with concise, original alternatives. Consider whether a single word captures the cliché’s meaning. If not, can you express the idea in your own way with two or three words? Below are five common clichés, each paired with alternative expressions. As a challenge, try generating additional alternatives for the last two examples.

Writing for an Academic Audience

- When selecting words to convey your ideas, consider not only what feels and sounds right to you but also what will resonate clearly with your readers. Reflecting on your audience’s expectations will guide your word choice decisions.

- Some writers assume academic audiences expect complex Sajid: I could not generate a response to this message because it contained a quote that exceeded our fair use policy. Please provide a shorter quote or a summary in your own words. complex or technical language to “sound smart.” However, the primary aim of academic writing is to communicate arguments or information clearly and persuasively, not to showcase intelligence. Academic writing has its own distinct style, and as a student, you’re learning to adopt this style. You may use words and grammatical structures unfamiliar from high school writing, but deliberately choosing overly complex or unfamiliar terms can lead to unclear sentences that confuse readers.

- When writing for professors, prioritize simplicity. Simple words do not equate to simple ideas. In academic argument papers, the sophistication lies in the connections you make, presented in clear, straightforward language.

- However, clarity doesn’t mean informality. Most professors will not appreciate a paper written in a casual tone, like a text message or email to a friend. Avoid slang and colloquialisms.

- For example, consider this thesis statement: “Moulin Rouge was awful because the singing was bad and the costume colors were garish, KWIM?” A professor would likely find this inappropriate for an academic paper.

Selecting and Using Key Terms

In academic writing, identifying and incorporating key terms into your paper, including your thesis, is often beneficial. This section explores the difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and provides an example of using key terms effectively in a thesis statement.Repetition vs. Redundancy

- Repetition and redundancy are distinct concepts. Repetition can be valuable, especially when using key terms multiple times, such as in topic sentences, to reinforce important points and maintain cohesion. Sometimes, no synonym can replace a key term without weakening the argument, and repeating it is a deliberate choice to support clarity.

- Redundancy, however, occurs when you repeatedly use the same words—nouns, verbs, or adjectives—or restate the same point unnecessarily, often due to a lack of clear argument or fatigue. This aimless repetition muddles your writing. See the “Strategies” section below for tips on revising redundant text.

Building Clear Thesis Statements

- Clear sentences are crucial throughout your writing, but the thesis statement—one of the most critical sentences in an academic argument paper—deserves special attention. These ideas can also apply to other sentences in your work.

- Crafting a strong thesis statement involves finding words that concisely capture the essence and significance of your essay’s argument. Condensing several paragraphs or pages into a single sentence with precise key terms is challenging but gives writers and readers a clear roadmap of the essay’s direction and purpose. Professors particularly value well-defined thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements, see our dedicated handout.)

- Example: You’re tasked with writing an essay contrasting the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

- After several days, you develop three versions of your thesis:

- Version 1: Many significant river and shore scenes appear in Huckleberry Finn.

- Version 2: The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn highlight a return to nature.

- Version 3: Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that true American democratic ideals are found by leaving civilized society and returning to nature.

- Analyzing word choice in these statements:

- Version 1, “significant” is vague and overused, offering little insight into the argument’s framework.

- Version 2 improves by introducing “return to nature,” providing a clearer direction, but it lacks the argument’s full scope.

- Version 3 is the strongest, presenting a sophisticated argument with clear key terms:

- The contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

- A key term alone is merely a topic, not the argument itself. The argument emerges through how you combine these terms to convey your point clearly.

Strategies for successful word choice

- Use unfamiliar words cautiously. Check their dictionary definitions and context to ensure accuracy.

- Be wary of the thesaurus. Synonyms may carry different connotations or nuances. Use a dictionary to confirm a synonym’s suitability.

- Avoid trying to sound overly authoritative.

- For example, which sentence is clearer?

a) Under current societal conditions, marriage practices exhibit significant uniformity.

b) In our society, people tend to marry those similar to themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- For example, which sentence is clearer?

- Prioritize strong nouns and verbs.Before refining adjectives, ensure your nouns and verbs are precise and robust.

- For example, revise “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War” to “The novel describes a soldier’s experiences during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” specifies the book type, and “describes” clarifies the action.

- Use the slash/option technique. When stuck, list multiple word or phrase options (e.g., “unclear/ambiguous/vague”) and choose or combine the best fit.

- Identify repetition. Determine if it’s purposeful (reinforcing key terms) or redundant (lazy repetition).

- Write your thesis five ways. Create five versions of your thesis to explore different word choices and phrasings. Combine elements from each or select the strongest version to refine your argument. This exercise reveals your range of choices, as every sentence involves decisions, some less obvious than others.

- Read your paper aloud slowly. Whether alone or with someone, ensure your words make sense when spoken. Rewrite confusing sentences for clarity.

- Explain your argument orally. Set the paper aside and concisely describe your argument. If your listener understands easily, ensure your written words match that clarity. If they need clarification, revise your terms. Practicing this with a peer can sharpen your articulation skills.

- Seek feedback from an outsider. Have someone unfamiliar with the topic read your paper and highlight confusing words or sentences. Don’t dismiss their confusion as ignorance; revise for clarity.

- Review additional resources. Explore our handouts on style, passive voice, and proofreading for further guidance.

|

43 videos|132 docs|32 tests

|

FAQs on Word Choice and Usage Chapter Notes - Language Arts for Grade 12

| 1. What are some common examples of awkward word choices that should be avoided in writing? |  |

| 2. How can wordiness affect the clarity of academic writing? |  |

| 3. What strategies can be used to eliminate clichés from academic writing? |  |

| 4. Why is it important to select key terms carefully when writing for an academic audience? |  |

| 5. What questions should writers ask themselves to ensure effective word choice? |  |