Reducing Reagents (Part-2) | Organic Chemistry PDF Download

Dissolving Metal Based Reduction (Birch Reduction)

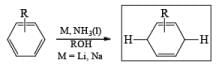

The 1, 4-reduction of aromatic rings to the corresponding unconjugated cyclohexadienes and heterocycles by alkali metals (Li, Na, K) dissolved in liquid ammonia in the presence of an alcohol is called the Birch reduction.

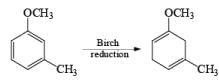

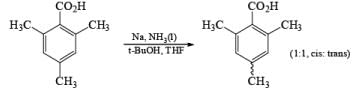

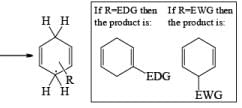

Heterocyclic, such as pyridines, pyrroles, and furans, are also reduced under these conditions. When the aromatic compound is substituted, the regioselectivity of the reduction depends on the nature of the substituent. If the substituent is electron-donating, the rate of the reduction is lower compared to the unsubstituted compound and the substituent is found on the non-reduced portion of the new product. In the case of electron-withdrawing substituents, the result is the opposite. Ordinary alkenes are not affected by the Birch reduction conditions, and double bonds may be present in the molecule if they are not conjugated with an aromatic ring.

The functional groups which are reduced by Birch reduction: (1) Aromatic compounds (2) α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds (3) Carbonyl compounds. (4) Internal alkynes (5) Conjugated alkenes.

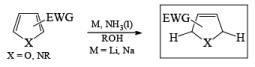

Limitations to the Birch reduction: Electron-rich heterocycles need to have at least one electronwithdrawing substituent, so furans and thiophenes are not reduced unless electron-withdrawing substituents are present.

1. Reduction of Aromatic Compounds with Metal and Ammonia:

Reaction Conditions: A typical procedure for the reduction of aromatic compounds: sodium metal (or Li wire) is cut into small pieces and slowly added to a solution of the aromatic substrate in a solvent mixture of liquid NH3, Et2O (or THF), and EtOH (or t-BuOH). The alcohol does not react with the metal at –33oC (bp of liquid ammonia).

Relative rates of benzene reduction are Li=360, Na=2, and K= 1.

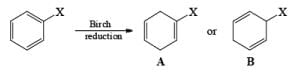

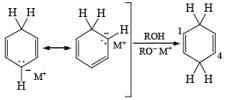

Regiochemistry: Birch reduction of monosubstituted benzenes could furnish either of two possible 1, 4-cyclohexadienes, A or B below

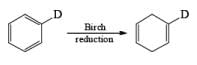

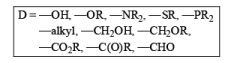

The regiochemical course of the reduction of substituted benzenes is determined by the site of initial protonation of the radical anion species. Generally, electron-donating groups (D) retard electron transfer and remain on unsaturated carbons.

The reason why groups such as –COR, –CHO, and –COR behave as electron-donating groups in this reaction is that they are reduced to –CH2O– before reduction of the aromatic system occurs.

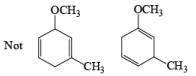

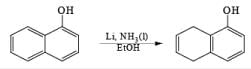

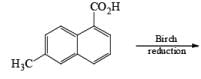

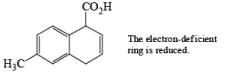

The deactivating effects of alkyl and alkoxy substituents on the regiochemistry of reduction of substituted naphthalenes are exemplified below.

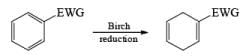

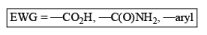

Electron-withdrawing groups (EWG) facilitate electron transfer and reside on saturated carbons. As with all Birch reductions, the saturated (sp carbons are para to each another

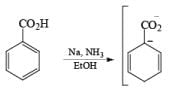

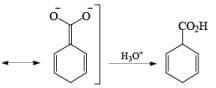

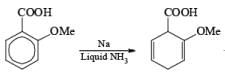

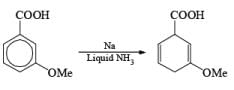

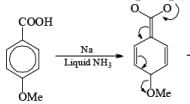

Reduction of benzoic acid and ortho / meta/ and para -methoxy benzoic acid:

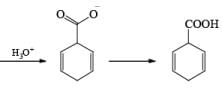

Birch reduction of benzoic acids in the presence of an alcohol (proton donor) furnishes 1, 4-dihydrobenzoic acids.

The carboxylate salt (–COOM) formed during reduction of benzoic acid derivatives is sufficiently electron rich that it is not reduced

The carboxy group generally dominates the regiochemistry of the reduction when other substituents are present

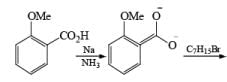

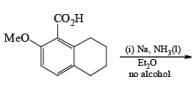

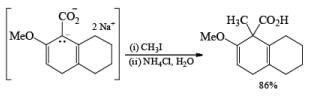

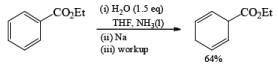

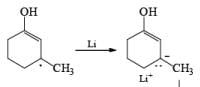

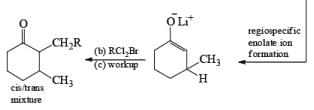

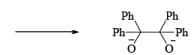

The strong activation effect by the carboxyl group allows reduction to occur when only one equivalent of alcohol is present or even without an alcohol. In these cases, the intermediate dianion persists in solution and can be trapped with electrophilic reagents to generate a quaternary carbon center

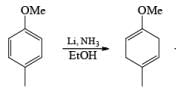

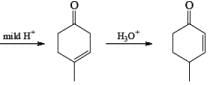

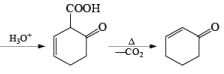

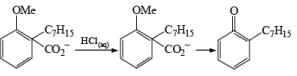

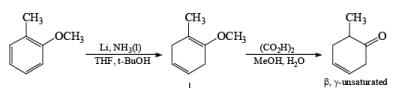

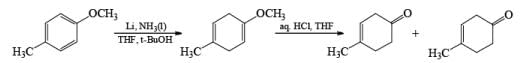

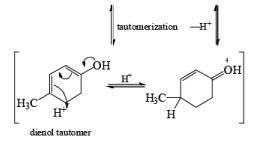

Formation of Cyclohexenones: Hydrolysis of the initial enol ether (vinyl ether) formed from Birch reduction of anisole or substituted anisoles under mild acidic conditions leads to β, γ-unsaturated cyclohexenones. Under more drastic acidic conditions, these isomerize to the conjugated α, β-cyclohexenones. Birch reduction of anisoles followed by hydrolytic workup is one of the best methods available for preparing substituted cyclohexenones.

It should be noted that Birch reduction of 4-substituted anisoles followed by acidic workup (aq HCl, THF) produces mixtures of isomeric cyclohexenones containing an appreciable amount of the β, γ-unsaturated product.

While ester groups are reduced competitively with the aromatic ring under the usual Birch conditions, addition of one or two equivalents of H2O or t-BuOH to NH2 before metal addition preserves the ester moiety.

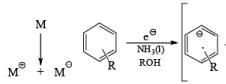

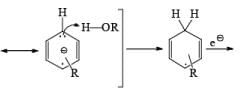

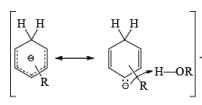

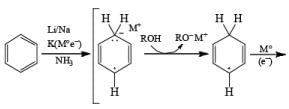

Mechanism for the Reduction of Aromatic Compounds

Birch reduction of substrates containing inethoxy or N, N-dimethylamino groups may be contaminated with appreciable amounts of conjugated products. In these cases, it is conceivable that the isomerization occurs during orkup. Allylic and benzylic heteroatom substituents such as –OR, –SR, and halogens undergo concomitant hydrogenolysis during Birch reduction. However, benzylic –OH groups are converted to alkoxides, and the resultant electron-rich –CH2O– moiety resists further reduction.

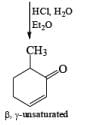

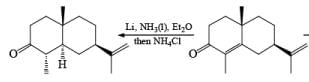

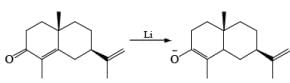

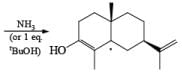

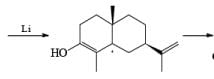

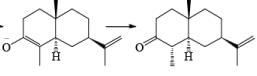

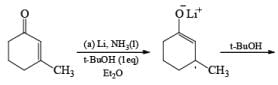

2. Reduction of α, β-unsaturated ketones

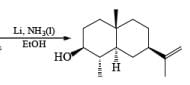

Reduction of α, β-unsaturated ketones gives the saturated ketone or saturated alcohol, depending on the conditions. Thus, α, -unsaturated ketones is converted to the ketone with lithium in ammonia. Reduction of α, β-unsaturated ketones with lithium in ammonia in the presence of proton source, gave the saturated alcohol.

Hydrogenation reduces both double bonds.

Mechanism

Reductions of α, β-unsaturated ketones with solutions of Li, Na, or K in liquid NH3 are chemoselective, resulting in the exclusive reduction of the carbon-carbon double bonds. The reaction involves addition of the substrate dissolved in Et2O or THF to a well-stirred solution of the metal in liquid NH3. Addition of one equivalent of t-BuOH as a proton donor is beneficial for driving the reduction to completion. However, excess alcohol, especially of the more acidic EtOH, causes further reduction of the saturated ketone initially formed to the corresponding alcohol.

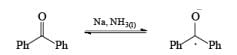

Reduction of carbonyl compounds

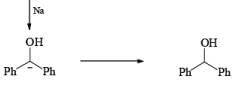

In these reactions an electron is transferred from the metal surface (or from the metal in solution) to the organic molecule giving, in the case of addition to a multiple bond, a radical anion, which in many cases is immediately protonated. The resulting radical subsequently takes up another electron from the metal to form an anion until workup. In the absence of a proton source, dimerization or polymerization of the radical anion may take place. In some cases a second electron may be added to the radical anion to form a dianion. In the reduction of benzophenone with sodium in ether or liquid ammonia, the ûrst product is the resonance-stabilized radical anion, which, in the absence of a proton donor, dimerizes to the pinacol. The presence in these radical anions of an unpaired electron that interacts with the atoms in the conjugated system has been established by measurements of the electron spin resonance spectra. Addition of organolithium species to benzophenone may also occur via the radical anion, as demonstrated by the deep blue colour generated in such reactions.

The metals commonly employed in these reductions include the alkali metals, calcium, zinc, magnesium, tin and iron.

The alkali metals are often used in solution in liquid ammonia or as suspensions in inert solvents such as ether or toluene, frequently with addition of an alcohol or water to act as a proton source. Many reductions are also effected by direct addition of sodium, or particularly, zinc or tin to a solution of the compound being reduced in a hydroxylic solvent, such as ethanol, acetic acid or an aqueous mineral acid.

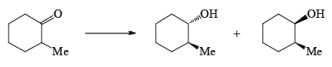

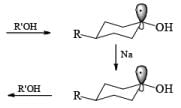

Reduction of ketones to secondary alcohols can be effected by catalytic transfer hydrogenation, by complex hydrides or by sodium and an alcohol. One feature of the sodium–alcohol method is that with cyclic ketones it normally gives rise exclusively or predominantly to the thermodynamically more stable alcohol. The ratios of the more-stable (trans) product (equatorial substituents) and the cis product, formed by reduction of 2-methylcyclohexanone.

The high proportion of the more-stable product (equatorial hydroxyl group) formed in the reduction with a metal– alcohol is thought to arise from the preference for the intermediate radical anion (or other intermediate) to adopt the configuration with the equatorial oxygen atom.

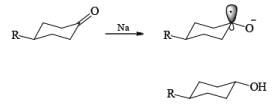

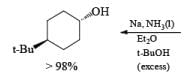

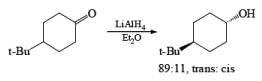

The ketone 4-tert-butylcyclohexanone similarly gives the more stable trans-4-tertbutylcyclohexanol almost exclusively on reduction with lithium and propanol in liquid ammonia.

In the case of cyclic ketones, the thermodynamically more stable alcohol predominates. For example, 4-tbutylcyclohexanone on reduction with Na in liquid NH3, Et2O and excess t-BuOH furnishes the trans-alcohol in greater than 98% isomeric purity, while reduction of the same ketone with LAH in ether provides the corresponding trans-alcohol in 89% isomeric purity.

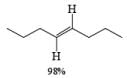

Reduction of internal alkynes to trans-alkene:

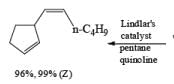

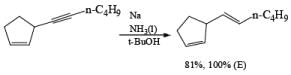

Lithium or sodium in liquid ammonia reduces disubstituted alkynes to trans-alkenes. The reaction is carried out by addition of the alkyne in ether to a mixture of Na in NH3(l), and the alkene produced is the (E)-isomer. Reduction and isomerization of the alkene are suppressed by addition of t-BuOH.

The reduction proceeds by addition of one electron from the metal to the triple bond to form a linear radical anion, which picks up a proton from the NH, solvent or from an added proton source, usually t-butanol, to give a vinyl radical. Subsequent transfer of another electron from the metal leads to the vinyl anion having the more stable transconfiguration. Protonation of the vinyl anion furnishes the trans-alkene

|

44 videos|102 docs|52 tests

|

FAQs on Reducing Reagents (Part-2) - Organic Chemistry

| 1. What are reducing reagents? |  |

| 2. What is the purpose of using reducing reagents? |  |

| 3. Can you provide examples of commonly used reducing reagents? |  |

| 4. What are the safety precautions to consider when working with reducing reagents? |  |

| 5. How do reducing reagents differ from oxidizing reagents? |  |