Deviation of Real Gases from Ideal Gas Behaviour | Chemistry for ACT PDF Download

A state of matter is one of the different forms. In everyday life, four states of matter are visible: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. Many intermediate states, such as liquid crystal, are known to exist, and certain states, such as Bose-Einstein condensates, neutron-degenerate matter, and quark-gluon plasma, are known to exist only under severe conditions, such as extreme cold, extreme density, and extreme energy. See the list of states of matter for a complete list of all exotic states of matter.

Behaviour of Real Gases

All of the gases are real-life instances. Although there is no such thing as an ideal gas, genuine gases are known to behave in ideal ways under certain circumstances. Nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, helium, and other actual gases are examples.

Ideal Gas and Real Gas: An ideal gas obeys the ideal gas equation PV=nRT at all pressures and temperatures. No gas, on the other hand, is excellent. Almost all gases vary in some manner from the ideal behaviour. Non-ideal or actual gases, such as H2, N2, and CO2, do not obey the ideal-gas equation.

Compressibility Factor

A new function called the Compressibility factor, denoted by Z, can be used to quantify the degree to which real gas deviates from ideal behaviour. It’s described as Z = PV/RT Plotting the compressibility factor, Z, vs. P, reveals the degree of departure from optimum behaviour. Temperature and pressure have no effect on an ideal gas, which has a Z value of 1. The value of Z is more or less than 1 determines the difference between ideal and real gas behaviour. The degree of gas nonideality is represented by the difference between unity and Z. Pressure and temperature cause deviations from optimal behaviour in a real gas. Using pressure and temperature to examine the compressibility curves of some of the gases discussed below.

Effect of Pressure Variation on Deviations

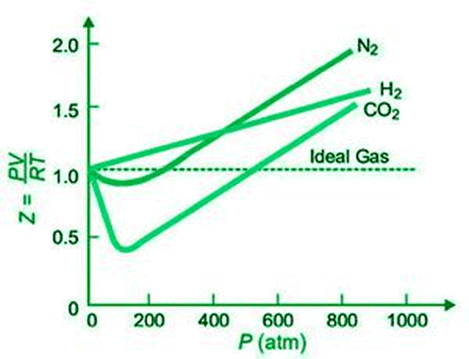

In the graph below, the compressibility factor, Z, for H2, N2, and CO2 at constant temperature is plotted against pressure.

For all of these gases, Z is practically equal to one at very low pressure. Real gases behave almost perfectly at low pressures (up to 10 atm). As the pressure rises, H2 exhibits a steady increase in Z (from Z=1). As a result, the H2 curve is higher than the ideal gas curve at all pressures. For N2 and CO2, Z decreases at first (Z1), then reaches a minimum, and finally increases with increasing pressure (Z>1). Because CO2 is the most easily liquefied gas, it has the greatest drop in the curve.

Effect of Temperature on Deviations

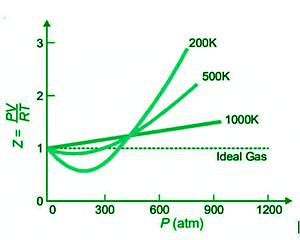

The graph below shows plots of Z or PV/RT against P for N2 at various temperatures.

As the temperature rises, the deviations from ideal gas behaviour become smaller and smaller, as shown by the shape of the graphs. At lower temperatures, the curve dips significantly, and the slope of the curve is negative. In this situation, Z<1. As the temperature rises, the dip in the curve decreases. The curve’s minimum vanishes at a certain temperature and remains horizontal for a wide range of pressures. At this temperature, PV/RT is nearly equal, thus Boyle’s law is satisfied. As a result, Boyle’s temperature refers to the temperature of the gas. Each gas has its own Boyle temperature, such as 332K for N2.

Note:

- Real gases perform approximately ideal at low pressures and relatively high temperatures, and the ideal-gas equation is obeyed.

- A real gas deviates greatly from ideality at low temperatures and sufficiently high pressures, and the ideal-gas equation is no longer valid.

- As the gas approaches the liquefaction point, the departure from ideal behaviour grows.

Van der Waals Equation (Causes of Real Gas Behaviour)

According to Van der Waals (1873), the deviations of real gases from ideal behaviour are attributable to two faulty kinetic theory postulates. The following are some of them:

- A gas’s molecules have no volume and have point masses.

- There are no intermolecular attractions in a gas.

As a result, the ideal gas equation PV=nRT developed from kinetic theory could not be applied to real gases. Van der Waals pointed out that the pressure (P) and volume (V) parts of the ideal gas equation needed to be modified to make it applicable to real gases.

Volume Correction

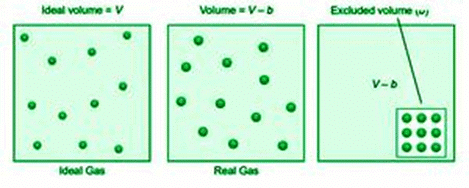

The volume of a gas is the amount of free space in the container where molecules can move about. The volume V of an ideal gas is equal to the volume of the container. Because ideal gas molecules have no volume, they can freely move around inside the container. In contrast, Van der Waals thought of molecules in a genuine gas as rigid spherical objects with a fixed volume.

As a result, the volume of a real gas is ideal volume minus gas molecule volume. If b is the effective volume of molecules per mole of gas, the volume of the ideal gas equation is rectified as follows: It becomes, (V–b) for n moles of gas.

(V–nb)

Where,

The excluded volume, abbreviated as b, is a constant and unique quantity for each gas.

Pressure Correction

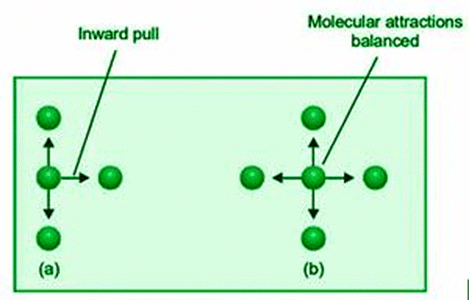

A molecule in the interior of gas is attracted by molecules on all sides. These appealing characteristics cancel each other out. A molecule poised to impact the vessel’s wall, on the other hand, is drawn only by molecules on one side. It feels forced to go inside as a result. As a result, it hits the wall with less force, and the real gas pressure, P, is less than the ideal pressure. If the actual pressure P is smaller than the ideal pressure Pideal by a factor p, we’ve got

P = Pideal – p

Pideal = P + p

Van der Waals determined the value of quantity p as follows:

p = an2/V2

Where n is the total number of gas molecules in volume V, and a denotes the gas’s proportionality constant. As a result, the ideal gas equation’s pressure P is revised to:

For n moles of gas, use (P+an2/V2).

When the adjusted pressure and volume numbers are substituted in the ideal gas equation, PV=nRT, we get:

(p+an2/V2) (V–nb) = nRT

For n moles of a gas, this is known as the Van der Waals equation or real gas equation. The Van der Waals equation becomes: for 1 mole of gas (n=1):

(p+a/V2)(V–b) = RT

|

110 videos|125 docs|115 tests

|