ICAI Notes- Unit 2: Theory of Consumer Behaviour | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Nature of Human Wants |

|

| Classification of Want |

|

| Relationship Between TU & MU |

|

| Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility |

|

| Consumer Surplus |

|

| Indifference Curve Analysis |

|

| Summary |

|

Nature of Human Wants

In economics, the term ‘want’ refers to a wish, desire or motive to own or/and use goods and services that give satisfaction. Wants may arise due to physical, psychological or social factors. Since the resources are limited, we need to make a choice between the urgent wants and the not so urgent wants.

- All wants of human beings exhibit some characteristic features.

- Wants are unlimited in number. All wants cannot be satisfied.

- Wants differ in intensity. Some are urgent, others are less intensely felt

- “Utility” depends on intensity of wants.

- In general, Utility is satisfaction. But in economic sense, Utility is a want satisfying power of a commodity.

- Each want is satiable

- Wants are competitive. They compete each other for satisfaction because resources are scarce in relation to wants

- Wants are complementary. Some wants can be satisfied only by using more than one good or group of goods

- A particular want may be satisfied in alternative ways

- Wants are subjective and relative. And hence, utility is also subjective or relative concept.

- Wants vary with time, place, and person and hence utility.

- Some wants recur again whereas others do not occur again and again Wants may become habits and customs

- Wants are affected by income, taste, fashion, advertisements and social norms and customs

- Wants arise from multiple causes such as physical and psychological instincts, social obligations and individual’s economic and social status

- Utility is a psychological concept. It is different from usefulness and has no concern with moral or ethical values.

- The two important concepts of utility are Total Utility (TU) and Marginal Utility (MU) which are useful in theories of consumer behaviour.

- TU refers to the sum total of utilities derived from the consumption of all the units of a commodity consumed by a consumer at a given time. In other words, it is a sum of marginal utilities up to the units consumed by a consumer. TU = ∑ MU

- MU is the additional utility derived from the consumption of an additional unit of the commodity. MU = TUn – TUn-1 Or MU = ∆TU /∆N

Classification of Want

In Economics, wants are classified into three categories, viz., necessaries, comforts and luxuries.

Necessaries

Necessaries are those which are essential for living. Necessaries are further sub-divided into necessaries for life or existence, necessaries for efficiency and conventional necessaries. Necessaries for life are things necessary to meet the minimum physiological needs for the maintenance of life such as minimum amount of food, clothing and shelter. Man requires something more than the necessities of life to maintain longevity, energy and efficiency of work, such as nourishing food, adequate clothing, clean water, comfortable dwelling, education, recreation etc. These are necessaries for efficiency. Conventional necessaries arise either due to pressure of habit or due to compelling social customs and conventions. They are not necessary either for existence or for efficiency.

Comforts

While necessaries make life possible comforts make life comfortable and satisfying. Comforts are less urgent than necessaries. Tasty and wholesome food, good house, clothes that suit different occasions, audio-visual and labour saving equipments etc .make life more comfortable.

Luxuries

Luxuries are those wants which are superfluous and expensive. They are not essential for living. Items such as expensive clothing, exclusive vintage cars, classy furniture and goods used for vanity etc. fall under this category.

The above categorization is not rigid as a thing which is a comfort or luxury for one person or at one point of time may become a necessity for another person or at another point of time. As all of us are aware, the things which were considered luxuries in the past have become comforts and necessaries today.

Relationship Between TU & MU

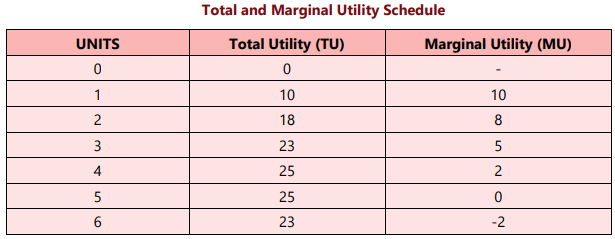

There is a unique relationship between TU and MU which can be explained with the help of below schedule and diagram.

- Both TU and MU are interrelated.

TU = ∑ MU & MU = TUn – TUn-1 - At first unit, TU = MU.

- Initially, when TU is increasing at decreasing rate, MU is decreasing but remains positive.

- When TU is maximum and constant, MU = 0 (zero).

- When TU starts decreasing, MU becomes negative.

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

The law of diminishing marginal utility is based on an important fact that while total wants of a person are virtually unlimited, each single want is satiable i.e. each want is capable of being satisfied.

Since each want is satiable, as a consumer consumes more and more units of a good, the intensity of his want for the good goes on decreasing and a point is reached where the consumer no longer wants it. In simple words it says that as a consumer takes more units of a good, the extra satisfaction that he derives from an extra unit of a good goes on falling.

It is to be noted that it is the marginal utility and not the total utility which declines with the increase in the consumption of a good.

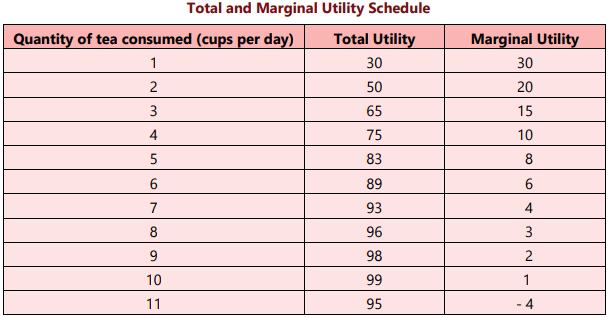

Let us illustrate the law with the help of an example. Consider table in which we have presented the total utility and marginal utility derived by a person from cups of tea consumed per day. When one cup of tea is taken per day, the total utility derived by the person is 30 utils (unit of utility) and marginal utility derived is also 30 utils with the consumption of 2nd cup per day the total utility rises to 50 but marginal utility falls to 20.

However, when the cups of tea consumed per day increases to 11, then instead of giving positive marginal utility, the eleventh cup gives negative marginal utility because it may cause him sickness.

The law of diminishing marginal utility is applicable only under certain assumptions:

(i) The different units consumed should be identical in all respects. The habit, taste, treatment and income of the consumer also remain unchanged.

(ii) The different units consumed should consist of standard units. If a thirsty man is given water by successive spoonful, the utility of second spoonful may conceivably be greater than the utility of the first.

(iii) There should be no time gap or interval between the consumption of one unit and another unit i.e. there should be continuous consumption.

(iv) The law may not apply to articles like gold, cash where a greater quantity may increase the lust for it.

(v) The shape of the utility curve may be affected by the presence or absence of articles which are substitutes or complements.

Consumer Surplus

The concept of consumer surplus was propounded by Alfred Marshall. Consumer surplus is a measure of welfare that people gain from consuming goods and services. It measures the benefits buyers receive from participating in a market. This concept occupies an important place not only in economic theory but also in economic policies of government and in decision-making of business firms.

The demand for a commodity depends on the utility of that commodity to a consumer. If a consumer gets more utility from a commodity, he would be willing to pay a higher price and vice-versa. The willingness to pay of each individual consumer based on his utility determines the demand curve. When price is less than or equal to the willingness to pay, the potential consumer purchases the good.

It is common knowledge that consumers generally are ready to pay more for certain goods than what they actually pay for them. This extra satisfaction which consumers get from their purchase of a good is referred to as consumer surplus by Alfred Marshall. Consumer surplus is defined as the difference between the total amount that consumers are willing and able to pay for a good or service (indicated by the demand curve) and the total amount that they actually do pay (i.e. the market price).

Marshall defined the concept of consumer surplus as the “excess of the price which a consumer would be willing to pay rather than go without a thing over that which he actually does pay”, is called consumers surplus.”

Thus, consumer surplus = what a consumer is ready to pay - what he actually pays.

The concept of consumer surplus is derived from the law of diminishing marginal utility. As we know, according to the law of diminishing marginal utility, the more of a thing we have, the lesser the marginal utility it has. In other words, as we purchase more of a good, its marginal utility goes on diminishing. The consumer is in equilibrium when the marginal utility of a good is equal to its price i.e., he purchases that many number of units of a good at which marginal utility is equal to price (It is assumed that perfect competition prevails in the market). Since the price is the same for all units of the good he purchases, he gets extra utility for all units consumed by him except for the one at the margin. This extra utility or extra surplus for the consumer is called consumer surplus.

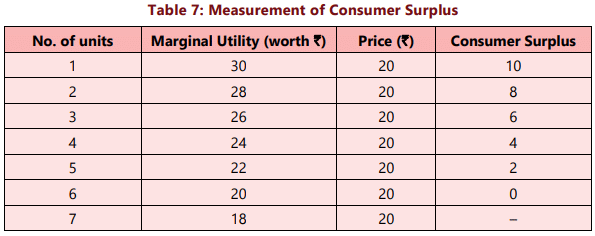

Consider Table 7 in which we have illustrated the measurement of consumer surplus in case of commodity X. There is only one price for a commodity in the market at a particular point of time. The price of X is assumed to be ₹ 20.

We see from the above table that when the consumer’s consumption increases from 1 to 2 units, his marginal utility falls from 30 to 28. His marginal utility goes on diminishing as he increases his consumption of good X. Since marginal utility for a unit of good indicates the price the consumer is willing to pay for that unit, and since market price is assumed to be at ₹20, the consumer enjoys a surplus on every unit of purchase till the 6th unit. Thus, when the consumer is purchasing 1 unit of X, the marginal utility is worth ₹30 and price fixed is ₹20, thus he is deriving a surplus of ₹ 10. Similarly, when he purchases 2 units of X, he enjoys a surplus of8 [28 – 20]. This continues and he enjoys consumer surplus equal to 6, 4, 2 respectively from 3rd, 4th and 5th unit. When he buys 6 units, he is in equilibrium because his marginal utility is equal to the market price or he is willing to pay a sum equal to the actual market price and therefore, he enjoys no surplus. Thus, given the price of ₹ 20 per unit, the total surplus which the consumer will get, is worth 10 + 8 + 6 + 4 + 2 + 0 = 30.

The concept of consumer surplus is closely related to the demand curve for a product. The demand curve reflects buyer’s willingness to pay; we can also use it to measure consumer surplus. As we know, the height of the demand curve measures the value buyers place on the good as measured by their willingness to pay for it. We have already seen above that the difference between the willingness to pay and the market price is each buyer’s consumer surplus. The difference between his willingness to pay and the price that he actually pays is the net gain to the consumer, the individual consumer surplus.

The total consumer surplus in a market which is the sum of all individual consumer surpluses in a market is equal to the area below the market demand curve but above the price. The term consumer surplus is often used to refer to both individual and total consumer surplus.

Thus, the total area below the demand curve and above the price is the sum of the consumer surplus of all buyers in the market.

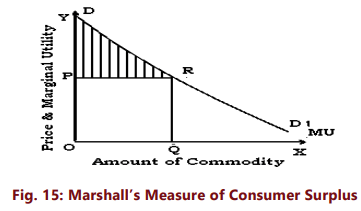

The concept of consumer surplus can be illustrated graphically. Consider figure 15. On the X-axis we measure the amount of the commodity and on the Y-axis the marginal utility and the price of the commodity. MU is the marginal utility curve which slopes downwards, indicating that as the consumer buys more units of the commodity, its marginal utility falls. Marginal utility shows the price which a person is willing to pay for the different units rather than go without them. If OP is the price that prevails in the market, then the consumer will be in equilibrium when he buys OQ units of the commodity, since at OQ units, marginal utility is equal to the given price OP. The last unit, i.e., Qth unit does not yield any consumer surplus because here price paid is equal to the marginal utility of the Qth unit. For all units before the Qth unit, the marginal utility is greater than price and thus these units fetch consumer surplus to the consumer.

In Figure 15, the total utility is equal to the area under the marginal utility curve up to point Q i.e. ODRQ. But, given the price equal to OP, the consumer actually pays OPRQ. The consumer derives extra utility equal to DPR which is nothing but consumer surplus. (The portion of demand curve RD1 is not relevant for our consumer as MUx is less than Px in this part and therefore, the consumer will not buy any quantity beyond Q.)

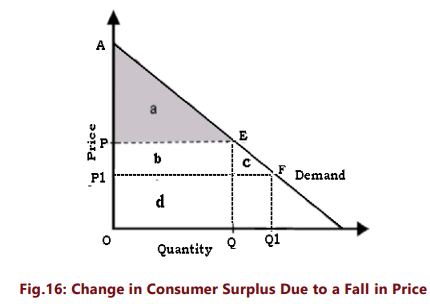

The consumer welfare derived from a good is the benefit a consumer gets from consuming that good minus what the consumer paid to buy the good. Consumer surplus is the buyer's net gain from purchasing a good. Graphically, it is the triangular area below the demand curve and above the price line. The size of the consumer surplus triangle depends on the price of the good. A rise in the price of a good reduces consumer surplus; a fall in the price increases consumer surplus. Thus, a higher price results in a smaller consumer surplus and a lower price generates a larger consumer surplus. The change in consumer surplus on account of a fall in price can be illustrated with the help of figure 16.

A fall in price from P to P1 increases consumer surplus from APE to A P1F.The increase in consumer surplus has two components.

(a) The increase in consumer surplus of existing buyers who were earlier paying price P (the rectangle marked b).

(b) The consumer surplus now available to the new buyers who started buying the commodity due to lower prices (the triangle c)

Applications

The concept of consumer surplus has important practical applications. Few such applications are listed below:

- Consumer surplus is a measure of the welfare that people gain from consuming goods and services. It is very important to a business firm to reflect on the amount of consumer surplus enjoyed by different segments of their customers because consumers who perceive large surplus are more likely to repeat their purchases.

- Understanding the nature and extent of surplus can help business managers make better decisions about setting prices. If a business can identify groups of consumers with different elasticity of demand within their market and the market segments which are willing and able to pay higher prices for the same products, then firms can profitably use price discrimination.

- Large scale investment decisions involve cost benefit analysis which takes into account the extent of consumer surplus which the projects may fetch.

- Knowledge of consumer surplus is also important when a firm considers raising its product prices Customers who enjoyed only a small amount of surplus may no longer be willing to buy products at higher prices. Firms making such decisions should expect to make fewer sales if they increase prices.

- Consumer surplus usually acts as a guide to finance ministers when they decide on the products on which taxes have to be imposed and the extent to which a commodity tax has to be raised. It is always desirable to impose taxes or increase the rates of taxes on commodities yielding high consumer surplus because the loss of welfare to citizens will be minimal.

Limitations

It is often argued that this concept of consumer surplus is hypothetical and illusory. In real life, the surplus satisfaction cannot be measured accurately.

- Consumer surplus cannot be measured precisely - because it is difficult to measure the marginal utilities of different units of a commodity consumed by a person.

- In the case of necessaries, the marginal utilities of the earlier units are infinitely large. In such case the consumer surplus is always infinite.

- The consumer surplus derived from a commodity is affected by the availability of substitutes.

- There is no simple rule for deriving the utility scale of articles which are used for their prestige value (e.g., diamonds).

- Consumer surplus cannot be measured in terms of money because the marginal utility of money changes as purchases are made and the consumer’s stock of money diminishes. (Marshall assumed that the marginal utility of money remains constant. But this assumption is unrealistic).

- The concept can be accepted only if it is assumed that utility can be measured in terms of money or otherwise. Many modern economists believe that this cannot be done.

Indifference Curve Analysis

In the last section, we have discussed the marginal utility analysis of demand. A very popular alternative and a more realistic method of explaining consumer demand is the ordinal utility approach. This approach uses a different tool namely indifference curve to analyse consumer behaviour and is based on consumer preferences. The approach is based on the belief that that human satisfaction, being a psychological phenomenon, cannot be measured quantitatively in monetary terms as was attempted in Marshall’s utility analysis. Therefore, it is scientifically more sound to order preferences than to measure them in terms of money. The consumer preference approach is, therefore, an ordinal concept based on ordering of preferences compared with Marshall’s approach of cardinality.

Assumptions Underlying Indifference Curve Approach

(i) The foundation of consumer behaviour theory is the assumption that the consumer knows his own tastes and preferences and possesses full information about all the relevant aspects of economic environment in which he lives.

(ii) The consumer is rational and tends to take rational actions that result in a more preferred consumption bundle over a less preferred bundle.

(ii) The indifference curve analysis assumes that utility is only ordinally expressible. The consumer is capable of ranking all conceivable combinations of goods according to the satisfaction they yield. Thus, if he is given various combinations say A, B, C, D and E, he can rank them as first preference, second preference and so on. However, if a consumer happens to prefer A to B, he cannot tell quantitatively how much he prefers A to B.

(iii) Consumer choices are assumed to be transitive. If the consumer prefers combination A to B, and B to C, then he must prefer combination A to C. In other words, he has a consistent consumption pattern.

(iv) If combination A has more commodities than combination B, then A must be preferred to B. This is sometimes referred to as the “more is better” assumption or the assumption of non-satiation.

Indifference Curves

The ordinal analysis of demand (here we will discuss the one given by Hicks and Allen) is based on indifference curve which represent the consumer’s preferences graphically. An indifference curve is a curve which represents all those combinations of two goods which give same satisfaction to the consumer. Since all the combinations on an indifference curve give equal satisfaction to the consumer, the consumer is completely indifferent among them. Or, it represents the set of all bundles of goods that a consumer views as being equally desirable. In other words, since all the combinations provide the same level of satisfaction the consumer prefers them equally and does not mind which combination he gets. An Indifference curve is also called iso-utility curve or equal utility curve.

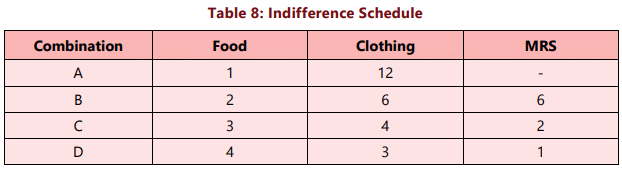

To understand indifference curves, let us consider the example of a consumer who has one unit of food and 12 units of clothing. Now, we ask the consumer how many units of clothing he is prepared to give up to get an additional unit of food, so that his level of satisfaction does not change. Suppose the consumer says that he is ready to give up 6 units of clothing to get an additional unit of food. We will have then two combinations of food and clothing giving equal satisfaction to the consumer: Combination A which has 1 unit of food and 12 units of clothing, and combination B which has 2 units of food and 6 units of clothing. Similarly, by asking the consumer further how much of clothing he will be prepared to forgo for successive increments in his stock of food so that his level of satisfaction remains unaltered, we get various combinations as given in table 8:

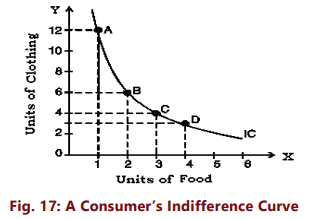

Now, if we plot the above schedule, we will get the following figure. In Figure 17, an indifference curve IC is drawn by plotting the various combinations given in the indifference schedule. The quantity of food is measured on the X axis and the quantity of clothing on the Y axis. As in indifference schedule, the combinations lying on an indifference curve will give the consumer the same level of satisfaction.

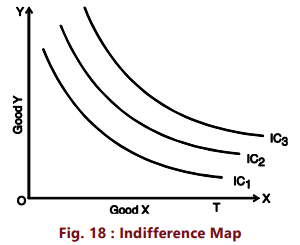

Indifference Curve Map

The entire utility function of an individual can be represented by an indifference curve map which is a collection of indifference curves in which each curve corresponds to a different level of satisfaction. In short, a set of indifference curves is called an indifference curve map. Each indifference curve is a set of points and each point shares a common level of utility with the others. Combinations of goods lying on indifference curves which are farther from the origin are preferred to those on indifference curves which are closer to the origin. Moving upward and to the right from one indifference curve to the next represents an increase in utility, and moving down and to the left represents a decrease. An indifference curve map thus depicts the complete picture of consumer tastes and preferences.

In Figure 18, an indifference curve map of a consumer is shown which consists of three indifference curves.

We have marked good X on X-axis and good Y on Y-axis. It should be noted that while the consumer is indifferent among the combinations lying on the same indifference curve, he certainly prefers the combinations on the higher indifference curve to the combinations lying on a lower indifference curve because a higher indifference curve signifies a higher level of satisfaction. Thus, while all combinations of IC1 give him the same satisfaction, all combinations lying on IC2 give him greater satisfaction than those lying on IC1.

Marginal Rate of Substitution

The Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS) is the rate at which a consumer is prepared to exchange goods X and Y, holding the level of satisfaction constant (i.e., moving along an indifference curve).

The marginal rate of substitution along any segment of an indifference curve refers to the maximum rate at which a consumer would willingly exchange units of Y for units of X. The MRS at any point on the indifference curve is equal to the (absolute value of) the slope of the curve at that point. When measured at a point, the MRSxy tells us the maximum rate at which a consumer would willingly trade good Y for a infinitesimal bit more of good X.

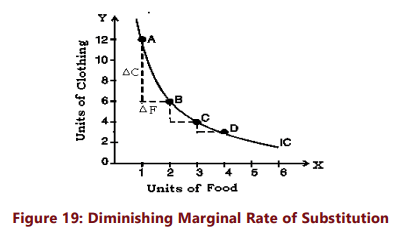

Consider Table-8. In the beginning the consumer is consuming 1 unit of food and 12 units of clothing. Subsequently, he gives up 6 units of clothing to get an extra unit of food, his level of satisfaction remaining the same. The MRS here is 6. Likewise when he moves from B to C and from C to D in his indifference schedule, the MRS are 2 and 1 respectively. Thus, we can define MRS of X for Y as the amount of Y whose loss can just be compensated by a unit gain of X in such a manner that the level of satisfaction remains the same.

We notice that MRS is falling i.e., as the consumer has more and more units of food, the trade –off or rate of substitution becomes smaller and smaller; i.e. he is prepared to give up less and less units of clothing.( Refer figure 19). When a consumer moves down his indifference curve, he gains utility from the consumption of additional units of good X, but loses an equal amount of utility due to reduced consumption of Y. But at each step, the utility levels from which the consumer begins is different. At point A in figure 19, the consumer consumes only a small quantity of food; and therefore his marginal utility of food at that point is high. At A, then, an additional unit of food adds a lot to his total utility. But at A he already consumes a large quantity of clothing; his marginal utility of clothing at that point is low. This means that it takes a large reduction in the quantity of clothing consumed to counterbalance the increased utility he gets from the extra unit of food.

On the contrary, consider point C. we find that the consumer consumes a much larger quantity of food and a much smaller quantity of clothing than at point A. This means that an additional unit of food adds only lesser utility, and a unit of clothing forgone costs more utility, than at point A. So the consumer is willing to give up less units of clothing in return for another unit of food at C(he gives up only 2 units of clothing for 1unit of food, whereas he gives up 6 units of clothing at point A for one unit of food).

Moving down the indifference curve—reducing consumption of clothing and increasing food consumption—will produce two opposing effects on the consumer’s total utility: reduction in total utility due to reduced consumption of clothing, and increase in total utility due to higher food consumption. In order to keep the levels of satisfaction constant, these two effects must exactly cancel out as the consumer moves down the indifference curve. The principle of diminishing marginal rate of substitution thus states that the more of good Y a person consumes in proportion to good X, the less Y he or she is willing to substitute for another unit of X.

There are two reasons for this.

- The want for a particular good is satiable so that when a consumer has more of it, his intensity of want for it decreases. Thus, in our example, when the consumer has more units of food, his intensity of desire for additional units of food decreases.

- Most goods are imperfect substitutes of one another. MRS would remain constant if they could substitute one another perfectly.

We know that along the indifference curve:

(Change in total utility due to lower clothing consumption) = (Change in total utility due to higher food consumption)

Change in total utility due to a change in clothing consumption = MU c × ΔQ c

Change in total utility due to a change in food consumption = MUf× ΔQf

Therefore, along the indifference curve:−MUc × ΔQc = MUf× ΔQf

Note that the left-hand side of the equation has a minus sign as it represents the loss in total utility from decreased clothing consumption. This must equal the gain in total utility from increased food consumption, represented by the right-hand side of the equation. Along the indifference curve:

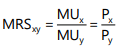

To generalize, the marginal rate of substitution of X for Y (MRSxy) is the slope of the indifference curve.

As the number of units of Y the consumer is willing to sacrifice gets lesser and lesser, the marginal rate of substitution gets smaller and smaller as we move down and to the right along an indifference curve. That is, the indifference curve becomes flatter (less sloped) as we move down and to the right.

Properties of Indifference Curves

The following are the main characteristics or properties of indifference curves:

(i) Indifference curves slope downward to the right: This property implies that the two commodities can be substituted for each other and when the amount of one good in the combination is increased, the amount of the other good is reduced. This is essential if the level of satisfaction is to remain the same on an indifference curve.

(ii) Indifference curves are always convex to the origin: It has been observed that as more and more of one commodity (X) is substituted for another (Y), the consumer is willing to part with less and less of the commodity being substituted (i.e. Y). This is called diminishing marginal rate of substitution. Thus, in our example of food and clothing, as a consumer has more and more units of food, he is prepared to forego less and less units of clothing. This happens mainly because of the want for a particular good is satiable and as a person has more and more of a good, his intensity of want for that good goes on diminishing. In other words, the subjective value attached to the additional quantity of a commodity decreases fast in relation to the other commodity whose total quantity is decreasing. This diminishing marginal rate of substitution gives convex shape to the indifference curves.

However, there are two extreme situations.

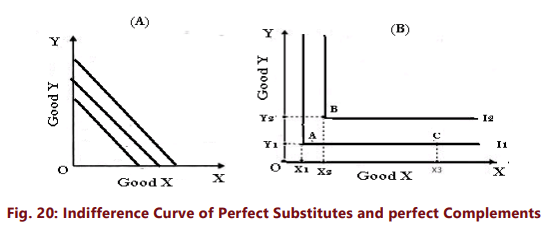

- When two goods are perfect substitutes of each other, the consumer is completely indifferent as to which to consume and is willing to exchange one unit of X for one unit of Y. His indifference curves for these two goods are therefore straight, parallel lines with a constant slope along the curve, or the indifference curve has a constant MRS.[Figure 20(A)].

- Goods are perfect complements when a consumer is interested in consuming these only in fixed proportions. When two goods are perfect complementary goods (e.g. left shoe and right shoe), the consumer consumes only bundles like A and B in figure 20(B) in which both X and Y in equal proportions. With a bundle like A or B, he will not substitute X for Y because an extra piece of the other good (here a single shoe) is worthless for him. The reason is that neither an additional left shoe nor a right shoe without a paired one of each, adds to his total utility. In such a case, the indifference curve will consist of two straight lines with a right angle bent which is convex to the origin, or in other words, it will be L shaped. [Figure 20(B)] Avery interesting fact about this is that in the case of perfect complements, the marginal rate of substitution is undefined because an individual’s preferences do not allow any substitution between goods.

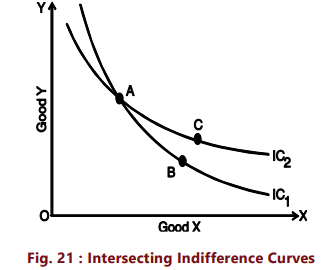

(iii) Indifference curves can never intersect each other: No two indifference curves will intersect each other although it is not necessary that they are parallel to each other. In case of intersection the relationship becomes logically absurd because it would show that higher and lower levels are equal, which is not possible. This property will be clear from Figure 21.

In figure 21, IC1 and IC2 intersect at A. Since A and B lie on IC1 , they give same satisfaction to the consumer. Similarly since A and C lie on IC2, they give same satisfaction to the consumer. This implies that combination B and C are equal in terms of satisfaction. But a glance will show that this is an absurd conclusion because certainly combination C is better than combination B because it contains more units of commodities X and Y. Thus we see that no two indifference curves can touch or cut each other.

(iv) A higher indifference curve represents a higher level of satisfaction than the lower indifference curve: This is because combinations lying on a higher indifference curve contain more of either one or both goods and more goods are preferred to less of them.

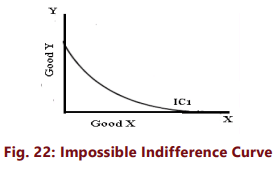

(v) Indifference curve will not touch either axes: Another characteristic feature of indifference curve is that it will not touch the X axis or Y axis. This is born out of our assumption that the consumer is considering different combination of two commodities. If an indifference curve touches the Y axis at a point P as shown in the figure 22, it means that the consumer is satisfied with OP units of Y commodity and zero units of X commodity. This is contrary to our assumption that the consumer wants both commodities although in smaller or larger quantities. Therefore an indifference curve will not touch either the X axis or Y axis.

The Budget Line

From the ordinal utility analysis discussed above, we have understood one part of a person’s consumption behavior namely, consumer preference. A higher indifference curve shows a higher level of satisfaction than a lower one. Therefore, a consumer, in his attempt to maximize satisfaction will try to reach the highest possible indifference curve. But in his pursuit of buying more and more goods and thus obtaining more and more satisfaction, he has to work under two constraints: first, he has to pay the prices for the goods and, second, he has a limited money income with which to purchase the goods.

Consumers maximize their well-being subject to constraints. The most important constraint all of us face in deciding what to consume is the budget constraint. In other words, consumers almost always have limited income, which constrains how much they can consume. A consumer’s choices are limited by the budget available to him. As we know, his total expenditure for goods and services can fall short of the budget constraint, but may not exceed it.

Algebraically, we can write the budget constraint for two goods X and Y as:

PXQX + PYQY ≤ B

Where

PX and PY are the prices of goods X and Y and QX and QY are the quantities of goods X and Y chosen and B is the total money available to the consumer.

The requirement illustrated by the equation above that a consumer must choose a consumption bundle that costs no more than his or her income is known as the consumer’s budget constraint. A consumer’s consumption possibilities are the set of all consumption bundles that can be consumed given the consumer’s income and prevailing prices. We assume that the consumer in our analysis uses up his entire nominal money income to purchase the commodities. So that his budget constraint is PXQX + PYQY = B

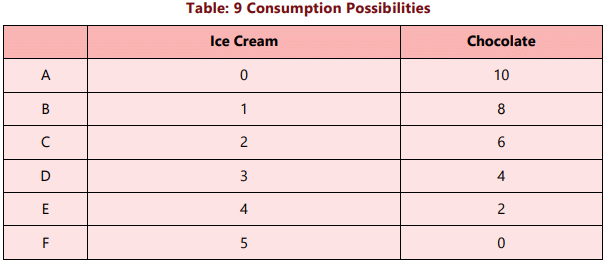

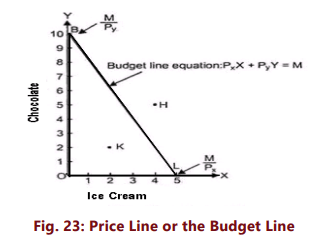

The following table shows the combinations of Ice cream and chocolates a consumer can buy spending the entire fixed money income of ₹100, with the prices ₹ 20 and ₹10 respectively.

The budget constraint can be explained by the budget line or price line. In simple words, a budget line shows all those combinations of two goods which the consumer can buy spending his given money income on the two goods at their given prices. All those combinations which are within the reach of the consumer (assuming that he spends all his money income) will lie on the budget line. The consumer could, of course, buy any bundle that cost less than ₹ 100.(e.g. Point K)

It should be noted that any point outside the given price line, say H, will be beyond the reach of the consumer and any combination lying within the line, say K, shows under spending by the consumer. The slope of the budget line is determined by the relative prices of the two goods. It is equal to ‘Price Ratio’ of two goods i.e. PX /PY i.e. It measures the rate at which the consumer can trade one good for the other. The budget line will shift when there is:

- A change in the prices of one or both products with the nominal income of the buyer (budget) remaining the same.

- A change in the level of nominal income of the consumer with the relative prices of the two goods remaining the same.

- A change in both income and relative prices

Consumer Equilibrium

Having explained indifference curves and budget line, we are in a position to explain how a consumer reaches equilibrium position by choosing his optimal consumption bundle, given the constraints. A consumer is in equilibrium when he is deriving maximum possible satisfaction from the goods and therefore is in no position to rearrange his purchases of goods. We assume that:

(i) The consumer has a given indifference map which shows his scale of preferences for various combinations of two goods X and Y.

(ii) He has a fixed money income which he has to spend wholly on goods X and Y.

(iii) Prices of goods X and Y are given and are fixed.

(iv) All goods are homogeneous and divisible, and

(v) The consumer acts ‘rationally’ and maximizes his satisfaction.

To show which combination of two goods X and Y the consumer will buy to be in equilibrium we bring his indifference map and budget line together.

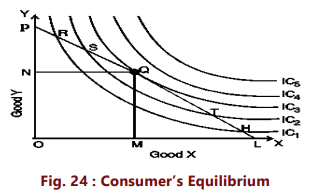

We know by now, that the indifference map depicts the consumer’s preference scale between various combinations of two goods and the budget line shows various combinations which he can afford to buy with his given money income and prices of the two goods. Consider Figure 24, in which IC1 , IC2 , IC3, IC4 and IC5 are shown together with budget line PL for good X and good Y. Every combination on the budget line PL costs the same. Thus combinations R, S, Q, T and H cost the same to the consumer. The consumer’s aim is to maximise his satisfaction and for this, he will try to reach the highest indifference curve.

Since there is a budget constraint, he will be forced to remain on the given budget line, that is he will have to choose combinations from among only those which lie on the given price line. Which combination will our hypothetical consumer choose? A consumer’s optimal choice should satisfy two criteria:

- It will be a point on his budget line; and

- It will lie on the highest indifference curve possible

The consumer can arrive this choice moving down his budget line starting from point R. While doing this, he will pass through a variety of indifference curves (To make the diagram simple, we have drawn only a few). Suppose he chooses R. We see that R lies on a lower indifference curve IC1, when he can very well afford S, Q or T lying on higher indifference curves. Similar is the case for other combinations on IC1 , like H. Again, suppose he chooses combination S (or T) lying on IC2. But here again we see that the consumer can still reach a higher level of satisfaction remaining within his budget constraints i.e., he can afford to have combination Q lying on IC3 because it lies on his budget line. Now, what if he chooses combination Q? We find that this is the best choice because this combination lies not only on his budget line but also puts him on the highest possible indifference curve i.e., IC3. The consumer can very well wish to reach IC4 or IC5, but these indifference curves are beyond his reach given his money income. Thus, the consumer will be at equilibrium at point Q on IC3. What do we notice at point Q? We notice that at this point, his budget line PL is tangent to the indifference curve IC3. In this equilibrium position (at Q), the consumer will buy OM of X and ON of Y. At the tangency point Q, the slopes of the price line PL and the indifference curve IC3 are equal. The slope of the indifference curve shows the marginal rate of substitution of X for Y (MRSxy) which is equal to  while the slope of the price line indicates the ratio between the prices of two goods i.e.

while the slope of the price line indicates the ratio between the prices of two goods i.e.

At equilibrium point Q,

Thus, we can say that the consumer is in equilibrium position when the price line is tangent to the indifference curve or when the marginal rate of substitution of goods X and Y is equal to the ratio between the prices of the two goods. We have seen that the consumer attains equilibrium at the point where the budget line is tangent to the indifference curve and

In fact the slope of the indifference curve points to the rate at which the consumer is willing to give up good Y for good X. The slope of the budget line tells us the rate at which the consumer is actually able to trade good X and good Y. When both these are equal, he will be maximizing his satisfaction given the constraints. The indifference curve analysis is superior to utility analysis: (i) it dispenses with the assumption of measurability of utility (ii) it studies more than one commodity at a time (iii) it does not assume constancy of marginal utility of money (iv) it segregates income effect from substitution effect.

Summary

- The existence of human wants is the basis for all economic activities in the society. All desires, tastes and motives of human beings are called wants in Economics.

- In Economics, wants are classified in to necessaries, comforts and luxuries. Utility refers to the want satisfying power of goods and services. It is not absolute but relative. It is a subjective concept and it depends upon the mental attitude of people.

- There are two important theories of utility, the cardinal utility analysis and ordinal utility analysis.

- The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as a consumer increases the consumption of a commodity, every successive unit of the commodity gives lesser and lesser satisfaction to the consumer.

- Consumer surplus is the difference between what a consumer is willing to pay for a commodity and what he actually pays for it.

- Consumer surplus is the buyer's net gain from purchasing a good. Graphically, it is the triangular area below the demand curve and above the price line.

- A rise in the price of a good reduces consumer surplus; a fall in the price increases consumer surplus

- The indifference curve theory, which is an ordinal theory, shows the household’s preference between alternative bundles of goods by means of indifference curves.

- Marginal rate of substitution is the rate at which the consumer is prepared to exchange goods X and Y.

- The important properties of an Indifference curve are: Indifference curve slopes downwards to the right, it is always convex to the origin, two ICs never intersect each other, it will never touch the axes and higher the indifference curve higher is the level of satisfaction.

- When two goods are perfect substitutes of each other, indifference curves for these two goods are straight, parallel lines with a constant slope along the curve, or the indifference curve has a constant MRS

- Goods are perfect complements when a consumer is interested in consuming only in fixed proportions. In such a case, the indifference curve will consist of two straight lines with a right angle bent which is convex to the origin, or in other words, it will be L shaped.

- Budget line or price line shows all those combinations of two goods which the consumer can buy spending his given money income on the two goods at their given prices.

- The slope of the budget line is determined by the relative prices of the two goods. It is equal to ‘Price Ratio’ of two goods. i.e. PX/PY i.e. It measures the rate at which the consumer can trade one good for the other.

- The budget line will shift when there is a change in the prices of one or both products with the nominal income of the buyer (budget) remaining the same or when there is a change in the level of nominal income of the consumer with the relative prices of the two goods remaining the same.

- A consumer is said to be in equilibrium when he is deriving maximum possible satisfaction from the goods and is in no position to rearrange his purchase of goods.

- The consumer attains equilibrium at the point where the budget line is tangent to the indifference curve and MUx / Px = MUy /Py = MUz /Pz

|

135 videos|190 docs|88 tests

|

|

135 videos|190 docs|88 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for CA Foundation exam

|

|