Additional Information about Incompatible Observables for Physics Preparation

Incompatible Observables Free PDF Download

The Incompatible Observables is an invaluable resource that delves deep into the core of the Physics exam.

These study notes are curated by experts and cover all the essential topics and concepts, making your preparation more efficient and effective.

With the help of these notes, you can grasp complex subjects quickly, revise important points easily,

and reinforce your understanding of key concepts. The study notes are presented in a concise and easy-to-understand manner,

allowing you to optimize your learning process. Whether you're looking for best-recommended books, sample papers, study material,

or toppers' notes, this PDF has got you covered. Download the Incompatible Observables now and kickstart your journey towards success in the Physics exam.

Importance of Incompatible Observables

The importance of Incompatible Observables cannot be overstated, especially for Physics aspirants.

This document holds the key to success in the Physics exam.

It offers a detailed understanding of the concept, providing invaluable insights into the topic.

By knowing the concepts well in advance, students can plan their preparation effectively.

Utilize this indispensable guide for a well-rounded preparation and achieve your desired results.

Incompatible Observables Notes

Incompatible Observables Notes offer in-depth insights into the specific topic to help you master it with ease.

This comprehensive document covers all aspects related to Incompatible Observables.

It includes detailed information about the exam syllabus, recommended books, and study materials for a well-rounded preparation.

Practice papers and question papers enable you to assess your progress effectively.

Additionally, the paper analysis provides valuable tips for tackling the exam strategically.

Access to Toppers' notes gives you an edge in understanding complex concepts.

Whether you're a beginner or aiming for advanced proficiency, Incompatible Observables Notes on EduRev are your ultimate resource for success.

Incompatible Observables Physics Questions

The "Incompatible Observables Physics Questions" guide is a valuable resource for all aspiring students preparing for the

Physics exam. It focuses on providing a wide range of practice questions to help students gauge

their understanding of the exam topics. These questions cover the entire syllabus, ensuring comprehensive preparation.

The guide includes previous years' question papers for students to familiarize themselves with the exam's format and difficulty level.

Additionally, it offers subject-specific question banks, allowing students to focus on weak areas and improve their performance.

Study Incompatible Observables on the App

Students of Physics can study Incompatible Observables alongwith tests & analysis from the EduRev app,

which will help them while preparing for their exam. Apart from the Incompatible Observables,

students can also utilize the EduRev App for other study materials such as previous year question papers, syllabus, important questions, etc.

The EduRev App will make your learning easier as you can access it from anywhere you want.

The content of Incompatible Observables is prepared as per the latest Physics syllabus.

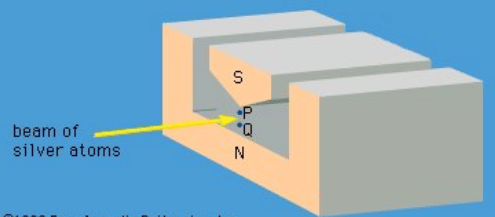

Figure 2: Magnet in Stern-Gerlach experiment. N and S are the north and south poles of a magnet. The knife-edge of S results in a much stronger magnetic field at the point P than at Q.

Figure 2: Magnet in Stern-Gerlach experiment. N and S are the north and south poles of a magnet. The knife-edge of S results in a much stronger magnetic field at the point P than at Q.