Key Notes: Theory of Consumer Behaviour | Economics for Grade 11 PDF Download

Consumer Behaviour

Consumer behaviour is the study of how customers or groups of customers choose, buy, use and dispose of ideas, goods, and services that meet their needs. It refers both to the actions of the consumer in the marketplace and the motivation behind those actions.

Utility

A commodity or a product can fulfil a specific need. The greater the utility of an item, either meeting a requirement or satiating a desire for it, the higher the demand. Utility is subjective. Different people may have different levels of utility for the same product. The utility (or satisfaction) that a consumer derives from an item will often determine his/her desire to purchase it.

Types of Utility

Under this section of Class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes, students learn about the types of Utility Analyses.

- Cardinal Utility Analysis: This analysis suggests that utility can be expressed numerically or that a product can be measured in terms of countable numbers. Suppose a person measures the utility derived from a shirt and says that the shirt gives 50 units of utility; then, we have two critical utility measures.

The two measures of utility are:

- Total Utility (TU), is the complete satisfaction derived from the consumption, at any given time, of a particular commodity. It is also known as the total marginal utility. Total utility depends on the quantity of the commodity consumed. Thus, it refers to the sum of the utilities derived from consuming n units of a commodity x.

TU = ∑MU or TU = MU1 + MU2 + MU3+ … + MUn - Marginal Utility (MU), is the change in total utility due to consumption of one additional unit of a commodity. It’s simply the value that each unit of a commodity adds to your overall utility.

MUn = TUn− TUn-1 - Ordinal Utility Analysis: This analysis explains that the satisfaction derived after consuming any goods or service cannot be quantified. These items can, however, be arranged in order of preference. The level of satisfaction derived from a product determines its utility. This definition is more realistic and more logical. An integral part of ordinal utility analysis is the inference curve. Sometimes ordinal utility analysis suffers from a major drawback in the form of quantification of utility in numbers. In real life though, one simply cannot express utility in the form of a number.

Relationship Between TU and MU

The relationship between TU and MU is defined and explained in-depth in our Class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes. Below are important points on it:

- As long as the MU remains positive, the TU will rise in proportion to increased commodity consumption.

- When MU starts decreasing from each succeeding unit, then TU grows or increases at a slower rate

- When the TU reaches its maximum value, the MU is reduced to zero. This is when TU stops expanding, also known as the point of safety. MU = 0 at point c , and TU is maximum at point a.

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

- It states that as a consumer consumes more units of a commodity, the marginal utility from each unit decreases.

- This principle is the basis of the law of demand. The concept of reduced pricing is also related to the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility.

- As a result, consumers prefer to pay less for more products if their utility is lower.

The assumptions for this law are as follows:

- Standard units are preferred in the commodity.

- The commodity is being continuously consumed.

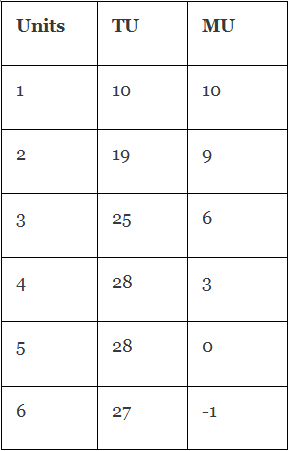

In the table, we can see that,

- MU continues to fall, while TU keeps increasing at a decreasing rate.

- When TU is maximum, which is 28 at the 5th unit, MU becomes 0.

- After that point, MU turns negative, and TU begins falling.

- TU will only increase if MU is positive. Once MU becomes negative, TU begins to fall.

Indifference Curve

In this section of our Class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes, students will learn about the indifference curve. Below we have covered a few major points from this section.

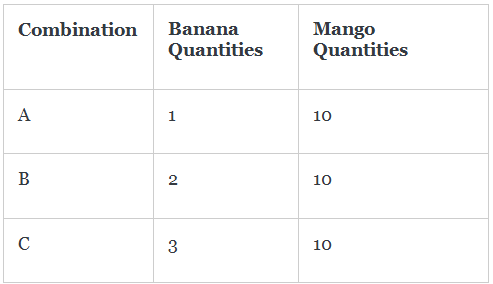

Refer below image and table for better understanding.

- An indifference curve is a graphic representation of all product combinations that provide the same level of satisfaction for the consumer.

- The indifference curve was created to show all the product combinations that offer the same level of satisfaction to the consumer, meaning that the consumer favours all these combinations equally.

- The standard indifference curve analysis is given with a simple, two-dimensional graph.

- Each axis represents two different forms of economic goods. As you see from the graph, the combinations of products on the indifference curve deliver the same level of utility to the consumer. So the customer along the indifference curve is not concerned with any of the combinations of products indicated by the points on the curve.

The Indifference Curve’s Characteristics

The characteristics of indifference curves are as follows:

- Downward slope: Indifference curves have a downward slope from left to right.

- Diminishing marginal rate of substitution (MRS): When the marginal utility of a dedicated commodity is positive, then an individual (customer) will always prefer more of that commodity. Hence, there will be an increase in the level of satisfaction and the marginal rate for substitution decreases.

- Indifference Curves never intersect: The curves of indifference don’t meet or intersect. It is impossible to provide the same level of satisfaction from two points on different Indifference Curves. If two indifference curves intersect each other, it will lead to conflicting results.

- Higher Indifference Curve: A higher indifference curve indicates a greater level of satisfaction.

- Indifference Curves never touch the y-axis or x-axis: An indifference curve does not touch any axis. If it touches any of the x or y axis, it means that the consumption on the other good is nil. And this is not possible as the indifference curve focuses on consumption of both the goods.

Consumers Budget

- A budget limit restricts the number of products and services a consumer can buy based on current prices and income.

- “Consumer budget” is the term used to describe a consumer’s purchasing power, with which they can buy quantitative bundles of 2 items at a fixed price. This means that the consumer cannot purchase goods in combinations (bundles) that cost less or equal to his income.

- In other words a consumer budget is the number of goods and services (including durable and non-durable goods) that can be bought by a consumer at a given time, given his income and the prices.

- Under the classical theory of consumer behaviour, the “budget line” derives from combining two goods that a person can purchase with a given amount of money.

- The consumer can be thought of as being on a budget line instead of having an income.

Budget Setting

A budget set is a collection of bundles that a consumer can buy using his current income and at the current market prices.

- A consumer’s budget is the sum of all bundles they can buy at current market prices.

- The consumer’s budget is a set of all the goods and services purchased with their available funds.

Budget Line:

The budget line shows all bundles equal in price to the consumer’s income. Based on a consumer’s revenue and commodity price, the budget line shows two possible combinations of goods that they can purchase.

Px Qx + Py Qy = S

Here,

Px = Commodity X price

Qx = Commodity X quantity

Py = Price of commodity Y

Qy = Commodity Y price

S = Income of Consumer

Attainable and Unattainable Combinations

Considering the consumer’s income and the price of goods, any point within the budget line is an affordable combination that the consumer can buy. The consumer can’t afford to purchase any goods beyond this area.

Budget Constraint

Budget constraint is defined as the sum of all combinations of products or goods that a person can afford based on their cost and income.

Changes or Shifts in Budget Line

The changes in the budget line include:

- A parallel shift may occur due to changes in income or the price of goods.

- Increased consumer income shifts budget lines to the right and vice versa.

- If the price of one item changes, there will be a rotation within the budget line. Prices fall and purchasing power increases, which causes outward rotation.

Derivation of the Slope of the Budget Line:

Under this section of Class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes we will learn about the derivation of the slope of the budget line.

The slope of budget line indicates the per unit change that is required in good 2 as per the unit change occurring in good 1 along the budget line

Let’s now calculate the slope for the budget line:

Take two points from the budget line.

E.g. (x1, x2) and (x1 + △x1 , x2 + △x2)

p1 x1 + p2 x2 = M ……. (1)

p1 (x1 + △x1) + p2 (x2 + △x2) = M ……. (2)

By subtracting (1) from (2), we will get

p1 △x1 + p2 △x2 = 0

By rearranging terms, we will get

△x2 △x1 = – p1 p2

Changes in Budget Set:

- The prices of the commodities and earnings determine the bundles available.

- When the price of one of the commodities or customer’s earnings changes, the set of available bundles is likely to change

Let’s say that the consumer’s earnings go up from M to M’, but the prices for the two goods remain the same. With the consumer’s new income, they can afford to buy all bundles (x1, x2 ) such that

p1x1 + p2x2 ≤ M′

Now the budget line equation will be given as:

p1x1 + p2x2 = M′

Optimal Choice of the Consumer

The budget set of the bundles is always available for the consumer. Here, the consumer has the freedom to consume any bundle from the budget set. It is assumed that consumers can choose their consumption bundle based on their tastes and preference. The equality of the marginal rate of substitution and the ratio of prices of the optimum bundle is the point where the budget line is tangent to the indifference curve.

- You can use the indifference curve or the budget line to show how consumers choose between two goods.

- The indifference curve represents the satisfaction curve.

- A consumer wants to get the best out of both goods if he has a limited budget. Therefore, he will strive to reach the highest indifference curve while remaining within his financial limits.

Demand

Demand can be defined as a consumer’s ability and willingness to buy a certain quantity of a product at a particular price and in a given period. The amount or quantity of a good that the customer chooses optimally eventually depends on the prices of other goods. Here, the consumer’s income and their tastes and preferences will change.

The demand function is the relationship between a commodity’s quantity and various determinants.

Dx = f ( Px , Pr , Y, T, E )

Dx= Quantity Demanded

f = Functional Relationship

Px = Original price of a good

Pr = Related price of a good

Y = Income

T = Tastes and Preferences of consumer

E = Expectations of consumer

Factors affecting Demand:

The factors affecting demand are:

- Product price: The commodity’s price has an inverted (negative) relationship to the quantity that commodity buyers are willing and capable of buying. Consumers will prefer to purchase lower-priced goods or services over higher-priced ones. The Law of Demand is a law that shows the inverse relationship between price and how much money people are willing to spend.

- Consumer’s Income: How much a buyer is willing to pay depends on what kind of product we are talking about.

- Normal Goods: There is a direct positive relationship between the income of a consumer and the amount of spending capacity they have. These merchandises have a simple formula: interest of consumers in the good will rise if income increases. If income decreases, interest will fall for that specific good. These are called normal goods.

- Inferior goods: However, a change in income has the opposite effect on other commodities. Inferior goods have lower demand as the wealth of the consumer increases. This means that customers’ need for inferior goods is inversely proportional to their income. In economics, the term inferior implies an inverted association between income and interest or demand for a commodity.

- As given in our Class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes, the quality of goods may also vary from one person to another. A commodity may be classified as normal goods for you, but it could be an inferior goods for someone else.

- Price of Related Goods: If the commodity price remains constant, there are two categories of interlinked goods that impact the demand for the good / commodity.

- Complementary Goods: These products can be consumed in combinations because they are less valuable if used separately. If one product is in high demand, the demand for the other will rise, even though its price remains the same.

- Substitute Goods: These are commodities that are diametrically opposite to each other. If one product is in high demand, the demand for the other products will fall, even though its price remains constant.

- Consumer preferences and tastes: When consumers start liking or preferring a particular product, then the demand for that product increases. Conversely, if there is a decrease in consumer preferences and tastes, the same product’s demand will decrease.

- Expectation: A consumer’s expectation of the future availability of a product will cause the product’s current demand to rise, and vice versa. This would keep the price constant.

Derivation of Demand Curve:

- The indifference curve analysis shows that a buyer maximises utility by choosing a package that includes two commodities and is within their budget. This information will be used for calculating a commodity’s demand curve.

- Consider an individual consuming bananas (X1) and mangoes (X2), whose income is M and market prices of X1 and X2 are P’1 and P’2 respectively. The figure depicts her consumption equilibrium at point C, where she buys X’1 and X’2 quantities of bananas and mangoes respectively. In panel (b) of the above figure, we plot P’1 against X’1 which is the first point on the demand curve for X1.

- Suppose the price of X1 drops to P1 with P2 and M remaining constant. The budget set in panel (a), expands and new consumption equilibrium is on a higher indifference curve at point D, where she buys more bananas ( X1 > X’1). Thus, demand for bananas increases as its price drops. We plot P1 against X1 in panel (b) of above figure to get the second point on the demand curve for X1.

- Likewise the price of bananas can be dropped further to P1, resulting in further increase in consumption of bananas to X1. P1 plotted against X1 gives us the third point on the demand curve. Therefore, we observe that a drop in the price of bananas results in an increase in the quality of bananas purchased by an individual who maximises their utility. The demand curve for bananas is thus negatively sloped.

- The negative slope of the demand curve can also be explained in terms of the two effects namely, substitution effect and income effect that come into play when the price of a commodity changes. When bananas become cheaper, the consumer maximises their utility by substituting bananas for mangoes in order to derive the same level of satisfaction from a price change, resulting in an increase in demand for bananas.

Law of Demand:

The law of demand describes the effects of price change on the item’s value.

According to it, if a commodity’s price falls, the amount of the item required will rise. Conversely, if a commodity’s price increases, the quantity of the product requested will decrease. The price of an object is related to its amount if all else is constant.

The exception to the Law of Demand:

- Sometimes, when the price goes up, so does the demand for it (and vice versa). These are the exceptions:

- Articles of distinction: These goods are given the highest status. The price of these goods must rise to preserve their prestige value. For example, antique pieces, precious jewels, etc. These goods are in high demand due to their high price.

- Goods of Basic Necessity: The demand for goods of primary necessity rises regardless of the price since they are a requirement.

- Giffen Good: if the income effect is stronger than the substitution effect, the demand for the good would be positively related to its price. Such a good is called a Giffen good.

Types of Goods:

- Normal Goods: These are products that see a rise in demand in response to an increase in the consumer’s income.

- Inferior Goods: These goods have a lower demand as consumers’ incomes rise. In other words, the need for lower-quality goods decreases as consumers become more financially able.

- Giffen Goods are low-income non-luxury items. These contradict traditional economic and consumer demand theories. Giffen goods are more in demand when their prices rise, and vice versa.

- Substitute Goods: These goods can be used interchangeably up to a certain extent. Tea and coffee, for example, are examples of substitute goods.

- Complementary goods: These items are usually consumed together and complement each other—for example, petrol and car.

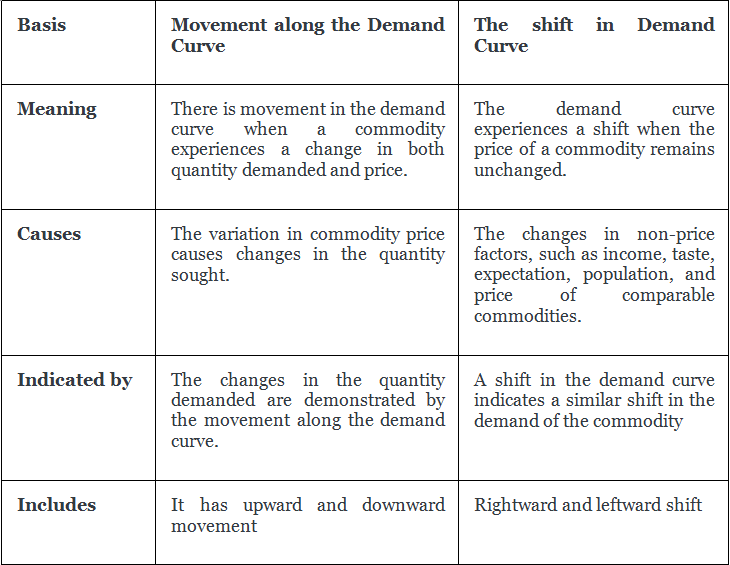

The shift in demand curve:

- A shift in the demand curve is a change in the potential price due to changes in other factors, such as income, taste, preferences, and consumer expectations.

- When the demand curve changes, the equilibrium point shifts.

- The demand curve shifts either in the right direction or left direction

- While the prices of goods and services do not change, other factors can cause a shift in consumer demand.

Movement along the Demand Curve:

- The demand curve’s movement indicates variation in price and quantity from one place to another.

- The demand curve changes when the amount of product or service is changed.

- You can see the movement along the demand curve in either an upward direction or downward direction

Difference – Movements along the Demand Curve and Shifts in the Demand Curve:

Market Demand

- The total quantity of an item sought in the market by all consumers at different prices at a given moment is known as market demand.

Elasticity of Demand

- The price elasticity of demand measures how a change in price affects the demand for a product among its consumers.

- It is calculated by dividing the percentage change in a product’s required quantity by the percentage change in its cost. This is also called the percentage method of elasticity of demand.

Ed = △Q△P×PQ

Here,

Ed = Elasticity of demand

△Q = Change in quantity

△P = Change in price

P = Initial price

Q = Initial Quantity

Situations of Elasticity of Demand:

- Ed= 1: Also called unitary elastic demand or rectangular hyperbola. When a change in demand and change in price is in the same proportion, i.e., a 10% increase in price leads to a 10% decrease in demand.

- Ed> 1: When a change in demand is greater than the price change. A 10% fall in price leads to a 30% increase in demand.

- Ed< 1: When a change in demand is less than the price change. A 30% decrease in price leads to a 10% increase in demand.

- Ed= 0: It is called perfectly inelastic demand, as here, irrespective of price change, demand remains constant.

Rectangular Hyperbola (Ed =1)

A rectangular hyperbola is a curve with equal rectangular areas on all sides. When the elasticity of demand equals one (Ed = 1) at all points along the demand curve, the demand curve is a rectangular hyperbola. As given in the figure below, it is a downward-sloping curve.

Geometric Method of Elasticity of Demand:

- The elasticity of demand is measured at any location by dividing the length of the lower segment of the demand curve by the size of the upper part of the demand curve at that point. At the midpoint of any linear demand curve, the value of Ed is unity.

- A linear demand curve’s elasticity may be assessed graphically. The elasticity of demand at each point on a straight-line demand curve is determined by the ratio between the demand curve’s lower and upper segments at that position.

Ed = DA/DB

Total Expenditure Method of Elasticity of demand:

- It will calculate the price elasticity of demand depending on the change in total expenditure (Price of Product and quantity) incurred by a household on the commodity due to a price change.

- The price of a particular commodity and its demand are inversely linked.

- Responsiveness of the commodity demand to its price changes determines whether expenditure on the product increases or decreases due to a rise in its price.

The Relationship between Total Expenditure and Price of Elasticity of Demand:

The relationship between total expenditure and price of elasticity of demand are as follows:

- Ed=1 When total spending (price X quantity) remains constant despite an increase or decrease in the original price of the good.

- Ed>1 When prices fall, total expenditure rises, and when prices rise, total spending falls.

- Ed<1 When total expenditure falls due to a price decrease, and incremental expenditure increases due to a price increase.

Factors that influence price elasticity of demand:

Let us now look at the essential elements that affect the price elasticity of demand:

- Nature of the Commodity: Demand for essential products such as food grains, medicines, etc. is less elastic since consumers will always consume these products in the quantity required, irrespective of its price. On the other hand, elasticity for comfort and luxuries like cars, ACs, etc. is more flexible because their consumption might be postponed if their costs rise.

- Price level: Demand for higher-priced commodities such as automobiles or air conditioners or LCD TVs is often more elastic than the demand for lower-priced products such as matchboxes or pencils.

- Income level: Higher-income groups have less elastic demand for commodities than lower-income groups. For example, if the price of an item rises, a wealthy consumer is unlikely to cut his demand, whereas a poor buyer may cut his demand.

- Availability of close substitute products: Demand for a commodity with many substitute products is usually more elastic than demand for products which have no substitutes. e.g. Pepsi, Coca-Cola, etc., and other similar beverages are suitable alternatives for each other. Even a minor increase in Pepsi price will attract purchasers to seek other available options. On the other hand, electricity or petrol demand will be less elastic because there are no substitutes.

Monotonic Preferences:

- Monotonic preference is built on the assumption that a normal consumer will always prefer “more” as compared to “less” of any given product. This means that a consumer is likely to be happier with bundles which would offer them more quantity of the same products.

Change in Budget Line:

- It is very much possible that there could be a shift parallel to the budget line. This could be to the left side or to the right side.

- This change typically happens due to a change in the product price or a change in the consumer’s income.

- The budget line typically shifts to the right side whenever there is a rise in consumer income and spending. If there is a decline in the income of the consumer, the budget line will shift towards the left side.

- Now suppose there are frequent changes in the cost of a product being sold, the budget line would rotate.

- The drop in price triggers outward radiation due to an increase in the purchasing power of money.

The subtopics covered under class 12 Microeconomics Chapter 2 notes include:

- The Consumer’s Budget: This subtopic will look at the basic concepts of budget set and budget line. The students will also study why there is a change in the budget line.

- Preferences of the Customer: In this sub-topic, we will examine why consumers choose their preferences for their consumption. These are Monotonic Preferences and Substitution between Goods etc.

- Demand Curve, the Law of Demand: In this Subtopic, we will gain information about the demand curve and illustrate it visually. The students will also learn the concepts of The Law of Demand.

- Market Demand: In this Sub-topic, we’ll learn how to determine the demand on the market for goods.

|

83 videos|367 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on Key Notes: Theory of Consumer Behaviour - Economics for Grade 11

| 1. What is the theory of consumer behavior? |  |

| 2. What are the key assumptions of the theory of consumer behavior? |  |

| 3. How does the theory of consumer behavior explain the concept of utility? |  |

| 4. What role does price play in the theory of consumer behavior? |  |

| 5. How does the theory of consumer behavior explain consumer demand? |  |